Abstract

Astaxanthin (AXT), a naturally occurring xanthophyll carotenoid with potent antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anticancer properties, has garnered significant attention as a multifunctional nutraceutical. However, its poor aqueous solubility, chemical instability, and low gastrointestinal bioavailability have limited its clinical and functional food applications. In recent years, food-grade nanoparticle systems, particularly lipid-based and polymeric nanocarriers, have emerged as promising platforms to enhance the oral bioavailability and targeted delivery of AXT. This review critically explores the latest advances in bioprocessing strategies for the formulation of AXT-loaded nanoparticles using food-safe materials, such as solid lipid nanoparticles, nanostructured lipid carriers, liposomes, protein-based carriers, and biodegradable polymers like chitosan and alginate. Key aspects, including preparation techniques, encapsulation efficiency, physicochemical stability, controlled release, and intestinal absorption mechanisms, are discussed. Furthermore, the review highlights the therapeutic efficacy of nanoparticle-mediated AXT delivery in addressing multiple health targets, such as oxidative stress, chronic inflammation, neurodegeneration, metabolic disorders, and cancer. Regulatory perspectives, safety considerations, and challenges related to industrial scalability are also addressed. Overall, this paper provides a comprehensive overview of food-grade nanocarriers as a transformative approach for the oral delivery of AXT, paving the way for its successful integration into functional foods.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A red, fat-soluble carotenoid known as Astaxanthin (AXT) belongs to the xanthophyll family and exhibits potent biological properties1,2. While AXT offers numerous health advantages, its applications in food and pharmaceutical sectors are restricted due to its poor water solubility and sensitivity to environmental factors such as oxygen, light, and elevated temperatures3,4. The natural stability of AXT can be enhanced through binding with proteins or fatty acids5. The effectiveness of oral AXT administration is hampered by its limited blood vessel distribution and cellular uptake. To address these challenges, researchers have focused on encapsulation techniques to enhance AXT’s bioavailability, stability, and solubility. This approach helps shield AXT from stomach acids while enabling controlled intestinal release. Various encapsulation methods have been employed for AXT formulation, including liposomes, spray drying, solvent evaporation, ionic gelation, coacervation, and lyophilization. However, these techniques face challenges in particle size control and product purification due to solvent usage. An eco-friendlier approach using supercritical fluid precipitation has emerged recently. One study achieved 84% encapsulation efficiency using supercritical carbon dioxide (SC-CO₂) with AXT emulsion, ethyl acetate-saturated water, and ethyl cellulose, while maintaining AXT’s antioxidant properties6. Another investigation reported 91.5% encapsulation efficiency using SC-CO₂ technology with poly(l-lactic acid), dichloromethane, and acetone7.

The efficacy of AXT encapsulation largely depends on capsule size and structure. Multilayered nanometric structures, such as liposomes and oil-in-water emulsions, offer superior stability, biological activity, and controlled release capabilities8. These micro/nanocapsules not only protect AXT during digestion but also enhance its bioavailability through endocytosis or Peyer’s patches absorption when sized below 500 nm9. The protective and bioavailability-enhancing properties of lipidic particles are influenced by their physicochemical characteristics, including size, charge, surface properties, and composition10. Compared to liposomes, nanostructured lipid carriers demonstrate better stability against digestive enzymes and stomach acid. Various materials can enhance carrier stability, such as phospholipids, saturated lipids, phytosterols, and surfactant-based systems like niosomes11. Materials like alginate/gelatin and whey protein/gum Arabic combinations provide pH-dependent protection, remaining stable in acidic conditions while releasing AXT in the intestinal environment6. Chitosan-based nanoparticles, despite their advantages in membrane affinity and biodegradability, require modification with compounds like casein and oxidized dextran to improve their acid resistance12. The selection of appropriate encapsulation systems depends on factors such as target organ characteristics, material availability, cost-effectiveness, and administration route13,14,15,16. Recent studies suggest that chitosan combined with proteins or carbohydrates, along with nanoniosomal and nanostructured lipid carriers, represents a promising delivery system for AXT. This review examines the characteristics and applications of AXT-encapsulated nanocarriers, discussing recent developments, limitations, and practical considerations for various therapeutic applications, including neurological, ocular, and dermal conditions.

AXT: Properties, benefits, and limitations in oral delivery

The chemical compound AXT, characterized by its molecular formula C₄₀H₅₂O₄ and molar mass of 596.84 g/mol, is naturally found in diverse marine organisms and living creatures, including salmon, shrimp, krill, lobster, various microorganisms, and certain plant species17. In contrast, synthetic AXT production involves a complex multi-step process using petrochemical materials. The chemical synthesis of AXT can be achieved through three distinct methods: canthaxanthin hydroxylation, zeaxanthin oxidation, or the Wittig reaction involving dialdehyde and two phosphoniums (Fig. 1). Currently, only naturally derived AXT has received approval for human consumption. While natural AXT serves as a premium ingredient in various therapeutic applications, synthetic AXT is primarily restricted to aquaculture use as a feed supplement18. Research has demonstrated that natural AXT possesses 20–50 times greater antioxidant capacity compared to its synthetic counterpart, displaying enhanced therapeutic efficacy without toxic effects19. The growing recognition of natural AXT’s superior properties has led to increased consumer demand and usage compared to synthetic versions. Primary sources of natural AXT include algae (particularly Haematococcus Pluvialis), bacterial species (Paracoccus haeundaensis and Paracoccus carotinifaciens), and yeast (Phaffia rhodozyma/Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous). Among these, Haematococcus pluvialis, a freshwater microalgae, stands out as a particularly rich source of natural AXT20,21. The pharmaceutical industry’s increasing interest in AXT has prompted numerous companies to focus on algae-based production22,23. However, the biotechnological production faces significant challenges in downstream processing. Since AXT is produced within cells and pharmaceutical applications require high-purity products, operational costs are substantial, with downstream processing accounting for approximately 80% of total production expenses22,24. Implementing efficient downstream processes could significantly reduce production costs and improve overall productivity. AXT exists in nature predominantly in its esterified form, though non-esterified variants are also present. Based on its two hydroxyl groups, AXT appears in three distinct forms: non-esterified (free form), mono-esterified (single hydroxyl group bonded to fatty acid), and di-esterified (both hydroxyl groups bonded to fatty acids). Different AXT sources produce varying ratios of these forms. For example, yeast-derived AXT from Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous yields the (3R, 3′R) isomer in free form, while Haematococcus pluvialis primarily produces the (3S, 3′S) isomer in mono-esterified form.

Key biochemical and chemical transformation pathways involved in the production of astaxanthin, an important xanthophyll carotenoid, from the precursor molecules canthaxanthin and zeaxanthin are illustrated here. The diagram outlines two primary routes leading to astaxanthin synthesis: one involves the conversion of canthaxanthin into astaxanthin, while the other proceeds via the transformation of zeaxanthin to astaxanthin. In the upper sequence, canthaxanthin, characterized by two terminal keto groups, is first hydroxylated to generate astaxanthin, which possesses both terminal keto and hydroxyl groups on each end ring. In the middle route, zeaxanthin, which contains two terminal hydroxyl groups, undergoes oxidation to produce astaxanthin with combined hydroxyl and keto groups on both cyclic ends. The final sequence at the bottom of the figure demonstrates a chemical synthesis approach where zeaxanthin is first modified via an oxidation reaction; here, reagents such as triphenylphosphine and bromide ion are indicated, along with a formyl group (aldehyde group) addition, resulting in the final astaxanthin molecule. All chemical structures are represented as skeletal formulas, with the locations of hydroxyl (OH), keto (carbonyl, C double bond O), and formyl (CHO) groups explicitly shown on the respective cyclic ends of the carotenoid backbone. Double arrows indicate the direction of enzymatic or synthetic conversion. Abbreviations and chemical symbols: OH: hydroxyl group; C=O: keto or carbonyl group; CHO: formyl (aldehyde) group; Triphenylphosphine and bromide ion: reagents used for the transformation.

