Abstract

China’s Chang’e-6 (CE-6) mission successfully returned the first lunar samples from the South Pole–Aitken basin on the Moon’s farside. Determining the provenance and evolution of the samples will play a crucial role in guiding effective laboratory analyses. Here we conduct a comprehensive search for source impact craters of the CE-6 samples on global, regional and local scales, and systematically model the formation, migration, mixing and maturation of regolith in the landing region driven by continuous bombardment and solar wind irradiation. A catalogue of 1,674 major source craters with ejecta source depths of up to 3 km was established, which cumulatively delivered materials 53.4 ± 15.7 cm thick to the CE-6 landing site. The returned samples are estimated to comprise ~93.3% local basalts, 6.1% South Pole–Aitken basin materials that are likely to contain mantle components and 0.6% highland feldspathic materials from outside the South Pole–Aitken basin. Modelled elemental abundance depth profiles show that the exotic materials are primarily concentrated at depths of 2.5–3 m, with a portion within the sampling depth of 1 m. The estimated exposure time in the top 1 mm is \({2.1}_{-0.9}^{+1.1}\,{\rm{Myr}}\) for the surficial scooped samples and shorter for deeper drilled samples. These findings establish a crucial foundation for CE-6 sample analysis and interpretation, offering key insights into the provenance of exotic materials and the space weathering process on the Moon’s farside.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera and SELENE-LRO merged digital elevation model data are available at the NASA Planetary Data System Geosciences Node at https://pds-geosciences.wustl.edu/dataserv/moon.html. The Kaguya Multiband Imager and Terrain Camera data can be accessed at https://darts.isas.jaxa.jp/app/pdap/selene/. The Th abundance data from Lunar Prospector are available at https://pds-geosciences.wustl.edu/missions/lro/lola.htm. The data derived in this study are available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14963665 (ref. 68). Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Yue, Z. et al. Geological context of the Chang’e-6 landing area and implications for sample analysis. Innovation 5, 100663 (2024).

Zeng, X. et al. Landing site of the Chang’e-6 lunar farside sample return mission from the Apollo basin. Nat. Astron. 7, 1188–1197 (2023).

Li, C. et al. Nature of the lunar farside samples returned by the Chang’E-6 mission. Natl Sci. Rev. 11, nwae328 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. A catalogue of impact craters and surface age analysis in the Chang’e-6 landing area. Remote Sens. 16, 2014 (2024).

Sun, L. & Lucey, P. G. Lunar mantle composition and timing of overturn indicated by Mg# and mineralogy distributions across the South Pole-Aitken basin. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 643, 118931 (2024).

Orgel, C. et al. Characterization of high-priority landing sites for robotic exploration missions in the Apollo basin, Moon. Planet. Sci. J. 5, 29 (2024).

Moriarty, D. P. III, Dygert, N., Valencia, S. N., Watkins, R. N. & Petro, N. E. The search for lunar mantle rocks exposed on the surface of the Moon. Nat. Commun. 12, 4659 (2021).

Ohtake, M. et al. Geologic structure generated by large‐impact basin formation observed at the South Pole‐Aitken basin on the Moon. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 2738–2745 (2014).

Qian, Y. et al. Long-lasting farside volcanism in the Apollo basin: Chang’e-6 landing site. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 637, 118737 (2024).

Guo, Z. et al. Space-weathered rims on lunar ilmenite as an indicator for relative exposure ages of regolith. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 426 (2024).

Pieters, C. M. & Noble, S. K. Space weathering on airless bodies. J. Geophys. Res. 121, 1865–1884 (2016).

Neukum, G., Ivanov, B. A. & Hartmann, W. K. Cratering records in the inner solar system in relation to the lunar reference system. Space Sci. Rev. 96, 55–86 (2001).

Jolliff, B. L., Gillis, J. J., Haskin, L. A., Korotev, R. L. & Wieczorek, M. A. Major lunar crustal terranes: surface expressions and crust-mantle origins. J. Geophys. Res. 105, 4197–4216 (2000).

Wieczorek, M. A. et al. The crust of the Moon as seen by GRAIL. Science 339, 671–675 (2013).

Moriarty, D. P.III & Pieters, C. M. The character of South Pole-Aitken Basin: patterns of surface and subsurface composition. J. Geophys. Res. 123, 729–747 (2018).

Moriarty, D. III et al. Evidence for a stratified upper mantle preserved within the South Pole‐Aitken basin. J. Geophys. Res. 126, e2020JE006589 (2021).

