Abstract

Twice per year, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends strains for seasonal influenza vaccines to ensure vaccine strains match circulating viruses. However, new variants can emerge after vaccine strain selection, leading to mismatches between vaccine and circulating viruses. New vaccine platforms could enable later than currently practiced strain selection, which could reduce mismatch frequency. Here, we investigated whether delaying vaccine strain selection by three months could improve vaccine match. We compared haemagglutinin epitope mutations and hemagglutination inhibition (HI) titers of historical and hypothetical vaccine strains selected using a reproducible method against dominant circulating viruses during 63 influenza seasons in the United States, Europe, and Australia and New Zealand between 2002 and 2023. Vaccine match to circulating viruses, based on epitope mutations, could be improved in 51/63 seasons by our reproducible strain selection method while preserving WHO timing. Delaying selection could have further improved the match in 14/63 seasons. Based on a ≥4-fold match improvement in HI titer, our reproducible strain selection with WHO timing could have improved the match in 12/63 seasons and a further 7/63 seasons if selected later. Improvements in vaccine match can be achieved while preserving the current WHO timing, with further improvements possible by delaying strain selection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Seasonal influenza virus infections lead to considerable health and economic burdens every year, causing an estimated 291,000 to 646,000 respiratory deaths and affecting 5–15% of the global population1,2. The most common strategy for protection against seasonal influenza viruses is vaccination. However, due to the evolutionary capacity of seasonal influenza viruses, frequent changes to its antigenic phenotype to escape immune responses raised to prior infections and vaccinations necessitate regular vaccine updates2. Currently available seasonal influenza vaccines target the immunodominant hemagglutinin (HA) surface protein, with most vaccines being produced in chicken eggs3. The manufacturing process of these egg-based vaccines requires 6–8 months4,5 As a result, the World Health Organization (WHO) convenes biannually in February and September to select the influenza vaccine strains for the upcoming seasons in the northern and southern hemispheres, respectively. The WHO selects one strain for each influenza subtype, including A/H3N2, A/H1N1pdm, and B/Victoria. The vaccine strains are selected by expert consensus based on a variety of evidence, including molecular and surveillance data, antigenic hemagglutinin inhibition (HI) assay data, structural protein modeling data, growth characteristics, immunogenicity, and forecasts/predictions of virus circulation and clade frequencies at the start of the next influenza season.

Influenza vaccine effectiveness (VE) varies from season to season, depending on a variety of factors such as the match between the vaccine strain and the circulating strains, population exposure history, antigenic drift, and an assortment of other host- and virus-specific factors6,7,8. In the United States (US), VE estimates fluctuated between 19% and 60% between the 2010–2011 season and the 2022–2023 season, with the exclusion of the COVID-19 pandemic 2020–2021 season9. Estimates for VE in Europe varied from 14.4% to 61% between the 2010–2011 season and the 2022–2023 season, excluding the 2020–2021 season10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20. In Australia, the VE was estimated to fluctuate between 37% and 60% between the 2012 season and the 2019 season21,22,23,24. Overall, VE estimates for A/H3N2 tend to be lower compared to the other subtypes6,10,14,21,23,25. During some seasons with low VE, a mismatch between the vaccine strain and the circulating strain has been reported6,26.

Due to VE variability and occasional mismatches between the vaccine and circulating viruses, the timing of the vaccine strain selection has been a point of discussion with questions focused on whether making later decisions than currently practiced could improve the match of vaccine viruses to circulating viruses27. For egg-based influenza vaccines that require substantial manufacturing lead time, implementing a later-timed vaccine strain selection would be highly challenging. However, new vaccine technologies, such as recombinant and mRNA vaccines, have shorter production timelines than egg-based vaccines, which might allow later selection. Phase I/II and III clinical trials of seasonal influenza mRNA vaccines have shown similar safety profiles and elicit statistically noninferior or superior immune responses compared to licensed (egg-based) vaccines28,29,30.

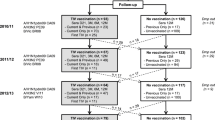

We sought to understand the impact of the timing of strain selection on vaccine match for seasonal A/H3N2 viruses. A/H3N2 is the fastest evolving subtype and has been the dominant circulating subtype for many years since its emergence in humans in 19682. Because it is not possible to recreate the expert consensus approach used by WHO computationally, we devised an alternative and reproducible vaccine strain selection method based on amino acid (AA) consensus sequences. Consensus sequences have been demonstrated to be a good predictor of future population composition for seasonal influenza viruses31 and, as used here, allow for direct objective comparison of strain selection decisions at different times while controlling for differences between the WHO’s approach and our own. In this method, we take the global consensus of A/H3N2 HA sequences collected during the two months leading up to the WHO vaccine strain selection meeting and select the most similar naturally occurring virus as the vaccine strain (Fig. 1). For example, for the northern hemisphere vaccine strain selection in February, we include global consensus A/H3N2 HA sequences collected in December and January (Fig. 1). In this way, we account for a potential one-month delay between specimen collection and the availability of sequence data to the WHO collaborating centers. For the delayed selection, this process is the same but with a three-month delay (Fig. 1). We compared historical WHO vaccine strains and the reproducibly selected strains at current and at later timing at the molecular and antigenic level with the dominant circulating strain in the influenza season for the US, Europe, and Australia and New Zealand. We found that the vaccine match could be improved by using the reproducible strain selection method while maintaining the current WHO vaccine strain selection timing, with potential further improvements if the decision could be further delayed by three months.