The AXT molecule, containing multiple conjugated double bonds, can exist in two geometric configurations: Z and all-E isomers. In nature, the predominant and more stable form is the all-E isomer, where carbon atoms are positioned in E configurations at double bonds. The less stable but more beneficial Z isomers (comprising 9Z and 13Z variants) can form when AXT extracts are exposed to various factors, including metal ions25, solvents, heat, or pH variations in the reaction environment26. Research by Viazau and colleagues27 investigated AXT isomerization under heat and light conditions in both laboratory settings and living H. pluvialis cells. In vitro experiments with methanol showed an initial increase in Z-isomers to 5% during the first 5 hours of light exposure, followed by a decrease. Heat treatment, however, resulted in continuous accumulation of Z-isomers27. In H. pluvialis cells exposed to intense light and sodium acetate, Z-isomer levels initially peaked at 45% before declining, possibly due to new all-E-AXT synthesis and oxidative breakdown. Their findings suggest that while long-term light exposure with sodium acetate optimizes total AXT production in H. pluvialis cells, brief light exposure is sufficient for Z-isomer formation27. Multiple studies have highlighted the advantages of Z isomers over E isomers. Yang and colleagues observed preferential accumulation of 13Z-AXT in human plasma, suggesting enhanced health benefits of Z isomers28. The Z isomers’ superior solubility in organic solvents improves their extraction efficiency, particularly when using Z-isomerization catalysts26. The transformation from crystalline to amorphous state in Z configurations facilitates extraction, emulsification, and micronization processes using safe solvents29.

Z-isomerization also enhances various therapeutic properties, including anticancer, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antiaging, and antiatherosclerotic effects29. Yang’s research demonstrated superior anti-inflammatory properties of Z-isomers, particularly 9Z, through reduced expression of NK-κ, IL-8, TNF-α, and COX2 in Caco-2 cell models30. Antiaging studies showed that 9Z-AXT increased Caenorhabditis elegans’ median lifespan by 59.39%, compared to 30.43% with all-E-isomers31. These enhanced functionalities of AXT Z-isomers stem from altered physicochemical properties, including solubility, color value, stability, crystallinity, and melting point. Changes in Gibbs free energy affect Z-isomer stability, subsequently influencing its antioxidant capabilities32. Research by Liu and Osawa demonstrated that Z-isomers, particularly 9Z-AXT, exhibit powerful antioxidant effects through efficient radical scavenging and suppression of ROS production in neuroblastoma cells, while also inhibiting hydroperoxide formation33. Complementary studies by Yang and colleagues revealed that 13Z-AXT demonstrates superior antioxidant properties compared to both all-E and 9Z forms34. Z-isomers show enhanced solubility in organic solvents, vegetable oil, and SC- CO₂, leading to improved bioaccessibility and more effective uptake by bile acids and carotenoid transport proteins in Caco-2 cells. AXT exhibits both antioxidant and prooxidant properties, with low ROS levels playing beneficial roles in gene expression, cellular signaling, and antioxidative defense stimulation35. Studies indicate that AXT surpasses beta-carotene in neutralizing free radicals from both internal sources (inflammation, aging, stress, cancer) and external factors (cigarette smoke, pollutants, UV radiation)36,37.

AXT esters play a crucial role in mitigating lipid peroxidation due to their potent antioxidant properties. Astaxanthin and its esters are highly effective in protecting unsaturated fatty acid methyl esters from oxidative degradation. Research has demonstrated that AXT esters exhibit significant antilipid peroxidation activity at concentrations as low as 200 nM (ED₅₀), making them more than 100 times more potent than vitamin E analogs38. In terms of therapeutic dosing, both animal and human studies have provided compelling evidence of AXT esters’ efficacy. In animal models, administration of AXT esters at a dose of 250 µg/kg body weight resulted in the restoration of antioxidant enzyme levels and a reduction in lipid peroxidation by more than fivefold compared to toxin-exposed control groups39. Similarly, in human supplementation trials, high doses of astaxanthin (≥20 mg/day) were associated with significant antioxidant effects, including marked reductions in lipid peroxidation biomarkers such as malondialdehyde and isoprostane. In contrast, lower doses (<20 mg/day) did not yield statistically significant effects40. Despite its well-established antioxidant capacity, AXT like many antioxidants—may exhibit prooxidant behavior when administered at excessively high concentrations. However, the specific thresholds at which AXT esters shift from antioxidant to prooxidant activity remain less clearly defined in the scientific literature compared to other antioxidant compounds23,41.

Numerous studies have documented AXT’s health-promoting effects across various conditions. It enhances immune system function by boosting antibody production through T helper-dependent mechanisms, increasing antibody-secreting spleen cells and blood cell immunoglobulin production. Its potent antioxidant properties may benefit cardiovascular health42,43,44,45,46,47,48. Coombes et al. did not provide any possible explanation for the unusual efficacy of astaxanthin in kidney transplant patients. Their study found no significant effect, and the discussion did not address or speculate on any unexpected therapeutic benefit in this population49. Research suggests AXT significantly impacts cardiac function, joint strength, exercise performance, and recovery50. In heart failure patients, 3 months of AXT consumption improved exercise tolerance, cardiac contractility, and reduced oxidative stress51. Multiple studies confirm AXT’s antitumor properties, including anti-inflammatory52, antiproliferative53, antioxidant effects54, and enhanced apoptosis55. AXT demonstrates neuroprotective benefits, potentially reducing or preventing conditions like Parkinson’s, autism, and Alzheimer’s disease56,57. It also provides dermatological benefits, reducing wrinkles, preventing age spots, improving skin elasticity, and offering protection against UV damage58,59.

AXT exerts its effects by modulating pathways related to inflammation, oxidative stress, and apoptosis that depend on reactive oxygen species, especially in contexts of neurodegenerative processes and damage to ocular and skin tissues60,61. Although reactive oxygen species serve important functions in neuronal activity, their overproduction can lead to irreversible neural cell damage. The neuroprotective capabilities of AXT function through reducing ROS within cells and inhibiting the production of hydrogen peroxide in mitochondria62. Research demonstrates that AXT exhibits anti-inflammatory capabilities through its ability to suppress various inflammatory mediators, including interleukins, TNF-α, and ICAM1 (Fig. 2)60,63. Studies indicate that AXT’s anti-inflammatory effects stem from multiple mechanisms, particularly its ability to suppress the TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signaling cascade64. This pathway modulation is especially significant in controlling inflammation in burn-related kidney damage, where AXT reduces TLR4 and MyD88 expression65. In ocular tissues, AXT demonstrates anti-inflammatory properties by interfering with NF-kB signaling and reducing TNF-α, NO, and PGE2 production66. Furthermore, AXT reduces choroidal neovascularization by decreasing inflammatory markers such as ICAM-1, VEGF from macrophages, MCP-1, and IL-667.

The molecular mechanisms by which astaxanthin regulates cellular responses to inflammation, apoptosis, and oxidative stress are summarized in this figure. Astaxanthin acts through multiple signaling routes, linking antioxidant, anti-apoptotic, and anti-inflammatory effects in the cell. On the right, astaxanthin activates nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) by promoting its release from Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1) or Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 2 (Keap2). Following release, nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 translocates to the nucleus where it binds to antioxidant response elements (ARE), initiating transcription of antioxidant genes such as heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1) and NAD(P)H quinone dehydrogenase 1 (NQO1), thereby counteracting oxidative stress. In the apoptosis pathway, astaxanthin modulates the BAX/Bcl2 mitochondrial balance to inhibit cytochrome c release and subsequent activation of apoptotic mediators such as caspase three and caspase nine. By suppressing cytochrome c release, astaxanthin prevents apoptotic cell death. Astaxanthin and heme oxygenase 1 also inhibit the phosphorylation and degradation of inhibitor of kappa B (IkB), thereby blocking the nuclear translocation of nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells components p65 and p50. This inhibition suppresses the expression of inflammatory mediators, including interleukin 6 (IL6), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha), macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF), and intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM1). The flow from inflammation to apoptosis and oxidative stress is depicted by arrows, highlighting the interplay between these processes. Yellow boxes represent processes or regulatory elements, while colored rectangles represent proteins or genes. Blue indicates inflammation, yellow indicates apoptosis, and pink indicates oxidative stress to provide visual distinction among pathways. AXT astaxanthin, Nrf2 nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2, Keap1 Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1,; Keap2 Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 2, ARE antioxidant response elements, HO-1 heme oxygenase 1, NQO1 NAD(P)H quinone dehydrogenase 1, IL6 interleukin 6, TNF-alpha tumor necrosis factor alpha, MIF macrophage migration inhibitory factor, ICAM1 intercellular adhesion molecule 1, IkB inhibitor of kappa B, p65 and p50 subunits of nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells, BAX and Bcl2 pro- and anti-apoptotic proteins.

