Abstract

Solving three-dimensional (3D) multi-physics forward and inverse problems is indispensable for fundamental understanding and optimal design of membrane-based desalination systems. Unfortunately, it is computationally expensive when applying traditional numerical methods. Herein, a modified Fourier neural operator (FNO)-based method is proposed to efficiently solve complex 3D multi-physics problems. The intelligent solver solves the 3D forward problems in seconds, which is approximately 105-106 times faster than traditional finite-element based method with a comparable solution quality. The average prediction accuracy is more than 96%. Moreover, the proposed FNO-based method is mesh-independent and has zero-shot super-resolution ability. It can be used to provide a fast solution for the optimal design of membrane module to mitigate concentration polarization and membrane fouling for next-generation ultrapermeable membrane system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

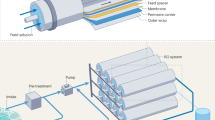

Simulation of complex physical systems described by partial differential equations (PDEs) has important applications1 in multiple fields, such as chemical engineering2, aerospace engineering3 and climate prediction4. Nowadays, the shortage of fresh water is a growing problem, which is further exacerbated by population growth and economic development. Desalination is an effective way to increase local fresh water supplies5. Membrane-based separation technologies, such as, reverse osmosis (RO) have been widely applied for seawater and brackish water desalination6. In recent years, ultrapermeable membranes (UPMs) based on carbon-nanotubes7, graphene8, aquaporins9, conjugated-polymer10, fluorous oligoamide nanochannel11 and enhanced polyamide12, have attracted widespread attention due to their significant potential on enhancing water production efficacy. However, there are still some difficulties in the large-scale production of UPMs. And although UPMs have many advantages, the intensified concentration polarization (CP) and membrane fouling make them impractical to operate at a high water flux, due to the performance limitations of current membrane module on fluid mechanics and transport13. In addition, UPMs have a limiting flux, which is influenced by the mass transfer coefficient14. Therefore, the advantage of UPMs may not be as significant as originally envisioned in practice15 and UPMs may make less impact on process efficiency than the redesign of membrane module in industrial applications16. Because the redesign of membrane module could improve mass transfer coefficient and reduce pressure drop, it is crucial for maximizing the returns of UPM systems17. Optimal design of membrane module involves solving numerous three-dimensional (3D) multi-physics models in feed spacer-filled channels, which is computationally expensive using traditional numerical methods. Therefore, to address the complicated nonlinear channel flow and mass transport in RO, the development of an efficient computational approach is of great significance.

The models used to describe the complicated 3D multi-physics problems are mainly divided into two types: phenomenological models and mechanistic models18. The separation performance of the membranes is represented by measurable parameters in phenomenological models, which regard the membranes as “black boxes”. While these models can effectively characterize performance, they do not offer a mechanistic explanation. In contrast, mechanistic models facilitate a more fundamental understanding of membranes transport by connecting the separation performance observed in the membranes to their physical and chemical properties as well as those of the solute materials. However, it is difficult to build an exact mechanistic model for a complex process. Traditional computational methods, such as computational fluid dynamics (CFD), describe the multi-physics problems using many nonlinear PDEs and then apply numerical algorithms to solve the problems in discrete meshes. For these type of problems, numerical methods, including finite difference method (FDM)19, finite volume method (FVM)20 and finite element method (FEM)21, are generally computationally expensive22. In comparison, particle methods, such as Lattice Boltzmann method (LBM)23 and smoothed particle hydrodynamics (SPH)24, are advantageous in solving the multi-physics problems with complex structures. However, their computational cost increases with the complexity of the computational domains25. Advances in computing power and the advent of supercomputers have accelerated the calculation. Nevertheless, the precise 3D simulation of RO using these traditional methods is still a daunting task, due to the complex 3D structures and nonlinear items in PDEs.

Deep learning methods have been proven to have universal nonlinear fitting ability and can approximate the governing equations of complex systems26. There are three main types of deep learning methods used to solve PDEs27, finite-dimensional operators, neural-FEM and neural operators. Finite-dimensional operators use deep convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to approximate the solution operator in finite-dimensional Euclidean space25,28,29, and are widely used in fluid flow problems. However, these methods are mesh-dependent and are limited by the size of discretization and geometry of the training data27. Neural-FEM methods, such as physics-informed neural network30, deep Galerkin method26 and deep Ritz method31, directly parameterize the solution function as a neural network. Because the networks are constructed based on mathematical knowledge, they are interpretable. However, Neural-FEM methods are designed to model one specific instance of PDE, and they are computationally expensive to train new neural networks when the parameters of PDE change. Neural operators learn PDE operators, such as DeepONet32 and Fourier neural operator (FNO)27, which are mesh-independent and only need to be trained once even when the parameters of the PDE change. However, the lack of interpretability and difficulty in assessing model generalization limit their application to practical engineering problems.

