Abstract

The diminution of the benefits of domestic pollution control by greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions has received considerable attention. Emission factors related to the construction and operation of wastewater treatment systems have been well characterized in urban settings but far less so in rural areas. To address this gap, we developed an integrative modeling framework that quantifies the entire chain of rural domestic pollution processes together with the associated GHG emissions. Our analysis suggests that the control of China’s rural domestic pollution has realized a threefold increase over the past decade, resulting in a decline of carbon (C), nitrogen (N), and phosphorus (P) discharge to surface waters by 1158 Gg, 316 Gg, and 43 Gg, respectively. However, GHG emissions have also discernibly increased from 26.7 Tg to 31.4 Tg. Even though over 70% of China’s rural domestic pollution is still being discharged untreated, GHG emissions from wastewater treatment systems have become prevalent and currently account for more than 60% of total GHG emissions from rural areas. Considering the on-going construction of numerous new wastewater treatment systems in rural areas, enhancing wastewater treatment capacity, strengthening resource recovery, optimizing dietary patterns of the public, and promoting the use of clean energy are recommended to balance the trade-offs between environmental pollution abatement and climate change mitigation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The global aspiration for sustainable socioeconomic development requires addressing the pressing challenges of environmental pollution and climate change1,2. Currently, forty-three percent (43%) of the world’s population resides in rural areas, generating substantial domestic pollution (https://data.worldbank.org.cn/). The wastewater treatment capacity in rural areas arguably remains modest and differs both functionally and structurally from the centralized systems in urban settings, resulting in a more diverse array of greenhouse gas emission pathways and domestic pollution disposal3,4,5. Treated domestic pollution is discharged into water bodies as tailwater, after releasing large amounts of greenhouse gases during the treatment process6,7. The remaining by-products of domestic pollution are either directly discharged into receiving water bodies or recycled into the environment as fertilizer1,8,9,10. Both pathways contribute to environmental pollution and GHG emissions11. The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals state that by 2030, agricultural productivity will be doubled, along with the income of small-scale food producers, especially women, indigenous peoples, farming families, pastoralists, and fishers (https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/). The on-going socio-economic development in rural areas will increase the capacity for domestic pollution treatment, but with the caveat that will be accompanied by an increase in GHG emissions12,13,14. GHG emissions from the disposal of rural domestic pollution have long been neglected due to the relatively low wastewater treatment rates compared with urban areas15,16,17,18,19. This issue is even more pronounced in China, where the rural population accounts for 34.8% of the country’s total population and 14.3% of the global rural population as of 2022 (China Statistical Yearbook, https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/ndsj/2023/indexch.htm). According to UN-Water, China’s domestic pollution treatment rate is 62%, with the rate in rural areas being one-third of that in urban systems (https://www.sdg6data.org/zh-hans/indicator/6.3.1). To address this profound disparity, China has proposed the rural domestic wastewater treatment rate to reach 40% by 2025, which signifies the need to characterize the tradeoffs between the mitigation of domestic pollution and potential exacerbation of GHG emissions. It is thus an emerging imperative to establish robust relationships among domestic pollution rates, wastewater treatment capacity, and GHG emissions in rural environments7,20,21.

Domestic pollution rates are typically estimated by indirect calculations of food intake and detergent use10,22,23,24. Food intake can be determined from food consumption data in areas with detailed statistics23,25, and then the estimated per capita load is multiplied by the population size to quantify the total impact. Detergent use is estimated either by a fixed load per capita or by taking economic levels into account, with additional adjustments for phosphorus-free detergents26,27. Generally, a multitude of input-output assumptions have been used to assess the flow of carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus, via food production, food intake, pollution reduction, tailwater discharge, soil retention, and pollution volatilization23,28,29,30,31. In the same vein, the calculations of GHG emissions have been predominantly based on empirically derived emission factors of various wastewater treatment processes32,33,34. The GHG emission factors for biochemical processes in wastewater treatment plants are studied at national, provincial, and plant levels32,35. GHG emissions from urban wastewater treatment systems have been evaluated at the national level, providing evidence that wastewater treatment can be a significant source of GHG emissions5,16,18,34. Although the domestic pollution cycle and accompanying GHG emission rates have been assessed independently, their collective impact and joint consideration in mass balance exercises has yet to be examined. Additionally, current research has mainly focused on urban areas, while rural regions have received considerably less attention. China is a case in point, where wastewater treatment data mainly rely on first and second pollution censuses, which do not account for 8,855 wastewater treatment facilities with a capacity of less than 500 m³/d18,32,36,37,38. Considering that most of these small treatment facilities are located in rural areas, there is a major knowledge gap in understanding the pertinent domestic pollution cycles and GHG emissions.

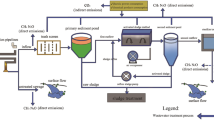

To advance our understanding of the broader implications and tradeoffs from the operation of wastewater treatment plants, the present study introduces a modeling framework that jointly considers the domestic pollution cycle and GHG emissions (Fig. 1a; Supplementary Note 1). We also introduce a composite trade-off index to evaluate the relationship among the magnitude of domestic pollution, treatment and discharge rates, and GHG emission fluxes. Extending previous studies, our work is designed to accommodate the interconnected dynamics of domestic pollution cycles and GHG emissions, and is thus conducive to assessing the associated co-benefits and tradeoffs4,7,27,39,40. Our key objectives are to: (i) quantify the domestic pollution cycle processes and the corresponding GHG emissions in rural China over the past decade, covering the entire chain of rural domestic pollution output, reduction, discharge, and GHG emission rates; (ii) assess the co-benefits and tradeoffs by examining the key influential factors; and (iii) design various scenarios to analyze the impact of dietary patterns, demographic trends, and wastewater treatment rates on the severity of environment pollution and GHG emissions. Our findings suggest that increased wastewater treatment rates will accelerate GHG emissions in rural China but could also amplify the co-benefits owing to pollution mitigation and improved GHG emission intensity. We conclude by advocating increased wastewater treatment rates, embracement of clean energy, healthier dietary habits, and consideration of a wider array of resource recovery technologies to improve the environment and reduce GHG emissions in rural China.

Results

Fate of rural domestic pollution cycles and associated GHG emissions

Rural domestic C, N, and P pollution, along with GHG emission rates in China, were closely interconnected and exhibited significant interannual variability (Figs. 1; S2-S36). Over the past decade, the rural population in China represented an average of 560 ± 0.48 million people, with annual consumption of 207.1 ± 9.6 Tg of food and 4.23 ± 0.34 Tg of detergents. Excluding human intake and metabolism, the estimated fluxes of C, N, and P pollutants were 5244 ± 444 Gg, 2396 ± 125 Gg, and 671 ± 44 Gg, respectively. These pollution fluxes are managed through three methods: treatment by wastewater treatment systems (treatment-related), direct discharge into water bodies as nonpoint source pollution (untreated), and recycling back into the environment as organic fertilizer (recycled). Consequently, a total of 29,090 ± 2389 Gg CO2-eq of GHGs were collectively emitted through these processes, while the per capita GHG emissions were approximately equal to 52.6 ± 8.6 kg CO2-eq. Simply put, we can infer that for each kilogram of domestic pollution treated, 0.14 ± 0.02 kg CO2-eq of GHGs are released (Fig. 1a).

