Abstract

Atmospheric carbon has been detected in the optical spectra of six hydrogen-rich ultra-massive white dwarfs, revealing large carbon abundances (log(C/H) > −0.5) attributable to the convective dredge-up of internal carbon into thin hydrogen surface layers. These rare white dwarfs likely originate from stellar mergers, making them ‘smoking guns’ for one of the binary evolution channels leading to thermonuclear supernovae. However, optical spectroscopy can uncover only the most carbon-enriched objects, suggesting that many more merger remnants may masquerade as normal pure-hydrogen-atmosphere white dwarfs. Here we report the discovery of atmospheric carbon in a Hubble Space Telescope far-ultraviolet spectrum of WD 0525+526, a long-known hydrogen-rich ultra-massive white dwarf. The carbon abundance (log(C/H) = −4.62) is 4–5 dex lower than in the six counterparts and thus detectable only at ultraviolet wavelengths. We find that the total masses of hydrogen and helium in the envelope (10−13.8 and 10−12.6 of the total white dwarf mass, respectively) are substantially lower than those expected from single-star evolution, implying that WD 0525+526 is a merger remnant. Our modelling indicates that the low surface carbon abundance arises from an envelope structure in which a thin hydrogen-rich layer floats atop a semi-convection zone—a process that has been largely overlooked in white dwarfs. Our study highlights the importance of ultraviolet spectroscopy in identifying and characterizing merger remnants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The spacecraft Gaia has revealed the detailed structure of white dwarf cooling tracks in the Hertzsprung–Russell diagram1, uncovering a feature known as the Q-branch, an overdensity associated with white dwarfs of all masses that experience a cooling delay of about 1 Gyr owing to core crystallization and related physical processes2 (Fig. 1). The ultra-massive (≥1.1 solar masses (M⊙)) members of the Q-branch were found to have large space velocity dispersions indicative of abnormally old ages, implying that 5–9% of all ultra-massive white dwarfs experience an additional cooling delay of at least 8 Gyr (ref. 3). The leading explanation for this extra delay is the release of gravitational energy through the solid–liquid distillation of 22Ne triggered by crystallization in white dwarfs with carbon–oxygen cores4,5. This subpopulation of delayed white dwarfs is interpreted as being the descendants of certain types of stellar mergers, such as the merger of a white dwarf with a subgiant star6. However, it is challenging to unambiguously attribute a merger history to individual ultra-massive white dwarfs, as their core compositions (carbon–oxygen or oxygen–neon) are normally obscured by layers of helium and hydrogen. Consequently, the fraction of stellar mergers on the Q-branch and the details of their past evolution remain uncertain.

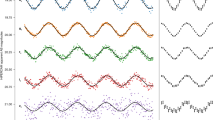

WD 0525+526 is indicated by a red star, while the six published white dwarfs with spectral type DAQ8,9,10 are shown as blue circles. a, Gaia Hertzsprung–Russell diagram showing the DAQ stars and white dwarfs lying within 100 pc (ref. 17; grey dots) where Gabs (absolute), GBP and GRP are the magnitudes in Gaia filters. The cooling track of a standard 0.6 M⊙ hydrogen-atmosphere white dwarf38 is overlaid as a solid black line, and similar cooling tracks for 1.0 and 1.25 M⊙ white dwarfs with thinner hydrogen and helium envelope layers5 are displayed as dashed black lines. The solid magenta curves indicate where standard white dwarf models (without distillation) have crystallized mass fractions of 20% (top curve) and 80% (bottom curve)38. The solid green curves show the beginning (top curve) and end (bottom curve) of the distillation process triggered by crystallization in ultra-massive white dwarf models5. We note that five DAQ stars are slightly brighter than the predicted onset of distillation; this is because the models displayed here assume a pure-hydrogen atmosphere and fixed envelope layer masses, while the DAQ white dwarfs contain atmospheric carbon and have different envelope structures. In particular, the redistribution of flux from ultraviolet to optical wavelengths by carbon lines makes white dwarfs brighter in Gaia Gabs. b, Photospheric carbon abundances of the DAQ stars as a function of effective temperature (Teff) with 1σ error bars for the measurements. The carbon abundance of WD 0525+526 is several orders of magnitude lower than those of the previously known cooler DAQ white dwarfs and could only be detected in the HST far-UV spectrum.

The most direct observational evidence of a stellar merger history comes from the surface composition. Among ultra-massive Q-branch white dwarfs, some have apparently typical hydrogen atmospheres, but others exhibit unusually carbon-enriched atmospheres3,7. Among these are six white dwarfs that have mixed hydrogen–carbon (DAQ type) atmospheres with number abundance ratios of log(C/H) = −0.5 to 0.97 (refs. 8,9,10). The photospheric carbon in all six systems has been detected in optical spectra. These rare objects have effective temperatures ranging from 13,000 to 17,000 K and masses between 1.13 and 1.19 M⊙, placing them firmly on the Q-branch (Fig. 1). Their observed atmospheric compositions can only be accounted for by extremely thin hydrogen and helium layers, where underlying carbon is dredged up by a superficial convection zone11,12. The thin hydrogen and helium layers, coupled with the large space velocity dispersions, strongly suggest a merger origin8,9.

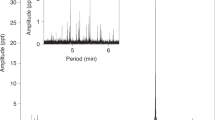

Investigating the photospheric metal features present in the far-UV spectra of 311 hydrogen-atmosphere white dwarfs observed with the Cosmic Origin Spectrograph (COS) onboard the Hubble Space Telescope (HST)13, we detected photospheric carbon in WD 0525+526, a white dwarf located at the high-mass end of the Q-branch (Fig. 1). In addition to the broad Lyman α absorption in the spectrum confirming the atmosphere’s hydrogen-dominated nature14, WD 0525+526 exhibits strong absorption lines of atomic carbon (Fig. 2). The strongest carbon transitions are C ii at 1,334 and 1,335 Å, which are blended with absorption arising from the interstellar medium (ISM) along the line of sight. However, the presence of higher-order atomic transitions of carbon (C iii multiplet at 1,174–1,177 ) confirms that the red-shifted C ii lines at 92.8 km s−1 are of photospheric origin.

