Abstract

Attending a lecture requires remaining focused for extended periods, which is particularly difficult in noisy environments or when lecture content is less engaging. Yet little is known about how these external (noise) and internal (interest) factors affect learners’ neurophysiology. We measured brain activity (electroencephalogram; EEG) and physiological responses (skin conductance) during video-based learning, and assessed how neurophysiological responses were modulated by the presence of realistic background noise and by varying levels of interest throughout the lecture. Interest-level showed pronounced neurophysiological effects, with low-interest segments associated with reduced neural speech tracking, elevated alpha-power, reduced beta-power, and increased arousal, a pattern consistent with lower engagement and increased listening effort. Interestingly, background noise had comparatively limited effects on neurophysiological responses. These dissociated impacts of internal and external factors on speech processing during learning, emphasize the profound impact of content-engagement on neurophysiological measures associated with learner’s attention, beyond the sensory burden of noise.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Listening to a lecture, whether in a traditional classroom setting or via online platforms, requires individuals to focus their attention on the teacher for a long period of time1,2,3. However, many factors—external and internal—can make sustained attention to a lecture difficult4,5. For example, the presence of background noise may distract listeners from the lecture or make hearing more difficult6,7,8,9, and features related to the lecture content or delivery (e.g., the speaker’s charisma or presentation style) or to the listeners themselves (e.g., interest in the topic) may prompt mind-wandering or off-task behavior10,11. Despite ample behavioral evidence (and decades-long introspective insight) that attention can vary and fluctuate throughout a long lecture, our current understanding of the neurophysiological manifestations of these fluctuations, and the factors influencing them, is extremely limited.

The disruptive impact of external noise on speech-processing has been studied extensively. It is well established that the presence of background noise can reduce speech intelligibility12,13,14,15 and requires investing more effort due to the increased perceptual and cognitive load14,16,17. Consequently, this can lead to elevated stress levels18,19 and reduced neural encoding of the speech17,20,21. That said, not all noise has the same disruptive effects, but can vary as a function of sound-level, temporal structure, contextuality and noise-type22,23,24,25, and moderate noise can sometimes even improve performance, in line with the notion of an inverted U-shape relationship between arousal and performance26,27,28,29,30 and the moderate brain arousal model31,32,33. Therefore, simply assuming that adding noise is detrimental to speech processing, and consequently impairs attention to speech, is not straightforward.

Importantly, insights gained from traditional speech-in-noise studies might not generalize fully to more ecological contexts, such as listening to a full lecture34,35,36. One reason for this is the prevalent use of short, highly edited sentences as stimuli that lack the context and semantic continuity of a lecture37. Real-life speech, and particularly a lecture, is continuous and contextual, with a structured narrative and built-in redundancies, factors that are designed to engage listeners, hold their attention over time, and which can also potentially mitigate the masking effects of noise. However, as anyone who has ever attended a frontal lecture can attest—it is precisely the continuous nature of lectures that renders their quality non-uniform over time. In stark opposition from the well-controlled stimuli of experimental designs (including highly edited and rehearsed audiobooks30,38 or TED-style talks), the speech in live lectures is generated by the instructor ‘on the fly’ and therefore can contain frequent disfluencies, repetitions, ill-formed sentences and rambling39,40. In addition, the content itself can vary in its clarity, novelty and interest to the listener as well as speaker eloquence, style and charisma. These variations in quality over time impact listeners’ level of engagement and sustained attention to speech, with more engaging and interesting content leading to higher levels attentional focus and reduced processing load1, and reduced interest associated with mind-wandering and off-task behaviors41,42,43. The current study broadens the scope of investigation of natural speech processing to assess the independent effects of external background noise and of non-uniform levels of interest. We focus specifically on “situational interest”, a term used in educational and psychological research to describe fluctuations in interest that are common to most people and can be attributed to variations in features of the lecture itself such as clarity, novelty, relevance, speaker charisma, use of humor etc10,44,45,46,47. This is distinct from “individual interest” which reflects personal preference for specific topics or other contextual influences that contribute to individual differences, but is beyond the scope of the current study48,49,50,51.

Our aim was to examine how external noise and fluctuations in situational interest-levels influence speech processing under naturalistic conditions that require sustained attention, and to link these effects to changes in neurophysiological metrics associated with arousal, attention and speech processing. To this end, we measured neural activity (electroencephalogram; EEG) and physiological responses (skin-conductance) while individuals watched an unedited video recording of a real-life frontal-lecture. We chose a lecture that was aimed for a general public audience, on a relatively unknown topic (Agism). The lecture was rated as “relatively interesting” in a pre-screening stage and contained substantial minute-by-minute variability in listeners’ reported interest ratings (details below). Group-level interest ratings were used to split the lecture into portions with high vs. low levels of situational interest. In addition, we manipulated the presence and type of background noise by playing two types of construction sounds—intermittent and continuous—in 2/3rds of the trials9. We tested how these two factors—external noise and situational interest—affected specific physiological and neural metrics associated with arousal, attention and speech processing. These included: (a) Neural speech-tracking, which reflects neural encoding of the speech itself and is known to be reduced under conditions of decreased attention and/or poor speech intelligibility52,53; (b) Neural alpha-band oscillations, which are often increased under conditions of low-attention and mind-wandering54; (c) Neural beta-oscillations, which are associated with cognitive processing and tend to increase under heightened task demands55,56,57; and (d) Skin-conductance, which reflects level of arousal and is often affected by stress and cognitive or perceptual effort55,58. Based on previous studies and the hypothesized functional role of these neurophysiological metrics, we expected to find that during quiet portions of the lecture (without background noise) and portions reported as highly interesting, neural tracking of the speech would be improved, we would find lower alpha power and higher beta power, and modulation of skin conductance, a metric linked to levels of arousal, relative to portions that contained additional noise and/or that were rated as less interesting.

Results

Behavioral data

We analyzed the ratings of situational interest for the different lecture-segments. First, we compared the reported levels of interest across segments between these data and an online screening study. Overall interest ratings were slightly higher in the current study (M = 4.73, SD = 0.34) than in the online study (M = 4.28, SD = 0.41) [t(61) = 15.32, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 1.946; Fig. 1A], which may indicate overall higher engagement when performing the task in a lab vs. alone and online. Despite this ‘baseline shift’, we found that the variation in interest-level ratings for the different lecture-segments, where highly correlated between the two studies [Pearson’s r = 0.827, p < 0.001, Fisher’s z = 1.178; Fig. 1B]. This supports the utility of interest-ratings as objective metrics of variation in situational interest across the entire lecture, despite potential differences in individual interest and subjective experience (Song et al. 2021). Accuracy on answering comprehension questions about the lecture content was also generally good (M = 87% correct, SD = 13.22), and was comparable to the online study [M = 86.2% correct, SD = 15.23; comparison between lab and online studies: t(29) = 0.468, p = 0.643, Cohen’s d = 0.08].

A Average interest values for each lecture segment in the online screening study (n = 37; gray line) and the EEG study (n = 32; black line). Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (SEM). B Pearson correlation between average interest ratings in the EEG and online studies across lecture segments (r = 0.83, p < 0.001). C, D Box plots showing the distribution of C accuracy scores (percentage of correct answers) and D interest ratings1,2,3,4,5,6,7, across noise conditions. E Box plot showing the distribution of accuracy scores for lecture segments rated as high vs. low in interest. In all box plots, red lines indicate the median, boxes represent the interquartile range (IQR), whiskers extend to 1.5×IQR, and individual dots represent participants’ data points.

Behavioral analysis of accuracy on comprehension questions and interest level ratings showed no significant effect of noise condition [repeated measures ANOVA: Accuracy - F(2,62) = 2.098, p = 0.13; Interest levels - F(2,62) = 1.149, p = 0.324; Fig. 1C, D], suggesting that the addition of noise did not impact performance or interest-ratings.

However, when comparing accuracy on comprehension questions for segments rated as high vs. low interest (median split), we found a marginally significant effect suggesting improved comprehension for lecture segments rated as more interesting [M = 89.76%, SD = 11.07 vs. M = 83.94%, SD = 15.61, respectively; t(28) = 1.856, p = 0.074, Cohen’s d = 0.345; Fig. 1E].

Galvanic Skin Response (GSR) data

We extracted two main metrics from the GSR data: (1) the mean phasic activity, representing short-term fluctuations in skin conductance, and (2) the mean tonic activity, reflecting the slower, sustained level of arousal.