We next examined the coupling between pollution processes and GHG emission rates (Fig. 1b–e). For treatment-related pollution, pollutants are first collected by sewers, resulting in the release of nitrous oxide, methane, and carbon dioxide owing to the prevailing anaerobic conditions. The sewers emitted 48.1 ± 14.3 Gg of C and 0.11 ± 0.03 Gg of N into the atmosphere along with GHG emissions of 1084 ± 322 Gg CO2-eq. Pollutants carried within the sewers are ultimately transported to the wastewater treatment plants for processing, where the corresponding C, N, and P fluxes were 937 ± 296 Gg, 334 ± 120 Gg, and 120 ± 41 Gg. Sewage treatment and subsequent pollutant reduction comprising a multitude of steps such as construction of wastewater treatment systems, material usage, sewer operation, biological processes, sludge disposal, and electricity consumption, collectively produced significant GHG emissions amounting to 14,937 ± 4,218 Gg CO2-eq. Of the reduced pollutants, 613 ± 182 Gg of C and 282 ± 102 Gg of N were emitted into the atmosphere, while the remainder accumulated in the sludge. The sludge is generally disposed of through sanitary landfill, composting, incineration, and other methods. Sanitary landfill and composting of sludge discharged pollutants into groundwater through the leaching process, with values of 7.62 ± 1.82 Gg of C, 2.19 ± 0.52 Gg of N, and 0.63 ± 0.15 Gg of P.

Composting of sludge also discharged pollutants to surface water through runoff scouring, with amounts of C, N, and P at 0.33 ± 0.24 Gg, 0.07 ± 0.05 Gg, and 0.08 ± 0.06 Gg, respectively. The composting process released small amounts of pollutants into the atmosphere together with soil respiration, with values of 10.4 ± 7.9 Gg of C and 0.0006 ± 0.0005 Gg of N. The net accumulation of C, N, and P in sludge was 132 ± 31 Gg of C, 21.8 ± 4.9 Gg of N, and 119.7 ± 43.8 Gg of P, displaying considerable variability depending on the sludge yield and treatment method. Finally, the tailwater contributed 89.5 ± 20.9 Gg of C, 123.1 ± 33.2 Gg of N, and 4.5 ± 0.7 Gg of P to surface water, triggering GHG emissions of 477 ± 120 Gg CO2-eq due to the increased water pollution loading.

Untreated pollution directly contributed 3217 ± 422 Gg of C, 1254 ± 133 Gg of N, and 141 ± 13 Gg of P to surface waters, resulting in an additional 10,333 ± 1,287 Gg CO2-eq of GHG emissions. In contrast, treated pollution leads to a reduction in direct wastewater discharges, and consequently reduction in GHG emissions from the receiving water bodies. Thus, the indirect GHG reduction was 5,655 ± 1,914 Gg CO2-eq, accounting for approximately 39% of the GHG emissions from wastewater treatment processes. Concerning the third disposal method, recycled pollution as fertilizers contained 952 ± 330 Gg of C, 685 ± 127 Gg of N, and 405 ± 71 Gg of P. The recycled pollutants exported 19.6 ± 6.5 Gg of C, 17.8 ± 3.2 Gg of N, and 5.7 ± 0.9 Gg of P into surface water via runoff washout, and leached 47.7 ± 15.9 Gg of C, 61.8 ± 11.1 Gg of N, and 4.5 ± 0.7 Gg of P into groundwater. Additionally, 0.11 ± 0.04 Gg of C, 238 ± 82 Gg of C, 103 ± 19 Gg of N, 157 ± 29 Gg of N, and 8.9 ± 1.7 Gg of N were emitted through soil respiration in the form of methane, carbon dioxide, nitrogen, ammonia, and nitrous oxide, respectively, collectively resulting in GHG emissions of 3,820 ± 715 Gg CO2-eq.

In summary, wastewater treatment systems in rural China reduced C fluxes by 18% over the past decade, with 59%, 15%, 25%, and 1% of the C output transported to surface water, soil, atmosphere, and groundwater, respectively. For N, the corresponding percentages were 14%, 58%, 15%, 24%, and 3%, respectively, whereas the same pathways for P were 18%, 23%, 77%, <1%, and 1%. GHG emissions from wastewater treatment, untreated pollution discharges, and recycled pollution processes accounted for 51%, 36%, and 13%, respectively. Our results showed that wastewater treatment systems contributed up to 51% of total GHG emissions, even though the pollutants were reduced by only 18%. It is expected that more GHGs will be released as rural wastewater treatment rates increase in the future.

Rural domestic pollution and requirements for increased treatment capacity in China

China’s rural domestic pollution exerts severe environmental stress, and thus, the pressure to augment the wastewater treatment capacity increases with the ever-growing population demands. By 2022, China had a rural population of nearly 500 million, accounting for approximately 15% of the global rural population. Notwithstanding the decrease in China’s rural population by 22% due to urbanization (Figures S2-S15), per capita domestic water consumption, food consumption, and detergent use increased by 1.2 times, 1.1 times, and 1.7 times, respectively, reflecting the broader societal economic improvement. Considering the combined effects of a declining rural population and increased per capita consumption, the net food and non-food consumption of C, N, and P decreased from 51.6, 2.74, and 0.79 Tg in 2013 to 39.9, 2.37, and 0.65 Tg in 2022, respectively (Fig. 2a). After accounting for losses associated with absorption and respiratory releases by the human body, the C, N, and P fluxes declined from 6.26, 2.67, and 0.78 Tg in 2013 to 4.86, 2.32, and 0.63 Tg in 2022. Over the last 10 years, the per capita C, N, and P outputs were on average 9.37 ± 0.53, 4.29 ± 0.29, and 1.20 ± 0.06 kg, respectively. The rate of access to sanitary toilets in China’s rural areas increased from 74% in 2013 to 89% in 2022, effectively enhancing the capacity for domestic pollution collection. Yet, while the rural domestic wastewater treatment rate rose from just over 9% in 2013 to 31% in 2022, the untreated domestic pollution still remains predominant. The relatively low wastewater treatment rate introduced significant pressure on the water resources, with nearly 55% of C and N flowing into the surface waters in 2022.

