Abstract

This study investigated the role of offline consolidation, specifically sleep, in transforming memories strengthened by retrieval practice into stable long-term representations. Forty-eight participants learned weakly associated Chinese word pairs via restudy(RS), retrieval practice with feedback (RP), and retrieval practice without feedback (NRP). After encoding, a nap group slept while a wake group remained awake. Recall was tested after 90 min and 24 h. Critically, only for NRP items did the nap group show significantly less forgetting (i.e., a reduced recall change rate) than the wake group. Furthermore, the NRP recall change rate correlated positively with sleep-specific neurophysiological markers (fast spindle density and fast spindle-ndPAC coupling). These findings demonstrate that initially labile memories formed by NRP undergo offline, sleep-dependent consolidation (involving neural replay indexed by spindles), integrated with online processes, to achieve long-term stability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The formation of memory representations encompasses three key stages: encoding, storage, and retrieval. It is crucial to acknowledge that these stages are not discrete and independent entities; rather, they function as a dynamic and intricately interconnected system1. Retrieval practice, a robust and widely recognized mnemonic strategy, plays a pivotal role in promoting learning through the very act of retrieval itself. This underscores the notion that retrieval serves not only as a recall process but also as an encoding mechanism for subsequent experiences2. Specifically, the retrieval practice effect refers to the empirically demonstrated phenomenon wherein memory retrieval, whether implemented once or repeatedly within a given study period, mitigates or even reverses time-dependent forgetting, ultimately yielding superior long-term memory retention compared to restudy3. For example, for short test intervals (e.g., 5 min), restudy yields better recall than retrieval practice; however, for longer intervals (e.g., 2 days or 1 week), retrieval practice leads to superior recall compared to restudy4,5. Consequently, the benefits of retrieval practice are primarily manifested during delayed testing, subsequent to the initial storage phase. During this offline period, memories that have been reinforced through retrieval practice undergo dynamic modifications prior to their stabilization as enduring, long-term representations.

Leading theoretical frameworks posit sleep as a preferential consolidator of weakly encoded memories. The Synaptic Homeostasis Hypothesis proposes that sleep-mediated synaptic downscaling selectively preserves salient connections while pruning inefficient ones6. Weakly encoded traces—vulnerable yet behaviorally relevant—may thus be disproportionately strengthened during this global synaptic renormalization7. Complementarily, Systems Consolidation Theory suggests sleep-dependent hippocampal-neocortical dialogue, facilitated by slow oscillations and spindles, actively reinforces fragile memories that lack cortical integration during wakefulness8. Rodent studies further support this framework: experiences with stronger initial encoding exhibit reduced neural replay during sleep9,10, implying sleep preferentially targets suboptimally formed traces.

Here, we interrogate how retrieval conditions modulate encoding strength and subsequent sleep consolidation. Feedback during retrieval practice provides immediate error correction, potentiating hippocampal reactivation and online consolidation—effectively creating “stronger” initial traces. In contrast, feedback-free retrieval lacks such reinforcement, resulting in weaker encoding that may render memories more dependent on offline sleep processes. This dichotomy aligns with neural replay mechanisms: MEG studies reveal rapid hippocampal reactivations during human episodic retrieval11 with feedback shown may amplify post-retrieval reactivation. Thus, memories formed without feedback may inherently possess greater susceptibility to sleep-dependent reprocessing due to their suboptimal initial encoding.

However, prior behavioral research indicates that the benefits of retrieval practice may be attenuated or even negated by sleep when corrective feedback is absent, or when the retention interval is less than 24 h12,13. The study employs a bifurcation model to explain that memory retrieval follows a normal distribution based on retrieval intensity, with items learned repetitively exhibiting lower retrieval intensity compared to successfully retrieved items14. Consequently, because successfully retrieved items already possess a high degree of memory strength, they are not preferentially targeted for reactivation during subsequent sleep periods, thereby preventing further consolidation. In contrast to these findings, Schoch et al. reported that immediate retrieval practice following emotional picture learning led to enhanced memory strength. Comparing delayed test performance between sleep and wake groups, they observed that sleep facilitated the consolidation of pictures with enhanced memory strength resulting from retrieval practice15. The apparent discrepancy with Bäuml’s findings may stem from differences in initial memory strength levels. Specifically, in Schoch’s study, retrieval practice increased memory strength from 11–24% to 20–38%, whereas in Bäuml et al.’s study, retrieval practice elevated memory strength from 75% to nearly 90%13. Indeed, accumulating evidence suggests that robust sleep-dependent consolidation effects are typically observed only when memory strength is at a moderate level (e.g., ~60% correct prior to retention), while highly encoded memories (pre-sleep performance exceeding 90% accuracy) may not derive substantial benefit from sleep consolidation7,16. Further research has demonstrated that a sleep group exhibits superior memory retention for items tested immediately after learning compared to a wake group, but no significant difference emerges after a two-hour delay17. However, the absence of a re-learning control group in that particular study limits the generalizability of its findings.

