Abstract

Flow virometry (FVM) can support advanced water treatment and reuse by delivering near-real-time information about viral water quality. But maximizing the potential of FVM in water treatment and reuse applications requires protocols to facilitate data validation and interlaboratory comparison—as well as approaches to protocol design to extend the suite of viruses that FVM can feasibly and efficiently monitor. We address these needs herein. First, we optimize a sample-preparation protocol for a model virus using a fractional factorial experimental design. The final protocol for FVM-based detection of T4—an environmentally relevant viral surrogate—blends and improves on existing protocols developed using a traditional pipeline-style optimization approach. Second, we test whether density-based clustering can aid and improve analysis of viral surrogates in complex matrices relative to manual gating. We compare manual gating with results obtained through algorithmic clustering: specifically, by leveraging the OPTICS (Ordering Points to Identify Cluster Structure) ordering algorithm. We demonstrate that OPTICS-assisted clustering can work as well or better than manual gating of FVM data, and can identify features in FVM data difficult to detect through manual gating. We demonstrate our combined sample-preparation and automated data-analysis pipeline on wastewater samples augmented with viral surrogates. We recommend use of this protocol to validate instrument performance prior to and alongside application of FVM on environmental samples. Adoption of a consistent, optimized analytical approach that (i) centers on a widely available, easy-to-use viral target, and (ii) includes automated data analysis will bolster confidence in FVM for microbial water-quality monitoring.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Water reuse is becoming essential to meeting water demand. Strategies for nonpotable and indirect potable reuse are well established1,2. Direct potable reuse (DPR)—i.e., reuse of water for potable purposes without an environmental buffer—represents the final frontier. While DPR offers multiple advantages3, it also engenders concerns about technical feasibility, cost, safety, and societal acceptance. The California State Water Resources Control Board concluded that improved methods of monitoring waterborne microorganisms “would enhance the understanding and acceptability of DPR” by reducing threats to human health4.

Flow cytometry (FCM) is emerging as one such method. FCM characterizes particles (including biological and non-biological targets) based on how they scatter light and/or fluoresce when passing through one or more laser beams. Improvements in instrumentation and techniques have recently enabled applications of FCM for water-quality assessment5, but key knowledge gaps persist. One major need is improved protocols for FCM-based detection and enumeration of viruses (a subset of FCM known as flow virometry, or FVM) in environmental water samples6. Researchers often struggle to differentiate actual viruses from similarly sized virus-like particles (VLPs) such as exosomes and microvesicles, and there are no widely accepted methods for performing this differentiation7. In a 2018 review, Lippé observed that absolute quantification of targets is a “persistent issue” for FVM given “lack of proper standards.” Lippé suggested that “well-characterized, fixed, and uniform viruses, particularly the more rigid nonenveloped ones, could eventually be employed as biological [flow virometric] standards.” Consistent, optimized protocols for FVM analysis of such viruses would facilitate the comparison of results and data exchange across labs8. Moreover, Dlusskaya et al. (2021) demonstrated that FVM is currently “neither sensitive nor accurate enough to quantify most natural viral populations”6. Advances in FVM hardware and dyes will be needed for FVM to detect smaller viral classes in wastewater, such as enteric viruses. But better protocols could extend the suite of viruses that can feasibly be monitored through FVM in the interim.

Brussaard et al. demonstrated9 and refined10 a staining protocol for FVM-based detection of a variety of viruses through general nucleic-acid staining. This protocol has been used and adapted by many others. However, Huang et al. (2015) reported that the Brussaard protocol did not enable clear separation of virus signal from noise in samples from a water-reclamation plant, and recommended several variations11. Brussaard et al. and Huang et al., like most researchers developing flow virometric protocols, used pipeline-type strategies12 for protocol optimization. A problem with the pipeline approach is that it overlooks potential interaction effects between factors of interest. Varying factors sequentially is also an inefficient way to identify factors with the most substantial main effects.

In addition, FVM data is typically presented by plotting the intensity and frequency of electronic signals recorded by a cytometer’s detectors. Researchers manually analyze the data by drawing gates around clusters of points and relating the gated populations to treatments and/or outcomes of interest. The success of this workflow is problematically dependent on researcher expertise. Bashashati and Brinkman (2009) found that when identical samples were analyzed via FVM by 15 experienced laboratories, the mean interlaboratory coefficient of variation ranged from 17 to 44%, with most of the variation attributed to gating differences13. Reliance on time-consuming manual gating also impedes use of FVM for real-time microbial water-quality assessment.

This study addresses both challenges. First, we leverage the Brussaard and Huang protocols to optimize the detection of T4 bacteriophage using a fractional factorial approach. T4 is widely accepted as an environmentally relevant viral surrogate, and is easy to cultivate, use, and detect through using a variety of commercially available flow cytometers. While a fractional factorial design is a well-recognized way to rigorously identify “the most important factors or process/design parameters that influence critical quality characteristics”14, the method has been surprisingly underutilized in environmental applications of FVM. Second, we test whether density-based clustering can aid and improve the analysis of viral surrogates in complex matrices relative to manual gating. We demonstrate the combined protocols on tertiary-treated wastewater samples collected from a water recycling facility and augmented with T4, and explain how the combined protocols could help improve the quality of results obtained from FVM in contexts relevant to water treatment and reuse.