Moriarty, D. & Pieters, C. Proc. 45th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (Lunar and Planetary Institute, 2014).

Moriarty, D. & Pieters, C. Proc. 47th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (Lunar and Planetary Institute, 2016).

Hurwitz, D. M. & Kring, D. A. Differentiation of the South Pole-Aitken basin impact melt sheet: implications for lunar exploration. J. Geophys. Res. 119, 1110–1133 (2014).

Melosh, H. J. et al. South Pole–Aitken basin ejecta reveal the Moon’s upper mantle. Geology 45, 1063–1066 (2017).

Meyer, H. M., Denevi, B. W., Boyd, A. K. & Robinson, M. S. The distribution and origin of lunar light plains around Orientale basin. Icarus 273, 135–145 (2016).

Jia, Z. et al. Geologic context of Chang’e-6 candidate landing regions and potential non-mare materials in the returned samples. Icarus 416, 116107 (2024).

Chen, Y. et al. Chang’e-5 lunar samples shed new light on the Moon. Innov. Geosci. 1, 100014 (2023).

Jia, B. J. et al. On the provenance of the Chang’E-5 lunar samples. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 596, 117791 (2022).

Fa, W. Z. & Jin, Y. Q. Quantitative estimation of helium-3 spatial distribution in the lunar regolith layer. Icarus 190, 15–23 (2007).

Melosh, H. J. Impact Cratering: A Geologic Process (Oxford Univ. Press, 1989).

Sharpton, V. L. Outcrops on lunar crater rims: implications for rim construction mechanisms, ejecta volumes and excavation depths. J. Geophys. Res. 119, 154–168 (2014).

Maxwell, D. E. Simple Z model for cratering, ejection, and the overturned flap. In Impact and Explosion Cratering (eds Roddy, D. J. et al.) 1003–1008 (Pergamon Press, 1977).

Ohtake, M. et al. Asymmetric crustal growth on the Moon indicated by primitive farside highland materials. Nat. Geosci. 5, 384–388 (2012).

McKay, D. S. et al. in Lunar Source-Book: A User’s Guide to the Moon (eds Heiken, G. H. et al.) Ch. 7 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1991).

Zhang, M., Fa, W. & Eke, V. R. Modeling the evolution of lunar regolith: 1. Formation mechanism through individual simple impact craters. J. Geophys. Res. 128, e2023JE007850 (2023).

Zhang, M., Fa, W., Barnard, E. M. & Eke, V. R. Modeling the evolution of lunar regolith: 2. Growth rate and spatial distribution. J. Geophys. Res. 128, e2023JE008035 (2023).

Guo, D. et al. Geological investigation of the lunar Apollo basin: from surface composition to interior structure. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 646, 118986 (2024).

Liu, T., Wünnemann, K. & Michael, G. 3D-simulation of lunar megaregolith evolution: quantitative constraints on spatial variation and size of fragment. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 597, 117817 (2022).

Karthi, A. Proc. 50th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (Lunar and Planetary Institute, 2019).

Keller, L. P., Berger, E. L., Zhang, S. & Christoffersen, R. Solar energetic particle tracks in lunar samples: a transmission electron microscope calibration and implications for lunar space weathering. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 56, 1685–1707 (2021).

Moriarty, D. P. III & Pieters, C. M. The nature and origin of mafic mound in the South Pole‐Aitken Basin. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 7907–7915 (2015).

Vaughan, W. M. & Head, J. W. Impact melt differentiation in the South Pole-Aitken basin: some observations and speculations. Planet. Space Sci. 91, 101–106 (2014).

Denevi, B. W., Robinson, M. S., Boyd, A. K., Blewett, D. T. & Klima, R. L. The distribution and extent of lunar swirls. Icarus 273, 53–67 (2016).

Tsunakawa, H., Takahashi, F., Shimizu, H., Shibuya, H. & Matsushima, M. Surface vector mapping of magnetic anomalies over the Moon using Kaguya and Lunar Prospector observations. J. Geophys. Res. 120, 1160–1185 (2015).

Wieczorek, M. A. Strength, depth, and geometry of magnetic sources in the crust of the Moon from localized power spectrum analysis. J. Geophys. Res. 123, 291–316 (2018).

Yue, Z. et al. Updated lunar cratering chronology model with the radiometric age of Chang’e-5 samples. Nat. Astron. 6, 541–545 (2022).

Le Feuvre, M. & Wieczorek, M. A. Nonuniform cratering of the Moon and a revised crater chronology of the inner Solar System. Icarus 214, 1–20 (2011).

