Abstract

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a clinically aggressive hematologic malignancy driven by complex genetic and epigenetic aberrations. Circular RNAs (circRNAs), characterized by covalently closed structures and exceptional stability, have emerged as promising diagnostic biomarkers. However, existing circRNA-based predictive models largely depend on differential expression, overlooking the potential impact of higher-order chromatin organization on circRNA formation and function. Here, we propose a machine learning framework that integrates three-dimensional (3D) genome architecture to refine circRNA selection for AML prediction. By mapping 9,565 circRNAs onto a 3D chromatin model reconstructed from Hi-C data, we analyzed their spatial clustering and biological pathway enrichment. Eighteen pathways exhibited significant 3D aggregation of circRNAs, enabling radial stratification based on nuclear localization. Five circRNA panels were designed using complementary strategies combining expression, pathway, and spatial features. Cross-validation and external validation across six machine learning algorithms showed that the panel derived from the fifth radial layer (Panel-3DG-Radius5) achieved the most robust and consistent performance (ROC-AUC > 0.99). Integrating 3D genomic context reduced feature collinearity while enhancing biological interpretability. Overall, our study establishes a 3D genome-informed paradigm for circRNA biomarker discovery, demonstrating that spatial genome organization can substantially improve the precision and robustness of AML predictive modeling.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) is a genetically heterogeneous hematological malignancy characterized by the clonal proliferation of immature myeloid progenitors, leading to ineffective hematopoiesis, bone marrow failure, and systemic complications, such as anemia, infection, and bleeding1. The disease typically arises from the accumulation of multiple genetic and epigenetic alterations that disrupt the normal differentiation and proliferation of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. These mutations can involve transcription factors, epigenetic regulators, splicing factors, and components of signaling pathways, contributing to the profound heterogeneity observed in AML cases1. Despite advancements in AML classification, diagnostic techniques, and therapeutic approaches—including targeted therapies and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation—the disease remains highly aggressive, with a five-year overall survival (OS) rate of only 28.7%, particularly among elderly patients and those with high-risk cytogenetic profiles2.

Prognostic stratification of AML is primarily based on cytogenetic and molecular markers, as outlined in the European Leukemia Network (ELN) guidelines, which classify patients into favorable, intermediate, and adverse risk groups depending on specific chromosomal abnormalities and gene mutations, such as FLT3, NPM1, and CEBPA3. However, a significant portion of AML patients, especially those lacking recurrent cytogenetic abnormalities, falls into the intermediate-risk category4. Within this group, clinical outcomes can vary widely, and traditional molecular and cytogenetic analyses often fail to provide sufficient resolution for accurate prognostication or treatment decisions. Furthermore, emerging resistance to standard chemotherapy and the high relapse rate in intermediate- and high-risk AML patients further complicate disease management, underlining the urgency to identify novel prognostic and predictive biomarkers. This highlights the need for innovative diagnostic biomarkers and machine learning (ML) approaches that can capture the complexity of AML biology and enable personalized AML risk prediction which may further benefit therapeutic strategies5.

Circular RNAs (circRNAs) are a class of covalently closed, single-stranded RNAs that have garnered significant attention in recent years due to their versatile regulatory functions in gene expression and their emerging roles in various human diseases, including cancer6. Unlike linear RNAs, circRNAs form continuous loop structures lacking 5’ caps and 3’ polyadenylated tails, which renders them highly resistant to exonuclease-mediated degradation7. This structural stability enables circRNAs to accumulate in cells and body fluids, such as blood and plasma, making them ideal candidates for liquid biopsy-based biomarkers. Their abundance, stability, and cell-type-specific expression patterns further enhance their appeal for diagnostic applications, particularly in diseases where early detection is critical, such as AML7.

In the context of hematological malignancies, including AML, circRNAs have been increasingly implicated in leukemogenesis, chemoresistance, and disease progression8. More importantly, numerous studies have demonstrated that circRNAs exhibit distinct expression profiles between AML patients and healthy controls, providing a promising avenue for diagnostic biomarker discovery9. Some circRNAs have been shown to distinguish AML from other leukemias or benign hematologic conditions with high sensitivity and specificity, as reflected in several receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analyses9. Notably, circRNAs can be detected in peripheral blood mononuclear cells and bone marrow aspirates, and their expression can reflect the molecular and cellular landscape of the leukemia microenvironment. This opens new opportunities for developing non-invasive or minimally invasive diagnostic assays that are both cost-effective and reliable.

Emerging evidence suggests that specific circRNAs, such as hsa_circ_0004277, circ_0012152, and circ_POLA2, play critical roles in AML initiation and maintenance by functioning as competing endogenous RNAs (ceRNAs), sponging microRNAs (miRNAs) and thereby modulating the expression of oncogenic or tumor-suppressive mRNA targets10. These functional characteristics not only contribute to AML biology but also reinforce their diagnostic relevance, as alterations in circRNA levels may mirror underlying molecular dysregulation. For instance, circ_0009910 has been reported to promote AML cell proliferation by sponging miR-20a-5p and altering downstream targets involved in cell cycle regulation11,12. Likewise, circ_0104700 has been shown to facilitate leukemogenesis through the JAK/STAT signaling pathway, affecting key regulators of cellular proliferation and differentiation in AML13.

Given these insights, circRNAs represent a novel and underutilized class of biomarkers with strong diagnostic potential. Their expression profiles not only differentiate AML from healthy states but may also distinguish molecular subtypes of AML14, providing an additional layer of granularity in disease classification. Furthermore, the detection of circRNAs through quantitative PCR15 or high-throughput sequencing16 is technically feasible in clinical laboratories, and the incorporation of circRNA signatures into diagnostic workflows could substantially improve the early and accurate detection of AML. These findings collectively highlight the unique advantages of circRNAs as non-invasive, specific, and stable diagnostic biomarkers that could complement or even outperform current molecular assays in the AML diagnostic landscape.

