Abstract

The main chemical, ecotoxicological, and environmental fate characteristics of cyanide, along with its treatment methods for cyanide-contaminated wastewater, were thoroughly examined. A global biogeochemical cycle of cyanide is proposed, covering the key physicochemical processes occurring in aqueous, soil, and atmospheric environments. The principles, advantages, and disadvantages of various treatment methods—including chemical, physicochemical, electrochemical, photochemical, and biological approaches—are evaluated. Finally, the feasibility of reusing cyanide waste is explored.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cyanide has long been recognized as one of the deathliest poisons throughout human history1. It was not until Stewart and MacArthur discovered its potential as a gold ore leaching reagent2 that cyanide found one of its most prevalent modern-day uses. For over a century, the anionic “free” form of cyanide (CN−) has been employed in gold extraction due to its exceptional efficiency and low cost2,3.

Despite this long history with cyanide in mining, the chemical industry is the largest consumer, utilizing over 80% of the cyanide produced annually2. It is used to produce organic materials such as nylon, nitrile, adhesives, plastics, paints, solvents, enamels, herbicides, pesticides, and fungicides2,4. Additionally, it is widely used in metallurgy, jewelry manufacturing, and certain pharmaceutical processes4,5. Only 20% of global cyanide production is allocated to the manufacture of sodium cyanide, of which 90% is consumed in gold mining operations, making up 18% of the world’s cyanide production2.

Unfortunately, all cyanide-consuming industries generate aqueous cyanide wastes because of incomplete cyanide consumption or production of cyanide derivatives. Furthermore, cyanide is often produced as a by-product in industries that do not intentionally utilize it, such as coal, coke, and petroleum production6. As a result, vast volumes of cyanide-containing wastewater are generated daily. Like many human-derived wastes, these effluents are ultimately discharged into the environment. Given cyanide’s notorious toxicity for humans, plants, and animals—as well as its long-term persistence in the environment7—it is crucial that all wastewaters containing cyanide undergo treatment processes to minimize its environmental impact; particularly when it may enter potable water supplies.

In the early days of cyanide waste management, effluent dilution was widely practiced due to its simplicity and low cost8. However, as cyanide was not broken down into less toxic products, it remained prone to accumulating in ground and surface waters through natural processes. As a result, dilution was eventually replaced by chemical oxidation methods, such as alkaline chlorination and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) degradation8,9. In time, more efficient, less polluting, and cost-effective methods emerged based on physicochemical, biological, and electrochemical principles9. Nevertheless, with each new method, unique constraints surfaced, requiring further refinement and adaptation. Consequently, research continues to this day in search of methods that offer the best balance between advantages and limitations.

Success in these efforts depends on a deep understanding of cyanide’s chemistry, its environmental fate, and the core principles of wastewater treatment. While much of this knowledge is scattered across research papers and extensive book chapters, a consolidated and comprehensible overview remains absent.

Hence, this review presents cyanide’s chemistry and ecotoxicological characteristics as starting points for understanding cyanides’ behavior in wastewaters and nature, accompanied for the first time by an integral cyanide’s biogeochemical cycle to assess its interactions while moving from wastewater sources to the different environmental matrices. Once underlying chemical processes have been addressed, an illustrative overview of the fundamental principles underpinning cyanide’s wastewater treatment methods is presented for a feasible understanding, as these aspects comprehension is essential for the design of effective treatment strategies. Additionally, this review synthesizes the latest insights (5 years past) into cyanide wastewater treatment methods, highlighting their advantages and disadvantages.

Cyanide’s chemistry

Cyanides encompass a variety of compounds featuring a carbon atom triply bonded to the nitrogen atom (–C≡N) moiety in their structure10,11, occurring either as an anion (i.e., inorganic cyanides) or as a covalent functional group (i.e., nitriles)11.

Inorganic cyanides can generally be classified into free cyanide and complex cyanide. Free cyanide typically includes anionic cyanide (CN−) and hydrogen cyanide (HCN), both of which are highly reactive towards various elements and molecules. Due to cyanide’s filled “s” and “p” orbitals, and its empty “d” and “f” orbitals, it can share its triple bond electrons with oxygen and sulfur, forming cyanate (OCN−) and thiocyanate (SCN−) anions. Moreover, cyanide can establish π-acceptor bonds similarly to halides and can also act as a strong nucleophile in addition reactions, playing a critical role in many biological processes12.

Both CN− and HCN exist in an acid-base equilibrium. The HCN/CN− pair has a pKa of 9.24 at 25 °C, meaning that HCN will predominantly exist at a pH below 9.24, while anionic CN− will prevail at pH values above 9.2412,13. This species distribution, however, can shift with temperature changes. Lower temperatures tend to hinder the dissociation of HCN into CN−, thereby favoring the presence of HCN12. HCN is typically gaseous due to its poor solubility in water and high vapor pressure (KH = −2.8 (Henry’s constant))14.

In its anionic form, cyanide can act as a ligand, often forming coordination complexes with transition metal cations. Cyanide establishes σ-bonds with the metal’s empty d-orbitals by donating electron pairs, and it can also establish π-bonds by accepting electron density from the metal into its empty anti-bonding orbitals12,15. As a result, a variety of metal-cyanide complexes can form, exhibiting varying levels of stability.

These metal-cyanide complexes are commonly classified into weak and strong complexes. Weak metal-cyanide complexes, typically involving cadmium, zinc, silver, copper, nickel, and mercury cations, dissociate under mildly acidic conditions (pH 4–6)12 due to their moderate stabilization constants (Ks)16. On the other hand, strong complexes, involving cobalt, platinum, gold, palladium, and iron cations, require strongly acidic conditions (pH < 2) for dissociation12,17, owing to their higher Ks values16.

Free and complexed cyanides are also prone to oxidation reactions. Under neutral to alkaline pH conditions and in the presence of an oxidizer, anionic cyanide can be converted to cyanate (OCN−)12. Similarly, when cyanide dissociates from metal complexes, oxidation to cyanate can occur. However, due to the strong binding in certain metal-cyanide complexes, the cyanide ligands are less likely to undergo oxidation compared to their weak counterparts.

Whether free or complex, inorganic cyanide can be found in different aqueous and solid states in the environment18, predominantly associated with anthropogenic activities. Even so, they also naturally occur primarily as HCN19. HCN is produced by certain bacteria, fungi, plants, and even insects20,21, as part of their metabolic processes. Although the precise mechanism of HCN synthesis has not been elucidated for every organism, it is generally well understood in prokaryotes and cyanogenic plant species.

Particularly, when referring to bacteria, genera such as Alcaligenes, Aeromonas, Bacillus, Pseudomonas, and Rhizobium are known to have the ability to produce HCN22,23. These rhizosphere bacteria utilize the enzyme HCN synthase—encoded by the hcnABC gene cluster—to convert glycine found in soil pore water and root exudates into HCN and carbon dioxide21,24.

In contrast, plants produce cyanide via the ethylene biosynthesis pathway. Ethylene, an important regulatory phytohormone, is derived from the oxidation of 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC) by the enzyme ACC oxidase (ACO). During this process, cyanide is released as a by-product25,26. Cyanide also exists in plants as cyanogenic glycosides18,19—sugar-bonded cyanides—which can release HCN through enzymatic action27. These secondary metabolites, commonly found in cyanogenic plants, are primarily derived from amino acids such as L-leucine, L-valine, L-tyrosine, L-isoleucine, L-phenylalanine, or cyclopentenyl-glycine28,29. The biosynthesis of cyanogenic glycosides involves a multi-step process catalyzed by two multi-functional cytochrome P450 enzymes, leading to the formation of unstable hydroxynitriles, which are subsequently glycosylated by soluble cytosolic glucosyltransferases29.

The resulting concentration of plant cyanide compounds varies considerably depending on factors including plant section, maturity, time, and growing conditions27. Moreover, several commonly consumed plant goods have been found to contain cyanide molecules, including cassava, sorghum, corn, almonds, apricots, peaches, plums, bamboo shoots, sprouted beans, cherries, olives, potatoes, soybeans, nuts, and coffee beans30,31.

Ecotoxicological characteristics

Cyanide’s toxicity in nature depends on its chemical form. In aqueous or atmospheric media, cyanide is largely found as free cyanide, which is its most toxic form32, particularly for humans and animals. This high toxicity is due to cyanide’s ability to inhibit crucial metabolic processes33.

In humans, free cyanide forms stable complexes with essential metalloenzymes19,34, such as cytochrome oxidase, an enzyme involved in ATP synthesis. By inhibiting the function of cytochrome oxidase, cyanide disrupts cellular respiration35,36, leading to central nervous system depression and respiratory failure2,31. Additionally, cyanide binds to iron in the blood, inhibiting oxygen transport, and causing asphyxiation37.