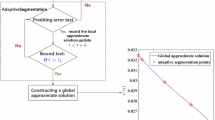

FNO constructs mappings between function spaces by parameterizing an integral kernel in Fourier space and shows a strong ability to solve parametric PDEs. The zero-shot super-resolution of FNO allows a higher resolution prediction when trained with lower resolution data. This feature is important for physical problems which need direct numerical simulation at a small scale1. However, FNO can only handle regular and fixed size data, while the computational results of complex physical problems are usually unstructured and the sizes of computational domains are unfixed. In order to tackle such problems, fully convolutional neural network (FCNN) replaces fully connected layers with convolutional layers33, while spatial pyramid pooling (SPP) could generate a fixed-length representation regardless of the input size of data34, but SPP is not suitable for engineering problems where the size of the computational domains needs to be maintained. Recurrent neural network35 and transformer model36 could tackle sequences of different lengths, and are applied to solve 2D and 3D problems37,38. However, due to the strong spatial correlation between data points in this problem, converting 3D data into 1D sequence degrades prediction performance, even with positional embedding and attention modules. Moreover, acquiring large datasets to meet training requirements for engineering problems remains challenging. Therefore, in this work, the idea of FCNN33 is borrowed to modify the framework of FNO. The accuracy of the modified FNO-based method is evaluated by the high-fidelity CFD simulation data computed by large-scale high-throughput computation using supercomputing39.

Results

3D multi-physical simulations with modified FNO-based method

The 3D multi-physics problems considered in this work are solved on the complex structures via a new deep learning method, which is shown in Fig. 1. High-fidelity CFD data are obtained by solving forward problems on the “Tianhe-2” supercomputer using a high-throughput strategy. In our previous study40 on brackish water RO desalination, a hybrid model was established in coupling a 3D CFD model with a one-dimensional (1D) system-level model. Computing by the hybrid model, the calculated transmembrane pressure had less than 5% deviation and the total flow rate was almost identical with industrial data41. The industrial data were obtained from an industrial RO train in Chino Desalter I located in Chino, California. The CFD models we use in this work apply the same modeling techniques and governing equations as those used in our previous work40, the only difference between them is we modify initial and boundary conditions to adapt different processes. These 3D CFD models are discretized by unstructured meshes, which cannot be handled by FNO directly. Although the body-fitted curvilinear interpolation method can render more details42, it is challenging for complex geometries. To this end, linear interpolation is applied to convert the unstructured data to regularly organized data. To reflect the data variation in a small range, logarithmic intervals are used for interpolation in the concentration problem, and two separate networks are used for fluid flow and mass transfer. In addition, in order to deal with different sizes of input data, the fully connected layers in the original framework of FNO27 are replaced by convolution layers whose convolution kernel is 1 × 1 × 1. As shown in Fig. 1, the framework of the modified FNO-based method includes both convolution layers and Fourier layers: the convolution layers map the input spaces to high-dimensional spaces and reduce the dimensionality to that required for the output function spaces, while the Fourier layers extract information.

The methodology involves training deep neural networks to take inlet velocity, geometry, initial concentration and coordinates of each model as input, and then producing the distribution of velocity, pressure and concentration as output. 960 CFD models with \(1.5\times {10}^{6}-7.6\times {10}^{6}\) unstructured data points are interpolated into \(2.3\times {10}^{4}-5.9\times {10}^{5}\) organized points to train and evaluate the modified FNO-based method, where 582 models are training data, 194 models are validation data and 184 models are testing data. The deep networks are trained for 500 epochs, and each network takes ~5.5 h on the computer configured with Intel(R) Xeon(R) CPU E5-2640 v4 and NVIDIA GeForce RTX 2080 Ti GPU.

The CPU time required for each CFD model simulation ranges from 0.6 to 12.9 h using 4 computational nodes on the “Tianhe-2” supercomputer. And the average time of each model predicted by the modified FNO-based method is 0.04 s using a single computer. Therefore, the modified FNO-based method is approximately \({10}^{5}-{10}^{6}\) times faster without losing accuracy. In addition, our strategy proposed in this work requires 7 times less training time than the multilayer perceptron (MLP)43 which needs 40 h training time using Intel Xeon Gold 6130 CPU and NVIDIA Tesla V100-SXM2 GPU, whereas offering better precision for the same type of problems.