Results

Assessment of vaccine match

To assess the match between the WHO vaccine strain, the reproducible selection strain at WHO timing, and the reproducible selection strain at delayed timing, we first identified the dominant circulating clade of viruses for each season – from October to April for the northern hemisphere and April to September for the southern hemisphere (Fig. 1) – between 2002–2023 and 2023 for the US, Europe, Australia and New Zealand. We used the consensus of all HA sequences within the dominant clade as the dominant circulating strain for the season. We refer to the dominant circulating strain for each region and each season as the dominant strain. With the WHO vaccine strain, we refer to the vaccine strain recommended by the WHO vaccine strain selection committee. With the reproducible selection strains, we refer to 2-month global consensus sequences at either the WHO timing or the delayed timing. The timing of the reproducible selection strains will always be specified within the text.

We assessed the match of the WHO vaccine strain, the reproducible selection strain at WHO timing, and the reproducible selection strain at delayed timing (Fig. 1) against the season-dominant strain for each region based on molecular and antigenic comparisons. For the molecular comparison, we counted the number of AA differences between the dominant strain and the vaccine strain, and the reproducibly selected strains. We identified AA differences in the classically defined antigenic sites32,33,34 and in sites where substitutions have resulted in novel antigenic variants as described by Koel et al.35 (Fig. 2). For the antigenic comparison, we compared the antigenic distances between the dominant strains and the vaccine strains using antigenic cartography36. We downloaded all available HI assay data from the Worldwide Influenza Centre lab reports37 and identified antigens that were a genetic or antigenic (no mutations in the classically defined antigenic sites, in case there was no genetic match) match with the vaccine and selected strains. We reconstructed antigenic maps containing the HI antigen matches of the dominant, vaccine, and selected strains and calculated the antigenic distance between these antigens.

A Each monomer of the HA trimer consists of an HA1 (pink) and an HA2 (orange) domain. The globular head of the HA protein is predominantly made up of the HA1 domain, while the protein stalk domain is predominantly made up of the HA2 domains. The receptor binding site (RBS) (Purple) for cell attachment is located within the HA1 domain. B The five classically defined HA H3 antigenic sites are indicated as A–E32,33,34. C Sites at which mutations have resulted in the emergence of novel antigenic variants35.

Assessment of vaccine match in the United States

For the US, the median number of epitope AA differences compared to the dominant strain is six (interquartile range (IQR): 5–10; Table 1) for the WHO vaccine strain, four (IQR: 2–5) for the reproducible selection strain at WHO timing, and four (IQR: 2–6) for the reproducible selection strain at later timing. Using the reproducible selection method at WHO timing, the number of epitope AA mutations is the same in four seasons and lower in 16 out of the 21 total seasons compared to the vaccine strain (Table 2; Fig. 3). Delaying the timing by three months would further reduce the number of epitope AA mutations in three seasons (Table 2; Fig. 3). The number of mutations at novel antigenic variants positions as defined by Koel et al. is the same in 14 seasons and is reduced in seven seasons by using the reproducible method at WHO timing instead of the vaccine strain (Table 2; Fig. 3). In one season, additional reduction in AA mutations at these positions could be achieved by delayed selection (Table 2; Fig. 3). The median antigenic distance between the dominant strain and the vaccine strain is 3.0 (IQR: 2.07–4.06). This median distance to the dominant strain is lower for the reproducible strain selection method, with 2.17 (IQR: 1.06–2.58) for the WHO timing and 2.05 (IQR: 1.39–2.24) for the later timing. In four seasons, the antigenic distance to the dominant strain could be reduced by more than two antigenic units, which represents a ≥4-fold reduction in HI titers36 by utilizing the reproducible selection method compared to the vaccine strain (Table 2; Fig. 3). A ≥4-fold change in HI titer is a widely used threshold of two antigens being antigenically distinct. In 13 seasons, the difference between the antigenic distances to the dominant strain for the vaccine strain and the reproducibly selected strain at WHO timing is equal or smaller than two antigenic units, i.e., a 4-fold difference, and therefore match would have been similar (Table 2; Fig. 3). In one season an additional ≥4-fold reduction HI titers could be achieved by the delaying reproducible vaccine strain selection. Per-season results can be found in the Supplementary Information S1.