In contrast, plants have evolved enzyme-meditated detoxification mechanisms to mitigate cyanide toxicity. These processes dampen cyanide’s harmful effects by converting HCN to less toxic compounds38,39,40. For example, β-cyanoalanine synthases (β-CAS) convert HCN into β-cyanoalanine by combining it with cysteine. Alternatively, the enzyme rhodanese converts cyanide into thiocyanate39,40. Furthermore, when cyanide is found within organic molecules (e.g., cyanogenic glycosides, cyanolipids), it shows reduced toxicity41.

Similarly, cyanide’s oxidized derivatives, such as thiocyanate and cyanate, which are also present in aqueous environments, are significantly less toxic than free cyanide41. For example, thiocyanate is approximately seven times less toxic than cyanide42, while cyanate’s toxicity is reduced by a factor of 100043,44.

Further reductions in toxicity occur when cyanide forms coordination complexes with transition metals41. The toxicity of these complexes depends on their stability constants (Ks) and solubility product constants (Ksp). A higher Ks indicates stronger binding and reduced dissociation of cyanide, thereby lowering its inherent toxicity. Meanwhile, lower Ksp describes complexes with reduced solubility, which may precipitate out of solution and exhibit diminished toxicity. For example, [Fe(CN)6]3− and [Fe(CN)6]4− complexes are 1000 times less toxic than free cyanide. When precipitation occurs, as with Prussian blue (Fe4[Fe(CN)6]3), toxicity decreases by a factor of 195016.

Environmental fate: cyanide biogeochemical cycle

Cyanide fate in nature should not be regarded as a linear manner with a starting and ending point, but rather as an interconnected system of complex reactions and interactions involving various cyanide species in atmospheric, aqueous, and soil media. As such, the Cyanide biogeochemical cycle study approach is strongly recommended instead.

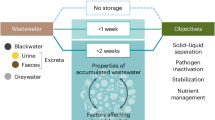

It was first described by Mudder in 1984 and has since been referenced consistently in more recent works45. Mudder’s Cyanide’s Cycle depicts the main physiochemical processes cyanide undergoes in the Mining Tailings Model, as illustrated in Fig. 1. Thus, this cycle focuses on cyanide’s environmental fate as a by-product of mining activities; especially those involving gold extraction through cyanidation processes46.

However, cyanide’s fate extends beyond mining tailings, encompassing other researched scenarios such as the Atmospheric Chemistry of Hydrogen Cyanide, Bushey’s Cyanide’s fate mechanisms on wetlands, and Cyanide’s cycle in nature itself. Therefore, this review aimed to integrate these three scenarios into a comprehensive discussion of cyanide’s biogeochemical cycle. To the best of our knowledge, such a joint exploration of these scenarios has not been carried out yet.

Cyanide’s biogeochemical cycle begins within the “mining tailings” segment (Fig. 1), where mining-derived cyanide-rich residues from extraction processes are produced (e.g., gold extraction)2. Once these residues are discharged in tailing ponds, they separate into two distinct phases: an upper aqueous phase and a lower phase comprising solid tailings in slurry form47. Between these two phases and the atmospheric one, cyanide undergoes one of eight processes: volatilization, oxidation, radical oxidation, photolysis, hydrolysis, precipitation, complexation, or sorption48.

Cyanide’s volatile nature derives from its low solubility in water and high vapor pressure (reaction 1), where it behaves as a weak acid (HCN) (reaction 2)13,14. Thus, cyanide’s transport is facilitated throughout the atmosphere (Fig. 1), resulting in a lengthy atmospheric residence time (approximately five months)49,50. Particularly, HCN has no major role in tropospheric chemistry49; instead, in the stratosphere, HCN can undergo radical oxidation and/or photolysis reactions, which serve as principal sinks for atmospheric HCN49. Radical oxidation reactions include HCN oxidation by hydroxyl radicals (·OH) and singlet oxygen (O(1D))49,51 (reactions 2 and 3, respectively), while photolysis reactions involve the ultraviolet-mediated photolysis of HCN, which only occur in the upper stratosphere (reaction 4)49,51.

Despite HCN’s limited water solubility, if dissolved by rainfall or in any body of water, including the tailings pond of its origin, it undergoes acid-base equilibria (reaction 5), leading to the formation of aqueous cyanide anions (CN−). These anions gain mobility in water and have the potential to reach nearby land environments.

Within the aqueous phase of the tailings pond, cyanide chemistry is governed by several processes, including hydrolysis, thiocyanates formation, complexation, and biological oxidations45. The first two processes result in the less toxic formate and ammonium ion (reaction 6), as well as SCN− (reaction 7). In terms of complexations, cyanide readily forms complexes with different metals (reaction 8), primarily with ferric (Fe3+) or ferrous (Fe2+) ions (reactions 9 and 10)45.

All the aforementioned cyanide species can undergo subsequent biological oxidation (reactions 11–13), including the anionic (CN−) itself (reaction 14). In addition, secondary processes, such as biological nitrification (reaction 15), could occur as part of aerobic microorganisms’ metabolic activity14. Similarly, aqueous CN− or HCN in solid tailings can also be used by anaerobic microorganisms to fulfill metabolic requirements, resulting in additional reactions (reactions 16–21)14.

Additional reactions involving cyanide species in aqueous solution include precipitation reactions. As mentioned, cyanide readily forms coordination complexes, particularly ferricyanide ([Fe(CN)6]3−) and ferrocyanide ([Fe(CN)6]4−) complexes. Under specific stoichiometric conditions, these complexes, previously discussed, can precipitate as insoluble salts of iron, copper, nickel, manganese, lead, zinc, cadmium, tin, or silver45. Most commonly, in the case of iron (II) ions, ferrocyanide complexes precipitate as the well-known coordination compound Prussian blue (reaction 22)45.

If precipitation does not occur, aqueous ferric and ferrous complexes can undergo further reactions. Under the influence of incident ultraviolet light, typically coming from sunlight, these complexes can undergo photolytic reactions, leading to ligand loss. These reactions commonly yield iron-cyanide complexes with reduced oxidation states and free cyanide (reactions 23 and 24)52, which can subsequently go through the rest of the processes.

Up to this point, this examination of cyanide’s chemistry has been described within the limits of a tailings pond that has kept its integrity. However, tailings ponds’ linings are prone to ruptures and thus may seep liquid tailings directly into the soil. Despite the frequency of such incidents, they have yet to be incorporated into existing cyanide cycle frameworks, even when they have been repeatedly reported53,54,55,56. Further, in addition to the aforementioned reactions, sorption processes can also occur with remaining aqueous cyanide species in tailings ponds. These species are commonly absorbed by ferric hydroxide and manganese hydroxide particles, as well as clays46.

Similarly, cyanide’s environmental fate beyond tailings ponds has been overlooked in previous cycles, neglecting the likely event that the pond’s contents are discharged untreated into water bodies. Indeed, research has highlighted numerous cases of liquid tailings and associated wastewater being discharged without proper treatment, whether intentionally57,58,59,60,61 or because of spill incidents62,63. Consequently, aqueous cyanide species are allowed to freely migrate into external aquatic environments.

The second segment of the biogeochemical cycle includes Wetland section (Fig. 1), reported by Bushey in 200346. In this segment, free cyanide, ferric, and ferrous cyanide complexes are absorbed by plants and assimilated through their metabolism46. This process involves the biosynthesis of cyanogenic glycosides, secondary metabolites derived from amino acids, which plants employ in their defensive mechanisms against herbivores and other organisms64,65. Synthesized within the plant cytoplasm, these glycosides can undergo enzymatic hydrolysis into HCN, which is released as a chemical defense response66. Other processes that may occur in this segment include reactions between soil organic compounds and cyanide, resulting in the formation of compounds such as acetonitrile (Me-CN) or other nitrile solids67.

Finally, the third segment of the cycle (Fig. 1) encompasses all processes and interactions involving cyanide with plant and animal species. As previously noted, cyanide is typically assimilated by plants to produce cyanogenic glycosides. These compounds can indirectly enter animal organisms through the consumption of cyanide-containing plants, as in the case of livestock68,69,70. Through this mechanism, animals metabolize plant cyanogenic glycosides, leading to the bioaccumulation of cyanide in their tissues. When they die, cyanide returns to the soil as free cyanide or various nitrogen-containing compounds46. Once in the soil, free cyanide and other soluble cyanide species may be transported through water-assisted leaching or react with metal ions and remain in the soil as insoluble salts (precipitates)14. Consequently, soluble cyanide species may continue their journey until reaching the water table through a very slow kinetic mobility process14. Cyanide that infiltrates groundwater may persist in soluble form and migrate within the groundwater or undergo precipitation and mineralization processes, depending upon existing ions14,71.

