Abstract

The effect of mindfulness training on working memory is unclear. The current study sought to confirm the impact of mindfulness training on working memory for facial stimuli and to reveal the cognitive mechanisms underlying this effect by using drift-diffusion modeling (DDM). Using a delayed match-to-sample task with facial stimuli, we measured memory performance across five emotional categories (happy, sad, fearful, angry, neutral). Sixty participants received five-week emotion-targeted mindfulness training versus 60 waitlist controls. Assessments pre-training, post-training, and at one-month follow-up revealed significantly improved memory accuracy for all emotions except fear, with the effects persisting for one month. More importantly, drift-diffusion modeling showed increased drift rates across emotional categories post-training. Furthermore, accuracy improvements strongly correlated with drift rate enhancements within each emotion category. These findings demonstrate that mindfulness training induces lasting improvements in both accuracy and processing efficiency of visual working memory, independent of facial emotions, clarifying its cognitive mechanisms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mindfulness is a state characterized by bringing intentional awareness to present internal and external experiences with curiosity, openness, acceptance, and without judgment, free from entanglement in rumination about past experiences and anxieties about the future1,2. From this perspective, mindfulness fundamentally involves two core components: (1) intentionally directing attention to present experiences, and (2) adopting an accepting attitude toward these experiences. The human mind relies on a set of cognitive processes, such as attention and working memory, to guide its moment-to-moment experiences. However, when these processes become abnormal, it can lead to difficulties in coping with life’s challenges. Mindfulness training serves as a form of mental exercise that improves these fundamental cognitive processes3. Mindfulness training can enhance meta-awareness by consciously monitoring thoughts, emotions, and behaviors, which contribute to modifying maladaptively automatic cognitive patterns and disrupting maladaptively automatic reaction patterns to stimuli4,5,6. A large number of studies revealed that mindfulness training can alter a variety of cognitive processes, including various forms of perception7,8,9, attention10,11,12,13,14, and memory15,16,17.

Working memory plays a core role in cognitive processing, providing temporary storage and manipulation of the information necessary for cognitive tasks18. The efficacy of working memory can significantly influence one’s ability to process information, thereby impacting overall cognitive performance and daily functioning. Baddeley19 proposed that working memory comprises the central executive system, two subsidiary slave systems—the phonological loop and the visuospatial sketchpad, and the episodic buffer19. The central executive system, an attentional control system, is capable of retrieving information from storage in the form of conscious awareness. Holas and Jankowski propose a cognitive model of mindfulness that emphasizes the cognitive processes shaping a state of mindfulness, with the executive functions of attention and working memory components identified as their determinants20. However, previous findings regarding the effects of mindfulness training on working memory are mixed. Although a large number of studies have revealed that mindfulness training improves working memory21,22,23,24,25,26, some other studies did not find such an effect27,28,29,30. Therefore, it is necessary to examine the effect of mindfulness training on working memory processing, and related influencing factors. One of the possible factors that can influence working memory is emotion. The valence, arousal, and motivational dimensions of emotional content can all influence working memory performance31. It was found that emotional expressions facilitated working memory32. Evidence showed that the performance of working memory was lower for neutral and happy faces than for negative faces33,34. However, other studies have revealed that identity recognition accuracy is higher for happy faces than for angry faces in a 2-back face identity matching task35, and working memory performance is faster for happy than for neutral and sad faces36. Nevertheless, there is a study showing that task accuracy remains unaffected by the emotional content of the stimuli37. In a modified Recency-probes paradigm, both the valence and arousal of emotional stimuli facilitate interference resolution in working memory38. Furthermore, mindfulness training may be able to reduce emotional reactivity by fostering non-judgmental awareness. Previous studies have shown that mindfulness reduces emotional reactivity to emotional stimuli39,40,41,42. This dampening of emotional interference frees attentional resources, potentially enhancing working memory for both emotional and neutral content. To test whether emotion moderates mindfulness-related working memory improvements, we examined the impact of mindfulness training on working memory across five facial emotion categories (happy, sad, fearful, angry, neutral) using drift-diffusion modeling to disentangle cognitive efficiency from emotional bias in the present study. Given mindfulness training’s established role in reducing emotional reactivity, we further hypothesized that training-induced improvements would be emotion-independent. Specifically, mindfulness training would enhance the accuracy and processing efficiency of working memory across emotional categories.

Working memory can be assessed using the delayed match-to-sample (DMTS) task43,44,45,46, in which one or more stimuli are presented as a sample (encoding), and after a delay period (maintenance), the effectiveness of maintaining the sample information is assessed by presenting a test stimulus and requiring participants to indicate whether the test stimulus matches the sample (retrieval)45. Previous studies have indicated that the DMTS task exhibits stable test-retest scores47 and shares common underlying networks of working memory48. Our task followed a classic three-phase structure: (1) Encoding phase: Two sample faces (emotional or neutral) were presented for 1000 ms. (2) Delay phase: A 2000 ms blank interval to prevent sensory persistence. (3) Retrieval phase: A single test face was presented centrally, and participants indicated via key press whether it matched one of the sample faces.

Traditionally, cognitive processing was assessed by response accuracy and time. However, these behavioral indicators include components beyond cognition. The drift-diffusion model (DDM), a perceptual decision-making model, can separate different components from observed behavioral variables49,50. The DDM is widely applied to fit the evidence-accumulation process of various tasks51,52,53,54,55,56. It hypothesizes that individuals stochastically accumulate evidence from a starting point until reaching a decision boundary, triggering a choice. Fig. 1 characterizes the model and illustrates key parameters. Four model parameters are fitted. Drift rate (v) represents the average evidence accumulation speed. A higher v indicates a lower task difficulty or higher ability. Decision boundary (a) represents the difference between boundaries. Higher a increases accuracy but slows responses. Bias (z) represents the starting point of evidence accumulation. Nondecision time (t) represents the time not used for the process of decision-making (e.g., motor execution). Studies show training can alter DDM parameters, like increasing drift rates57 or decreasing boundary separation58. However, no comprehensive studies have specifically examined which DDM parameters mindfulness training affects. Given mindfulness’s characteristics, it is interesting to explore if it influences v (cognitive processing) or t (non-reacting). While mindfulness benefits working memory and cognitive control, the mechanisms are unclear. The DDM provides a robust framework for decomposing decision processes into distinct components. Results from the present study could significantly enhance understanding of how mindfulness impacts the working memory mechanism.

Results

All the results for each test phase are presented in the supplementary materials (Table S1, Table S2, Table S3).

Mindfulness

Immediately after training, the training group showed a significantly larger improvement in dispositional mindfulness than the control group (t(118) = 2.26, p = .026, Cohen’s d = 0.41, 95% CI [0.42, 0.41]). This effect persisted one month after training (t(118) = 2.39, p = 0.018, Cohen’s d = 0.44, 95% CI [0.50, 5.27]). The results indicate that the mindfulness training enhanced the level of mindfulness effectively.