China’s rural C, N, and P pollution abatement by wastewater treatment systems increased from 506, 158, and 59 Gg in 2013 to 1366, 513, and 181 Gg in 2022, respectively (Fig. 2a). Likewise, per capita reductions increased from 0.81 kg of C, 0.25 kg of N, and 0.09 kg of P in 2013 to 2.80 kg of C, 1.05 kg of N, and 0.37 kg of P in 2022 (Figs. S2-S15). The proportion of reduced C, N, and P pollution to total outputs increased from 8.1%, 5.9%, and 7.6% in 2013 to 28.1%, 22.1%, and 28.6% in 2022, respectively. It is important to note though that the reduced pollution due to the operation of wastewater treatment plants does not vanish, with approximately 66% of C and 84% of N of the treated material being biochemically emitted to the atmosphere, while the remainder accumulates in the sludge (Fig. 2b). Pollutants from sludge discharged into water bodies through leaching or runoff are accounted for to the contribution of sludge yield and rainfall. Sewerage, tailwater, and sludge leaching had a relatively modest impact on the pollution cycles over the past decade. C, N, and P discharged by these processes accounted for ~3%, 5%, and 1% of total domestic pollutant outputs, respectively (Fig. 1). Untreated pollution decreased from 4049 Gg of C, 1502 Gg of N, and 167 Gg of P in 2013 to 2776 Gg of C, 1100 Gg of N, and 126 Gg of P in 2022, reflecting the decrease in rural population and increase in the wastewater treatment rate (Fig. 2a). Recycled pollution declined from 1614 Gg of C, 952 Gg of N, and 543 Gg of P in 2013 to 533 Gg of C, 540 Gg of N, and 321 Gg of P in 2022, driven by population reduction and promotion of sanitary toilets (Fig. 2c). Specifically, the increased rate of access to sanitary toilets increased the amount of directly disposed pollutants rather than recycled. Recycled pollution is often used as fertilizer, and the pollutants are released through soil respiration, leaching, and runoff washout, while the remainder accumulated in the soil. The processes associated with recycled pollution displayed a decreasing trend over the last ten years.

The final destination of pollution depending on the disposal methods considered could be surface water, groundwater, soil, and atmosphere (Figs. 1, 2). Pollution discharged into surface water decreased from 3881 Gg of C, 1593 Gg of N, and 179 Gg of P in 2013 to 2723 Gg of C, 1277 Gg of N, and 135 Gg of P in 2022. Pollution accumulated in the soil decreased from 1197 Gg of C, 484 Gg of N, and 588 Gg of P in 2013 to 465 Gg of C, 288 Gg of N, and 494 Gg of P in 2022. The proportion of C and N accumulated in the soil to total pollution outputs decreased from 19.1% and 18.0%, respectively, to 9.6% and 12.4%. C and N removal processes release nitrogen, methane, carbon dioxide, and other gases to the atmosphere, whereas P displays elevated accumulation in the soil as sludge. Therefore, P accumulated in the soil accounted for more than 75% of the total P export. Pollution leached into the groundwater decreased from 85.4 Gg of C, 86.6 Gg of N, and 6.4 Gg of P in 2013 to 31.6 Gg of C, 47.9 Gg of N, and 3.8 Gg of P in 2022.

Pollution emitted into the atmosphere increased from 1091 Gg of C and 523 Gg of N in 2013 to 1642 Gg of C and 710 Gg of N in 2022. The fraction of C and N emitted into the atmosphere accounted for 13.2% and 19.2% of the total C and N discharges, respectively, and increased to approximately 30% in 2022. The increase in atmospheric pollution is closely associated with the discernible rise in gaseous emissions from the wastewater treatment process.

The present analysis showed that wastewater treatment not only alters the processes involved in the pollution cycle but also directly affects GHG emissions. In terms of the pollution treatment process, the higher the pollution reduction rate, the greater the amounts of pollutants discharged into the adjacent media (soil, water, and air) from the associated sewer network, sludge, and tailwater. Conversely, pollutants discharged from untreated and recycled sources decreased, as higher pollutant collection rates lead to a reduction in recycled pollution, thereby decreasing leaching into groundwater. Furthermore, the increased tailwaters stemming from the increased wastewater treatment rates contributed to a rise in pollutants emitted into the atmosphere. Dynamic changes across provinces as well as regional differences reinforce this perspective (Figs. S2-S15). Nevertheless, the proportion of untreated pollution discharged directly into the environment by 2022 still exceeds 70%, emphasizing the urgent need to upgrade wastewater treatment capacity.

Leading role of rural wastewater treatment systems in GHG emissions

Total GHG emissions from rural domestic pollution in China increased from 26.7 Tg in 2013 to 31.4 Tg in 2022 (Fig. 3a). Methane emissions decreased from 399 Gg to 337 Gg, nitrous oxide fluctuated around an average level of 33 Gg, and carbon dioxide emissions increased from 5972 Gg to 12,457 Gg. With a 13-23% reduction in domestic pollution, improvements in wastewater treatment capacity have led to a discernible increase in GHG emissions. The proportions of methane, nitrous oxide, and carbon dioxide emissions to total GHG emissions shifted from 41.8%, 35.8%, and 22.3% in 2013 to 30.0%, 30.4%, and 39.6% in 2022, respectively. The increase in carbon dioxide emissions was primarily driven by higher consumption of electricity and materials used for the construction of wastewater treatment plants. Likewise, changes in methane and nitrous oxide emissions were associated with shifts in rural domestic pollution disposal methods. Specifically, analysis of GHG emissions from three disposal methods revealed that emissions from both treatment-related and untreated pollution accounted for more than 80% of total GHG emissions. After 2016, GHG emissions from wastewater treatment systems became dominant, exceeding 50% of total GHG emissions, a proportion that increased to 60% in 2022. The share of GHGs emitted from recycled pollution was the lowest, decreasing from 20% in 2013 to less than 10% in 2022, due to efforts to promote sanitary toilets. Thus, the increase in rural wastewater treatment capacity not only significantly raised GHG emissions but also altered the composition of GHGs, alongside the amelioration of environmental pollution (Fig. 3a−d).

a National trends of total GHG emissions over time; b Provincial trends of total GHG emissions over time; c GHG emissions from the various processes in wastewater treatment systems in China; d GHGT differences (10-year average values) across Chinese provinces and cities; e National trends of GHGT and GHGR emission intensity over time.