Cyanide wastewater treatment methods

When cyanide is present in the primary environmental matrices, it poses a critical threat to human health, as well as to aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems. Therefore, cyanide’s toxic nature calls for its removal from environmental matrices, particularly from water sources. Hence, environmental legislation across countries has established permissible levels of cyanide concentration in aqueous media. For instance, the US EPA has set a maximum level of cyanide concentration in water for human drinking purposes at 0.2 mg L−1 72. If cyanide is to be discharged into freshwater bodies, the maximum allowed concentration is capped at 22 µg L−1, while for continuous discharge, it is 5.5 µg L−1 73.

To comply with these quality standards, cyanide requires effective removal treatment processes whose selection depends on a series of factors. First, the type of wastewater must be considered, as cyanide concentration heavily depends on it. For instance, concentrations range from ≤100,000 mg mL−1 in electroplating baths6, 10–1000 mg mL−1 coke plants6,16, 50−500 mg L−1 in noble metal ore processing16, 0.5–144 mg L−1 in petroleum refining74, to 5–10 mg L−1 in coal gasification processes75. These variations determine the specific treatment approach. Conventional chemical and physicochemical methods are effective for high cyanide concentrations, whereas novel alternatives like biological treatments are better suited for lower cyanide concentrations (e.g., microbial degradation for 0–10 mg mL−1)16. Additionally, pretreatment may be necessary for certain wastewaters, such as stripping ammonia from coking plant waters76.

Second, the composition of the effluents must be assessed, as not all treatment methods are effective for different cyanide species. For wastewaters primarily composed of free cyanide and weak acid dissociable complexes, conventional chemical and physicochemical treatments are appropriate. However, for effluents containing strong metal-cyanide complexes, physicochemical methods are preferred due to the complexes’ resistance to oxidation76. The presence of other chemical entities also requires consideration. Free metal ions can mask and stabilize cyanide species, while dissolved organic matter increases the chemical oxygen demand, potentially competing with cyanide for oxidative treatments77.

Third, the current technological readiness of treatment methods must be evaluated. While newer approaches such as phytoremediation, ozonation, UV-oxidation, or electrochemical advanced oxidation processes show promise, many remain in the research or pilot stage, with few reaching commercial scale like carbon adsorption processes76.

Lastly, cost considerations are critical in selecting a treatment method. Historically, alkaline chlorination has been widely used for cyanide removal despite its high cost9,78,79, which has driven the development of newer, more efficient, and cost-effective methods. A green approach has also emerged, emphasizing the reduction of toxic by-products, economization of reagents, and minimization of energy consumption as important factors when selecting the optimal treatment solution.

Methods principles

Cyanide removal from wastewater is generally achieved using five main treatment methods, each operating on distinct principles: chemical, physicochemical, electrochemical, photochemical, and biological. The following sections provide a concise yet comprehensive overview of these methods, aimed at enhancing clarity and understanding.

Chemical methods

Chemical treatment methods for cyanide wastewater involve reactions that convert cyanide into less toxic derivatives48. Among multiple reaction pathways, oxidation reactions are often preferred. As outlined in the biogeochemical cycle, while cyanide typically undergoes oxidation reactions through biological pathways, with the appropriate oxidizing agent, reactions can be performed without the intervention of living beings (i.e., microorganisms).

Conventionally, cyanide wastewater has been treated through alkaline chlorination48. At a pH of 1180, this process involves the oxidation of aqueous cyanide by liquid chlorine (Cl2) or hypochlorite ions (ClO−) to form cyanogen chloride (CNCl), which subsequently hydrolyzes into the less toxic cyanate ion (OCN−) (Fig. 2). Typically, an excess of chlorine is used to further oxidize cyanate48. While alkaline chlorination offers numerous advantages, such as its ability to treat a wide range of cyanide concentrations48, important drawbacks include the high consumption of chlorine, resulting in high operational costs, hazardous chlorinated by-products (e.g., CNCl), and reduced oxidation efficacy for certain cyanide-metallic complexes48. Nevertheless, precipitation reactions present viable alternatives to oxidation methods. Notably, cyanide precipitation by iron (II) ions, as discussed in the biogeochemical cycle, stands out, as it can reduce cyanide concentration up to 1–5 mg L−1. Furthermore, it does not require strong basic conditions; slightly acidic conditions (pH = 5–6) are preferred48.

Alkaline chlorination process with the use of chlorine gas or hypochlorite ions as oxidants80.

As the use of alkaline chlorination has declined over time, alternative oxidations reactions have gained prominence. Typically used ones employ H2O2 as an oxidizing agent, albeit in combination with other substances. In the Caro’s acid process, before cyanide oxidation can take place, H2O2 needs to react with concentrated sulfuric acid (H2SO4) to form peroxymonosulfuric acid (H2SO5), also known as Caro’s acid48,81. This compound is responsible for oxidizing cyanide into OCN−48,82 (Fig. 3). This process is frequently preferred for treating tailings slurry48.

Main reactions involved in the Caro’s acid process48.

Alternatively, if H2O2 is used independently, metallic catalysis is required. By using aqueous copper (II) ions cyanide’s oxidation by H2O2 is facilitated (Fig. 4). This catalytic process also applies to cyanide-metallic complexes, wherein metallic ions later precipitate as their corresponding hydroxides, typically at a pH of 9–9.548. Similarly, copper (II) ions serve as catalysts when cyanide is oxidized by sulfur dioxide (SO2)48 or any reduced sulfur salt (i.e., metabisulfite)82 in the presence of oxygen (O2) gas (Fig. 4).

Cyanide oxidation reactions involved in the copper-catalyzed H2O2 process and the sulfur dioxide and air process48.

In general, Caro’s acid process and SO2 oxidation method are preferred for treating cyanide solid tailings, whereas H2O2 and SO2 (to some extent) are commonly used to treat liquid tailings48. As in alkaline chlorination, their main disadvantages are the generation of toxic by-products, which is inherent to chemical treatment processes83; with some exceptions.

Namely, ozonation has recently gained attention in treating cyanide-containing wastewater. Specifically, it stands out based on cyanide intense reactivity with ozone and its complete degradation, without unwanted by-products generation84. In general, cyanide ozonation proceeds by hydroxyl radicals produced upon ozone hydroxide-ion catalyzed decomposition, in water84,85. Once these radicals are produced, they oxidize cyanide to cyanate, which can be degraded by further ozonation or additional hydrolysis reactions. Normally, a 90% removal is expected when ozone is administered in a 1–1.2 mol O3/mol CN− dose84.

Physicochemical methods

In contrast to chemical methods for treating cyanide wastewater, physicochemical methods offer the advantage of avoiding the generation of toxic by-products. Among these methods, adsorption processes are notable for their ease of operation, high efficiency, and cost-effectiveness86,87,88. Nonetheless, as a major drawback, physicochemical methods do not eliminate contaminants from their original source. Instead, they simply transfer the pollutants to another medium for further treatment and eventual discharge89.

In principle, adsorption occurs as a surface phenomenon in which an adsorbate (in this case, cyanide) interacts with an adsorbent or substrate, becoming attached to it90. If this interaction occurs via intermolecular forces, physisorption takes place; if chemical bonds are established, chemisorption occurs90. In either case, a wide variety of low-cost absorbent materials are available for this purpose, both natural or synthetic (organic or inorganic)91.

Generally, in cyanide removal, physisorption is the preferred mechanism, as adsorbent recovery is desired; however, ongoing research is exploring chemisorption. Activated carbon (AC) is by far the most frequently used absorbent for cyanide removal, primarily because of its exceptional adsorptive and catalytic properties92. In addition to adsorbing cyanide species, AC can catalyze their oxidation to less toxic forms, such as OCN–92. Nevertheless, studies have indicated that AC alone may not achieve optimal removal efficiency, necessitating surface modifications92.

It has often been noted that AC removal efficiency can be improved by impregnating it with different metals92,93. The use of copper (i.e., Cu2+ ions) is typically favored over other metals due to its oxidizing effect on cyanide (i.e., catalytic oxidation). Briefly, when Cu2+ ions are impregnated on AC, free cyanide readily forms metallic complexes that get adsorbed on the AC surface. There, cyanide undergoes early oxidation to cyanogen, and subsequently to cyanate94.

Similar results have been found for metallic oxides impregnated AC’s surfaces93. Alternatively, surface modification can be achieved by incorporating organic moieties or functional groups that can enhance cyanide removal92. For instance, functional groups containing protonated carbonyl have been found to facilitate electrostatic anion complexation with cyanide95. Additionally, bacterial biofilms can be impregnated onto the AC surface; these absorb and biodegrade cyanide through metabolic/enzymatic process20,92,96. This aspect will be discussed in the context of biological methods for cyanide wastewater treatment.

In addition to AC, other commonly used absorbents include raw and modified zeolites97,98,99,100, as well as new bioadsorbents. These alternatives offer similar advantages to AC in terms of low cost, effectiveness, and ease of use and are commonly found in food or plant waste/by-products101,102,103,104,105.