A Number of amino acid mutations in epitope sites difference relative to the dominant strain for the vaccine strain and reproducibly selected strains. B Number of amino acid mutations in sites that have resulted in novel antigenic variants difference relative to the dominant strain for the WHO vaccine strain and reproducibly selected strains. C Difference in antigenic distance to the dominant strain between the vaccine strain and the reproducibly selected strains. Pink bars indicate comparison between the dominant strain and the vaccine strain, blue bars indicate comparisons between the dominant strain and the reproducibly selected strain at WHO’s timing, and green bars indicate comparisons at delayed selection timing. Seasons for which comparison via antigenic cartography was not possible because HI tables could not be merged due to inconsistent labeling on antigens between 2004 and 2007 (see “Methods” section), and differences in the use of antivirals between 2010 and 2011 have been indicated with NA.

Assessment of vaccine match in Europe

In Europe, strains selected with the reproducible method at WHO timing resulted in a reduction in the number of AA epitope mutations in 15 out of 21 seasons, and in the same number in three seasons, reducing the median number of epitope mutations from five (IQR: 4–8) for the vaccine strain to four (IQR: 2–6) (Tables 1 and 2; Fig. 4). Delaying the timing would further decrease the median number of epitope mutations to three (IQR: 1–5), further improving four seasons (Tables 1 and 2; Fig. 4). Using the reproducible method at WHO timing the number of mutations at novel antigenic variant positions defined by Koel et al. is the same as the vaccine strain in 14 seasons and would be lower in six seasons (Table 2; Fig. 4). The number of mutations at these positions could be even further reduced in two seasons by delaying strain selection. The average antigenic distance from the dominant strain could be decreased from 3.02 (IQR: 1.46–3.96) to the vaccine strain to 1.7 (IQR: 0.66–2.13) and 1.53 (IQR: 0.53–2.17) to the reproducibly selected strains selected using the reproducible at WHO timing and later timing, respectively (Table 1). Five seasons had a 4-fold reduction in HI titers using the reproducible method at WHO timing relative to the vaccine strain, while two seasons had a 4-fold reduction through later selection (Table 2; Fig. 4). Per-season results can be found in Supplementary Information S2.

A Number of amino acid mutations in epitope sites difference relative to the dominant strain for the vaccine strain and reproducibly selected strains. B Number of amino acid mutations in sites that have resulted in novel antigenic variants difference relative to the dominant strain for the WHO vaccine strain and reproducibly selected strains. C Difference in antigenic distance to the dominant strain between the vaccine strain and the reproducibly selected strains. Pink bars indicate comparison between the dominant strain and the vaccine strain, blue bars indicate comparisons between the dominant strain and the reproducibly selected strain at WHO’s timing, and green bars indicate comparisons at delayed selection timing. Seasons for which comparison via antigenic cartography was not possible because HI tables could not be merged due to inconsistent labeling on antigens between 2004 and 2006, and differences in the use of antivirals between 2009 and 2011 have been indicated with NA.

Assessment of vaccine match in Australia and New Zealand

For Australia and New Zealand, the median number of epitope AA mutations could be reduced from six (IQR: 4–8) for the vaccine strain to four (IQR: 1–5) and two (IQR:1–4) for the strains selected with the reproducible method at WHO timing and delayed timing, respectively (Table 1). By selecting strains using the reproducible method the number of epitope mutations is lower in 20 out of 21 seasons compared to the vaccine strain and could be even further decreased in seven seasons by delaying the timing (Table 2; Fig. 5). The number of mutations in novel antigenic variant sites as defined by Koel et al. is the same as the vaccine strain in 17 seasons. Using the reproducible selection method at the WHO-recommended timing, mutations could be reduced in three seasons and further improved in four additional seasons by delaying the timing (Table 2; Fig. 5). The average antigenic distance from the dominant strain to the reproducibly selected strain was 1.89 (IQR: 1.19–3.08) at WHO timing and 0.84 (IQR:0.32–2.23) at delayed timing, compared to 2.61 (IQR: 1.79–3.14) to the vaccine strain (Table 1). In 14 seasons, the difference in HI titers from the dominant strain was smaller than 4-fold between the vaccine strain and the reproducibly selected strain at WHO timing. In three seasons, the reproducible selection strain at WHO timing resulted in a 4-fold reduction in HI titers, and in four seasons an additional 4-fold reduction in HI titers was achieved by delaying selection (Table 2; Fig. 5). Per-season results can be found in supplemental information S3.