We next analyzed GHG emissions from wastewater treatment systems (Fig. 3c). All individual wastewater treatment processes exhibited an increasing trend, with peaks observed in 2016 and 2020. The 2016 peak in GHG emissions was driven by a rapid increase in the wastewater treatment rate, which rose from 11.4% in 2015 to 20% in 2016. This increase resulted in higher GHG emissions from electricity consumption, material usage, biochemical processes, and tailwater discharge. In terms of GHG emissions from the operation of wastewater treatment systems, the contributions over the last decade, in descending order, were as follows: material usage (26.7%), electricity consumption (25.1%), sludge disposal (20.7%), biochemical processes (13.2%), sewerage (9.7%), and tailwater (4.5%). The 2020 peak was primarily due to the construction of new wastewater treatment systems. The share of GHG emissions from construction decreased from 30.9% in 2010 to 16.1% in 2022. Furthermore, we quantified GHG emissions through two pathways. The first pathway refers to direct GHG emissions from wastewater collection and treatment, while the second pathway includes indirect GHG emissions from electricity generation, construction, and material use. The results showed that indirect GHG emissions exceeded direct emissions (Fig. 3e). In 2013, the direct and indirect GHG emissions were 2.8 Tg and 5.8 Tg, respectively. By 2022, these values had increased to 8.5 Tg and 11.0 Tg. Although the share of direct GHG emissions from rural wastewater treatment in China rose from 33% to 43% over the past decade, GHG emissions from construction are expected to continue rising, given China’s aspirations to improve rural wastewater treatment. This again highlights the new emerging issue of GHG emissions related to rural domestic wastewater treatment systems.

Total GHG emissions (GHGT) per capita approximately displayed 1.5 times increase from 42.6 kg CO2 eq to 64.3 kg CO2 eq over the past 10 years (Fig. 3e). GHG emissions from wastewater treatment systems (GHGR) per capita rose nearly tripled, rising from 13.6 kg CO2 eq to 39.8 kg CO2 eq. The increase in per capita GHG emission intensity reinforces the point that wastewater treatment significantly contributes to the rise in GHG emissions. In contrast, GHGR per unit of treated wastewater decreased by about 20% from 1.43 kg CO2 eq per m³ to 1.11 kg CO2 eq per m³, which is attributed to the gradual expansion of wastewater treatment systems. Simply put, once they are built, these treatment systems reduce the need for additional infrastructure in subsequent years, thereby leading to a decrease in GHG emissions. Further, we analyzed GHG emissions from the perspective of pollutant reduction. The average GHGR per unit of C, N, and P removed were 16.2 kg CO₂-eq per kg C removed, 46.5 kg CO₂-eq per kg N removed, and 127 kg CO₂-eq per kg P removed, respectively. Similar to GHGR per unit of treated wastewater, emission intensities in 2022 were 15.8%, 30.0%, and 25.8% lower than those in 2013. We also examined the trends of GHGT per unit of C, N, and P output, which suggested that the average emission intensities were 5.61 kg CO₂-eq per kg C output, 12.2 kg CO₂-eq per kg N output, and 43.7 kg CO₂-eq per kg P output, respectively. The emission intensity in 2022 increased by nearly 1.5 times compared with 2013, due to a decrease in rural population and changes in dietary habits and detergent use. GHGT per unit of pollution output is lower than GHGR per unit of pollution removed, suggesting that the wastewater treatment process inevitably releases more GHGs per capita.

To recap, the present analysis showed that the increased wastewater treatment rate significantly increased GHG emissions during the pollution-reduction processes and gradually became the dominant source of emissions. It is thus expected that GHG emissions will rise rapidly with the improvement of wastewater treatment capacity. Wastewater treatment rate, population size, food intake, and non-food use were the primary influencing factors for both GHG emissions and pollution reduction, and the differentiated GHG emissions by province further support this view (Figs. S16-S36). For example, in five provinces with average wastewater treatment rates exceeding 40% over the past ten years (Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin, Zhejiang, and Jiangsu), GHG emissions from wastewater treatment systems accounted for more than 69% of total GHG emissions in those provinces or cities. By 2022, this share had risen to over 77%. Likewise, while provinces with high wastewater treatment rates, such as Shanghai, Tianjin, and Beijing, contributed a low percentage of national GHG emissions, provinces with both high rural populations and wastewater treatment rates, such as Zhejiang and Jiangsu, accounted for a large share of national GHG emissions. In the same vein, although the populations in Zhejiang and Guizhou were similar, the dietary intake of C, N, and P in Zhejiang was approximately 1.5 times greater than that in Guizhou and so was their corresponding pollution footprint.

Co-benefits and trade-offs between pollution reduction and GHG emissions

Considering that lower values are suggestive of higher co-benefits, our results showed that the composite trade-off index in rural China decreased from 1.1 in 2013 to 0.3 in 2022 (Fig. 4a, b). The GHG emissions index increased by 40%, while the environment index decreased by 75%, and the population index decreased by 22% during the same period. Overall, the positive outlook from the treatment of rural domestic pollution mainly stemmed from the decline in China’s rural population that moderated the increase in GHG emissions. Similarly, the composite trade-off index decreased across provinces by rates ranging from 63% to 97%, and the trends in the GHG emissions, environment, and population indices were consistent with those observed at the national level.

a National trends of the wastewater treatment rate, population size, food and non-food intake, access rate to sanitary toilets, and GHGT per kg intake treated over time; b National trends of the composite tradeoff index over time; c Trends of the composite tradeoff index across the Chinese provinces and cities; d Log-Mean Divisia Index (LMDI) analysis; e Geodetector analysis; f Scenario analysis (A–F represent healthy diets, 45% wastewater treatment rate, 80% wastewater treatment rate, electricity reduction, rural population decline, and combined strategies, respectively).

Interestingly, the composite trade-off index for Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai, and Zhejiang was on average lower than the values registered in other regions over the past decade (Fig. 4c). Jiangsu had a similar wastewater treatment rate to Beijing and Tianjin, but the composite trade-off index was significantly higher (≈ 0.5), due to a larger rural population and thus higher production of untreated pollution. The composite trade-off index was worse in Heilongjiang and Henan. Heilongjiang displayed the lowest wastewater treatment rate, which was lower than 1% before 2015. In contrast, although the average wastewater treatment rate in Henan was ≈20%, close to the national average, the larger rural population led to a reduction of the co-benefits. This is also a plausible explanation of the higher composite trade-off index in several other provinces with relatively lower wastewater treatment rates, including Qinghai and Gansu, compared to Henan. By 2022, the composite trade-off index remained better in Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai, and Zhejiang, which had high wastewater treatment rates and relatively low rural population sizes (Figs. S37-S40). Provinces with lower wastewater treatment rates and larger rural population sizes, including Anhui, Jiangxi, Shandong, Henan, Hunan, Guangxi, and Guizhou, should receive more attention in the future.

