Abstract

The development of stimuli-responsive membranes, often stated as smart membranes, has garnered increasing attention in recent years owing to their potential in various industrial separation processes and their ability to mimic natural biological systems. Materials suitable for such applications can dynamically adjust their physical and chemical properties, reacting to external stimuli such as temperature, pH, light, or magnetic/electric fields, thereby enabling precise control over membrane microstructure and the dynamic transport of molecules. This review offers an in-depth examination of the chemistry and responsive mechanisms of different stimuli-responsive materials, along with their integration into membrane matrices to optimize performance. Furthermore, it presents a comparative analysis of various types of stimuli-responses, illustrated with pertinent examples. Ultimately, this review highlights the outstanding challenges and future strategies for advancing smart membranes. With ongoing progress in chemistry and materials science, the development of a selective and efficient nanofiltration membrane platform is anticipated to yield significant benefits to advanced separation processes, offering more efficient and integrated technological solutions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

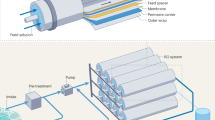

Membrane-based technologies stand as a powerful solution for removing trace amounts of emerging contaminants (ECs), including pharmaceutical, organic pollutants, nanomaterials, and personal care products, addressing the challenges posed by rapid industrialization and urbanization through innovative and determined approaches1. These processes offer advantages such as scalability, high selectivity, a compact design, and cost efficiency. Membranes can be engineered to specifically target pollutants based on factors like size, charge, and chemical characteristics, achieving high removal efficiencies for various ECs. Furthermore, membrane processes are economical, requiring minimal chemical use, reducing the generation of harmful byproducts and simplifying the treatment process. Common membrane types used in wastewater treatment include reverse osmosis (RO), microfiltration (MF), nanofiltration (NF), ultrafiltration (UF), and membrane bioreactors (MBRs), all of which have effectively removed ECs from domestic and industrial wastewater2.

Stimuli‑responsive materials have begun to redefine membrane science by embedding dynamic “on‑demand” behavior into otherwise static nanofiltration architectures. When molecules such as thermo, pH‑, photo‑, magnetic‑, or redox‑responsive polymers are grafted onto a porous scaffold, the resulting hybrid can reversibly reshape its pore geometry, alter surface charge, or switch interfacial wettability whenever an external cue is applied3,4. This capacity to dial flux and selectivity up or down in real time supplies a level of process control that conventional membranes—whose permeability is fixed at the moment of fabrication cannot match.

That tunability is now being harnessed across virtually every separation landscape. In water remediation, CO2 bubbling, magnetic fields or near‑infrared light trigger instantaneous wettability flips or pore shrinkage, collapsing oil‑in‑water‑in‑oil and water‑in‑oil‑in‑water emulsions in a single pass and initiating self‑cleaning cycles that arrest organic or biofouling5,6,7,8. At the biomedical scale, thermoresponsive or pH‑responsive networks open and close nanopores with sub‑micron precision, enabling pulsatile drug release, size‑selective protein harvesting, and dynamically stiffening tissue scaffolds9. Photochromic or gas‑binding motifs integrated into industrial membranes provide light‑gated O₂/N₂ partitioning and CO₂/H₂ capture without the energy penalties of cryogenic or pressure‑swing methods, offering a sustainable alternative for chemical and energy plants5,9. Meanwhile, food‑processing and pharmaceutical lines exploit charge‑switchable composites to purify peptides, vitamins and active pharmaceutical ingredients at kilogram‑per‑hour scales with previously unattainable yields, slashing solvent use and waste generation10.

Across these disparate arenas, the common thread is a membrane that cycles through multiple permeability states without structural fatigue, positioning stimuli‑responsive platforms as indispensable tools for cleaner, more precise, and resource‑efficient separations in the decades ahead11.

Several reviews have explored advancements in stimuli-responsive membranes, focusing on their fabrication processes and applications3,12,13,14,15,16,17. A recent review emphasizes the development of smart membranes that adjust their performance in response to stimuli and discusses their applications across fields like environmental protection, medicine, and energy15. Additionally, there is a paper addressing advances in stimuli-responsive membranes for nanofiltration, covering their preparation methods, classifications, and the challenges and future directions in this area16. Another review highlights membranes that adapt their properties to improve separation performance through various stimuli such as ions, light, pH, temperature, and electric or magnetic fields. It also details preparation techniques like blending, casting, polymerization, self-assembly, and electrospinning17. Despite substantial progress in understanding external triggers, there remains a notable gap in knowledge regarding the molecular chemistry underlying these materials, including the structure of responsive materials and interactions and their influence on membrane performance for building smarter and more efficient nanofiltration/ultrafiltration membrane platforms.

In this review, we concentrated on how the chemistry of stimuli-responsive materials can be modified to achieve specific functional changes in membrane characteristics such as permeability, wettability, and flux. This review also explores the molecular mechanisms by which the chemical structure and composition of materials affect their ability to respond to external stimuli. By analyzing existing fabrication techniques and material integration strategies, we address the critical challenges in durability and scalability, providing insights into future directions for exploiting these smart materials in industrial and biomedical fields. The review sections will primarily examine materials exhibiting responsiveness to light, electricity, pH, and temperature, as well as the membranes they facilitate. In addition, we will investigate the existing research gaps in membrane development strategies by comparing various categories of stimuli-responsive materials based on their distinct chemistries and their integration into membrane matrices. Ultimately, we will propose strategies for enhancing the scalability of responsive membranes across diverse fields (Fig. 1).

Light-responsive materials

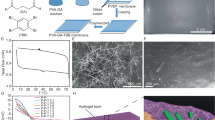

Light-responsive molecules are materials that undergo reversible structural changes when exposed to specific wavelengths of light. These molecules can switch between two or more isomeric forms with distinct physical and chemical properties. The structural changes are typically triggered by the absorption of light energy, causing molecular rearrangements such as isomerization, cyclization, or bond breaking/forming. Their exceptional capacity for reversible transformations in response to light exposure is a phenomenon that holds significant implications for the development of advanced materials. Table 1 compares different light-responsive materials (azobenzenes, spiropyran, anthracene, diarylethene, and stilbenes) in terms of their structure, activation energies, isomerization types, and wavelengths. A detailed comparative description of their respective chemistries and light-dependent responsive behavior mechanisms is given in supporting information.

In this section, the use of light-responsive materials to create smart membranes will be discussed, and how the responsive behavior of different materials affects the selectivity, efficiency, wettability, and permeability of membranes. Mechanisms of light activation of various molecules are presented in Figs. S1 and S2.

Light-responsive molecules enabled membranes

Light-responsive molecules have revolutionized the design of functional membranes by introducing the ability to modulate membrane properties dynamically and reversibly through light stimuli18,19,20. These specialized membranes, activated by light, exhibit tunable permeability, selectivity, and surface properties, enabling precise control over molecular transport and separation processes. By incorporating light-responsive molecules such as azobenzenes, spiropyrans, and diarylethenes, these membranes offer unique advantages in fields requiring on-demand regulation, such as chemical separations and environmental applications. The versatility and non-invasive nature of light as a stimulus make these membranes particularly attractive for advanced material applications21,22.