Repeated-measures ANOVA comparing these metrics between the three noise conditions revealed significant differences between them in the mean tonic activity [F(2,62) = 20.923, p < 0.001; Table 1, Fig. 2A]. Follow-up pairwise analyses of differences in tonic GSR levels revealed higher responses in the noise conditions (average between intermittent and continuous conditions) relative to the quiet condition [t(31) = 3.15; p < 0.005, Cohen’s d = 0.55], and higher response in the intermittent vs. continuous noise conditions [t(31) = 5.552; p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.98] with a large effect size in both. In contrast, the mean phasic activity did not differ significantly between conditions [F(2,62) = 1.182, p = 0.314; Table 1, Fig. 2B].

Box plots show the distribution of A mean tonic activity and B mean phasic activity, both in microsiemens. The phasic average is shown as a representative phasic measure, as all phasic metrics showed similar patterns. In both panels, red lines indicate the median, boxes represent the IQR, whiskers extend to 1.5×IQR, and individual dots represent participants’ data points.

We next tested whether the GSR metrics were modulated by the level of interest across lecture segments. Both main metrics showed significantly higher activity during low- compared to high-interest segments [mean tonic activity: t(31) = 4.326, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.76; mean phasic activity: t(31) = 3.566, p = 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.63; Table 1, Fig. 3].

Box plots show the distribution of A mean tonic activity and B mean phasic activity (x10) in microsiemens, for lecture segments rated as high vs. low in interest. The mean phasic activity is shown as a representative phasic measure, as all phasic metrics showed similar effects. In both panels, red lines indicate the median, boxes represent the IQR, whiskers extend to 1.5×IQR, and individual dots represent participants’ data points.

Neural data: Speech tracking analysis

We estimated Temporal response functions (TRFs) to the speech stimulus separately for the three conditions (quiet, continuous noise, intermittent noise). All conditions showed clusters of electrodes with significant predictive power relative to a null distribution, indicating reliable speech tracking. Notably, the number of significant electrodes varied across conditions, with the fewest in the intermittent-noise condition (six electrodes; cluster corrected) and the most in the continuous-noise condition (27 electrodes; cluster corrected).

To assess the effect of noise on speech tracking, we compared the TRFs in the quiet condition to the average TRFs across both noise conditions [Fig. 4A], and also compared the TRFs in the two noise conditions to each other [continuous vs. intermittent; Fig. 4B]. All TRFs showed two prominent positive peaks, approximately around 200 and 350 ms, which were maximal in mid-central electrodes. These peaks were modulated by noise in the following way [Fig. 4A–C]: The early peak (~200 ms) was significantly larger in the quiet condition vs. noise [p < 0.002, cluster-corrected], and larger for intermittent vs. continuous noise [p < 0.03, cluster-corrected]. The later peak (~350 ms) was larger in the noise vs. quiet conditions [p < 0.004, cluster-corrected] and was larger in for continuous vs. intermittent noise [p < 0.002, cluster-corrected]. A complementary decoding analysis, which estimates the overall accuracy of reconstructing a speech stimulus from the recorded EEG, also showed significant modulation by noise condition (Fig. 4D). A repeated-measures ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of noise condition on decoding accuracy [F(2,62) = 6.846, p = 0.002; Table 1], and post hoc pairwise comparisons (Holm-corrected for multiple comparisons) indicated significantly better decoding performance in the continuous noise condition compared to both the quiet condition [t(31) = 3.020, p = 0.007, Cohen’s d = 0.37] and the intermittent noise condition [t(31) = 3.362, p = 0.004, Cohen’s d = 0.41].

A, B TRFs for A quiet (red) vs. noise (purple) conditions, and B continuous (green) vs. intermittent (blue) noise conditions, averaged across electrodes showing significant speech tracking. Shaded gray areas indicate time windows with significant differences between conditions. C Topographical maps showing clusters of electrodes with significant differences in TRF amplitudes (p < 0.05, corrected; white circles) during the relevant time windows for the noise vs. quiet and continuous vs. intermittent comparisons. D Box plot showing the distribution of speech reconstruction accuracy (r values) of the decoding model across conditions. Red lines indicate the median, boxes represent the IQR, whiskers extend to 1.5×IQR, and individual dots represent participants’ data points.

To assess whether neural tracking of the speech was modulated by situational level of interest, we estimated TRFs separately for segments rated as high- and low-interest. A similar number of electrodes shows significant speech-tracking responses in both conditions, relative to a null distribution (33 and 34 electrodes, respectively). The TRF amplitudes were significantly modulated by level of interest as follows: Two prominent TRF peaks – an early negative peak (~160 ms) and a late positive peak (~350 ms) were larger in the high vs. low interest condition, while the intermediate positive peak (~200 ms) was larger in the low interest condition [all p’s<0.02, cluster-corrected; Fig. 5A, B]. The complementary decoding analysis also showed that the speech stimulus could be reconstructed more accurately in the high vs. low interest condition [t(31) = 3.17, p = 0.003, Cohen’s d = 0.56; Table 1, Fig. 5C].

A TRFs for high (black) vs. low (gray) interest segments, averaged across electrodes showing significant speech tracking. The shaded gray area indicates a time windows with a significant difference between conditions (p < 0.05, corrected). B Topographical map showing electrodes with significant differences in TRF amplitudes (p < 0.05, corrected; white circles) during the significant time windows. C Box plot showing the distribution of speech reconstruction accuracy (r values) of the decoding model for high vs. low interest conditions. Red lines indicate the median, boxes represent the IQR, whiskers extend to 1.5×IQR, and individual dots represent participants’ data points.

Neural Data: Power spectral density (PSD)

Spectral analysis of the EEG focused on frequency bands with observed peaks in the PSD which indicates periodic oscillations: Alpha power and Beta power (Fig. 6A). The averaged alpha-power peak between 7-13 Hz and beta-power peak between 16-22 Hz were calculated across participants and focused on predefined clusters of electrodes marked with white circles in Fig. 6B. For each participant, we determined the alpha-power\beta-power peak as the frequency with the highest average amplitude within their frequency range and across segments in different conditions (quiet, continuous, intermittent) and in different level of interest (high or low).

A Full spectrum (2–30 Hz) averaged across all participants. Shaded areas around waveforms represent the SEM. B Topographical distribution of the averaged alpha-power peak and the averaged beta-power peak, with the clusters of central-partial and frontal-central electrodes marked with white circles, respectively. C Box plots showing the distribution of maximum mean alpha power (top) and beta power (bottom) across high and low interest conditions. Red lines indicate the median, boxes represent the IQR, whiskers extend to 1.5×IQR, and individual dots represent participants’ data points.

Repeated-measured ANOVA revealed no main effect of noise condition in either band [Alpha-power: F(2,31) = 1.166, p = 0.318; Beta-power: F(2,31) = 1, p = 0.373; Table 1]. However, power in both frequency bands was significantly modulated by situational interest with higher alpha-power and lower beta-power in the low vs. high interest conditions [Alpha-power: t(31) = -2.29, p = 0.029, Cohen’s d = 0.40; Beta-power: t(31) = 2.39, p = 0.023, Cohen’s d = 0.42; Table 1, Fig. 6C].

Discussion

Here we studied how behavioral and neurophysiological metrics associated with arousal, attention and speech processing vary while watching a frontal lecture, as a function of its varying levels of situational interest and the presence of external noise. Several neurophysiological responses were modulated by interest level, with portions of the lecture rated as less interesting associated with poorer neural speech tracking, higher skin-conductance levels, higher alpha-power, lower beta-power and a trend towards poorer performance on answering comprehension questions. Interestingly, level of interest had a more substantial effect on neurophysiological responses relative to background noise, which did not show significant effects on alpha- or beta-oscillations or on behavioral performance, and had a limited (and somewhat inconsistent) effects on skin-conductance and on neural speech-tracking. This was somewhat surprising, given the vast literature on the disruptive effect of background noise on speech processing, albeit under less ecological circumstances. These results highlight the importance of considering content-related factors when studying natural speech processing, which in this case had a more prominent effect on neural encoding of speech and listeners’ neurophysiological state than external noise.