The observed spectrum is shown in grey, with the best-fit model in red. The broad Lyman α absorption corroborates the hydrogen-rich atmosphere of WD 0525+526. Multiple narrow absorption lines of carbon are detected. The stronger transitions of carbon included in the fit are indicated by solid blue lines, and weaker ones or those with inaccurate atomic data that were excluded from the fit are shown by dashed green lines. The best-fit parameters obtained from the model fit are listed where g is the surface gravity of the white dwarf. The insets provide close-ups of the C iii (left) and C ii (right) lines that were used to determine the photospheric carbon abundance. The strongest C ii lines were used to determine the radial velocity of the white dwarf, which is +92.8 ± 0.6 km s−1. The black curves show the best-fit Gaussian profiles to the carbon absorption features originating from interstellar clouds (indicated by solid black lines) traversing at an average velocity of +18.7 ± 1.1 km s−1 along the line of sight, which is consistent with the predicted velocity of absorption (~19.1 km s−1) from the local ISM69.

By fitting white dwarf atmospheric models15 to the flux-calibrated COS spectrum and the Gaia parallax13 and using a mass–radius relation5, we found an effective temperature of 20,820 ± 96 K and a mass of 1.20 ± 0.01 M⊙, confirming the white dwarf’s ultra-massive nature. Our parameters are consistent within ~3σ with the values reported from optical observations14,16,17. Keeping the white dwarf temperature and mass fixed, we modelled the carbon absorption lines with atmospheric models including the contribution of the interstellar lines and convolved with the COS line-spread function to derive a photospheric abundance of log(C/H) = –4.62 ± 0.04. The best-fitting model is shown in Fig. 2, and the white dwarf parameters are provided in Table 1. We retrieved the optical spectrum of WD 0525+526 (ref. 14) from the Montreal White Dwarf Database18; neither helium nor carbon lines were detected, yielding upper limits of log(He/H) < –1.66 and log(C/H) < –1.91 (both 99% confidence; Extended Data Fig. 1).

We conclude that WD 0525+526 is part of the small class of DAQ white dwarfs9, among which it is the hottest and nearest (distance = 39.1 ± 0.08 pc; ref. 19) member. It also has the lowest carbon abundance, ≃4–5 dex lower than that of the six cooler DAQ stars (Fig. 1). The detection of carbon in WD 0525+526 was only possible because of the COS spectroscopy available for this star. Whereas metal transitions in the optical become weaker with increasing temperature, the far-UV is rich in strong metal lines20, allowing the detection of small amounts of photospheric metals. The identification of WD 0525+526 as a DAQ among ≃20 white dwarfs with masses >1.1 M⊙ in the ≃1,000-strong spectroscopically complete 40-pc sample21 suggests that atmospheric carbon pollution of hot ultra-massive hydrogen-rich white dwarfs may be relatively common.

The previously published DAQ white dwarfs are thought to have a convective envelope in which the elements are homogeneously mixed, indicating that the detected carbon has been dredged up from the interior8,9. In contrast, the hot hydrogen-dominated atmosphere of WD 0525+526 is expected to be stable to convection22. This suggests a stratified structure in which an extremely thin hydrogen-rich layer floats atop a carbon-rich envelope, the latter providing the detected atmospheric carbon through upward chemical diffusion. However, this interpretation seems to lead to a contradiction: the carbon-rich envelope should be convective23 and the overshooting flows should efficiently mix carbon up to the surface24, thereby precluding the existence of a hydrogen-rich atmosphere.

To gain further insight into this conundrum, we modelled the distribution of the chemical elements as a function of depth in the envelope of WD 0525+526 using the STELUM code25. In what follows, the radial chemical profile is expressed as the elemental abundances as a function of logarithmic mass depth, logq ≡ log(1 − mr/MWD) (where mr denotes the mass within radius r and MWD the total mass of the white dwarf). We computed a static envelope model with a self-consistent chemical profile obtained by considering atomic diffusion and convective mixing in equilibrium. We assumed the atmospheric parameters inferred above, including surface abundances log(He/H) = −1.66 and log(C/H) = −4.62. We computed the chemical profile from the atmosphere inwards by either integrating the diffusive equilibrium equations in convectively stable regions or imposing complete mixing in convectively unstable regions12, initially ignoring convective overshoot. Under these assumptions, the observed surface composition uniquely determines the entire envelope composition (Methods).

Our model (Fig. 3) confirms that the atmosphere of WD 0525+526 is not convective, allowing a thin hydrogen–helium shell to float on the surface and thus accounting for the low photospheric carbon abundance compared with the cooler DAQ stars. As anticipated, some convective mixing does occur just below the atmosphere (logq between about −15 and −16, shaded in blue in Fig. 3), but we found that this is inefficient mixing owing to semi-convection, rather than the usual efficient mixing associated with regular convection. Semi-convection occurs when a convective instability is strongly inhibited by a composition gradient (here, the hydrogen abundance gradient), leading to partial (rather than complete) mixing26. Although we did not include semi-convection explicitly in our modelling, it arises naturally in the form of alternating convective and non-convective layers in this region. The net result is that the slope of the abundance profiles falls between the limiting cases of diffusive equilibrium (steeper profiles) and uniform mixing (flat profiles), which is the signature of semi-convection26 (Methods and Extended Data Fig. 2). The occurrence of this process in white dwarfs with extremely thin hydrogen shells was suggested in 200727,28, but here it is formally predicted in a detailed envelope model.

The radial chemical profile of the model envelopes is expressed as the elemental mass fractions (Xi, for element i) as a function of logq ≡ log(1 − mr/MWD). a, Chemical profile of the hot DAQ WD 0525+526 assuming the atmospheric parameters determined from UV spectroscopy (Fig. 2). b, The same as a but with emphasis on the outermost layers. c, Chemical profile of the cooler DAQ WD J2340−1819 assuming the atmospheric parameters9 Teff = 15,836 K, logg = 8.95 and log(C/H) = +0.36, which are representative of the six known DAQ white dwarfs. d, The same as c but with emphasis on the outermost layers. In all panels, normal convection zones are shaded in grey, while semi-convection zones are shaded in blue. In the case of WD 0525+526, the normal convection zone with a uniform composition is much smaller, and there is a semi-convection zone showing a composition gradient near the surface. We used photospheric helium abundances corresponding to the upper limits determined from optical spectroscopy The legend in c applies to all panels.