Results

Optimizing staining through fractional factorial design

Our first objective was to test whether a fractional factorial experimental design can yield an improved protocol for FVM-based detection of viruses treated with a general nucleic-acid stain. We used the protocols developed by Brussaard et al. and Huang et al. as scaffolding for our design. Brussaard et al. recommended fixing the sample with glutaraldehyde at a final concentration of 0.5%, flash-freezing in liquid nitrogen, diluting in Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer, staining with SYBR Green I at a final dilution of 5 × 10–5 the commercial stock, and incubating the sample with the stain for 10 min in the dark at 80 °C. Huang et al. concluded that better results for reclaimed-water samples could be obtained by using an 0.2% glutaraldehyde concentration, omitting flash-freezing, staining at room temperature for 15 min, using SYBR Gold instead of SYBR Green I, and staining at a final dilution of 1 × 10–4. We combined treatment steps from the two protocols into a 2IV6–2 fractional factorial experimental design (replicated 4×) to assess main and interaction effects of six two-level factors—(1) stain concentration, (2) staining temperature, (3) staining time, (4) additive, (5) diluent, and (6) stain type—on nucleic-acid staining of T4 spiked into a clean matrix (either Milli-Q water or Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer) for FVM analysis. (We note that the fractional factorial design did not include all factors evaluated in the preceding studies. Our goal was to select potentially significant and applicable factors that could be optimized in the context of water reuse. Brussaard et al., for instance, observed that neither detergent addition nor citrate addition improved staining characteristics. Hence, we omitted these factors from our analysis. While Brussaard et al. found that flash-freezing improved detection of viruses, we omitted this step from the protocol because it is impractical to implement for rapid, online water-quality monitoring.)

A representative suite of results plots is displayed in Fig. 1. Collective results from the T4 optimization are also summarized graphically in Supplementary Fig. 1. A distinct target population was only visible for the eight glutaraldehyde-treated runs. Indeed, glutaraldehyde addition had a highly significant (p < 0.001) effect on total event count, mean fluorescence intensity (MFI; a measure of brightness achieved through nucleic-acid staining), and the fluorescence coefficient of variation (CV; a measure of the tightness of the target population). Adding glutaraldehyde increased the total sample event count by 65,402 events, increased MFI by 360 units, and decreased fluorescence CV by 9 percentage points.

There are three explanations for the glutaraldehyde-induced increase in sample event count:

-

(1)

Glutaraldehyde increases the presence of fluorescent phantom events (e.g., colloidal particles15).

-

(2)

Glutaraldehyde raises the fluorescence of non-target events (e.g., bacterial debris) above the fluorescence threshold.

-

(3)

Glutaraldehyde raises the fluorescence of target events (here, T4) above the fluorescence threshold.

To test (1) and (2), we used FVM to compare untreated and glutaraldehyde-treated 0.2-μm filtered phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) after staining with SYBR Gold. We also compared FVM data collected on untreated and glutaraldehyde-treated samples of the negative control (bacterial host propagated and purified without virus infection) stained with SYBR Gold. In neither case did FVM reveal a distinct target population, nor a substantial increase in event count, after glutaraldehyde addition. These results suggest that glutaraldehyde addition not only helps visibly separate the target signal from non-target events, but also increases the absolute number of target events detected through FVM. The target event count for the eight runs that incorporated glutaraldehyde was approximately 109–1010 events/mL: about an order of magnitude greater than the qPCR-based titer (108–109 gc/mL) and about two orders greater than the culture-based titer (107–108 PFU/mL). These discrepancies may be attributed to factors such as non-specific staining of particles (e.g., cellular debris) in FVM, losses during DNA extraction in PCR, and aforementioned challenges with plate-based culturing.

The fractional factorial design enabled the quantification of main and two-way interaction effects for each factor tested. Results are shown in Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 1. We performed this quantification first on all events within the analysis bounds. Though the quantification analysis suggested the presence of numerous significant main effects as well as several significant two-way interaction effects between glutaraldehyde and other experimental factors, results were compromised by the fact that the analysis did not distinguish between target and non-target events. Because a distinct target population was only visible for glutaraldehyde-treated runs, and because our goal was to develop a staining protocol that most successfully separates the target population from the background, we also performed the quantification using only data from target events identified in glutaraldehyde-treated runs.

No statistically significant two-way interaction effects were observed in the target-only analysis. However, including glutaraldehyde as a variable in the experimental design meant that only a small subset of two-way interaction effects between non-glutaraldehyde factors was analyzed. Future work could explore other possible two-way interaction effects. The target-only quantification analysis also did not identify any statistically significant main effects on MFI. Diluent was the only variable that had a significant main effect on event count: the main effect of using TE buffer instead of MQ water was –7807 events with a p value of 0.023. This result may be explained by the increased tendency of free stain to form colloids in low-ionic-strength water16.