Electrochemical methods

In general, the electrochemical degradation of cyanide wastewater relies on the use of an electrochemical cell, comprising an anode, cathode, and electric power source, wherein cyanide undergoes an oxidation process. This principle has spurred the development of multiple electrochemical techniques to effectively oxidize cyanide. While differing in approach, they all share the ability to remove pollutants from aqueous media, even at low concentrations, as has been reported for cyanide (<500 mg L−1)106.

Overall, electrochemical techniques excel in generating less harmful by-products107, particularly when compared with the toxicity and risk factors of the target pollutant. However, the exception is when by-products are of a halogen nature (i.e., Cl− or Br− oxidation by-products)108. Other advantages include their non-selective character and strong oxidizing capabilities109. Their primary limitation is their high energy consumption110,111, especially when used at a large scale110.

The simplest electrochemical techniques for cyanide degradation constitute direct and indirect electrooxidation methods. In direct oxidation, cyanide is oxidized at the anode, while in the cathode, heavy metals present in the cyanide wastewater are reduced106,112 (Fig. 5). This process is usually preferred for treating cyanide in high concentrations (>1000 mg L−1)106. Conversely, indirect oxidation uses a “non-active” anode to generate strong oxidizing species113, which facilitates the oxidation of cyanide in solution, particularly at low concentrations (<500 mg L−1)106. For instance, when sodium chloride is added to the electrolytic media as an electro-active supporting electrolyte, cyanide is oxidized by hypochlorite anions (ClO−) generated in the anode106,114 (Fig. 5).

Catalytic reactions for cyanide oxidation using Cu-impregnated activated charcoal (Cu-AC)94.

In both scenarios, platinum or graphite electrodes are predominantly used as anodes106. However, when more reactive metals are used as anodes, electrocoagulation is then possible. This technique involves the use of a cation-generating anode, typically iron or aluminum115. Once released into the solution, these cations facilitate the precipitation of cyanide as insoluble coordination complexes (e.g., Prussian blue) (Fig. 5).

Other novel alternatives have explored the possibility of reducing cyanide by electrocatalysis instead of the usual electrooxidation pathway. Although implausible, considering the strong electrostatic repulsion between anions (e.g., CN−) and the negatively charged cathode, enhancing the binding ability of the cathode to overcome repulsion has been proposed. For instance, when transition metal oxides (e.g., Co3O4) are used as cathode, polarization under an electric field can foster the cathode’s cyanide enrichment116. Consequently, cyanide reduction is made possible. After the reduction products have been generated, they can experience further oxidation processes.

In addition to the discussed techniques, contemporary research has shifted focus toward electrochemical advanced oxidation processes (EAOPs). This method involves the electric generation of hydroxyl radicals (·OH)117, primarily derived from water108. As one of the strongest known oxidizers (+2.8 V vs. standard calomel electrode, pH 0)117,118, hydroxyl radicals play a crucial role in the oxidation processes. Owing to their rapid reactivity and non-selective behavior, they effectively degrade a wide range of contaminants118,119, including cyanide. Typical mechanisms for generating hydroxyl radicals in EAOPs include water anodic oxidation, anodic oxidation with electrogenerated H2O2, and Electro-Fenton-related processes120,121. Among these, the first mechanism is particularly suitable for degrading cyanide, as it operates in alkaline conditions, thereby preventing HCN generation during cyanide oxidation (Fig. 6).

Even though cyanide requires high alkaline conditions to avoid HCN evolution, while it oxidizes to cyanate, low alkaline conditions are simultaneously desired to ensure efficient cyanate hydrolysis122. Although contradictory, Electro-Fenton-related processes can successfully overcome this obstacle. For instance, it has been reported cyanide can be directly mineralized to NO3− via heterogeneous Electro-Fenton generated ·OH and ·O2− radical oxidation122.

Photochemical methods

Like the EAOPs, the photochemical approach to cyanide degradation also involves the generation of oxidizing radicals, but this only occurs because of incident electromagnetic radiation. Specifically, only ultraviolet radiation (UV light) can generate said radicals, either from oxidizing agents or catalysts118. When these oxidizing radicals, used to remove a particular pollutant, are produced by exposing oxidizers (e.g., H2O2, O3, or Cl2)123 to incident UV light, the process is known as photooxidation.

Conversely, when oxidizing radicals are generated on the surface of a photo-activated catalyst, typically of a semiconducting nature, the corresponding process is referred to as photocatalysis. In this case, radicals can form from photogenerated electron-holes pairs (hν+vb), in the semiconductor valence band, which has oxidizing capacity, and from excited electrons (e−cb) in the respective conduction band, which have reductive capacity118,124. Through these mechanisms, several reactive oxygen species (ROS) are produced, such as superoxide (•O2−), hydroxyl radicals (•OH), and singlet oxygen (O(1D))89.

As previously mentioned, strongly oxidizing hydroxyl radicals are preferred for cyanide degradation, which is commonly produced using a titanium oxide (TiO2) catalyst124 (Fig. 7).

Whether employing a photooxidation or photocatalytic approach, cyanide undergoes oxidization to form cyanate. However, while the former involves a simple radical reaction125, the latter entails a photocatalytic process utilizing electron-hole pairs within the photocatalyst126.

Biological methods

In recent years, biological treatment of cyanide wastewater has gained popularity among other treatment alternatives, including physical or chemical processes. This approach utilizes microorganisms to remove pollutants from water in a simple, cost-effective, and robust manner127. In the case of cyanide, biological methods can reduce its concentration in wastewater to environmentally acceptable levels while also producing fewer harmful by-products48. Thus, biological treatment is regarded as an optimal alternative.

Biological treatment methods range from phytoremediation to microbial bioremediation. Phytoremediation involves the use of plants to remove or reduce cyanide concentrations in water or soil, as plants can utilize cyanide to fulfill their nitrogen needs128 (Figs. 9a). Conversely, microbial bioremediation relies on the metabolic activities of bacteria, fungi, or microalgae to degrade cyanide129,130. These microorganisms use cyanide as a source of nitrogen131, thus breaking it down through one or more enzymatic pathways83,131,132 (Fig. 9b). Bacterial strains from the genera Pseudomonas, Bacillus, and Klebsiella, among others, have been examined in the bioremediation of free cyanide and metallic-complexed cyanide133.

Photochemical reactions behind cyanide’s photocatalytic oxidation with TiO2 catalyst126.

a In phytoremediation, plants remove or reduce cyanide in water or soil by using it as a nitrogen source. b In microbial bioremediation, bacteria, fungi, or microalgae can metabolize cyanide, thereby degrading it132.

Even though the above-mentioned bacteria are capable of degrading cyanide, they are still susceptible to its toxicity and that of their derivatives. In general, aerobic bacteria degrade active cyanide via nitrogen metabolism (ammonification−nitritation−nitrification) at the cost of free cyanide toxic inhibition16,134. If complexed with Fe2+ and Fe3+ ions, free cyanide toxic inhibition on aerobes can decrease134; nonetheless the metallic protection on cyanide can pose metabolic difficulties due to the complexes’ stability134. On the other hand, anaerobic bacteria are more prone to degrade cyanide complexes (exhibiting lower toxicity) to cyanate and formamide via cyanide metabolic enzymes despite these complexes’ chemical stability16,134.

It has also been found that bimetallic binding on iron-cyanide complexes can foster cyanide release, and hence allow microbial metabolization. For example, [Fe(CN)6]4– complex interaction energy (Eint) with Cu+, Cu2+ or Ag+ (i.e., respectively, −0.7, −0.59, −0.68 a.u.) suggests this metals can set free cyanide ligands for microbial degradation, on the contrary to Fe3+, Co2+ and Ni2+ (i.e., respectively, −2.70, −1.55, −1.57 a.u.)134.

In addition, research on bacterial-mediated bioremediation has expanded into the burgeoning field of environmental omics, particularly in the context of environmental pollution and remediation technologies, known as cyanomics. Like other omics technologies, research on cyanomics provides useful information on genes, mRNA, sRNA, and metabolites associated with microorganisms capable of removing cyanide from polluted media through their metabolic activities135. In terms of cyanotrophic bacteria, cyanomics has enabled the identification of genes and proteins involved in cyanide resistance, as well as those in cyanide degradation, opening possibilities of screening for cyanide-related genes in other bacterial genomes through comparative genome analysis135.

Furthermore, its essential to emphasize that most state-of-the-art methods are centered on enzymatic processes involved in bacterial-mediated cyanide degradation136. Among these methods, preferred strategies often include the isolation of new bacterial strands from contaminated media that are capable of degrading cyanide, as well as the extraction of bacterial enzymes to use as catalysts in biodegradative reactions. Other related emerging cyanide bioremediation methods include electrochemical-based methods such as electro-bioremediation (EK-Bio) for in situ remediation, microbial fuel cell technologies, and anaerobic cyanide biodegradation in small reactor setups, with additional biogas formation83.

Innovations in cyanide wastewater treatment

For a more comprehensive understanding of these treatment methods, this review examines the latest research pertaining to each technique, clarifying their fundamental principles and associated strengths and limitations (Table 1).