The membrane pore size is a critical factor for achieving optimal separation performance in membranes, as it directly influences the efficiency and selectivity of the separation process. Azobenzene is particularly advantageous due to its high responsiveness to light stimuli. Light-responsive covalent organic network (CON) membranes were developed through the interfacial polymerization of azobenzene-4,4′-dicarbonyl dichloride (AB) and 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane (cyclen) under optimized conditions (Table 2, entry 1)23. These membranes are utilized in the selective separation and removal of dye by controlling the trans-cis isomerization under UV/Visible light exposure. The trans membranes resulted in an “on” state with larger membrane pore apertures of around 1.06 nm, while UV light exposure induced cis membranes, shrinking the pore sizes to around 0.75 nm in the “off” state (Fig. 2). Due to their sizes, the trans-CON membranes demonstrated permeance of 22.6 L/m2/h/bar and rejected indigo carmine with 94.7% efficiency. Upon UV irradiation, the membrane permeance was reduced to 19.3 L/m2/h/bar in the cis state. The process of photoisomerization facilitates a significant geometrical transformation in azobenzene compounds. Specifically, it transitions from the planar trans-azobenzene form, which measures ~9 Å, to the nonplanar cis-azobenzene configuration, which is about 6 Å in size. In the CON, the cyclen ring is subjected to tension, causing it to transition from a zigzag conformation to a planar conformation. This alteration results in corresponding size modifications from 3.4 Å to 4.5 Å, while the azobenzene unit experiences a reduction in size from 9 Å to 6 Å. This critical transformation allows for the direct conversion of light energy into various mechanical motions, such as bending, oscillation, and twisting. These mechanical phenomena play a crucial role in altering the structural dynamics of materials, leading to the expansion and bending of pores within a membrane. Consequently, this alteration affects the membrane’s permeation capability. The isomerization of light-responsive azobenzene units provides a larger geometric change. In CON membranes, this light-responsive characteristic allows pores to switch between open and closed states, allowing for accurate molecular sieving of dyes while maintaining high solvent permeability. Under UV light, the cis form (off state) produces smaller pore diameters, leading to greater dye rejection than the trans form (on state), which has larger pores.

Schematic illustration of the trans-to-cis and cis-to-trans photoisomerization, along with the chemical structures of light-responsive membranes23. Permission to reprint granted.

The trans-to-cis photoisomerization occurred rapidly within 5 min of UV exposure, while the reverse cis-to-trans isomerization required around 30 mins under visible light, enabling reversible remote control over molecular sieving capability. Light-responsive (PAN/Azo-MPEG/Azo-PHMB) thin-film membranes were developed to enhance separation efficiency and improve fouling resistance (Table 2, entry 2)24. The performance of the PAN/Azo-MPEG/Azo-PHMB membrane was outstanding, with a high-water permeability of 17.9 L/m2/h/bar and an impressive flux recovery ratio (FRR > 90%) even after multiple antifouling tests. Additionally, the membrane demonstrated high selectivity, particularly favoring divalent over monovalent salts, with a selectivity ratio of αMgSO₄/NaCl = 33.4. The functional layer of the membranes could be regenerated using ultraviolet (UV) light, ensuring sustained performance even after contamination. Furthermore, the membrane showed high rejection rates for the antibiotics erythromycin (ERY) while allowing significant passage of NaCl, making it ideal for applications in antibiotic separation from salt/antibiotic mixtures. Even after the fourth cycle, the membrane maintained low flux loss and high flux recovery, which can be attributed to the functional polymers’ hydrophilic nature and spatial repulsion properties.

The development of self-cleaning ultrafiltration (UF) membranes was achieved by co-depositing photo-mobile 4,4′-azodianiline (AZO) and bio-adhesive polydopamine (PDA) (Table 2 entry 3)25. These membranes show photoresponsive behavior in the presence of UV/Vis light irradiation. This process mitigated foulant aggregation and significantly enhanced the surface hydrophilicity, demonstrated by a decrease in water contact angle (WCA) from 39° to 29°. The combination of PDA and AZO in the coating layer provided robust adhesion to the membrane surface while preventing pore blockage, ensuring high water permeance. The modified membrane demonstrated outstanding self-cleaning ability, with a 160% increase in water permeance following UV/visible light exposure, even when contaminated with bovine serum albumin (BSA). This strategy presents a promising pathway for creating membranes with better fouling resistance and long-term, sustainable performance, especially in water purification applications that require frequent cleaning.

The thin-film membranes (SulfAzo3TB/PES) were designed to provide light-responsive control over water permeability and molecular separation (Table 2, entry 4)26. These membranes exhibited a high-water permeability, with a permeance variation of 0.78 L/m2/h/bar in the cis state and 0.64 L/m2/h/bar in the trans-state, demonstrating their reversible tunability. The membranes showed selective molecular weight cut-off (MWCO) variation, shifting from 2000 g/mol in the trans-state to 4000 g/mol in the cis state. The light-responsive properties of the membranes enabled easy regeneration through UV/visible light exposure, maintaining high performance and permeability over multiple cycles. Furthermore, the membranes demonstrated high rejection rates for larger organic molecules like Rhodamine B, while allowing smaller molecules to pass, making them ideal for applications requiring size-selective filtration. The light-responsive switching ability of azobenzene has been used effectively for oil-water separation. In this method, azobenzene groups were attached to SiO₂-modified polypropylene (PP) membranes through a straightforward chemical grafting process (Table 2, entry 5)27.

The grafted chromophore, 7-[(trifluoromethoxyphenylazo)phenoxy]pentanoic acid (CF₃AZO), adopts the thermodynamically stable trans configuration under ambient conditions, imparting a super-hydrophobic WCA of ≈160°. Exposure to 365 nm UV light drives a rapid trans → cis photo-isomerisation; the higher surface free energy of the cis form collapses the WCA to ≤5°, producing a super-hydrophilic surface. Re-illumination with visible light at 440 nm restores the trans-state and the original super-hydrophobicity, completing a fully reversible cycle that can be repeated for many hundreds of switching events without fatigue. This membrane delivers outstanding performance in separating oil from water, with 98.7% efficiency 98.7% efficiency and a high flux of 2352 L/m2/h, which increases to 2653 L/m2/h for oil permeation under visible light. It exhibits excellent physical and chemical stability, retaining its performance in harsh conditions and after repeated mechanical stress and rinsing. Its mechanical flexibility and durability make it an ideal material for sustainable and efficient industrial oily water separation.

To further improve self-cleaning and desalination properties, the thin-film composite membranes (0.10%-PPy@G-CN/HCPAM) were developed (Table 2, entry 6)28. These membranes demonstrated excellent performance, achieving a high-water flux of 78.57 L/m2/h at 25 bars with nearly complete rejection of Eriochrome Black T (EBT) dye at 99.90%. Another light-responsive nanofiltration membrane was developed using a covalent organic framework composite (β-CD/AZO COF/HPAN) membrane, incorporating azobenzene (AZO) functional groups to create light-gated molecular channels (Table 2, entry 7)29. The membrane performance improves under 365 nm UV irradiation, where the permeance increases from 19.56 L/m2/h/bar to 42.30 L/m2/h/bar, and the dye rejection of Rose Bengal (RB) rises from 94.40% to 99.12%. The UV-triggered trans-to-cis isomerization of AZO leads to adjustable pore sizes, enhancing the membrane’s molecular sieving capabilities. The membranes exhibit excellent antifouling properties, with a fouling recovery rate (FRR) improving by 17% under UV exposure related to the higher hydrophilic nature and reduced pore size of the membranes.

Light-responsive azobenzene molecules were also introduced into the pores of a COF membrane made from 1,3,5-triformylbenzene (Tb) and 4,4′-diaminobenzanilide (Da), as shown in Fig. 3A (Table 2, entry 8)30. The resulting light-responsive COF membranes, with highly ordered and fine TbDa-Azo channels, demonstrated efficient sieving ability for monovalent and multivalent ions by acting as a gate to achieve selective cation filtration. In the trans conformation, the Azo groups contributed to a pore size of ~1.07 nm, while in the cis conformation, it is ~1.42 nm. TbDa-Azo COF membranes are durable in prolonged permeation of ions (Fig. 3B). When exposed to 365 nm and 450 nm light, the membrane becomes impermeable because the pore size of the TbDa-Azo COF membrane roughly matches the diameter of hydrated Al³⁺ ions. Deformation of the hydration shells permits Al³⁺ to enter the membrane pores (Fig. 3C). The TbDa-Azo COF membrane’s water flux can be shifted between ~3.1 and ~7.5 L/m2/h under exposure to light with different wavelengths. The fine-tuned separation of the penicillin/Al3+ mixture is attained upon gradual and short-time exposure to UV light, and the retention of Al3+ is triggered by the membrane under visible light radiation for a short duration of 3 min (Fig. 3D). Azobenzene groups were also grafted onto PMMA, which was then incorporated into a P(VDF-CTFE) polymer backbone (Table 2, entry 9)31. The resulting membrane exhibited reversible changes in pore size and surface hydrophilicity in response to light, with UV irradiation causing pore expansion and increased hydrophilicity, thereby significantly improving backflushing efficiency. The light-triggered process recovered over 90% of irreversible fouling, such as BSA, allowing for precise molecule release based on size. Azobenzene-grafted GO-PVDF membranes exhibited light-responsive behavior in the presence of UV/Vis light (Table 2, entry 10)32. The trans membranes exhibited an MB permeance of 132 L/m/h/bar and achieved near-complete rejection of methylene blue (MB) dye, attributed to size exclusion mechanisms. In another study, the light-responsive molecules were attached to alumina membranes using a covalent condensation reaction (Table 2, entry 11)33. In this study, MB dye was completely rejected in the trans-state, while in the cis-state, it was not completely rejected due to the size of the molecules.