Stain temperature and diluent had strongly significant (p < 0.001) main effects on CV. Staining at 50 °C decreased CV by 2.7 percentage points; using TE buffer decreased CV by 4.4 percentage points. Stain concentration had a strongly significant (0.001 < p < 0.01) effect on CV: staining at 1 × 10–4 times the sample volume increased CV by 1.8 percentage points. Stain time and stain type both had significant (0.01 < p < 0.05) main effects on CV. Staining for 15 min decreased CV by 1.2 percentage points; staining with SYBR Gold rather than SYBR Green I increased CV by 1.5 percentage points. We conclude that stain temperature and diluent are the most important sample-preparation factors besides glutaraldehyde addition. In other words, dilution in TE buffer and staining at 50 °C meaningfully increases the tightness of the T4 fluorescence signal, thereby aiding discrimination of T4 from the background.

We also conclude that using SYBR Green I (instead of SYBR Gold) and staining for 15 min (instead of 1 min) could improve target discrimination of T4 slightly further. But these small potential gains must be weighed against drawbacks. Staining for 1 min is more conducive to near-real-time FVM analysis than staining for 15. Moreover, SYBR Green I exhibits a large fluorescence enhancement upon binding to DNA but not RNA. A protocol using SYBR Green I will be less effective than SYBR Gold at detecting a wide variety of viruses, since the latter exhibits a large fluorescence enhancement upon binding to DNA and RNA. Future work could explore these tradeoffs for environmental samples.

Overall, our results suggest that a protocol for reliably identifying and quantifying T4 bacteriophage through FVM involves a combination of treatments recommended by Brussaard et al. and Huang et al. We recommend diluting the sample in TE buffer to achieve an FVM analysis rate of about 102–103 events/s, adding glutaraldehyde at a final concentration of 0.5%, and staining with SYBR Green I at 5 × 10–5 times the sample volume at 50 °C for at least 1 min.

Automating data analysis through density-based clustering

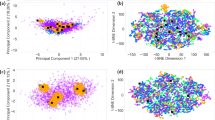

Our second objective of this study was to explore cluster analysis as an objective, automated alternative to manual gating. Specifically, we tested whether density-based clustering can aid and improve the analysis of viral surrogates in complex matrices. The OPTICS algorithm developed by Ankerst et al. (1999) underlies the most widely used density-based clustering strategies17. OPTICS outputs all points in a dataset ordered by a characteristic reachability distance, and generates a reachability plot that can be used to identify clusters by looking for valleys of low-reachability distance separated by peaks of noise. The most straightforward way to extract clusters from the reachability plot is to set a single global reachability threshold. Unfortunately, this approach fails when—as is often the case in real-world environmental samples—the number of targets and the spatial density of FVM data generated by those targets is variable (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Alternative options are (i) extracting clusters via a manual selection of peaks and valleys on the reachability plot, or (ii) using an algorithm to perform the selection automatically (Supplementary Fig. 3). Ankerst et al. suggested extracting clusters automatically by identifying “steep up” and “steep down” areas on the reachability plot characterized by the ξ steepness parameter, but ξ must be laboriously tuned based on trial and error. The opticskxi package available in R18 provides a variant cluster-extraction algorithm that “iteratively investigates the largest differences” in steepness until either a given number of clusters are defined or the maximum number of iterations is reached19. We compared results obtained through manual gating to results obtained through OPTICS combined with either manual or opticskxi-based cluster extraction for two datasets, as described below. We note that the nature of FCM analysis makes validating results at the single-particle level difficult if not impossible. Results are therefore typically evaluated by comparing bulk target counts/concentrations obtained through FCM to the same obtained through other methods (e.g., electron microscopy, culturing, qPCR).

A variety of microbiological targets may be present and of interest in a real-world setting such as a water-treatment plant. To test whether density-based clustering can accurately detect and quantify waterborne viruses alongside other specimens, we prepared a solution of TE buffer containing known concentrations of viral and non-viral targets in the submicron size range. The targets were φ6 and T4 bacteriophages as well as fluorescent polystyrene beads of 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8 μm in diameter. T4 was included as an environmentally relevant viral surrogate that generates a clear FVM signal; φ6 was included to represent viral classes that are not detectable through FVM as distinct populations but may still generate an indeterminate VLP signal6; and beads were included because they are highly uniform and similar in size to many viral and bacterial classes. Combining biological and engineered targets enabled us to test the performance of density-based clustering on a mixed-density dataset. We collected FVM data on 10 replicates of each of the five dilutions of the mixed-target solution. The 0.8-μm bead component was kept undiluted as a control/reference.

Figures 3, 4 and 5, respectively, illustrate results from manual gating, OPTICS ordering + manual extraction, and OPTICS ordering + opticskxi-based extraction of the mixed-target data (additional results for OPICS ordering + manual extraction or + opticskxi-based extraction are available in Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5). We note several features of the results. First, manual extraction labeled far more points as noise than did opticskxi. This is because for manual extraction, we separated valleys from peaks by setting cutpoints at the apparent knees of the reachability plot curves. Opticskxi, by contrast, tends to set cutpoints at or near the curve peaks.

Representative results for additional dilutions are available in Supplementary Fig. 4. Panel a plots show the OPTICS ordering of the data from which the clusters were manually extracted. Colors highlight each manually extracted cluster. Panel b plots visualize the data as SSC vs. FITC plots, with points colored based on the cluster extraction. Cluster colors are consistent between the two plots for each dilution, but not necessarily between different dilutions.