That people have an easier time paying attention when they are interested is one of the cornerstones of modern pedagogy. Educators have long observed that students who find a topic engaging exhibit greater focus, motivation, and improved learning outcomes44. This principle has been repeatedly demonstrated in behavioral studies, showing that interest enhances memory, attention, and cognitive processing10,43,48. For instance, studies on reading comprehension show that individuals remember and understand texts better when they find them interesting45. Similarly, when students perceive a lecture or task as engaging, they persist longer and maintain focus, even when it is cognitively demanding59. Here we relied on group-level ratings of interest to capture variations in situational interest, across segments of the presented lecture, which likely stem from features of the lecture itself, such as presentation style, clarity, and content delivery. Ratings were highly consistent both within and across two independent cohorts (online- screening and lab study), indicating that they reliably capture common fluctuations in interest levels, above and beyond variance between individuals due to personal preferences or context44,51. This approach was further reinforced by content-analysis of the lecture, as lecture-segments that were rated as “highly interesting” often included concrete examples, clear visuals, or relatable content that invited reflection or emotional engagement. In contrast, lower-rated segments tended to be repetitive or abstract, lacking novelty or practical application. Our choice to study situational interest is motivated by its affordance for drawing generalizable group-level conclusions about the impact of interest on speech processing, and potential implication for teaching styles and pedagogical design. However, we acknowledge that this approach limits inferences on variability in interest levels across individuals, efforts that would require larger datasets and optimized designs for individual-level analyses.

Despite the extensive behavioral literature on interest, and its crucial role in human communication and learning, to date, little is known about its neurophysiological underpinnings. The scarcity of data is partially due to the conceptual difficulties in defining “interest”44,60, and partially due to the operational challenge of quantifying levels of interest and its predominant reliance on self-reported measures61,62,63. Nonetheless, some attempts have been made to advance our understanding of neural correlates of interest, particularly in learning contexts. In some real-life classroom studies, variations in the spectral profile of students’ EEG signal (e.g., in the delta, alpha and gamma band) were linked with different levels of interest during a lesson64,65, and curiosity-driven learning has been associated with modulation of dopaminergic reward circuits66,67. While these studies provide a proof-of-concept for the impact of interest on so-called “brain states”, they fall short of providing a comprehensive understanding of how interest impacts neural processing. In more controlled studies, fluctuations in situational interest are assessed through analysis of changes in inter-subject correlation of neural activity over time during the presentation of natural stimuli such as movies or audiobooks. In these studies, segments with higher inter-subject correlation values are associated with better ‘joint’ attention and engagement with stimulus material, which is also predictive of improved memory68,69,70,71,72,73. In a fMRI study, Song et al. 2021 linked fluctuations in engagement to activity in the default mode network and dorsal attention network activity, which also predicted memory encoding, reinforcing the connection between situational interest and attention.

The current data provides a more detailed mechanistic account for how situational interest may affect neural processing during learning. Interest modulated a multi-faceted neurophysiological “profile”—comprised of neural speech tracking, the periodic EEG spectrum and skin conductance—in a manner consistent with modulations observed more generally for attention to speech. Specifically, for segments rated as less interesting, there was reduced neural speech tracking of the lecturer’s speech, a pattern commonly found for impaired speech encoding74,75,76,77 and for speech that is not attended52,78,79,80,81. This result is seen both in the decoding analysis, which reflects overall poorer reconstruction accuracy of the speech in the low-interest vs. high-interest condition, as well as in the magnitude of the TRF response, particularly in the early time windows associated with more sensory levels of processing38,53,82,83. This effect directly links the construct of “interest” to the way the speech-content is processed in the brain, which may underlie the well-documented behavioral consequences of reduced interest on learning outcomes10,43,44,48.

Alongside the direct impact on speech processing, interest level was also associated with changes in global brain dynamics, as captured by the periodic EEG spectrum. Segments with low levels of interest were associated with higher alpha-power and with lower beta-power relative to high-interest segments. This pattern is consistent with the hypothesized role of these ongoing oscillations in attention and cognitive effort. Alpha oscillations are the most dominant feature of the EEG signal, and enhanced alpha is often associated with reduced attention to external stimuli and increased mind-wandering84,85,86,87,88,89,90. We must note, however, that alpha-oscillations are not monolithic, and in some cases alpha oscillations have been shown to support active attention by suppressing distracting input and maintaining selective focus, particularly in noisy or effortful listening conditions54,91. Nonetheless, the current finding of increased alpha-power in low-interest segments is in line with many studies, particularly in the neuroeducation domain, pointing to it as a signature for reduced engagement with presented content and learning activities92,93,94,95,96. The enhanced alpha-power in low-interest segments was accompanied by reduced beta-power, which is often noted as involved in processes such as cognitive control, predictive processing, and reward mechanisms56,97,98,99,100, following the notion that interest and motivation can shape auditory attention in a top-down manner101,102. In the context of speech comprehension, beta oscillations have been associated with the integration of auditory input into meaningful linguistic content, supporting active engagement with speech and improving comprehension56,100,103,104,105. These findings align well with the current results, where ostensibly segments of the lecture that were more interesting evoked these beta-related processes more extensively relative to low-interest segments. They are also in line with observations that beta activity declines when attention wanes or when listeners adopt a more passive, bottom-up processing mode57,106 as well as when listeners do not expect the content to be particularly meaningful or rewarding.

The effect of interest on neural activity was accompanied by physiological effects, as indicated by changes to phasic and tonic skin-conductance levels. Skin conductance is a well-established measure of autonomic arousal controlled by the sympathetic nervous system107,108. There is a strong established relationship between arousal and level of engagement, with levels of arousal generally associated with higher level of engagement and better performance109,110, although this relationship is not linear and sometimes follows an inverted U-shape whereby hyper-arousal levels actually accompany poorer performance27,111. Initially, we had expected to find higher levels of arousal in the high-interest conditions, which could reflect higher engagement with the lecture. However, the current results show the opposite effect with higher skin-conductance found during low-interest segments. One possible interpretation for this pattern is that here, skin-conductance levels reflect the investment of listening effort rather than arousal per-se55,112. In other words, when listeners find the content boring, but are still required to pay attention, they may exert additional effort to stay focused, leading to heightened physiological arousal despite reduced intrinsic motivation113,114,115. This compensatory perspective could, in part, explain the relatively small behavioral effect found here, with a marginally significant trend towards reduced performance in the low vs. high interest segments.

Taken together, the current findings demonstrate that momentary fluctuations in situational interest are accompanied by measurable changes in specific neural processes that are crucial for speech processing. The overall similarity between the profile of neurophysiological effects observed here and in more traditional studied of attention suggest that the constructs of ‘interest’ and ‘attention’ are highly intertwined and share common underlying mechanisms. This highlights the central importance of including listener-based factors such as interest in models of speech processing, particularly in realistic ecological contexts, acknowledging that the human brain exercises active selection of the information it chooses to process, based on its relevance and reward to the listener. Nonetheless, several unresolved issues from this study require additional follow-up research. These include the modest behavioral effect of interest level relative to the observed neurophysiological effect, as well as clarifying the role of arousal as reflecting increased interest or mitigating and compensative for the effects of boredom.

The second factor tested here was the effect of background construction noise on listeners during a realistic lecture, as part of our attempt to advance the ecological validity of speech-in-noise studies12,14,116,117,118,119. Our choice to compare continuous vs. intermittent sounds (continuous drilling vs. intermittent air-hammers) was motivated by competing hypotheses regarding the role of temporal structure in speech in noise processing, as discussed at length by Levy et al.9. One possibility is that continuous noise is more disruptive to listening, due to its constant level of acoustic masking, whereas for intermittent noise in is possible to ‘listen in the gaps’ and recover the masked speech information9,120,121,122,123,124,125. Alternatively, the ‘habituation hypothesis’ posits that monotonic nature of continuous noise may render it more prone to habituation, making it less disruptive126, whereas the frequent onsets and offsets of intermittent noise may trigger repeated phase-resets of cortical and arousal responses127,128, ultimately reducing cortical adaptation and leading to greater disruption of speech processing. In a previous study, where we studied the effect of these background noises during learning in a virtual reality classroom, we found that intermittent noise was more disruptive of performance, reduced the neural speech tracking of the teacher, and was accompanied by an increase in skin-conductance reflecting heightened arousal, relative to continuous noise9. Those findings were taken as supporting the ‘habituation hypothesis’, suggesting that despite the more substantial acoustic masking of continuous noise, it is less disruptive to speech processing, potentially due to habituation over time129,130. The current results are broadly in line with those findings, as here too we found that neural speech tracking was reduced and skin-conductance were elevated for intermittent vs. continuous construction noise, consistent with heightened arousal or increased listening effort in this condition112,113.

Interestingly, in both the current study and our previous work, the presence of background noise did not affect ongoing oscillatory activity in the alpha or beta ranges. This is in contrast to interest level which here showed a clear modulatory effect on these neural dynamics, as discussed above. Given the hypothesized functional roles of alpha- and beta-oscillations in attention and cognitive processing, this replicated null-result is noteworthy, as it suggests that the impact of a noisy background on speech processing on listeners may be qualitatively different than that of reduced attention or engagement with the lecture. As discussed by Levy et al.9, mixed results have been reported regarding the modulation of oscillatory activity in speech in noise studies, particularly in the alpha-band, with some reporting increased activity in noisy conditions91,131, some finding decreased activity132,133, and some reporting effect that vary as a function of noise-type or performance97,134. Overall, we can conclude that although alpha and beta oscillation can play important roles in perception and attention, they do not constitute monolithic neural markers of specific cognitive processes but rather capture global changes in neural dynamics that can arise from the interaction between stimulus features (e.g. noise), internal goals and cognitive demands87,98,135,136,137.