Furthermore, prior investigations have predominantly relied on behavioral measures, with limited direct evidence elucidating the neural mechanisms underlying the transformation of retrieval practice-induced memories during sleep. A substantial body of literature suggests that sleep spindles and slow oscillations play a critical role in memory consolidation processes. Sleep spindles, defined as oscillatory bursts occurring at 11–16 Hz during non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep, are considered pivotal for sleep-dependent brain plasticity and memory consolidation, processes facilitated by the brain’s periodic synchronous rhythms18,19. Empirical evidence indicates that memory reactivation during NREM sleep leads to a transient increase in spindle activity, enabling the accurate decoding of reactivated memory content20. From the perspective of synaptic plasticity, sleep spindles are associated with rhythmic, synchronous activity between presynaptic and postsynaptic neurons, thereby triggering the activation of calcium-dependent signaling cascades. This activation is crucial for the development of associative memories, which are fundamental for long-term synaptic plasticity21. Spindles are further differentiated into fast and slow subtypes, with the density of fast spindles exhibiting a strong positive correlation with the effectiveness of sleep in promoting memory consolidation22,23. It has been proposed that reorganization associated with fast spindles enhances functional connectivity within the hippocampal-cortical network and remodels memory representations in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC). This process supports sustained changes in memory organization both within and across brain regions, thus contributing to enhanced memory retention24. Moreover, slow oscillations, observed in human electroencephalograms with a peak frequency of ~0.75 Hz and primarily originating in the neocortical network, stimulate spindle activity through cortico-thalamic transmission. This activity subsequently propagates from the thalamus to the neocortex25,26. The synchronization of spindle activity with the upstate (peaks) of slow oscillations maximizes the beneficial impact of sleep-mediated memory consolidation27.

Given the lack of conclusive evidence regarding the dependency of sleep-dependent consolidation on memory strength in retrieval practice, we conducted exploratory analyses to examine potential mechanisms underlying this relationship. In the present study, we employed a between-subjects design, assigning participants to either a nap group or a wakefulness group. Participants engaged in the learning of word pairs using three distinct strategies—restudy, retrieval practice with feedback, and retrieval practice without feedback—to induce varying degrees of memory strength. Subsequently, we compared the two groups to evaluate differences in both immediate and delayed recall performance. The inclusion of a nap condition was dictated by the experimental protocol, which required participants to arrive at the laboratory at 11:00 AM on four consecutive days, each day utilizing a different learning strategy to study Chinese word pairs. Specifically, half of the participants underwent polysomnographic (PSG) monitoring during a 90 min nap following the learning phase, while the remaining participants remained awake for an equivalent duration. Both groups completed an immediate recall test after 90 min and a delayed recall test the following day upon returning to the laboratory. Weakly associated word pairs were selected as memory stimuli to maintain consistent task difficulty across experimental conditions and to minimize the influence of pre-existing semantic associations. Furthermore, PSG monitoring of the nap group enabled the extraction of electroencephalographic (EEG) features during sleep, thereby facilitating an investigation into the neurophysiological mechanisms through which sleep may modulate retrieval practice effects.

Results

Behavioral results

Firstly, the accuracy of recall was analyzed. A repeated measures ANOVA was conducted concerning 2 (Nap status: nap, wake) × 3 (Learning condition: restudy, retrieval practice without feedback, retrieval practice with feedback) × 2 (Test timing: immediate, delayed). Here, learning condition and test timing were within-subject variables, while nap status was a between-subjects variable. The dependent variable was the word pair recall rate in the immediate and delayed tests. Recall accuracy under various experimental conditions is presented in Table 1. The results showed a significant main effect of learning condition [F(2,92) = 125.27, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.73]. Further simple effect analysis revealed that the retrieval practice with feedback group significantly outperformed both the restudy and retrieval practice without feedback groups (p < 0.001), and the restudy group significantly outperformed the no-feedback group (p = 0.001). This indicates different memory strengths under the three learning conditions. The main effect of test timing was significant [F(1,46) = 486.30, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.91]. Further simple effect analysis revealed that the immediate test group significantly outperformed the delayed test group (p < 0.001).

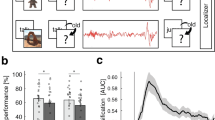

The interaction between learning condition and nap status was significant [F(2,92) = 10.00, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.18]. Further simple effect analyses revealed that in the immediate test condition, only under the retrieval practice without feedback condition did the nap group significantly outperform the wake group (p < 0.05); in the delayed test condition, similarly, only under the retrieval practice without feedback condition did the nap group significantly outperform the wake group (p < 0.001). In contrast, under restudy and retrieval practice with feedback conditions, there were no significant differences between the nap and wake groups in either immediate or delayed tests (p > 0.05). This indicates that nap only consolidates word pair memory under retrieval practice without feedback conditions. The interaction between the learning condition and test timing was significant [F(2,92) = 103.14, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.69]. Further simple effect analysis showed that under the immediate condition, the order of test scores from low to high was: retrieval practice without feedback group < restudy group < retrieval practice with feedback group (p < 0.001)(Fig. 1a); under the delayed condition, the order was the same: retrieval practice without feedback group < restudy group < retrieval practice with feedback group (p < 0.05) (Fig. 1b).

a Recall rate of word pairs during the immediate test for both the nap and wake groups. b Recall rate during the delayed test for both the nap and wake groups. c The change rate of word pairs under the three learning conditions for both groups of participants. d The difference in change in recall across the three learning conditions between the nap and wake groups.(Dots: Represent raw observations from individual participants; Error bars: Indicate ±1 standard error of the mean (SEM); Asterisks: p < 0.05, p < 0.01). NRP Retrieval practice without feedback, RS Restudy, RP Retrieval practice with feedback. The nap group is represented by Air Force blue, while the wake group is depicted in sky blue.