Representative results for additional dilutions are available in Supplementary Fig. 5. Panel a plots show the OPTICS ordering of the data from which the clusters were algorithmically extracted. Colors highlight each algorithmically extracted cluster. Panel b plots visualize the data as SSC vs. FITC plots, with points colored based on the cluster extraction. Cluster colors are consistent between the two plots for each dilution, but not necessarily between different dilutions.

Second, the different data-analysis strategies yielded somewhat different clusters. In manual gating, we drew six gates: one for each of the three bead sizes, T4, φ6 and other VLPs, and an additional apparent cluster corresponding to 0.5 μm bead doublets. (A doublet occurs when two particles pass through the interrogation laser beam of a flow cytometer simultaneously.) Neither manual extraction nor opticskxi identified a cluster matching the manual gates drawn for φ6/VLPs and for the 0.5 μm doublet. Manual extraction tended to identify events falling within these gates as noise, while opticskxi- tended to assign events falling into the φ6/VLP gate as part of the T4 cluster and events falling into the 0.5 μm doublet gate as part of the 0.5 μm bead cluster. Both OPTICS-based approaches frequently detected two separate clusters within the side scatter (SSC) vs. fluorescence (FITC) region designated by manual gating as corresponding to 0.2 μm beads. Inspecting the data revealed that some of the events exhibiting the same SSC and FITC signal intensity ranges exhibited meaningfully different FSC signal intensities.

To numerically compare results across the different data-analysis approaches, then, we established four “buckets” corresponding to (1) viruses (including T4, φ6, and other VLPs), (2) 0.2 μm beads, (3) 0.5 μm beads (including 0.5 μm doublets), and (4) 0.8 μm beads. Supplementary Tables 2 and 3 show expected and average detected event counts across the three approaches for each bucket; Fig. 6 plots these data. There were clear differences between the theoretical and detected event counts for each bucket. Event counts were higher than expected for the 0.2 and 0.5 μm bead buckets, slightly lower than expected for the 0.8 bead bucket, and much lower than expected for the virus bucket. The bead-bucket discrepancies can be explained by the fact that manufacturer-provided concentrations of the bead solutions were only approximate within an order of magnitude. Discrepancies for the virus bucket can be explained by the fact that φ6, a small and difficult-to-stain enveloped virus, emits only a faint FITC signal. A majority of the φ6 particles spiked into the mixed-target solution were likely not stained brightly enough to rise above the FITC limit of detection6.

Focusing on detected event counts, results were generally consistent across all three data-analysis approaches for the bead buckets. For the virus bucket, event counts from manual gating and opticskxi were similar to each other but generally higher than event counts from manual extraction. This is because while engineered particles generate tightly grouped data of fairly uniform density, viral targets tend to generate more unevenly dispersed FVM data. Consider how each of our three data-analysis approaches considered handle the clusters associated with T4 and φ6. For manual gating, we established relatively large T4 and φ6 gates. Any point falling within these gates was hence categorized as part of the virus bucket. For the OPTICS-based methods, there was not a clear shift in reachability distance marking the transition from T4 to φ6/VLPs: reachability distance increased gradually towards the border of the T4 cluster, then increased at roughly the same rate as the T4 cluster border bled into the φ6/VLP region. This resulted in manual extraction and opticskxi delivering divergent results. Opticskxi tended to assign high-reachability-distance points included in a given reachability curve (points near the peak) to the same cluster as low-reachability-distance points (points near the valley). Since OPTICS placed many points corresponding to the T4 and φ6/VLP regions on the same reachability-plot curve, opticskxi assigned those points to the T4 cluster. By contrast, manually set cutpoints assigned points near the valley of the T4/φ6/VLP curve to the T4 cluster and points near the peak to noise.

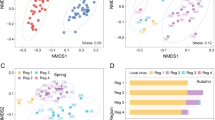

We performed a modified version of the mixed-target experiment to assess whether automated clustering can accurately detect and quantify waterborne viruses in a challenging environmental matrix, where the presence of an increased background signal could confound FVM analysis and/or alter the target signal. (For instance, adherence of viral particles to suspended solids in wastewater (Chahal et al. 2016) could decrease event count; or uptake of stain by the natural virus community in wastewater could reduce T4 fluorescence intensity by reducing dye available for target staining.) Specifically, we spiked a T4/bead solution described above into tertiary-treated, 0.2-μm-filtered wastewater effluent diluted 10×. The T4/bead solution was the same as the one used in the mixed-target experiment, but with φ6 and 0.5 μm beads omitted. We also prepared an identical but unspiked solution for comparison. We again collected FVM data on 10 replicates each of the spiked and unspiked solutions, analyzing data by both manual gating and density-based clustering.

Figures 7, 8, and 9 illustrate results from manual gating, OPTICS ordering + manual extraction, and OPTICS ordering + opticskxi-based extraction of environmental-spike data. Manual gating identified the three targets: n 0.8 μm bead cluster, n 0.2 μm bead cluster, and for the T4-spiked sample, and a T4 cluster partially obscured by signal from the wastewater matrix but still clearly within the previously established T4 gate. Expected event counts were roughly in line with detected event counts obtained through manual gating, exhibiting the same discrepancies observed in the mixed-target experiment (Supplementary Table 4). We also observed a low-SSC, high-FITC cluster in most of the replicate runs for both the T4-spiked and unspiked samples. The identity of particles in this cluster is unknown.