Evaluation of the predictions with the modified FNO-based method

Structure similarity index measure (SSIM)44, root mean squared error (RMSE) and coefficient of determination (\({R}^{2}\)) are used to evaluate the difference between the predicted results of the modified FNO-based method and computational results of CFD. RMSE and \({R}^{2}\) focus on the point-to-point difference, while SSIM is a perceptual model that pays more attention to the visual difference of human eyes.

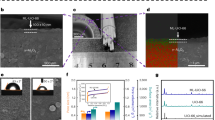

In order to eliminate the impact of the order of magnitude on the evaluation, the data for comparison are normalized to [0, 1] according to the maximum and minimum values of the CFD results. The evaluation of SSIM is the mean value of three cross sections at \(\frac{1}{4}{L}_{x},\frac{2}{4}{L}_{x},\frac{3}{4}{L}_{x}\), respectively. The comparisons between CFD simulation and FNO prediction are summarized in Supplementary Tables S1, S2 and Fig. 2. Compared with CFD, the average accuracy of the modified FNO-based method evaluated by SSIM, RMSE and \({R}^{2}\) is greater than 0.990, 0.970 and 0.961 in velocity, greater than 0.994, 0.967 and 0.977 in pressure, and greater than 0.989, 0.995 and 0.995 in concentration, respectively. The accuracy of MLP43, evaluated by RMSE, is 0.935, 0.983 and 0.951 for velocity, pressure and concentration, respectively. Thus, the modified FNO-based method offers better precision. According to Fig. 2, 99% of models have errors between 0.95 and 1 in SSIM. For RMSE, 83% and 17% of models fall in the ranges of 0.95–1 and 0.9–0.95 respectively. And for R2, 86% and 11% of models fall in the ranges of 0.95–1 and 0.9–0.95 respectively. However, there are a few models that deviate slightly. The main reason is that these models are constructed with unrealistic design parameters for the feed spacer, whose calculated velocity, pressure and concentration fields have greatly deviation than the others. Another reason is that pressure is trained with velocity in this work. However, their values differ by three orders of magnitude.

The three components of velocity calculated by CFD and predicted by the modified FNO-based method are shown in Supplementary videos 1–3 in the supplementary materials. And the results of 3 geometries of typical feed spacers are shown in Figs. 3–5 as examples. According to the results shown in the figures, the modified FNO-based method can well predict the three components of velocity, and the existence of high velocity zones. Some differences with the CFD results are still noted, which may be due to the loss of details caused by the selection of Fourier modes.

The pressure calculated by CFD and predicted by the modified FNO-based method are shown in Supplementary video 4 in the supplementary materials. And the results of 3 geometries of typical feed spacers are shown in Fig. 6 as examples. The local pressure distribution along the transversal line of the membrane surface at \(z=0.5H,y=0.25{L}_{y},0\le x\le {L}_{x}\) is shown in Supplementary Fig. S1. According to the results shown in Fig. 6 and Supplementary Fig. S1, the modified FNO-based method accurately predicts the pressure distribution.

The concentration calculated by CFD and predicted by the modified FNO-based method are shown in supplementary video 5 in the supplementary materials. And the results of 3 geometries of typical feed spacers are shown in Fig. 7 as examples. According to the results shown in the figure, the modified FNO-based method can predict the CP phenomenon, but there are some differences with the shape of the boundary layer calculated by the CFD model. This may be caused by the loss of data when interpolating the unstructured mesh into the structured mesh, or the limited capability of the data-driven training method to learn abrupt changes at the boundary. The CP factor45, \({\rm{CPF}}={{\rm{e}}}^{{J}_{{\rm{w}}}/k}\), is influenced by the permeation flux (\({J}_{{\rm{w}}}\)) and the mass transfer coefficient (\(k\)). Therefore, if \({J}_{{\rm{w}}}\) is enhanced, and \(k\) is maintained, the CP phenomenon will worsen. Improving the cross velocity (\(\bar{u}\)) could increase \(k\). The previous study45 indicated that doubling \(k\) using a commercial membrane module would lead to a 9-fold friction loss that must be overcome by the pump. Module design could enhance \(k\) with a moderate friction loss penalty, and thereby enable to improve \({J}_{{\rm{w}}}\). However, optimal design of membrane module requires to iteratively solve many high-fidelity multi-physics models, which is computationally intensive and time-consuming using CFD simulations. Herein, the computational time of the modified FNO-based method is approximately \({10}^{5}-{10}^{6}\) times faster than the CFD approach while both methods have an equivalent accuracy. It enables fast computation for complex geometries and therefore greatly reduces the computational time of optimal design of membrane modules.