The three-dimensional (3D) genome organization plays a crucial role in gene regulation, chromatin accessibility, and RNA processing, including circRNA biogenesis17 and expression18. Chromatin interactions within topologically associating domains (TADs) influence the circularization of pre-mRNA transcripts, which in turn modulates circRNA expression levels in different cell types, including leukemic cells19,20. Recent advances in high-throughput chromatin conformation capture techniques, such as Hi-C and ChIA-PET, have provided insights into the spatial organization of AML-associated loci and their impact on transcriptional regulation21. Studies have demonstrated that AML-associated circRNAs frequently originate from genomic regions enriched in active chromatin modifications, such as H3K27ac and H3K4me3, suggesting a potential epigenetic regulation of circRNA biogenesis in AML22.

Furthermore, oncogenic translocations, a hallmark of AML pathogenesis, may disrupt chromatin architecture and alter circRNA expression patterns23. For instance, circ-MYBL2, derived from the MYBL2 locus, has been shown to be significantly upregulated in AML patients with FLT3-ITD mutations, contributing to leukemic cell proliferation and survival by enhancing FLT3 kinase translation24. Such findings underscore the importance of integrating 3D genomic information into circRNA-based biomarker discovery and AML prediction models.

ML techniques have revolutionized biomedical research by enabling the identification of complex patterns in high-dimensional datasets25,26. In oncology, ML has been widely applied to transcriptomics, genomics, and epigenomics for cancer classification, patient stratification, and drug response prediction27,28. The application of ML in AML research has gained momentum, particularly in integrating multi-omics data to refine risk classification and improve predictive modeling29,30. By leveraging large-scale genomic datasets, ML algorithms can identify novel biomarkers, including circRNAs, that contribute to AML pathogenesis and prognosis31.

Recent studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of ML-based models in predicting AML outcomes using transcriptomic signatures32. However, most existing models rely on bulk RNA sequencing data, which may overlook critical regulatory elements, such as chromatin interactions and spatial genome organization33. Given the growing evidence supporting the role of 3D genome features in circRNA regulation, integrating these elements into ML-driven circRNA selection may significantly enhance disease predictive models18,34. By incorporating chromatin accessibility, histone modifications, and TAD boundaries into feature selection, ML algorithms may improve the identification of circRNAs with high diagnostic and prognostic value.

Given the increasing recognition of circular RNAs (circRNAs) as functionally relevant and diagnostically valuable biomarkers in AML, and the emerging evidence that their expression is closely regulated by the spatial architecture of the genome, this study aims to develop a novel machine learning (ML)-based framework for AML prediction that leverages both circRNA transcriptomic and 3D genomic information. Traditional circRNA-based biomarker selection methods primarily rely on differential expression, yet they often neglect the regulatory genomic context that governs circRNA biogenesis and distribution. This spatial genome information offers a unique and biologically meaningful perspective for refining biomarker selection. On the other hand, the clinical omics data usually suffer sample size issue, leading to undiscovered collinearity/redundancy between selected biomarkers due to small sample size. The 3D genome information can contribute to diversifying biomarkers by selecting them from spatially different regions under our previous discovery that co-expression, co-pathway, and co-localization are inherently connected18,34,35,36.

In this study, we aim to investigate the spatial organization of circRNAs within the 3D genome and their functional associations with biological pathways. By selecting circRNAs based on their enrichment in distinct pathways and their positional distribution within the 3D chromatin landscape, we hypothesize that this integrative strategy will yield a more diverse and biologically informative circRNA panel. Such a panel is expected to enhance the performance and generalizability of ML models for AML prediction, while also offering mechanistic insights into the spatial regulation of circRNAs in leukemogenesis.

Importantly, incorporating 3D genome architecture into circRNA-based biomarker discovery presents a novel and promising direction for advancing precision diagnostics and deepening our understanding of AML pathophysiology. The diversity introduced by 3D-informed circRNA selection mitigates the risk of overfitting—a common limitation in conventional ML approaches—thereby improving robustness and predictive accuracy on unseen data. Furthermore, this approach enhances the interpretability of the resulting models by grounding feature selection in the biological mechanisms underlying circRNA-mediated regulation during AML initiation and progression.

Results

Differential expression and pathway enrichment

The expression profiles of the two merged datasets are visualized as a circRNA-by-sample heatmap, as shown in Fig. 1A. To further characterize the candidate circRNAs, we computed Spearman correlation coefficients between the expression levels of 9587 circRNAs and AML disease status across samples. The majority of circRNAs exhibited modest correlations, with coefficients falling within the range of ±0.3. However, a subset of circRNAs showed stronger associations, with several displaying coefficients less than –0.6, and notably, five circRNAs demonstrated absolute correlation values exceeding 0.8, indicating a potentially strong relationship with disease state (Fig. 1B).

A circRNA-by-sample expression profiles. AML samples are labeled in yellow, while healthy controls are labeled in blue in the top annotation row. B The Spearman correlation coefficient distribution of 9587 circRNAs and AML disease status across samples. C The volcano plot for identification of differentially expressed circRNAs. D The most significantly enriched pathways from Gene Ontology enrichment analysis.

Differential expression analysis revealed a total of 806 circRNAs that were significantly dysregulated between AML patients and healthy controls, including 513 upregulated and 293 downregulated circRNAs (Fig. 1C). These differentially expressed circRNAs were subsequently subjected to Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis. After implementing a redundancy filtering procedure to ensure that each circRNA was uniquely assigned to its most significantly enriched pathway, a final set of 34 enriched biological pathways was retained, collectively involving 386 circRNAs (Fig. 1D).