Zhang, M., Jia, B., Eke, V. R. & Fa, W. AGU Fall Meeting 2023 (American Geophysical Union, 2023).

Lemelin, M. et al. The compositions of the lunar crust and upper mantle: spectral analysis of the inner rings of lunar impact basins. Planet. Space Sci. 165, 230–243 (2019).

Xu, Y. et al. High abundance of solar wind-derived water in lunar soils from the middle latitude. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2214395119 (2022).

Xie, M., Liu, T. & Xu, A. Ballistic sedimentation of impact crater ejecta: implications for the provenance of lunar samples and the resurfacing effect of ejecta on the lunar surface. J. Geophys. Res. 125, e2019JE006113 (2020).

Yang, X., Fa, W. Z., Du, J., Xie, M. G. & Liu, T. T. Effect of topographic degradation on small lunar craters: implications for regolith thickness estimation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL095537 (2021).

Cai, Y. & Fa, W. Meter‐scale topographic roughness of the Moon: the effect of small impact craters. J. Geophys. Res. 125, e2020JE006429 (2020).

Zong, K. et al. Bulk compositions of the Chang’E-5 lunar soil: insights into chemical homogeneity, exotic addition, and origin of landing site basalts. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 335, 284–296 (2022).

Fassett, C. I. & Thomson, B. J. Crater degradation on the lunar maria: topographic diffusion and the rate of erosion on the Moon. J. Geophys. Res. 119, 2255–2271 (2014).

Fassett, C. I., Minton, D. A., Thomson, B. J., Hirabayashi, M. & Watters, W. A. Proc. 49th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (Lunar and Planetary Institute, 2018).

Petro, N. E. & Pieters, C. M. Modeling the provenance of the Apollo 16 regolith. J. Geophys. Res. 111, E09005 (2006).

Costello, E. S., Ghent, R. R., Hirabayashi, M. & Lucey, P. G. Impact gardening as a constraint on the age, source, and evolution of ice on Mercury and the Moon. J. Geophys. Res. 125, e2019JE006172 (2020).

Hu, J. Y., Leya, I., Dauphas, N., Rae, A. S. & Williams, H. M. Constraints on lunar regolith resurfacing from coupled modeling of stochastic gardening and neutron capture effects. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 375, 201–216 (2024).

O’Brien, P. & Byrne, S. Physical and chemical evolution of lunar mare regolith. J. Geophys. Res. 126, e2020JE006634 (2021).

Huang, Y. H. et al. Heterogeneous impact transport on the Moon. J. Geophys. Res. 122, 1158–1180 (2017).

Robbins, S. J. A new global database of lunar impact craters> 1–2 km: 1. Crater locations and sizes, comparisons with published databases, and global analysis. J. Geophys. Res. 124, 871–892 (2019).

Fortezzo, C., Spudis, P. & Harrel, S. Proc. 51st Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (Lunar and Planetary Institute, 2020).

Losiak, A. et al. Proc. 40th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (Lunar and Planetary Institute, 2009).

Hayne, P. O. et al. Global regolith thermophysical properties of the Moon from the Diviner Lunar Radiometer Experiment. J. Geophys. Res. 122, 2371–2400 (2017).

Lemelin, M., Lucey, P. G., Song, E. & Taylor, G. J. Lunar central peak mineralogy and iron content using the Kaguya Multiband Imager: reassessment of the compositional structure of the lunar crust. J. Geophys. Res. 120, 869–887 (2015).

Otake, H., Ohtake, M. & Hirata, N. Proc. 43rd Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (Lunar and Planetary Institute, 2012).

Yang, C. et al. Comprehensive mapping of lunar surface chemistry by adding Chang’e-5 samples with deep learning. Nat. Commun. 14, 7554 (2023).

Michael, G. G. Planetary surface dating from crater size–frequency distribution measurements: multiple resurfacing episodes and differential isochron fitting. Icarus 226, 885–890 (2013).

Du, J. et al. Thickness of lunar mare basalts: new results based on modeling the degradation of partially buried craters. J. Geophys. Res. 124, 2430–2459 (2019).

Kirchoff, M. R. et al. Ages of large lunar impact craters and implications for bombardment during the Moon’s middle age. Icarus 225, 325–341 (2013).