A Synthesis of 1,3,5-triformylbenzene (Tb)–4,4′-diaminobenzanilide (Da) compound (TbDa) and TbDa-Azo compound. B Representation of the photo induced mass transport behavior. C Multistep manipulation of AI separation factor applying UV/Visible light. Adapted with permission from ref. 30. Permission to reprint granted.

A light-responsive spiropyran (SP) moiety was incorporated into polyamide thin-film composite nanofiltration (NF) membranes in a single-step process, facilitated by low-energy electron beam treatment (Table 2, entry 12)34. Another work integrated SP onto graphene oxide-based NF membranes (Table 2, entry 13)35. When exposed to UV radiation, SP converts into zwitterionic merocyanine, resulting in water permeation rates of ~6.5 L/m²/h/bar. Exposure to visible light reverted merocyanine back to SP, resulting in a water flux of ~5.25 L/m²/h/bar. These modified NF membranes outperformed unmodified membranes in terms of chlorine tolerance and normalized water flux, while maintaining ion rejection capability.

SP-based membranes are produced by grafting poly(methacrylic acid) (PMAA) brushes onto polypropylene (PP) substrates via argon plasma-induced free-radical polymerization (Table 2, entry 14)36. Afterward, SP moieties are introduced into the polymer brushes through post-polymerization modification. The light-responsive membranes exhibit reversible changes in wettability and permeability in response to light stimuli. The PMAA-SP-modified membranes demonstrate efficient switching properties, with the SP groups enabling a transition between hydrophobic and hydrophilic states under UV and visible light, respectively. The pore sizes are reduced in the hydrophobic state, while in the hydrophilic state, the pores expand. These membranes maintain durability and performance over prolonged cycles of stimulus exposure. The water flux through the membranes can be adjusted between ~256 and ~405 L/m2/h/bar under alternating light conditions. SP molecular aggregates into graphene oxide (GO) structures exhibit significant potential in water purification due to their tunable permeability, enhanced separation performance, and self-cleaning capabilities (Table 2, entry 15)37. Incorporating SP aggregates enriches water transport channels and increases hydrophilicity, resulting in exceptional water fluxes, such as 95.0 L/m2/h/bar under visible light conditions. These membranes demonstrate superior rejection rates for various dye molecules, driven by size exclusion and electrostatic interactions38. Upon light exposure, the membrane transitions from hydrophobic to hydrophilic, reversing the fouling process. This mechanism allows the membrane to recover up to 96.2% of its initial permeability after fouling by organic pollutants like bovine serum albumin. The SP was also attached to PVDF via the NIPS method (Table 2, entry 17)39. Incorporating SP aggregates enriches water transport channels and increases hydrophilicity, resulting in exceptional water fluxes, such as 104 L/m2/h/bar under visible light conditions. These membranes maintain durability and performance over prolonged cycles of stimulus exposure.

Anthracene-based membranes are produced using poly(styrene-block-anthracene-block-methyl methacrylate) triblock copolymer through a self-assembly non-solvent induced phase separation method (Table 2, entry 18)40. The light-responsive anthracene groups undergo conformational changes upon light irradiation, which enables the membranes to exhibit efficient water flux and solute retention control. Under UV light at 365 nm, the anthracene groups form [4 + 4] cycloadducts, decreasing water flux from 310 to 250 L/m2/h/bar. This reduction occurs because the cycloadducts partially close the pores of the membrane. As expected, reversing the light exposure at 264 nm restores the original flux to 280 L/m2/h/bar. The highly ordered channels of the anthracene-based membranes act as gates, achieving selective permeability. The photo-dimerization and its reverse process happen quickly under UV light exposures, making these membranes highly responsive and durable over multiple irradiation cycles.

Light-responsive materials for membrane development and future directions

This section elucidates the comparison of different light-responsive molecules in terms of isomerization time (responsiveness) based on activation energies, structural modification, photostability, and processability behavior.

Based on activation energies, azobenzene is known for its fast photoisomerization between its cis and trans forms, occurring in just a few seconds due to its low activation energy (~50 kJ/mol). In contrast, diarylethene’s ring-opening and closing reactions take about 1 min due to a higher activation energy (~100 KJ/mol). Spiropyrans and stilbene exhibit slower responsiveness due to complex isomerization mechanisms and higher energy barriers13. Anthracene’s photodimerization process, requiring ~200 kJ/mol, is even slower, taking 20–60 mins and resulting in a much longer response time compared to other light-responsive molecules14.

Structural modification of light-responsive molecules is a key strategy for developing light-responsive membranes. Structural modification includes changes to the molecular backbone, the addition of functional groups, or alterations of side chains, each affecting light-responsive properties in distinct ways. For instance, azobenzene absorbs UV-A light in the 320–380 nm range and exhibits rapid photoisomerization due to low activation energy, which allows it to respond quickly15. Extending conjugated systems in azobenzene structure can shift absorption wavelengths (365 nm), isomerization kinetics and activation energy, thus controlling the water flux41. These structural adjustments influence the efficiency and wavelength of the light response and affect how the molecule interacts with the membrane matrix, impacting solubility, phase separation, and mechanical properties42. Spiropyrans also respond to UV-A light (350–400 nm) but have higher activation energy, resulting in slower isomerization16. In contrast, anthracene absorbs at 315–360 nm, needing even more energy for photodimerization, while stilbene, absorbing in the 280–320 nm range, shows lower responsiveness due to its complex isomerization mechanisms17. All these molecules show responsiveness under UV-A light, but the differences in activation energy led to varying reaction rates. The density of the functional groups is also a crucial strategy for enhancing the performance of light-responsive membranes. Higher concentrations of light-responsive units can lead to increased responsiveness and faster switching times, resulting in more pronounced changes in permeability upon light exposure. The density of functional groups can also influence the membrane microstructure and phase behavior, allowing for tailored permeability profiles and dynamic gating43.

Molecular size variation is another important strategy in designing photo-responsive membranes, significantly influencing their responsiveness, properties, and overall performance37. The size of light-responsive molecules is crucial for determining membrane effectiveness, as it affects their interaction with light and subsequent changes in membrane characteristics44. Smaller molecules allow for denser packing within the membrane matrix, enhancing light responsiveness and enabling rapid changes in permeability upon irradiation. Increasing the density of light-responsive molecules also influences membrane performance. Larger photo-responsive units provide structural stability and strength, which helps maintain functionality under varying operational conditions. However, these larger units may hinder the mobility of light-responsive sites, potentially resulting in slower response times. This relationship underscores the need for careful consideration in membrane design to balance responsiveness and structural integrity.

The multi-layer approach is an effective strategy for developing advanced light-responsive membranes by integrating various materials and functionalities. This approach involves stacking different photo-responsive materials, each selected for its unique properties and responsiveness to specific wavelengths of light. For example, a top layer of azobenzene can facilitate rapid switching and permeability changes, while a bottom layer of spiropyran enhances wettability and fouling resistance. This method improves mechanical stability and allows for the integration of light responsiveness with other external stimuli, like pH or temperature.

Photostability is another important parameter assessing the durability and effectiveness of light-responsive molecules. Diarylethene exhibits exceptional photostability in its closed-ring form, where it shows strong resistance to photo fatigue over many cycles (35 cycles) of light exposure18. On the other hand, azobenzene shows lower photostability due to UV light-induced photodegradation and thermal back-isomerization19. Anthracene, however, demonstrates high photostability through a reversible photodimerization process, where two anthracene molecules form a covalent bond. This dimerized form is stable and resistant to photodegradation, making anthracene suitable for applications that require long-term stability under UV light20. Stilbene and spiropyran exhibit lower photostability due to environmental sensitivity (pH and solvent polarity) and photodegradation, which reduces their durability under UV light exposure21.