The compound’s distinct molecular structure enables it to maintain oxidant/antioxidant equilibrium, providing additional tissue protection68. AXT’s oxidative stress prevention mechanisms involve several pathways: it stimulates Nrf2/ARE, reduces p-ERK/ERK ratio, and enhances NQO-1 and HO-1 production. The Keap1-Nrf2-ARE system plays a crucial role in cellular antioxidant responses60. The compound also functions through PI3K/Akt pathway regulation69. Under hyperglycemic conditions, AXT protects photoreceptors from oxidative damage and reduces apoptosis by activating the PI3K/Akt/Nrf2 pathway. It also preserves retinal ganglion and Müller cells by increasing HO-1 levels. The Nrf2-ARE pathway is particularly important in strengthening cellular oxidative stress resistance (Fig. 2)60,70. During normal conditions, Nrf2 interacts with Keap1, but under oxidative stress, activated Nrf2 separates from Keap1, moves to the nucleus, and binds to ARE, promoting Phase II enzyme expression, including HO-1 and NQO135,63.

Interestingly, AXT exhibits prooxidant characteristics, generating small amounts of ROS that trigger HO-1 expression and modulate GSH-Px through ERK-Nrf-2/HO-1 signaling35. These ROS levels are harmless, as pure AXT promotes cell proliferation, enhances GSH-Px and SOD activity, and protects HUVECs from H2O2-induced oxidative stress35. Nrf2 activation by AXT supports retinal pericyte survival and triggers the Nrf2-ARE pathway, leading to increased HO-1 and NQO1 expression. This helps reduce oxidative damage and protects photoreceptor cells from glucose-induced apoptosis, particularly under high glucose conditions (e.g., 35 mM), which are known to elevate intracellular ROS levels significantly (Fig. 2)71. AXT prevents apoptosis by inhibiting various factors, including caspase 3,9, cytochrome c, p-ERK/ERK, and the Bax/Bcl2 ratio60,70. In spinal cord ischemia-reperfusion injury, AXT shows therapeutic potential by activating the PI3K/Akt/GSK-3β pathway72, which provides neuroprotection through apoptosis inhibition and cell proliferation promotion69.

Oral consumption of AXT

Despite astaxanthin’s (AXT’s) numerous potential applications, its practical use faces significant constraints due to poor dissolution characteristics in GI fluids. Studies indicate that AXT’s oral bioavailability is notably restricted, with only 10–50% of the administered dose being absorbed, primarily due to its limited solubility in both aqueous environments and blood lipid components like triglycerides73. This poor absorption by small intestinal epithelial cells classifies AXT as a compound with low bioavailability74. Various factors influence AXT’s oral bioavailability, including meal timing, the type of accompanying lipid-based foods, and lifestyle factors such as smoking habits75,76. The absorption mechanism of AXT follows dietary fat uptake patterns due to its lipophilic nature. Before micelle incorporation, the compound, typically present in esterified forms (mono- and diesters), must undergo hydrolysis by cholesterol esterase73. Although AXT has poor aqueous solubility, its hydrolyzed form’s polar end groups enable better absorption compared to other non-polar carotenoids77. Following micelle formation, AXT undergoes passive absorption into intestinal mucosal cells and becomes incorporated into chylomicrons. These chylomicrons enter the lymphatic system before reaching systemic circulation, where lipoprotein lipase breaks them down. The resulting chylomicron remnants are then processed by the liver and other tissues. Subsequently, HDL and LDL facilitate AXT’s transport to various tissues73.

Research has revealed distinct pharmacokinetic parameters for different AXT forms76. When administering 100 mg of free AXT orally, they observed a maximum concentration (Cmax) of 1.3 ± 0.1 mg/L occurring at 6.7 ± 1.2 h (tmax). The distribution volume was 0.40 ± 0.2 L/kg, with oral clearance at 0.013 ± 0.01 L/h and elimination rate of 0.042 ± 0.035 h−1, where h−1 is inverse hours as the elimination rate constant76. In contrast, administration of 100 mg AXT esters resulted in a lower Cmax (0.28 ± 0.12 mg/L) but showed a significantly longer elimination half-life of 52 ± 40 h−¹. For the ester form, the distribution volume increased to 2.0 ± 1.3 L/kg, with higher oral clearance (3.3 ± 1.1 L/h) and similar elimination rate (0.048 ± 0.03 h−1)78. These findings suggest that the additional hydrolysis step required for esterified AXT results in slower absorption kinetics. Research conducted by Okada et al. examined AXT’s oral bioavailability in 20 participants under two different timing conditions. Participants received soft capsules containing 4 mg AXT (formulated with 52 mg Haematococcus algal extract, olive oil, and Vitamin E) either 2 h before or 10 min after eating. The post-meal administration showed significantly higher absorption, with AUC(0–168) values 2.4 times greater than pre-meal consumption. Similarly, the AUC(0–∞) was 2.5 times higher in the post-meal group. This enhanced absorption was attributed to meal-induced bile secretion, which improved AXT’s digestive dispersion75.

Odeberg et al.‘s research demonstrated that lipid-based formulations significantly impact AXT absorption. Their study compared four formulations: a reference consisting of algae meal and dextrin in hard-shell capsules, and three lipid-enhanced versions—Formulation A (with palm oil), Formulation B (with glycerol mono- and dioleate), and Formulation C (combining glycerol mono- and dioleate with sorbitan monooleate). All lipid-based formulations showed superior bioavailability compared to the reference, as evidenced by higher AUC(0–∞) values73. Smoking’s impact on AXT bioavailability was also investigated by Okada et al. Their findings revealed lower blood AXT levels in smokers compared to non-smokers, with non-smokers showing 1.15 times higher AUC (0–∞). Smokers exhibited shorter AXT half-life (t1/2), suggesting accelerated elimination. This reduced t1/2 was attributed to cigarette smoke’s free radicals causing respiratory and circulatory oxidative stress, leading to faster AXT depletion as it counteracted the increased oxidative load75. Various strategies have been proposed to enhance AXT’s bioavailability, including post-meal administration, consumption with high-fat foods, and smoking cessation. Among these approaches, nano-formulation technology has emerged as a particularly promising solution. These specialized delivery systems offer multiple advantages, including improved solubility, enhanced stability, controlled release characteristics, and increased bioavailability79.

Modified nanoparticles for oral AXT delivery

Oral drug administration remains the most widely accepted delivery route, primarily due to its distinct advantages. This method offers convenience and flexibility in timing, leading to better patient adherence. Additionally, oral formulation manufacturing is more cost-effective as it does not require stringent sterile conditions and is less invasive than other routes80 (Fig. 3).

The depicted nanocarrier strategies aim to overcome astaxanthin’s low water solubility, poor stability, and limited bioavailability, thereby improving its pharmacological potential. Depicted at the top is a schematic of general nano-delivery systems incorporating astaxanthin, which are further classified into several major types: On the left, the nanoemulsion system is illustrated with a lipid core (shown in yellow) surrounded by surfactant molecules (represented as purple circles), within which astaxanthin (green dots) is solubilized. This structure facilitates improved dissolution of lipophilic compounds. In the middle, the liposome is represented with a bilayer of phospholipids (blue and yellow molecules) forming a sphere encapsulating an aqueous core. Astaxanthin is located within the bilayer, leveraging its amphiphilic nature to incorporate both water- and fat-soluble components. Next to the liposome, the niosome structure is shown, consisting of single-chain surfactant molecules forming a bilayer around an aqueous core, with astaxanthin similarly integrated within the membrane. Lower section diagrams illustrate solid lipid nanoparticle and nanostructured lipid carrier systems. Solid lipid nanoparticles are shown with a solid lipid core surrounded by surfactant and with astaxanthin distributed within, represented by green (and some red) dots in the yellow region. Nanostructured lipid carriers are depicted with a blended core of solid and liquid lipid (yellow), facilitating greater drug loading and sustained release as indicated by multiple green dots of astaxanthin. At the bottom right, the polymeric nanoparticle system is illustrated, comprising a polymeric matrix (gray and red strands) that encapsulates astaxanthin (green dots), stabilizing it and allowing for controlled drug release. Abbreviations and color codes: Astaxanthin: green dots; Lipid core or blended lipid core: yellow region; Surfactant: purple circles; Phospholipid or surfactant bilayer: blue/yellow head-tail structures; Polymeric matrix: gray with red polymer lines.