Panel a plots show the OPTICS ordering of the data from which the clusters were manually extracted. Colors highlight each manually extracted cluster. Panel b plots visualize the data as SSC vs. FITC plots, with points colored based on the cluster extraction. Cluster colors are consistent between the two plots for each of the T4-spiked and unspiked experiments, but not necessarily across experiments. Some clusters are not visually apparent on the scatterplots because they include low-SSC points collapsed onto the y-axis.

Panel a plots show the OPTICS ordering of the data from which the clusters were algorithmically extracted. Colors highlight each algorithmically extracted cluster. Panel b plots visualize the data as SSC vs. FITC plots, with points colored based on the cluster extraction. Cluster colors are consistent between the two plots for each of the T4-spiked and unspiked experiments, but not necessarily across experiments. Some clusters are not visually apparent on the scatterplots because they include low-SSC points collapsed onto the y-axis.

The two OPTICS-based clustering approaches yielded quite different results. As was also true for the mixed-target experiments, manual cluster extraction successfully detected the 0.8 μm bead cluster, the 0.2 μm bead cluster, and often a sub-cluster in the 0.2 μm bead zone corresponding to particles exhibiting similar FITC and SSC intensities but different FSC intensities. Manual extraction also detected one or more clusters in the low-FITC, low-SSC region corresponding to φ6/VLPs in the mixed-target experiments, and hence to background (including natural virus particles) in the wastewater matrix. Manual extraction did not typically clearly distinguish the T4 cluster, nor did it detect the low-SSC, high-FITC foreign cluster.

For opticskxi-based cluster extraction, the constraining k parameter meant that opticskxi did not yield as many clusters as manual extraction. Rather, opticskxi consistently detected n 0.8 μm bead cluster, a cluster that included the 0.2 μm beads but also many apparent noise points, and a cluster that included the T4/VLP/background region. The latter sometimes spilled over to include much of the 0.2 μm bead region. Opticskxi occasionally detected the higher-FSC sub-cluster in the 0.2 μm bead region, occasionally detected the low-SSC, high-FITC foreign cluster, and never detected a clearly distinct T4 cluster.

Because (i) the reachability plots from the environmental-spike data were so complex, (ii) we set manual gates exclusively based on the SSC vs. FITC pseudocolor density plot (i.e., without considering FSC), and (iii) of concerns (discussed further below) that OPTICS might over-weight FSC signal intensities for virus data, we also generated OPTICS orderings of the environmental-spike data using only the SSC vs. FITC dimensions. Supplementary Figs. 6 and 7 contain representative plots illustrating manual extraction and opticskxi results, respectively, using these reduced-dimension orderings. The reachability plots of these orderings were simpler but did not yield significantly better results, especially for detecting T4.

Discussion

As advanced water treatment and reuse becomes more common, the need for improved methods of monitoring waterborne microorganisms is becoming more acute. FCM—and its virus-focused specialty, FVM—is emerging as one such method. But realizing the full potential of FVM in applications relevant to water treatment and reuse requires consistent, optimized protocols to facilitate data validation and interlaboratory comparison—as well as approaches to protocol design that can extend the suite of viruses that FVM can feasibly and efficiently monitor.

In this study, we proposed using fractional factorial experimental designs for optimizing FVM sample-preparation protocols, and density-based clustering for analyzing complex FVM data. Both approaches can be considered for any FVM application but were here demonstrated using the bacteriophage T4 in the context of water treatment and reuse. Specifically, we used a fractional factorial experimental design to efficiently identify multiple factors with statistically significant main effects on T4 count, MFI, and CV. Our results suggest an optimized protocol for FVM-based T4 detection that blends and improves on protocols developed using a traditional optimization approach. While we did not observe any statistically significant interaction effects among factors tested, employing a fractional factorial design enabled us to confirm the absence of such effects.

In this study, we showed that density-based clustering can sometimes work as well or better than manual gating of FVM data—and is certainly far faster and less labor-intensive. In particular, we found that OPTICS ordering coupled with either manual or opticskxi-based cluster extraction delivered excellent results for the dense, well-defined clusters generated by engineered beads. There was almost unilaterally good agreement between results obtained through manual gating and density-based clustering for bead targets. In addition, both OPTICS-assisted approaches revealed a feature of the data not detected through manual gating: that some points within the apparent 0.2 μm bead region in fact emitted meaningfully different FSC signals.

Results from applying the different data-analysis methods to virus targets were more mixed (strengthening the case for using both biological and non-biological standards to facilitate validation and comparison of FVM data across labs). Manual gating reliably identified separate T4 and φ6/VLP populations, but these manual gates impose unnaturally sharp boundaries on irregularly shaped clusters and are incapable of adjusting to variability in biological data (e.g., due to inconsistent staining). However, neither manual cluster extraction nor opticskxi reliably identified separate T4 and φ6/VLP populations in this study. In the mixed-target experiment, manual extraction reliably identified the T4 cluster while labeling points in the φ6/VLP region as noise. This is arguably acceptable since the apparent φ6/VLP events constitute a vague cloud of points more than a clearly defined cluster. In the environmental-spike experiment, though, manual extraction failed to identify spiked T4. Opticskxi grouped apparent T4 points with points in the φ6/VLP/background region in both the mixed-target and the environmental-spike experiments. This is also arguably acceptable if the ultimate intended application is monitoring total virus counts. On the other hand, opticskxi applied to data from the environmental-spike experiment sometimes unacceptably grouped T4 with 0.2 μm beads.