Zero-shot super-resolution

The research of Li et al.27 shows that FNO is mesh-independent, and it can be trained on a low resolution dataset and evaluated on a higher resolution dataset without seeing any higher resolution data. This feature is called zero-shot super-resolution. In this work, we study on whether the modification changes this feature of FNO.

We double the amount of data in all three directions, i.e., we change the amount of data in the new dataset to \((2{N}_{{\rm{x}}})\times (2{N}_{{\rm{y}}})\times (2{N}_{{\rm{z}}})\), where \({N}_{{\rm{x}}},{N}_{{\rm{y}}},{N}_{{\rm{z}}}\) denote the amount of data of the original training dataset in the x, y and z directions respectively.

The comparison between the higher resolution dataset and the CFD data are shown in Supplementary Tables S3 and S4. Compared with Supplementary Tables S1 and S2, the accuracy of the modified FNO-based method in the higher resolution dataset is slightly lower than that in the original dataset for most models, whereas differentiable errors are noticed in some of the cases. This may be because the higher resolution data was not seen during the training. Another reason is that the truncated modes in the Fourier layers, which are utilized for extracting information, are selected by the smallest size in the original dataset. However, the difference between the sizes of different models is quite large, and the increase in the amount of data make the difference even larger. The small number of the truncated modes will result in the Fourier layers not being able to extract enough information for prediction46. The research of Qin et al. based on traditional FNO also shows the negative impact on the prediction when training on resolutions lower than testing data47.

The three components of velocity of the higher resolution dataset predicted by the modified FNO-based method are shown in Supplementary Fig. S2. By comparing with the computational results of CFD and the predicted results of original dataset, we could conclude that although the modified FNO-based method is trained on the lower resolution dataset, it can still predict the distribution of velocity well and the existence of the high velocity zones in the higher resolution dataset. However, as with the predicted result of the original dataset, there are still some numerical differences.

The pressure and concentration of the higher resolution dataset predicted by the modified FNO-based method are shown in Supplementary Fig. S3. Compared with the computational results of CFD and the predicted results of the original dataset, the modified FNO-based method can predict the distribution of pressure and the CP phenomenon in the higher resolution dataset well, but there are still some differences with the shape of the boundary layer calculated by CFD. This may be due to the loss of information in the original resolution dataset used in the training process, which has a negative effect on the prediction accuracy of the higher resolution dataset.

In summary, the modified FNO-based method proposed in this work is mesh-independent and has the feature of zero-shot super-resolution. In this work, we simplify the computational domain to contain only a few feed spacer cells. But there are more than 1 million feed spacer cells in a typical membrane module45. Because of the complex structures of feed spacers, the finer meshes are required to obtain high-fidelity results. Therefore, it is computationally expensive for the simplified computational domain and impractical for the whole systems using CFD approach. And a recalculation is required in order to obtain finer results. In contrast, zero-shot super-resolution allows the modified FNO-based method obtain finer results in very short time without retraining. Although full-size industrial membrane module simulations have not been validated, this feature offers opportunities for future research in this domain.

Discussion

Solving the multi-physics forward and inverse problems is very crucial for the optimal design of RO desalination processes. However, it is computationally expensive using established numerical methods. Aiming at developing a universal and efficient computational method for 3D multi-physics problems with different boundary conditions and sizes of computational domains, the modified FNO-based method is proposed. The solution quality and efficiency of the newly developed method have also been validated by tests with the high-fidelity CFD simulation data. The following conclusions are drawn:

-

(1)

The modified FNO-based method can tackle problems with different boundary conditions and computational domain sizes. Moreover, it can achieve a second-level calculation which is \(5\times {10}^{4}-{10}^{6}\) times increase in computational speed compared to FEM, while maintaining the solution quality.

-

(2)

The modified FNO-based method can precisely predict the distribution of velocity, pressure and concentration of most models. Its average prediction accuracy, evaluated by RMSE, and compared with CFD results, stands at 97%, 98.5% and 98.4% for the three components of velocity, and 96.7% and 99.5% for pressure and concentration, respectively.