Spatial clustering of circRNA on enriched pathway

To assess the spatial organization of pathway-associated circRNAs within the nuclear architecture, we performed K-means clustering on their 3D genomic coordinates. Silhouette coefficients were calculated for each pathway and compared against two background references: (1) all genomic bin coordinates and (2) the full set of differentially expressed circRNAs. Based on this analysis, 18 pathways exhibited significantly enhanced spatial clustering relative to both backgrounds, suggesting that circRNAs within these pathways may be co-localized in 3D space and potentially co-regulated (Fig. 2A). Fig. 2B–D show the circRNA spatial distribution belonging to the enriched 18 pathways of cellular component (CC), biological process (BP), and molecular function (MF) respectively.

A The 18 biological pathways demonstrated significantly enhanced spatial clustering of circRNAs relative to both background references (genomic bin coordinates and all differentially expressed circRNAs), indicating potential 3D co-localization and coordinated regulation. B–D Three-dimensional spatial distributions of circRNAs associated with the enriched pathways categorized under cellular component (CC), biological process (BP), and molecular function (MF), respectively.

Radial positional effects on circRNA selection (pre-experiment)

After mapping all the 9565 circRNAs to the 3D genome space, we partitioned the whole genome into 18 zooms with different radius to the nuclear center (Fig. 3A, B), i.e., radius_bin. The detailed number of circRNAs within each zoom is shown in Fig. 3C. To determine which radius zoom contains circRNA with more AML discriminatory power and how many circRNA should be selected from these radius zooms, we conducted the abovementioned pre-experiment. Fig. 3D illustrate the results of circRNA-based AML prediction under different combinations of radius_bin and circRNA panel size n, based on cross-validation. Specifically, Fig. 3D presents the outcomes of 100 rounds of 10-fold cross-validation on the GSE158596 dataset, where in each round, n circRNAs were randomly selected from a given radius_bin. Supplementary Fig. 1 shows the corresponding results from 1000 rounds of random selection followed by model validation on the merged dataset (94 samples for training and 26 for testing). To exam the prediction contributions of circRNAs from different radius, we calculated the SHAP score distribution of different circRNAs, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 2. The circRNAs selected using 3D genome information exhibit higher contribution comparing to circRNAs from Panel-TopN and Panel-Pathway.

A Schematic representation of the 3D nuclear space centered at [0, 0, 0], where all 9565 circRNAs were mapped based on their inferred genomic positions. B The nuclear space was divided into 18 concentric radial intervals (radius_bins) extending outward from the nuclear center to the maximum circRNA distance (R_max). C Bar plot showing the number of circRNAs assigned to each of the 18 radial bins. D The average AUC values obtained from 100 rounds of 10-fold cross-validation on the GSE158596 dataset, evaluating circRNA panels of different sizes (n = 3, 5, 10, 20, 50) randomly selected from each radius_bin.

Analysis of the mean AUC values across repeated samplings reveals several consistent patterns: 1) The average AUC exhibits systematic fluctuations across different radius_bin and n combinations, a trend observed across multiple ML models. 2) Panels with n = 50 consistently yielded higher mean AUC values compared to smaller panel sizes, likely due to the increased diversity and richness of expression information captured by larger sets of circRNAs. 3) Notably, radius_bin = 1 and radius_bin = 5 displayed pronounced peaks in AUC performance, with the peak at radius_bin = 5 being particularly evident for n = 50.

To investigate the underlying factors contributing to the differential predictive performance across radial zones, we conducted GO enrichment analysis for circRNAs in each radius_bin interval. Using a significance threshold of adjusted p-value < 0.05 and q-value < 0.05, we found that all radius_bin groups except for radius_bin = 5 showed substantial pathway enrichment. In contrast, the 103 genes associated with circRNAs in radius_bin = 5 did not map to any enriched GO terms under the same cutoff criteria. Even when the significance threshold was relaxed to p-value and q-value < 0.1, only a small number of genes from this group were mapped to a limited set of pathways (Supplementary Data 1). These results suggest that circRNAs located within radius_bin = 5 exhibit greater biological functional diversity, potentially contributing to their enhanced ability to capture heterogeneous AML-related expression patterns and improve model performance.

Panel selection and prediction results

Among the 18 pathways identified as exhibiting significant spatial clustering relative to background distributions based on 3D genome (3DG) information, a total of 51 cluster centroids were determined. For fairness in comparing different panels, we standardized the number of circRNAs in each panel to 51 across subsequent analyses. An exception was made for Panel-3DG-Radius1, where the number of available circRNAs within the corresponding radial interval was limited, resulting in a slightly smaller panel size (Table 1). Fig. 4 demonstrates the spatial distribution of the panels.

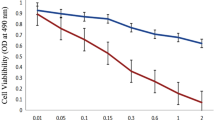

The results of 100 rounds of 10-fold cross-validation using six distinct ML models on the GSE158596 dataset for the five circRNA panels are summarized in Table 2 (detailed in Supplementary Data 2). The train-validation performance (ROC & PR curves) is demonstrated in Fig. 5. For four of the panels—excluding Panel-3DG-Radius1—the area under the ROC curve (AUC) values are consistently close to 1.0, indicating exceptionally high predictive performance on the current dataset, albeit with a potential risk of overfitting. In comparison, Panel-3DG-Radius1 demonstrated relatively lower performance, suggesting its predictive capacity is slightly inferior to that of the other panels under the same evaluation conditions.