A. Number of amino acid mutations in epitope sites difference relative to the dominant strain for the vaccine strain and reproducibly selected strains. B. Number of amino acid mutations in sites that have resulted in novel antigenic variants difference relative to the dominant strain for the WHO vaccine strain and reproducibly selected strains. C. Difference in antigenic distance to the dominant strain between the vaccine strain and the reproducibly selected strains. Pink bars indicate comparison between the dominant strain and the vaccine strain, blue bars indicate comparisons between the dominant strain and the reproducibly selected strain at WHO’s timing, and green bars indicate comparisons at delayed selection timing. Seasons for which comparison via antigenic cartography was not possible because HI tables could not be merged due to inconsistent labeling on antigens between 2004 and 2005, and differences in the species from which red blood cells were derived for the HI assay between 2007 and 2008 have been indicated with NA.

Discussion

We investigated whether delaying vaccine strain selection by three months could improve vaccine match using a reproducible strain selection approach. This theoretical exercise was primarily meant to investigate the impact of altering the timing of vaccine strain selection, not to create a new method of strain selection that should replace the WHO’s approaches. This necessitated an objective approach that allowed for direct comparison of strain selection decisions at different time points. Employing the reproducible selection method based on the global two-month HA consensus while maintaining WHO timing improved vaccine match in 43 out of 63 regional seasons based on the number of classically defined epitope mutations. Improvements were possible in 19 regional seasons when assessed by mutations at novel antigenic variant positions defined by Koel et al. and 13 regional seasons by 4-fold reductions in HI titers. Additionally, we demonstrated the added benefit by delaying selection by three months in 20 regional seasons, quantified by epitope mutations, eight regional seasons by novel antigenic variant positions, and four regional seasons by a 4-fold reduction in HI titers. The choice for the delayed timing to be three months later than currently practiced was illustrative and for demonstration purposes only.

While the reproducible strain selection method did yield improved matches in most regional seasons, there were two regional seasons when reproducibly selected strains had a larger number of epitope mutations compared to the WHO vaccine strain. Furthermore, in nine regional seasons, the reproducibly selected strains showed a greater antigenic distance to the dominant circulating strain than the vaccine strain. However, in eight of those seasons, this difference was less than two antigenic units (equivalent to a 4-fold difference in HI titers). It is important to note that reductions in the number of epitope mutations do not consistently result in 4-fold reductions in HI titers. The global consensus approach used here cannot capture all evolutionary events, and occasional mismatches naturally arise due to the stochastic and unpredictable nature of seasonal influenza evolution. WHO recommendations consider a broader range of evidence, which can lead to differences from consensus-sequence–based selections in certain seasons. Notably, the WHO postponed their 2019–2020 vaccine strain selection for A/H3N2 by a month due to lower inhibition values of emerging 3C.3a viruses38, leading to an alternative recommendation that better matched 3C.3a viruses39. However, these viruses mainly circulated in parts of Europe, whereas the 3C.2a1b virus predominated globally40. This highlights that global strain selection cannot fully anticipate which strains will dominate in different regions.

While we are not the first study to investigate the potential impact of delaying the vaccine strain recommendation, we are the first to assess the impact of later selection on vaccine match using molecular and historical antigenic data. In addition, we devised reproducible and quantitative methods to assess the vaccine match and performed our assessment on data from multiple geolocations, and found consistent results. Previous work focused on estimating the effect of a delayed recommendation on the disease burden, assuming that a delayed recommendation results in increased VE41,42. A recent study assessed the impact of delayed recommendation timing on forecasting accuracy of the clade frequencies in the subsequent influenza season and demonstrated that decreasing the forecasting horizon from 12 to three months could reduce forecasting errors by 50%43. In this study, we investigated potential improvements in vaccine match and not in VE. Although it is widely accepted that vaccine match affects VE44,45, there is limited and inconclusive evidence regarding the relationship between vaccine match and VE7,45,46,47. As such, despite demonstrating improved vaccine match using the reproducible vaccine strain selection approach, we were unable to directly relate vaccine match to VE.

Our study has limitations. First, we used an alternative vaccine strain selection method to mimic the WHO’s vaccine strain recommendation, which is based on expert consensus and includes other evidence and data sources besides sequencing and HI data that we are unable to reproduce. Second, we only considered molecular data for our vaccine strain selection, whereas the WHO vaccine strain selection committee has access to unpublished evidence, including human serology data and simple growth characteristics of strains. Human serology data does factor into vaccine strain decisions and could, to some extent, explain the different strain choices between the WHO and our reproducibly selected method. Third, while we generally expect that antigenic distance correlates with the number of epitope mutations, improved vaccine match by epitope similarity does not necessarily guarantee better vaccine match by serology since the mechanistic relationship between molecular changes and changes in antigenic phenotype is not well established. Finally, regulatory approval of seasonal influenza vaccine updates currently proceeds in parallel with the manufacturing process5,48. As such, while delayed vaccine strain selection may be viable from the manufacturing standpoint, existing regulatory processes might need to be revised to align with the shortened timeline.