We note that a standard carbon-driven convection zone23 generates additional mixing in a deeper region of the envelope (logq between about −10 and − 12, shaded in grey in Fig. 3). As a final step, we refined our model by including convective overshoot over one pressure scale height above and below this convection zone24, thereby slightly extending the mixed region (this is the final model shown in Fig. 3). We did not include overshoot beyond the semi-convection zone, as appropriate for such weakened convective flows. We performed a test calculation where we imposed a uniform composition in the semi-convective region, as would be expected for efficient mixing from regular convection and overshoot, and found that the resulting model is physically inconsistent (Methods and Extended Data Fig. 3). We interpret the outcome of this test as strong evidence for inefficient mixing owing to semi-convection in WD 0525+526, which effectively solves the apparent contradiction described earlier. Given that we could determine only an upper limit on the photospheric helium abundance, we also computed an envelope model without any helium, which yielded a similar chemical profile (Extended Data Fig. 4).

The total mass of hydrogen contained in our model of WD 0525+526 is 10−13.8 MWD. Similarly, the upper limit on the total mass of helium (that is, assuming the maximum surface abundance allowed by the observations) is 10−12.6 MWD. Both values are many orders of magnitude lower than expected from single-star evolution29 and thus indicative of a merger history, where thermonuclear burning during and after the merger event has depleted the hydrogen and helium contents6,30. For comparison, we also computed an envelope structure representative of the cooler and less massive DAQ stars (using the atmospheric parameters of WD J2340−1819 (ref. 9) as a typical example; Fig. 3), which yielded a homogeneous outer chemical profile8 (logq ≲ −10), as expected. The total hydrogen and helium masses of this model are 10−10.6 MWD and 10−9.3 MWD, respectively. Therefore, WD 0525+526 is not only hotter and more massive than other DAQ stars, but also seems to have much lower residual hydrogen and helium contents. This indicates that higher-mass mergers may lead to more severe hydrogen and helium deficiencies.

We reviewed alternative scenarios that could account for the peculiar atmospheric composition of WD 0525+526 and found that none of them is compelling (Methods), leaving a merger as the most plausible explanation. Furthermore, the merger interpretation is independently supported by the location of WD 0525+526 and other DAQ stars on the Gaia Q-branch. Previous studies have shown that the delayed ultra-massive white dwarfs forming the Q-branch must have carbon–oxygen cores5,31. As massive single-star evolution produces white dwarfs with oxygen–neon cores32 (albeit with possible exceptions30), these objects are probably merger products6,33.

To better constrain the merger scenario, we investigated the three-dimensional space motions of WD 0525+526. The line-of-sight velocity determined from carbon lines in the UV spectrum is +92.8 ± 0.6 km s−1. Correcting for the gravitational redshift of 141.4 km s−1, based on the measured stellar mass and radius (Table 1), results in a radial velocity of −48.6 ± 0.6 km s−1. Combined with the Gaia proper motions, the Galactic space velocities are (U,V,W) = (− 8.1,−117.9,1.2) km s−1, corrected to the local standard of rest34. While kinematical ages are only constrained via velocity dispersions of statistical samples, the total space velocity of WD 0525+526 is unusually high for stars in the local volume35, including white dwarfs36, and notably lags behind Galactic rotation. Given that single stars cannot be assigned to any population with absolute confidence, the relevant probabilities (that is, whether a given star belongs to a thin disk, thick disk or stellar halo) suggest that WD 0525+526 is a thick disk star; it is 280 times more likely to belong to the thick disk population than the halo population37. This is nevertheless consistent with a star that can be as old as the disk itself, and also compatible with the other members of the DAQ spectral class9. Because the estimated total age under the assumption of single-star evolution is well under 1 Gyr (ref. 38), the space velocity supports a merger origin.

In its past evolution, WD 0525+526 probably exhibited an extremely hot, carbon-dominated atmosphere similar to that of the well-studied massive pre-white dwarf H1504+65 (ref. 39). The star then cooled down and atomic diffusion began to operate, causing residual hydrogen to float towards the surface40,41 and form the thin hydrogen-dominated, carbon-polluted layer that we observe today. As WD 0525+526 cools further, it will develop efficient convection in its outer envelope, thoroughly diluting the thin hydrogen layer and dredging considerable carbon back to the surface, and will therefore turn into a DQ-type white dwarf9,12. However, this transformation may not take place for several billion years, as the current cooling of WD 0525+526 is probably slowed down by the energy release of the 22Ne distillation process5. Our study highlights that only UV spectroscopy may be capable of identifying hotter DAQ merger remnants, thereby improving our understanding of this important channel of binary evolution.

Methods

Optical spectroscopy

In an attempt to better constrain the upper limit on the photospheric helium abundance, we acquired optical spectroscopy with the Binospec spectrograph42 at the MMT Observatory as part of our programme of spectroscopic follow-up of white dwarfs in the solar neighbourhood (PI: T.C.). The MMT/Binospec observations were carried out in September 2024, making use of the long slit with a width of 1 arcsec. We adopted the LP3500 filter, a grating with 1,000 lines per millimetre and a central wavelength of 4,500 Å. This set-up offered sensitivity at wavelengths ranging from 3,800–5,200 Å with a spectral resolution of R ≈ 3,900. Our observations consist of three consecutive exposures with individual exposure times of 1,200 s, yielding a total exposure time of 60 min. The Binospec data were reduced using the official IDL pipeline43. We determined the helium and carbon upper limits following the same procedure explained in Extended Data Fig. 1. The upper limits (log(He/H) < −1.5 and log(C/H) < −2.3 at 99% confidence) were found to be consistent with those based on the optical spectrum14 available from the Montreal White Dwarf Database.