To further evaluate the performance of models constructed from different circRNA panels—particularly their generalizability—we conducted a validation analysis on the merged dataset comprising 120 samples. For each model, we computed both the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC-AUC) and the area under the precision–recall curve (PR-AUC), as summarized in Table 3 (detailed in Supplementary Data 2). The ROC curves and precision–recall curves for all models are demonstrated in Supplementary Fig. 3. The results demonstrate that Panel-3DG-Radius5, which incorporates 3D genome spatial information, consistently achieved the best performance across nearly all ML models. Specifically, the average F1 Score and Kappa Score are 0.907 and 0.678, across the seven ML models, using Panel-TopN, while using Panel-Radis5, the two averaged scores are increased to 0.936 and 0.761, respectively. These findings highlight its superior generalizability and robustness in distinguishing AML from healthy controls under diverse predictive frameworks.

Analysis of different circRNA panels

To enable a more comprehensive comparison of panel performance, we conducted in-depth analyses on the top four panels that demonstrated superior predictive accuracy. We examined the degree of feature redundancy by comparing the pairwise correlation coefficients among circRNAs within the Panel-TopN, Panel-Pathway, and Panel-3DG-Cluster (Fig. 6C, Table 4). The results reveal that a stepwise selection process—beginning with differentially expressed circRNAs, followed by pathway enrichment, 3D genome spatial clustering, and final circRNA selection from functionally coherent pathways—progressively mitigates the issue of multicollinearity among features. Specifically, the mean absolute value of the pairwise correlation coefficients followed the order: Panel-TopN > Panel-Pathway > Panel-3DG-Cluster. Notably, Panel-3DG-Radius5 exhibited the lowest overall feature correlations, consistent with earlier findings that circRNAs within radius_bin = 5 were not significantly enriched in any specific GO pathway. This observation supports the conclusion that circRNAs selected from this region represent a highly diverse feature set in terms of biological function and spatial organization.

An intriguing question arises: why did Panel-3DG-Cluster, despite its relatively low feature collinearity, not achieve the same level of generalizability as Panel-3DG-Radius5? To address this, we compared the absolute values of Spearman correlation coefficients between each circRNA and disease status across the four panels (Fig. 6A). CircRNAs in Panel-3DG-Radius5 tended to exhibit relatively lower correlations with AML status, which may partially explain its slightly lower predictive performance in some metrics. In contrast, Panel-TopN included circRNAs with the highest correlations to disease labels, yet suffered from substantial feature redundancy.

Panel-3DG-Radius5 appears to strike a favorable balance between predictive power and feature diversity. Although its constituent circRNAs individually display weaker correlations with disease status, their spatially informed and non-redundant nature may help avoid multicollinearity and overfitting—two common challenges in ML—thereby contributing to its superior generalization performance.

Further supporting this, a Venn diagram of the four panels (Fig. 6B) shows that 45 circRNAs in Panel-3DG-Radius5 are entirely absent from the other three panels. This indicates that selecting circRNAs based on their radial distance from the nuclear center captures unique, complementary information beyond differential expression and pathway enrichment. These results underscore the added value of incorporating 3D genome spatial context into circRNA panel design for disease prediction Fig. 7.

A circRNA RNA-Seq Data Analysis: a pipeline from downloading raw data from the GEO database, alignment, circRNA quantification, to the final integration into a circRNA expression matrix. B Hi-C data analysis: This involves differential expression analysis, GO enrichment analysis, mapping circRNAs to their coordinates in the 3D genome, clustering based on 3D genomic coordinates, and stratifying circRNAs by radius R. C Pre-Experiment: a preliminary analysis was conducted to assess the impact of circRNA expression levels across different R-based strata on disease prediction. D Panel Selection: based on the analytical results, five circRNA panels were selected. E Evaluation: The five panels were evaluated using various machine learning models, with all models assessed via 10-fold cross-validation and external validation.

Lastly, the absence of any overlap between Panel-3DG-Radius5 and Panel-3DG-Cluster—despite both panels integrating different aspects of 3D genome information (radial distance vs. spatial clustering)—suggests that multiple orthogonal features derived from 3D chromatin architecture can be leveraged to guide circRNA selection. This highlights the potential of multi-dimensional 3D genome-informed strategies to enhance both the robustness and interpretability of circRNA-based predictive models.

Discussion

In this study, we present a novel framework for AML prediction by integrating circular RNA (circRNA) transcriptomic profiles with spatial features derived from 3D genome architecture. Our results demonstrate that incorporating 3D genomic context into biomarker selection significantly enhances the generalizability, interpretability, and robustness of ML models used for AML classification. Previous studies have established circRNAs as stable and functionally relevant RNA molecules with diagnostic and prognostic potential across various cancer types, including AML. However, most circRNA-based classifiers rely solely on differential expression, which, while effective in detecting disease-associated signatures, may lead to overfitting, especially in high-dimensional low-sample settings common in clinical omics data. Our approach addresses this limitation by incorporating spatial chromatin features, leveraging the insight that circRNA biogenesis and function are modulated not only by sequence and expression but also by the spatial configuration of the genome.

The spatial genome is increasingly recognized as a key regulator of transcriptional programs in both normal and malignant hematopoiesis. TADs, loop domains, and compartmentalized chromatin territories have been shown to influence promoter-enhancer interactions, alternative splicing, and non-coding RNA expression, including that of circRNAs. In this context, we hypothesized that circRNAs located in spatially distinct nuclear regions may exhibit greater functional heterogeneity and provide more diverse information for ML-based disease prediction. To test this hypothesis, we mapped 9,565 circRNAs from two GEO AML datasets into a high-resolution 3D genome model of the IMR90 cell line and stratified them based on their radial distance from the nuclear center. We further clustered differentially expressed circRNAs based on spatial proximity and pathway enrichment. This analysis led to the identification of 18 biological pathways exhibiting significant spatial circRNA clustering, supporting the idea that co-regulated circRNAs may also be co-localized in 3D space. We constructed five circRNA panels using different selection strategies: based on expression rank (Panel-TopN), pathway membership (Panel-Pathway), spatial clustering within enriched pathways (Panel-3DG-Cluster), and radial nuclear positioning (Panels-3DG-Radius1 and -Radius5). Across extensive benchmarking using six ML algorithms, Panel-3DG-Radius5 consistently achieved the highest ROC-AUC and PR-AUC values in both cross-validation and independent validation settings. This panel also showed the greatest generalizability, outperforming models constructed from more traditional selection approaches. With more circRNA dataset available for AML in the future, the translational power and robustness can be validated.