Furthermore, referring to the recall change rate formula by Denis7. Recall change rate = (delayed test − immediate test)/immediate test × 100%, we calculated the recall change rates under three learning conditions for both nap and wake groups. A repeated measures ANOVA with nap status (nap, wake) × learning condition (restudy, retrieval practice without feedback, retrieval practice with feedback) was conducted, where learning condition was a within-subject variable, nap status was a between-subjects variable, and the dependent variable was the word pair recall change rate. The results showed a significant main effect of learning condition [F(2,92) = 186.03, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.80] (Fig. 1c). Further simple effect analysis indicated that the recall change rate for the retrieval practice with feedback group was significantly lower than that for the restudy and retrieval practice without feedback groups (p < 0.001), with no significant difference between the restudy and retrieval practice without feedback groups (p > 0.05). There was a significant interaction between learning condition and nap status [F(2,92) = 9.30, p < 0.001, ηp2 = 0.17]. Further simple effect analysis revealed that only under the retrieval practice without feedback condition were there significant differences in word pair recall change rates between the nap and wake groups (p < 0.001), with the nap group showing lower rates than the wake group; there were no significant differences under the other two learning conditions.

To further investigate the underlying causes of these results, specifically whether they are attributable to napping or the type of learning, we first computed the differences in recall change for the three learning types (NRP-RP, NRP-RS, and RP-RS) between the nap and wake groups. A repeated measures ANOVA was then conducted to compare the recall change differences between the nap and wake groups for each learning type. The results revealed a significant main effect of these differences, F(2, 45) = 219.36, p < 0.001, η² = 0.90, with NRP-RP significantly higher than NRP-RS, and NRP-RS significantly higher than RP-RS. Additionally, the interaction between the differences and group was significant, F(2,45) = 6.77, p < 0.01, η² = 0.23. Further simple effects analysis showed that the NRP-RP value for the wake group was significantly higher than that for the nap group (p < 0.001), and the NRP-RS value for the wake group was also significantly higher than that for the nap group (p < 0.01). However, no significant difference was found in RP-RS values between the two groups (p > 0.05) (Fig. 1d). These findings suggest that the wake group exhibited greater differences in recall change, indicating that, in the absence of napping, the gap between retrieval practice with and without feedback, or restudy, was more pronounced. This may imply that participants who engage in retrieval practice without feedback, without rest, experience greater difficulty in achieving effective memory retention.

Sleep architecture and sleep stage correlations

Sleep statistics are presented in Table 2. There were no significant correlations between change in memory (for either all items or any of the three encoding strengths) and time or percentage of the nap spent in any sleep stage (all p values > 0.10). Complete analytical results are provided in Supplementary Table 2 to ensure full transparency.

Changes in spindle features

To examine whether the differences in spindle densities under different conditions were related to memory performance, we calculated the correlations between the densities of fast spindles, slow spindles, and the recall change rate under each learning condition. The results showed that only under the retrieval practice without feedback condition did the density of fast spindles at the frontal F3, central C3, and C4 electrode sites show a significant positive correlation with the recall change rate (Fig. 2 shows the correlation between the density of fast spindles and the recall change rate at the C3 electrode site. Correlation plots for fast spindle density and recall change rate at other electrode sites can be found in the Supplementary Fig. 1).

Correlation between fast spindle density, slow spindle density, and word pair recall rate at the C3 electrode site. (word pair recall rate in the retrieval practice without feedback condition; shade indicates 95% confidential interval). In this figure, red is used to represent slow spindles, while blue indicates fast spindles.

Previous studies have indicated significant variations in spindle wave activity among individuals with excessive sleepiness or insomnia, as well as across different individuals28. Although participants were instructed to maintain a regular sleep schedule for 2 weeks prior to the study, ESS values could still influence both memory performance and sleep EEG. To account for this potential confounding effect, ESS values were included in the partial correlation analysis. This allowed us to isolate the independent relationship between spindle wave density and recall change rate.

The results indicated that only under the retrieval practice without feedback condition did the fast spindle density at the frontal site F3 and the parietal sites C3 and C4 show a significant positive correlation with the recall change rate (Table 3). This suggests that after controlling for ESS values, the relationship between fast spindle density and memory consolidation remains significant. No significant correlations were observed between either fast or slow spindle density and the recall change rate under other conditions. These findings underscore that fast spindle density is primarily associated with memory consolidation during the retrieval practice without feedback condition.

Slow oscillation-spindle coupling

Both fast and slow spindles showed significant Rayleigh tests of nonuniformity across all electrode sites (all padj < 0.001), indicating that the coupling between fast spindles and slow oscillations, as well as the coupling between slow spindles and slow oscillations, exhibits nonuniformity. Subsequently, we examined the relationship between the coupling of fast spindles with slow oscillations and changes in recall during the delay period, as well as the correlation between slow spindle-slow oscillation coupling and recall change rate under different learning conditions. The results showed that only under the retrieval practice without feedback condition, at the frontal site F4 and the parietal sites C3 and C4, the coupled fast spindle ndPAC was positively correlated with the recall change rate (Fig. 3 shows the coupled fast spindle ndPAC, coupled slow spindle ndPAC, and word pair recall rate at the C3 electrode site. Correlation plots for coupled fast spindle ndPAC and recall change rate at other electrode sites can be found in the Supplementary Fig. 2).

a Correlation between coupled fast spindle ndPAC, coupled slow spindle ndPAC, and word pair recall rate at the C3 electrode site. b Schematic of the coupling between slow oscillations and spindles: Fast spindles synchronize with the rising phase of slow oscillations, while slow spindles synchronize with the descending phase. (word pair recall rate in the retrieval practice without feedback condition; shade indicate 95% confidential interval). In this figure, red is used to represent slow spindles, while blue indicates fast spindles.