Accuracy and RT

We first calculated the improvements in accuracies, RTs for the correct responses, and d’ immediately after training (T2-T1) and one month after training (T3-T1).

Regarding the T2-T1 improvements in accuracies, independent samples t test showed significantly larger improvements for the training group than the control group for the happy (t(118) = 2.79, p = 0.031, Cohen’s d = 0.51, 95% CI [0.01, 0.08], Bonferroni corrected), sad (t(118) = 4.05, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.74, 95% CI [0.03, 0.08], Bonferroni corrected), angry (t(118) = 3.13, p = 0.011, Cohen’s d = 0.57, 95% CI [0.02, 0.08], Bonferroni corrected), and neutral (t(118) = 2.89, p = 0.023, Cohen’s d = 0.53, 95% CI [0.01, 0.08], Bonferroni corrected) faces. However, the difference was nonsignificant for the fearful face (t(118) = 1.33, p = 0.187, Cohen’s d = 0.24, 95% CI [–0.01, 0.06], uncorrected).

Regarding the T3-T1 improvements in accuracies, independent samples t test showed significantly larger improvements for the training group than the control group for the happy (t(118) = 3.77, p = 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.69, 95% CI [0.03, 0.10], Bonferroni corrected), sad (t(118) = 3.16, p = 0.010, Cohen’s d = 0.58, 95% CI [0.02, .08], Bonferroni corrected), and neutral (t(118) = 2.89, p = 0.023, Cohen’s d = 0.53, 95% CI [0.02, 0.09], Bonferroni corrected) faces. The difference was marginally significant for the angry face (t(118) = 2.20, p = 0.030, Cohen’s d = 0.40, 95% CI [0.003, 0.07], uncorrected) and nonsignificant for the fearful face (t(118) = 1.73, p = 0.087, Cohen’s d = 0.32, 95% CI [–0.004, 0.06], uncorrected). The results for the improvements in accuracies are presented in Fig. 2.

Regarding the RTs, no significant difference was found between groups for T2-T1 improvements (all t < 2.2, p > 0.05, Bonferroni corrected), as well as T3-T1 improvements (all t < 1.1, p > 0.05, Bonferroni corrected).

Besides, we also calculated the d’ for the DMTS task according to the Signal Detection Theory. The descriptive statistics and between-group difference for d’ were reported in Table S1 and Table S3. In summary, the training group showed significantly larger improvements in sad and angry faces at T2 (both t > 2.8, p < 0.05, Bonferroni corrected), and in sad and happy faces at T3 (both t > 3.1, p < 0.05, Bonferroni corrected).

Modeling parameters

Four parameters, including drift rate (v), decision boundary (a), initial bias (z), and nondecision time (t), were extracted. Improvements in these parameters were calculated immediately after training (T2-T1) and one month after training (T3-T1).

Drift rate is the core parameter in DDM, which reflects the cognitive processing of evidence accumulation. The results of improvements in v are presented in Fig. 3.

Regarding the T2-T1 improvements in v, independent samples ttest showed significantly larger improvements for the training group than the control group for the happy (t(118) = 3.05, p = 0.014, Cohen’s d = 0.56, 95% CI [0.06, 0.26], Bonferroni corrected), sad (t(118) = 4.32, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.79, 95% CI [0.13, 0.35], Bonferroni corrected), and angry (t(118) = 3.12, p = 0.011, Cohen’s d = 0.57, 95% CI [0.07, 0.30], Bonferroni corrected) faces. The difference was marginally significant for the neutral face (t(118) = 2.60, p = 0.010, Cohen’s d = 0.48, 95% CI [0.03, 0.22], uncorrected) and nonsignificant for the fearful face (t(118) = 1.97, p = 0.051, Cohen’s d = 0.36, 95% CI [–0.0003, 0.25], uncorrected).

Regarding the T3-T1 improvements, independent samples t test showed significantly larger improvements for the training group than the control group for the happy (t(118) = 3.48, p = 0.004, Cohen’s d = 0.64, 95% CI [0.12, 0.43], Bonferroni corrected) and sad (t(118) = 3.04, p = 0.015, Cohen’s d = 0.55, 95% CI [0.09, 0.45], Bonferroni corrected) faces. The difference was marginally significant for angry (t(118) = 2.06, p = 0.042, Cohen’s d = 0.38, 95% CI [0.01, 0.37], uncorrected), fearful (t(118) = 2.09, p = 0.039, Cohen’s d = 0.38, 95% CI [0.01, 0.36], uncorrected), and neutral (t(118) = 2.13, p = 0.035, Cohen’s d = 0.39, 95% CI [0.01, 0.28], uncorrected) faces.

Similarly, we compared the group difference in the improvements in other parameters. At T2, the training group showed larger improvements in t for fearful (t(118) = 3.10, p = 0.012, Cohen’s d = 0.57, 95% CI [0.02, 0.08], Bonferroni corrected) and neutral (t(118) = 3.71, p = 0.002, Cohen’s d = 0.68, 95% CI [0.03, 0.11], Bonferroni corrected) faces. At T3, the training group only showed a larger improvement in t for the neutral face (t(118) = 3.11, p = 0.012, Cohen’s d = 0.57, 95% CI [0.02, 0.11], Bonferroni corrected). All other differences in other parameters were nonsignificant (all t < 1.8, p > 0.05, Bonferroni corrected).

Correlations between accuracy and ν

As mindfulness training enhanced both the memory accuracy and drift rate, to investigate the associations between the training-induced improvements in these two indicators, we calculated the correlation coefficients between them among individuals in the training group. Results are presented in Table 1. In summary, the accuracy and v had a close relationship within each face category. However, the relationship between categories was weak.

Discussion

Our study demonstrates that mindfulness training significantly enhances working memory accuracy for faces. Meanwhile, DDM analysis revealed accelerated evidence accumulation speed after training, indicating improvements in cognitive processing. Notably, these cognitive improvements exhibit sustained effects over time, underscoring their potential as an intervention for enhancing cognitive performance across diverse populations. Furthermore, we identified a robust positive correlation between working memory accuracy gains and accelerated evidence accumulation, demonstrating that training improves both the precision of face memory and the efficiency of underlying cognitive processes. This converging evidence from accuracy and drift rate results advances our knowledge of the effect of mindfulness training on the working memory process.

In the present study, we found a beneficial impact of mindfulness training on the enhancement of working memory. Previous studies have also indicated that individuals who undergo mindfulness training exhibit a significant increase in their capacity to retain and manipulate information in working memory, such as working memory capacity24,25,26,59,60,61, accuracy62,63, and updating60,64,65,66. The Mindful Coping Model suggests that mindfulness brings about a “decentered” metacognitive state that enhances cognitive flexibility, thereby breaking free from automatic reactive mode, and initiating an adaptive response67,68. The Mindfulness-to-Meaning Theory further posits that mindfulness can neutralize initial cognitive appraisals for stressors in the face of adversity by disrupting the automatic activation of schemata to free one’s focus of attention from rumination on stressors, and foster more flexible and adaptive cognitive processes69. Empirical evidence exhibits that mindful decentering protects the ability to clear irrelevant information from working memory under negative emotional conditions70, and higher working memory capacity predicts greater self-distancing (e.g., decentering)71. Therefore, mindfulness training is an effective tool to enhance individuals’ working memory.