We conclude the discussion with a candid assessment of applications and limitations. The optimized protocol developed in the first portion of this study focused on a single target (the bacteriophage T4) suspended in a clean solution, in a controlled laboratory setting. As such, we emphasize that this protocol is not intended as a one size fits all tool for detecting waterborne viruses. Rather, per Lippé (2018), we recommend that other researchers working on FVM for microbial water-quality monitoring consider adopting our protocol as a routine validation step when performing FVM experiments with non-specific staining of nucleic acids in environmental samples. The protocol is freely available at https://www.protocols.io/view/an-optimized-protocol-for-flow-virometry-fvm-based-4r3l2onjqv1y/v1. As stated above, T4 is widely accepted as an environmentally relevant viral surrogate, and is easy to cultivate, use, and detect through using a variety of commercially available flow cytometers. Incorporating analysis of T4, suspended in clean matrix, as a routine part of any FVM experiment will help researchers determine instrument-specific limits of detection and expected ranges of viral signal intensities while also facilitating interlaboratory comparisons. We further recommend that researchers couple this analysis with an analysis of standard but non-biological viral surrogates (e.g., submicron-scale fluorescent polystyrene beads) to generate multiple comparison points for data across different labs. Finally, we recommend that to carry out these analyses as objectively as possible, researchers consider employing computational techniques such as clustering.

In addition, while the second portion of this study demonstrates the potential of automated data-analysis pipelines for FVM and FCM in water-treatment and water-reuse applications, further work is clearly needed to improve performance of density-based clustering on challenging FVM data from targets like viruses in challenging matrices like wastewater. Future work could focus, for instance, on selecting the best OPTICS parameters based on information available about the dataset in question, improving automatic cluster extraction, or more strategically weighting different dimensions of FVM data in OPTICS. (The dimensionality reduction employed in OPTICS may inappropriately assign different data dimensions equal weight. For instance, T4 and φ6 stained with SYBR Gold both exhibit FCM signals that rise above instrument noise on the FITC dimension (T4 more than φ6), but not the FSC or SSC dimensions. Weighting FITC more strongly may therefore yield more accurate results for clustering virus-generated FCM data. Indeed, it is possible that equal weighting of all dimensions contributed to challenges we encountered using density-based clustering to distinguish between T4 and φ6.) OPTICS could also be useful as a tool to assist manual gating in complex samples. A researcher could theoretically apply density-based clustering on a target in a clean sample, and then use the identified cluster boundary as a gate for complex samples where density-based clustering fails.

Such additional work is merited given the advantages that density-based clustering could offer for microbial water-quality assessment. First, density-based clustering could improve result consistency. We previously found that “data from identical samples can produce electronic signals of considerably different intensities depending on the instrument used for analysis”20. Labs using different instruments cannot readily adopt a shared set of analytical gates, but they can adopt a shared clustering algorithm. Second, the method could improve the speed at which results are delivered. By minimizing human involvement in data processing, density-based clustering analysis could support real-time validation of microorganism removal in advanced water treatment4. Third, the method could improve result accuracy—essential to positioning FVM as a viable quality-check mechanism in water-reuse applications with public-health implications. Fourth and finally, the approach could improve result quality by uncovering features in FVM data difficult to detect through manual gating alone.

Methods

Phage stock preparation

The bacteriophage T4 (ATCC 11303-B4) and its host Escherichia coli (Migula) Castellani and Chalmers (ATCC 11303) were ordered from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and propagated from freeze-dried specimens. φ6 bacteriophage (strain HB104) and its host Pseudomonas syringae were provided as stock solutions by Samuel Díaz-Muñoz (UC Davis). Host aliquots (containing 25% glycerol by volume) and phage aliquots were stored at –80 °C until use. The purified, high-titer phage stocks used in this study were prepared using protocols based on Bonilla et al. (2016)21 (see Supplementary Methods). Negative control stocks were prepared using the same protocols minus the phage spike. One group of positive and negative stock aliquots was prepared by 100× dilution in Milli-Q (MQ) water; a second was prepared by 100× dilution in Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer. Subsets of each group were fixed with glutaraldehyde (0.5% final concentration, 15 min at 4 °C). Final stock aliquots were stored at –80 °C until use.

Phage stock quantification

We assessed the titers of the purified stock via both plate-based culturing and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR)/real-time qPCR (RT-qPCR) (see Supplementary Methods). Approximate phage stock titers are reported in Supplementary Table 5. The Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments (MIQE) checklist for this study is included as a separate file in the Supplementary Information.