Currently, vaccine strains are only updated when expert consensus suggests that they should be updated, resulting in some years with no update. Our study shows that selecting new vaccine strains every year often leads to closer matches between vaccine and circulating viruses, with further improvements possible by delaying vaccine strain selection.

Methods

Reproducible vaccine strain selection

We downloaded all available influenza A/H3N2 HA sequences and metadata that were collected from human hosts that were collected between January 1st, 2000, and December 31st, 2023, from the Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data (GISAID) (https://gisaid.org/) EpiFlu database49. Low-quality (>1% ambiguous nucleotide) and incomplete sequences (<95% sequence length of the HA1 coding domain sequence for sequences collected before 2011 or the complete HA segment from sequences collected after 2011) were removed. In addition, we also removed viruses of non-human origin, viruses identified by outlier strains based on molecular clock assumption (listed at https://github.com/AMC-LAEB/later-strain-selection/tree/main/data/outliers), and isolates with egg-based or unknown/unclear passage history labeling. Due to the limited availability of complete HA segment sequences up to the 2010–2011 (northern hemisphere) and 2011 (southern hemisphere) seasons, we used HA1 sequences for earlier seasons. From the 2010–2011 and 2011 seasons onwards, we switched to using complete HA segment sequences.

For the northern hemisphere vaccine strain recommendation that happens in February, we included all consensus sequences collected in December and January. For the southern hemisphere vaccine strain recommendation that happens in September, we included all consensus sequences collected in July and August (Fig. 1). For the later timing, we chose an arbitrary three-month delay in timing. The current vaccine strain recommendation happens approximately six months before the start of the influenza season, and with this delayed timing, it might be feasible to manufacture vaccines using next-generation vaccine platforms, as has been demonstrated for mRNA vaccines for SARS-CoV-250,51. For the northern hemisphere, the hypothetical delayed timing occurs in May, so accounting for the one-month delay in sequence data generation, we included consensus HA sequences collected in March and April for analysis. For the southern hemisphere delayed selection that occurs in December, we included consensus HA sequences collected in October and November. To minimize confusion, we refer to the (egg-based) vaccine strain recommended by the WHO vaccine strain52 selection committee as either the WHO vaccine strain or simply as the vaccine strain. With the reproducible selection strains, we refer to the 2-month global consensus sequences at either the WHO timing or the delayed timing. The timing of the reproducible selection strains will always be specified within the text.

Dominant circulating strain identification per region

To evaluate vaccine match, we inferred the dominant viral lineage circulating in each influenza season in the US, Europe for the northern hemisphere, and Australia and New Zealand for the southern hemisphere. For each regional season, we included all sequences collected in the region from clinical and cell-based samples. Sample types were determined based on passage history labels in GISAID (as detailed at https://github.com/AMC-LAEB/later-strain-selection/blob/main/scripts/labels.py). We considered sequences collected from two years before the WHO vaccine strain selection meeting to 18 months after the vaccine strain selection meeting, applicable to the region. We aligned sequences using MAFFT v7.50853 and constructed a maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree with IQ-TREE v2.2.0.354 using a general time reversible (GTR) model. We then reconstructed the temporally resolved phylogenies using TreeTime v0.11.155. This entire phylogenetic analysis pipeline has been automated using Snakemake v7.32.456 for reproducibility. To infer the dominant clade during the season, we first use PhyCLIP v2.157 to identify the clusters within the temporally resolved phylogenies. We ran PhyCLIP on the molecular clock phylogenies using a size parameter of 3, a false discovery rate (FDR) of 0.2, and a gamma of 3. Next, we identified the biggest cluster by number of sequences collected during the influenza season and took the consensus of these sequences as the representative strain of the dominant circulating clade. PhyCLIP sensitivity analyses varying the minimum cluster size and FDR parameters showed that the identified dominant strains were robust across statistically reasonable parameter ranges, with the exception of two regional seasons. In those seasons, we tested whether changes in the dominant strain altered the numbers presented in our finding and found the results remained unchanged (sensitivity analyses can be found at https://github.com/AMC-LAEB/later-strain-selection/blob/main/notebooks/sensitivity_analysis_dominant_strain.ipynb). We refer to the dominant circulating strain for each region and each season as the dominant strain throughout the main text.

Molecular evaluation of vaccine match

We quantified the vaccine match at the molecular level between the dominant strain, the WHO-recommended vaccine strain, the reproducibly selected strains at WHO timing and a later timing, by counting the number of AA mutations in the classically defined antigenic sites32,33,34, and AA mutations at positions at which mutations have been described to have resulted in novel antigenic variants (Fig. 2)35.