However, the traditional analysis of behavioral performance could not distinguish the changes in cognitive processes and other processes such as response bias or motion execution. The present study utilized the DDM analysis to demonstrate that the changes in v contributed a lot to the training effect on memory accuracy. Meanwhile, mindfulness training does not significantly affect other DDM parameters such as t, z, and a. This suggests that mindfulness training, which targets attentional control and metacognitive awareness, primarily influences the efficiency of cognitive processing rather than other processes during working memory tasks. The a reflects the amount of evidence required before making a response, with higher values indicating a more cautious response strategy. Evidence showed that DDM boundary effects may be more commonly linked to task instructions (e.g., speed-accuracy tradeoffs) than to mindfulness training58. Stable a in the present study suggests mindfulness training did not alter response caution. The z represents a tendency to favor one response (e.g., match vs. non-match) before evidence accumulation begins. Starting-point changes may be primarily produced by changes in prior probability and potential payoff72,73. Stable z in the present study suggests that mindfulness training did not induce response biases. The t captures processes unrelated to evidence accumulation, such as stimulus encoding, motor preparation, and response execution. In the present study, the training group exhibited larger t increases in neutral faces at T2 and T3, indicating prolonged processing of these preparation stages. However, these effects disappeared in emotional faces, suggesting that t is not central to the cognitive mechanism underlying mindfulness training. This interpretation aligns with prior studies showing that mindfulness can not alter nondecision time74,75. However, the influence of facial expressions on nondecision time remains controversial. Some studies revealed emotion-specific effects on the nondecision time76, while others did not find these effects77. A potential explanation for the lack of consistent t effects in our study lies in the prioritized processing of emotional stimuli, which may weaken mindfulness-related modulation of nondecision time. Emotional stimuli are inherently prioritized in cognitive and motivational systems78, and even when emotional expression is irrelevant to the identity-matching task, emotional faces trigger automatic emotion regulation, diverting cognitive resources from motor preparation and response execution. Neurobiologically, this is supported by evidence that emotional faces enhance functional integration between the amygdala and premotor cortices compared to neutral faces79. These findings suggest that nondecision time is a context-dependent measure sensitive to emotional salience, rather than a core marker of mindfulness training effects. These separated parameter outcomes highlight DDM’s capacity to distinguish various components within complex tasks, a critical advantage over conventional behavioral indicators.

Furthermore, we found a robust correlation between accuracy and drift rate for faces sharing identical emotional expressions, suggesting these metrics are rooted in shared underlying mechanisms, confirming the DDM’s remarkable efficacy in cognitive task modeling. The drift rate in the DDM reflects the efficiency of evidence accumulation. The strong convergence of accuracy and drift rate may indicate that mindfulness training simultaneously enhances the precision and efficiency of information processing, both of which share the core cognitive resource. A recent study revealed that drift rate fully mediated the effect of trait anxiety on accuracy in a novel paradigm that combines N-back and Stroop tasks, also revealing the close association between the two factors80. Previous studies have demonstrated that mindfulness training may enhance processing speed81,82 and simultaneously improve decision-making accuracy83,84,85. Consistently, studies concerning the neural correlates of mindfulness training also revealed enhancements in indicators related to the cognitive processing of working memory. For example, electrophysiological evidence suggested that mindfulness training increased P3 amplitude and theta power at electrode site Pz during a 3-back task60. Neuroimaging evidence suggested that mindfulness training enhanced working memory performance, while increasing brain activation in the bilateral inferior parietal lobule, right posterior insula, and right precuneus66. However, it is worth noting that there are other studies showing a beneficial effect of mindfulness training on other processes. For example, a previous study found that meditators showed a modest overall increase in their decision threshold, which may reflect an ability to wait longer and collect more information before responding during the attention network task75. In conclusion, in the present delayed match-to-sample task, we revealed that the beneficial effect of mindfulness training on working memory may be mainly attributable to changes in processing efficiency.

Another important finding of the present study is that the training effect on working memory may not be restricted to faces with specific expressions. We note that the training effect was least evident for fearful faces in the accuracy results. However, the drift rate results revealed a moderate training effect on the fearful faces. A possible explanation for the mere improvement in memory accuracy could be the ceiling effect due to a relatively high baseline accuracy for the fearful face at T1. However, through DDM analysis, we could still reveal a moderate training effect for the fearful face. Although only moderate effects were found for some expressions, our results may reveal a nonspecific cognitive enhancement by mindfulness training, suggesting that the training appears to drive a broad-based improvement in the foundational mechanisms of cognitive processing linked to working memory. Although emotional content was found to affect working memory38,86,87,88, mindfulness may reduce the interference of emotional content on working memory. Mindfulness may potentially free attentional resources typically consumed by affective interference through reducing emotional reactivity, which allows more efficient allocation of working memory resources, and thereby enhances overall working memory performance across all emotional faces. A lot of studies have revealed that mindfulness training reduces emotional reactivity. For example, mindfulness training was associated with attenuated subjective impact of emotional stimuli as well as amygdala deactivation during emotion processing39, and reduced amygdala response to emotional face distractors89 as well as to emotional pictures42. However, it’s worth noting that emotional congruency between the sample and test faces in our DMTS task may modulate the current findings. When the test face matches a sample face, it shares both emotional valence and facial identity with the encoded stimuli. This overlap raises the possibility that performance could reflect perceptual familiarity rather than active working memory maintenance. But from a different perspective, this design is beneficial for controlling interference with memory retrieval of facial identity, which is caused by changes in facial muscles resulting from emotional differences between sample faces and the test face. Future studies should adopt modified designs to isolate memory processing, such as using neutral faces as probes90,91. In conclusion, changes in general working memory related to mindfulness are likely multifaceted, and mindfulness may erect a firewall that shields cognitive processing resources from intrusions by emotional stimuli.

Finally, it is worth noting that there were very weak correlations between enhancements in the working memory of different emotional faces. Several reasons may account for the null findings. First, it may indicate that independent processing mechanisms for different emotions. However, it is still debated whether the processing of basic emotions is independent. Some neuroimaging studies demonstrated distinct neural mechanisms across emotional expressions. For example, there were different activation patterns in the amygdala and frontal cortex when processing fear versus happiness expressions92,93,94 as well as fear versus anger95; the left amygdala, right orbitofrontal cortex, and temporal cortices were involved in the processing of the angry or disgusted expressions, while the right angular gyrus was involved in the processing of happy expressions96. However, there is also evidence that does not support independent processing of different emotions. A perceptual learning study revealed confusion between disgust and anger, as well as the confusion between fear and surprise97. Other studies have also found confusion among the six basic emotions. For example, confusion between fear and surprise has been observed in populations from different cultural backgrounds98,99,100,101,102. Considering the muscular movements involved in the process of generating facial expressions, there is a significant overlap in the movements between expressions of disgust and anger as well as fear and surprise103. Besides, we should note that the weak relationships among the training effects across different face categories do not definitively demonstrate independent emotion-processing mechanisms, as task-specific factors (e.g., perceptual demands of facial feature matching) may also contribute to limited cross-emotion covariance. Future studies combining neuroimaging or electrophysiology with behavioral measures are needed to directly test whether emotional expressions engage distinct neural substrates during mindfulness-enhanced working memory.