The results of the LMDI suggest that GHGR increased by 1.10 Tg over the past ten years (Fig. 4d). The wastewater treatment rate and GDP per capita were the primary factors contributing to the increase in GHG emissions, rising by 159% and 131%, respectively. GDP per capita indirectly reflects variations in dietary changes and wastewater treatment capacity. For example, economic growth led to a decline in cereal intake along with an increase in meat consumption in nine provinces. Pollution output per GDP, GHGR per pollution removed, and population each played a role in the decrease of GHG emissions by 123%, 36%, and 30%, respectively. Overall, the influencing factors in the provinces were similar to those at the national level. Specifically, the rural population in Shanghai presented an increasing trend, which led to a 9% rise in GHG emissions. The wastewater treatment rate was the main driver of the increase in GHG emissions, with lower increases in GHGs observed in provinces with fewer improvements in wastewater treatment rates. Further, we explored the factors behind the differences among the Chinese provinces and cities using the Geographical Detector model. Population size and wastewater treatment rates were the main factors driving the differences in GHG emissions from rural domestic pollution treatment across provinces (Fig. 4e). Interestingly, the wastewater treatment rate was the dominant factor influencing provincial differences during the early period, but the population size gradually became the primary driver of these differences by 2022. With the continued improvement of the efficiency of wastewater treatment processes, the effects of population size and dietary patterns are expected to increase.

Discussion

The large rural population in China consumes significant amounts of food and detergents, placing substantial pressure on the environment. While wastewater treatment effectively reduces the pollution load, the increase in GHG emissions presents an unavoidable challenge8,32. Currently, the wastewater treatment rate in rural China remains low, contributing to high environmental pressure, but with considerable potential for an increase in GHG emission rates. We thus analyzed strategies for effective pollution reduction and GHG emission control, taking 2022 as the reference year (Figs. 4f and S41).

In terms of the dietary intake, the diet in rural China is primarily based on cereals, while meat and dairy consumption have been low according to the Chinese Food Guide Pagoda (2022). We assumed that the rural diet would be adjusted to align with the recommendations of the Chinese Food Guide Pagoda (2022) for a nutritionally balanced and healthy diet, which would lead to a decrease in the intake of C by 12.8%, N by 16.5%, and P by 16.8%, respectively. As a result, total GHG emissions would decline by 8.6%, and pollutants discharged into water bodies would reduce by ~18%. In 2022, the average per-capita disposable income in rural China reached 20,133 yuan, according to the National Bureau of Statistics. Based on the Chinese Food Guide Pagoda, adopting the recommended dietary structure would cost roughly 6000 yuan per person each year. However, many rural households produce or raise part of their vegetables, grains, and poultry themselves, substantially reducing their food expenditures. As rural incomes continue to grow, this self-sufficiency combined with rising purchasing power could support a long-term shift toward healthier diets. Therefore, promoting healthy diets that remain affordable for rural residents can simultaneously improve public health and support environmental sustainability.

Regarding the wastewater treatment capacity, the current rural domestic wastewater treatment rate remains low, with significant differences among provinces. By 2022, treatment rates in Zhejiang, Shanghai, and Tianjin exceeded 80%, while those in Qinghai and Guizhou remained below 20%. The access rate to sanitary toilets is still below 90% in nearly 60% of the provinces. The increase in wastewater treatment rates not only directly leads to higher GHG emissions from operational processes but also increases GHG emissions from construction activities. According to China’s Ministry of Ecology and Environment, rural China’s wastewater treatment rate reached 45% by 2024. This scenario is expected to increase total GHG emissions by a factor of 1.67, with GHGR accounting for 81.8% of total GHG emissions, while the pollutants discharged into water bodies will be reduced by ~20%. It is also projected that if the rural wastewater treatment rate reaches the level of 80% in the future, total GHG emissions from rural domestic pollution disposal will reach 105.5 Tg, with 57% of these emissions attributed to the construction of wastewater treatment systems. GHGR will display a more than threefold increase, accounting for 96.5% of total GHG emissions, while pollutants discharged into water bodies will be reduced by approximately 65%.

In the context of wastewater treatment, greenhouse gas emissions from electricity consumption currently contribute about 10% of total emissions. China is actively advancing clean-energy integration in treatment facilities: for example, the Jiangxia wastewater treatment plant in Wuhan has installed a photovoltaic system, achieving a clean-energy utilization rate of 45%, according to the National Development and Reform Commission. Leveraging more clean energy in rural wastewater treatment offers a promising pathway for both energy savings and further reductions in GHG emissions. Additionally, previous studies have indicated that removing 1 kg of COD can produce approximately 0.35 m³ of biogas, which is effective in reducing GHG emissions41,42. More resource-efficient methods, such as using sludge for building materials, could be explored in the sludge disposal process43,44. The decentralized nature of rural pollution discharge poses challenges for effective collection and treatment. To address this issue, a combination of tailored control strategies is recommended. For villages with relatively concentrated populations, centralized treatment solutions—such as constructing wastewater treatment facilities or transporting wastewater to nearby towns—can offer high pollutant removal efficiencies. In these cases, incorporating methane recovery technologies and clean energy sources is essential to minimize GHG emissions associated with treatment operations29,45. Villages located near urban centers may instead benefit from connecting to existing municipal wastewater systems, thereby avoiding the additional emissions and resource consumption required to build new facilities4,5. In contrast, for sparsely populated areas, decentralized approaches such as septic tanks coupled with constructed wetlands may provide a low-cost and energy-efficient option, with the treated effluent potentially reused for agricultural irrigation. This strategy also supports nutrient recycling in croplands and reduces the risk of untreated wastewater entering nearby waterways45. Moreover, decentralized treatment avoids the need for extensive pipeline networks and centralized infrastructure, thereby reducing both energy use and associated GHG emissions5,18,32. Considering the national socioeconomic trends, China has been experiencing an increase in the urbanization rate to 70%, which would lead to a continued reduction in the rural population and, consequently, a decrease in pollution emissions. Under this scenario, pollution outputs, total GHG emissions, and pollution discharged into water bodies could be reduced by approximately 13%, 7%, and 19%, respectively.

In assessing the efficiency of the different strategies with the composite trade-off index, we found that the scenario of healthier dietary habits, a 45% wastewater treatment rate, an 80% wastewater treatment rate, rural population reduction, and electricity reduction improved by 11.0%, 5.2%, 50.1%, 24.9%, and 9.9%, respectively, compared with the baseline scenario. The same mitigation measures combined -including an 80% wastewater treatment reduction rate- could result in a decrease of 92.4 Tg of GHG emissions, a decline in C, N, and P discharged into water bodies to 265, 396, and 12.9 Gg, respectively, and an average improvement of 70.1% in the composite trade-off index. We also note that by removing pollutants, wastewater treatment lowered the amount of contamination released into water bodies or soils. This reduction in pollutant loading indirectly diminished GHG emissions generated within the receiving environment.