The high AML prediction accuracy of Panel-3DG-Radius5 may be attributed to several factors. First, circRNAs in radius_bin = 5 were distributed at an intermediate nuclear distance, a region where chromatin is known to be transcriptionally active yet less compact than at the periphery. These circRNAs were not significantly enriched in specific pathways, suggesting functional heterogeneity and low mutual redundancy. This is supported by the observation that the pairwise correlation coefficients among Panel-3DG-Radius5 circRNAs were the lowest among all panels. Such low multicollinearity is advantageous for ML models, as it reduces overfitting and improves the robustness of predictions. In contrast, panels constructed from highly correlated features (e.g., Panel-TopN) achieved high training performance but showed reduced generalization. Interestingly, Panel-3DG-Cluster, which also utilized 3D information via pathway-specific clustering, did not perform as well in external validation despite its low feature collinearity. Further analysis revealed that while this panel included biologically coherent circRNAs, they lacked the spatial and functional diversity observed in Panel-3DG-Radius5. Moreover, Spearman correlation analysis showed that circRNAs in Panel-3DG-Cluster were more strongly associated with AML status, suggesting that they may reflect a more static and possibly over-optimized selection for the training dataset. This reinforces the need to balance predictive power with feature diversity in high-dimensional biomarker discovery.

Another key strength of our approach lies in its biological interpretability. By integrating pathway enrichment and chromatin spatial features into panel selection, we anchor model construction in mechanistic insights rather than treating circRNA expression as a black-box feature set. This is particularly important in clinical contexts, where understanding why a biomarker works is critical for translational acceptance. For instance, the absence of overlapping circRNAs between Panels-3DG-Radius5 and -3DG-Cluster, despite both incorporating 3D information, highlights the multifaceted nature of spatial genome regulation and opens avenues for orthogonal feature integration.

While our findings are promising, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the 3D genome model used in this study is not hematopoietic in origin. Although general chromatin folding principles are preserved across cell types, cell type-specific 3D features may further improve circRNA localization accuracy. Future efforts should focus on constructing leukemia-specific 3D genome maps, particularly from AML stem and progenitor cells, to refine spatial annotation. Second, although we used the largest publicly available RNA-seq AML circRNA datasets to date, the sample size remains modest. Especially, the external validation dataset (GSE149237) is relatively small, and the use of replicate-split samples as independent observations may lead to optimistic estimates of generalizability. Consequently, the external validation results should be interpreted cautiously. Future validation using larger, independent patient cohorts will be essential to further confirm the robustness of our findings. Moreover, larger, multi-cohort studies are necessary to validate the reproducibility of our findings across clinical subtypes, treatment stages, and ethnic populations. The use of paired samples pre- and post-treatment could help establish whether 3D-informed circRNA signatures have prognostic or treatment-monitoring utility. Third, our current framework evaluates circRNA panels in binary classification (AML vs. healthy). Extending this approach to multiclass problems—e.g., stratifying AML by cytogenetic risk, molecular subtype, or treatment response—will be essential for clinical deployment. Additionally, future work could incorporate multi-omics integration (e.g., chromatin accessibility, methylation, proteomics) to further enhance biomarker robustness and model interpretability. Finally, from a technical perspective, future improvements in spatial feature engineering (e.g., incorporating compartmental domains, local density, chromatin marks) could offer deeper insights into why specific circRNAs are predictive and how they interact with the 3D genome. Moreover, while our study enhances interpretability by grounding circRNA selection in spatial genome context, we did not apply model explanation tools, such as SHAP values or permutation importance. Incorporating these methods in future work would allow us to quantify the contribution of individual circRNAs to predictions, thereby complementing spatially informed feature selection with deeper mechanistic interpretability.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that integrating 3D genomic information into circRNA selection provides a biologically grounded and technically robust strategy for AML prediction. The Panel-3DG-Radius5 exemplifies how spatial genome context can diversify circRNA selection, reduce redundancy, and enhance model performance. More broadly, our work establishes a conceptual framework for leveraging 3D nuclear architecture to guide non-coding RNA-based diagnostics, with potential applications across hematologic and solid malignancies. As chromatin structure and spatial transcriptomics technologies mature, such integrative approaches are poised to play a central role in precision oncology.

Methods

circRNA datasets

After exploring all the circRNA datasets of AML in GEO, the two datasets, GSE15859637 and GSE14923738, were adopted in this study were obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, given their adequate sample size comparing to other datasets. The GSE158596 dataset contains 94 samples in total, including 78 positive samples derived from AML leukemic blasts and 16 negative samples derived from healthy G-CSF-mobilized CD34+ hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs). Among these, 90 samples have two biological replicates each. GSE149237 contains 13 samples, including eight positive and five negative samples, with each sample having two biological replicates. Together, the two datasets comprise a total of 210 (184 positive + 26 negative) samples of paired-end high-throughput sequencing data.