There are several limitations in the present study. First, mindfulness training was viewed as a unitary construct without dissociating its core components, such as focused attention, emphasizing engagement with the selected object and disengagement from task-irrelevant distractions and open monitoring, emphasizing moment-by-moment attention to whatever arises in one’s conscious experience, without focusing or elaborating on the content of any particular object23. It may preclude definitive conclusions about whether specific subprocesses (e.g., attentional control vs. emotion regulation) differentially mediate working memory enhancement. Previous studies revealed that open monitoring, rather than focused attention, selectively elicits a more cautious and intentional response style, characterized by increased accuracy, slower reaction times, and diminished P3 amplitude during the Eriksen flanker task104. Direct evidence revealed that, compared to mindfulness-based socioemotional training and mindfulness-based sociocognitive skills, only mindfulness-based attention training enhanced working memory performance105. Future studies need to focus on the effect of discrete facets of mindfulness training.

Second, the present study only focuses on working memory accuracy in the delayed match-to-sample paradigm, which overlooks complementary dimensions of working memory, including capacity, updating, interference susceptibility, etc. Furthermore, the load of working memory was set at one level (i.e., two emotional faces) in the present study. Future research should incorporate multi-task batteries (e.g., the n-back task for updating, the delayed-match-to-sample task for maintenance, and the flanker task for interference control) to examine mindfulness training’s impacts on the multifacet of working memory.

Third, the exclusive use of facial expressions as emotional stimuli restricts generalizability to broader affective processing domains. Mindfulness may have different impacts on working memory for non-facial emotional stimuli. A previous study revealed that the mindfulness group remembered fewer negative words compared to the control group, but there was no difference in the recall of positive words between the two groups106. Systematic comparisons across stimulus modalities in future work could clarify whether the benefits of mindfulness training on working memory reflect domain-specific adaptations or generalized affective processing enhancements.

Fourth, training duration may modulate the effect of mindfulness training. Previous studies demonstrated that working memory performance was affected by mindfulness training with enough training dose25,105,107; and brief mindfulness breathing exercises were not sufficient to enhance working memory capacity30. In the present study, we utilized long-duration mindfulness training. Further studies are required to investigate the impact of mindfulness training with different training doses on working memory, and the effect of emotions.

Fifth, although we ruled out participants with self-reported history of neurological or psychiatric illness, we did not formally evaluate participants’ subclinical symptoms of anxiety or depression using standardized scales. Subclinical emotional symptoms could potentially influence working memory performance108,109 or mindfulness training responsiveness110. Future studies will include validated measures of anxiety and depression to control for baseline emotional states and to stratify participants by symptom severity, enabling subgroup analyses of mindfulness effects in emotionally vulnerable populations.

The last limitation is that the probe stimulus shared emotional valence with sample faces, potentially conflating perceptual familiarity with working memory maintenance. Future studies should use neutral probes to isolate memory processes.

Methods

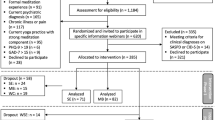

Participants

Sample size was calculated a priori using GPower 3.1 (effect size = 0.50, power = 0.80, α = 0.05). A total sample size of 102 participants was required to detect a significant between-group difference in an independent t test. One hundred and twenty undergraduates were recruited from a medical university by the recruitment advertisement. They were randomly divided into the training group (50 females, age 20.27 ± 1.30) and the control (untrained) group (40 females, age 20.00 ± 0.88). All of the participants were right-handed and had normal or corrected-to-normal vision and normal color vision, and none of them had a history of neurological or psychiatric illness. All participants got paid for participation after completing all tasks.

Measurements

The Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ) was used to measure the mindfulness of participants111. It contains 39 items and encompasses five subscales, including observing (e.g., “When I take a shower or bath, I stay alert to the sensations of water on my body”), describing (e.g., “I can easily put my beliefs, opinions, and expectations into words”), acting with awareness (e.g., “When I do things, my mind wanders off and I’m easily distracted”), non-judging (e.g., “I tell myself I shouldn’t be feeling the way I’m feeling”) and non-reacting (e.g., “When I have distressing thoughts or images, I just notice them and let them go”). All of the items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (very rarely true) to 5 (always true). The Cronbach’s α of the FFMQ was 0.70 in a Chinese non-clinical sample112.

Materials

Digital color pictures depicting emotional faces were adopted from the Chinese Facial Affective Picture System (CFAPS)113. 24 angry faces, 24 sad faces, 24 happy faces, 24 fearful faces, and 24 neutral emotional faces were selected from the system. All pictures had a uniform size (185*200 pixels; visual angle: 5.80°×6.27° at a viewing distance of 60 cm) and were matched for brightness and contrast. The valence for angry, sad, happy, fearful, and neutral faces is 2.70, 3.01, 6.38, 2.84, and 4.31 respectively, while the arousal was 6.18, 5.64, 5.57, 6.49, and 3.85 respectively. ANOVA revealed that the emotional valence was significantly different among face categories (F(4, 115) = 206.33, p < 0.001). Post hoc analysis showed that the emotional valence of the happy face was higher than other faces (all ps < .05, Bonferroni corrected). In addition, the valence of angry, sad, and fearful faces was not significantly different from each other (all ps > 0.05, Bonferroni corrected), which was significantly lower than the neutral face (all ps < 0.05, Bonferroni corrected). Regarding arousal, ANOVA showed a significant difference among categories (F(4, 115) = 19.51, p < 0.001). Post hoc analysis showed that the arousal was significantly lower for the neutral face than other faces (all ps < 0.05, Bonferroni corrected), while the difference among the four emotional faces was nonsignificant (all ps > 0.05, Bonferroni corrected).

Apparatus

The visual stimuli were presented on a SAMSUNG 19-in LCD screen, with a spatial resolution of 1280 × 800 and a refresh rate of 60 Hz114. The subjects viewed the stimuli from a distance of 60 cm. The presentation of stimuli was controlled by E-Prime 2.0 software (https://www.pstnet.com). Data analysis was conducted via SPSS 16.0 (https://www.ibm.com/analytics/SPSS-statistics-software).

Procedure

The protocol of the training program included four phases. The first phase is the baseline test (T1). The second phase is the training phase, in which the training group received a five-week mindfulness training while the control group received two mindfulness lectures. The third phase is the post-training test (T2). The fourth phase is the test one month after the training (T3). The measurements in the three test phases were totally the same for both groups.