The processability of light-responsive molecules varies significantly depending on their chemical structure and physical properties. Azobenzene materials are more processable and can be easily incorporated into various polymer matrices and other materials, creating materials with tunable properties22,23. For instance, azobenzene has the ability to form host-guest complexes with cyclodextrin; the stability of these complexes is dependent on the isomeric state of azobenzene25. This light-triggered isomerization allows for reversible switching between complexed and uncomplexed states, which has been used to build a variety of light-responsive materials25.

In contrast, spiropyran, while also processable, requires more careful handling due to its sensitivity to pH and solvent polarity, which can affect its functionality during processing26. Diarylethene is also challenging to process due to its rigid closed-ring structure, needing specialized techniques for dispersion in polymers, though it can enhance electro-switch characteristics when incorporated into conjugated polymers27. Lastly, anthracene’s slower photodimerization can lead to inefficiencies in manufacturing when rapid response times are desired28.

The development of light-responsive membranes critically depends on the rational design and structural modification of the photoactive molecules embedded within them. By tailoring the molecular architecture—such as the backbone rigidity, functional group density, and side chain composition—key properties including switching kinetics, activation energy barriers, and overall responsiveness can be precisely modulated. These parameters directly influence the membrane’s ability to undergo rapid and reversible transformations in permeability or surface wettability upon light exposure. Importantly, not only the molecular structure but also the spatial organization of light-responsive units within the membrane matrix plays a vital role. A periodic or ordered arrangement of these functional groups is expected to promote cooperative transitions and more efficient signal propagation across the material, whereas a random distribution may lead to diminished or heterogeneous responsiveness. This highlights the importance of supramolecular engineering strategies in membrane fabrication. In parallel, a major research focus is on creating inherently photo-responsive polymer systems that can be directly processed into membranes, eliminating the need for post-synthetic surface functionalization. Such materials would enable higher functional group density and uniformity, while simplifying the fabrication workflow. However, identifying polymers that combine sufficient photo-responsiveness with mechanical integrity and processability remains a significant challenge.

To translate these materials into real-world applications, light-responsive behavior must remain effective at larger membrane scales and under practical operating conditions. The switching performance must be stable over multiple light on/off cycles, and compatible with scalable manufacturing techniques such as roll-to-roll or layer-by-layer assembly. Potential applications include tunable membranes for selective molecular separation, on-demand drug delivery systems, light-triggered valves in microfluidic devices, and self-cleaning surfaces in water treatment modules. Future work should therefore focus on aligning molecular design with application-specific performance metrics and scalable fabrication methods.

Photo-responsive membranes for water treatment report high solar efficiencies alongside variable water flux and cost-performance metrics. Composite membranes using Ti₃C₂Tx MXene achieve water evaporation efficiencies of about 90%, while Janus membranes deliver ~92% solar energy utilization. Au nanoparticle-based composites reach up to 94.6% solar thermal conversion, and polydopamine-coated systems and carbon nanotube membranes exhibit light absorption values near 97% and 94%, respectively.

Cost information appears less consistently across studies. When measured, performance ratios include 62.35 g·h⁻¹ per dollar and $0.15 per kg·m⁻²·h⁻¹, while minimal use of expensive materials in AuNP systems is noted. In sum, these studies indicate that high solar efficiency and acceptable cost performance can be obtained with photo-responsive membranes, though differences in reporting preclude a fully standardized cost comparison. On a cost comparison basis, it can be said that high solar efficiency is achievable with a range of photo-responsive membrane materials, including those using minimal amounts of expensive components. However, only a few reports have provided quantitative cost data or cost-performance ratios. The available evidence suggests technical feasibility and potential for cost-effectiveness, but the lack of consistent economic and operational data precludes firm comparative conclusions.

Although, light-responsive materials offer great potential for the controlled release of substances from light-responsive membrane matrices. However, challenges remain, particularly with the availability of compatible light-responsive materials and two-dimensional materials for composite membrane fabrication. Additionally, the use of light may increase operational costs. Despite these hurdles, there are significant opportunities to improve the large-scale manufacturing and practical applications of such smart membranes with antifouling and self-cleaning properties. Key areas for improvement include enhancing photo-responsive efficiency and stability. Optimizing the membrane’s pore structure can strengthen interactions for better rejection and permeability. Further research on light-responsive membranes in photocatalytic membrane reactors can assess their stability and self-cleaning capabilities. Additionally, exploring pollutant removal mechanisms and how the positioning of the membrane module influences the effectiveness of light could enhance performance.

Electro-responsive materials (ERMs)

When subjected to external electrical impulses, electro-responsive materials can reversibly alter their microstructure, resulting in changes to their physical and chemical properties and enabling controlled, tunable performance in various applications. This section will explore the chemistry and adjustable properties of electro-responsive materials, including electrical conductivity, mechanical properties (such as swelling/stiffness), and conformational changes, which have been used to date for responsive membrane development. It will underscore both the challenges and improvement opportunities.

Electro-responsive polymers (ERPs)

Electro-responsive polymers (ERPs) possess the capability to transduce electrical energy into mechanical energy, such as swelling, shrinking, or bending under an applied voltage. They are a class of inherently conductive polymers with π-electron delocalization in their backbones, including polyanilines (PANIs), polythiophenes (PTs), and polypyrroles (PPys)45,46. A detailed description of their individual chemistries and electroresponsive behavior mechanisms is provided in the supporting information.

Although most ERPs share similar redox mechanisms, the total volume change of an ERP during redox switching depends on several interrelated effects, including change in charge density, electronic response of an electric double layer at the polymer-electrolyte interface, and osmotic expansion/redox interaction between electrolyte and ERP47. Changes in the charged density along the conductive polymer backbone result in the deformation of the polymer network, as the C-C bond length is altered, as shown in Figs. S3 and S4. This volume change occurs due to fluctuations in charge density during processes of oxidation or reduction. The electric double layer at the polymer-electrolyte interface reacts to alterations in the electronic state, also leading to conformational changes.

Osmotic expansion in electro-responsive polymers (ERPs) is caused by redox interactions between the conducting polymer and electrolyte molecules, which promote solvent flow and change the volume of the ERP matrix47. ERP actuation in electrochemical redox processes is enabled by the movement of mobile ions: in anion-driven systems, the polymer backbone loses electrons while anions are incorporated; in cation-driven systems, the backbone gains electrons and cations are taken up, as illustrated in Figs. S3A–C and S447,48,49.

Carbon-based materials and single molecules

Electro-responsive membranes made with carbon-based materials exhibit excellent conductivity due to their sp²-hybridized carbon atoms and delocalized π–π electron systems. These materials can function as either cathodes or anodes. For applications such as electrostatic repulsion, electrophoresis, and direct redox reactions, voltages below the oxygen evolution threshold of carbon electrodes are generally used50.

Carbon anodes have a potential for the oxygen evolution reaction generally below 0.4 V. They interact with electrogenerated hydroxyl radicals to partially oxidize organic compounds. They interact with electrogenerated hydroxyl radicals to partially oxidize organic compounds. Carbon nanotubes (CNTs) are commonly employed as conductive materials in electro-responsive membrane manufacturing due to their ability to create dense, interwoven structures with porosity and support high current densities of over 109A/cm² for metallic single-walled CNTs51. This structural configuration facilitates inter-tube bonding through van der Waals interactions, ensuring operational stability. Furthermore, graphene-based carbon materials also manifest advantageous electrical properties. The synthesis of a conductive layer through deposition results in a specific surface area and tunable pore size distribution. Introducing oxygen-containing groups allows CNT and graphene-based materials to interact with other metal catalysts, such as Pd and Fe. Moreover, mesh-type electrodes like carbon fiber cloth and carbon paper offer effective conductive platforms for membrane modification52.