More broadly, when comparing the effects of noise and interest-level on the neurophysiological profile of responses, the current results show internal consistency in that conditions that both noise and low interest level were associated with reduced neural tracking of the lecture and with increased arousal. At the same time, the magnitude of effects was larger for interest levels and, as discussed here, also included modulation of alpha- and beta-oscillations. This pattern suggests that internal factors, such as top-down attention or interest in the content, may ultimately play a more central role in the way that listeners process and comprehend speech, than external acoustic interference. We put forth this hypothesis for testing in future studies.

To summarize, the current study contributes to endeavors to enhance the ecological validity of speech processing research and identify the neurophysiological underpinnings of fluctuations in attention and engagement to a continuous narrative over time. By demonstrating that fluctuations in situational interest-levels over time are intrinsic to naturalistic speech, and comparing the effects of interest-level and external noise on neurophysiological measure associated with arousal, attention and speech processing, this work advances current thinking about how environmental and internal factors influence neural processing in real-life. Results converge with previous research to emphasize the multi-faceted neurophysiological ‘profile’ of responses that are modulated by listener engagement and by the presence of background noise, indicating that no single metric is sufficient for capturing the mechanistic underpinnings of real-life speech processing. This work focuses on a specific commonplace example that requires sustained attention to speech—watching a video of an educational lecture. While we acknowledge that this context lacks many aspects of live learning environments, such as interactive instruction and social interactions138,139, it still captures a form of learning that has become a staple of modern education, particularly since the COVID-19 pandemic. This work, together with previous studies using video or virtual reality-based learning9,96,140,141,142,143,144 lay the foundation for future studies investigating neurophysiological features of attention and speech processing in live learning contexts, an exciting emerging research field95,140,145,146. Another limitation of the current results is that the neurophysiological metrics used here (e.g., speech tracking, spectral power and skin-conductance) lack sufficient sensitivity for quantifying fluctuations on a moment-by-moment basis, but require averaging data across large portions of the experiment. This is due to their relatively poor signal to noise and non-specific nature147. Our hope is that future advances in signal processing techniques will improve and validate the single-trial reliability of these metrics, which would provide much needed insight into the temporal dynamics of attention to speech and the nature of its fluctuations over time.

Methods

Participants

Data was collected from 32 adult volunteers (20 female, 12 male), ranging in age between 19 and 28 (M = 23.54, SD = ± 1.97). Sample size was determined based on results from a similar previous study in our lab9, where we found that a sample of at least N = 28 is required to detect within-group effect sizes of Cohen’s d = 0.55 with a two-sided α = 0.05, and power of 0.8. All participants were fluent Hebrew speakers with self-reported normal hearing and no history of psychiatric or neurological disorders. The study was approved by the Institutional review board of Bar Ilan University (approval # ISU202106003), and participants gave their written informed consent prior to the experiment. Participants were either paid or received course credit for participating in the experiment.

Stimuli

The stimuli consisted of a 35-minutes video recording of a public lecture, given by Prof. Liat Ayalon on the topic of Ageism. As shown in Fig. 7, the video recording included the lecturer herself as well as the slides accompanying the talk. Prof. Ayalon gave her approval to use these materials for research purposes.

For the noise stimuli, we used recordings from a real-life construction site (recorded using a mobile phone; iPhone 12). The continuous noise was a 1-minute-long recording of drilling, and the intermittent noise was a 1 min-long recording of air hammers (see Fig. 7). The continuous and intermittent noise stimuli were equated in loudness to each other.

Online stimulus screening study

The lecture materials were pre-screened in an online study conducted using the webservice Qualtrics (Provo, UT; https://www.qualtrics.com). 37 adult volunteers (29 female, eight male), ranging in age between 20 and 29 (M = 22.54, SD = ± 1.76), participated in the screening study. Participants watched the lecture on their phone or computer in a quiet environment. As in the main experiment, the lecture was presented continuously, but was split into in 63 segments ranging from 23 to 40 s each (M = 32.6, SD = ± 4.2). After each segment participants were asked to rate their level of interest in the segment, on a scale from 1 to 7 (“How interesting was this segment?”; 1- not at all, 7- extremely)63,148. To ensure that participants were indeed paying attention to the lecture, after every 20–23 segments, participants were asked to answer ten multiple-choice questions about the recent content of the lecture. Participants who achieved less than 70% correct were excluded from analysis of the screening study. In the screening study no noises were added to the lecture segments, and served as a baseline for testing whether adding noise in the main experiment affected ratings of interest. They were also used to ensure that the lecture-segments allocated to different noise conditions in the main experiment did not vary significantly in their interest-level ratings.

Main Experiment

The experiment was programmed and presented using OpenSesame (version: 3.3.14 https://osdoc.cogsci.nl149). Participants were seated on a comfortable chair in a sound attenuated booth and were instructed to keep as still as possible and blink and breathe naturally. The video of the lecture was presented on a computer monitor in front of the participants, and the lecture audio was presented through a loudspeaker placed behind the monitor.

The lecture was presented continuously, but was split into 63 segments ranging from 23 to 40 seconds each (M = 32.6, SD = ± 4.2). The varied lengths were necessary to ensure that the segments did not cut-off the lecture mid-sentence or mid-thought. This duration provided participants with enough time to engage with the content, while also being suitable for our analyses (e.g., TRF), and allowing for a sufficient number of data points to assess behavioral and self-reported measures of interest throughout the experiment.

Each segment was randomly assigned to one of three conditions: 1) quiet (21 trials); 2) continuous noise (21 trials); 3) intermittent noise (20 trials). In the two noise conditions, continuous/intermittent noise was presented alongside the lecture, at a loudness level of 0.2 (-16 dB) relative to the lecture. The allocation of segments to the different noise condition was kept constant across participants. We verified that the segments assigned to different noise-conditions did not differ on average in their level of interest, based on results from the online screening study [mean interest levels in the screening study for the segments later assigned to each condition: quiet: 4.25, continuous: 4.3, intermittent: 4.31; F(2,19) = 0.044, p = 0.957].

After each segment, participants were asked to rate their level of interest on a scale from 1 to 7 (“How interesting was this segment?”; 1- not at all, 7- extremely). In addition, after every 3 segments, participants were asked to answer three comprehension multiple-choice questions, regarding the content of the last three segments of the lecture they heard to ensure that they were paying attention and to assess their level of understanding/memory of the lecture content (one question per segment; see Fig. 7). Participants received feedback regarding the correctness of their answers. Participants indicated via button press when they were ready to continue to the next trial. A training trial was performed at the beginning of the experiment (quiet condition), to familiarize participants with the task and this trial was excluded from data analysis.

EEG and GSR data recordings

Electroencephalography (EEG) was recorded using a 64 Active-Two system (BioSemi B.V., Amsterdam, Netherlands; sampling rate: 1024 Hz) with Ag-AgCl electrodes, placed according to the 10–20 system. Two external electrodes were placed on the mastoids and served as reference channels. Electrooculographic signals were simultaneously measured by 3 additional electrodes, located above the right eye and on the external side of both eyes. Galvanic Skin Response (GSR), which captures changes in the electrical properties of the skin due to changes in sweat levels and is considered an index of the autonomic nerve responses, was measured using 2 passive Nihon Kohden electrodes placed on the fingertips of the index and middle fingers of participants’ nondominant hand. The signal was recorded through the BioSemi system amplifier and was synchronized to the sampling rate of the EEG.

Behavioral data analysis

Behavioral data consisted of accuracy on the comprehension questions asked about each segment and subjective rating of interest. These values were averaged across lecture segments, separately for each noise-condition (quiet, continuous, and intermittent), and for each participant. A one-way repeated-measures ANOVA was performed using JASP (version: 0.17.3; JASP Team, 2025; https://jasp-stats.org/), to test whether interest-ratings and/or accuracy on the comprehension questions differed significantly across noise-conditions.

In addition, we identified the median interest-level value across all lecture-segments and used it to classify each lecture-segments as high-interest vs. low-interest. We then performed a paired t-test to evaluate whether comprehension-question accuracy different for segments with high vs. low interest level ratings.