Lipid-based nanocarriers and nanoemulsions for enhanced delivery and bioavailability of AXT

Lipid-based nanocarriers, designed specifically for transporting fatty substances like AXT, contain lipids as their main component81. These carriers incorporate either fluid or solid lipid materials, such as waxes, triglycerides. Their appeal stems from their non-toxic nature, biodegradability, and their classification under generally recognized-as-safe (GRAS) status79. The incorporation of AXT into lipid-based nanoparticles offers multiple benefits. The enhanced bioavailability and superior kinetic release can be attributed to these carriers following metabolic pathways similar to dietary fats, allowing AXT to be released through simple diffusion82. Additionally, the chemical affinity between AXT and lipid-based nanocarriers enhances formulation stability. Moreover, these carriers demonstrate minimal toxicity owing to their biodegradable lipid constituents83.

Nanoemulsions represent a class of colloidal systems featuring emulsion droplets ranging from 10 to 200 nm, which resist sedimentation. These systems emerge from the combination of oil and aqueous phases, stabilized by an emulsifier. The emulsifying agent serves as a mediator between phases, contributing to emulsion stability alongside composition and droplet dimensions84,85,86.

Three distinct categories of nanoemulsions exist: water-in-oil (water droplets dispersed in oil), oil-in-water (oil droplets dispersed in water), and bi-continuous formations86. Their preparation employs either high-energy or low-energy approaches. High-energy methods utilize intense disruptive forces to create nano-sized droplets, including techniques like ultrasonication and high-pressure homogenization. Conversely, low-energy methods, such as phase inversion and spontaneous emulsification, rely on internal chemical reactions and gentle mixing87,88. Research has shown promising results in improving AXT’s pharmacokinetic properties through oil-in-water nanoemulsions. A study examining TAP-nanoemulsion (comprising tocopheryl polyethylene glycol succinate and AXT in peanut oil) demonstrated an 80% increase in AXT permeability through Caco-2 cells under simulated intestinal conditions. These cells were selected to model human intestinal absorption, as the small intestine is believed to be AXT’s primary absorption site. The enhanced cellular uptake, compared to conventional macroemulsions, was attributed to the smaller particle size, which facilitates better membrane penetration due to increased surface area89. A research study by Shen et al. evaluated AXT nanoemulsion uptake using various emulsifiers: Tween 20, Whey Protein Isolate (WPI), WPI-lecithin, Polymerized Whey Protein (PWP), PWP-lecithin, and lecithin. Although Tween 20-based nanoemulsion achieved the smallest particle size (193.87 ± 3.84 nm), it did not yield the highest cellular uptake. Instead, WPI-stabilized emulsion (203.81 ± 7.27 nm) demonstrated ~10-fold higher cellular intake compared to free AXT89. The researchers attributed this to whey protein-based carriers’ ability to deliver concentrated, bioavailable AXT, along with improved absorption by enterocyte cells due to digestive system interactions89.

Domínguez-Hernández and colleagues demonstrated enhanced AXT bioavailability in rats using nano-emulsified AXT prepared with canola oil and Tween 4090. The formulation showed a 7.5-fold increase compared to the reference solution. Using a low-energy method, they produced particles ranging from 1 to 200 nm, confirming that smaller particles provide greater surface area for bioactive release and absorption. The inclusion of Tween 40 was credited with improving AXT permeability90. These findings aligned with earlier research by Affandi et al., who compared AXT oral bioavailability across three particle-size formulations91. Their nanoemulsion combined AXT oil (16%), purified water (80% w/w), and emulsifiers (Tween 80 and lecithin). The nano-sized formulation demonstrated 1.5- and 2.2-times higher bioavailability compared to macro-sized and reference formulations, respectively. Maximum concentration (Cmax) values were: nano-sized (698.7 ± 38.7 ng/mL), macro-sized (465.1 ± 43.0 ng/mL), and reference oil (313.3 ± 12.9 ng/mL). While particle size significantly affected absorption and solubility, it did not impact elimination half-life (t1/2)92.

Nanoemulsion excels as an AXT delivery system due to effective lipophilic compound solubilization93. Its stability is enhanced by Brownian motion dominating gravitational forces, though destabilization occurs slowly88. However, instability can manifest through flocculation, sedimentation, creaming, and cracking. While gentle agitation can redistribute flocculated droplets, cracking represents irreversible phase separation86. Liposomes, consisting of natural or synthetic phospholipids in an aqueous phase, form spontaneously through hydrophobic interactions and amphiphilic phospholipid self-association. They can be prepared using reverse-phase evaporation or detergent removal techniques87,94. With diameters ranging from 400 to 2.5 mm, liposomes effectively transport lipophilic bioactives like AXT23. Their popularity as carriers stems from their ability to protect active ingredients and enhance drug targeting55. Their size enables passage through endothelial cell membranes via diffusion or lipid-mediated endocytosis10,94. Research by Sangsuriyawong et al. examined AXT-loaded liposomes’ bioavailability through Caco-2 cellular uptake studies. Their findings revealed that higher phospholipid content enhanced membrane adherence and intestinal barrier penetration due to lipophilic properties. Notably, liposomes with 70% phospholipid composition (PC) achieved 95.33% absorption in Caco-2 cells, while 23%-PC formulations showed negligible uptake. This difference was attributed to particle size variations: 70%-PC liposomes measured 0.14 μm versus 0.31 μm for 23%-PC liposomes.

The combination of lipophilicity and reduced particle size has been widely recognized as a crucial factor in enhancing intestinal barrier permeation and bioactive compound bioavailability10. Despite liposomes’ potential as bioactive carriers, they face several challenges, including rapid water-soluble drug leakage in blood, limited encapsulation efficiency, and storage stability issues55. These limitations led to the development of niosomes, an advanced vesicular system utilizing non-ionic surfactants. Niosome formation involves heat and physical agitation, creating closed bilayer vesicles where hydrophilic portions contact aqueous solvent while hydrophobic sections face outward. The vesicular structure is maintained by various forces, including van der Waals, repulsive, and entropic repulsive forces95. Niosomes can form unilamellar or multilamellar structures due to their hydrophilic, lipophilic, and amphiphilic components. These vesicles demonstrate resistance to enzymatic hydrolysis and acidic environments, capable of encapsulating both water-soluble compounds (in vesicular or bilayer surface aqueous phase) and lipid-soluble substances (in non-aqueous bilayer core)11,23. However, research on AXT incorporation into niosomes remains unexplored, presenting opportunities for future investigation. Solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs) represent a recent advancement in nanomedicine. These colloidal carriers comprise surfactant-stabilized biodegradable lipids, ranging from 50 to 1000 nm in diameter96. Nanostructured lipid carriers (NLCs), the second-generation lipid nanoparticles, differ from SLNs by incorporating both solid and liquid lipids in their matrix structure97.

The key distinction lies in their composition: SLNs contain lipids solid at room and physiological temperatures, while NLCs blend solid and liquid lipids98. Both systems can be manufactured using techniques such as high-pressure homogenization and microemulsion97. Their applications span diagnostics, the food industry, and nutraceutical delivery, particularly suitable for improving oral absorption of lipophilic drugs80. Research by Wang et al. demonstrated enhanced antioxidant properties of AXT-loaded SLNs in simulated gastrointestinal fluids. Their findings showed that SLN-encapsulated AXT displayed superior antioxidant activity at just 0.25 µg/mL, while free AXT required 10 µg/mL to show effects. ABTS assay results revealed that free AXT separated from the media, with its poor solubility likely causing reduced antioxidant activity99. Li and colleagues’ in vitro research highlighted AXT-loaded SLNs’ superior stability and release characteristics in simulated GI conditions compared to free AXT. While free AXT showed significant decomposition (68.3 ± 1.5%), SLN-encapsulated AXT maintained stability with <10% decomposition. The enhanced protection was attributed to AXT’s embedding in recrystallized lipid nucleation, offering better preservation than nanoemulsion systems100.

Despite SLNs’ advantages of modifiable release and straightforward incorporation, they face challenges in controlling drug expulsion during storage. NLCs were developed to address these limitations, featuring reduced lipid recrystallization that minimizes active ingredient expulsion101. The combination of solid and liquid lipids in NLCs creates structural imperfections, with liquid lipids providing a less crystalline arrangement. These imperfections create more space for drug incorporation compared to SLNs’ perfect crystalline structure102. Multiple studies have explored NLCs’ potential for oral AXT delivery. These carriers demonstrate enhanced chemical stability between lipophilic compounds and lipid-based carriers, with improved water-based product dispersibility and stability compared to SLNs83. Mao et al.‘s research demonstrated superior antioxidant activity of AXT-loaded NLCs through DPPH assay, achieving 100% free radical scavenging compared to 94% for free AXT. The study showed minimal loss of antioxidant properties post-NLC incorporation. The formulation maintained stable particle size in stomach conditions, demonstrating resistance to acidic environments and pepsin. While intestinal conditions increased PDI due to anionic components (bile salts, phospholipids, free fatty acids), these components potentially enhanced AXT absorption, suggesting improved bioavailability (Table 1)103.