MXenes, with their distinctive layered structure composed of alternating transition metal and carbon layers, are particularly attractive for electrocatalysis and energy storage fields. Their high electrical conductivity reaching up to 10,000 S/cm in the case of Ti₃C₂Tₓ enables rapid electron transport across the electrode material53. The surface functional groups and high specific surface area of MXenes provide numerous sites for anchoring active catalysts. Additionally, the surface of MXenes behaves like a transition metal oxide, making it redox-active, encouraging their use in electro-responsive membranes. However, during electrode fabrication, MXene nanosheets tend to cluster and self-assemble due to strong hydrogen bond interactions and van der Waals interactions, which can compromise their electrochemical performance. Single molecules that are electro-responsive can have their molecular energy levels adjusted when the gate electrode potential is maintained beyond the boundaries of the redox-active range. Upon entering the redox region, the molecules experience reversible electron transfer processes, which modify their energy states and the extent of conjugation54. Viologen and its derivatives are recognized for their conjugated structures, which enable electrical conductivity. The nitrogen atoms in their pyridine rings provide lone pairs that enhance electron transport. These molecules can cycle through three different oxidation states by reversibly transferring two electrons, making them valuable in technologies such as supercapacitors and redox flow batteries, where their response can be finely tuned by an applied electric field.

Viologens exist in various states, including dicationic, monocation radical, or redox couple, to meet diverse energy system requirements. The viologen dication interacts electrostatically with polysulfides in Li–S batteries, while its radical form helps inhibit lithium dendrite growth in Li-ion batteries55. Their redox behavior is advantageous in redox flow batteries, Li-air batteries, and supercapacitors, contributing to enhanced performance. This switchable redox state feature endows viologens and their derivatives with excellent cyclic reversibility, supporting their role in membrane development56.

These carbon-based frameworks and molecules also offer a unique platform for constructing electro-responsive membranes with tunable transport properties. When an external electric field is applied, charge redistribution at the conductive interface can dynamically alter the membrane’s surface charge density, wettability, and ion transport resistance. Furthermore, covalent or non-covalent integration of redox-active single molecules—such as viologens, ferrocene derivatives, or metal-organic complexes—onto CNT or graphene scaffolds allows for precise modulation of membrane behavior via reversible electron transfer processes. This integration enables programmable gating, selective ion rejection, or antifouling switching, making carbon-based systems ideal for next-generation membranes in separations, environmental remediation, and biointerfaces.

Electro-responsive enabled membranes

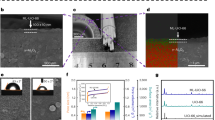

The ERMs can be integrated into the membrane matrix, chemically grafted to its structure, or coated onto the surfaces and pores of the membranes as presented in Fig. 457,58. This section will discuss how ERMs are incorporated into membranes to control permeability, rejection, wettability, catalytic degradation, and pore size under applied potential. Table 3 provides an overview of recent advances in electro-responsive membranes, however several challenges still need to be overcome.

A When a voltage is applied, the ERM interacts with contaminants through electrooxidation, electrostatic adsorption, and electrostatic repulsion. Electrooxidation is primarily responsible for water decontamination50. B The redox-responsive membrane transitions from a hydrophobic to a hydrophilic state upon the application of a voltage. This change facilitates the controlled transport of molecules and ions across the membrane166. Permission to reprint granted.

Polymer-based electro-responsive membranes

The electrical regulation of oxidation and reduction properties of HCl-doped PANI membranes containing different molecular weights of PANI in relation to the applied potential was studied59. In aryl amine polymers, when the pH is very low, anions enter the film during the oxidation and exit during the reduction. This movement may also carry solvent molecules, resulting in swelling and deswelling of the polymer60.

Applying a high potential can modify the conjugated framework by inducing oxidation and triggering the dopant migration, changing their binding sites or spatial arrangement within the polymer, and thereby modifying the membrane’s free volume. This morphological shift causes polymer chains to swell, in turn reducing the membrane’s free volume and pore size. As a result, this causes additional resistance to water transport, leading to a change in permeance at different applied voltages (Table 3, entry 1). The PANI membrane’s regulation mechanism is influenced by Donnan repulsion, which depends on surface charge, as well as by diffusion processes determined by its chemical characteristics. Acid or alkali doping can also control the porosity of PANI membranes. However, conventional small-acid doped PANI membranes offer limited chemical resistance and mechanical strength, limiting the stability, durability, and nanofiltration applications of membranes61. It was shown that exposure to acids may strongly weaken intermolecular interactions and eventually embrittle the membrane material61,62. To address these issues, the researchers opted for poly(2-acrylamido-2-methyl-1-propanesulfonic acid) (PAMPSA) as the acid dopant. In contrast to HCl, PAMPSA is a flexible polymeric acid with a bulky benzene sulfonyl group. SO₃H groups are covalently linked to benzene rings, which are responsible for stable hydrophilic modification and doping of the system. The strong covalent bond between the acid group and the benzene ring reduces acid leaching, while the dopant functions as a plasticizer, increasing the membrane’s mechanical strength.

The electrical conductivity of the PAMPSA-doped membrane showed no change when tested both before and after PEG filtration. In contrast, the conductivity of the HCl-doped membrane decreased significantly by four orders of magnitude following PEG filtration. This substantial difference in conductivity suggests that there is minimal leaching of the dopant in the PAMPSA-doped membranes. Electrically induced swollen polymer chains reduced the rejection of PEG to 32% for the PAMPSA-doped PANI membrane and to 95% for the HCl-doped membranes. The lesser rejection for PAMPSA-doped membranes indicated that the PANI-PAMPSA membrane has a more open structure than the PANI-HCl membrane. Larger dopants, such as PAMPSA, widen the intermolecular spacing among PANI polymer chains 6463. As a result, this facilitates the development of a looser membrane structure with larger pore sizes (Table 3, entry 2).

Nano-based electro-responsive membranes

One effective technique to enhance the rejection efficiency of the NF membrane involves reducing pore size or strengthening electrostatic interactions. However, this strategy has a disadvantage: smaller pore sizes increase rejection while decreasing permeability, which might reduce overall separation efficiency. In contrast, increasing electrostatic interactions might result in high rejection rates while maintaining permeability56.

Incorporating polystyrene (PSS) into the PANI@CNT membrane can significantly increase its surface charge density, increasing it from 11.9 to 73.0 mC/m257. The increased surface charge density under electrical assistance leads to improved ion rejection rates for both Na2SO4 (from 81.6% to 93.0%) and NaCl (from 53.9% to 82.4%), without sacrificing the water permeability of the membrane (Table 3, entry 3). The electrical assistance enhances the Donnan potential difference between the membrane and the bulk solution, which increases the ion transfer resistance and thus improves the ion rejection performance. Another group of researchers evaluated the membrane permeance and ion rejection performance of PANI-DBSA-CNT and PANI-PSSA-CNT membranes for NaCl and Na2SO4 under different applied electrical potentials58. PANI-PSSA-CNTs showed the highest surface charge density due to the PSSA dopant, which has a higher degree of deprotonation compared to DBSA (Table 3, entry 4).

A PANI-entangled oxidized CNTs (PANI@O-CNTs) membrane was also developed57. The PANI@O-CNTs membrane exhibited superior conductivity and stability due to in-situ polymerization of the PANI network on the CNTs framework. When an external voltage was supplied to this membrane, rejection rates for both the negatively charged methyl orange (MO) and positively charged methylene blue (MB) dyes increased dramatically (Table 3, entry 5). After 50 minutes of operation at a voltage of -2.0 V, the membrane’s rejection of MO increased from 35.2% to 77.4% and of MB from 41.5% to 79.8%. Combining electrostatic interactions with H₂O₂ oxidation led to higher rejection rates of 89.7% for MO and 93.4% for MB. Additionally, combining electrostatic interactions with H₂O₂ oxidation led to higher rejection rates of 89.7% for MO and 93.4% for MB.

The effect of oxygen plasma treatment was also investigated on PANI membranes made with carbon nanofibers (CNFs). Microfiltration PANI@O-CNF membranes were created by electrospinning PANI, followed by carbonization and oxygen plasma treatment64. The synthesis of PANI@O-CNF membranes improved the wettability and electrocatalytic reactivity for MB and acetaminophen (ACP) degradation (29.6 × 103 min-1 electrocatalytic constant for MB and 15.6 × 103 min-1 electrocatalytic constant for ACP) (Table 3, entry 6). Under combined microfiltration and electrocatalytic conditions, the removal efficiency of MB and acetaminophen reached 99% and 91%, respectively. Increased rejection after plasma treatment was due to strong electrostatic interactions between the negatively charged sites formed on the O-CNF membranes and the cationic MB dye molecules, while hydrophilic interactions with oxygen-containing functional groups on the membrane surface also contributed to increased ACP elimination.