Our calculations showed that the indirect reduction of GHG emissions accounted for approximately 33.6-43.3% of the GHG emissions from wastewater treatment systems over the past 10 years. Increases in pollution reduction typically correspond to larger declines in indirect GHG emissions. Thus, implementing a comprehensive suite of mitigation strategies could yield co-benefits for both pollution control and GHG emission reductions. Considering the significant variation in economic levels, population, and infrastructural conditions across provinces, as well as the relatively independent implementation of control measures, tailored approaches are required. Provinces with stronger economies and more advanced wastewater treatment facilities could prioritize dietary improvements of the public, optimize wastewater treatment technologies, and diversify treatment methods. Conversely, provinces with less developed economies and limited wastewater infrastructure should focus on expanding basic wastewater collection and treatment capacities. In addition, to more accurately assess GHG emissions from wastewater treatment systems, we recommend that regions with available resources monitor the wastewater plants to develop plant-level GHG emission factors. It is also important to recognize that discharged pollutants could be transported from upstream to downstream through runoff, while GHGs could disperse across extensive regions, often surpassing administrative boundaries. We recommend developing a management framework for integrated carbon and pollution emissions trading, using the watershed as the control unit and thus establishing better control on the cross-boundary transport of pollution.

World Bank data show that the proportion of populations using wastewater-treated sanitation facilities in countries such as India, Thailand, the Philippines, and Nigeria remains below 10%, while most developing countries still fall under 40%. These regions also have large rural populations, indicating that rural domestic wastewater management continues to face substantial infrastructure and resource challenges. Evidence from China demonstrates that rural wastewater treatment can significantly improve water quality, yet it may also generate unintended greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions during treatment processes. To better understand and optimize these complex trade-offs, we recommend applying our proposed framework to conduct a global assessment of the co-benefits of rural wastewater treatment. Such an assessment would provide critical insights into its implications for rural dietary health, environmental quality, and GHG emissions across diverse geographic and socioeconomic contexts, ultimately offering valuable guidance for engineering design, policy development, and environmental management worldwide.

Methods

Modelling framework

We developed an integrative modeling framework to quantify the pollution cycles and GHG emissions across the entire chain of rural domestic pollution disposal (Fig. 1). The system boundaries of the framework are shown in Fig. 5.

Rural domestic pollution stems from food intake and non-food use7,23,27. The pollutants of concern are carbon (C), nitrogen (N), and phosphorus (P). Food intake is used to estimate the pollution excretion output, which is calculated by subtracting the amount absorbed by the human body or released through respiration from the total food intake7,46,47,48. Non-food use involves detergents, which are discharged in the form of wastewater7,27. Rural domestic pollution disposal follows three main pathways. The first pathway occurs in areas with access to sanitary toilets and wastewater treatment systems, similar to urban areas5. High-concentration wastewater is collected and treated by wastewater treatment systems, while the lower-concentration tailwater being discharged into receiving water bodies. In parallel, the construction and operation of wastewater treatment systems emit significant amounts of greenhouse gases. It is important to note that reduced pollutants are not simply eliminated; instead, they are released into the atmosphere or accumulate in the sludge. Moreover, different sludge disposal methods lead to alterations in the pollution cycles and GHG emissions. The second pathway takes place in areas where sanitary toilets are available, but wastewater treatment systems are lacking. The untreated pollutants are discharged directly into surface water as nonpoint source pollution, increasing the pollution load of water bodies and resulting in additional GHG emissions. The third pathway is observed in areas without sanitary toilets and wastewater treatment systems. Rural domestic pollution is recycled into the environment as organic fertilizers, which migrate to surface water, groundwater, and the atmosphere through runoff, leaching, and soil respiration, while GHGs are generated. Different pollution disposal methods result in distinct pollution cycle processes and GHG emissions. The final destinations of pollutants include surface water, groundwater, soil, and the atmosphere. The greenhouse gases involved are methane, carbon dioxide, and nitrous oxide, with biogenic carbon dioxide being considered only in the pollution cycle analysis and excluded from the GHG emissions count1,5,18. In summary, we developed an integrative modeling framework, with the advantage of simultaneously evaluating carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus cycle processes, as well as methane, nitrous oxide, and carbon dioxide emissions (Supplementary Note 1 and Figure S1).

Where \({{RPO}}_{i}\) is total rural domestic pollution output of pollutant i; \({{RPI}}_{{foodi}}\) is total input of pollutant i from food intake; \({{RPI}}_{{nonfoodi}}\) is total input of pollutant i from detergents; \({f}_{1i}\) is absorption/respiration emission coefficients for pollutant i; \({{Untreated}}_{i},{{Recycled}}_{i},\) \({{Untreated}}_{i}\) represent the untreated, recycled, and treated fractions of pollutant i, respectively; \({{Surface\; water}}_{i},\) \({{Ground\; water}}_{i},\,{{Soil}}_{i},\) \({{Atmosphere}}_{i}\) denote the amounts of pollutant i flowing to surface water, groundwater, soil and the atmosphere, respectively; i = C, N, P; \({{GHG}}_{T}\) is total GHG emissions; \({{GHG}}_{{UN}}\), \({{GHG}}_{{RC}}\), \({{GHG}}_{R}\) denote GHG emissions from untreated, recycled and treated pollution; \({{CH}}_{4}{eq}\), \({N}_{2}{Oeq}\), \({{CO}}_{2}\) mean methane, carbon monoxide, carbon dioxide emissions expressed in units of Gg of CO2-eq.