-

(3)

The modification proposed in this work does not change the feature of mesh-independence and zero-shot super-resolution of FNO. The modified FNO-based method can be trained on lower resolution dataset and evaluated on higher resolution dataset.

Because of the fast computation and the high prediction accuracy, the modified FNO-based method is expected to replace traditional CFD methods as an intelligent solver for the optimal design of membrane modules. The modified FNO-based method can quickly design optimal schemes for improving energy efficiency with respect to various feed conditions. And although the modified FNO-based method is purposed to solve UPMs problems in this work, its capability to resolve nonlinear channel flow and mass transfer model enables direct extension to other membrane systems, which have the similar fundamental problems. And we will compare the modified FNO-based method with other deep learning methods in the future. However, generalization of this method is limited by the data-driven method. In addition, the use of linear interpolation to change unstructured data to structured data may lead to the loss of information, which will make the prediction less accurate in problems which focus on details, such as the prediction of concentration. Future improvements to this method could be:

-

(1)

Adding physical information constraints to the modified FNO-based method to improve the generalization ability of the method, and incorporating flow field predictions into concentration network to further improve the accuracy of concentration prediction.

-

(2)

Adding layer normalization to the network and adjusting weights in the loss function for fluid flow problem to further improve the accuracy of prediction.

-

(3)

Exploring improved methods to interpolate unstructured data into structured data, such as radial basis functions interpolation48. Alternatively, investigating point cloud input methods by leveraging techniques from point cloud transformer (PCT)49 and voxel set transformer50, where point clouds are processed by coordinate-based input embedding and neighbor embedding, or voxelized to extract voxel features.

Methods

3D multi-physics modeling

In this work, the multi-physics problem of RO includes nonlinear channel flow and mass transport. Navier–Stokes equations and diffusion-convection equation are applied to describe the fluid flow

and mass transfer characteristics.

where ρ (kg m−3) and μ (Pa s) are the density and viscosity of the fluid. u (m s−1) is the velocity vector. p (Pa) denotes hydraulic pressure. The design parameter vectors \({\boldsymbol{\gamma }}\) consist of geometric parameters \({{\boldsymbol{\beta }}}_{1}=[{L}_{{\rm{tot}}},{D}_{1,{\rm{A}}},{D}_{2,{\rm{A}}},{D}_{1,{\rm{B}}},{D}_{2,{\rm{B}}},{D}_{{\rm{tot}}},\alpha ]\) and average inlet velocity magnitude \({\bar{u}}_{{\rm{ave}},{\rm{in}}}={U}_{0}\) in this work, while \({L}_{{i},{\rm{A}}}={L}_{{i},{\rm{B}}}(i=1,2,3,4,5)\) are assumed to be constant and \({L}_{{\rm{tot}},{\rm{A}}}={L}_{{\rm{tot}},{\rm{B}}}={L}_{{\rm{tot}}}\). \({D}_{{\rm{s}}}\) (m2 s−1) and c (mol m−3) denote diffusivity and molar concentration. \({\varGamma }_{\cdot }\) represents the boundary, and the specific boundaries are shown in Supplementary Fig. S4.

Supercomputing-accelerated 3D CFD simulations

In our previous work39, a Latin hypercube sampling-like method was used to obtain more representative samples \({\boldsymbol{\gamma }}\) from the design parameters space. The CFD models include flow and mass transport governed by the Navier–Stokes equations under laminar flow conditions (Eq. (1)) and the convection–diffusion equation (Eq. (2)), respectively. There is a trade-off between computational efficiency and computational time because computational time can be reduced but it will lead to the decrease of computational efficiency as the increase of computational nodes. Our previous work39 indicated that it was a good choice for parallel solution of each 3D CFD model using 4 computational nodes in order to balance computational efficiency and computational time. The maximum computational scale can reach about 3840 nodes, and the total computational time for 960 3D multi-physics models is significantly reduced by more than 3000 times using the high throughput computing strategy.

The modified FNO-based method

FNO27 learns the mapping between two infinite dimensional spaces from the data of finite input-output pairs. In the event of the observations \({\{a{}_{j},{u}_{j}\}}_{j=1}^{N}\), where \({a}_{j}\sim \mu\) is an i.i.d. sequence from the probability measure µ supported on \({{A}}\), sequence \({u}_{j}={G}^{\dagger }({a}_{j})\) is possibly tampered with noise. There could be a parametric map constructed to build an approximation of \({G}^{\dagger }\), where \({G}^{\dagger}:{{A}}\to {{U}}\) is the nonlinear map and can be used to express the solution operator of a PDE,

By applying neural network minimize loss functions \({{C}}:{{U}}\times {{U}}\to {\mathbb{R}}\),

we can obtain the representation of the solution operator.