The oxygen evolution potential (OEP) of pristine CNF membranes increased from 1.29 V to 1.62 V after 5–7 minutes of plasma treatment, which is related to improved electrocatalytic performance of the treated membrane. Recent work has developed a PPy@OCNT membrane by polymerizing PPy onto OCNT-modified PVDF substrate65. The developed membrane experienced an 82% drop in overall fouling resistance and a 95% decrease in irreversible fouling under applied potential, confirmed by electrically regulated hydraulic backwash. This improved the membrane permeance recovery rate from 39.6% without voltage to 99.1% at +1.19 V (Table 3, entry 7). A new approach to create conductive nanofiltration membranes achieved a 90% improvement in permeability, reaching 20.4 L/m²/h/bar, by combining interfacial polymerization with in-situ self-polymerization of EDOT (Table 3, Entry 8)66. Despite PEDTOT being a well-known conductive polymer, its poor solubility makes it challenging to use in membrane fabrication.

The semi-flexible π-conjugated backbone of PTI promotes polymer chain aggregation in solution, resulting in limited solubility, reduced mechanical flexibility, and challenging processing properties. In contrast, the EDOT monomer has good solubility properties. By combining interfacial polymerization with in situ self-polymerization of EDOT, the solubility issues of PEDOT can be solved, resulting in stable, highly conductive nanofiltration membranes. Using these PEDOT-doped membranes with an electro-assisted cleaning approach achieved quick flux recovery to 98.3% in just 5 minutes, significantly surpassing the standard 30-minute pure water cleaning. The anticipated electricity cost is only $0.055 per day.

A facile modulation of water transport through laminar Ti3C2Tx MXene membrane using an electric field was reported67 Fig. 5A (Table 3, entry 9). The permeability of water through a laminar MXene membrane has been significantly improved up to 70 times under a negative voltage of −5 V, while maintaining a 91% and 94% rejection for Cango Red and aniline, respectively. To prevent restacking of MXene nanosheets and improve water transport pathways. MXene@CNT nanofiltration membrane displayed 96% and 87% rejection for orange G and MO dyes under applied potential of 3 V (Table 3, entry 10)68. The enhanced water permeation and high dye rejection observed in MXene-based electro-responsive membranes result from field-induced expansion of interlayer spacing via electrostatic repulsion, suppression of nanosheet restacking by CNT spacers, and dynamic gating effects. Applied voltage modulates nanochannel architecture and surface potential, enabling increased water flux and selective ion/dye exclusion. These synergistic mechanisms establish MXene-based systems as capable runners for tunable, high-performance separation membranes. In another study, CNT-based ultrafiltration membranes were introduced using solid-state dry spinning of drawable CNTs onto carbon nanofiber (CNF) support membranes by varying the number of CNT layers (5, 10, 20, 30, 60) and the orientation angle of the CNT layers (0°, 45°, 90°)69. The achieved reaction kinetic constant for MB and ACP was 1.1 to 3.9 times higher than previously reported values, with a degradation efficiency of 99% for MB and ACP (Table 3, entry 11). The electrostatic interaction between the polar C–F bonds in PVDF chains and the mobile π-electron cloud of graphene promotes their self-assembly. This results in a strong β-phase, giving the composite film unique piezoelectric capabilities, enabling precise molecule separation. When a voltage is applied, the enlarged free volume fills the gaps between graphene and PVDF, forming nanochannels through which only particular molecules can travel. This mechanism reduces total permeability while boosting CO₂ selectivity (Table 3, Entry 13)70,71.

A Digital top-view image of a Ti3C2Tx membrane on supporting PVDF filter paper & Molecular model of Ti3C2Tx showing two layers of water with ions between the layers. Adapted with permission from ref. 72, Copyright (2018) American Chemical Society. B Reversible change of pore size between oxidation and reduction states of DBS-doped PPy membrane. Adapted with permission from ref. 75. Copyright (2011) American Chemical Society. C Water permeation for PPy-DBS membrane in the presence of applied voltage74 and D the electro-responsive gated mechanism based on a reversible wettability switch of the PFOS-doped. PPymembrane77. Permission to reprint granted.

Electro-responsive membranes with gated functionalities

The utilization of electrically responsive membranes for voltage-dependent exclusion mechanisms for ions and molecules has been proposed as an effective method to improve membrane selectivity, increase rejection efficiency, and enhance operational stability. Over the past few decades, various materials, including polymers, CNTs, MXenes, and viologen derivatives, have exhibited significant gating effects on molecules when subjected to an applied potential72. An electrically switchable membrane was developed by electrochemical polymerization of AOT-doped-PPy onto CNT-deposited PVDF support73.

The designed gated membrane can effectively eliminate organic micropollutants and metal ion contaminants from water by combining hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions. By providing a reversible electrical potential, trapped impurities can be released, allowing the membrane to regenerate and self-clean without the need for further chemicals (Table 4, Entry 1). The voltage-responsive gating behavior is caused by the reorientation of AOT molecules, which is influenced by the redox state of PPy under applied voltage. This transition impacts the solvent accessibility of the hydrophobic alkyl chains and negatively charged sulfonate groups of AOT, modulating the membrane’s surface charge and wettability, resulting in quick and effective single-pass separation of micropollutants and metals. This allows the hydrophobic alkyl chain and the negatively charged sulfonate group of AOT to switch positions, altering the membrane’s surface wettability and charge. As a result, efficient and rapid removal of micropollutants and metal ion contaminants from water is achieved through a single-pass filtration process. The membrane displayed switchable wettability change from superhydrophobic (145°) to superhydrophilic (13°) by oxidation (1.6 V) and reduction (−0.8 V), respectively. The AOT-PPY@CNT membrane effectively removed various organic contaminants with much lower energy consumption than a commercial nanofiltration membrane. Electrically-responsive PPY-DBS membrane with in-situ regulation of pore size can be tuned to alleviate fouling and enable selective separation74. Applying a negative voltage to PPy-DBS causes the retention of bulky DBS ions within the polymer structure, resulting in an accumulation of negative charges across the membrane.

External cations enter the PPy to compensate, increasing the distance between chains, leading to volume expansion and smaller pores. A positive potential causes cations to be expelled, resulting in volume shrinkage. Application of an oxidation potential of 0.7 V reduces the membrane’s pore size, whereas a reduction potential of −0.7 V enlarges the pore size (Table 4, entry 2) (Fig. 5B). The membrane’s specific flux in response to applied voltages was 21.9% higher than that without voltage. PPY-BDS membrane also displayed pulsatile drug release, highlighting the need for controlled and long-term drug release of protein therapeutics and the advantages of pulsatile drug delivery for specific medical conditions (Table 4, entry 3)75. Another research explored how applying various redox potentials (−0.9/0.6 V, −0.9/0.1 V, −0.6/0.1 V) to PPy-DBS surfaces in water enables controlled detention and release of DCM droplets, examining how these voltages influence droplet retention and release behavior76.

Results revealed that droplet release time depended on both the applied redox voltage and the thickness of the PPy-DBS layer. The quickest release occurred at −0.9/0.1 V, while increasing the coating thickness from 0.6 μm to 5.1 μm led to longer release times (Table 4, entry 4; Fig. 5C), which is due to slower desorption of DBS⁻ ions from the thicker PPy-DBS surface. The paper has not explored the capture and release of organic droplets in a systematic way, and there is room for further research on controlling the release process and understanding the effects of experimental parameters. The release time depends on the thickness of the PPy-DBS coating, which could be seen as a limitation in controlling the release time.

The longevity of the PPy-DBS surfaces is limited, as the surfaces eventually lose their ability to release the captured droplets after repeated redox cycles. Incorporation of PFOS⁻ ions into PPy micro/nanoporous film onto an anodic aluminum oxide (AAO) nanoporous membrane was demonstrated to create an electrically actuated nanochannel system for controlled, pulsatile release of drugs such as penicillin G sodium and Rhodamine B77 (Table 4, entry 5) (Fig. 5D). The maximum pore size that can be effectively gated may be limited, as the paper notes the gating ratio decreased with further increases in pore size beyond 59 nm. The drug release performance may be affected by the charge and properties of the drug molecules, as the paper found a slower release rate for the cationic Rhodamine B compared to the anionic penicillin G sodium.