Similarly, to control for the potential effects of individual differences, we included each participant’s ESS value in the model during partial correlation analysis. The results indicated that, under the retrieval practice without feedback condition, the coupled fast spindle ndPAC at the frontal site F4 and parietal sites C3 and C4 remained positively correlated with recall change (Table 4). However, no significant correlations were observed between the coupled slow spindle ndPAC and recall change in other conditions.

Discussion

In this study, we analyzed memory retention of word pairs in nap and wake groups under three different learning conditions: restudy, retrieval practice with feedback, and retrieval practice without feedback. Memory performance was evaluated through immediate and delayed tests conducted after 90 min and 24 h, respectively. Additionally, we investigated the electrophysiological characteristics exhibited under these conditions to examine whether the effect of retrieval practice is influenced by sleep consolidation and to uncover its underlying mechanisms.

Concerning the first question, the behavioral results revealed that, regardless of whether participants napped, recall rates were highest for retrieval practice with feedback, followed by restudy, the retrieval practice without feedback yielding the lowest recall rates. These findings are consistent with previous research, which demonstrated that retrieval practice with feedback significantly enhances recall compared to both restudy and retrieval practice without feedback within a short time frame. The lowest recall rates observed in retrieval practice without feedback condition are likely due to fewer encoding opportunities relative to restudy, resulting in weakly encoded words that were not successfully retrieved during subsequent tests, compounded by the absence of corrective feedback12. In the immediate test conducted after a 90 min interval, recall rates were significantly higher in the nap group compared to the wake group only in the retrieval practice without feedback condition. No significant differences were observed between nap and wake groups in restudy and feedback retrieval conditions. This suggests that offline consolidation during sleep enhanced memory for word pairs learned through retrieval practice without feedback. After 24 h, when comparing the forgetting rates across the three learning conditions, we found that nap groups showed significantly lower forgetting rates only under the retrieval practice without feedback condition. No significant difference in forgetting rates was found between nap and wake groups in the other two conditions, indicating that memories associated with retrieval practice without feedback were consolidated during the offline sleep period.

The second question concerns the electrophysiological correlates of memory consolidation during sleep. We first examined the relationship between sleep spindles and memory consolidation. We found that sleep spindles in EEG signals were associated with memory consolidation for retrieval practice without feedback, and this association was dependent on the type of spindle. Specifically, higher density of fast spindles was correlated with reduced forgetting in retrieval practice without feedback condition, whereas slow spindles were not associated with consolidation in any memory category. These results align with previous research indicating that only the number and density of fast spindles are positively correlated with consolidation in procedural memory7. Additionally, we calculated the coupling density and strength (ndPAC) between spindles and slow oscillations, exploring their relationship with memory consolidation under the three learning conditions. Contrary to previous studies, we did not observe a correlation between spindle-slow oscillation coupling density and memory consolidation. However, we did find that, under the non-feedback condition, the coupling strength between fast spindles and slow oscillations was associated with changes in recall rates, a correlation not observed in restudy or feedback conditions. Previous studies have highlighted the importance of coupling between cortical and subcortical oscillations, with slow oscillation-spindle coupling facilitating the reactivation of memory traces in the hippocampus, thereby enhancing memory consolidation in the hippocampus-neocortex loop. The degree of coupling is associated with sleep-based consolidation7.

Based on these findings, we posit that memory traces formed through feedback-free retrieval practice undergo reactivation during subsequent sleep, thereby facilitating memory consolidation. Under feedback-free conditions, successfully retrieved items do not receive strong encoding after initial retrieval (encoded only once). Compared to restudy or feedback-based retrieval tasks, these items exhibit weaker memory strength and form only conceptually-related semantic memory networks. During subsequent offline periods (i.e., sleep), these memory traces and their associated semantic networks are repeatedly reactivated and replayed, gradually enhancing memory strength. Conversely, restudy tasks do not trigger replay during offline periods due to the absence of relevant semantic networks formed during online learning.

These mechanisms align with the core tenets of the Complementary Learning Systems (CLS) theoretical framework, which posits that sleep enhances memory stability and persistence through post-retrieval integration and consolidation of semantic networks29. This consolidation process is critically mediated by the activation of semantic networks. Empirical studies on sleep-dependent consolidation of associative memories reveal that, compared to wake control groups, participants experiencing overnight sleep demonstrate superior retention not only for directly learned associations (e.g., A-B and B-C face-object pairs) but also exhibit advantages in relational memory inference (A-C face-face pairs)30. Nap studies likewise confirm that sleep concurrently facilitates consolidation of both direct associative memories and relational memories31. The neural implementation involves a three-stage processing cascade: 1) Wakeful memory replay strengthens synaptic weights between associative tasks; 2) Relational memory depends on multi-item representational overlap, with sleep spindles facilitating targeted reinforcement of cross-item connections; 3) When online cue saliency is insufficient, slow oscillations initiate compensatory network reorganization. Animal electrophysiology evidence shows significantly increased neural replay frequency post-no-feedback learning, with replay sequences highly congruent with memory retrieval paths, confirming offline reorganization directly remediates encoding deficits32.