At T1, all participants first completed the scale and were then tested with a delayed match-to-sample (DMTS) task in a quiet room. At the beginning of each trial, a white fixation cross was presented in the center of the black screen for a random period of 500 –1500 ms. Then, two faces appeared at two of the four quadrants for 1000 ms. After the disappearance of the sample faces, a blank interval of 2000 ms was presented. Then, a test face was presented at the center of the screen for 1000 ms. Then, the response screen is presented until participants respond. Participants were asked to press one key (F) if the test face matched one of the sample faces and another key (J) if they didn’t match as quickly and accurately as possible. There was no explicit time limit for keypress responses. Keypress responses were permitted both during and after the test face presentation. After the response, a blank screen was presented for 500 ms, and then the next trial began. Each block consisted of 48 trials, in half of which the test face matched the sample face. The emotion of faces in one block was the same across trials. Therefore, each participant completed five blocks, with each block consisting of happy, sad, angry, fearful, and neutral faces respectively. Trial types and the locations of the sample faces were randomly presented in a block, and the block types were counterbalanced among participants. An example of the procedure is demonstrated in Fig. 4.

After the baseline measurement, participants were randomly divided into the training group that received mindfulness training or the control group that attended two lectures about mindfulness. Participants in the training group had systematically participated in the five-week course of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) under the guidance of a therapist who had three years of experience in leading MBSR courses and long-term meditation practice. The mindfulness training program was designed based on the MBSR2 and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT)115. To specifically enhance emotional perception and emotional regulation, the contents of each weekly training focused on the topic of emotion. In each week, participants received a two-hour training course. The contents of the weekly training are shown in Table 2. The control group attended two lectures on mindfulness, which were designed to concentrate on general principles of mindfulness (e.g., definitions, benefits, and everyday applications) and did not include experiential practices. Each lecture lasted 60 min and was conducted by the same instructor leading the MBSR courses. After the training, participants were asked to complete daily mindfulness practice at home and report their feelings.

Immediately after the training (T2), participants were asked to complete the post-training measurement that was the same as the baseline measurement, i.e., the FFMQ scale and the DMTS task. The same test was repeated one month after the training (T3).

After all the measurements were completed, the control group also received mindfulness training if they volunteered to participate.

Statistical analysis

In this study, we measured the level of mindfulness with the FFMQ scale. Therefore, the scores of the scale were first analyzed.

Regarding the DMTS task, behavioral responses were recorded. Mean accuracy and mean reaction time (RT) for the correct responses were calculated for each condition. Then, the discrimination index (d’) for the DMTS task was calculated according to the Signal Detection Theory. Hit rate (H) and False alarm rate (FA) were first calculated, and d’ was calculated as d’ = Z(H) - Z(FA).

Furthermore, a drift-diffusion model (DDM) was constructed based on the responses and RTs in each condition. We utilized the dockerHDDM116 platform to perform the Bayesian hierarchical drift-diffusion modeling. Four basic parameters in the DDM were extracted for each condition and each subject: drift rate (v), decision boundary (a), initial bias (z), and nondecision time (t). In the model fitting, the sample number was set to 10000 samples with 5000 burn-ins to accurately estimate parameters and ensure convergence in hierarchical modeling116. The upper bound of the model is the correct response while the lower bound is the incorrect response.

Before statistical comparisons, we calculated the improvement for each indicator as we focused on the effect of mindfulness training. The scale score, behavioral performance, and modeling parameters before training (at T1) were treated as baselines and were subtracted from the indicators after training (T2 or T3). Specifically, the improvement of an indicator was calculated as the post-training indicator minus the pre-training indicator (T2-T1 or T3-T1). Such manipulation could largely reduce the complexity of our analysis and make our results clear to present. Furthermore, following the group difference analysis, we aimed to investigate the relationship between the training-induced changes in the behavioral performance and modeling parameters, which requires computing the improvements in these indicators. Therefore, the following analyses were all based on the improvements in the indicators.

Afterward, we compared the improvements between the two groups with independent-sample t-tests. The Bonferroni adjustment was applied to address the multiple comparisons issue. Furthermore, to investigate the relationship between the improvements in accuracy and drift rate (v), Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated between the two indicators among individuals in the training group.

Ethics approval

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Ethical Committee of Human Research at Zunyi Medical University (reference number: [2024]1-046) and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all participants before participation.

Data availability

The data supporting this work can be found at https://osf.io/c5x2q/.

Code availability

Custom code or scripts in the generation or analysis of the datasets can be shared upon reasonable request by the corresponding author. Sample size was calculated a priori using GPower 3.1 (https://www.psychologie.hhu.de/arbeitsgruppen/allgemeine-psychologie-und-arbeitspsychologie/gpower). The presentation of stimuli was controlled by E-Prime 2.0 software (https://www.pstnet.com). Data analysis was conducted via SPSS 16.0 (https://www.ibm.com/analytics/SPSS-statistics-software). The Bayesian hierarchical drift-diffusion modeling was performed via dockerHDDM116.

References

Academic Mindfulness Interest Group, M. & Academic Mindfulness Interest Group, M. Mindfulness-based psychotherapies: A review of conceptual foundations, empirical evidence and practical considerations. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 40, 285–294 (2006).

Kabat-Zinn, J. Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom books of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness (Delta Books, 1990).

Chiesa, A., Calati, R. & Serretti, A. Does mindfulness training improve cognitive abilities? A systematic review of neuropsychological findings. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 31, 449–464 (2011).

Christoff Hadjiilieva, K. Mindfulness as a way of reducing automatic constraints on thought. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging 10, 393–401 (2025).

Kang, Y., Gruber, J. & Gray, J. R. Mindfulness and de-automatization. Emot. Rev. 5, 192–201 (2013).

Kang, Y., Gruber, J. & Gray, J. R. The Wiley Blackwell handbook of mindfulness, Vols. I and II 168–185 (Wiley Blackwell, 2014).

Droit-Volet, S., Chaulet, M. & Dambrun, M. Time and meditation: When does the perception of time change with mindfulness exercise?. Mindfulness 9, 1557–1570 (2018).

Vencatachellum, S., van der Meulen, M., Van Ryckeghem, D. M. L., Van Damme, S. & Vögele, C. Brief mindfulness training can mitigate the influence of prior expectations on pain perception. Eur. J. Pain. 25, 2007–2019 (2021).

Lu, C., Moliadze, V. & Nees, F. Dynamic processes of mindfulness-based alterations in pain perception. Front. Neurosci. 17, 1253559 (2023).

Felver, J. C., Tipsord, J. M., Morris, M. J., Racer, K. H. & Dishion, T. J. The effects of mindfulness-based intervention on children’s attention regulation. J. Atten. Disord. 21, 872–881 (2017).

Mak, C., Whittingham, K., Cunnington, R. & Boyd, R. N. Efficacy of Mindfulness-Based Interventions for Attention and Executive Function in Children and Adolescents—a Systematic Review. Mindfulness 9, 59–78 (2018).

Kohler, M., Rawlings, M., Kaeding, A., Banks, S. & Immink, M. A. Meditation is effective in reducing sleepiness and improving sustained attention following acute sleep restriction. J. Cogn. Enhancement 1, 210–218 (2017).