Antigenic evaluation of vaccine match

We assessed vaccine match on antigenic level using an antigenic cartography36. First, we downloaded all HI titer data from the HI assay data obtained from the Worldwide Influenza Centre lab reports37 (listed in csv format at https://github.com/AMC-LAEB/later-strain-selection/tree/main/data/HI_data). For each HI antigen, we identified the corresponding HA sequence in GISAID, considering all available sequences regardless of passage history while still excluding low-quality and incomplete sequences.

For each virus strain – i.e., the vaccine strains, dominant strains, reproducibly selected strains at WHO timing, and reproducibly selected strains at later timing – we identified the HI antigens that were the closest genetic match, prioritizing fewer mismatches within the antigenic sites. As there was limited data for the seasons preceding the 2010 season for the southern hemisphere and the 2011-2012 season for the northern hemisphere, we selected the antigenically closest (closest genetic match, only focusing on the antigenic sites) antigens for these early seasons. For each regional season, we then reconstructed an antigenic map. Ideally, each antigenic map should consist of a cluster of approximately five antigens representative of genetic strains for that regional season. As these antigens are organized into HI tables, we wanted to reconstruct antigenic maps by merging as few HI tables as possible, provided there were sufficient antigens. To ensure reliable maps, we only combined tables if they were measured under the same experimental conditions (i.e., same species from which the sera were derived, same species from which the red blood cells (RBCs) were derived, and same use of antivirals) and shared three or more sera. Because earlier Worldwide Influenza Centre lab reports sometimes lacked consistent labeling of ferret numbers or RBC types, we could verify whether the assays were performed under the same experimental conditions, and therefore chose not to merge those tables, resulting in the absence of antigenic comparison for some seasons. These are referred to in Figs. 3–5 in the context of inconsistent labeling. Although we aimed to limit the number of merged tables to five, in some instances, up to eight were merged when necessary to complete the antigenic map. To account for the variability from the HI assay, we reconstructed up to five antigenic maps for each regional season, depending on the number of HI antigens and the compatibility of the HI tables. Once we reconstructed the antigenic maps, we visually inspected the maps and excluded unreliable maps from further analysis. From the map coordinates, we first computed the centroids of the antigen clusters and then calculated the Euclidean distance between them. Lastly, for each regional season, we computed the median antigenic distance from the maps, and this would serve as the estimated distance between the genetic strains. All intermediate analysis files can be found at https://github.com/AMC-LAEB/later-strain-selection/tree/main.

Data availability

Code, intermediate data analysis files, and analysis output files are available at https://github.com/AMC-LAEB/later-strain-selection.

References

Iuliano, A. D. et al. Estimates of global seasonal influenza-associated respiratory mortality: a modelling study. Lancet 391, 1285–1300 (2018).

Petrova, V. N. & Russell, C. A. The evolution of seasonal influenza viruses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 16, 47–60 (2018).

Taaffe, J. et al. Advancing influenza vaccines: a review of next-generation candidates and their potential for global health impact. Vaccine 42, 126408 (2024).

Pérez-Rubio, A., Ancochea, J. & Eiros Bouza, J. M. Quadrivalent cell culture influenza virus vaccine. Comparison to egg-derived vaccine. Hum. Vaccin Immunother. 16, 1746–1752 (2020).

Weir, J. P. & Gruber, M. F. An overview of the regulation of influenza vaccines in the United States. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses 10, 354–360 (2016).

Belongia, E. A. & McLean, H. Q. Influenza vaccine effectiveness: defining the H3N2 problem. Clin. Infect. Dis. 69, 1817–1823 (2019).

DiazGranados, C. A., Denis, M. & Plotkin, S. Seasonal influenza vaccine efficacy and its determinants in children and non-elderly adults: a systematic review with meta-analyses of controlled trials. Vaccine 31, 49–57 (2012).

Lewnard, J. A. & Cobey, S. Immune history and influenza vaccine effectiveness. Vaccines 6, 28 (2018).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC seasonal flu vaccine effectiveness studies [Internet]. https://www.cdc.gov/flu-vaccines-work/php/effectiveness-studies/index.html (2024).

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Seasonal influenza, 2017–2018 [Internet]. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/AER_for_2017-seasonal-influenza.pdf (2018).

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Seasonal influenza 2018–2019 [Internet]. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/AER_for_2018_seasonal-influenza-corrected.pdf (2019).

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Seasonal influenza 2019-2020 [Internet]. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/AER_for_2019_influenza-seasonal.pdf (2020).

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Seasonal influenza 2021−2022 [Internet]. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/seasonal-influenza-annual-epidemiological-report-2020-2021.pdf (2022).

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Seasonal influenza 2022−2023 [Internet]. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/seasonal-influenza-annual-epidemiological-report-2022-2023.pdf (2023).

Kissling, E. & Valenciano, M. Early influenza vaccine effectiveness results 2015-16: I-MOVE multicentre case-control study. Eurosurveillance 21, 30134 (2016).