We propose a dual-phase consolidation model for retrieval-practiced memories, wherein memory strength within this dichotomous framework develops progressively through offline processes. For no-feedback tasks, the absence of explicit error signals during encoding necessitates sleep-dependent systematic replay for successful memory integration. Conversely, feedback-based tasks achieve immediate pathway correction via online monitoring mechanisms without requiring offline reprocessing. Thus, sleep-mediated replay and synaptic renormalization constitute the core drivers of this dynamic consolidation process in the proposed framework.

Furthermore, theoretical hypotheses on retrieval practice primarily include the elaborative retrieval hypothesis and the contextual background hypothesis. The elaborative retrieval hypothesis suggests that when participants use retrieval cues to search for target items, it activates semantically related information in memory, which is then finely encoded. These finely processed semantic associations serve as more effective retrieval cues during the final test, thereby facilitating memory33,34. The Contextual Background Hypothesis posits that individuals encode not only the event itself but also the context in which the event occurred. Both the event and its corresponding context are stored in memory35. During retrieval, participants use available cues to reconstruct the background of the event. If the current background has significantly changed, participants will reconstruct the original context and use this reconstructed background to guide their search. If items from the past learning context are successfully retrieved in the current context, the background representation of those items will be updated, combining elements of both the old and new backgrounds. During the final test, participants reconstruct the background again, and the updated background representation serves as an effective retrieval cue, guiding them to the target item36. We contend that, apart from the online encoding and retrieval processes, retrieval practice involves mechanisms distinct from those of relearning. The offline consolidation phase also plays an essential role in the effects of retrieval practice. The retrieval practice effect is likely the result of a combination of fine encoding during the encoding phase, semantic network reactivation during the offline phase, and background cue reconstruction during the retrieval phase. This suggests that for learners, using retrieval practice before sleep yields superior memory outcomes compared to retrieval practice followed by a longer period of wakefulness.

While this study advances our understanding of sleep-dependent memory consolidation, several limitations merit consideration. First, Critically, although no statistically significant associations were found after multiple comparison correction, exploratory analysis revealed two moderate-magnitude correlations: central fast spindle density (mean of C3 and C4 electrodes) showed significant correlation with memory retention following retrieval practice without feedback (r = 0.519, p(FDR-corrected) = 0.033); simultaneously, central fast spindle-slow oscillation coupling strength (ndPAC) (mean of C3 and C4 electrodes) also demonstrated significant correlation with memory retention after feedback-free retrieval practice (r = 0.514, p(FDR-corrected)=0.036)—a pattern not observed in restudy or feedback-based retrieval conditions. While limited by statistical power, these condition- and region-specific effects align with active system consolidation theory, suggesting spindles may preferentially support memories reliant on endogenous retrieval processes. In addition, while this study provides evidence regarding the influence of slow wave-spindle coupling on weakly encoded memories, it should be acknowledged that the correlational design precludes definitive causal inferences regarding its role in memory.

We did not identify any specific association patterns between the duration or proportion of particular sleep stages and memory performance. This observation may be attributed to several factors: First, current research suggests that microscopic neural oscillation characteristics (such as spindle density and slow-wave amplitude) may serve as more effective predictors of memory consolidation effects compared to macroscopic sleep stage duration or architecture. Second, the sensitivity to sleep stages may vary across different types of memory tasks, representing a potential domain-specific difference that could explain the negative findings in our study. We recommend that future investigations incorporate multidimensional sleep indicators to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the complex relationship between sleep and memory consolidation.

Notably, the current study observed higher immediate recall accuracy in the nap group compared to the wake group under the retrieval practice without feedback condition. This baseline difference may potentially influence the interpretation of sleep-dependent consolidation effects. Although our sample size was determined through a priori power analysis and aligns with comparable sleep studies7, the inherent variability in sleep electrophysiology may benefit from larger samples in future replications to better characterize individual differences. Furthermore, while our wake condition employed carefully curated low-demand activities to minimize active rehearsal and avoid biases inherent to pure rest or single-activity paradigms, we recognize that individual differences in cognitive engagement levels may still exist.

In addition, an alternative explanation for the null effects in the feedback and restudy conditions could relate to differences in initial encoding strength: Feedback, by providing corrective information, may strengthen memory traces during the encoding phase, rendering them less dependent on subsequent sleep-related consolidation. Similarly, restudy trials inherently involve repeated exposure, which could also lead to more robust initial encoding. Future studies could explicitly manipulate encoding strength to test this hypothesis.

To conclude, our study highlights the crucial role of sleep in memory consolidation following retrieval practice without feedback. Our results demonstrate that offline consolidation during nap periods enhances memory retention, with the reactivation of memory traces during sleep, as reflected in behavioral and electrophysiological measures. Fast sleep spindles were associated with reduced forgetting, suggesting that specific neural mechanisms facilitate consolidation. These findings support the Complementary Learning Systems model, indicating that sleep aids in the integration and stabilization of memory networks. However, further research with full-night sleep assessments and longer follow-up periods is needed to deepen our understanding of how sleep stages contribute to long-term memory stabilization following retrieval practice.