Envelope modelling

We used the STELUM code25 to compute static envelope models for WD 0525+526. We developed and exploited a new capability to produce equilibrium models in which the thermodynamic structure and chemical profile account for diffusion and convection in a self-consistent way. Such static equilibrium models are appropriate for our purpose given that the diffusive and convective timescales are both much shorter than the evolutionary timescale in the outer layers of white dwarfs44,45. We first obtained an approximate initial model by solving the stellar structure equations for a uniform composition (that is, imposing the measured surface abundances everywhere in the envelope). Holding the thermodynamic structure fixed, we then computed a detailed chemical profile, starting from the base of the atmosphere (Rosseland optical depth of 100, corresponding to logq ≃ −16.2) and proceeding inwards grid point by grid point. For convectively stable grid points, we determined the elemental abundances by integrating the diffusive equilibrium equations12. For convectively unstable grid points, we assumed complete mixing and thus set the same composition as the grid point immediately above. We treated convection using the Schwarzschild criterion and the ML2 version of the mixing-length theory46. The new chemical profile was then used to update the thermodynamic structure (and hence convective region), which in turn was used to recompute the chemical profile, with further iterations until convergence on a fully consistent model. The envelope integrations were performed down to logq = −3.0, which is located well inside the pure-carbon region.

We computed models for two possible atmospheric compositions, one with helium at the estimated upper limit and one without any helium. These two assumptions led to qualitatively similar chemical profiles (shown in Fig. 3 and Extended Data Fig. 4, respectively), and thus we focus hereafter on the model with helium. A convection zone is present at −12 ≲ logq ≲ −10 owing to the partial K-shell ionization of carbon23, producing flat abundance profiles. Convection also arises closer to the atmosphere at −16 ≲ logq ≲ −15 owing to the partial L-shell ionization of helium and carbon23,47, but in this case the convective grid points are interspersed with non-convective grid points, resulting in non-zero abundance gradients. We interpret this behaviour as the manifestation of semi-convection26 in our simple equilibrium model.

To support our interpretation, Extended Data Fig. 2 displays the radial profiles of key physical quantities in the region of interest; the panels show, from top to bottom, the hydrogen mass fraction XH, the difference between the radiative and adiabatic temperature gradients, ∇rad − ∇ad, and the ratio of convective to total energy flux, Fconv/Ftot. For purely illustrative purposes, we first discuss a low-resolution model with only ≃35 grid points in the range −16 ≲ logq ≲ −15, shown as blue circles. Each grid point is depicted either as a filled symbol if it is convectively stable (∇rad − ∇ad < 0, Fconv/Ftot = 0) or as an empty symbol if it is convectively unstable (∇rad − ∇ad > 0, Fconv/Ftot > 0). At logq ≲ −15.9, the envelope is stable, so the hydrogen abundance decreases inwards as a result of diffusive equilibrium. The gradual enrichment in partially ionized helium and carbon (at the expense of fully ionized hydrogen) causes an increase in radiative opacity and thus in ∇rad. At some point, the latter becomes larger than ∇ad, implying that the plasma at this depth is convective and therefore that the composition remains constant on the next underlying grid points, given our assumption that convection generates uniform mixing. Proceeding farther inwards, the increase in temperature at constant composition translates into a gradual decrease in opacity and ∇rad (a well-known feature of stellar envelopes). The latter eventually drops back below ∇ad, so the corresponding grid point is convectively stable and the composition is once again allowed to vary following diffusive equilibrium. However, the decrease in hydrogen abundance over the next grid point immediately restores the condition of convective instability and thus chemical mixing. This pattern of alternating convective and non-convective layers repeats itself until logq ≃ −14.9, where the hydrogen content becomes too low to notably affect the opacity. From this point inwards, ∇rad monotonically decreases and thus the plasma remains stable.

The net result of these oscillations in ∇rad − ∇ad around 0 is a staircase-like chemical profile, with small discontinuities at non-convective grid points. These discontinuities are probably not physical: they are due to the finite number of grid points in our model as well as our assumption of complete mixing in convective regions. The latter hypothesis is probably inappropriate here given that the plasma is just on the edge between stability and instability. The same can be said of the blind use of the mixing-length formalism to calculate the convective flux and velocity, which abruptly vanish at non-convective grid points given the strictly local nature of the theory. Still, the emergence of a staircase-like chemical profile is informative as it constitutes a well-known signature of semi-convection in one-dimensional stellar models48,49 and even in three-dimensional hydrodynamical simulations50. To better capture the true chemical profile, we computed models with higher grid resolutions and found that the discontinuities became smaller as the number of grid points was increased. A model with ≃100 grid points in the region of interest, a threefold increase in resolution compared with the illustrative model discussed above, is displayed as red diamonds in Extended Data Fig. 2. To remove the remaining unphysical discontinuities, the abundance profiles of this model were smoothed by imposing strict convective neutrality, ∇rad = ∇ad, resulting in the black lines in Extended Data Fig. 2. This corresponds to our adopted chemical profile, shown in Fig. 3 (and similarly in Extended Data Fig. 4 for the helium-free case). The outcome is a mild, continuous composition gradient in this region, intermediate between the much steeper gradient expected for pure diffusive equilibrium and the perfectly flat gradient expected for efficient convective mixing.

To further demonstrate that this is the sole physically viable solution, we performed numerical experiments where we forced the chemical profile in the region of interest to follow either one of the two limiting cases. These artificial models are shown in Extended Data Fig. 3, which is identical in format to Extended Data Fig. 2; the blue circles and red diamonds denote the cases of imposed diffusive equilibrium and uniform mixing, respectively. In the model assuming diffusive equilibrium, the hydrogen abundance sharply decreases inwards, such that ∇rad becomes much larger than ∇ad, accordingly generating a convection zone that transports over 90% of the total energy flux. Such a vigorous convection zone should completely mix the various elements, and hence this model is clearly inconsistent. In the model assuming a uniform composition, the large hydrogen abundance causes ∇rad to remain smaller than ∇ad and thus entirely suppresses the convective instability, again leading to a contradiction. Therefore, the only self-consistent solution is an intermediate composition gradient such that the equality ∇rad = ∇ad is strictly satisfied, as in our adopted model. The physical interpretation is that this region experiences semi-convection: weak convective flows inducing just enough mixing to maintain convective neutrality26. This is a self-regulating process, as any deviation towards stronger or weaker mixing would drive the system back to equilibrium, thus leading to a unique chemical profile.