Valenciano, M. et al. The European I-MOVE Multicentre 2013–2014 Case-Control Study. Homogeneous moderate influenza vaccine effectiveness against A(H1N1)pdm09 and heterogenous results by country against A(H3N2). Vaccine 33, 2813–2822 (2015).

Valenciano, M. et al. Vaccine effectiveness in preventing laboratory-confirmed influenza in primary care patients in a season of co-circulation of influenza A(H1N1)pdm09, B and drifted A(H3N2), I-MOVE Multicentre Case–Control Study, Europe 2014/15. Eurosurveillance 21, 30139 (2016).

Kissling, E. et al. Influenza vaccine effectiveness estimates in Europe in a season with three influenza type/subtypes circulating: the I-MOVE multicentre case–control study, influenza season 2012/13. Eurosurveillance 19, 20701 (2014).

Kissling, E. et al. Low and decreasing vaccine effectiveness against influenza A(H3) in 2011/12 among vaccination target groups in Europe: results from the I-MOVE multicentre case–control study. Eurosurveillance 18, 20390 (2013).

Kissling, E. et al. I-MOVE multi-centre case control study 2010-11: overall and stratified estimates of influenza vaccine effectiveness in Europe. PLoS One 6, e27622 (2011).

Sullivan, S. G. et al. Pooled influenza vaccine effectiveness estimates for Australia, 2012–2014. Epidemiol. Infect. 144, 2317–2328 (2016).

Regan, A. K. et al. Intraseason decline in influenza vaccine effectiveness during the 2016 southern hemisphere influenza season: A test-negative design study and phylogenetic assessment. Vaccine 37, 2634–2641 (2019).

Fielding, J. E. et al. Effectiveness of seasonal influenza vaccine in Australia, 2015: an epidemiological, antigenic and phylogenetic assessment. Vaccine 34, 4905–4912 (2016).

Diefenbach‐Elstob, T. et al. Influenza Vaccine Effectiveness in Australia During 2017–2019. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 19, e70137 (2025).

Sullivan, S. G. et al. Heterogeneity in influenza seasonality and vaccine effectiveness in Australia, Chile, New Zealand and South Africa: early estimates of the 2019 influenza season. Eurosurveillance 24, 1900645 (2019).

Choi, Y. J. et al. Real-world effectiveness of influenza vaccine over a decade during the 2011–2021 seasons—Implications of vaccine mismatch. Vaccine 42, 126381 (2024).

Cohen Marill, M. After flu vaccine mismatch, calls for delayed selection intensify. Nat. Med. 21, 297–298 (2015).

Rudman Spergel, A. K. et al. mRNA-based seasonal influenza and SARS-CoV-2 multicomponent vaccine in healthy adults: a phase 1/2 trial. Nat. Med 31, 1484–1493 (2025).

Kandinov, B. et al. An mRNA-based seasonal influenza vaccine in adults: Results of two phase 3 randomized clinical trials and correlate of protection analysis of hemagglutination inhibition titers. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 21, 2484088 (2025).

Soens, M. et al. A phase 3 randomized safety and immunogenicity trial of mRNA-1010 seasonal influenza vaccine in adults. Vaccine 50, 126847 (2025).

Barrat-Charlaix, P., Huddleston, J., Bedford, T. & Neher, R. A. Limited predictability of amino acid substitutions in seasonal influenza viruses. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38, 2767–2777 (2021).

Wilson, I. A. & Cox, N. J. Structural basis of immune recognition of influenza virus hemagglutinin. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 8, 737–771 (1990).

Skehel, J. J. & Wiley, D. C. Receptor binding and membrane fusion in virus entry: the influenza hemagglutinin. Annu. Rev. Biochem 69, 531–569 (2000).

Wiley, D. C., Wilson, I. A. & Skehel, J. J. Structural identification of the antibody-binding sites of Hong Kong influenza haemagglutinin and their involvement in antigenic variation. Nature 289, 373–378 (1981).

Koel, B. F. et al. Substitutions near the receptor binding site determine major antigenic change during influenza virus evolution. Science 342, 976–979 (2013).

Smith, D. J. et al. Mapping the antigenic and genetic evolution of influenza virus. Science 305, 371–376 (2004).

The World Health Organization for reference and research on influenza. Worldwide Influenza Centre lab annual and interim reports [Internet]. https://www.crick.ac.uk/research/platforms-and-facilities/worldwide-influenza-centre/annual-and-interim-reports (2024).

World Health Organization. Recommended composition of influenza virus vaccines for use in the 20192020 northern hemisphere influenza season [Internet]. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/influenza/who-influenza-recommendations/vcm-northern-hemisphere-recommendation-2019-2020/201902-recommendation.pdf?sfvrsn=7aa5b685_13&download=true (2019).