Future directions

Given the persistent threat posed by cyanide’s high toxicity and ongoing use, research on mitigating its impact is being carried out in several scientific areas. The pursuit of the most efficient and cost-effective degradation methods remains paramount. Consequently, novel methodologies will continue to be developed with the aim of achieving maximum reduction of this pollutant in water, while ensuring economic viability.

While the removal of cyanide from wastewater remains the primary objective, it is worth considering the potential value of cyanide waste in different industries. For instance, cassava residues (which contain a significant amount of cyanide) from the agro-industry could be repurposed to produce biosurfactants or biogas137,138, thereby offering products with lesser environmental impact. Similarly, cyanide residues produced in gold mining operations could be used for new extraction processes, presenting an economically viable alternative for purchasing cyanide for gold mines139,140. Numerous other scenarios wherein cyanide is produced as waste warrant further investigation.

References

Cope, R. B. Acute cyanide toxicity and its treatment: the body is dead and may be red but does not stay red for long. In: Handbook of Toxicology of Chemical Warfare Agents, 373–388. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-819090-6.00025-8 (2020).

Hilson, G. & Monhemius, A. J. Alternatives to cyanide in the gold mining industry: what prospects for the future? J. Clean. Prod. 14, 1158–1167 (2006).

Azizitorghabeh, A., Mahandra, H., Ramsay, J. & Ghahreman, A. Gold leaching from an oxide ore using thiocyanate as a lixiviant: process optimization and kinetics. ACS Omega 6, 17183–17193 (2021).

Dzombak, D., Ghosh, R. & Wong-Ching, G. Manufacture and the use of cyanide. In: Cyanide in Water and Soil. Chemistry, Risk and Managment, 41–55 (CRC Press Taylor & Francis Group, Boca Raton, 2006).

Bhattacharya, R. & Flora, S. J. S. Cyanide toxicity and its treatment. In: Handbook of Toxicology of Chemical Warfare Agents 255–270 https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-374484-5.00019-5 (Elsevier, 2009).

Dash, R. R., Gaur, A. & Balomajumder, C. Cyanide in industrial wastewaters and its removal: a review on biotreatment. J. Hazard Mater. 163, 1–11 (2009).

Hou, D. et al. Decomposition of cyanide from gold leaching tailings by using sodium metabisulphite and hydrogen peroxide. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 5640963 (2020).

Young, C. & Jordan, T. Cyanide remediation: current and past technologies. In: 10th Annual Conference on Hazardous Waste Research 104–129 (1995).

Botz, M. M. Overview of cyanide treatment methods. Min. Environ. Manag. 28, 30 (2001).

Ware, G. W. Cyanide. In: Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology: Continuation of Residue Reviews, United States Environmental Protection Agency Office of Drinking Water Health Advisories (ed. Ware, G. W.) 53–64 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4684-7083-3_5 (Springer New York, New York, NY, 1989).

Wong-Chong, G., Dzombak, D. & Ghosh, R. Introduction. In: Cyanide in Water and Soil. Chemistry, Risk, and Managment 1–14 (CRC Press Taylor & Francis Group, Boca Raton, 2006).

Dzombak, D., Ghosh, R. & Young, T. Physical–Chemical Properties and Reactivity of Cyanide in Water and Soil. in Cyanide in Water and Soil. Chemistry, Risk, and Managment 57–92 (CRC Press Taylor & Francis Group, Boca Raton, 2006).

Mekuto, L., Ntwampe, S. K. O. & Akcil, A. An integrated biological approach for treatment of cyanidation wastewater. Sci. Total Environ. 571, 711–720 (2016).

Kjeldsen, P. Behaviour of cyanides in soil and groundwater: a review. Water Air Soil Pollut. 115, 279–308 (1999).

Hanusa, T. P. Cyanide complexes of the transition metals. In: Encyclopedia of Inorganic Chemistry https://doi.org/10.1002/0470862106.ia059 (Wiley, 2005).

Chen, A. et al. Anaerobic cyanides oxidation with bimetallic modulation of biological toxicity and activity for nitrite reduction. J. Hazard Mater. 472, 134540 (2024).

Plumlee, G. S. et al. The environmental and medical geochemistry of potentially hazardous materials produced by disasters. In: Treatise on Geochemistry 257–304 https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-095975-7.00907-4 (Elsevier, 2014).

Jaszczak, E., Polkowska, Ż., Narkowicz, S. & Namieśnik, J. Cyanides in the environment—analysis—problems and challenges. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 24, 15929–15948 (2017).

Krasuska, U. et al. Hormetic action of cyanide: plant gasotransmitter and poison. Phytochem. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11101-023-09904-w (2023).

Anand, V. & Pandey, A. Role of microbes in biodegradation of cyanide and its metal complexes. In: Development in Wastewater Treatment Research and Processes, 205–224 https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-85839-7.00016-5 (Elsevier, 2022).

Sehrawat, A., Sindhu, S. S. & Glick, B. R. Hydrogen cyanide production by soil bacteria: biological control of pests and promotion of plant growth in sustainable agriculture. Pedosphere 32, 15–38 (2022).

Saeed, Q. et al. Rhizosphere bacteria in plant growth promotion, biocontrol, and bioremediation of contaminated sites: a comprehensive review of effects and mechanisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 10529 (2021).

Abd El-Rahman, A. F., Shaheen, H. A., Abd El-Aziz, R. M. & Ibrahim, D. S. S. Influence of hydrogen cyanide-producing rhizobacteria in controlling the crown gall and root-knot nematode, Meloidogyne incognita. Egypt J. Biol. Pest Control 29, 41 (2019).

Anand, A. et al. Contribution of hydrogen cyanide to the antagonistic activity of pseudomonas strains against phytophthora infestans. Microorganisms 8, 1144 (2020).

Ansari, M. W. et al. Cyanide produced with ethylene by ACS and its incomplete detoxification by β-CAS in mango inflorescence leads to malformation. Sci. Rep. 9, 18361 (2019).

Pattyn, J., Vaughan‐Hirsch, J. & Van de Poel, B. The regulation of ethylene biosynthesis: a complex multilevel control circuitry. New Phytol. 229, 770–782 (2021).

Crews, C. & Clarke, D. Natural toxicants: naturally occurring toxins of plant origin. In: Encyclopedia of Food Safety 261–268, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-378612-8.00173-6 (Elsevier, 2014).

Ram, S., Narwal, S., Gupta, O. P., Pandey, V. & Singh, G. P. Anti-nutritional factors and bioavailability: approaches, challenges, and opportunities. In: Wheat and Barley Grain Biofortification 101–128, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-818444-8.00004-3 (Elsevier, 2020).

Selmar, D. Biosynthesis of cyanogenic glycosides, glucosinolates and non-protein amino acids. In: Biochemistry of Plant Secondary Metabolism (ed. Wink, M.) 92–181 https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444320503.ch3 (Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford, UK, 2010).

Mudder, T. I. & Botz, M. M. Cyanide and society: a critical review. Eur. J. Miner. Process. Environ. Prot. 4, 62–74 (2004).

Kuyucak, N. & Akcil, A. Cyanide and removal options from effluents in gold mining and metallurgical processes. Min. Eng. 50–51, 13–29 (2013).

Chen, X. et al. A review of environmental functional materials for cyanide removal by adsorption and catalysis. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 157, 111298 (2023).

Jumbo, P. X. & Nieto, D. A. Tratamiento químico y biológico de efluentes mineros cianurados a escala laboratorio. Maskana 5, 133–139 (2016).

Rai, P., Mehrotra, S., Raj, A. & Sharma, S. K. A rapid and sensitive colorimetric method for the detection of cyanide ions in aqueous samples. Environ. Technol. Innov. 24, 101973 (2021).

Bhattacharya, R. Cyanides. In: Encyclopedia of the Neurological Sciences 919–920 https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-385157-4.00257-8 (2014).

Phuong, N. T. T. et al. Ultrasensitive monitoring of cyanide concentrations in water using a aucore –agshell hybrid-coating-based fiber optical sensor. Langmuir 39, 15799–15807 (2023).

Thabet, F. Smoke inhalation in children: focus on management. J. Clin. Images Med. Case Rep. 4, 2395 (2023).

Siegień, I. & Bogatek, R. Cyanide action in plants - from toxic to regulatory. Acta Physiol. Plant 28, 483–497 (2006).

Herfurth, A. M., Van Ohlen, M. & Wittstock, U. β-cyanoalanine synthases and their possible role in pierid host plant adaptation. Insects 8, 62 (2017).

Machingura, M., Salomon, E., Jez, J. M. & Ebbs, S. D. The β-cyanoalanine synthase pathway: beyond cyanide detoxification. Plant Cell Environ. 39, 2329–2341 (2016).