Methods

Participants

This study recruited 52 undergraduate students from Northwest Normal University (27 females, average age of 22 years, SD = 2.6). Four participants were excluded due to incomplete participation in the experiment; the final sample consisted of 48 participants (24 per condition: nap vs. wake). Nap group: 13 females, mean age 22.1 ± 1.0 years;Wake group: 13 females, mean age 22.1 ± 0.95 years. An a priori power analysis was conducted using GPower 3.1.9.7 with α = 0.05, power = 0.80, and a medium effect size (Cohen’s f = 0.35). This analysis determined a minimum requirement of 42 participants. The final cohort of 48 participants provided robust sensitivity, with post hoc power exceeding 0.83 for effect sizes of f ≥ 0.30. All subjects had normal or corrected-to-normal vision, were right-handed, had no psychiatric disorders, no history of alcohol or drug abuse, no history of psychiatric illness, sleep disorders, or brain injuries, and had not taken any medications affecting sleep or cognition recently. Participants were required to maintain regular sleep habits for two weeks before the experiment (≥7 h of sleep per night, bedtime between 11 PM and 1 AM, waking time between 6 AM and 8 AM), and avoid intake of alcoholic beverages, caffeine, and tea during the study period. All participants completed three questionnaires as part of the inclusion criteria: the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index37 (PSQI; ≤ 7), the Stanford Sleepiness Scale38 (SSS; < 9), Epworth Sleepiness Scale39 (ESS; < 7). All subjects signed an informed consent form before participating in the experiment and received corresponding compensation upon completion. This study was approved by the local ethics committee. Before participation, all subjects gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the School of Psychology, Northwest Normal University (Approval No. 2023087).

Materials

This study employed paired associative word pairs as learning materials, adapting and translating the English nouns from the experiment conducted by Carpenter (2009). The strong and weak cue words were obtained based on the standards set by Nelson et al. 40. Initially, word pairs with an average probability of recalling the target word from the cue word at 0.33 were defined as strong cue pairs, and those with an average recall probability of 0.01 were defined as weak cue pairs. Both strong and weak cue pairs were translated into Chinese two-character word pairs. Secondly, to changes in the strength of semantic relationships due to cultural differences, 30 university students were asked to rate the relevance of the selected word pairs on a Likert five-point scale before the formal experiment. Results indicated that strong cue words (M = 3.77) were significantly more relevant than weak cue words (M = 3.14), t (179) = 14.5, p < 0.001. For example, the target word “英亩” shows a strong association with the cue word “土地”(probability = 0.675), but only a weak association with “财产” (probability = 0.016). None of these students participated in the formal experiment. Since this study only used weak cue pairs as learning material, 96 pairs were randomly selected from the weak cue pairs and randomly assigned to three conditions: restudy, retrieval practice with feedback, and retrieval practice without feedback, with each condition containing pairs. In each word pair, the first word served as the cue, and the second as the target. Refer to Supplementary Table 3 for the exhaustive list of word pairs.

Experimental design

The experimental design is illustrated in Fig. 4a, where participants were randomly assigned to either a nap or wake group. A Latin square design was used to balance the order of the three learning strategies: restudy, retrieval practice with feedback, and retrieval practice without feedback. Participants were not informed of their learning strategy before arriving at the sleep laboratory each day. On the first day of the experiment, participants were asked to arrive at the laboratory by 12:00 PM. They initially completed the first learning session of pairs on a computer, with each pair presented for 3000 ms followed by a 500 ms inter-stimulus interval for the next pair (Fig. 4b). After a 10 min break following the initial learning session, participants engaged in one of the three learning strategies again, according to the instructions displayed on the screen. In the restudy condition, each word pair was presented for 8000 ms; under retrieval practice with feedback, the cue word was first presented for 5000 ms, and participants were asked to verbally report the corresponding target word, with the target word provided in the final 3000 ms; under the retrieval practice without feedback condition, only the cue word was shown for 8000 ms, and participants were asked to verbally report the corresponding target word. The interval between word pairs was 500 ms for all three conditions. After completing both learning sessions, the nap group underwent polysomnographic (PSG) monitoring and began nap from 1:00 PM to 3:00 PM, while participants in the wake group were engaged in playing mobile games or chatting with the experimenter during the same period, avoiding quiet rest or nap41. Subsequently, both groups underwent an immediate test and a delayed test the following day at 10:30 AM for the word pairs learned the previous day. The testing method at both points was the same, only presenting the cue word for 8000 ms, and participants were asked to recall and write down the corresponding target word on an answer sheet (Fig. 4b). After completing the delayed test, participants had lunch. At 12:00 PM, another set of pairs was learned, followed by restudy using the prompted strategy after a ten-minute break, similar to the first day. The procedure for the third day was the same as the second day, except for different learning strategies and corresponding word pairs. The fourth day involved the delayed test for the pairs learned on the third day.

a On Day 1, participants learned word pairs at 12:00 PM. After a second learning session using one of three strategies, the nap group napped (1:00–3:00 PM) under PSG monitoring while the wake group remained awake. Both took an immediate test post-session. On Day 2, delayed tests occurred at 10:30 AM. New pairs were learned at 12:00 PM using another strategy, followed by identical procedures as Day 1. Day 3 replicated Day 2. On Day 4, delayed tests were administered for Day 3’s 32-word pairs. b During the initial learning, each word pair was presented for 3000 ms, followed by a 500 ms interval before the next pair. During testing, each word pair was presented for 8000 ms, followed by a 500 ms interval before the next pair. The nap group is represented by Air Force blue, while the wake group is depicted in sky blue.