Verhaeghen, P. Mindfulness as attention training: Meta-analyses on the links between attention performance and mindfulness interventions, long-term meditation practice, and trait mindfulness. Mindfulness 12, 564–581 (2021).

de Bruin, E. I., van der Zwan, J. E. & Bögels, S. M. A RCT comparing daily mindfulness meditations, biofeedback exercises, and daily physical exercise on attention control, executive functioning, mindful awareness, self-compassion, and worrying in stressed young adults. Mindfulness 7, 1182–1192 (2016).

Shemesh, L., Mendelsohn, A., Panitz, D. Y. & Berkovich-Ohana, A. Enhanced declarative memory in long-term mindfulness practitioners. Psychol. Res. 87, 294–307 (2023).

Dominguez, E., Casagrande, M. & Raffone, A. Autobiographical memory and mindfulness: A critical review with a systematic search. Mindfulness 13, 1614–1651 (2022).

Youngs, M. A., Lee, S. E., Mireku, M. O., Sharma, D. & Kramer, R. S. S. Mindfulness meditation improves visual short-term memory. Psychol. Rep. 124, 1673–1686 (2021).

Baddeley, A. Working memory. Curr. Biol. 20, R136–R140 (2010).

Baddeley, A. The episodic buffer: a new component of working memory?. Trends Cogn. Sci. 4, 417–423 (2000).

Holas, P. & Jankowski, T. A cognitive perspective on mindfulness. Int. J. Psychol. 48, 232–243 (2013).

Jensen, C. G., Vangkilde, S., Frokjaer, V. & Hasselbalch, S. G. Mindfulness training affects attention—Or is it attentional effort?. J. Exp. Psychol.: Gen. 141, 106–123 (2012).

Zeidan, F., Johnson, S. K., Diamond, B. J., David, Z. & Goolkasian, P. Mindfulness meditation improves cognition: Evidence of brief mental training. Conscious. Cognit. 19, 597–605 (2010).

Jha, A. P. et al. Does mindfulness training help working memory ‘work’ better?. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 28, 273–278 (2019).

Jha, A. P., Stanley, E. A., Kiyonaga, A., Wong, L. & Gelfand, L. Examining the protective effects of mindfulness training on working memory capacity and affective experience. Emotion 10, 54–64 (2010).

Mrazek, M. D., Franklin, M. S., Phillips, D. T., Baird, B. & Schooler, J. W. Mindfulness training improves working memory capacity and GRE performance while reducing mind wandering. Psychol. Sci. 24, 776–781 (2013).

Quach, D., Jastrowski Mano, K. E. & Alexander, K. A Randomized Controlled Trial Examining the Effect of Mindfulness Meditation on Working Memory Capacity in Adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 58, 489–496 (2016).

Im, S. et al. Does mindfulness-based intervention improve cognitive function?: A meta-analysis of controlled studies. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 84, 101972 (2021).

Yakobi, O., Smilek, D. & Danckert, J. The Effects of Mindfulness Meditation on Attention, Executive Control and Working Memory in Healthy Adults: A Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Cogn. Ther. Res. 45, 543–560 (2021).

Baranski, M. F. S. & Was, C. A. A more rigorous examination of the effects of mindfulness meditation on working memory capacity. J. Cogn. Enhancement 2, 225–239 (2018).

Quek, F. Y. X. et al. Brief mindfulness breathing exercises and working memory capacity: Findings from two experimental approaches. Brain Sci. 11, 175 (2021).

Hou, T. Y. & Cai, W. P. What emotion dimensions can affect working memory performance in healthy adults? A review. World J. Clin. Cases 10, 401–411 (2022).

Lee, H. J. & Cho, Y. S. Memory facilitation for emotional faces: Visual working memory trade-offs resulting from attentional preference for emotional facial expressions. Mem. Cognit. 47, 1231–1243 (2019).

Jackson, M. C., Linden, D. E. J. & Raymond, J. E. Angry expressions strengthen the encoding and maintenance of face identity representations in visual working memory. Cognit. Emot. 28, 278–297 (2014).

Kou, H. et al. Cognitive deficits for facial emotions among male adolescent delinquents with conduct disorder. Front. Psychiatry 13, 937754 (2022).

Zhang, J., Guan, W. & Lipp, O. V. The effect of emotion counter-regulation to anger on working memory updating. Psychophysiology 60, e14366 (2023).

Nejati, V., Majidinezhad, M. & Nitsche, M. The role of the dorsolateral and ventromedial prefrontal cortex in emotion regulation in females with major depressive disorder (MDD): A tDCS study. J. Psychiatr. Res. 148, 149–158 (2022).

Kensinger, E. A. & Corkin, S. Effect of negative emotional content on working memory and long-term memory. Emotion 3, 378–393 (2003).

Levens, S. M. & Phelps, E. A. Emotion processing effects on interference resolution in working memory. Emotion 8, 267–280 (2008).

Taylor, V. A. et al. Impact of mindfulness on the neural responses to emotional pictures in experienced and beginner meditators. NeuroImage 57, 1524–1533 (2011).

Wu, R. et al. Brief mindfulness meditation improves emotion processing. Front. Neurosci. 13, 1074 (2019).

Correia, P. et al. Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction meditation on the emotional reaction to affective pictures assessed by electrodermal activity. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 86, 105314 (2023).

Kral, T. R. A. et al. Impact of short- and long-term mindfulness meditation training on amygdala reactivity to emotional stimuli. NeuroImage 181, 301–313 (2018).

Li, X., O’Sullivan, M. J. & Mattingley, J. B. Delay activity during visual working memory: A meta-analysis of 30 fMRI experiments. Neuroimage 255, 119204 (2022).

Lin, C.-C. et al. Up-regulation of proactive control is associated with beneficial effects of a childhood gymnastics program on response preparation and working memory. Brain Cognit. 149, 105695 (2021).

Hasselmo, M. E. & Stern, C. E. Mechanisms underlying working memory for novel information. Trends Cogn. Sci. 10, 487–493 (2006).

Lin, C. C. et al. The unique contribution of motor ability to visuospatial working memory in school-age children: Evidence from event-related potentials. Psychophysiology 60, e14182 (2023).

Borghans, L. & Princen, M. The stability of memory performance using an adapted version of the Delayed Matching To Sample task: An ERP study. Maastricht Student. J. Psychol. Neurosci. 1, 9–18 (2012).

Daniel, T. A., Katz, J. S. & Robinson, J. L. Delayed match-to-sample in working memory: A BrainMap meta-analysis. Biol. Psychol. 120, 10–20 (2016).

Stafford, T., Pirrone, A., Croucher, M. & Krystalli, A. Quantifying the benefits of using decision models with response time and accuracy data. Behav. Res. Methods 52, 2142–2155 (2020).

Ratcliff, R., Smith, P. L., Brown, S. D. & McKoon, G. Diffusion Decision Model: Current Issues and History. Trends Cogn. Sci. 20, 260–281 (2016).