The framework of FNO proposed by Li et al. 27 firstly maps the input data to the high-dimensional space through the fully connected layer. Then it extracts the data through several Fourier layers, and finally reduces the dimensionality to the required output function space. However, the existence of fully connected layers makes FNO unable to deal with different sizes of data. Therefore, the fully connected layers are replaced with convolution layers whose convolution kernel is 1 × 1 × 1. The modified framework is shown in Fig. 1.

The transformation in the Fourier layer is defined as27,

where \(\sigma\) denotes the activation function and GELU function is used as the activation function in this work. Moreover, the number of Fourier layers is set to be 4. A 1 × 1 × 1 convolution layer is used to transform input data \({\it{a}}({\it{x}})\) to \({\it{v}}({\it{x}})\), while the number of output channels is 32. The output data \({\it{u}}({\it{x}})\) is transformed by two 1 × 1 × 1 convolution layers. The number of output channels in the first convolution layer is 128, while the second convolution layer is related to the predicted model.

The loss function \({{{L} }}({u}_{{\rm{true}}},{u}_{{\rm{pred}}})\) is defined by27,

where \({u}_{{\rm{pred}}}\), \({u}_{{\rm{true}}}\) denote the predicted result of the modified FNO-based method and the computational result of CFD, respectively. M represents the total number of data points in dataset. Since the concentration in this problem only changes over a small range in the z direction, fluid flow and mass transfer are trained by two different networks. The network of fluid flow predicts the distribution of the three components of velocity and pressure. And mass transfer predicts the distribution of concentration. Geometry, inlet velocity and coordinates serve as inputs to the fluid flow network, while the mass transfer network uses geometry, initial concentration, inlet velocity and coordinates as input. The loss functions of the two networks are set as,

where \(\hat{\bullet }\) denotes the predicted result of the modified FNO-based method, and the other denotes the computational result of CFD.

Data preparation details

In order to construct structured data input, linear interpolation is applied with the interval of \(\varDelta x=\frac{0.044}{200}\ \rm{m},\varDelta y=\frac{0.0078}{100}\ \rm{m},\varDelta z=\frac{0.001}{50}\ \rm{m}\) in the prediction of fluid flow. To reflect the data variation in a small range in the prediction of mass transfer, as shown in Supplementary Fig. S5(a), logarithmic intervals are used for interpolation in the z direction. Specifically, logarithmic intervals are intervals small at both ends and large in the middle, as shown in Supplementary Fig. S5(b). And the other two directions still use the same intervals as fluid flow.

Since the size of each model used in this work is quite different, the truncated modes in the Fourier layers are selected by the smallest size, and set as \(mod{e}_{{\rm{x}}}=16\), \(mod{e}_{{\rm{y}}}=6\), \(mod{e}_{{\rm{z}}}=8\).

Model train and inference speed

The Adaptive moment estimation (Adam) optimizer51 is applied to update the network parameters with the learning rate lr = 0.001, and the regularization coefficient \(\lambda ={10}^{-4}\). The learning rate is set to reduce to 50% every 50 iterations. The number of epochs in this work is set to 500.

When training the modified FNO-based model, Windows 10 is used as the operating system, and Intel(R) Xeon(R) CPU E5-2640 v4 and NVIDIA GeForce RTX 2080 Ti GPU are configured. Each epoch takes about 40 s. When predicting the modified FNO-based model, Windows 11 operating system is selected as the operating system, and Intel(R) Core (TM) i7-8700 CPU and NVIDIA GeForce GTX 1060 GPU are configured. The experimental results show that the average prediction time of each model is only 0.04 s, which fully demonstrates the efficient performance of the model.

Data availability

The datasets that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The code of the modified FNO-based method and the trained models are available at https://github.com/YanjinLiu/The-modified-FNO-based-method/tree/master.

References

Kochkov, D. et al. Machine learning–accelerated computational fluid dynamics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 118, e2101784118 (2021).

Ge, W. et al. Discrete simulation of granular and particle-fluid flows: from fundamental study to engineering application. Rev. Chem. Eng. 33, 551–623 (2017).

Yao, Q., Li, Q., Huang, J. & Jahanshahi, H. PDE-based prescribed performance adaptive attitude and vibration control of flexible spacecraft. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 141, 108504 (2023).

Neumann, P. et al. Assessing the scales in numerical weather and climate predictions: will exascale be the rescue? Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 377, 20180148 (2019).