EEG acquisition and preprocessing

Sleep monitoring was conducted using the Compumedics E-Series 32-channel PSG system (Compumedics Sleep Study System, Melbourne, Australia). Based on the international 10-20 electrode placement system, EEG scalp electrodes were attached at frontal (F3, F4), central (C3, C4), and occipital (O1, O2) regions, with each site referenced to the contralateral mastoid (A1 or A2). Electrooculography (EOG) and submental electromyography (EMG) electrodes were also placed to record eye movements and muscle tone, respectively. The sampling rate was set to 500 Hz, with EEG electrode impedance below 5 kΩ and EOG and EMG electrode impedance below 10 kΩ. High-pass filtering was set to 35 Hz and low-pass filtering to 0.3 Hz. All recorded data underwent rigorous artifact screening procedures conducted by trained experimenters, who visually identified and subsequently excluded physiological artifacts from further analysis. Due to the inherent constraints of our low-density EEG setup (6 recording channels), we implemented a conservative approach for handling contaminated channels: Rather than performing channel interpolation which could introduce biases in sparse-array configurations, irreparably artifact-laden channels were systematically excluded prior to bandpass filtering. Sleep staging was performed by two professional sleep technicians according to the rules established by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events, version 2.6, for the stages N1, N2, N3, and REM. Data from all EEG channels during the NREM sleep stages (N1, N2, and N3) were extracted for spindle and slow oscillation analysis. Data analysis was conducted offline using EEGLAB in Matlab (R2013b), with EEG data downsampled to 200 Hz. The electrode order was adjusted, arranging all electrodes in the sequence ‘F3’, ‘F4’, ‘C3’, ‘C4’, ‘O1’, and ‘O2’.

Spindle detection

Spindle detection was performed using an automatic algorithm42. The frequency with the maximum amplitude was taken as the frequency of that spindle. If the spindle frequency was greater than 12.5 Hz, it was defined as a fast spindle; if the frequency was less than 12.5 Hz, it was defined as a slow spindle. Spindle density was calculated as the number of spindles per minute divided by time, computing both fast and slow spindle densities under the three learning conditions in the nap group. In addition, the amplitude and duration of all detected spindles during the NREM phase were also calculated. Spindle amplitude: The EEG data were band-pass filtered at 10–18 Hz, and the Hilbert transform was used to extract the signal envelope. The maximum amplitude within each spindle occurrence period was taken as the amplitude of that spindle. Spindle duration: The duration of each spindle was calculated from the start to the end of the spindle.

Detection of slow oscillations and slow oscillation-spindle coupling

Slow oscillation detection and slow oscillation-spindle coupling were conducted using the same methodology as described by Denis7. In addition, in this study, coupling strength was calculated using the normalized direct phase-amplitude coupling (ndPAC) method. The coupling strength was assessed as the mean vector length of these phase-amplitude couplings.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Code availability

Custom-written code is available upon request by contacting the corresponding author.

Change history

26 December 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41539-025-00393-4

References

Guskjolen, A. & Cembrowski, M. S. Engram neurons: encoding, consolidation, retrieval, and forgetting of memory. Mol. Psychiatry 28, 3207–3219 (2023).

McDermott, K. B. Practicing retrieval facilitates learning. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 72, 609–633 (2021).

Karpicke, J. D. Retrieval-based learning: a decade of progress. In Learning and Memory: A Comprehensive Reference 487–514 (Elsevier, 2017).

Roediger, H. L. & Karpicke, J. D. Test-enhanced learning: taking memory tests improves long-term retention. Psychol. Sci. 17, 249–255 (2006).

Roediger, H. L. & Karpicke, J. D. The power of testing memory: basic research and implications for educational practice. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 1, 181–210 (2006).

Tononi, G. & Cirelli, C. Sleep and the price of plasticity: from synaptic and cellular homeostasis to memory consolidation and integration. Neuron 81, 12–34 (2014).

Denis, D. et al. Sleep spindles preferentially consolidate weakly encoded memories. J. Neurosci. 41, 4088–4099 (2021).

Petzka, M., Charest, I., Balanos, G. M. & Staresina, B. P. Does sleep-dependent consolidation favour weak memories? Cortex 134, 65–75 (2021).

Johnson, A. & Redish, A. D. Neural ensembles in CA3 transiently encode paths forward of the animal at a decision point. J. Neurosci. 27, 12176–12189 (2007).

Singer, A. C., Carr, M. F., Karlsson, M. P. & Frank, L. M. Hippocampal SWR Activity Predicts Correct Decisions during the Initial Learning of an Alternation Task. Neuron 77, 1163–1173 (2013).

Mallory, C. S., Widloski, J. & Foster, D. J. The time course and organization of hippocampal replay. Science 387, 541–548 (2025).

Abel, M. et al. Sleep reduces the testing effect-But not after corrective feedback and prolonged retention interval. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn Mem. Cogn. 45, 272–287 (2019).

Bäuml, K.-H. T., Holterman, C. & Abel, M. Sleep can reduce the testing effect: It enhances recall of restudied items but can leave recall of retrieved items unaffected. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn., Mem. Cognit. 40, 1568–1581 (2014).

Kornell, N., Bjork, R. A. & Garcia, M. A. Why tests appear to prevent forgetting: a distribution-based bifurcation model. J. Mem. Lang. 65, 85–97 (2011).

Schoch, S. F., Cordi, M. J. & Rasch, B. Modulating influences of memory strength and sensitivity of the retrieval test on the detectability of the sleep consolidation effect. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 145, 181–189 (2017).

Denis, D. et al. The roles of item exposure and visualization success in the consolidation of memories across wake and sleep. Learn Mem. 27, 451–456 (2020).

Kroneisen, M. & Kuepper-Tetzel, C. E. Using day and night—scheduling retrieval practice and sleep. Psychol. Learn. Teach. 20, 40–57 (2020).