RNA-seq data analysis

After obtaining the raw sequencing data from GEO database, we devised a pipeline to generate the circRNA-by-sample expression matrix, to profile the circRNA expression levels across different samples. Based on the Run accession numbers listed in the SRA Run Selector for each dataset, we used the fastq-dump tool from the SRA Toolkit version 3.0.7 to download the high-throughput sequencing data, resulting in 210 pairs of FASTQ sequence files. The BWA-MEM algorithm was used to align the sequencing reads to the reference genome, resulting in alignment files in SAM format. The reference genome FASTA file (hg19.fa) used for alignment was downloaded from the UCSC database. Next, the CIRI2 software39,40 was applied to quantify and annotate circRNAs for each sample based on the alignment results and the gene annotation file (hg19.gtf) also obtained from the UCSC database. This step produced output files listing circRNA IDs and their corresponding expression levels for each sample.

Before constructing the integrated expression matrix, we first process the samples that have replicates. For the 90 samples with replicates in the GSE158596 dataset, correlation analysis was performed between the two replicate quantification result files for each sample. The results showed that the replicates of most samples had a correlation greater than 85% (only two samples were slightly lower, but both had correlation coefficients above 80%) (Supplementary Data 3). Therefore, for these samples with replicates, we merged the two circRNA quantification files by taking the average expression value of each circRNA across the two files as the final expression value for that sample. Similarly, for the GSE149237 dataset, we calculated the correlation coefficients between the two replicates of each of the 13 samples. Since the correlation between replicates in this dataset was generally low (Supplementary Data 4), the 26 resulting quantification files were treated as 26 independent samples (16 positive and ten negative).

After these processing steps, each dataset yielded their respective expression matrix. In these matrices, row names represent circRNA IDs, column names represent sample IDs, and each cell contains the expression level of a given circRNA in a given sample. The finalized expression matrix for the GSE158596 dataset contains a total of 9,587 circRNAs. This matrix was selected for subsequent analysis, including panel selection and cross-validation. To remove batch effect, we performed z-score normalization on each dataset separately, leading to zero-mean one-std distribution of each dataset. The PCA plots before and after z-score normalization is shown in Supplementary Fig. 4. The expression matrices were then merged. From the resulting integrated dataset of 120 samples, 94 samples (74 positive and 20 negative) were randomly selected as the training set, and the remaining 26 samples (20 positive and six negative) were treated as validation set.

Hi-C data analysis and circRNA 3D genome coordinates acquisition

We collected and processed Hi-C data according to the pipeline we developed41,42, to obtain a whole-genome chromatin contact heatmap where the length of each chromatin unit equal to 500k base pairs. Based on the contact heatmap, we computationally built chromatin 3D structure models using molecular dynamics42, so that each chromatin unit with size 500 kb has a <x, y, z> spatial coordinate. The circRNA quantification output included both circRNA identifiers and associated annotation data. Each circRNA ID was formatted as “chromosome:Start|End”, and annotation fields contained the corresponding UCSC-format Gene ID. To enable downstream functional analyses, gene identifiers were converted to official gene symbols using the UCSC Gene ID Conversion Tool (https://biotools.fr/human/ucsc_id_converter; Supplementary Data 5).

Genomic coordinates encoded for each circRNA were used to retrieve their spatial localization within the 3D genome conformation. CircRNAs were first assigned to linear genomic loci based on their chromosomal origin and genomic span. These loci were then mapped to their corresponding spatial coordinates using a reference file that defines a one-to-one mapping between circRNA IDs and their 3D coordinates in nuclear space. Through this approach, 9,565 circRNAs were successfully mapped to the 3D genome spatial space. Note that a small subset of circRNAs, including 21 located on chromosome Y and one on an unplaced contig (chrUn), could not be mapped due to absence of defined spatial coordinates in the selected 3D genomic reference.

Differentially expressed circRNAs and pathway enrichment

Differential expression analysis was performed on the expression matrix derived from the GSE158596 dataset using the R package DESeq2 to identify circRNAs differentially expressed between healthy and AML patient samples (Supplementary Data 6). The analysis was conducted using a log2 fold change cutoff of 0.15 and a p-value threshold of 0.05. Such setting is to ensure that circRNAs with modest yet potentially biologically meaningful changes were not excluded. Note that circRNAs often exhibit smaller expression shifts in AML, and this threshold allowed us to retain a broader, more sensitive candidate pool while still maintaining statistical rigor.

Subsequently, all differentially expressed circRNAs were subjected to GO enrichment analysis, with the parameters p-value cutoff = 0.05 (adjusted p-value) and q-value cutoff = 0.05 (Supplementary Data 7). Given that some circRNAs were enriched across multiple pathways, a redundancy removal step was implemented to ensure each circRNA was uniquely assigned to a single GO term. Specifically, for any circRNA enriched in multiple pathways (e.g., both pathway A and pathway B), the circRNA was retained only in the pathway with the smaller p-value, thereby ensuring that each circRNA corresponded to a single, most significant enriched term (Supplementary Data 8).

Cluster analysis on 3D genome and nucleic radius stratification

The K-means clustering was independently performed on the circRNAs within each enriched pathway using their spatial coordinates in the 3D genome. The set of all genomic bin coordinates and the coordinates of all differentially expressed circRNAs served as the background reference. For each pathway, the optimal number of clusters (K) was determined by selecting the value that yielded the highest silhouette coefficient. Silhouette scores were then calculated for each pathway and corresponding background sets. A pathway was retained for further analysis if it met the following criteria: I) The pathway’s silhouette coefficient exceeded a defined threshold (silhouette_cutoff = 0.5); II) The silhouette coefficients for all genomic bin backgrounds were below silhouette_cutoff − 2 × margin (margin = 0.02); III) The silhouette coefficients for the background consisting of all differentially expressed circRNAs were below silhouette_cutoff − margin.