Shannon, M. A. et al. Science and technology for water purification in the coming decades. Nature 452, 301–310 (2008).

Wang, J. et al. A critical review of transport through osmotic membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 454, 516–537 (2014).

Yang, Y. et al. Large-area graphene-nanomesh/carbon-nanotube hybrid membranes for ionic and molecular nanofiltration. Science 364, 1057–1062 (2019).

Cheng, C., Iyengar, S. A. & Karnik, R. Molecular size-dependent subcontinuum solvent permeation and ultrafast nanofiltration across nanoporous graphene membranes. Nat. Nanotechnol. 16, 989–995 (2021).

Tang, C., Zhao, Y., Wang, R., Hélix-Nielsen, C. & Fane, A. Desalination by biomimetic aquaporin membranes: Review of status and prospects. Desalination 308, 34–40 (2013).

Shen, J. et al. Fast water transport and molecular sieving through ultrathin ordered conjugated-polymer-framework membranes. Nat. Mater. 21, 1183–1190 (2022).

Itoh, Y. et al. Ultrafast water permeation through nanochannels with a densely fluorous interior surface. Science 376, 738–743 (2022).

Tan, Z., Chen, S., Peng, X., Zhang, L. & Gao, C. Polyamide membranes with nanoscale Turing structures for water purification. Science 360, 518–521 (2018).

Fane, A. G., Wang, R. & Hu, M. X. Synthetic membranes for water purification: status and future. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 3368–3386 (2015).

McGovern, R. K. & Lienhard V, J. H. On the asymptotic flux of ultrapermeable seawater reverse osmosis membranes due to concentration polarisation. J. Membr. Sci. 520, 560–565 (2016).

Sreedhar, N., Thomas, N., Ghaffour, N. & Arafat, H. A. The evolution of feed spacer role in membrane applications for desalination and water treatment: a critical review and future perspective. Desalination 554, 116505 (2023).

Shi, B., Marchetti, P., Peshev, D., Zhang, S. & Livingston, A. G. Will ultra-high permeance membranes lead to ultra-efficient processes? Challenges for molecular separations in liquid systems. J. Membr. Sci. 525, 35–47 (2017).

Elimelech, M. & Phillip, W. A. The future of seawater desalination: energy, technology, and the environment. Science 333, 712–717 (2011).

Sobana, S. & Panda, R. C. Identification, modelling, and control of continuous reverse osmosis desalination system: a review. Sep. Sci. Technol. 46, 551–560 (2011).

Russell, T. F. & Wheeler, M. F. Finite element and finite difference methods for continuous flows in porous media. In The mathematics of reservoir simulation. Frontiers in applied mathematics, 35–106 (Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics, 1983).

Moukalled, F., Mangani, L. & Darwish, M. The finite volume method. In The finite volume method in computational fluid dynamics: an advanced introduction with OpenFOAM® and Matlab, 103–135 (Springer International Publishing, 2016).

Reddy, J. N. Introduction to the finite element method, 4th ed. (McGraw-Hill Education, 2019).

Kwak, D., Kiris, C. & Kim, C. S. Computational challenges of viscous incompressible flows. Comput. Fluids 34, 283–299 (2005).

Krüger, T. et al. The lattice Boltzmann method - principles and practice (Springer International Publishing AG, 2016).

Shadloo, M. S., Oger, G. & Le Touzé, D. Smoothed particle hydrodynamics method for fluid flows, towards industrial applications: Motivations, current state, and challenges. Comput. Fluids 136, 11–34 (2016).

Santos, J. E. et al. PoreFlow-Net: A 3D convolutional neural network to predict fluid flow through porous media. Adv. Water Resour. 138, 103539 (2020).

Sirignano, J. & Spiliopoulos, K. DGM: A deep learning algorithm for solving partial differential equations. J. Comput. Phys. 375, 1339–1364 (2018).

Li, Z. et al. Fourier neural operator for parametric partial differential equations. In Proceedings of 9th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR, 2021).

Guo, X., Li, W. & Iorio, F. Convolutional neural networks for steady flow approximation. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD international conference on knowledge discovery and data mining, 481–490 (ACM, 2016).

Kamrava, S., Tahmasebi, P. & Sahimi, M. Physics- and image-based prediction of fluid flow and transport in complex porous membranes and materials by deep learning. J. Membr. Sci. 622, 119050 (2021).