Polymeric nanosystems

Chitosan-based nanoparticles represent another promising carrier system for AXT delivery. As the sole positively charged polysaccharide, chitosan facilitates electrostatic interactions with negative polyelectrolytes in colloidal nanoparticle formation12. These nanoparticles can be prepared through various methods, including ionic gelation, cross-linking, and solvent evaporation104,105. Their appeal stems from their biodegradability, safety profile, and enhanced absorption through Peyer’s patches83.

Hu et al. developed an innovative approach using complex chitosan–casein-oxidized dextran nanoparticles through cross-linking12. These 120 nm particles demonstrated improved AXT dispersibility in PBS and enhanced GI fluid stability. The enhanced properties resulted from covalent bonding between oxidized dextran’s aldehyde groups and the amino groups of stearic acid–chitosan conjugate and sodium caseinate via Schiff base reaction. The formulation achieved 85.6% antioxidant activity in ABTS assays, significantly outperforming free AXT, whose poor PBS dispersibility limited radical interaction. However, potential oral administration challenges exist due to hepatic dextran-1,6-glucosidase potentially degrading oxidized dextran before reaching targets12.

Kim and colleagues investigated chitosan–tripolyphosphate nanoparticles created via ionic gelation for AXT delivery104. Their research demonstrated sustained AXT release in simulated GI conditions, indicating formulation stability. In vivo FRAP assays revealed distinct antioxidant activity patterns: free AXT showed a rapid initial increase (106.68 ± 17.93 µmol/L) followed by a decline, while nanoparticle-encapsulated AXT exhibited slower initial activity (85.33 ± 22.45 µmol/L) but maintained consistent levels over 4 h. Free AXT’s declining activity was attributed to poor alkaline solubility. The study suggested that chitosan-based nanoencapsulation could overcome these limitations, providing enhanced bioavailability and sustained release of oral AXT104.

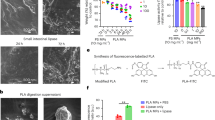

Zhu et al.‘s recent research introduced a novel PEG-grafted chitosan carrier for AXT using solvent evaporation. Their findings showed significant intestinal absorption (20 µg/mL) of encapsulated AXT, while free AXT showed no absorption due to insolubility in sodium carboxymethylcellulose-containing intestinal perfusion fluid. In vivo studies revealed dramatically higher Cmax values for chitosan-encapsulated AXT (2264.03 ± 64.58 ng/mL) compared to free AXT (231.45 ± 7.47 ng/mL)106. The AUC(0–60) of encapsulated AXT exceeded free AXT by 6.2 times, demonstrating significantly enhanced bioavailability with PEG-grafted chitosan encapsulation105. Chitosan-based nanoparticles effectively address AXT’s poor bioavailability challenges, including intraperitoneal injection limitations. These carriers provide sustained release, GI degradation protection, and improved core solubility, enabling targeted delivery and enhanced bio-accessibility23. The enhanced water solubility of these particles, resulting from their greater surface area, enables better penetration through cell membranes, thereby enhancing oral bioavailability104,105. Various techniques, including nanoprecipitation, anti-solvent precipitation, and emulsion solvent evaporation, can be employed to create PLGA-based AXT nanoparticles107,108. Liu and colleagues created novel core–shell nanoparticles containing AXT that combined chitosan oligosaccharides with PLGA, utilizing anti-solvent precipitation techniques for the core formation and electrostatic deposition for the chitosan coating. Their findings revealed quick release in acidic gastrointestinal conditions, characterized by an initial burst release of AXT located on the surface, followed by continuous release from the core in both stomach (pH 2.1) and small intestinal (pH 7.4) environments. The formulation exhibited stability at room temperature for 72 h without showing color alterations or separation. The addition of the chitosan oligosaccharide coating improved dispersibility in water, which enhanced solubility and indicated potential for improved oral bioavailability (Table 2)109.

Biomedical targets and therapeutic applications of AXT nanoparticles

AXT and diabetes mellitus

Diabetes mellitus, commonly referred to as diabetes, encompasses various metabolic conditions characterized by sustained elevated blood glucose levels. Current statistics indicate approximately 463 million individuals are affected worldwide, with projections suggesting an increase to 578 million within the next decade110. Hyperglycemia-induced reactive oxygen species (ROS) generate oxidative stress, significantly impacting diabetes progression. AXT exhibits exceptional antioxidant capabilities, counteracting oxidative damage through multiple pathways, including free-radical neutralization, inhibition of lipid peroxidation, and singlet oxygen deactivation. Unlike other carotenoids, AXT’s unique polar structure enables seamless integration into cellular membranes without disrupting their integrity, effectively reducing lipid hydroperoxide concentrations111. Research has demonstrated AXT’s ability to boost mitochondrial function by decreasing mitochondrial ROS production, thereby enhancing ATP generation and respiratory activities112. Diabetic nephropathy, a microvascular complication affecting both Type I and II diabetes patients, manifests through kidney tubule and glomerular damage. Key indicators include decreased glomerular filtration rates and tubular epithelial cell deterioration113. Given oxidative stress’s crucial role in nephropathy development, AXT’s potent antioxidant properties make it particularly promising for therapeutic intervention. Regarding diabetic complications, retinopathy emerges as a gradually progressing condition marked by enhanced inflammation, compromised antioxidant enzyme activity, retinal cell metabolic alterations, microvascular injury, oxidative damage to retinal and capillary cells, and activated retinal cell autophagy114,115,116 Experimental studies with rats have shown AXT’s preventive potential against retinopathy, demonstrating reduced oxidative stress and inflammatory markers while boosting antioxidant enzyme levels117. Research on human retinal pigment epithelial cells revealed AXT’s capacity to mitigate high glucose effects by reducing advanced glycation end products118, ROS, and lipid peroxidation119. Additionally, Khedher and colleagues documented AXT’s inhibitory effect on aldose reductase, an enzyme central to retinopathy development120.

Diabetic neuropathy manifests through various neurological complications, including neural irregularities, brain cell death, impaired hippocampal-related cognitive functions, and altered neuronal behavior121 These conditions primarily stem from oxidative stress, inflammatory mediators, and activated apoptotic pathways. Research demonstrates that AXT administration provides protective and ameliorative effects against neuropathy by enhancing antioxidant enzyme function, lowering inflammatory molecule levels, preventing cellular apoptosis122, improving neurological responses in STZ mice57, and reducing cognitive impairment through oxidative stress and inflammation suppression in diabetic mouse models123. Diabetes can lead to various heart-related conditions, collectively known as diabetes-associated cardiomyopathies, which develop from complications such as blood clotting, hardening of arteries, blood vessel damage, and platelet clumping. These conditions are primarily caused by high blood sugar levels and oxidative stress124,125. The natural compound AXT helps counteract these effects through several pathways: reducing oxidative damage and inflammation while exhibiting anti-inflammatory and blood-thinning characteristics126, influencing redox processes, controlling blood vessel constriction, blood pressure, and blood flow properties, and lowering levels of low-density lipoprotein (LDL)127,128. In terms of kidney disease, AXT’s protective effects on kidney function have been well-established through numerous studies. Research demonstrates increased protein in urine and decreased markers of oxidative stress in diabetic db/db mice after 12 weeks of AXT administration129. Further beneficial effects include inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), transforming growth factor beta (TGFB), and reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in mesangial cells exposed to high glucose levels130, restoration of normal creatinine and uric acid concentrations, decreased urea and glomerular enlargement in diabetic rat models, and general enhancement of kidney function131. AXT also increases antioxidant enzyme expression and maintains kidney and plasma antioxidant status, thereby reducing diabetes-related renal complications and preventing renal fibrosis by limiting ECM component accumulation and protecting against oxidative damage through Nrf2-ARE transcription factor activation132.