Pathways that satisfied all three conditions were considered to exhibit significantly stronger spatial clustering than expected by background distribution and were thus prioritized (Supplementary Data 9). Additionally, the Euclidean distance from the nuclear center at coordinate [0, 0, 0] was computed for each of the 9,565 circRNAs. The maximum observed distance was denoted as R_max, representing the furthest spatial extent from the nuclear center among all circRNAs. The range from the center to R_max was evenly divided into 20 concentric radial intervals. Due to the relatively small number of circRNAs within the innermost three intervals, these were merged into a single group, resulting in 18 final radius-based spatial intervals. The start and end distances of each interval, along with the number of circRNAs within them, are provided in Supplementary Data 10.

Radius positioning of circRNA in AML prediction (pre-experiment)

For each combination of radius interval (radius_bin = 0 ~ 17) and circRNA count (n = 3, 5, 10, 20, 50), we randomly selected n circRNAs from a given radius_bin to form a panel, and evaluated its predictive performance using two strategies: (a) On the GSE158596 dataset with 94 samples, we randomly selected 100 times in each (radius_bin, n) combination and performed 100 rounds of 10-fold cross-validation for each random selection. (b) On the merged dataset of 120 samples, we randomly selected 1000 times in each (radius_bin, n) combination and used 94 samples as the training set and 26 samples as the test set to perform disease prediction.

For both (a) and (b), the average AUC (Area Under the Curve) across all repetitions was calculated and compared across combinations in order to identify the optimal (radius_bin, n) parameter setting.In both validation strategies, six different ML models were used for cross-validation and prediction as described hereinbelow.

circRNA panel selection and prediction model evaluation

The overall workflow for circRNA panel selection and model fitting is illustrated in Fig. 1. Spearman correlation coefficients were calculated in R using the DescTools package. Model construction was carried out using Python’s scikit-learn library (with XGBoost implemented via an additional external package). All models were evaluated using 100 rounds of 10-fold cross-validation on the GSE158596 dataset, as well as validation on the merged dataset. Additionally, a multilayer perceptron (MLP) model was included specifically in the validation stage for the evaluation of model generalization. Fig. 1 demonstrates the workflow of this study. Detailed ML parameter settings are listed in Supplementary Data11.

Data Availability

The original dataset can be downloaded from GEO database under the accession numbers GSE158596 and GSE149237. The data are provided in Supplementary Data, any additional data is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The source code is available here: https://github.com/feelingyi1840/circRNA_AML.

References

Y. Mirazimi, A. H. Aghayan, A. Atashi, D. Mohammadi, M. Rafiee, Prognostic value of circular RNAs expression and their correlation with clinicopathological features in acute myeloid leukemia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Hematol. 104, 2095–2124 (2025).

Gao, L. et al. Circular RNA as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers in hematological malignancies:systematic review. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 23, 15330338241285149 (2024).

Ye, F. et al. Screening and validating circular RNAs that estimate disease risk and treatment response of pediatric acute myeloid leukemia: a microarray-based analyses and RT-qPCR validation. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 149, 11233–11245 (2023).

Rahmati, A. et al. Circular RNAs: pivotal role in the leukemogenesis and novel indicators for the diagnosis and prognosis of acute myeloid leukemia. Front. Oncol. 13, 1149187 (2023).

Liu, Y. et al. Role of microRNAs, circRNAs and long noncoding RNAs in acute myeloid leukemia. J. Hematol. Oncol. 12, 51 (2019).

Li, M., Meng, F. & Lu, Q. Expression profile screening and bioinformatics analysis of circRNA, LncRNA, and mRNA in acute myeloid leukemia drug-resistant cells. Turk. J. Haematol. 37, 104–110 (2020).

Pourrajab, F., Zare-Khormizi, M. R., Hashemi, A. S. & Hekmatimoghaddam, S. Genetic characterization and risk stratification of acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Manag. Res. 12, 2231–2253 (2020).

Hu, L., Zheng, B., Yang, Y., Chen, C. & Hu, M. Construction of circRNA-miRNA-mRNA network reveal functional circRNAs and key genes in acute myeloid leukemia. Int J. Gen. Med. 16, 1491–1504 (2023).

Kristensen, L. S., Hansen, T. B., Veno, M. T. & Kjems, J. Circular RNAs in cancer: opportunities and challenges in the field. Oncogene 37, 555–565 (2018).

Zhou, M., Gao, X., Zheng, X. & Luo, J. Functions and clinical significance of circular RNAs in acute myeloid leukemia. Front Pharm. 13, 1010579 (2022).

Ping, L., Jian-Jun, C., Chu-Shu, L., Guang-Hua, L. & Ming, Z. Silencing of circ_0009910 inhibits acute myeloid leukemia cell growth through increasing miR-20a-5p. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 75, 41–47 (2019).

Huang, W. et al. Regulatory mechanism of miR-20a-5p expression in cancer. Cell Death Discov. 8, 262 (2022).

Chen, K., Ning, X., Yan, X. & Song, L. Circ_0104700 contributes to acute myeloid leukemia progression by enhancing MCM2 expression through targeting miR-665. Hematology 28, 2227489 (2023).

Singh, V., Uddin, M. H., Zonder, J. A., Azmi, A. S. & Balasubramanian, S. K. Circular RNAs in acute myeloid leukemia. Mol. Cancer 20, 149 (2021).

Das, A., Das, D. & Panda, A. C. Validation of circular RNAs by PCR. Methods Mol. Biol. 2392, 103–114 (2022).

Li, X. & Wu, Y. Detecting circular RNA from high-throughput sequence data with de Bruijn graph. Bmc Genomics 21, 749 (2020).