Assessment of co-benefits of pollution reduction and GHG emission control

Based on the intertwined processes of the rural domestic pollution cycles and GHG emissions, it is evident that different pollution disposal methods lead to varying environmental and climate impacts (Figure S1). The first model assumes that all rural domestic pollution is treated by the wastewater treatment system and discharged as tailwater (in accordance with wastewater discharge standards), which results in fewer pollutants being discharged into water bodies and GHG emissions are the highest. The second model hypothesizes that all rural domestic pollution (untreated) is recycled in the environment as fertilizer, leading to a small amount of pollutants entering water bodies through runoff and emitting approximately 46% of the actual GHG emissions. However, the direct use of fertilizer may degrade the residential experience due to the release of odors, while fertilizers that accumulate in the soil will continue to drive pollutants into water bodies through runoff in the long run. The third model posits that all rural domestic pollution (untreated) is discharged directly into water bodies, introducing the highest pollutant outputs and approximately 60% of the actual GHG emissions. China’s current rural domestic pollution is managed through a combination of the three models, with pollutants discharged into water bodies and GHG emissions falling within the range defined by these models. The key to assessing co-benefits lies in the simultaneous consideration of both the characteristics of pollution reduction and GHG emissions5,18,31,39. Assessing the co-benefits of rural domestic pollution treatment is inherently complex because wastewater systems simultaneously reduce pollutant discharges and generate greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions1,4,7,39. To support climate mitigation and environmental protection goals, the objective is to maximize net benefits—reducing GHG emissions and pollutant loads while restoring degraded waterbodies. Based on this rationale, we selected four key indicators—GHG emissions, pollution output, pollution reduction, and pollutant discharge—to represent both climate and environmental dimensions and incorporated them into a composite index. To enable comparison across provinces and municipalities, and to control for scale differences, all indicators were normalized; lower values indicate stronger co-benefits. To further evaluate trade-offs over the past decade, we introduce three additional indices: (i) a GHG emissions index, defined as total GHG emissions divided by total pollution output; (ii) an environmental index, expressed as the ratio of pollution discharged to surface waters relative to pollution reduction; and (iii) a population index, calculated as the ratio of the rural population in a specific province and year to the maximum provincial average population nationwide (derived from China’s maximum total population from 2013–2022 divided by the number of provinces). Together, these indices allow the derivation of a composite trade-off index that reflects the relative importance of jointly controlling domestic pollution and GHG emissions. As with the previous index, lower values represent greater co-benefits. Therefore, our proposed composite trade-off index effectively reflects the importance of joint control of domestic pollution and GHG emissions, and the smaller the value, the greater the co-benefits.

where \({I}_{{trade}-{off}}\) denotes the composite trade-off index; \({I}_{{GHG\; emissions}}\) is GHG emissions index;\({I}_{{Environment}}\) is environmental index; \({I}_{{Population}}\) is population index; \({{Surface\; water}}_{{Pollution}}\), \({{Reduced}}_{{Pollution}}\), \({{RPO}}_{{Pollution}}\) represent the pollutant flowing into surface waters, reduced pollutant by wastewater treatment system, total rural domestic pollution output, respectively; Population and GHGT refer to the population size and total GHG emissions, respectively, for any given province, city, or country being analyzed. Here, i=COD, TN, TP; \({w}_{i}\) is determined by the Environmental quality standards for surface water (GB3838-2002); \({Maximum\; provincial\; average\; population}\) is the maximum average rural population across provinces in China.

Geographical detector model and log-mean divisia index (LMDI) method

The Geographical Detector model was employed to analyze the impacts of population, pollution output per capita, wastewater treatment rate, fixed investment in wastewater treatment per capita, and GDP per capita on GHG emissions49,50,51. This model was also used to explore the causes of provincial differences in GHG emissions. Geographical detector model was performed in an Excel package (http://www.geodetector.cn/Download.html). The LMDI method was used to assess the relative importance of various regulatory factors influencing GHG emissions, which can be decomposed using a Kaya-type identity.

where \({{GHG}}_{R}\) represents GHG emissions from wastewater treatment system in rural area; \({{Reduced}}_{{Pollution}}\) is reduced pollutant by wastewater treatment system; \({{RPO}}_{{Pollution}}\) is the total rural domestic pollution output; RGDP is rural gross domestic product; Pop is the population size. The factors considered were the GHG emission intensity (\(\frac{{{GHG}}_{T}}{{{Reduced}}_{{Pollution}}}\)); pollution reduction rate (\(\frac{{{Reduced}}_{{Pollution}}}{{{RPO}}_{{Pollution}}}\)); pollution discharge intensity; (\(\frac{{{RPO}}_{{Pollution}}}{{RGDP}}\)); economic development level (\(\frac{{RGDP}}{{Pop}}\)); and population size (\({Pop}\)).

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files).

References

Song, C., Zhu, J.-J., Yuan, Z., van Loosdrecht, M. C. M. & Ren, Z. J. Defining and achieving net-zero emissions in the wastewater sector. Nat. Water 2, 927–935 (2024).

Salerno, J. et al. Rural migration under climate and land systems change. Nat. Sustain. 7, 1092–1101 (2024).

Su, S. et al. Carbon emissions from rural wastewater treatment using the anoxic-anaerobic-oxic membrane bioreactor process. J. Clean. Prod. 510, 145640 (2025).

Chen, S. et al. Decoupling wastewater-related greenhouse gas emissions and water stress alleviation across 300 cities in China is challenging yet plausible by 2030. Nat. Water 1, 534–546 (2023).

Wang, T. et al. Evaluation of the role of urban domestic wastewater treatment systems for greenhouse gases emissions in China. Ecol. Inform. 81, 102571 (2024).

Li, P. et al. Exploration of sustainable driving path of rural domestic wastewater treatment-from the perspective of life cycle assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 434, 140403 (2024).

Liu, X. et al. Exploring wastewater nitrogen and phosphorus flows in urban and rural areas in China for the period 1970 to 2015. Sci. Total Environ. 907, 168091 (2024).

Xu, W. et al. Globally elevated greenhouse gas emissions from polluted urban rivers. Nat. Sustain. 7, 938–948 (2024).

Huang, J., Xu, C.-c., Ridoutt, B. G., Wang, X.-c. & Ren, P.-a. Nitrogen and phosphorus losses and eutrophication potential associated with fertilizer application to cropland in China. J. Clean. Prod. 159, 171–179 (2017).

Morée, A. L., Beusen, A. H. W., Bouwman, A. F. & Willems, W. J. Exploring global nitrogen and phosphorus flows in urban wastes during the twentieth century. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 27, 836–846 (2013).

IPCC. 2019 Refinement to the 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories (2019).

Su, Q. et al. Water–energy–carbon nexus: greenhouse gas emissions from integrated urban drainage systems in China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 2093–2104 (2023).

Salvetti, M. Going from energy efficiency to climate neutrality on the way to decarbonizing the wastewater sector. Nat. Water 2, 913–914 (2024).

Garrido-Baserba, M. et al. Using water and wastewater decentralization to enhance the resilience and sustainability of cities. Nat. Water 2, 953–974 (2024).

Li, H. et al. Methane and nitrous oxide emissions from municipal wastewater treatment plants in China: a plant-level and technology-specific study. Environ. Sci. Ecotechnol. 20, 100345 (2024).

Tong, Y. et al. Mitigating greenhouse gas emissions from municipal wastewater treatment in China. Environ. Sci. Ecotechnol. 20, 100341 (2024).

Yu, Q., Li, S. & Chen, N. Urbanization and greenhouse gas emissions from municipal wastewater in coastal provinces of China: Spatiotemporal patterns, driving factors, and mitigation strategies. Environ. Res. 259, 119398 (2024).

Du, W.-J. et al. Spatiotemporal pattern of greenhouse gas emissions in China’s wastewater sector and pathways towards carbon neutrality. Nat. Water 1, 166–175 (2023).