Nevertheless, AXT’s limited solubility and stability compromise its antioxidant efficacy and bioavailability. Recent research targeting diabetic nephropathy introduced a novel liposomal delivery system encapsulating AXT, specifically designed to target glomerular mesangial cells via glucose transporter 1133. This glucose-modified liposomal system successfully penetrates the glomerular mesangial cell membrane through glucose transporter 1, effectively neutralizing oxidative stress-induced ROS134. Drug release studies conducted at varying pH levels—acidic conditions simulating lysosomal environment and phosphate buffer saline with 10% fetal bovine serum representing blood conditions—demonstrated accelerated release in acidic environments while providing enhanced protection for the drug molecules.

AXT, brain, and neurologic disorders

Researchers have developed numerous approaches to enhance drug penetration across the blood–brain barrier135,136,137,138,139,140,141. These methods can be categorized into two main groups: invasive and non-invasive techniques. Invasive approaches encompass several methods for direct drug delivery to specific brain regions. These include intracerebroventricular injection, which involves direct drug administration into the cerebrospinal fluid142,143,144. Another technique, convection-enhanced delivery, specifically targets brain tumors by creating small skull openings to insert multiple cannulas at various angles, enabling direct drug administration to the tumor site. Ultrasound technology represents another innovative approach, where microscopic bubbles are introduced into the bloodstream. Using MRI guidance, injections are precisely targeted to specific brain regions. Ultrasound waves, transmitted through a head-mounted cap, cause bubble vibrations that temporarily open tight junctions, creating pathways for drug entry145,146,147. Additionally, mechanisms involving Aβ deposition in cerebrovascular cells have shown potential in enhancing AXT effectiveness, reducing drug side effects, and increasing expression of crucial brain genes148. Osmotic disruption, another invasive method, employs hypertonic solutions to cause cerebrovascular endothelial cell shrinkage, disrupting blood–brain barrier tight junctions (Fig. 4)149,150. While inhalation offers an alternative administration route, its effectiveness is limited by poor olfactory lip absorption, resulting in suboptimal drug delivery to target sites151,152 Studies have shown that these delivery methods often demonstrate inadequate success rates153,154. The osmotic pressure approach to opening tight junctions presents significant risks, as it may allow toxins and unwanted substances to enter the brain alongside therapeutic agents. This has prompted increased focus on non-invasive alternatives. While increasing drug molecule lipophilicity can enhance brain penetration, it also affects the drug’s metabolism and distribution throughout the body. This often necessitates higher dosing, potentially leading to increased side effects155,156,157.

A comparative overview of invasive and non-invasive approaches developed to facilitate the delivery of therapeutics across the blood–brain barrier, a critical challenge in central nervous system drug development, is provided in this figure. The top section depicts invasive methods, including trans-cranial, trans-nasal, and convection-enhanced delivery strategies. A detailed schematic illustrates how osmotic disruption, commonly using mannitol at a concentration of 25%, leads to the shrinkage of endothelial cells lining cerebral blood vessels. This process loosens tight junctions formed by junctional adhesion molecule, occludin, and claudin proteins, enabling the passage of large or hydrophilic drugs into the brain parenchyma. Red indicates the restrictive tight junctions in their normal state, while blue highlights their loosened configuration after osmotic disruption. To the right, stylized human head and brain images illustrate the access routes for each invasive approach. The trans-cranial method involves direct injection through the skull. The trans-nasal method leverages the olfactory and trigeminal neural pathways. Convection-enhanced delivery uses a pressure gradient to distribute therapeutic agents directly within the brain tissue. The lower section presents non-invasive methods, which seek to traverse the blood–brain barrier without physically disrupting it. Here, the barrier is shown as a series of purple membrane layers impeding the passage of unmodified drugs (visualized as green spheres with a red hexagonal “stop” sign). Chemical transformation techniques, including prodrug formation or receptor-mediated targeting, modify drug molecules for improved permeability or receptor binding. Chemical modification is further illustrated: drug molecules bind to specific cellular receptors, undergo endocytic uptake (binding, fusion, release), and are subsequently liberated inside the target cell. Nanoparticle-based strategies are depicted as green clusters navigating the barrier via endocytosis. Drug-loaded nanoparticles enter cells by endocytic uptake, after which drug release can occur either by lysosome–endosome fusion or via recycling of the endosome structure. Abbreviations and color codes: JAM: junctional adhesion molecule; Purple spheres and lines: membrane structure and tight junctions; Red hexagon: “stop” or barrier to entry; Green spheres: drug molecules; Blue and pink: invasive and non-invasive pathways; Endosome and lysosome: cellular vesicles involved in drug trafficking.

High molecular weight compounds, including peptides, proteins, and genetic material, face significant challenges in crossing the blood–brain barrier. Their environmental instability leads to rapid metabolism before reaching the brain. Interestingly, even drugs with optimized molecular weight and lipophilic characteristics that naturally traverse the blood–brain barrier often face rapid expulsion back into circulation due to powerful efflux pumps155. Nanotechnology presents a promising solution for enhancing brain drug delivery without compromising blood–brain barrier integrity. One innovative approach employs the “Trojan horse” strategy, where drugs are encapsulated within DNA structures, effectively bypassing cellular efflux mechanisms. Additionally, drug carriers can be designed to interact specifically with endothelial cell receptors, facilitating brain parenchymal entry through receptor-mediated transport. Nanotechnology-based delivery systems offer dual advantages: improved therapeutic efficacy and minimized off-target effects. Various nanoparticle types, including metallic, lipid-based, and polymeric formulations, have been explored for brain drug delivery. However, successful delivery depends critically on blood–brain barrier status and nanoparticle dimensions. A major challenge remains the comprehensive assessment of neuronal toxicity in clinical and in vivo settings158,159,160,161,162,163,164,165.

Neurodegenerative disorders typically develop through inflammatory cascades, oxidative stress, and apoptotic pathways, leading to neuronal degradation151. Antioxidants demonstrate cognitive benefits through multiple mechanisms, including inflammation reduction, NF-κB regulation, and cytokine suppression. AXT, a potent antioxidant, exhibits restorative, antiseptic, antiaging, and anti-inflammatory properties, making it valuable for treating various neurological conditions, including neuropathic pain, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, autism, and depression166. AXT’s distinctive chemical structure facilitates blood–brain barrier penetration, enabling direct access to its primary target organ. Research has confirmed its ability to modulate immune responses, reduce inflammation, and address neurodegenerative conditions167. Studies have linked elevated IL-6 levels to multiple sclerosis progression168. leading to blood-brain barrier disruption, demyelination, and neuroinflammation. Research has demonstrated AXT’s efficient blood-brain barrier crossing capability, enabling central nervous system protection against both acute and chronic neuronal damage57.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) development involves Th1 cytokines, and AXT modulates immune responses by promoting Th1 to Th2 cell conversion. Research indicates that AXT supplementation effectively prevents, heals, and reduces inflammation and neuronal damage associated with multiple sclerosis. Studies have demonstrated AXT’s capacity to minimize ischemic brain damage in mammals through apoptosis prevention and ROS suppression. It offers protection against hypertension-related injuries, vascular oxidation, and cerebral thrombosis. Additionally, AXT’s neuroprotective properties and stroke risk reduction are achieved through ROS suppression and Nrf2-ARE pathway activation, suggesting potential benefits for patients susceptible to ischemic events169,170,171. In Alzheimer’s disease, when amyloid-β peptide oligomers build up, they decrease type-2 ryanodine receptor expression and enhance mitochondrial reactive oxygen species, ultimately causing neuronal death. Research shows that AXT shields neurons from these harmful oligomers by modulating type-2 ryanodine receptor gene expression62. AXT significantly diminishes amyloid-β peptide oligomers, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, nitrite, acetylcholinesterase levels, oxidative stress, and the activities of glycogen synthase kinase-3β and insulin receptor substrate-S307 in the hippocampus, while also preventing hippocampal insulin resistance linked to Alzheimer’s disease172. A comparative study examining pure AXT versus an AXT-docosahexaenoic acid combination in APP/PSEN1 double-transgenic mice revealed that the combination more effectively managed oxidative stress, regulated inflammasome expression/activation, decreased Tau hyperphosphorylation, and inhibited neuroinflammation173.