Flow cytometric analysis

Working stocks of SYBR Green I and SYBR Gold stains (both obtained from ThermoFisher Scientific as 10,000× concentrates in dimethyl sulfoxide) were prepared in advance by dilution in TE buffer and stored in aliquots at –20 °C until use. FVM analysis was carried out using the 488 nm (blue) solid-state laser on a NovoCyte 2070V Flow Cytometer coupled with a NovoSampler Pro autosampler (Agilent). Green fluorescence (FITC) intensity was collected at 530 ± 30 nm; forward and side scatter (FSC and SSC) intensities were collected as well. In all experiments, a 10-μL volume of each sample was measured using the lowest instrument flowrate (5 μL/min) and a FITC = 800 threshold. For the optimization experiments, 10 μL of an unstained control was run after each sample. The instrument was flushed in between each sample and control by running 150 μL of 1× NovoClean solution (Agilent) followed by 150 μL of MQ water through the SIP at the highest instrument flowrate (120 μL/min). Instrument performance was ensured by performing the instrument’s built-in quality control test at least monthly.

Optimization design and protocols

We created a 2IV6–2 fractional factorial design to assess main and interaction effects of six two-level factors on nucleic-acid staining of T4 for FVM analysis. Table 1 summarizes the factors and factor levels tested in the optimization experiment, with corresponding rationales. For these experiments, previously prepared T4 stock aliquots (see above) were thawed immediately before each round of testing and diluted an additional 10× in the appropriate medium prior to staining. Samples were incubated in the dark following stain addition; incubation at higher temperatures was performed by immersion in a water bath.

Supplementary Table 6 presents the matrix of experiments included in the design. Factors were strategically assigned to avoid confounding main effects with interaction effects thought likely to prove significant. Corresponding estimation structures are provided in Supplementary Table 7, with main effects and two-way interaction effects in bold. Four complete rounds of the experimental design were performed; run order was randomized within each round.

Optimization data analysis

The number of events in control (unstained) samples was subtracted from the number of events in the corresponding stained samples. Data were bounded at 0 ≤ SSC ≤ 1000 and 800 (threshold level) ≤FITC ≤ 10,000 and visualized using FlowJoTM 10 software (Becton Dixon & Company) as pseudocolor density plots to assess whether a distinct target population was visible. The software’s “Create Gates on Peaks” function was used to set the bounds of the target population on FITC for these runs, after which the number, MFI, and CV of all target particles were calculated. The FrF2 package was used in Rstudio Desktop (version 2021.09.01) to quantify main and two-way interaction effects of each factor tested in the optimization. Documentation for this package is available at https://www.rdocumentation.org/packages/FrF2/versions/2.1/topics/FrF2 package. The FrF2 analysis was performed first on all events from all runs, and second on target events from glutaraldehyde-treated runs.

Mixed-target and environmental-spike data generation

Previously prepared stock phage (T4 and φ6) solutions were treated using the optimized protocol described in the main text, albeit with SYBR Gold instead of SYBR Green I as the staining agent given that φ6 is an RNA virus. 20 μL of T4 stock (10–3 dilution) and 20 μL of φ6 stock (10–3 dilution) were added to 1 μL of an 0.2-μm diameter fluorescent polystyrene bead suspension, 2 μL of an 0.5-μm diameter bead suspension, and 15 μL of PBS. 2×, 4×, 8×, and 16× dilutions of this mixed-target solution were also generated. 4 μL of an 0.8-μm diameter bead suspension was added to each dilution as a constant-concentration reference.

Separately, tertiary-treated effluent from the UC Davis Wastewater Treatment Plant (collected as a grab sample, transported to the lab on ice, stored at 4 °C, and used within 24 h of collection) was syringe-filtered at 0.2 μm, diluted 10× in Milli-Q water, and spiked with the same mixed-target solution described above, minus the φ6 and 0.5 μm beads. Ten replicates of each solution dilution were analyzed via FVM as described above. Supplementary Table 2 provides the expected concentrations of each target in the mixed-target and environmental-spike solutions per effective volume (10 μL) analyzed.

Mixed-target and environmental-spike data analysis

Manual gating was performed on experimental data from the 1× mixed-target dilution experimental data plotted as SSC vs. FITC log-log scale pseudocolor density plots. Set gates were then applied to the remaining mixed-target and environmental-spike data. Density-based clustering was performed as follows. We applied a log transformation to the FSC, SSC, and FITC data collected from each replicate, then standardized the features by centering and rescaling to standard deviation 1. We used Rstudio (version 2021.9.1.372) to apply the OPTICS implementation available in the dbscan package (Hahsler et al. 2019). Distance between points was measured using Euclidean distance. Based on Sander et al. (1998), we set k equal to 2*[dimensionality of the dataset], or 6 in this case We set ε equal to 0.1 to bound the algorithm and reduce computational time. We used MATLAB® software (version R2021a; MathWorks) to inspect reachability plots of the OPTICS-ordered data for manual extraction. We applied the opticskxi package available in R (Charlton 2019) for automated extraction, using a maximum iteration number of 1000 and a maximum cluster number (k) of six for the mixed-target data and four for the environmental-spike data. For the mixed-target data, the minimum-points-per-cluster (MinPts) parameter started at 8000 for the 1× dilution and was halved for each subsequent dilution. For the environmental-spike data, MinPts was set at 8000. k for the mixed-target data was selected based on the number of clusters identified through manual gating; k for the environmental-spike data was selected based on the three clusters identified through manual gating, plus a fourth to provide the algorithm room to identify a cluster corresponding to the background in the wastewater matrix. The MinPts parameters were selected based on the lowest expected target event count.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Data are available at https://doi.org/10.25338/B8PW6X.