Pedersen, M. L., Frank, M. J. & Biele, G. The drift diffusion model as the choice rule in reinforcement learning. Psychonomic Bull. Rev. 24, 1234–1251 (2017).

Bottemanne, L. & Dreher, J.-C. Vicarious rewards modulate the drift rate of evidence accumulation from the drift diffusion model. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 13, https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2019.00142 (2019).

Parker, S. & Ramsey, R. What can evidence accumulation modelling tell us about human social cognition?. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. (Hove) 77, 639–655 (2024).

Copeland, A., Tom, S. & Field, M. Methodological issues with value-based decision-making (VBDM) tasks: The effect of trial wording on evidence accumulation outputs from the EZ drift-diffusion model. Cogent Psychol. 9, 2079801 (2022).

Zilker, V. Attentional dynamics of evidence accumulation explain why more numerate people make better decisions under risk. Sci. Rep. 14, 18788 (2024).

Cochrane, A., Sims, C. R., Bejjanki, V. R., Green, C. S. & Bavelier, D. Multiple timescales of learning indicated by changes in evidence-accumulation processes during perceptual decision-making. npj Sci. Learn. 8, 19 (2023).

Reinhartz, A., Strobach, T., Jacobsen, T. & von Bastian, C. C. Mechanisms of training-related change in processing speed: A drift-diffusion model approach. J. Cognit. 6, 46 (2023).

Zhang, J. & Rowe, J. B. Dissociable mechanisms of speed-accuracy tradeoff during visual perceptual learning are revealed by a hierarchical drift-diffusion model. Front. Neurosci. 8, 00069 (2014).

Jha, A. P., Zanesco, A. P., Denkova, E., MacNulty, W. K. & Rogers, S. L. The effects of mindfulness training on working memory performance in high-demand cohorts: A multi-study investigation. J. Cogn. Enhancement 6, 192–204 (2022).

Hunter, M. A. et al. Mindfulness-based training with transcranial direct current stimulation modulates neuronal resource allocation in working memory: A randomized pilot study with a nonequivalent control group. Heliyon 4, e00685 (2018).

Axelsen, J. L., Meline, J. S. J., Staiano, W. & Kirk, U. Mindfulness and music interventions in the workplace: assessment of sustained attention and working memory using a crowdsourcing approach. BMC Psychol. 10, 108 (2022).

Bailey, N. W. et al. Mindfulness meditators show enhanced accuracy and different neural activity during working memory. Mindfulness 11, 1762–1781 (2020).

Zainal, N. H. & Newman, M. G. Mindfulness enhances cognitive functioning: a meta-analysis of 111 randomized controlled trials. Health Psychol. Rev. 18, 369–395 (2024).

Cásedas, L., Pirruccio, V., Vadillo, M. A. & Lupiáñez, J. Does mindfulness meditation training enhance executive control? a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials in adults. Mindfulness 11, 411–424 (2020).

Zhou, H., Liu, H. & Deng, Y. Effects of short-term mindfulness-based training on executive function: Divergent but promising. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 27, 672–685 (2020).

Bachmann, K. et al. Effects of mindfulness and psychoeducation on working memory in adult ADHD: A randomised, controlled fMRI study. Behav. Res. Ther. 106, 47–56 (2018).

Garland, E. L. The meaning of mindfulness: A second-order cybernetics of stress, metacognition, and coping. Complementary Health Pract. Rev. 12, 15–30 (2007).

Garland, E., Gaylord, S. & Park, J. The role of mindfulness in positive reappraisal. Explore 5, 37–44 (2009).

Garland, E. L., Farb, N. A., Goldin, P. R. & Fredrickson, B. L. The mindfulness-to-meaning theory: Extensions, applications, and challenges at the attention–appraisal–emotion interface. Psychol. Inq. 26, 377–387 (2015).

Kaiser, R. H., Andrews-Hanna, J. R., Metcalf, C. A. & Dimidjian, S. Dwell or decenter? rumination and decentering predict working memory updating after interpersonal criticism. Cogn. Ther. Res. 39, 744–753 (2015).

Seah, T. H. S., Matt, L. M. & Coifman, K. G. Spontaneous self-distancing mediates the association between working memory capacity and emotion regulation success. Clin. Psychol. Sci. 9, 79–96 (2021).

Leite, F. P. & Ratcliff, R. What cognitive processes drive response biases? A diffusion model analysis. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 6, 651–687 (2011).

Mulder, M. J., Wagenmakers, E. J., Ratcliff, R., Boekel, W. & Forstmann, B. U. Bias in the brain: A diffusion model analysis of prior probability and potential payoff. J. Neurosci. 32, 2335–2343 (2012).

van Vugt, M. K. & Jha, A. P. Investigating the impact of mindfulness meditation training on working memory: A mathematical modeling approach. Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 11, 344–353 (2011).

van Vugt, M. K. & van den Hurk, P. M. Modeling the effects of attentional cueing on meditators. Mindfulness 8, 38–45 (2017).

Tipples, J. Caution follows fear: Evidence from hierarchical drift diffusion modelling. Emotion 18, 237–247 (2018).

Mueller, C. J., White, C. N. & Kuchinke, L. Individual differences in emotion processing: how similar are diffusion model parameters across tasks?. Psychol. Res. 83, 1172–1183 (2019).

Okon-Singer, H., Lichtenstein-Vidne, L. & Cohen, N. Dynamic modulation of emotional processing. Biol. Psychol. 92, 480–491 (2013).

Diano, M. et al. Dynamic Changes in Amygdala Psychophysiological Connectivity Reveal Distinct Neural Networks for Facial Expressions of Basic Emotions. Sci. Rep. 7, 45260 (2017).

Sun, Y., Lin, Y. & Han, S. Inhibition and updating share common resources: Bayesian evidence from signal detection theory and drift diffusion model. Psychol. Res. 89, 128 (2025).

Manglani, H. R., Samimy, S., Schirda, B., Nicholas, J. A. & Prakash, R. S. Effects of 4-week mindfulness training versus adaptive cognitive training on processing speed and working memory in multiple sclerosis. Neuropsychology 34, 591–604 (2020).

Heredia, L., Ventura, D., Torrente, M. & Vicens, P. An 8-week secular mindfulness-based training program for schoolteachers increases dispositional mindfulness, self-reported workplace well-being, visuoconstructive abilities, and processing speed. Mind, Brain, Educ. 18, 236–248 (2024).

Darses, F. et al. Effects of mindfulness training on decision-making in critical and high-demand situations: A pilot study in combat aviation. Saf. Sci. 166, 106204 (2023).

Mirams, L., Poliakoff, E., Brown, R. J. & Lloyd, D. M. Brief body-scan meditation practice improves somatosensory perceptual decision making. Conscious. Cognit. 22, 348–359 (2013).

Im, S., Marder, M. A., Imbriano, G., Sussman, T. J. & Mohanty, A. Effects of a brief mindfulness-based attentional intervention on threat-related perceptual decision-making. Mindfulness 12, 959–969 (2021).