Antony, J. W., Ferreira, C. S., Norman, K. A. & Wimber, M. Retrieval as a fast route to memory consolidation. Trends Cogn. Sci. 21, 573–576 (2017).

Rasch, B. & Born, J. About sleep’s role in memory. Physiol. Rev. 93, 681–766 (2013).

Cairney, S. A., Guttesen, A.ÁV., El Marj, N. & Staresina, B. P. Memory consolidation is linked to spindle-mediated information processing during sleep. Curr. Biol. 28, 948–954.e944 (2018).

Fernandez, L. M. J. & Lüthi, A. Sleep spindles: mechanisms and functions. Physiol. Rev. 100, 805–868 (2020).

Cox, R., Hofman, W. F. & Talamini, L. M. Involvement of spindles in memory consolidation is slow wave sleep-specific. Learn. Mem. 19, 264–267 (2012).

Kumar, S. et al. Using natural language and program abstractions to instill human inductive biases in machines. In Proc. 36th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 167–180 (Curran Associates Inc., Red Hook, NY, USA, 2022).

Cowan, E. et al. Sleep spindles promote the restructuring of memory representations in ventromedial prefrontal cortex through enhanced hippocampal–cortical functional connectivity. J. Neurosci. 40, 1909–1919 (2020).

Mölle, M., Bergmann, T. O., Marshall, L. & Born, J. Fast and slow spindles during the sleep slow oscillation: disparate coalescence and engagement in memory processing. Sleep 34, 1411–1421 (2011).

Staresina, B. P. et al. Hierarchical nesting of slow oscillations, spindles and ripples in the human hippocampus during sleep. Nat. Neurosci. 18, 1679–1686 (2015).

Niknazar, H., Malerba, P. & Mednick, S. C. Slow oscillations promote long-range effective communication: the key for memory consolidation in a broken-down network. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2122515119 (2022).

Campbell, I. G., Zhang, Z. Y. & Grimm, K. J. Sleep restriction effects on sleep spindles in adolescents and relation of these effects to subsequent daytime sleepiness and cognition. SLEEP 46, zsad071 (2023).

Liu, X. L., Ranganath, C. & O’Reilly, R. C. A complementary learning systems model of how sleep moderates retrieval practice effects. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 31, 2022–2035 (2024).

Huguet, M., Payne, J. D., Kim, S. Y. & Alger, S. E. Overnight sleep benefits both neutral and negative direct associative and relational memory. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 19, 1391–1403 (2019).

Alger, S. E. & Payne, J. D. The differential effects of emotional salience on direct associative and relational memory during a nap. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 16, 1150–1163 (2016).

Aly, M. H., Abdou, K., Okubo-Suzuki, R., Nomoto, M. & Inokuchi, K. Selective engram coreactivation in idling brain inspires implicit learning. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2201578119 (2022).

Carpenter, S. K. Cue strength as a moderator of the testing effect: The benefits of elaborative retrieval. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 35, 1563–1569 (2009).

Rawson, K. A., Vaughn, K. E. & Carpenter, S. K. Does the benefit of testing depend on lag, and if so, why? Evaluating the elaborative retrieval hypothesis. Mem. Cogn. 43, 619–633 (2015).

Karpicke, J. D., Lehman, M. & Aue, W. R. Retrieval-based learning. In Psychology of Learning and Motivation. Vol. 61, 237–284 (Elsevier, 2014).

Whiffen, J. W. & Karpicke, J. D. The role of episodic context in retrieval practice effects. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 43, 1036–1046 (2017).

Guo, S., Sun, W., Liu, C. & Wu, S. Structural validity of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index in Chinese undergraduate students. Front. Psychol. 07, 1126 (2016).

Shahid, A., Wilkinson, K., Marcu, S. & Shapiro, C. M. Stanford Sleepiness Scale (SSS). In STOP, THAT and One Hundred Other Sleep Scales (eds Shahid, A., Wilkinson, K., Marcu, S. & Shapiro, C. M.) 369–370 (Springer New York, 2011).

Vivekanandhan, G. et al. Golabi et al. BMC Psychiatry 32, 2450100 (2024).

Nelson, D. L., McEvoy, C. L. & Schreiber, T. A. The University of South Florida free association, rhyme, and word fragment norms. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 36, 402–407 (2004).

Scullin, M. K., Fairley, J., Decker, M. J. & Bliwise, D. L. The effects of an afternoon nap on episodic memory in young and older adults. Sleep 40, zsx035 (2017).

Lacourse, K., Delfrate, J., Beaudry, J., Peppard, P. & Warby, S. C. A sleep spindle detection algorithm that emulates human expert spindle scoring. J. Neurosci. Methods 316, 3–11 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the following funding sources: the scientific and technological innovation 2030—the major project of the Brain Science and Brain-Inspired Intelligence Technology (2021ZD0200500), the Lanzhou Science and Technology Planning Project (Grant No. 2022-3-55), and the Clinical Medical Research Promotion Program (Grant No. 2025CMFA10). We also sincerely appreciate all the volunteers who participated in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.Z. contributed to the conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, writing—original draft, and visualization. J.X. and X.M. participated in the analysis, investigation, and writing—review and editing. X.H. and H.L. were involved in the analysis and investigation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, J., Huo, X., Lv, H. et al. Offline consolidation mechanisms of the retrieval practice effect: an analysis based on EEG signal characteristics. npj Sci. Learn. 10, 63 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41539-025-00349-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41539-025-00349-8