Zhang, M., Fa, W. & Jia, B. Data for provenance and evolution of lunar regolith at the Chang’e-6 sampling site. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14963665 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This research is funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under grant number 12173004. This is Planetary Remote Sensing Laboratory, Peking University, contribution 30.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: W.F. Data acquisition: M.Z. and B.J. Formal analysis: M.Z. and W.F. Investigation: M.Z., W.F. and B.J. Methodology: M.Z. and W.F. Writing: M.Z. and W.F. Funding acquisition: W.F.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Astronomy thanks Daniel Moriarty and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

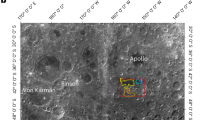

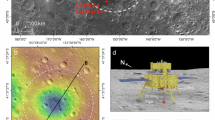

Extended Data Fig. 1 Geological context of the CE-6 landing region.

a, The SPA basin, Mg-pyroxene annulus, and SPACA boundaries are outlined by the green, purple and pink curves, respectively. The inner and outer rings of the Apollo basin are depicted in white dashed curves. b, The five mare basalt units within the Apollo basin are depicted in blue curves. The red star shows the CE-6 landing site in both panels.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Reflectance characteristics of impact craters with different degradation stages.

a, a fresh (upper) and degraded (lower) impact crater in a LROC NAC image (ID: M166854798L). b, Histogram of the reflectance for two impact craters in panel a.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Elemental abundance of all the 1674 source craters.

(a) FeO, (b) TiO2, and (c) Mg#. The color represents the thickness of ejecta delivered to the CE-6 landing site and the size of the circles increases with increasing crater diameter.

Extended Data Fig. 4 The modeled regolith evolution process over a 2 km×2 km area across the CE-6 landing site.

a-b, Modeled (a) topography and (b) regolith thickness at present from one typical realization. c, Histogram of regolith thickness with a 0.1 m bin size from all the 400 simulations. The blue and red lines show the median and mean thickness, respectively. d, Growth dynamics of regolith thickness from all the 400 simulations. Upper panel: the mean, median, and quartiles of regolith thickness with time. The shaded regions show the mean difference between each individual simulation and the average of all the 400 simulations. Lower panel: the mean growth rate of lunar regolith generated by primary (light green line) and secondary (pink line) craters. The peaks in pink correspond to the formation of large craters outside the landing area, which are labeled except for the unnamed craters.

Extended Data Fig. 5 The observed and modeled crater populations within the CE-6 landing region of 2 km across.

a, Size-frequency distribution of the observed craters (red dots). b, Size-frequency distributions of the modeled primary (red dots) and secondary (blue dots) craters. The black line represents the Neukum production function of 2.4 Ga.

Extended Data Fig. 6 The modeled regolith exposure time at various depths based on a representative model realization.

a, Surface, b, 10 cm, c, 20 cm, d, 30 cm, e, 40 cm, and f, 50 cm. The red star represents the CE-6 landing site.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Evolution of mean exposure time of the surficial regolith layer within the simulation area from 2.4 Ga to present.

The gray line shows the result of each individual simulation and the red line represents the mean value. The shaded region shows the mean difference between each individual realization and the average of all the 400 simulations.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Distribution of magnetic field strength at lunar surface.

The red curves show swirl regions. The white curve and circles show the boundary of the SPA basin and the identified major source craters. The red star shows the CE-6 landing site.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Distribution of the optical maturity parameter (OMAT) over a 2 km×2 km area across the CE-6 (left) and CE-5 (right) landing sites.

The OMAT is calculated from the Kaguya MI data (∼14 m/pixel) using the algorithm of Lemelin et al. The yellow star represents the CE-6 and CE-5 landing sites.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Texts 1 and 2, Figs. 1–7, Tables 1 and 2, and references.

Supplementary Data 1

Source data for Supplementary Fig. 4.

Supplementary Data 2

Source data for Supplementary Fig. 5.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Source data for Fig. 1.

Source Data Fig. 2

Source data for Fig. 2.

Source Data Fig. 3

Source data for Fig. 3.

Source Data Fig. 4

Source data for Fig. 4.

Source Data Fig. 5

Source data for Fig. 5.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Source data for Extended Data Fig. 3.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4

Source data for Extended Data Fig. 4.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 5

Source data for Extended Data Fig. 5.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 7

Source data for Extended Data Fig. 7.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, M., Fa, W. & Jia, B. Provenance and evolution of lunar regolith at the Chang’e-6 sampling site. Nat Astron 9, 813–823 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-025-02525-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-025-02525-7

This article is cited by

-

A Submillimeter Iron Particle in Chang’e-6 Lunar Soil

Journal of Earth Science (2025)