Code availability

Analysis scripts are available at https://github.com/hsafford/FCMClustering2022.

References

National Research Council. Water Reuse: Potential for Expanding the Nation’s Water Supply through Reuse of Municipal Wastewater (National Academies Press, Washington, DC, 2012).

Olivieri, A. et al. Evaluation of the Feasibility of Developing Uniform Water Recycling Criteria for Direct Potable Reuse. https://www.waterboards.ca.gov/drinking_water/certlic/drinkingwater/documents/rw_dpr_criteria/app_a_ep_rpt.pdf (2016).

Arnold, R. G. et al. Direct potable reuse of reclaimed wastewater: it is time for a rational discussion. Rev. Environ. Health 27, 197–206 (2012).

California State Water Resources Control Board. Investigation on the Feasibility of Developing Uniform Water Recycling Criteria for Direct Potable Reuse. waterboards.ca.gov/drinking_water/certlic/drinkingwater/documents/rw_dpr_criteria/final_report.pdf (2016).

Safford, H. R. & Bischel, H. N. Flow cytometry applications in water treatment, distribution, and reuse: a review. Water Res. 151, 110–133 (2019).

Dlusskaya, E., Dey, R., Pollard, P. C. & Ashbolt, N. J. Outer limits of flow cytometry to quantify viruses in water. Environ. Sci. Tech. Water 1, 1127–1135 (2021).

Reyes, J. L. Z. & Aguilar, H. C. Flow virometry as a tool to study viruses. Methods 134–135, 87–97 (2018).

Lippé, R. Flow virometry: a powerful tool to functionally characterize viruses. J. Virol. 92, e01765–17 (2018).

Brussaard, C. P. D., Marie, D. & Bratbak, G. Flow cytometric detection of viruses. J. Virol. Methods 85, 175–182 (2000).

Brussaard, C. P. D. Optimization of procedures for counting viruses by flow cytometry. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70, 1506–1513 (2004).

Huang, X. et al. Evaluation of methods for reverse osmosis membrane integrity monitoring for wastewater reuse. J. Water Process Eng. 7, 161–168 (2015).

Nescerecka, A., Hammes, F. & Juhna, T. A pipeline for developing and testing staining protocols for flow cytometry, demonstrated with SYBR Green I and propidium iodide viability staining. J. Microbiol. Methods 131, 172–180 (2016).

Bashashati, A. & Brinkman, R. R. A survey of flow cytometry data analysis methods. Adv. Bioinformatics 2009, 584603 (2009).

Antony, J. 7 – Fractional factorial designs. In Design of Experiments for Engineers and Scientists (Elsevier, 2016).

Dlusskaya, E. A., Atrazhev, A. M. & Ashbolt, N. J. Colloid chemistry pitfall for flow cytometric enumeration of viruses in water. Water Res. X 2, 100025 (2019).

Zhang, Y. et al. The influence of ionic strength and mixing ratio on the colloidal stability of PDAC/PSS polyelectrolyte complexes. Soft Matter. 11, 7392–7401 (2015).

Ankerst, M., Breunig, M. M., Kriegel, H.-P. & Sander, J. OPTICS: ordering points to identify the clustering structure. ACM SIGMOD Rec. 28, 49–60 (1999).

Charlon, T. opticskxi_ OPTICS K-Xi Density-Based Clustering. R Package Version 0.1 (2019).

Chalron, T. opticskxi_ OPTICS K-Xi Density-Based Clustering. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/opticskxi/vignettes/opticskxi.pdf (n.d.).

Safford, H. R. & Bischel, H. N. Performance comparison of four commercially available cytometers using fluorescent, polystyrene, submicron-scale beads. Data Brief. 24, 103872 (2019).

Bonilla, N. et al. Phage on tap–a quick and efficient protocol for the preparation of bacteriophage laboratory stocks. PeerJ 4, e2261 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation under Award R18AC00106. We are grateful for the following UC Davis core resource centers for support on various aspects of the work: the Real-Time PCR Research & Diagnostics Core Facility, the Flow Cytometry Shared Resource, and the DataLab. We are also grateful to the following individuals: Yutong Zhang and Erica Koopman-Glass for assistance with laboratory tasks, Bridget McLaughlin and Jonathan Van Dyke for flow cytometry training, David Rocke for advising on fractional factorial experimental design, Edlin Escobar and Minji Kim for helping develop the qPCR protocols, Jonathan Herman for early assistance with cluster analysis, and Nick Ulle and Pamela Reynolds for later help on cluster analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.R.S. helped guide the experimental design, performed the bulk of laboratory work, oversaw project components related to cluster analysis, and drafted the manuscript. M.M.J. performed supplemental laboratory work, provided insight into cluster analysis, and helped revise the manuscript. H.N.B. served as PI for the project as a whole and helped revise the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Safford, H.R., Johnson, M.M. & Bischel, H.N. Flow virometry for water-quality assessment: protocol optimization for a model virus and automation of data analysis. npj Clean Water 6, 28 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41545-023-00224-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41545-023-00224-2