Finally, we note that our test where uniform mixing was imposed effectively rules out the possibility of mixing due to overshoot beyond the semi-convective zone. Indeed, adding overshoot in our model would shift the boundary of the mixed region closer to the surface and thus increase the hydrogen abundance in that region. This would in turn push the model farther from the condition of convective instability, worsening the contradiction described above. Therefore, we conclude that overshoot is negligible in this case, in line with the idea that fluid motions arising from semi-convection are considerably weaker than those characterizing normal convection. This justifies our choice to include overshoot solely beyond the standard convection zone at −12 ≲ logq ≲ −10.

In our envelope calculations, we placed the outer boundary at Rosseland optical depth of 100 corresponding to logq ≃ −16.2, implying that we imposed a uniform composition above that point, as can be seen in Fig. 3. We made this choice for consistency with the atmosphere models used in the spectroscopic analysis, which assume a homogeneous chemical mixture15. In reality, since the atmosphere is radiative, diffusion is expected to operate all the way out to the surface. To verify that the presence of the semi-convection zone is robust to this assumption, we also computed envelope models with outer boundaries at lower optical depths. We found that such models still contained a semi-convective region of similar extent, the only difference being that this region was slightly shifted upwards (approximately following Δlogτ ≈ Δlogq, where τ denotes the optical depth). Therefore, we conclude that this numerical parameter does not affect our conclusion regarding the occurrence of semi-convection in WD 0525+526. An improved analysis would require atmosphere models that similarly take diffusion into account and thus allow a stratified chemical profile51,52, but such models currently do not exist for hydrogen–carbon compositions and their development is beyond the scope of this Article.

Alternative scenarios for the atmospheric composition

We interpreted the hydrogen-dominated, carbon-polluted atmosphere of WD 0525+526 as the result of severe hydrogen and helium deficiencies arising from a past stellar merger. In addition to this interpretation, we explored other scenarios that could potentially account for the photospheric carbon abundance observed in WD 0525+526.

The process of radiative levitation can support heavy elements (including carbon) at the surface of hot white dwarfs with Teff ≳ 20,000 K (ref. 53). However, this mechanism is predicted to be ineffective at the relatively low temperature and very high surface gravity of WD 0525+526 (refs. 54,55).

Another possible source of photospheric carbon is accretion of material from the ISM56, a disrupted planetary system54 or a close (sub)stellar companion57. However, in all cases, other heavy elements would be detected alongside carbon in the UV spectrum of the white dwarf. In the case of planetary debris with a standard rocky composition (such as bulk Earth), silicon would be the most noticeable element. In the case of a volatile-rich object (such as a comet), other elements such as nitrogen, phosphorus and sulfur would be observed. For accretion from the ISM or a companion, all these species may be present. We did not detect photospheric silicon or any heavy element other than carbon in the COS spectrum of WD 0525+526. From the absence of the Si ii doublet near 1,265 Å, we measured an upper limit of log(Si/H) < −8.5, implying a C/Si ratio ≳3 orders of magnitude higher than that typically produced by accretion54. Furthermore, we searched for infrared excess and photometric variability that would indicate the presence of a debris disk or a close companion. We built the spectral energy distribution of WD 0525+526 using available optical and infrared photometry, including Gaia G − GBP − GRP19, Panoramic Survey Telescope and Rapid Response System (Pan-STARRS) grizy58, and Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) W159. We did not detect any anomalous excess in the WISE W1 band. We looked for photometric variability using Zwicky Transient Facility60 and Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite61 observations. We found that WD 0525+526 is not variable on timescales of a few minutes to several hours, with variability limits of at least 0.5% in Zwicky Transient Facility DR20 and 0.4% from about three months (Sectors 19, 59, and 73) of 2-min-cadence data from the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite. Therefore, all variants of the accretion scenario seem highly unlikely.

Many cool white dwarfs with Teff ≲ 10,000 K exhibit a helium-dominated, carbon-polluted atmosphere7,62 ascribed to dredge-up of internal carbon by a helium-driven convection zone63,64. These objects are believed to originate from single-star evolution involving a so-called late helium-shell flash, a phenomenon that drastically reduces the hydrogen content while leaving the helium content largely intact63,65. The carbon dredge-up process requires a deep convection zone and thus usually occurs at effective temperatures lower than that of WD 0525+526. There are a few exceptions, notably a handful of helium-rich white dwarfs with temperatures (Teff ≃ 22,000–26,000 K) and carbon abundances (log(C/H) ≃ −5.5) similar to those of WD 0525+526 (while being devoid of other heavy elements)66,67. The cause of the carbon pollution in these stars is still debated but has been tentatively attributed to convective dredge-up67. In any case, these objects are notably different from the DAQ white dwarfs, as they have typical masses (~0.6 M⊙ on average) and helium-dominated atmospheres, and therefore they probably have a distinct origin68.

Data availability

The COS spectra of WD 0525+526 are publicly available in the MAST HST archive (https://mast.stsci.edu/search/ui/#/hst) under programme ID 15073. The MMT/Binospec spectrum, best-fitting model spectrum and chemical profile are provided in Supplementary Data 1–6.

References

Gaia Collaboration Gaia Data Release 2. Summary of the contents and survey properties. Astron. Astrophys. 616, A1 (2018).

Tremblay, P.-E. et al. Core crystallization and pile-up in the cooling sequence of evolving white dwarfs. Nature 565, 202–205 (2019).

Cheng, S., Cummings, J. D. & Ménard, B. A cooling anomaly of high-mass white dwarfs. Astrophys. J. 886, 100 (2019).