Olaya‐Abril, A. et al. Bacterial tolerance and detoxification of cyanide, arsenic and heavy metals: holistic approaches applied to bioremediation of industrial complex wastes. Microb. Biotechnol. 17, e14399 (2024).

Kim, M., Jee, S.-C., Kim, S., Hwang, K.-H. & Sung, J.-S. Identification and characterization of mRNA biomarkers for sodium cyanide exposure. Toxics 9, 288 (2021).

Tiwari, D. et al. Ferrate(VI): a green chemical for the oxidation of cyanide in aqueous/waste solutions. J. Environ. Sci. Health 42, 803–810 (2007).

Khodadad, A., Teimoury, P., Abdolahi, M. & Samiee, A. Detoxification of cyanide in a gold processing plant tailings water using calcium and sodium hypochlorite. Mine Water Environ. 27, 52–55 (2008).

Mudder, T., Botz, M. & Smith, A. Environmental geochemistry and fate of cyanide. In: Chemistry and Treatment of Cyanidation Wastes, 73–84 (Mining Journal Books Ltd, London, 2001).

Dzombak, D., Ghosh, R. & Wong-Ching, G. Cyanide cycle in nature. In: Cyanide in Water and Soil. Chemistry, Risk and Managment, 225–235 (CRC Press Taylor & Francis Group, Boca Raton, 2006).

Williams, D. J. Placing soil covers on soft mine tailings. In: Ground Improvement Case Histories: Compaction, Grouting and Geosynthetics 51–81 https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-100698-6.00002-7 (2015).

Botz, M. M., Mudder, T. I. & Akcil, A. U. Cyanide treatment: physical, chemical, and biological processes. In: Gold Ore Processing, 619–645 https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-63658-4.00035-9 (Elsevier, Amsterdam, 2016).

Cicerone, R. J. & Zellner, R. The atmospheric chemistry of hydrogen cyanide (HCN). J. Geophys Res. Oceans 88, 10689–10696 (1983).

Bruno, A. G. et al. Atmospheric distribution of HCN from satellite observations and 3-D model simulations. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 23, 4849–4861 (2023).

Lary, D. Atmospheric pseudohalogen chemistry. Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss. 4, 5381–5405 (2004).

Rader, W. S., Solujić, L., Milosavljević, E. B., Hendrix, J. L. & Nelson, J. H. Sunlight-induced photochemistry of aqueous solutions of hexacyanoferrate(II) and -(III) Ions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 27, 1875–1879 (1993).

Kossoff, D. et al. Mine tailings dams: characteristics, failure, environmental impacts, and remediation. Appl. Geochem. 51, 229–245 (2014).

Shen, L., Luo, S., Zeng, X. & Wang, H. Review on anti-seepage technology development of tailings pond in China. Procedia Eng. 26, 1803–1809 (2011).

von der Heyden, C. J. & New, M. G. Groundwater pollution on the Zambian copperbelt: deciphering the source and the risk. Sci. Total Environ. 327, 17–30 (2004).

de Lima, R. E., de Lima Picanço, J., da Silva, A. F. & Acordes, F. A. An anthropogenic flow type gravitational mass movement: the Córrego do Feijão tailings dam disaster, Brumadinho, Brazil. Landslides 17, 2895–2906 (2020).

Acheampong, M. A., Pereira, J. P. C., Meulepas, R. J. W. & Lens, P. N. L. Biosorption of Cu(II) onto agricultural materials from tropical regions. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 86, 1184–1194 (2011).

FAO & UNEP. Spatial distribution of soil pollution in Latin America and the Caribbean. In: Global assessment of soil pollution: Report. https://doi.org/10.4060/cb4894en (Rome, 2021).

Vinueza, D. et al. Determining the microbial and chemical contamination in Ecuador’s main rivers. Sci. Rep. 11, 17640 (2021).

Rötting, T. et al. Case studies in Peru, Bolivia and Chile on catchment management and mining impacts in arid and semi-arid south america-results from the CAMINAR project. In: 10th International Mine Water Association Congress (Newcastle University, 2008).

Marshall, B. G., Veiga, M. M., da Silva, H. A. M. & Guimarães, J. R. D. Cyanide contamination of the puyango-tumbes river caused by artisanal gold mining in Portovelo-Zaruma, Ecuador. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 7, 303–310 (2020).

Fuentes, I., Márquez-Ferrando, R., Pleguezuelos, J. M., Sanpera, C. & Santos, X. Long-term trace element assessment after a mine spill: pollution persistence and bioaccumulation in the trophic web. Environ. Pollut. 267, 115406 (2020).

Kovac, C. Cyanide spill could have long term impact. BMJ 320, 1294 (2000).

Ritmejerytė, E., Miller, R. E., Bayly, M. J. & Boughton, B. A. Visualization of cyanogenic glycosides in floral tissues. Appl. Environ. Metabolomics: Community Insights and Guidance from the Field, 29–44 https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-816460-0.00004-6 (2022).

Boter, M. & Diaz, I. Cyanogenesis, a plant defence strategy against herbivores. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 6982 (2023).

Wink, M. Special nitrogen metabolism. Plant Biochem. 439–486 https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012214674-9/50013-8 (1997).

Fuller, W. H. Cyanides in the environment with particular attention to the soil. In: Proceedings of the Conference on Cyanide and the Environment 19–44 (1984).

Gensa, U. Review on cyanide poisoning in ruminants. J. Biol. Agric. Healthc. 9, 12 (2019).

Giantin, S. et al. Overview of cyanide poisoning in cattle from sorghum halepense and S. bicolor cultivars in Northwest Italy. Animals 14, 743 (2024).

Kennedy, A., Brennan, A., Mannion, C. & Sheehan, M. Suspected cyanide toxicity in cattle associated with ingestion of laurel - a case report. Ir. Vet. J. 74, 2 (2021).

Razanamahandry, L. C., Karoui, H., Andrianisa, H. A. & Yacouba, H. Bioremediation of soil and water polluted by cyanide: a review. Afr. J. Environ. Sci. Tech. 11, 272–291 (2017).

United States Environmental Protection Agency. Cyanide clarification of free and total cyanide analysis for safe drinking water act. 1, 11–13 https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2016-08/documents/cyanide-clarification-free-and-total-cyanide-analysis-safe-drinking-water.pdf (2020).

United States Federal Government. Water quality guidance for the great lakes system, Part 131, Title 40. In: United States Code of Federal Regulations 24, 10 (2021).

Zhao, D., Lun, W. & Wei, J. Discussion on wastewater treatment process of coal chemical industry. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 100, 012067 (2017).

Prather, B. & Berkemeyer, R. Cyanide sources in petroleum refineries. In: Proceedings, 30th Purdue Industrial Waste Conference, West Lafayette, IN (1975).

Wong-Chong, G., Ghosh, R. & Dzombak, D. Cyanide treatment technology: overview. In: Cyanide in Water and Soil. Chemistry, Risk and Managment 387–391 (CRC Press Taylor & Francis Group, Boca Raton, 2006).

Chen, A. et al. Catalytic oxidation of biorefractory cyanide-containing coking wastewater by deconjugation effect of bimetal copper-loaded activated carbon. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 11, 111283 (2023).

Mosher, J. B. & Figueroa, L. Biological oxidation of cyanide: a viable treatment option for the minerals processing industry? Min. Eng. 9, 573–581 (1996).

Akcil, A. Destruction of cyanide in gold mill effluents: biological versus chemical treatments. Biotechnol. Adv. 21, 501–511 (2003).

Société Générale de Surveillance. Cyanide destruction. SGS Mineral services—T3 SGS 018 1–3 https://www.sgs.com/pt/-/media/sgscorp/documents/corporate/brochures/sgs-min-wa017-cyanide-destruction-en-11.cdn.pt.pdf (2005).

Vafaie, H. & Seyyed Alizadeh Ganji, S. M. Modeling, optimizing, and characterizing elimination process of cyanide ion from an industrial wastewater of gold mine by Caro’s acid method. J. Min. Environ. 13, 839–849 (2022).

Teixeira, L. A. C., Andia, J. P. M., Yokoyama, L., da Fonseca Araújo, F. V. & Sarmiento, C. M. Oxidation of cyanide in effluents by Caro’s acid. Min. Eng. 45, 81–87 (2013).

Malmir, N., Fard, N. A., Aminzadeh, S., Moghaddassi-Jahromi, Z. & Mekuto, L. An overview of emerging cyanide bioremediation. Methods Process. 10, 1724 (2022).

Wei, C., Zhang, F., Hu, Y., Feng, C. & Wu, H. Ozonation in water treatment: the generation, basic properties of ozone and its practical application. Rev. Chem. Eng. 33, 49–89 (2017).

Hoigné, J. & Bader, H. The role of hydroxyl radical reactions in ozonation processes in aqueous solutions. Water Res. 10, 377–386 (1976).

Abdulla, A. K. et al. Removal of cyanide from wastewater using iron electrodes. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 1088, 012002 (2022).