Shrestha, A. et al. Estimation of greenhouse gases emission from domestic wastewater in Nepal: A scenario-based analysis applicable for developing countries. Chemosphere 300, 134501 (2022).

Hu, M. et al. Long-term (1980–2015) changes in net anthropogenic phosphorus inputs and riverine phosphorus export in the Yangtze River basin. Water Res. 177, 115779 (2020).

Wang, Z. et al. Phosphorus flow analysis in the maize based food-feed-energy systems in China. Environ. Res. 184, 109319 (2020).

Van Drecht, G., Bouwman, A. F., Harrison, J. & Knoop, J. M. Global nitrogen and phosphate in urban wastewater for the period 1970 to 2050. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 23, https://doi.org/10.1029/2009gb003458 (2009).

Gu, B. et al. Nitrogen footprint in China: food, energy, and nonfood goods. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 9217–9224 (2013).

Zhao, H. et al. China’s future food demand and its implications for trade and environment. Nat. Sustain. 4, 1042–1051 (2021).

Bizimana, F. et al. Estimating food nitrogen and phosphorus footprints and budgeting nitrogen and phosphorus flows of Rwanda’s agricultural food system during 1961–2020. Sci. Total Environ. 906, 167693 (2024).

Chen, X. et al. Mitigating phosphorus pollution from detergents in the surface waters of China. Sci. Total Environ. 804, 150125 (2022).

Liu, X. et al. Intensification of phosphorus cycling in China since the 1600s. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 113, 2609–2614 (2016).

Wang, T. et al. Dynamic spatiotemporal change of net anthropogenic phosphorus inputs and its response of water quality in the Liao river basin. Chemosphere 331, 138757 (2023).

Xia, B. et al. Sewage leakage challenges urban wastewater management as evidenced by the Yangtze River basin of China. npj Clean. Water 7, 99 (2024).

Liao, C., Xia, Y. & Wu, D. Nitrogen flows associated with food production and consumption system of Shanghai. Environ. Pollut. 279, 116906 (2021).

Zhang, Z. et al. Nitrogen flow in the food production and consumption system within the Yangtze River Delta city cluster: Influences of cropland and urbanization. Sci. Total Environ. 824, 153861 (2022).

Guo, D. et al. Revisiting China’s domestic greenhouse gas emission from wastewater treatment: A quantitative process life-cycle assessment. Sci. Total Environ. 876, 162597 (2023).

Ding, T., Ning, Y. & Zhang, Y. Estimation of greenhouse gas emissions in China 1990–2013. Greenh. Gases: Sci. Technol. 7, 1097–1115 (2017).

Yang, M. et al. Greenhouse gas emissions from wastewater treatment plants in China: Historical emissions and future mitigation potentials. Resources Conserv. Recycl. 190, 106794 (2023).

Hua, H. et al. Advancing greenhouse gas emission factors for municipal wastewater treatment plants in China. Environ. Pollut. 295, 118648 (2022).

Wang, D. et al. Greenhouse gas emissions from municipal wastewater treatment facilities in China from 2006 to 2019. Sci. Data 9, 317 (2022).

Zhao, X. et al. China’s urban methane emissions from municipal wastewater treatment plant. Earth’s. Future 7, 480–490 (2019).

Huang, Y., Meng, F., Liu, S., Sun, S. & Smith, K. China’s enhanced urban wastewater treatment increases greenhouse gas emissions and regional inequality. Water Res. 230, 119536 (2023).

Luo, Z., Hu, S., Chen, D. & Zhu, B. From production to consumption: a coupled human–environmental nitrogen flow analysis in China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 2025–2035 (2018).

Ma, L. et al. Impacts of urban expansion on nitrogen and phosphorus flows in the food system of Beijing from 1978 to 2008. Glob. Environ. Change 28, 192–204 (2014).

Abdeshahian, P., Lim, J. S., Ho, W. S., Hashim, H. & Lee, C. T. Potential of biogas production from farm animal waste in Malaysia. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 60, 714–723 (2016).

Ahmed, Y., Yaakob, Z., Akhtar, P. & Sopian, K. Production of biogas and performance evaluation of existing treatment processes in palm oil mill effluent (POME). Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 42, 1260–1278 (2015).

Ji, M. et al. Water-energy-greenhouse gas nexus of a novel high-rate activated sludge-two-stage vertical up-flow constructed wetland system for low-carbon wastewater treatment. Water Res. 229, 119491 (2023).

Wang, Q. et al. Carbon source recovery from waste sludge reduces greenhouse gas emissions in a pilot-scale industrial wastewater treatment plant. Environ. Sci. Ecotechnol. 14, 100235 (2023).

Tortajada, C. Contributions of recycled wastewater to clean water and sanitation Sustainable Development Goals. npj Clean. Water 3, 22 (2020).

Cai, Q. et al. The impact of human and livestock respiration on CO2 emissions from 14 global cities. Carbon Balance Manag. 17, 17 (2022).

Auclair, O. & Burgos, S. A. Carbon footprint of Canadian self-selected diets: comparing intake of foods, nutrients, and diet quality between low- and high-greenhouse gas emission diets. J. Clean. Prod. 316, 128245 (2021).

Gu, B., Ju, X., Chang, J., Ge, Y. & Vitousek, P. M. Integrated reactive nitrogen budgets and future trends in China. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 8792–8797 (2015).

Zhang, H. et al. Understanding and extending the geographical detector model under a linear regression framework. Int. J. Geograph. Inf. Sci. 37, 2437–2453 (2023).

He, H. & Myers, R. J. Log mean divisia index decomposition analysis of the demand for building materials: application to concrete, dwellings, and the U.K. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 2767–2778 (2021).

Qiu, L. et al. Substantial terrestrial carbon emissions from global expansion of impervious surface area. Nat. Commun. 15, 6456 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to reviewers. The views and ideas expressed herein are solely of the authors and do not represent the ideas of the funding agencies in any forms. This study was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (42277383), National Science and Technology Major Project for Comprehensive Environmental Management in Jing-Jin-Ji (2025ZD1206001), Hebei Provincial Water Conservancy Science and Technology Program Project (HBSL 2025-02), Science and Technology Plan Project of Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region (2025YFHH0129), China Scholarship Council (202106065001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.-T.X., G.A., and L.Q. conceived the idea. W.-T.X., W.S., and F.Y. collected and analysed the data. W.-T.X., G.A., W.S., F.Y., X.X., W.Z., W.J., S.G., L.Q., S.Y., Z.J., Y.J. and L.L. co-wrote the manuscript. and G.A., L.Q., and W.-T.X. reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, T., Su, G., Wang, S. et al. China’s enhanced wastewater treatment capacity may accelerate greenhouse gas emissions from rural domestic pollution. npj Clean Water 9, 10 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41545-025-00540-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41545-025-00540-9