Blouin, S., Daligault, J. & Saumon, D. 22Ne phase separation as a solution to the ultramassive white dwarf cooling anomaly. Astrophys. J. Lett. 911, L5 (2021).

Bédard, A., Blouin, S. & Cheng, S. Buoyant crystals halt the cooling of white dwarf stars. Nature 627, 286–288 (2024).

Shen, K. J., Blouin, S. & Breivik, K. The Q branch cooling anomaly can be explained by mergers of white dwarfs and subgiant stars. Astrophys. J. Lett. 955, L33 (2023).

Coutu, S. et al. Analysis of helium-rich white dwarfs polluted by heavy elements in the Gaia era. Astrophys. J. 885, 74 (2019).

Hollands, M. A. et al. An ultra-massive white dwarf with a mixed hydrogen-carbon atmosphere as a likely merger remnant. Nat. Astron. 4, 663–669 (2020).

Kilic, M. et al. White dwarf merger remnants: the DAQ subclass. Astrophys. J. 965, 159 (2024).

Jewett, G. et al. Massive white dwarfs in the 100 pc sample: magnetism, rotation, pulsations, and the merger fraction. Astrophys. J. 974, 12 (2024).

Althaus, L. G., García-Berro, E., Córsico, A. H., Miller Bertolami, M. M. & Romero, A. D. On the formation of hot DQ white dwarfs. Astrophys. J. Lett. 693, L23–L26 (2009).

Koester, D., Kepler, S. O. & Irwin, A. W. New white dwarf envelope models and diffusion. Application to DQ white dwarfs. Astron. Astrophys. 635, A103 (2020).

Sahu, S. et al. An HST COS ultraviolet spectroscopic survey of 311 DA white dwarfs – I. Fundamental parameters and comparative studies. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 526, 5800–5823 (2023).

Gianninas, A., Bergeron, P. & Ruiz, M. T. A spectroscopic survey and analysis of bright, hydrogen-rich white dwarfs. Astrophys. J. 743, 138 (2011).

Koester, D. White dwarf spectra and atmosphere models. Mem. Soc. Astron. Ital. 81, 921–931 (2010).

McCleery, J. et al. Gaia white dwarfs within 40 pc II: the volume-limited northern hemisphere sample. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 499, 1890–1908 (2020).

Gentile Fusillo, N. P. et al. A catalogue of white dwarfs in Gaia EDR3. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 508, 3877–3896 (2021).

Dufour P. et al. 20th European White Dwarf Workshop. in Astronomical Society of the Pacific Conference Series (eds Tremblay P. E. et al.) Vol. 509, 3 (2017).

Gaia Collaboration Gaia Data Release 3. Summary of the content and survey properties. Astron. Astrophys. 674, A1 (2023).

Gänsicke, B. T. et al. The chemical diversity of exo-terrestrial planetary debris around white dwarfs. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 424, 333–347 (2012).

O’Brien, M. W. et al. The 40 pc sample of white dwarfs from Gaia. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 527, 8687–8705 (2024).

Tremblay, P. E. et al. Calibration of the mixing-length theory for convective white dwarf envelopes. Astrophys. J. 799, 142 (2015).

Saumon, D., Blouin, S. & Tremblay, P.-E. Current challenges in the physics of white dwarf stars. Phys. Rep. 988, 1–63 (2022).

Cunningham, T., Tremblay, P.-E., Freytag, B., Ludwig, H.-G. & Koester, D. Convective overshoot and macroscopic diffusion in pure-hydrogen-atmosphere white dwarfs. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 488, 2503–2522 (2019).

Bédard, A., Brassard, P., Bergeron, P. & Blouin, S. On the spectral evolution of hot white dwarf stars. II. Time-dependent simulations of element transport in evolving white dwarfs with STELUM. Astrophys. J. 927, 128 (2022).

Salaris, M. & Cassisi, S. Chemical element transport in stellar evolution models. R. Soc. Open Sci. 4, 170192 (2017).

Shibahashi, H. The DB Gap and Pulsations of White Dwarfs. In Unsolved Problems in Stellar Physics: A Conference in Honor of Douglas Gough AIP Conference Series Vol. 948 (eds Stancliffe, R. J. et al.) 35–42 (AIP, 2007).

Kurtz, D. W., Shibahashi, H., Dhillon, V. S., Marsh, T. R. & Littlefair, S. P. A search for a new class of pulsating DA white dwarf stars in the DB gap. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 389, 1771–1779 (2008).

Renedo, I. et al. New cooling sequences for old white dwarfs. Astrophys. J. 717, 183–195 (2010).

Althaus, L. G. et al. The formation of ultra-massive carbon-oxygen core white dwarfs and their evolutionary and pulsational properties. Astron. Astrophys. 646, A30 (2021).

Bauer, E. B., Schwab, J., Bildsten, L. & Cheng, S. Multi-gigayear white dwarf cooling delays from clustering-enhanced gravitational sedimentation. Astrophys. J. 902, 93 (2020).

Camisassa, M. E. et al. The evolution of ultra-massive white dwarfs. Astron. Astrophys. 625, A87 (2019).

Wu, C., Xiong, H. & Wang, X. Formation of ultra-massive carbon-oxygen white dwarfs from the merger of carbon-oxygen and helium white dwarf pairs. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 512, 2972–2987 (2022).

Coşkunoglu, B. et al. Local stellar kinematics from RAVE data – I. Local standard of rest. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 412, 1237–1245 (2011).

Nordström, B. et al. The Geneva-Copenhagen survey of the solar neighbourhood. Ages, metallicities, and kinematic properties of ~14 000 F and G dwarfs. Astron. Astrophys. 418, 989–1019 (2004).

Raddi, R. et al. Kinematic properties of white dwarfs. Galactic orbital parameters and age-velocity dispersion relation. Astron. Astrophys. 658, A22 (2022).

Bensby, T., Feltzing, S. & Oey, M. S. Exploring the Milky Way stellar disk. A detailed elemental abundance study of 714 F and G dwarf stars in the solar neighbourhood. Astron. Astrophys. 562, A71 (2014).