Diabetic individuals suffering from depression exhibit increased cognitive dysfunction associated with elevated levels of glycosylated hemoglobin, acute phase reactive protein, interleukin-6, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha174. Research has identified mood disorders as potential risk factors for developing Alzheimer’s disease175. Recent studies indicate that managing brain inflammation and minimizing nerve damage may help alleviate depression symptoms in diabetic mice176. The reduction of inflammatory cytokines appears to be essential in the treatment of depressive disorders177. Natural supplements have demonstrated effectiveness in improving mood and reducing anxiety/stress through inhibition of inflammatory processes178. Experimental studies revealed decreased depression severity in mice administered oral AXT (25 mg/kg) for a period of 10 weeks179. Furthermore, daily consumption of a shrimp oil supplement containing 0.2 mg of AXT for 7 weeks was found to enhance learning abilities, working memory, and reduce depressive symptoms180. AXT has demonstrated the ability to enhance human adipose-derived stem cell survival and proliferation, potentially improving their transplantation efficacy in treating MS, a debilitating central nervous system condition181.

AXT and cancers

Cancer fundamentally involves malignant cell proliferation resulting from specific genetic alterations affecting cell cycle regulation, survival mechanisms, motility, and blood vessel formation. Cell cycle progression is regulated by cyclin proteins, whose fluctuating levels activate E/CDK2, D/CDK6, and D/CDK4 complexes, leading to RB phosphorylation and subsequent cell proliferation. Mutations or amplifications in cell cycle regulatory genes can trigger uncontrolled proliferation, as exemplified by cyclin D1 activation182. Research demonstrates that AXT arrests the cell cycle at the G0/G1 phase and inhibits cyclin D1 expression while simultaneously enhancing p53, p27, and p21WAF-1/CLP1 expression. Apoptosis represents a crucial cancer defense mechanism, involving nuclear membrane degradation, cytoplasmic breakdown, and cellular fragmentation, followed by phagocytic removal. Key apoptotic regulators include Bim, Bcl-2, Bcl-XL, Bak, Bax, Bad, p53, and Mcl-1, with Mcl-1, Bcl-2, and Bcl-XL serving as anti-apoptotic factors, while Bim, Bad, Bak, and Bax promote apoptosis183,184,185.

Studies reveal AXT’s dual action in downregulating anti-apoptotic proteins while upregulating pro-apoptotic proteins, promoting cytochrome c and Smac/Diablo release. The pathway involves Bcl-2-mediated cytochrome c release, triggering caspase-9 and subsequent caspase-3 activation, ultimately inducing mitochondrial apoptosis186,187. In the LS-180 cell line, AXT demonstrates antiproliferative effects by enhancing Bax and caspase 3 expression while reducing malondialdehyde and bcl2 levels. It also shows promise in prostate cancer treatment through alpha-reductase inhibition, with documented anticancer effects across multiple cancer types, including prostate, liver, colon, lung, and breast188,189,190,191,192,193. Contemporary drug delivery systems increasingly incorporate nanoparticles, with various materials serving as enhancers to improve treatment efficacy, stability, and safety. AXT’s capability to reduce metal salts enables nanoparticle formation suitable for biological applications. Studies of AXT-reduced gold nanoparticles (AXT-Au NPs) demonstrate significant cytotoxicity against MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells, inducing apoptotic morphology. These nanoparticles show particular promise in photobased diagnostics and therapy due to their near-infrared absorption properties, enabling deep tissue penetration and efficient photothermal energy conversion194.

Cancer treatment success rates significantly improve with early detection. Photoacoustic imaging, a hybrid technique utilizing the photoacoustic effect, offers high-resolution, sensitive cancer diagnostics with superior cost-effectiveness and tumor contrast compared to conventional imaging methods. AXT’s 490 nm absorption peak makes it an effective photoabsorbing agent for enhanced photoacoustic tumor detection. Research by Nguyen et al. demonstrated AXT’s effectiveness as a biocompatible photoacoustic contrast agent for bladder tumor identification195,196,197,198. Additional studies have explored AXT-conjugated bovine serum albumin with polypyrrole nanoparticles for phototherapy and cancer detection. Furthermore, researchers developed an AXT-alpha tocopherol nanoemulsion using spontaneous and ultrasonication emulsification, demonstrating significant anticancer, antimicrobial, and wound-healing properties across multiple cancer cell types194.

Solid lipid nanoparticles have emerged as promising oral delivery systems for vitamins due to their biocompatibility with lipid matrices and in vivo degradability. While AXT demonstrates superior potency compared to β-carotene and vitamin E in treating various disorders, its oral administration faces challenges, including light sensitivity, oxygen-induced decomposition, and poor water solubility. These limitations have been addressed through solid lipid nanoparticle encapsulation. A Tween 20 esters and glycerol-based delivery system achieved 163–167 nm particle diameter with ~89% encapsulation efficiency, demonstrating sustained AXT release in simulated GI conditions99,100. Another innovative approach utilized chitosan oligosaccharide-coated poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) particles for AXT delivery. Two poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid) variants with different lactide:glycolide ratios (50:50 and 25:75) were evaluated for physicochemical properties and drug-delivery potential. The chitosan oligosaccharide coating created pH-responsive behavior, increasing release rates in acidic conditions. This system demonstrated improved water dispersity and enhanced bioavailability compared to pure AXT and uncoated formulations109.

AXT and dermatological disorders

The skin functions as the primary protective barrier between organisms and their environment, with the stratum corneum serving as the principal obstacle for medication absorption. Active substances can penetrate the skin through two primary pathways: trans-appendageal and trans-epidermal routes. The trans-epidermal route, which facilitates skin permeation, consists of intercellular (paracellular) and transcellular (polar) pathways. For active antioxidants, the intercellular pathway represents the primary route of penetration into the skin, potentially reaching deeper layers199,200,201. Nanotechnology plays a crucial role in enhancing dermal drug delivery by offering several advantages: regulated drug release, increased drug loading potential, improved storage stability, and sustained delivery leading to optimal drug concentrations. The stratum corneum’s thickness of 10-40 μm presents a significant barrier, typically allowing only molecules with molecular weights below 500 g/mol to reach the dermis. The irregular arrangement of cells in this layer creates a complex path for drug penetration199,202,203.

While various physical and chemical methods have been developed to enhance transdermal drug delivery, many are expensive and can cause irritation. Innovative nanotechnology-based approaches for topical application with controlled release have proven particularly beneficial for medications with limited water solubility and brief half-lives. Beyond therapeutic applications, nanoparticles and nanocarriers have become integral to cosmetics, with liposome-containing moisturizers first appearing approximately four decades ago204,205,206,207,208. Given the skin’s constant exposure to environmental factors, it requires dedicated care and protection. Regular skincare utilizing cosmetics enriched with nutraceuticals helps maintain skin elasticity, improve texture, and enhance smoothness, contributing to overall skin health209. Transdermal and topical drug administration faces significant challenges due to the stratum corneum barrier, which restricts the passage of bioactive compounds, particularly those with smaller molecular weights. Microneedle patch technology has emerged as an innovative solution to penetrate this barrier. These devices, featuring microscopic needle arrays, enable non-invasive delivery of substances into the dermal layer199,210. Currently, research on AXT delivery via microneedles remains unexplored, presenting an opportunity for future investigations.

In cellular systems, homeostasis depends on maintaining equilibrium between reactive oxygen/nitrogen species production and antioxidant defense mechanisms. Disruption of this balance can alter cellular structure and function. Skin exposed to excessive oxidative stress exhibits various aging signs, including wrinkles, loss of radiance, texture irregularities, dehydration, and diminished elasticity. Ultraviolet radiation penetrates skin tissues, triggering oxidative stress that damages DNA, proteins, and lipids, potentially leading to mutations, collagen breakdown, inflammation, and carcinogenic changes211,212,213. AXT supports skin health through multiple pathways, including antioxidant activity, inflammation reduction, immune system enhancement, and DNA repair promotion214,215,216. Research has demonstrated AXT’s ability to enhance skin parameters, including elasticity, texture, hydration, and reduce aging indicators. Its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties suggest potential benefits in skin cancer prevention217,218,219.

Clinical studies have explored AXT’s cosmetic applications. One trial involving 11 female participants using AXT-containing cream showed improved skin hydration and elasticity after 3 weeks, with noticeable wrinkle reduction in some subjects. Another study of 49 women aged 45–50 years, receiving 4 mg AXT for 6 weeks, reported enhanced skin characteristics in over half the participants. At the molecular level, AXT activates cellular antioxidant mechanisms through the Nrf2 pathway modulation220,221. The Keap1–Nrf2–ARE pathway serves as the primary defense mechanism against oxidative stress. Under normal conditions, Keap1 protein regulates Nrf2 transcription factor by binding and facilitating its degradation in the cytoplasm. During oxidative stress, modifications to Keap1’s cysteine residues reduce Nrf2 degradation, enabling its nuclear translocation. Once in the nucleus, Nrf2 binds to ARE sequences, triggering the expression of antioxidant enzymes, including superoxide dismutase, catalase, and peroxiredoxin, which are crucial for ROS neutralization35,222.