World Health Organization. Addendum to the recommended composition of influenza virus vaccines for use in the 2019–2020 northern hemisphere influenza season [Internet]. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/influenza/who-influenza-recommendations/vcm-northern-hemisphere-recommendation-2019-2020/201902-recommendation-addendum.pdf?sfvrsn=cb164a4b_13 (2019).

World Health Organization. Recommended composition of influenza virus vaccines for use in the 2020-2021 northern hemisphere influenza season [Internet]. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/influenza/who-influenza-recommendations/vcm-northern-hemisphere-recommendation-2020-2021/202002-recommendation.pdf?sfvrsn=6868e7b3_21&download=true (2020).

Lee, K., Williams, K. V., Englund, J. A. & Sullivan, S. G. The potential benefits of delaying seasonal influenza vaccine selections for the northern hemisphere: a retrospective modeling study in the United States. J. Infect. Dis. 230, 131–140 (2024).

Haghpanah, F., Hamilton, A. & Klein, E. Modeling the potential health impacts of delayed strain selection on influenza hospitalization and mortality with mRNA vaccines. Vaccine X 14, 100287 (2023).

Huddleston, J. & Bedford, T. Timely vaccine strain selection and genomic surveillance improves evolutionary forecast accuracy of seasonal influenza A/H3N2. eLife 14, RP104282 (2025).

Yamayoshi, S. & Kawaoka, Y. Current and future influenza vaccines. Nat. Med. 25, 212–220 (2019).

Tricco, A. C. et al. Comparing influenza vaccine efficacy against mismatched and matched strains: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 11, 153 (2013).

Lee, J. K. H. et al. Efficacy and effectiveness of high-dose influenza vaccine in older adults by circulating strain and antigenic match: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccine 39, A24–A35 (2021).

Kelly, H. A., Sullivan, S. G., Grant, K. A. & Fielding, J. E. Moderate influenza vaccine effectiveness with variable effectiveness by match between circulating and vaccine strains in Australian adults aged 20–64 years, 2007–2011. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses 7, 729–737 (2013).

He, X., Zhang, T., Huan, S. & Yang, Y. Novel Influenza vaccines: from research and development (R&D) challenges to regulatory responses. Vaccines 11, 1573 (2023).

Shu, Y. & McCauley, J. GISAID: Global initiative on sharing all influenza data – from vision to reality. Eurosurveillance 22, 30494 (2017).

Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee. [FDA Briefing Document] Selection of Strain(s) to Be Included in the Periodic Updated COVID-19 Vaccines for the 2023-2024 Vaccination Campaign. https://www.fda.gov/media/169378/download (2023).

Bartley, J. M., Cadar, A. N. & Martin, D. E. Better, faster, stronger: mRNA vaccines show promise for influenza vaccination in older adults. Immunol. Invest 50, 810–820 (2021).

World Health Organization. Recommendations for influenza vaccine composition. https://www.who.int/teams/global-influenza-programme/vaccines/who-recommendations (2024).

Katoh, K. & Standley, D. M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 772–780 (2013).

Minh, B. Q. et al. IQ-TREE 2: new models and efficient methods for phylogenetic inference in the genomic era. Mol. Biol. Evol. 37, 1530–1534 (2020).

Sagulenko, P., Puller, V. & Neher, R. A. TreeTime: Maximum-likelihood phylodynamic analysis. Virus Evol. 4, vex042 (2018).

Köster, J. & Rahmann, S. Snakemake—a scalable bioinformatics workflow engine. Bioinformatics 34, 3600–3600 (2018).

Han, A. X., Parker, E., Scholer, F., Maurer-Stroh, S. & Russell, C. A. Phylogenetic clustering by linear integer programming (PhyCLIP). Mol. Biol. Evol. 36, 1580–1595 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all authors and contributors of the GISAID database for sharing their sequence data of influenza A/H3N2 HA sequences. In addition, we would like to thank the WHO and the Worldwide Influenza Centre at the Crick for sharing their influenza A/H3N2 HI data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.A.R. and D.R. contributed to conceptualization and methodology. A.J.H.R. contributed to formal analysis and data curation. A.J.H.R. and C.A.R. wrote the original draft. A.J.H.R., A.X.H., and C.A.R. contributed to the investigation, validation, and visualization. A.J.H.R., A.X.H., V.J.C.L., N.V., Y.P., C.A.R., and D.R. reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the submitted version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

This study was funded by Moderna. V.J.C.L., Y.P., N.V., and D.R. are employed by Moderna. C.A.R. has received consulting fees from Moderna. A.J.H.R. and A.X.H. declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

de Rooij, A.J.H., Lempers, V.J.C., Park, Y. et al. Reproducible and later vaccine strain selection can improve vaccine match to A/H3N2 seasonal influenza viruses. npj Vaccines 10, 243 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41541-025-01292-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41541-025-01292-w