GSR data analysis

The GSR data were analyzed using the Ledalab MATLAB toolbox150 (version: Ledalab V3.4.9; http://www.ledalab.de) as well as custom written scripts. The data were downsampled to 16 Hz, as per the toolbox recommendation. The raw data were manually inspected for distinguishable artifacts, which were fixed using a built-in linear interpolation. We performed a continuous decomposition analysis (CDA) on the entire GSR signal, and then segmented it into trials. The CDA estimates and separates the continuous phasic and tonic activity using a standard deconvolution. Initially, 4 metrics were extracted for each trial: (1) the mean tonic activity across the entire trial (2) the mean phasic response, (3) the number of phasic skin conductance responses (nSCR), defined as transient changes in the phasic response that exceed a threshold of 0.01 micro-siemens (muS); and (4) the sum of SCR amplitudes, estimated as the area under the curve of the phasic response around SCR peaks (SCR-amp). Since the nSCR and SCR-amp measures showed highly similar patterns to the mean phasic activity and did not provide additional insights, only the mean phasic and mean tonic activity were used in subsequent analyses. For each participant, these metrics were averaged across trials within each condition. We used a 1-way ANOVA with repeated measures to test whether any of these measures were significantly affected by the different noise conditions or by the level of interest (high or low) as mentioned above. To further examine the effects of noise, we conducted planned a priori paired t-tests, following the same logic as in our previous study9: (1) comparing the two noise conditions (continuous and intermittent) vs. the quiet condition, to evaluate the overall effect of noise, and (2) comparing between the two noise conditions (continuous vs. intermittent).

EEG Preprocessing

EEG preprocessing and analysis were performed using FieldTrip (version: 20220729; https://www.fieldtriptoolbox.org)151), a matlab-based toolbox as well as custom written scripts. Raw data was re-referenced to the linked left and right mastoids and bandpass filtered between 0.5-40 Hz using a zero-phase, two-pass Butterworth IIR filter to reduce artifacts with extreme high-frequency activity or low-frequency activity/drifts. The filtered data was visually inspected and gross artifacts exceeding ±50 μV (that were not eye-movements) were removed manually. Entire trials containing such artifacts were excluded from further analysis, with 1–4 trials rejected per participant (M = 0.875, SD = 1.21). Independent component analysis (ICA) was performed using the ft_componentanalysis function (method = ‘runica’) to identify and remove components associated with horizontal or vertical eye-movements as well as heartbeats (based on visual inspection; 4–10 components were removed), with the inclusion of electrooculographic channels to improve the algorithm’s identification of eye-movement artifacts. Any remaining noisy electrodes, likely due to bad or loose connectivity, were replaced with the weighted average of their neighbors using an interpolation procedure (either on the entire data set or on a per-trial basis, as needed), with up to two electrodes interpolated per participant.

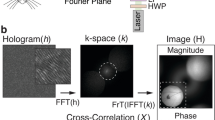

Neural speech tracking analysis

The clean data was segmented into trials, and the first 420 ms of each trial were removed to avoid onset effects. To estimate the neural response to the speaker in the different noise scenarios we performed speech tracking analysis, using both an encoding and a decoding approach. We estimated linear TRFs using the mTRF MATLAB toolbox152, which constitutes a linear transfer function describing the relationship between a particular feature of the stimulus (S) and the neural response (R) recorded when hearing it.

The S used here was the speech-envelope stimulus presented in each trial, which was extracted using an equally spaced filterbank between 100-10,000 Hz based on Liberman’s cochlear frequency map153. The narrowband filtered signals were summed across bands after taking the absolute value of the Hilbert transform for each one, resulting in a broadband envelope signal. The R used here was the continuous EEG data, after ICA for correcting eye-movements, and bandpass filtered between 0.8 and 20 Hz using a zero-phase, two-pass Butterworth IIR filter. S and R were aligned in time and were downsampled to 100 Hz for computational efficiency. Encoding and decoding models were run and optimized separately for each noise-condition (quiet, continuous and intermittent). Encoding TRFs were calculated over time lags ranging from −150 (pre-stimulus) to 1000 ms, and the decoding analysis used time lags of 0 to 400 ms.

A leave-one-out cross validation protocol was used to assess the TRF predictive power. In each iteration, 61 trials are selected to train the model (train set), which was then used to predict either the neural response at each electrode (encoding) or the speech envelope (decoding) in the left-out trial (test set). The goodness of fit (predictive power) of the encoding model was determined by calculating the Pearson correlation between the predicted and actual neural response at each sensor. Similarly, the goodness of fit of the decoding model was determined by calculating the Pearson correlation between the predicted and actual speech envelope. To prevent overfitting of the model, a ridge parameter was chosen as part of the cross-validation process (λ -predictive power). This parameter significantly influences the shape and amplitude of the TRF and therefore, rather than choosing a different λ for each participant (which would limit group-level analyses, especially for the encoding approach), a common λ value was selected for all participants. Specifically, we tested a range of λ values (from 10-3 to 106) and selected the λ that yielded the highest average predictive power across participants, electrodes and conditions. In this dataset, the optimal ridge parameter was λ = 1000 for both the encoding and decoding models.

To determine which subset of sensors showed a significant speech tracking response (encoding approach) we used a permutation test, where we shuffled the pairing between acoustic envelope (S) and neural data responses (R) across trials such that speech-envelopes presented in one trial were paired with the neural response recorded in a different trial. This procedure was repeated 100 times and an encoding model was estimated for each permutation. We obtained a “max-chance predictive power” null-distribution by selecting the maximum r-value from the grand average across participants for each permutation. EEG channels with predictive power values with the top 5% of the null distribution were deemed to exhibit a significant speech tracking response. All subsequent TRF and predictive power analyses were limited to this subset of electrodes, with ensured that comparisons between condition were conducted only on electrodes where speech-tracking estimates are interpretable and meaningful.

Next, we tested for differences in the speech tracking response (TRF) and its predictive power across the conditions. To assess whether speech tracking was affected by the presence of any type of noise, we compared responses in the quiet condition vs. noise condition (average across the two noise conditions - continuous and intermittent). To test whether the TRFs were affected by the specific type of noise, we further compared TRFs in the continuous vs. intermittent condition. In addition, we estimated TRFs separately for the speech-segments rated as ‘high’ and ‘low’ interest levels and compared whether the speech tracking was affected by subjective interest ratings. In all analyses we performed paired t-tests at each electrode and each time point for TRF comparisons and corrected for multiple comparisons using spatio-temporal clustering.

EEG Spectral analysis

The second type of analysis performed on the EEG data was spectral analysis, which focused on two frequency bands with observed peaks in the PSD indicates periodic oscillations: Alpha (7–13 Hz), and Beta (16–22 Hz). The range we focus on in each frequency chosen according to the window surrounding the peaks observed in the PSD. This analysis was performed on the clean EEG data, across segments (same segmentation as used for the speech-tracking analysis). We calculated the EEG Power Spectral Density (PSD) of individual segments using the multitaper fast-fourier transform method with Hanning tapers (method ‘mtmfft’ in the fieldtrip toolbox). The PSDs were averaged across segments for each participant, separately for each electrode, across noise conditions (quiet, continuous, intermittent) and across level of interest (high or low). We then used the Fitting Oscillations and One-Over-F algorithm (FOOOF154) to decompose the PSD into periodic (oscillatory) and aperiodic components. The periodic portion of the PSD was used to extract power-estimations for the specific frequency bands.

For each participant, we identified the frequency with the largest amplitude within the alpha range (7–13 Hz) and beta range (16–22 Hz), the only two bands where clear periodic activity was observed, and averaged the response across a cluster of electrodes (21 for alpha, 29 for beta) showing the strongest activity in the grand-averaged power topography, as determined by visual inspection across all participants and conditions. The average power in each band was compared across conditions (quiet, continuous, intermittent) using 1-way ANOVA with repeated measures, and across level of interest (high or low) using paired t-test.

Data availability

Data and code have been deposited on the Open Science Framework and are publicly available at: https://osf.io/z5naf/.

Code availability

Data and code have been deposited on the Open Science Framework and are publicly available at: https://osf.io/z5naf/.

References

Smallwood, J. et al. Subjective experience and the attentional lapse: task engagement and disengagement during sustained attention. Conscious Cogn. 13, 657–690 (2004).

Martin, D. & Miller, C. Speech and Language Difficulties in the Classroom. (David Fulton Publishers, 2012).

Esterman, M. & Rothlein, D. Models of sustained attention. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 29, 174–180 (2019).

Farley, J., Risko, E. F. & Kingstone, A. Everyday attention and lecture retention: the effects of time, fidgeting, and mind wandering. Front Psychol. 4, 619 (2013).