Lindström, B. R. & Bohlin, G. Emotion processing facilitates working memory performance. Cognit. Emot. 25, 1196–1204 (2011).

Grimm, S., Weigand, A., Kazzer, P., Jacobs, A. M. & Bajbouj, M. Neural mechanisms underlying the integration of emotion and working memory. NeuroImage 61, 1188–1194 (2012).

Garrison, K. E. & Schmeichel, B. J. Effects of emotional content on working memory capacity. Cognit. Emot. 33, 370–377 (2019).

Dumontheil, I., Lyons, K. E., Russell, T. A. & Zelazo, P. D. A preliminary neuroimaging investigation of the effects of mindfulness training on attention reorienting and amygdala reactivity to emotional faces in adolescent and adult females. J. Adolesc. 95, 181–189 (2023).

Valenti, L. et al. Emotional intensity plays an important role in working memory metacognition. Psychol. Neurosci. 18, 269–283 (2025).

Zhou, L., Liu, M., Ye, B., Wang, X. & Liu, Q. Sad expressions during encoding enhance facial identity recognition in visual working memory in depression: Behavioural and electrophysiological evidence. J. Affect. Disord. 279, 630–639 (2021).

Morris, J. S. et al. A differential neural response in the human amygdala to fearful and happy facial expressions. Nature 383, 812–815 (1996).

Rahko, J. et al. Functional mapping of dynamic happy and fearful facial expression processing in adolescents. Brain Imaging Behav. 4, 164–176 (2010).

Suk, J.-W. et al. Mediating effect of amygdala activity on response to fear vs. happiness in youth with significant levels of irritability and disruptive mood and behavior disorders. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 17, 1204574 (2023).

Whalen, P. J. et al. A functional MRI study of human amygdala responses to facial expressions of fear versus anger. Emotion 1, 70–83 (2001).

Iidaka, T. et al. Neural interaction of the amygdala with the prefrontal and temporal cortices in the processing of facial expressions as revealed by fMRI. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 13, 1035–1047 (2001).

Wang, Y., Zijian, Z., Biqing, C. & Fang, F. Perceptual learning and recognition confusion reveal the underlying relationships among the six basic emotions. Cognit. Emot. 33, 754–767 (2019).

Beaupré, M. G. & Hess, U. Cross-cultural emotion recognition among canadian ethnic groups. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 36, 355–370 (2005).

Jack, R. E., Garrod, O. G. B., Yu, H., Caldara, R. & Schyns, P. G. Facial expressions of emotion are not culturally universal. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 109, 7241–7244 (2012).

Matsumoto, D. American-Japanese Cultural Differences in the Recognition of Universal Facial Expressions. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 23, 72–84 (1992).

McAndrew, F. T. A cross-cultural study of recognition thresholds for facial expressions of emotion. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 17, 211–224 (1986).

Russell, J. A. Is there universal recognition of emotion from facial expression? A review of the cross-cultural studies. Psychol. Bull. 115, 102–141 (1994).

Jack, R. E., Garrod, O. G. B. & Schyns, P. G. Dynamic facial expressions of emotion transmit an evolving hierarchy of signals over time. Curr. Biol. 24, 187–192 (2014).

Lin, Y., White, M. L., Viravan, N. & Braver, T. S. Parsing state mindfulness effects on neurobehavioral markers of cognitive control: A within-subject comparison of focused attention and open monitoring. Cogn., Affect., Behav. Neurosci. 24, 527–551 (2024).

Böckler, A. & Singer, T. Longitudinal evidence for differential plasticity of cognitive functions: Mindfulness-based mental training enhances working memory, but not perceptual discrimination, response inhibition, and metacognition. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 151, 1573–1590 (2022).

Alberts, H. J. E. M. & Thewissen, R. The effect of a brief mindfulness intervention on memory for positively and negatively valenced stimuli. Mindfulness 2, 73–77 (2011).

Zanesco, A. P., Denkova, E., Rogers, S. L., MacNulty, W. K. & Jha, A. P. Progress in Brain Research (ed Narayanan Srinivasan) Vol. 244, 323–354 (Elsevier, 2019).

Živković, M., Pellizzoni, S., Mammarella, I. C. & Passolunghi, M. C. The relationship betweens math anxiety and arithmetic reasoning: The mediating role of working memory and self-competence. Curr. Psychol. 42, 14506–14516 (2023).

McArthur, G. E., Lee, E. & Laycock, R. Autism Traits and Cognitive Performance: Mediating Roles of Sleep Disturbance, Anxiety and Depression. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 53, 4560–4576 (2023).

Kou, H. et al. The sustained effect of 5-week EmotionCore mindfulness training on emotion regulation and emotional intelligence: Heterogeneous benefits for depression and anxiety across subgroups. Front. Psychiatry 16, 1622626 (2025).

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Hopkins, J., Krietemeyer, J. & Toney, L. Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment 13, 27–45 (2006).

Deng, Y.-Q., Liu, X.-H., Rodriguez, M. A. & Xia, C.-Y. The five facet mindfulness questionnaire: Psychometric properties of the Chinese version. Mindfulness 2, 123–128 (2011).

Gong, X., Huang, Y.-X., Wang, Y. & Luo, Y.-J. Revision of the Chinese facial affective picture system. Chin. Ment. Health J. 25, 40–46 (2011).

Zhang, G. et al. A consumer-grade LCD monitor for precise visual stimulation. Behav. Res. Methods 50, 1496–1502 (2018).

Segal, Z. V., Teasdale, J. D., Williams, J. M. & Gemar, M. C. The mindfulness-based cognitive therapy adherence scale: inter-rater reliability, adherence to protocol and treatment distinctiveness. Clin. Psychol. Psychother. 9, 131–138 (2002).

Pan, W. et al. dockerHDDM: A user-friendly environment for Bayesian hierarchical drift-diffusion modeling. Adv. Methods Pract. Psychol. Sci. 8, 25152459241298700 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Guizhou Provincial Science and Technology Projects [QKHJC[2024] Youth 309, Guizhou platform talents[2021] 1350-046], Zunyi Science and Technology Cooperation [HZ(2024)311], Funding of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (2024SYZH005), Peking University Longitudinal Scientific Research Technical Service Project (G-252).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.K.: Conceptualization, Resources, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing-review & editing, Visualization, Supervision. W.L.: Conceptualization, Resources, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Formal analysis, Writing-review & editing, Visualization, Supervision. X.L.: Methodology, Resources, Investigation. J.W.: Methodology, Resources, Investigation. Q.X.: Conceptualization, Resources, Formal analysis, Writing-review & editing, Data Curation, Project administration, Visualization, Supervision. T.B.: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Resources, Formal analysis, Writing-review & editing, Data Curation, Project administration, Visualization, Supervision.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kou, H., Luo, W., Li, X. et al. Mindfulness training enhances face working memory: evidence from the drift-diffusion model. npj Sci. Learn. 11, 7 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41539-025-00389-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41539-025-00389-0