AXT demonstrates significant immunomodulatory effects. Studies have shown enhanced immunoglobulin production in human lymphocytes and improved T and NK cell cytotoxicity following AXT exposure215,223. A clinical trial involving young female college students receiving daily AXT supplementation for eight weeks revealed enhanced immune markers, including increased IFN-γ and IL-6 production, improved NK cell activity, and elevated LFA-1 expression. Additionally, researchers observed decreased DNA damage biomarkers alongside enhanced immune function224. UV radiation generates ROS and free radicals like hydroxyl and singlet oxygen, which can damage DNA structure and base composition. AXT’s antioxidant properties help prevent free radical accumulation and subsequent DNA damage. Research in tissue engineering and wound healing has demonstrated promising results with AXT, particularly when combined with polysaccharides like chitosan and collagen. Studies showed that AXT-collagen combinations accelerated wound healing in rats by up to 50% compared to control groups63,216,225.

AXT may influence DNA repair mechanisms and has demonstrated protective effects against UV-induced DNA damage in human melanocytes and CaCo-2 cells. Skin aging manifestations, including wrinkles and elasticity loss, result from changes in extracellular matrix components like collagen, elastin, and glycosaminoglycans. UV-induced ROS stimulates matrix metalloproteinases, leading to collagen degradation. AXT inhibits metalloproteinase expression and has shown protective effects against UV damage in human dermal fibroblasts58,226,227,228. AXT exhibits anti-inflammatory properties by inhibiting NF-κB activation and inflammatory mediator production. A 30-day study on buffaloes demonstrated reduced expression of inflammatory markers IL-6, TNF-α, and IFN-γ in peripheral blood mononuclear cells compared to controls. AXT’s ability to reduce nitric oxide and cyclooxygenase levels suggests potential applications in anti-inflammatory drug development229,230.

AXT and ophthalmologic diseases

Research demonstrates AXT’s capacity to shield retinal cells from oxidative stress and UV radiation while alleviating eye strain symptoms67,231. Studies confirm its ability to suppress ROS generation and prevent retinal cell death. During retinal ischemia, increased NF-κB production triggers retinal inflammation. Glial cells contribute significantly to inflammatory processes in retinal disorders by secreting inflammatory cytokines, particularly IL1β and TNFα. These cytokines trigger COX2 and iNOS gene expression, resulting in NO and PGE2 inflammatory mediator production. AXT functions by inhibiting NF-κB activation and suppressing COX2 and iNOS expression232,233,234,235,236. Local application of AXT effectively reduces UV radiation damage, with studies showing significantly reduced apoptotic cell counts in AXT-treated irradiated corneas. Topical administration has proven more effective than systemic delivery for ocular surface protection. Additionally, AXT reduces retinal inflammation by decreasing TNF and IL1β expression. Through enhanced expression of p-Akt, p-mTOR, and Nrf2, while reducing caspase-3 expression, AXT prevents retinal ganglion cell and pigment epithelium apoptosis, offering protection against glaucoma and age-related macular degeneration (AMD)232,237,238.

AXT demonstrates protective effects against elevated intraocular pressure-induced retinal damage and inhibits glaucomatous retinal deterioration231,239. Current AMD treatment primarily relies on macromolecular angiogenesis inhibitors, such as aflibercept (97 kDa), pegaptanib (50 kDa), and ranibizumab (48 kDa), which target endothelial vascular growth factor associated with choroidal neovascularization. While intravitreal injections are commonly used to deliver these biomolecules to the posterior segment, this method carries risks including ocular infections, patient discomfort, elevated intraocular pressure, and retinal artery blockage240. Given the early stage of macromolecular drug delivery development, researchers are actively exploring alternative delivery methods, with particular emphasis on small-molecule ocular drug delivery. AXT, being a small molecule, shows promise in treating ocular conditions, particularly AMD, though it must overcome various barriers to reach posterior eye segments241. Studies indicate AXT’s potential in reducing ocular inflammation by modulating the mRNA and protein expression of inflammatory markers, including TNF-α, IL-1β, and HMGB1242.

While topical ocular medications like eye drops and ointments offer advantages in terms of minimal invasiveness and user convenience, they face several obstacles. The rapid elimination of eye drops, coupled with limited tear capacity, poses significant challenges. This is particularly problematic for high molecular weight and hydrophilic drugs, which exhibit poor permeability compared to their small, lipophilic counterparts. Drug transport to anterior and posterior segments occurs through corneal and non-corneal pathways, each presenting distinct permeation barriers243. Key considerations in ocular drug delivery include molecular size, weight, permeability characteristics, and hydrophilic-lipophilic balance, along with the delivery system design. While topical administration remains preferred for treating anterior eye conditions affecting the cornea, sclera, or lens, posterior segment drug delivery requires innovative approaches to overcome ocular tissue barriers. Nanotechnology-based formulations have emerged as one of the most promising solutions, offering potential for in situ delivery and controlled release while minimizing systemic side effects.

AXT, characterized as a lipid-soluble keto-carotenoid, has demonstrated effectiveness in treating various oxidative stress-related ocular conditions, including AMD and dry eye associated with aging, allergies, and inflammatory conditions23,244. For optimal therapeutic efficacy, AXT must reach retinal epithelial cells, its primary target site. While eye drops represent the most practical and user-friendly administration route, developing an effective delivery system for the poorly water-soluble AXT remains crucial245. Nano-scale liposomes present an effective solution, capable of encapsulating hydrophobic AXT and modifying its surface charge characteristics to facilitate posterior ocular tissue delivery. Studies using AXT-loaded liposomes in dry eye models have demonstrated reduced cell death, decreased ROS production, and inhibition of aging markers. Research indicates that positively charged liposomes enhance localized AXT delivery, with cationic liposomes showing superior cellular affinity compared to neutral variants, making them promising nanocarrier candidates246.

Drug penetration via topical administration can be enhanced using mucus-penetrating delivery systems. In vivo studies of mucus-penetrating nanoparticles have shown improved drug diffusion throughout ocular tissues, including both surface and posterior segments. Additionally, drug transport to posterior eye segments can be facilitated by conjugating nanoparticles with biological molecules such as cell-penetrating peptides, proteins, monoclonal antibodies, genes, and oligonucleotides247,248. Various nanotechnology-based carrier systems, including nanoparticles, liposomes, nanomicelles, nanosuspensions, and dendrimers, are being investigated for ocular drug delivery applications249. While nanoformulations demonstrate superior ability in overcoming ocular barriers compared to conventional delivery methods for AXT, continued research is needed to develop novel delivery systems that can further enhance AXT’s stability, solubility, and bioavailability23.

Challenges and limitations

Current research indicates that nano-formulation technology could significantly enhance AXT’s oral bioavailability. Multiple studies, both in vitro and in vivo, have evaluated the effectiveness of various nanoparticle formulations of AXT, documenting their pharmacokinetic characteristics to guide future developments. Different delivery systems, including nanoemulsions, liposomes, SLN, chitosan-based, and other polymeric nanoparticles, have been developed. These innovative formulations demonstrate improved cellular permeability and absorption, leading to enhanced oral bioavailability, with no reported toxicity to date. However, the widespread application and commercialization of AXT nano-formulations face several obstacles. The limited number of comprehensive scientific and clinical studies presents a significant challenge. Particularly, toxicological data for AXT-loaded nano-formulations remain insufficient, with current findings primarily derived from in vitro research250,251. To address these limitations, more extensive scientific and clinical investigations are essential to provide a comprehensive understanding of AXT-loaded nanoparticles, including their practical applications, therapeutic efficacy, and safety profiles. Given the rapid expansion of nano-formulation research, appropriate regulatory frameworks for AXT-loaded nanoparticles must be established250,251. The continuing advancement in AXT nano-formulation technology is expected to facilitate the development of optimal delivery systems for both nutraceutical and pharmaceutical applications. Furthermore, this research could lead to potential therapeutic applications in critical conditions such as cancer, supported by a thorough understanding of the formulation’s pharmacotherapeutic properties, pharmacokinetics, and toxicological profiles.

Future perspectives