Bhandari, P., Demberg, V. & Kray, J. Predictability effects in degraded speech comprehension are reduced as a function of attention. Lang. Cogn. 14, 534–551 (2022).

Billings, C. J., Olsen, T. M., Charney, L., Madsen, B. M. & Holmes, C. E. Speech-in-noise testing: an introduction for audiologists. Semin Hear 45, 55–82 (2023).

Ljung, R., Sörqvist, P., Kjellberg, A. & Green, A. M. Poor listening conditions impair memory for intelligible lectures: implications for acoustic classroom standards. Build. Acoust. 16, 257–265 (2009).

Kujala, T. & Brattico, E. Detrimental noise effects on brain’s speech functions. Biol. Psychol. 81, 135–143 (2009).

Levy, O., Korisky, A., Zvilichovsky, Y. & Zion Golumbic, E. The neurophysiological costs of learning in a noisy classroom: an ecological virtual reality study. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 37, 300–316 (2025).

Ainley, M., Hidi, S. & Berndorff, D. Interest, learning, and the psychological processes that mediate their relationship. J. Educ. Psychol. 94, 545–561 (2002).

Pounder, J. Quality teaching through transformational classroom leadership. Qual. Assur. Educ. 22, 273–285 (2014).

Darwin, C. J. Listening to speech in the presence of other sounds. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 363, 1011–1021 (2008).

Eckert, M. A., Teubner-Rhodes, S. & Vaden, K. I. Is listening in noise worth it? The neurobiology of speech recognition in challenging listening conditions. Ear Hear 37, 101S–110S (2016).

Peelle, J. E. Listening effort: how the cognitive consequences of acoustic challenge are reflected in brain and behavior. Ear Hear 39, 204–214 (2018).

Trimmel, K., Schätzer, J. & Trimmel, M. Acoustic noise alters selective attention processes as indicated by direct current (DC) brain potential changes. Int J. Environ. Res Public Health 11, 9938–9952 (2014).

Dimitrijevic, A., Smith, M. L., Kadis, D. S. & Moore, D. R. Neural indices of listening effort in noisy environments. Sci. Rep. 9, 11278 (2019).

Kong, Y. Y., Somarowthu, A. & Ding, N. Effects of spectral degradation on attentional modulation of cortical auditory responses to continuous speech. J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 16, 783–796 (2015).

Alvarsson, J. J., Wiens, S. & Nilsson, M. E. Stress recovery during exposure to nature sound and environmental noise. Int J. Environ. Res. Public Health 7, 1036–1046 (2010).

Mackersie, C. L. & Cones, H. Subjective and psychophysiological indexes of listening effort in a competing-talker task. J. Am. Acad. Audio. 22, 113–122 (2011).

Zou, J. et al. Auditory and language contributions to neural encoding of speech features in noisy environments. Neuroimage 192, 66–75 (2019).

Wöstmann, M., Herrmann, B., Wilsch, A. & Obleser, J. Neural alpha dynamics in younger and older listeners reflect acoustic challenges and predictive benefits. J. Neurosci. 35, 1458–1467 (2015).

Helps, S. K., Bamford, S., Sonuga-Barke, E. J. S. & Söderlund, G. B. W. Different effects of adding white noise on cognitive performance of sub-, normal and super-attentive school children. PLoS One 9, e112768 (2014).

Maamor, N. & Billings, C. J. Cortical signal-in-noise coding varies by noise type, signal-to-noise ratio, age, and hearing status. Neurosci. Lett. 636, 258–264 (2017).

Hopkins, K. & Moore, B. C. J. The contribution of temporal fine structure to the intelligibility of speech in steady and modulated noise. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 125, 442–446 (2009).

Rosen, S., Souza, P., Ekelund, C. & Majeed, A. A. Listening to speech in a background of other talkers: effects of talker number and noise vocoding. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 133, 2431 (2013).

Tegelbeckers, J. et al. Task-irrelevant novel sounds improve attentional performance in children with and without ADHD. Front Psychol. 6, 167183 (2016).

Beerendonk, L. et al. A disinhibitory circuit mechanism explains a general principle of peak performance during mid-level arousal. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2312898121 (2024).

Yasmin, S., Irsik, V. C., Johnsrude, I. S. & Herrmann, B. The effects of speech masking on neural tracking of acoustic and semantic features of natural speech. Neuropsychologia 186, 108584 (2023).

Herrmann, B. Enhanced neural speech tracking through noise indicates stochastic resonance in humans. Elife 13, RP100830 (2025).

Ratelle, D. & Tremblay, P. Neural tracking of continuous speech in adverse acoustic conditions among healthy adults with normal hearing and hearing loss: A systematic review. Hear Res. 466, 109367 (2025).

Söderlund, G., Sikström, S. & Smart, A. Listen to the noise: noise is beneficial for cognitive performance in ADHD. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 48, 840–847 (2007).

Sikström, S. & Söderlund, G. Stimulus-dependent dopamine release in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Psychol. Rev. 114, 1047–1075 (2007).

Sikström, S. & Söderlund, G. Positive effects of noise on cognitive performance: explaining the moderate brain arousal model. In The 9th Congress of the International Commission on the Biological Effects of Noise (ICBEN), 378–386. https://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:su:diva-34780 (2008).

Sonkusare, S., Breakspear, M. & Guo, C. Naturalistic stimuli in neuroscience: critically acclaimed. Trends Cogn. Sci. 23, 699–714 (2019).

Shamay-Tsoory, S. G. & Mendelsohn, A. Real-life neuroscience: an ecological approach to brain and behavior research. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 14, 841–859 (2019).

Mealings, K., Miles, K. & Buchholz, J. M. A methodological review of stimuli used for classroom speech-in-noise tests. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 67, 4850–4866 (2024).

Hamilton, L. S. & Huth, A. G. The revolution will not be controlled: natural stimuli in speech neuroscience. Lang. Cogn. Neurosci. 35, 573–582 (2020).

Kurthen, I. et al. Selective attention modulates neural envelope tracking of informationally masked speech in healthy older adults. Hum. Brain Mapp. 42, 3042–3057 (2021).

Agmon, G., Jaeger, M., Tsarfaty, R., Bleichner, M. G. & Golumbic, E. Z. “Um…, It’s Really Difficult to… Um… Speak Fluently”: neural tracking of spontaneous speech. Neurobiol. Lang. 4, 435–454 (2023).

Agmon, G. et al. Challenges and methods in annotating natural speech for neurolinguistic research. Neurobiol. Lang. 6, e12 (2025).

Hollis, R. B. & Was, C. A. Mind wandering, control failures, and social media distractions in online learning. Learn Instr. 42, 104–112 (2016).

Hefter, M. H. & Nitsch, H. Synchronous distance learning: effects of interest and achievement goals on police students’ learning engagement and outcomes. Educ. Sci. 14, 118 (2024).

Schiefele, U. Interest, learning, and motivation. Educ. Psychol. 26, 299–323 (1991).

Ann Renninger, K. & Hidi, S. The Power of Interest for Motivation and Engagement. (Routledge, 2016)

Schraw, G., Flowerday, T. & Lehman, S. Increasing situational interest in the classroom. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 13, 211–224 (2001).

Golke, S. & Wittwer, J. Informative narratives increase students’ situational interest in science topics. Learn Instr. 93, 101973 (2024).

Drymiotou, I., Constantinou, C. P. & Avraamidou, L. Enhancing students’ interest in science and understandings of STEM careers: the role of career-based scenarios. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 43, 717–736 (2021).

Hidi, S. Interest: a unique motivational variable. Educ. Res Rev. 1, 69–82 (2006).

Roure, C., Lentillon-Kaestner, V. & Pasco, D. Students’ individual interest in physical education: development and validation of a questionnaire. Scand. J. Psychol. 62, 64–73 (2021).

Ann Renninger, K. Individual interest and its implications for understanding intrinsic motivation. In Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation (eds. Sansone, C. & Harackiewicz, J. M.), 373–404 (Academic Press, 2000).

Roure, C. & Lentillon-Kaestner, V. Relationships between students’ individual interest, achievement goals, perceived competence and situational interest: A Cluster analysis in swimming. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 28, 322–340 (2022).

Broderick, M. P., Anderson, A. J., Di Liberto, G. M., Crosse, M. J. & Lalor, E. C. Electrophysiological correlates of semantic dissimilarity reflect the comprehension of natural, narrative speech. Curr. Biol. 28, 803–809 (2018).

Karunathilake, I. M. D., Kulasingham, J. P. & Simon, J. Z. Neural tracking measures of speech intelligibility: manipulating intelligibility while keeping acoustics unchanged. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2309166120 (2023).