Bédard, A., Bergeron, P., Brassard, P. & Fontaine, G. On the spectral evolution of hot white dwarf stars. I. A detailed model atmosphere analysis of hot white dwarfs from SDSS DR12. Astrophys. J. 901, 93 (2020).

Werner, K. & Rauch, T. Analysis of HST/COS spectra of the bare C-O stellar core H1504+65 and a high-velocity twin in the Galactic halo. Astron. Astrophys. 584, A19 (2015).

Althaus, L. G., Miller Bertolami, M. M., Córsico, A. H., García-Berro, E. & Gil-Pons, P. The formation of DA white dwarfs with thin hydrogen envelopes. Astron. Astrophys. 440, L1–L4 (2005).

Bédard, A., Bergeron, P. & Brassard, P. On the spectral evolution of hot white dwarf stars. IV. The diffusion and mixing of residual hydrogen in helium-rich white dwarfs. Astrophys. J. 946, 24 (2023).

Fabricant, D. et al. Binospec: a wide-field imaging spectrograph for the MMT. Publ. Astron. Soc. Pac. 131, 075004 (2019).

Kansky, J. et al. Binospec software system. Publ. Astron. Soc. Pac. 131, 075005 (2019).

Fontaine, G. & Michaud, G. Diffusion time scales in white dwarfs. Astrophys. J. 231, 826–840 (1979).

Koester, D. Accretion and diffusion in white dwarfs. New diffusion timescales and applications to GD 362 and G 29-38. Astron. Astrophys. 498, 517–525 (2009).

Tassoul, M., Fontaine, G. & Winget, D. E. Evolutionary models for pulsation studies of white dwarfs. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 72, 335 (1990).

Cukanovaite, E. et al. Calibration of the mixing-length theory for structures of helium-dominated atmosphere white dwarfs. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 490, 1010–1025 (2019).

Grossman, S. A. & Taam, R. E. Double-diffusive mixing-length theory, semiconvection and massive star evolution. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 283, 1165–1178 (1996).

Paxton, B. et al. Modules for Experiments in Stellar Astrophysics (MESA): convective boundaries, element diffusion, and massive star explosions. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 234, 34 (2018).

Wood, T. S., Garaud, P. & Stellmach, S. A new model for mixing by double-diffusive convection (semi-convection). II. The transport of heat and composition through layers. Astrophys. J. 768, 157 (2013).

Manseau, P. M., Bergeron, P. & Green, E. M. A spectroscopic search for chemically stratified white dwarfs in the Sloan Digital Sky Survey. Astrophys. J. 833, 127 (2016).

Bédard, A. & Tremblay, P.-E. The prototype double-faced white dwarf has a thin hydrogen layer across its entire surface. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 538, L69–L75 (2025).

Chayer, P., Fontaine, G. & Wesemael, F. Radiative levitation in hot white dwarfs: equilibrium theory. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 99, 189 (1995).

Koester, D., Gänsicke, B. T. & Farihi, J. The frequency of planetary debris around young white dwarfs. Astron. Astrophys. 566, A34 (2014).

Ould Rouis, L. B. et al. Constraints on remnant planetary systems as a function of main-sequence mass with HST/COS. Astrophys. J. 976, 156 (2024).

Dupuis, J., Fontaine, G., Pelletier, C. & Wesemael, F. A study of metal abundance patterns in cool white dwarfs. II. Simulations of accretion episodes. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 84, 73 (1993).

Wilson, D. J. et al. Discovery of a young pre-intermediate polar. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 508, 561–574 (2021).

Flewelling, H. A. et al. The Pan-STARRS1 database and data products. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 251, 7 (2020).

Wright, E. L. et al. The Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE): mission description and initial on-orbit performance. Astron. J. 140, 1868–1881 (2010).

Bellm, E. C. et al. The Zwicky Transient Facility: system overview, performance, and first results. Publ. Astron. Soc. Pac. 131, 018002 (2019).

Ricker, G. R. et al. Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS). J. Astron. Telesc. Instrum. Syst. 1, 014003 (2015).

Blouin, S., Bédard, A. & Tremblay, P.-E. Carbon dredge-up required to explain the Gaia white dwarf colour-magnitude bifurcation. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 523, 3363–3375 (2023).

Althaus, L. G. et al. The formation and evolution of hydrogen-deficient post-AGB white dwarfs: the emerging chemical profile and the expectations for the PG 1159-DB-DQ evolutionary connection. Astron. Astrophys. 435, 631–648 (2005).

Bédard, A., Bergeron, P. & Brassard, P. On the spectral evolution of hot white dwarf stars. III. The PG 1159-DO-DB-DQ evolutionary channel revisited. Astrophys. J. 930, 8 (2022).

Werner, K. & Herwig, F. The elemental abundances in bare planetary nebula central stars and the shell burning in AGB stars. Publ. Astron. Soc. Pac. 118, 183–204 (2006).

Petitclerc, N., Wesemael, F., Kruk, J. W., Chayer, P. & Billères, M. FUSE observations of DB white dwarfs. Astrophys. J. 624, 317–330 (2005).

Koester, D., Provencal, J. & Gänsicke, B. T. Atmospheric parameters and carbon abundance for hot DB white dwarfs. Astron. Astrophys. 568, A118 (2014).

Bédard, A. The spectral evolution of white dwarfs: where do we stand? Astrophys. Space Sci. 369, 43 (2024).

Redfield, S. & Linsky, J. L. The structure of the local interstellar medium. IV. Dynamics, morphology, physical properties, and implications of cloud-cloud interactions. Astrophys. J. 673, 283–314 (2008).