Eke-emezie, N., Etuk, B. R., Akpan, O. P. & Chinweoke, O. C. Cyanide removal from cassava wastewater onto H3PO4 activated periwinkle shell carbon. Appl. Water. Sci. 12, 157 (2022).

Zhou, S., Li, W., Liu, W. & Zhai, J. Removal of metal ions from cyanide gold extraction wastewater by alkaline ion-exchange fibers. Hydrometallurgy 215, 105992 (2023).

Jaramillo-Fierro, X. & León, R. Effect of doping TiO2 NPs with lanthanides (La, Ce and Eu) on the adsorption and photodegradation of cyanide—a comparative study. Nanomaterials 13, 1068 (2023).

Atkins, P. & De Paula, J. An introduction to solid surfaces. In: Physical Chemistry: Thermodynamics, Structure, and Change, 938–939 (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2014).

Ho, S. Low-cost adsorbents for the removal of phenol/phenolics, pesticides, and dyes from wastewater systems: a review. Water 14, 3203 (2022).

Dhongade, S., Meher, A. K. & Mahapatra, S. Removal of free cyanide (CN−) from water and wastewater using activated carbon: a review, 355–379 https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-1847-6_15 (2022).

Eskandari, P., Farhadian, M., Solaimany Nazar, A. R. & Goshadrou, A. Cyanide adsorption on activated carbon impregnated with ZnO, Fe2O3, TiO2 nanometal oxides: a comparative study. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 18, 297–316 (2021).

Chao-Hai, W. & Xu-Liang, C. Adsorption and catalytic processes of cyanide solutions and acid-washed activated carbon. Carbon 31, 1319–1324 (1993).

Stavropoulos, G. G., Skodras, G. S. & Papadimitriou, K. G. Effect of solution chemistry on cyanide adsorption in activated carbon. Appl. Therm. Eng. 74, 182–185 (2015).

Pathak, U. et al. Evaluation of mass transfer effect and response surface optimization for abatement of phenol and cyanide using immobilized carbon alginate beads in a fixed bio‐column reactor. Asia-Pac. J. Chem. Eng. 15, e2405 (2020).

Noroozi, R., Al-Musawi, T. J., Kazemian, H., Kalhori, E. M. & Zarrabi, M. Removal of cyanide using surface-modified Linde Type-A zeolite nanoparticles as an efficient and eco-friendly material. J. Water Process Eng. 21, 44–51 (2018).

Maulana, I. & Takahashi, F. Cyanide removal study by raw and iron-modified synthetic zeolites in batch adsorption experiments. J. Water Process Eng. 22, 80–86 (2018).

Jaramillo-Fierro, X., Alvarado, H., Montesdeoca, F. & Valarezo, E. Faujasite-type zeolite obtained from ecuadorian clay as a support of ZnTiO3/TiO2 NPs for cyanide removal in aqueous solutions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 9281 (2023).

Samiee Beyragh, A., Varsei, M., Meshkini, M., Khodadadi Darban, A. & Gholami, E. Kinetics and adsorption isotherms study of cyanide removal from gold processing wastewater using natural and impregnated zeolites. Iran. J. Chem. Chem. Eng. 37, 139–149 (2018).

Aliprandini, P. et al. Evaluation of biosorbents as an alternative for mercury cyanide removal from aqueous solution. Min. Eng. 204, 108431 (2023).

Chong, Z. T., Soh, L. S. & Yong, W. F. Valorization of agriculture wastes as biosorbents for adsorption of emerging pollutants: Modification, remediation and industry application. Results Eng. 17, 100960 (2023).

Karim, A., Raji, Z., Karam, A. & Khalloufi, S. Valorization of fibrous plant-based food waste as biosorbents for remediation of heavy metals from wastewater—a review. Molecules 28, 4205 (2023).

Sánchez-Ponce, L. et al. Potential use of low-cost agri-food waste as biosorbents for the removal of Cd(II), Co(II), Ni(II) and Pb(II) from aqueous solutions. Separations 9, 309 (2022).

Ahmad, F. & Zaidi, S. Potential use of agro/food wastes as biosorbents in the removal of heavy metals. In: Emerging Contaminants. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.94175 (2021).

Valiuniene, A., Baltrunas, G., Keršulyte, V., Margarian, Ž. & Valinčius, G. The degradation of cyanide by anodic electrooxidation using different anode materials. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 91, 269–274 (2013).

Abdel-Aziz, M. H. et al. Removal of cyanide from liquid waste by electrochemical oxidation in a new cell design employing a graphite anode. Chem. Eng. Commun. 203, 1045–1052 (2016).

Chaplin, B. P. Advantages, disadvantages, and future challenges of the use of electrochemical technologies for water and wastewater treatment. In: Electrochemical Water and Wastewater Treatment 451–494, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-813160-2.00017-1 (Elsevier, 2018).

Xu, H., Li, A., Feng, L., Cheng, X. & Ding, S. Destruction of cyanide in aqueous solution by electrochemical oxidation method. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 7, 7516–7525 (2012).

Faria, L. U. S., Oliveira, K. S. G. C., Veroli, A. B., Aquino, J. M. & Ruotolo, L. A. M. Energy consumption and reaction rate optimization combining turbulence promoter and current modulation for electrochemical mineralization. Chem. Eng. J. 418, 129363 (2021).

Güven, G., Perendeci, A., Özdemir, K. & Tanyolaç, A. Specific energy consumption in electrochemical treatment of food industry wastewaters. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 87, 513–522 (2012).

Öğütveren, Ü. B., Törü, E. & Koparal, S. Removal of cyanide by anodic oxidation for wastewater treatment. Water Res. 33, 1851–1856 (1999).

Berenguer, R., Quijada, C., La Rosa-Toro, A. & Morallón, E. Electro-oxidation of cyanide on active and non-active anodes: Designing the electrocatalytic response of cobalt spinels. Sep Purif. Technol. 208, 42–50 (2019).

Felix-Navarro, R. M., Lin, S. W., Violante-Delgadillo, V., Zizumbo-Lopez, A. & Perez-Sicairos, S. Cyanide degradation by direct and indirect electrochemical oxidation in electro-active support electrolyte aqueous solutions. Chem. Soc. 55, 51–56 (2011).

Kim, T., Kim, T.-K. & Zoh, K.-D. Removal mechanism of heavy metal (Cu, Ni, Zn, and Cr) in the presence of cyanide during electrocoagulation using Fe and Al electrodes. J. Water Process Eng. 33, 101109 (2020).

Tian, L. et al. Overcoming electrostatic interaction via strong complexation for highly selective reduction of CN− into N2. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 61, e202214145 (2022).

Barrera-Díaz, C. et al. Electrochemical advanced oxidation processes: an overview of the current applications to actual industrial effluents. J. Mex. Chem. Soc. 58, 256–275 (2014).

Deng, Y. & Zhao, R. Advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) in wastewater treatment. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40726-015-0015-z (2015).

Kamath, D., Mezyk, S. P. & Minakata, D. Elucidating the elementary reaction pathways and kinetics of hydroxyl radical-induced acetone degradation in aqueous phase advanced oxidation processes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 7763–7774 (2018).

Ganiyu, S. O., Martínez-Huitle, C. A. & Oturan, M. A. Electrochemical advanced oxidation processes for wastewater treatment: Advances in formation and detection of reactive species and mechanisms. Curr. Opin. Electrochem. 27, 100678 (2021).

Moreira, F. C., Boaventura, R. A. R., Brillas, E. & Vilar, V. J. P. Electrochemical advanced oxidation processes: a review on their application to synthetic and real wastewaters. Appl Catal. B 202, 217–261 (2017).

Tian, L. et al. Mineralization of cyanides via a novel Electro-Fenton system generating •OH and •O2−. Water Res. 209, 117890 (2022).

Ibrahim, N., Zainal, S. F. F. S. & Aziz, H. A. Application of UV-based advanced oxidation processes in water and wastewater treatment, 384–414 https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-5766-1.ch014 (2019).

Amaro-Medina, B. M. et al. Efficiency of adsorption and photodegradation of composite TiO2/Fe2O3 and industrial wastes in cyanide removal. Water (Basel) 14, 3502 (2022).

Sarla, M., Pandit, M., Tyagi, D. K. & Kapoor, J. C. Oxidation of cyanide in aqueous solution by chemical and photochemical process. J. Hazard Mater. 116, 49–56 (2004).

Chiang, K., Amal, R. & Tran, T. Photocatalytic oxidation of cyanide: kinetic and mechanistic studies. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 193, 285–297 (2003).

Akcil, A., Karahan, A. G., Ciftci, H. & Sagdic, O. Biological treatment of cyanide by natural isolated bacteria (Pseudomonas sp.). Min. Eng. 16, 643–649 (2003).

Srivastava, A. C. & Duvvuru Muni, R. R. Phytoremediation of cyanide. In: Plant Adaptation and Phytoremediation 399–426, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-9370-7_18 (Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, 2010).