Wöstmann, M., Lim, S. J. & Obleser, J. The human neural alpha response to speech is a proxy of attentional control. Cereb. Cortex 27, 3307–3317 (2017).

Howells, F. M., Stein, D. J. & Russell, V. A. Perceived mental effort correlates with changes in tonic arousal during attentional tasks. Behav. Brain Funct. 6, 39 (2010).

Weiss, S. & Mueller, H. M. Too many betas do not spoil the broth’: the role of beta brain oscillations in language processing. Front. Psychol. 3, 201 (2012).

Gao, Y. et al. Selective attention enhances beta-band cortical oscillation to speech under “cocktail-party” listening conditions. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 11, 34 (2017).

Rahma, O. et al. Electrodermal activity for measuring cognitive and emotional stress level. J. Med Signals Sens 12, 155–162 (2022).

Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., Titz, W. & Perry, R. P. Academic emotions in students’ self-regulated learning and achievement: a program of qualitative and quantitative research. Educ. Psychol. 37, 91–105 (2002).

Hidi, S. E. & Renninger, K. A. Interest development and its relation to curiosity: needed neuroscientific research. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 31, 833–852 (2019).

Greene, B. A. Measuring cognitive engagement with self-report scales: reflections from over 20 years of research. Educ. Psychol. 50, 14–30 (2015).

Rosenman, R., Tennekoon, V. & Hill, L. G. Measuring bias in self-reported data. Int J. Behav. Health. Res. 2, 320–332 (2011).

Busselle, R. & Bilandzic, H. Measuring narrative engagement. Media Psychol. 12, 321–347 (2009).

Othman, E. S., Faye, I. & Hussaan, A. M. Automatic clustering of students by level of situational interest based on their EEG features. Appl. Sci. 12, 389 (2022).

Babiker, A., Faye, I., Mumtaz, W., Malik, A. S. & Sato, H. EEG in classroom: EMD features to detect situational interest of students during learning. Multimed. Tools Appl. 78, 16261–16281 (2019).

Kang, M. J. et al. The wick in the candle of learning: epistemic curiosity activates reward circuitry and enhances memory. Psychol. Sci. 20, 963–973 (2009).

Gruber, M. J., Gelman, B. D. & Ranganath, C. States of curiosity modulate hippocampus-dependent learning via the dopaminergic circuit. Neuron 84, 486–496 (2014).

Cohen, S. S. & Parra, L. C. Memorable audiovisual narratives synchronize sensory and supramodal neural responses. eNeuro 3, e0203–e0216 (2016).

Cohen, S. S., Henin, S. & Parra, L. C. Engaging narratives evoke similar neural activity and lead to similar time perception. Sci. Rep. 7, 4578 (2017).

Kaneshiro, B., Nguyen, D. T., Norcia, A. M., Dmochowski, J. P. & Berger, J. Inter-subject correlation of electroencephalographic and behavioural responses reflects time-varying engagement with natural music. Eur. J. Neurosci. 59, 3162–3183 (2024).

Madsen, J., Margulis, E. H., Simchy-Gross, R. & Parra, L. C. Music synchronizes brainwaves across listeners with strong effects of repetition, familiarity and training. Sci. Rep. 9, 3576 (2019).

Cohen, S. S. et al. Neural engagement with online educational videos predicts learning performance for individual students. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 155, 60–64 (2018).

Ki, J. J., Kelly, S. P. & Parra, L. C. Attention strongly modulates reliability of neural responses to naturalistic narrative stimuli. J. Neurosci. 36, 3092–3101 (2016).

Schmitt, R., Meyer, M. & Giroud, N. Better speech-in-noise comprehension is associated with enhanced neural speech tracking in older adults with hearing impairment. Cortex 151, 133–146 (2022).

Kries, J. et al. Exploring neural tracking of acoustic and linguistic speech representations in individuals with post-stroke aphasia. Hum. Brain Mapp. 45, e26676 (2024).

MacIntyre, A. D., Carlyon, R. P. & Goehring, T. Neural decoding of the speech envelope: effects of intelligibility and spectral degradation. Trends Hear 28, 23312165241266316 (2024).

Chen, Y. P. et al. Speech intelligibility changes the temporal evolution of neural speech tracking. Neuroimage 268, 119894 (2023).

Ding, N. & Simon, J. Z. Emergence of neural encoding of auditory objects while listening to competing speakers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 11854–11859 (2012).

Zion Golumbic, E. M. et al. Mechanisms underlying selective neuronal tracking of attended speech at a “Cocktail Party”. Neuron 77, 980–991 (2013).

Kaufman, M. & Zion Golumbic, E. Listening to two speakers: capacity and tradeoffs in neural speech tracking during Selective and Distributed Attention. Neuroimage 270, 119984 (2023).

Straetmans, L., Adiloglu, K. & Debener, S. Neural speech tracking and auditory attention decoding in everyday life. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 18, 1483024 (2024).

Brodbeck, C., Presacco, A. & Simon, J. Z. Neural source dynamics of brain responses to continuous stimuli: Speech processing from acoustics to comprehension. Neuroimage 172, 162–174 (2018).

Vanthornhout, J., Decruy, L. & Francart, T. Effect of task and attention on neural tracking of speech. Front. Neurosci. 13, 977 (2019).

Compton, R. J. et al. Effects of task context on EEG correlates of mind-wandering. Cogn. Affect Behav. Neurosci. 24, 72–86 (2024).

Compton, R. J., Gearinger, D. & Wild, H. The wandering mind oscillates: EEG alpha power is enhanced during moments of mind-wandering. Cogn. Affect Behav. Neurosci. 19, 1184–1191 (2019).

Arnau, S. et al. Inter-trial alpha power indicates mind wandering. Psychophysiology 57, e13581 (2020).

Klimesch, W. Alpha-band oscillations, attention, and controlled access to stored information. Trends Cogn. Sci. 16, 606–617 (2012).

Foxe, J. J. & Snyder, A. C. The role of alpha-band brain oscillations as a sensory suppression mechanism during selective attention. Front Psychol. 2, 154 (2011).

Magosso, E., De Crescenzio, F., Ricci, G., Piastra, S. & Ursino, M. EEG alpha power is modulated by attentional changes during cognitive tasks and virtual reality immersion. Comput Intell. Neurosci. 2019, 7051079 (2019).

Obleser, J., Wöstmann, M., Hellbernd, N., Wilsch, A. & Maess, B. Adverse listening conditions and memory load drive a common alpha oscillatory network. J. Neurosci. 32, 12376–12383 (2012).

Strauß, A., Wöstmann, M. & Obleser, J. Cortical alpha oscillations as a tool for auditory selective inhibition. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 8, 350 (2014).

Davidesco, I. et al. The Temporal dynamics of brain-to-brain synchrony between students and teachers predict learning outcomes. Psychol. Sci. 34, 633–643 (2023).

Dikker, S. et al. Brain-to-brain synchrony tracks real-world dynamic group interactions in the classroom. Curr. Biol. 27, 1375–1380 (2017).

Haegens, S., Händel, B. F. & Jensen, O. Top-down controlled alpha band activity in somatosensory areas determines behavioral performance in a discrimination task. J. Neurosci. 31, 5197–5204 (2011).

Grammer, J. K., Xu, K. & Lenartowicz, A. Effects of context on the neural correlates of attention in a college classroom. NPJ Sci. Learn 6, 15 (2021).

Davidesco, I., Glaser, N., Stevenson, I. H. & Dagan, O. Detecting fluctuations in student engagement and retention during video lectures using electroencephalography. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 54, 1895–1916 (2023).

Viswanathan, V., Bharadwaj, H. M., Heinz, M. G. & Shinn-Cunningham, B. G. Induced alpha and beta electroencephalographic rhythms covary with single-trial speech intelligibility in competition. Sci. Rep. 13, 10216 (2023).

Engel, A. K. & Fries, P. Beta-band oscillations-signalling the status quo? Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 20, 156–165 (2010).

Hoy, C. W. et al. Beta and theta oscillations track effort and previous reward in the human basal ganglia and prefrontal cortex during decision making. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2322869121 (2024).

Lewis, A. G. & Bastiaansen, M. A predictive coding framework for rapid neural dynamics during sentence-level language comprehension. Cortex 68, 155–168 (2015).

Mas-Herrero, E., Ripollés, P., HajiHosseini, A., Rodríguez-Fornells, A. & Marco-Pallarés, J. Beta oscillations and reward processing: Coupling oscillatory activity and hemodynamic responses. Neuroimage 119, 13–19 (2015).