Acknowledgements

This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme through grant agreement numbers 101002408 (MOS100PC) and 101020057 (WDPLANETS). A.B. is a Postdoctoral Fellow of the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) of Canada. T.C. acknowledges support from NASA (National Aeronautics and Space Administration) through the NASA Hubble Fellowship grant HST-HF2-51527.001-A awarded by the Space Telescope Science Institute, which is operated by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, Inc., for NASA, under contract number NAS5-26555. This research is based on observations made with the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope obtained from the Space Telescope Science Institute, which is operated by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, Inc., under NASA contract number NAS 5-26555, associated with programme 15073. This work has made use of data from the European Space Agency (ESA) mission Gaia (https://www.cosmos.esa.int/gaia), processed by the Gaia Data Processing and Analysis Consortium (DPAC, https://www.cosmos.esa.int/web/gaia/dpac/consortium). Funding for the DPAC has been provided by national institutions, in particular, the institutions participating in the Gaia Multilateral Agreement. We acknowledge the University of Warwick’s Scientific Computing Research Technology Platform (SCRTP) for assistance in the research described in this article. Observations reported here were obtained at the MMT Observatory, a joint facility of the Smithsonian Institution and the University of Arizona. This article uses data products produced by the OIR Telescope Data Center (TDC), supported by the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory. The MMT/Binospec data were reduced by the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory TDC; we thank S. Moran and I. Chilingarian for their help with that work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the work presented in this paper. S.S. led the project and performed the spectral analysis. A.B. performed the envelope modelling. S.S. and A.B. wrote the majority of the paper. B.T.G. was the PI of the HST programme. B.T.G., P.-E.T., J.F. and J.J.H. helped with the interpretation of WD 0525+526 and the writing of the paper. D.K. calculated the atmospheric models used in the spectral analysis. M.A.H. helped with the analysis of optical spectra. T.C. acquired the MMT/Binospec spectrum. S.R. helped with the interpretation of interstellar absorption in the spectra.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Astronomy thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Optical upper limits on the helium and carbon abundances of WD 0525 + 526.

The left (a) and right (b) panels illustrate the upper limit determination for helium and carbon, respectively, using the optical spectroscopic data14 shown as solid black lines. The model spectra corresponding to the 99th percentile upper limits are over-plotted as solid red lines. To calculate the upper limits, we created a grid of models with helium abundances log(He/H) varying from − 4.0 to − 0.5 and carbon abundances log(C/H) from − 8.0 to − 1.0 in steps of 0.05. For helium, we selected the spectral region 4430–4510 Å which contains a strong absorption feature from the He i line at 4472.75 Å. For carbon, we chose the spectral region spanning 5115–5175 Å with the strongest C ii lines from 5134.38 Å to 5152.52 Å. Fixing the Teff, \(\log g\), and velocity to the best-fit values obtained from ultraviolet spectroscopy, the upper limits were determined following the same procedure as for a previously identified DAQ white dwarf8.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Properties of the semi-convective region in envelope models with different grid resolutions.

The top, middle, and bottom panels show the hydrogen mass fraction, the difference between the radiative and adiabatic temperature gradients, and the ratio of convective to total energy flux, respectively, as a function of logarithmic mass depth. Illustrative models with low and high grid resolutions (≃ 35 and 100 grid points in the region of interest) are displayed as blue circles and red diamonds, respectively. Each grid point is depicted as an individual symbol, with empty and filled symbols denoting convective and non-convective grid points, respectively. The solid black lines show our adopted model, which was obtained by adjusting the chemical profile of the high-resolution model to enforce ∇rad = ∇ad in the semi-convective region. In the middle panel, the dotted black line indicates ∇rad = ∇ad.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Properties of the semi-convective region in envelope models with imposed chemical profiles.

The top, middle, and bottom panels show the hydrogen mass fraction, the difference between the radiative and adiabatic temperature gradients, and the ratio of convective to total energy flux, respectively, as a function of logarithmic mass depth. Illustrative high-resolution models with imposed diffusive equilibrium and imposed uniform mixing in the semi-convective region are displayed as blue circles and red diamonds, respectively. Each grid point is depicted as an individual symbol, with empty and filled symbols denoting convective and non-convective grid points, respectively. The model assuming diffusive equilibrium is convectively unstable, while the model assuming uniform mixing is convectively stable, therefore both models are inconsistent. The solid black lines show our adopted model, which is the only self-consistent solution.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Envelope chemical structure of DAQ white dwarfs without any helium.

The radial chemical profile of the model envelopes is expressed as the run of the elemental mass fractions with logarithmic mass depth, \(\log q\equiv \log (1-{m}_{r}/{M}_{{\rm{WD}}})\). The top panels (a and b) show the chemical profile of the hot DAQ WD 0525 + 526 assuming the atmospheric parameters determined from ultraviolet spectroscopy (see Fig. 2). The bottom panels (c and d) show the chemical profile of the cooler DAQ WD J2340-1819 assuming the atmospheric parameters9Teff = 15 836 K, \(\log g=8.95\), and log(C/H) = + 0.36, which are representative of the six known DAQ white dwarfs. Normal convection zones are shaded in grey, while semi-convection zones are shaded in blue. These models do not include any photospheric helium.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Data 1

MMT/Binospec spectrum of WD 0525+526. Columns are: air wavelength (Å), flux (erg cm−2 s−1 Å−1), and flux error (erg cm−2 s−1 Å−1).

Supplementary Data 2

Best-fitting model spectrum for WD 0525+526 (Fig. 2) without convolution to COS spectral resolution. Columns are: vacuum wavelength (Å) and model flux (erg cm−2 s−1 Å−1).

Supplementary Data 3

Model envelope chemical profile of WD 0525+526 with helium at the upper limit (Fig. 3). Columns are: logarithm of mass depth (logq), logarithm of hydrogen (logH), helium (logHe) and carbon (logC) mass fractions, and a number indicating the presence and type of convective mixing, where 0 denotes no mixing, 1 denotes normal convection, 2 denotes overshoot and 3 denotes semi-convection.

Supplementary Data 4

Model envelope chemical profile of WD 0525+526 without any helium (Extended Data Fig. 4).

Supplementary Data 5

Model envelope chemical profile of WD J2340−1819 with helium at the upper limit (Fig. 3).

Supplementary Data 6

Model envelope chemical profile of WD J2340−1819 without any helium (Extended Data Fig. 4).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sahu, S., Bédard, A., Gänsicke, B.T. et al. A hot white dwarf merger remnant revealed by an ultraviolet detection of carbon. Nat Astron 9, 1347–1355 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-025-02590-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-025-02590-y