Maharana, J., Pandey, S. & Dhal, N. K. A brief overview of the degradation of cyanides and phenols in the environment with reference to the coke oven industry discharge. Geomicrobiology 39, 619–630 https://doi.org/10.1080/01490451.2022.2045648 (2022).

Dell’ Anno, F. et al. Bacteria, fungi and microalgae for the bioremediation of marine sediments contaminated by petroleum hydrocarbons in the omics era. Microorganisms 9, 1695 (2021).

Ebbs, S. Biological degradation of cyanide compounds. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 15, 231–236 (2004).

Luque-Almagro, V. M. et al. Exploring anaerobic environments for cyanide and cyano-derivatives microbial degradation. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 102, 1067 (2018).

Alvillo-Rivera, A., Garrido-Hoyos, S., Buitrón, G., Thangarasu-Sarasvathi, P. & Rosano-Ortega, G. Biological treatment for the degradation of cyanide: a review. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 12, 1418–1433 (2021).

Chen, A. et al. Function and direction of cyanide in coking wastewater: from water treatment to environmental migration. ACS EST Water 3, 3980–3991 (2023).

Roldán, M. et al. Bioremediation of cyanide-containing wastes. EMBO Rep. 22, e53720 (2021).

Dwivedi, N., Balomajumder, C. & Mondal, P. Applications of microorganisms in biodegradation of cyanide from wastewater. In: Advances in Microbial Biotechnology 301–328 https://doi.org/10.1201/9781351248914-12 (2019).

de Oliveira Schmidt, V. K. et al. Cassava wastewater valorization for the production of biosurfactants: surfactin, rhamnolipids, and mannosileritritol lipids. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 39, 65 (2023).

Cruz, I. A. et al. Valorization of cassava residues for biogas production in Brazil based on the circular economy: an updated and comprehensive review. Clean. Eng. Technol. 4, 100196 (2021).

Fleming, C. A. Chapter 36 - cyanide recovery. In: Gold Ore Processing (Second Edition) (ed. Adams, M. D.) 647–661, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-63658-4.00036-0 (Elsevier, 2016).

Zheng, Y., Li, Z., Wang, X., Gao, X. & Gao, C. The treatment of cyanide from gold mine effluent by a novel five-compartment electrodialysis. Electrochim. Acta 169, 150–158 (2015).

Kyoseva, V., Todorova, E. & Dombalov, I. Comparative assessment of the methods for destruction of cyanides used in gold mining industry. J. Univ. Chem. Technol. Metall. 44, 403–408 (2009).

Huda, M. F. & Helmy, Q. Removal of cyanide from alumina smelter wastewater using precipitation and filtration technique. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 896, 012075 (2021).

Morillo Esparza, J. et al. Combined treatment using ozone for cyanide removal from wastewater: a comparison. Rev. Int. Contam. Ambient. 35, 459–467 (2019).

Amaouche, H. et al. Removal of cyanide in aqueous solution by oxidation with hydrogen peroxide catalyzed by copper oxide. Water Sci. Technol. 80, 126–133 (2019).

Kim, T. K. et al. Degradation mechanism of cyanide in water using a UV-LED/H2O2/Cu2+ system. Chemosphere 208, 441–449 (2018).

Martin, N., Ya, V., Naddeo, V., Choo, K. H. & Li, C. W. Cyanide removal and recovery by electrochemical crystallization process. Water 13, 2704 (2021).

Das, P. P. et al. Integrated ozonation assisted electrocoagulation process for the removal of cyanide from steel industry wastewater. Chemosphere 263, 128370 (2021).

Yang, W. et al. Persulfate enhanced electrochemical oxidation of highly toxic cyanide-containing organic wastewater using boron-doped diamond anode. Chemosphere 252, 126499 (2020).

Chen, Y., Song, Y., Wu, L. & Dong, P. Role of hypochlorite in the harmless treatment of cyanide tailings through slurry electrolysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 29, 40178–40189 (2022).

Jauto, A. H., Memon, S. A., Channa, A. & Khoja, A. H. Efficient removal of cyanide from industrial effluent using acid treated modified surface activated carbon. Energy Sources 41, 2715–2724 (2019).

Tu, Y. et al. Removal of cyanide adsorbed on pyrite by H2O2 oxidation under alkaline conditions. J. Environ. Sci. 78, 287–292 (2019).

Razanamahandry, L. C. et al. Removal of free cyanide by a green photocatalyst ZnO nanoparticle synthesized via eucalyptus globulus leaves. In: Photocatalysts in Advanced Oxidation Processes for Wastewater Treatment 271–288 https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119631422.CH9 (2020).

Pérez-Cid, B., Calvar, S., Moldes, A. B. & Manuel Cruz, J. Effective removal of cyanide and heavy metals from an industrial electroplating stream using calcium alginate hydrogels. Molecules 25, 5183 (2020).

Mondal, M., Mukherjee, R., Sinha, A., Sarkar, S. & De, S. Removal of cyanide from steel plant effluent using coke breeze, a waste product of steel industry. J. Water Process Eng. 28, 135–143 (2019).

Behnamfard, A., Chegni, K., Alaei, R. & Veglio, F. The effect of thermal and acid treatment of kaolin on its ability for cyanide removal from aqueous solutions. Environ. Earth Sci. 78, 1–12 (2019).

Manyuchi, M. M., Sukdeo, N. & Stinner, W. Potential to remove heavy metals and cyanide from gold mining wastewater using biochar. Phys. Chem. Earth 126, 103110 (2022).

Ibrahem, M. & Al-Ubaidy, B. Evaluation of parameters affecting the rice husks performance on cyanide ion removal from wastewater. Wasit J. Eng. Sci. 6, 66–74 (2018).

Bahrami, A. et al. Isolation and removal of cyanide from tailing dams in gold processing plant using natural bitumen. J. Environ. Manag. 262, 110286 (2020).

Moussavi, G. & Khosravi, R. Removal of cyanide from wastewater by adsorption onto pistachio hull wastes: Parametric experiments, kinetics and equilibrium analysis. J. Hazard Mater. 183, 724–730 (2010).

Alalwan, H. A., Abbas, M. N. & Alminshid, A. H. Uptake of cyanide compounds from aqueous solutions by lemon peel with utilising the residue absorbent as rodenticide. Indian Chem. Eng. 62, 40–51 (2019).

Singh, N. & Balomajumder, C. Phytoremediation potential of water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes) for phenol and cyanide elimination from synthetic/simulated wastewater. Appl. Water Sci. 11, 144 (2021).

Sampanpanish, P. Arsenic, manganese, and cyanide removal in a tailing storage facility for a gold mine using phytoremediation. Remediation J. 28, 83–89 (2018).

Jiang, W. et al. Biodegradation of cyanide by a new isolated Aerococcus viridans and optimization of degradation conditions by response surface methodology. Sustainability 14, 15560 (2022).

Maiga, Y. et al. Isolation and assessment of cyanide biodegradation potential of indigenous bacteria from contaminated. Soil. J. Environ. Prot. 13, 716–731 (2022).

Javaheri Safa, Z. et al. Biodegradation of cyanide to ammonia and carbon dioxide by an industrially valuable enzyme from the newly isolated Enterobacter zs 56, 1131–1137. https://doi.org/10.1080/10934529.2021.1967653 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador for funding the Open Access payment.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceived the project, K.V.-E. and P.J.E.-M.; visualization, K.V.-E. and P.J.E.-M.; supervision, K.V.-E. and P.J.E.-M.; investigation, D.A.-A., K.V.-E., and P.J.E.-M.; writing—original draft preparation, D.A.-A., K.V.-E., and P.J.E.-M.; writing—review and editing, D.A.-A., K.V.-E., and P.J.E.-M.; project administration, P.J.E.-M.; funding acquisition, P.J.E.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vaca-Escobar, K., Arregui-Almeida, D. & Espinoza-Montero, P. Chemical, ecotoxicological characteristics, environmental fate, and treatment methods applied to cyanide-containing wastewater. npj Clean Water 7, 103 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41545-024-00392-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41545-024-00392-9

This article is cited by

-

Influence of Hydrogen Peroxide and Sodium Acetate on Gold Cyanidation: Laboratory and Pilot-Scale Tests

Mining, Metallurgy & Exploration (2026)

-

A simple alternative method for estimating hemoglobin

Applied Physics A (2025)

-

Solvatochromism of an ICT-based Colourimetric Probe and its Utility to Sense Cyanide in Aqueous Solution and to Estimate it in Food Materials

Journal of Fluorescence (2025)

-

Optimizing Biogenic Cyanide Production Using Indigenous Cyanogenic Microorganisms for Bioleaching of Precious Metals

Journal of Sustainable Metallurgy (2025)

-

Towards healthy and economically sustainable communities through clean water and resource recovery

npj Clean Water (2024)