Raissi, M., Perdikaris, P. & Karniadakis, G. E. Physics-informed neural networks: a deep learning framework for solving forward and inverse problems involving nonlinear partial differential equations. J. Comput. Phys. 378, 686–707 (2019).

E, W. & Yu, B. The deep Ritz method: a deep learning-based numerical algorithm for solving variational problems. Commun. Math. Stat. 6, 1–12 (2018).

Lu, L., Jin, P., Pang, G., Zhang, Z. & Karniadakis, G. E. Learning nonlinear operators via DeepONet based on the universal approximation theorem of operators. Nat. Mach. Intell. 3, 218–229 (2021).

Long, J., Shelhamer, E. & Darrell, T. Fully convolutional networks for semantic segmentation. In Conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 3431–3440 (CVPR, 2015).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Spatial pyramid pooling in deep convolutional networks for visual recognition. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 37, 1904–1916 (2015).

Zaremba, W., Sutskever, I. & Vinyals, O. Recurrent neural network regularization. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1409.2329 (2014).

Vaswani, A. et al. Attention is all you need. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 30 (NeurIPS, 2017).

Dosovitskiy, A. et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: transformers for image recognition at scale. In Proceedings of 9th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR, 2021).

Hatamizadeh, A. et al. Unetr: transformers for 3d medical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF winter conference on applications of computer vision, 574–584 (IEEE, 2022).

Luo, J., Li, M., Hoek, E. M. V. & Heng, Y. Supercomputing and machine learning-aided optimal design of high permeability seawater reverse osmosis membrane systems. Sci. Bull. 68, 397–407 (2023).

Luo, J., Li, M. & Heng, Y. A hybrid modeling approach for optimal design of non-woven membrane channels in brackish water reverse osmosis process with high-throughput computation. Desalination 489, 114463 (2020).

Li, M. & Noh, B. Validation of model-based optimization of brackish water reverse osmosis (BWRO) plant operation. Desalination 304, 20–24 (2012).

Deng, Z. et al. Temporal predictions of periodic flows using a mesh transformation and deep learning-based strategy. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 134, 108081 (2023).

Xie, G., Luo, J., Huang, M. & Heng, Y. Establishment of MLP models for the three-dimensional transport process in reverse osmosis desalination based on high-throughput computing (in Chinese). Chin. Sci. Bull. 68, 1–12 (2023).

Zhou, W., Bovik, A. C., Sheikh, H. R. & Simoncelli, E. P. Image quality assessment: from error visibility to structural similarity. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 13, 600–612 (2004).

Luo, J., Li, M. & Heng, Y. Bio-inspired design of next-generation ultrapermeable membrane systems. npj Clean Water 7, 4 (2024).

Rashid, M. M., Pittie, T., Chakraborty, S. & Krishnan, N. M. A. Learning the stress-strain fields in digital composites using Fourier neural operator. iScience 25, 105452 (2022).

Qin, S. et al. Toward a better understanding of fourier neural operators: analysis and improvement from a spectral perspective. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2404.07200 (2024).

Skala, V. RBF interpolation with CSRBF of large data sets. Proc. Comput. Sci. 108, 2433–2437 (2017).

Guo, M. H. et al. Pct: Point cloud transformer.Computational Vis. Media 7, 187–199 (2021).

He, C., Li, R., Li, S. & Zhang, L. Voxel set transformer: a set-to-set approach to 3d object detection from point clouds. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 8417–8427 (IEEE, 2022).

Kingma, D. & Ba, J. Adam: a method for stochastic optimization. In Proceedings of 3rd International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR, 2015).

Acknowledgements

Yi Heng acknowledges support provided by “Key-Area Research and Development Program of Guangdong Province, China” (No.2021B0101190003) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82430108). Jiu Luo thanks support provided by the Opening Project of Guangdong Province Key Laboratory of Computational Science at the Sun Yat-sen University (No. 2024014). We thank Jianghang Gu for assistance in the improvement of the methodology in this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yanjin Liu designed the research program, trained the modified FNO-based method, and wrote the original draft. Jiu Luo performed the computational simulations and wrote the original draft. Hong Liu, Zhiwei Wang and Mingming Huang contributed to the improvement in methodology and revised the manuscript. Yi Heng formulated the research goals, wrote the original draft, improved the visualization/data presentation, revised the manuscript, and provided computational resources.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Y., Luo, J., Huang, M. et al. Millionfold accelerated AI solver for 3D multi-physical simulations of ultrapermeable membranes. npj Clean Water 8, 59 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41545-025-00491-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41545-025-00491-1