Chikermane, M. et al. Cortical beta oscillations map to shared brain networks modulated by dopamine. Elife 13, RP97184 (2024).

Shahin, A. J., Picton, T. W. & Miller, L. M. Brain oscillations during semantic evaluation of speech. Brain Cogn. 70, 259–266 (2009).

Hovsepyan, S., Olasagasti, I. & Giraud, A. L. Rhythmic modulation of prediction errors: a top-down gating role for the beta-range in speech processing. PLoS Comput. Biol. 19, e1011595 (2023).

Arnal, L. H., Wyart, V. & Giraud, A. L. Transitions in neural oscillations reflect prediction errors generated in audiovisual speech. Nat. Neurosci. 14, 797–801 (2011).

Graber, E. & Fujioka, T. Induced beta power modulations during isochronous auditory beats reflect intentional anticipation before gradual tempo changes. Sci. Rep. 10, 4207 (2020).

Critchley, H. D. Electrodermal responses: what happens in the brain. Neuroscientist 8, 132–142 (2002).

Boucsein, W. Electrodermal Activity: Second Edition. (Springer, 2012).

Gellisch, M. et al. Interactive teaching enhances students’ physiological arousal during online learning. Ann. Anat. 247, 152050 (2023).

Puusepp, I. et al. Changes in physiological arousal during an arithmetic task: profiles of elementary school students and their associations with mindset, task performance and math grade. Sci. Rep. 14, 1606 (2024).

Paechter, M. et al. Learning in adverse circumstances: impaired by learning with anxiety, maladaptive cognitions, and emotions, but supported by self-concept and motivation. Front Psychol. 13, 850578 (2022).

Naccache, L. et al. Effortless control: executive attention and conscious feeling of mental effort are dissociable. Neuropsychologia 43, 1318–1328 (2005).

Mehler, B., Reimer, B. & Coughlin, J. F. Sensitivity of physiological measures for detecting systematic variations in cognitive demand from a working memory task: an on-road study across three age groups. Hum. Factors 54, 396–412 (2012).

Raffaelli, Q., Mills, C. & Christoff, K. The knowns and unknowns of boredom: a review of the literature. Exp. Brain Res. 236, 2451–2462 (2018).

McNeal, K. S. et al. Biosensors show promise as a measure of student engagement in a large introductory biology course. CBE Life Sci. Educ. 19, ar50 (2020).

Shavit-Cohen, K. & Zion Golumbic, E. The dynamics of attention shifts among concurrent speech in a naturalistic multi-speaker virtual environment. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 13, 386 (2019).

Mattys, S. L., Davis, M. H., Bradlow, A. R. & Scott, S. K. Speech recognition in adverse conditions: a review. Lang. Cogn. Process 27, 953–978 (2012).

Dubbelboer, F. & Houtgast, T. A detailed study on the effects of noise on speech intelligibility. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 122, 2865–2871 (2007).

Sala, E. & Rantala, L. Acoustics and activity noise in school classrooms in Finland. Appl. Acoust. 114, 252–259 (2016).

Cooke, M. A glimpsing model of speech perception in noise. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 119, 1562–1573 (2006).

Fogerty, D., Carter, B. L. & Healy, E. W. Glimpsing speech in temporally and spectro-temporally modulated noise. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 143, 3047–3057 (2018).

Howard-Jones, P. A. & Rosen, S. Uncomodulated glimpsing in ‘“checkerboard”’ noise. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 93, 2915–2922 (1993).

Füllgrabe, C., Berthommier, F. & Lorenzi, C. Masking release for consonant features in temporally fluctuating background noise. Hear Res. 211, 74–84 (2006).

Koelewijn, T., Zekveld, A. A., Festen, J. M. & Kramer, S. E. Pupil dilation uncovers extra listening effort in the presence of a single-talker masker. Ear Hear 33, 291–300 (2012).

Miller, G. A. & Licklider, J. C. R. The intelligibility of interrupted speech. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 22, 167–173 (1950).

Thompson, R. F. & Spencer, W. A. Habituation: a model phenomenon for the study of neuronal substrates of behavior. Psychol. Rev. 73, 16–43 (1966).

Ten Oever, S. et al. Low-frequency cortical oscillations entrain to subthreshold rhythmic auditory stimuli. J. Neurosci. 37, 4903–4912 (2017).

Doelling, K. B., Florencia Assaneo, M., Bevilacqua, D., Pesaran, B. & Poeppel, D. An oscillator model better predicts cortical entrainment to music. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 116, 10113–10121 (2019).

Marrufo-Pérez, M. I., Lopez-Poveda, E. A. & Marrufo-P Erez, M. I. Adaptation to noise in normal and impaired hearing. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 151, 1741–1753 (2022).

Bell, R., Röer, J. P., Dentale, S. & Buchner, A. Habituation of the irrelevant sound effect: evidence for an attentional theory of short-term memory disruption. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn Mem. Cogn. 38, 1542–1557 (2012).

Wilsch, A., Henry, M. J., Herrmann, B., Maess, B. & Obleser, J. Alpha oscillatory dynamics index temporal expectation benefits in working memory. Cereb. Cortex 25, 1938–1946 (2015).

Hauswald, A., Keitel, A., Chen, Y. P., Rösch, S. & Weisz, N. Degradation levels of continuous speech affect neural speech tracking and alpha power differently. Eur. J. Neurosci. 55, 3288 (2022).

Ala, T. S. et al. Alpha oscillations during effortful continuous speech: from scalp EEG to Ear-EEG. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 70, 1264–1273 (2023).

Villard, S. et al. Energetic and informational masking place dissociable demands on listening effort: evidence from simultaneous electroencephalography and pupillometry. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 154, 1152–1167 (2023).

Clayton, M. S., Yeung, N. & Cohen Kadosh, R. The many characters of visual alpha oscillations. Eur. J. Neurosci. 48, 2498–2508 (2018).

Palva, S. & Palva, J. M. New vistas for α-frequency band oscillations. Trends Neurosci. 30, 150–158 (2007).

Ward, L. M. Synchronous neural oscillations and cognitive processes. Trends Cogn. Sci. 7, 553–559 (2003).

Bailenson, J. N. Nonverbal overload: a theoretical argument for the causes of zoom fatigue. Technol. Mind Behav. 2, tmb0000030 (2021).

Stan, M. M., Topală, I. R., Necşoi, D. V. & Cazan, A. M. Predictors of learning engagement in the context of online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Psychol. 13, 867122 (2022).

Poulsen, A. T., Kamronn, S., Dmochowski, J., Parra, L. C. & Hansen, L. K. EEG in the classroom: synchronised neural recordings during video presentation. Sci. Rep. 7, 43916 (2017).

Neguț, A., Jurma, A. M. & David, D. Virtual-reality-based attention assessment of ADHD: ClinicaVR: classroom-CPT versus a traditional continuous performance test. Child Neuropsychol. 23, 692–712 (2017).

Wang, P., Zhang, X., Ai, X. & Wang, S. Modulation of EEG signals by visual and auditory distractors in virtual reality-based continuous performance tests. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 32, 2049–2059 (2024).

Adams, R., Finn, P., Moes, E., Flannery, K. & Rizzo, A. Distractibility in attention/deficit/ hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): the virtual reality classroom. Child Neuropsychol. 15, 120–135 (2009).

Levy, O. et al. Selective attention and sensitivity to auditory disturbances in a virtually real classroom. Elife 13, RP103235 (2025).

Davidesco, I. Brain-to-brain synchrony in the stem classroom. CBE Life Sci. Educ. 19, es8 (2020).

Xu, K., Torgrimson, S. J., Torres, R., Lenartowicz, A. & Grammer, J. K. EEG data quality in real-world settings: examining neural correlates of attention in school-aged children. Mind Brain Educ. 16, 221–227 (2022).

Mesik, J. & Wojtczak, M. The effects of data quantity on performance of temporal response function analyses of natural speech processing. Front. Neurosci. 16, 963629 (2023).

Song, H., Finn, E. S. & Rosenberg, M. D. Neural signatures of attentional engagement during narratives and its consequences for event memory. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2021905118 (2021).

Mathôt, S., Schreij, D. & Theeuwes, J. OpenSesame: an open-source, graphical experiment builder for the social sciences. Behav. Res Methods 44, 314–324 (2012).

Benedek, M. & Kaernbach, C. A continuous measure of phasic electrodermal activity. J. Neurosci. Methods 190, 80–91 (2010).

Oostenveld, R., Fries, P., Maris, E. & Schoffelen, J. M. FieldTrip: open source software for advanced analysis of MEG, EEG, and invasive electrophysiological data. Comput Intell. Neurosci. 2011, 156869 (2011).