Li, A. et al. Increasing upstream chromatin long-range interactions may favor induction of circular RNAs in LysoPC-activated human aortic endothelial cells. Front. Physiol. 10, 433 (2019).

Chi, R. et al. Prediction of Alzheimer’s disease based on 3D genome selected circRNA. J. Prev. Alzheimers Dis. 11, 1055–1062 (2024).

Fang, C., Rao, S., Crispino, J. D. & Ntziachristos, P. Determinants and role of chromatin organization in acute leukemia. Leukemia 34, 2561–2575 (2020).

Kloetgen, A. et al. Three-dimensional chromatin landscapes in T cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat. Genet 52, 388–400 (2020).

Akdemir, K. C. et al. Disruption of chromatin folding domains by somatic genomic rearrangements in human cancer. Nat. Genet. 52, 294–305 (2020).

Chen, J. B. et al. Modeling circRNA expression pattern with integrated sequence and epigenetic features demonstrates the potential involvement of H3K79me2 in circRNA expression. Bioinformatics 37, 3386 (2021).

Conn, V. M. et al. Circular RNAs drive oncogenic chromosomal translocations within the MLL recombinome in leukemia. Cancer Cell 41, 1309–1326 e1310 (2023).

Sun, Y. M. et al. Chen, circMYBL2, a circRNA from MYBL2, regulates FLT3 translation by recruiting PTBP1 to promote FLT3-ITD AML progression. Blood 134, 1533–1546 (2019).

Yuan, Y. et al. DeepGene: an advanced cancer type classifier based on deep learning and somatic point mutations. BMC Bioinforma. 17, 476 (2016).

Trac, Q. T. et al. Prediction model for drug response of acute myeloid leukemia patients. npj Precis. Oncol. 7, 32 (2023).

Cai, Z., Poulos, R. C., Liu, J. & Zhong, Q. Machine learning for multi-omics data integration in cancer. iScience 25, 103798 (2022).

Yuan, Y. et al. Cancer type prediction based on copy number aberration and chromatin 3D structure with convolutional neural networks. BMC Genomics 19, 565 (2018).

Y. Song, et al. Classification of acute myeloid leukemia based on multi-omics and prognosis prediction value. Mol. Oncol. 19, 1836–1854 (2025).

Kosvyra, A., Karadimitris, A., Papaioannou, M. & Chouvarda, I. Machine learning and integrative multi-omics network analysis for survival prediction in acute myeloid leukemia. Comput. Biol. Med. 178, 108735 (2024).

H. Li, Y. Qian, Z. Sun, H. Zhu, Prediction of circRNA-disease associations via graph isomorphism transformer and dual-stream neural predictor. Biomolecules 15, 234 (2025).

Warnat-Herresthal, S. et al. Scalable prediction of acute myeloid leukemia using high-dimensional machine learning and blood transcriptomics. iScience 23, 100780 (2020).

Lieberman-Aiden, E. et al. Comprehensive mapping of long-range interactions reveals folding principles of the human genome. Science 326, 289–293 (2009).

K. Y. Li, et al. 3D genome-selected microRNAs to improve Alzheimer’s disease prediction. Front. Neurol. 14, 1059492 (2023).

Shi, Y. et al. Chromatin accessibility contributes to simultaneous mutations of cancer genes. Sci. Rep. 6, 35270 (2016).

Guo, Z. H. et al. 3D genome assisted protein-protein interaction prediction. Future Gener. Comp. Sy 137, 87–96 (2022).

Lux, S. et al. Deregulated expression of circular RNAs in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood Adv. 5, 1490–1503 (2021).

Davis, A. G. et al. Alternative polyadenylation dysregulation contributes to the differentiation block of acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 139, 424–438 (2022).

Gao, Y., Wang, J. & Zhao, F. CIRI: an efficient and unbiased algorithm for de novo circular RNA identification. Genome Biol. 16, 4 (2015).

Gao, Y., Zhang, J. & Zhao, F. Circular RNA identification based on multiple seed matching. Brief. Bioinform 19, 803–810 (2018).

Shin, H. et al. TopDom: an efficient and deterministic method for identifying topological domains in genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, e70 (2016).

Shi, Y. et al. DeepAntigen: a novel method for neoantigen prioritization via 3D genome and deep sparse learning. Bioinformatics 36, 4894–4901 (2020).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to all the involved participants for their support. This project is supported by the National Key Research and Development Program (2022YFE0125300, 2024YFC2707002), Innovation Program of Shanghai Municipal Education Commission (2023ZKZD16), Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Major Project (2017SHZDZX01, 20JC1418600), the Shanghai Leading Academic Discipline Project (B205), Key Technology Breakthrough Program of Ningbo Sci-Tech Innovation YONGJIANG 2035 (2024Z221), and Shanghai Jiao Tong University STAR Grant (YG2026LC14, YG2025QNA46, YG2023ZD26, YG2022ZD024, YG2022QN111, YG2023LC14, YG2024QNA59).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.S., G.H., H.L., Y.L., H.C., M.T., K.F., and H.K. conceptualized and designed the study; Y.S. and G.H. supervised the study; Z.Y., W.Y., R.W., and S.Y. acquired the data; Z.Y., C.P., X.R., and W.D. organized the data; Y.S. and Z.Y. designed the ML analysis pipeline; Z.Y. conducted the ML in silicon experiments; Z.Y., W.Y., R.W., H.C., H.S., and S.Y. discovered the biological insights. Y.S. and Z.Y. wrote and reviewed the manuscript; Y.S., G.H., H.L., Y.L., Y.Z., and H.S. revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yuan, Z., Yan, W., Wang, R. et al. Machine learning prediction for AML based on 3D genome selected circRNA. npj Syst Biol Appl 12, 16 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41540-025-00638-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41540-025-00638-3