Viologen derivatives, such as cucurbit[7]uril (CB[7]), were also used for molecular nanofiltration. The viologen enhances membrane conductivity and serves as an electric switch valve, while CB[7] stops viologen dimerization and enhances its oxidation-reduction stability56. The electric field increases repulsion between the membrane and dye, improving separation efficiency, especially for similar-sized molecules. Overall, this electrically-gated NF membrane demonstrates higher responsiveness and cycle stability compared to other advanced membranes (Table 4, entry 6).

Gated membranes based on carbon materials have recently gained significant interest for their exceptional ion-sieving capabilities. Notably, researchers have identified that precise ion sieving can be attained by deliberately manipulating the interlayer spacing of carbon-based materials. For example, CNT-based hollow-fiber membranes were used to construct a simple biomimetic membrane system that exhibits voltage-gated transport of nanoparticles across their pore channels78. Voltage-gated transport was attributed to the noncovalent interactions between the nanoparticles and the pore channels, which are controlled by the polarity of the CNTs. While working as a cathode, when voltage was applied to CNT membranes at various levels (0.4–0.6 V), membranes behaved positively or negatively, which in turn caused rejection or penetration of GNPs of different sizes (10 and 40 nm) (Table 4, entry 7). Switchable rejection rates of different ions and molecules through Ti3C2Tx MXene membranes were studied by applying positive (0.4 V) and negative (–0.6 V) potentials across the membrane72. MXene membranes as thin as 100 nm showed rejection rates above 97% for MB dye molecules, and the rejection can be further tuned by applying negative voltages (Table 4, entry 8). The voltage-gated rejection is attributed to the control of the MXene interlayer spacing, which expands under positive voltages and contracts under negative voltages, thereby affecting ion and molecule transport. Contraction and expansion with voltage are related to the movement of ions into and out of the MXene layers, which alter the electrostatic and steric interactions between the layers. Conductivity and voltage-gated ion transport behavior of MXene membranes were further improved by incorporating GO graphene oxide within MXene79. Applying a positive potential (+0.6 V) to MXene-GO enhances the electrostatic repulsion between the charged MXene-GO sheets and cations (Li+, Mg2+, or Al3+), promoting ion permeation. Applying a negative potential (-0.6 V) to MXene-GO boosts the electrostatic attraction, decreasing ion permeation (Table 4, entry 9).

Electro-responsive materials for membrane development and future directions

This section will compare different ERMs through various mechanisms, including electrostatic rejection, piezoelectric vibrations, and electrochemical reactions, which can be used to control porosity, wettability, surface charge and roughness, and catalytic efficiency for membrane water treatment applications.

Comparing the wetting characteristics of ERPs is essential for selecting the best one for membrane development. For instance, Au-coated perfluorooctanesulfonate (PFOS)-doped and de-doped PPy film displayed a superhydrophobic WCA of 152° and a superhydrophilic WCA of ~0°, respectively80. Tetrabutylammonium hexafluorophosphate (TBAFP)-doped PTI derivative, poly(G0 − 3 T COOR), transitioned from WCA of 154° upon doping to 15° after de-doping81. For PANI, the ITO-coated surface of the PFOS-doped PANI films (at 1.05 V) showed a WCA of 153° and ⁓0° after de-doping at −0.1 V82. LiClO4-doped-poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT) displayed reversible switching between superhydrophobic (162°) to superhydrophilic (0°) by doping and de-doping83.

Comparing the wettability of carbon-based materials, graphene can switch between hydrophobic and hydrophilic states under positive and negative electric fields, highlighting the significant influence of energy on material properties84. In contrast to carbon nanotubes (CNTs), which show minimal changes in WCA even at higher voltages, pure graphene exhibits a significant transformation, with its WCA decreasing from 117° to 86° as the voltage increases from 0 V to 40 V85. For applications that require enhanced hydrophilicity, graphene oxide (GO) proves to be an excellent choice. Notably, GO membranes can enable precise, reversible, and electrically tunable control of water permeation by forming conductive carbon filaments that generate local electric fields. These fields induce water ionization into H₃O⁺ and OH⁻, thereby modulating flux through GO capillaries without affecting membrane integrity. This introduces a new functional paradigm for electro-responsive membranes, allowing controllable water gating without relying on external mechanical changes or complex chemical modifications86. Additionally, MXenes, known for their exceptional 2D structure and high electrical conductivity, present exciting possibilities for electrochemical energy storage and catalysis87. However, challenges such as self-stacking and susceptibility to oxidation highlight the need for innovative synthesis methods. Developing environmentally friendly techniques for producing high-quality MXenes is essential to fully realize their potential in membrane applications and contribute to a sustainable future.

Altering anion dopants significantly impacts electrical conductivity and surface roughness. Naphthalene-sulfonic acid dopants improve film smoothness and polymer conductivity by reorganizing polymer chains. Benzenesulfonic compounds enhance charge delocalization and electronic conductivity through strong π-π interactions with the polymer chains, facilitating charge transfer88. The interaction improves charge delocalization in the polymer backbone, enhancing electronic conductivity through better charge transfer between chains. The presence of multiple -SO3- groups increases conductivity, while -OH groups improve interfacial adhesion through a chelating effect. Additionally, sulfonate groups enhance intermolecular interactions and increase the dopant’s solubility via hydrophilic interactions.

The stability of ERPs plays a crucial role in determining the electrocatalytic efficiency of responsive membranes. Conductive polymers high in nitrogen, such as PANI and PPy, have been demonstrated to significantly improve membrane electrocatalytic performance. Their aromatic frameworks and strategically positioned nitrogen atoms improve polymer stability and oxidation resistance. Furthermore, the conjugated polymer backbones promote efficient electron transport, allowing for cooperative interactions with iron-based catalytic species89.

Increased electrocatalytic performance is also related to the higher electronegativity of N atoms in the conjugated chains. This enhances the electron transfer capacity and increases the charge density of the positively charged carbon species, resulting in cleavage of the O–O bond. Conductivity is crucial for the electrocatalytic efficiency of ERPs, and based on the conductivity, PPy exhibits a higher conductivity of 105 S/cm, whereas PANI has considerably lower conductivity, which in turn lowers its catalytic efficiency90. However, the conductivity of polymers can be enhanced through various methods, such as modifying their doping ions and levels, treating them with solvents, and adding conductive additives.

In conclusion, the application of electric fields enables the controlled release of substances from responsive membranes. However, the current challenge lies in the limited availability of easily integrable ERPs and 2D materials that are readily compatible with standard composite membrane fabrication methods. For example, it is essential to improve the electrical efficiency and cathodic electrochemical stability of the membrane while simultaneously reducing the overall costs of the device. This involves controlling the membrane pore structure to achieve strong electrostatic interactions that support high ion rejection. At higher ion concentrations, the electrical enhancement of ion rejection can weaken, necessitating the application of higher external voltages to address this issue. Enhanced precision control and tuning of the membrane’s structure to balance ion rejection and water permeance are also required. This would improve membranes’ controllability, reproducibility, and scalability based on 2D materials. Another major issue is to investigate the use of oxygen plasma-treated cellulose nanofiber (CNF) membranes in electrocatalytic membrane reactors (ECMRs), focusing on their stability and self-cleaning capabilities. Additionally, it is crucial to research how pollutants are removed and how these removal processes respond to changes in electric field intensity. We should also explore how the positioning of the membrane module within the system affects the strength of the electric field.

In summary, the application of electric fields enables the controlled release of substances from electrically responsive membrane matrices. Despite this potential, challenges remain, particularly the limited availability of ERPs and two-dimensional materials that are readily compatible with standard composite membrane fabrication methods. Moreover, the use of external electric fields can increase energy demands and operational expenses. Nevertheless, there is considerable scope for advancing the large-scale manufacturing and real-world application of electrically responsive, smart membranes with antifouling and self-cleaning capabilities.

Cost comparison analysis shows that alternative electro-responsive polymer membranes provide substantial cost advantages over traditional Nafion membranes, with alternatives costing as little as $9–47 per square meter compared to Nafion’s $700–2229 per square meter. Electro-responsive polymer membranes used in fuel cells, redox flow batteries, water treatment, and related fields exhibit significant cost differences compared to conventional perfluorinated membranes. In several studies, Nafion is reported to cost between USD 700 and 2229 per square meter. In contrast, alternative membranes—such as biochar-doped sulfonated polyether sulfone, Nafion-cellulose composites, and 3D-printed sulfonated polyether ether ketone—are described as 5–30 times less expensive, with some alternatives costing as little as USD 9–47 per square meter.

Other reports note that operational cost elements such as energy consumption and membrane replacement can represent significant cost drivers. For example, one study indicates an energy use of 0.324 kWh per kilogram in electrodeionization, while a separate investigation estimates an anion exchange membrane for carbon dioxide electrolysis at 796 euros per ton of CO produced. Polymer alternatives in redox flow batteries also achieve 99.9% capacity retention and, in one case, a 57.7% material cost reduction relative to Nafion. These findings collectively support the conclusion that, in select application areas, alternative electro-responsive membranes deliver substantial capital and performance-related cost advantages compared with traditional options.

pH-responsive materials (PRMs)

pH-responsive materials have attracted substantial attention owing to their exceptional properties to exhibit sharp and reversible changes in response to variations in external pH levels. PRMs, especially pH-responsive polymers (PRPs), demonstrate responsiveness to variations in environmental pH through modifications in their structural and property characteristics, including conformational, structural, and solubility changes. PRPs are characterized by the presence of acidic or basic functional groups that can either accept or donate protons upon external pH variations17,91,92,93. This capability renders them highly suitable for membrane functionalization, exhibiting controlled separation performance. This section will examine the chemistry and pH-dependent characteristics of PRPs in the context of their application in membrane development, alongside future opportunities for enhancement.

pH-responsive polymers

PRPs generally utilized in membrane development are typically classified into two major types: polyacidic (polyanionic) and polybasic (polycatonic) PRPs. Polyanions feature ionizable acidic side groups along their polymer chains. In contrast, polycations include basic groups like amine (NH₂), which can be integrated into the backbone or attached as side groups. The extent of ionization depends on the pH of the environment. In contrast, polycations include basic functionalities, such as amine (NH₂) groups, which can be incorporated into the main chain or attached as side groups. The degree of ionization of these functional groups varies with the environmental pH, leading to structural changes in the polyelectrolyte94. A polyacid tends to adopt a more extended conformation when the surrounding pH is greater than its pKa. Conversely, the polymer chains collapse when the pH is lower than the pKa. For a polybase, the situation is different: at pH values greater than its pKb, the polymer chains also collapse, while they expand when the pH is lower than the pKb. Figure S5 presents a schematic of how the ionization level of the ionic chain groups determines the states of polyacids and polybases. However, a detailed description of their individual chemistry and pH-responsive behavior mechanisms is given in the supporting information. These materials exhibit a well-known behavior: the swelling and deswelling of polymers based on their ionizable groups. Ionization makes these polymers water soluble when ionized, but they lose solubility in their neutral form. This shift is caused by a decrease in electrostatic repulsion as the ionizable groups neutralize, allowing hydrophobic interactions to dominate. The charge state, and thus solubility, can be reversibly altered by adjusting the pH of the surroundings94.

pH-responsive enabled membranes

The pH-responsive membrane is made by integrating pH-responsive polymers into its structure. These membranes feature polyelectrolytes with ionizable acid or basic groups that can reversibly gain or lose protons depending on the surrounding pH. These changes lead to conformational adjustments in the membrane, causing the polymer chains to collapse or extend, which, in turn, alters the membrane’s surface properties and channel size95. This section will explore recent advancements in pH-responsive smart membranes, focusing on dynamic pore size variation in response to pH, wettability, and stability of membranes over different pH ranges. Table 5 highlights recent research progress, although many challenges remain.

Polystyrene-b-poly(4-vinylpyridine) (PS-b-P4VP)-based pH selective membranes possess the unique capability of adjusting their pore sizes in direct response to fluctuations in pH levels96. This membrane reveals a tightly sealed pore configuration at lower pH levels, functioning with a permeance of roughly 10 L/m²/h/bar. In this acidic environment, the P4VP blocks lining the pore walls undergo protonation, triggering them to extend outward to negligible repulsion of charge, thereby effectively closing the pores. In contrast, under more alkaline conditions, P4VP chains are collapsed, which causes opening of PS-b-P4VP membrane pores, leading to a significant rise in permeance to over 800 L/m²/h/bar. This unique responsiveness to pH changes indicates the dynamic functionality of the membrane (Table 5, entry 1).

A group of researchers developed carbon nanotubes (CNTs) embedded with polyacrylic acid (PAA) intercalated between reduced graphene oxide (rGO), which enhances pH responsiveness and creates an additional pathway for water transport97. In neutral and alkaline environment, the interaction between PAA and rGO improves separation efficiency, with a phosphate retention rate of 92.7% for 20 mg/L/bar (Table 5, entry 2) (Fig. 6A). The study also tested polyethylene glycol (PEG) 800 across various pH levels, finding that the membrane’s water permeability and phosphate rejection remained stable after five cycles from pH 3.0 to 8.2, confirming the durability and reversibility of its pH response. However, the lack of performance data under strongly alkaline conditions suggests a limited practical application due to the narrow pH response range.

A pH-responsive property of the RGO-gCNT membrane. Adapted with permission from ref. 97. Copyrights (2019) Separation and Purification Technology. B pH-responsive ALG-modified membrane. Adapted with permission from ref. 98. Copyrights (2019) American Chemical Society. C pH-responsive nanochannels of GO and GO-PEI membranes. Adapted with permission from ref. 100. Copyrights (2021) American Chemical Society. D Schematic illustration of the pH-responsive performance of WSe2/PAA nano-gated membrane. Adapted with permission from ref. 101. Copyrights (2022) Chemical Engineering Journal. E Schematic illustration of pH-responsive GO/Gel membranes. Adapted with permission from ref. 102. Copyrights (2019) Journal of Membrane Science. Permission to reprint granted.

Using NIP technology, an NF membrane based on a five-block copolymer was developed with a pore size of 0.9 nm. Unlike the earlier example of carbon nanotubes (CNTs) grafted with poly(acrylic acid) (PAA), this copolymer’s pH-responsive conformational changes do not alter the retention of PEG 1000 or the membrane pore size (Table 5, entry 3) (Fig. 6B)98.

This constancy was attributed to the high grafting density of the copolymer chains, which restricts the spacing between them. At 0.1 M ionic strength, the stability of water flux demonstrated that salt ions did not induce chain rearrangement. This reliable performance is particularly advantageous for size-based separations. Furthermore, the membrane exhibited a molecular weight cut-off (MWCO) of ~1 kDa, yet its permeability (13.0 ± 0.63–15.9 ± 0.06 L/m2 h bar) exceeds that of commercial membranes with a MWCO of 1 kDa (15.4 L/m2 h bar) and even surpasses that of some rated at 2 kDa99. This advanced technology establishes a distinct cutoff value for molecular weight in nanofiltration membranes. If the pH response range (from pH 4–8.5) can be further refined, the application scope of these NF membranes will be significantly enhanced.

To tackle the balance between permeability and selectivity, positively charged PEI was grafted onto negatively charged GO nanosheets. This strategy mirrors the operational mechanism of glomeruli, which employs both molecular size screening and charge selectivity100. The incorporation of the GO-PEI component significantly enhanced the hydrophilicity and surface charge of the membrane. Furthermore, this modification facilitated an increase in the size of the nano-channels due to the conformational changes induced by the PEI. Consequently, the pure water flux achieved a rate of 88.57 L/m2/h/bar, which is approximately four times higher than that of traditional GO membranes (Table 5, entry 4) (Fig. 6C). Membrane displayed pH-dependent rejection of Methylene blue (MB) and methyl orange (MO), at pH 12 and pH 2 levels, respectively, with a removal rate reaching as high as 96%.