Abstract

Wolf–Rayet (WR) stars are the evolved descendants of the most massive stars and show emission-line-dominated spectra formed in their powerful winds. Marking the final stage before core collapse, the standard picture of WR stars has been that they evolve through three well-defined spectral subtypes known as WN, WC and WO. Here we present a detailed analysis of five objects that defy this scheme, demonstrating that WR stars can also evolve directly from the WN stage to the WO stage (WN/WO). Our study reveals that this direct transition is connected to low metallicity and weaker winds. The WN/WO stars and their immediate WN precursors are hot and emit a high flux of photons capable of fully ionizing helium. The existence of these stages unveils that high-mass stars that manage to shed off their outer hydrogen layers in a low-metallicity environment can spend a considerable fraction of their lifetime in a stage that is difficult to detect in integrated stellar populations, but at the same time yields a hard ionizing flux. The identification of the WN-to-WO evolution path for massive stars has significant implications for understanding the chemical enrichment and ionizing feedback in star-forming galaxies, in particular at earlier cosmic times.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All observational material employed in the current study is available publicly from the sources listed in ‘Observational data’ in Methods. The resulting synthetic spectra from the atmosphere models that support the findings of this study are plotted in the Extended Data figures. The raw model data are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Code availability

The standard branch of the PoWR atmosphere model code is described in refs. 16,17 and available at https://github.com/powr-code. The customized version by the corresponding author is described in refs. 1,18 and available on request. A brief conceptual overview is further given in ‘Stellar atmosphere modelling’ in Methods with the employed set of atomic data summarized in Extended Data Table 1.

References

Sander, A. A. C., Vink, J. S. & Hamann, W. R. Driving classical Wolf–Rayet winds: a Γ- and Z-dependent mass-loss. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 491, 4406–4425 (2020).

Smith, L. F., Shara, M. M. & Moffat, A. F. J. A three-dimensional classification for WN stars. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 281, 163–191 (1996).

Crowther, P. A., De Marco, O. & Barlow, M. J. Quantitative classification of WC and WO stars. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 296, 367–378 (1998).

Gamow, G. On WC and WN stars. Astrophys. J. 98, 500 (1943).

Langer, N. Wolf–Rayet stars of type WN/WC and mixing processes during core helium burning of massive stars? Astron. Astrophys. 248, 531 (1991).

Meynet, G., Maeder, A., Schaller, G., Schaerer, D. & Charbonnel, C. Grids of massive stars with high mass loss rates. V. From 12 to 120 Msun_ at Z=0.001, 0.004, 0.008, 0.020 and 0.040. Astron. Astrophys. Suppl. Ser. 103, 97–105 (1994).

Groh, J. H., Meynet, G., Ekström, S. & Georgy, C. The evolution of massive stars and their spectra. I. A non-rotating 60 M⊙ star from the zero-age main sequence to the pre-supernova stage. Astron. Astrophys. 564, A30 (2014).

Aadland, E. et al. WO-type Wolf–Rayet stars: the last hurrah of massive star evolution. Astrophys. J. 931, 157 (2022).

Massey, P. & Grove, K. The ‘WN+WC’ Wolf–Rayet stars MR 111 and GP Cep: spectrum binaries or missing links? Astrophys. J. 344, 870 (1989).

Crowther, P. A. Physical properties of Wolf–Rayet stars. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 45, 177–219 (2007).

Monreal-Ibero, A. et al. The Wolf–Rayet star population in the dwarf galaxy NGC 625. Astron. Astrophys. 603, A130 (2017).

Kehrig, C. et al. The extended He ii λ4686 emission in the extremely metal-poor galaxy SBS 0335 - 052E seen with MUSE. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 480, 1081–1095 (2018).

Mayya, Y. D. et al. Detection of He++ ion in the star-forming ring of the Cartwheel using MUSE data and ionizing mechanisms. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 519, 5492–5513 (2023).

Castellano, M. et al. JWST NIRSpec spectroscopy of the remarkable bright galaxy GHZ2/GLASS-z12 at redshift 12.34. Astrophys. J. 972, 143 (2024).

D’Eugenio, F. et al. JADES: carbon enrichment 350 Myr after the Big Bang. Astron. Astrophys. 689, A152 (2024).

Gräfener, G., Koesterke, L. & Hamann, W.-R. Line-blanketed model atmospheres for WR stars. Astron. Astrophys. 387, 244–257 (2002).

Sander, A. et al. On the consistent treatment of the quasi-hydrostatic layers in hot star atmospheres. Astron. Astrophys. 577, A13 (2015).

Sander, A. A. C. et al. The temperature dependency of Wolf–Rayet-type mass loss. An exploratory study for winds launched by the hot iron bump. Astron. Astrophys. 670, A83 (2023).

Hamann, W., Gräfener, G. & Liermann, A. The Galactic WN stars. Spectral analyses with line-blanketed model atmospheres versus stellar evolution models with and without rotation. Astron. Astrophys. 457, 1015–1031 (2006).

Lefever, R. R. et al. Exploring the influence of different velocity fields on Wolf–Rayet star spectra. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 521, 1374–1392 (2023).

Gräfener, G. & Vink, J. S. Stellar mass-loss near the Eddington limit. Tracing the sub-photospheric layers of classical Wolf–Rayet stars. Astron. Astrophys. 560, A6 (2013).

Grassitelli, L. et al. Subsonic structure and optically thick winds from Wolf–Rayet stars. Astron. Astrophys. 614, A86 (2018).

Hillier, D. J., Aadland, E., Massey, P. & Morrell, N. BAT99-9—a WC4 Wolf–Rayet star with nitrogen emission: evidence for binary evolution? Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 503, 2726–2732 (2021).

Tramper, F. et al. Massive stars on the verge of exploding: the properties of oxygen sequence Wolf–Rayet stars. Astron. Astrophys. 581, A110 (2015).

Langer, N. Standard models of Wolf–Rayet stars. Astron. Astrophys. 210, 93–113 (1989).

Eldridge, J. J. et al. Binary Population and Spectral Synthesis Version 2.1: construction, observational verification, and new results. Publ. Astron. Soc. Aust. 34, e058 (2017).

Eggenberger, P. et al. Grids of stellar models with rotation. VI. Models from 0.8 to 120 M⊙ at a metallicity Z = 0.006. Astron. Astrophys. 652, A137 (2021).

Vink, J. S. & de Koter, A. On the metallicity dependence of Wolf–Rayet winds. Astron. Astrophys. 442, 587–596 (2005).

Sander, A. A. C. & Vink, J. S. On the nature of massive helium star winds and Wolf–Rayet-type mass-loss. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 499, 873–892 (2020).

Woosley, S. E., Sukhbold, T. & Janka, H. T. The birth function for black holes and neutron stars in close binaries. Astrophys. J. 896, 56 (2020).

Maltsev, K. et al. Explodability criteria for the neutrino-driven supernova mechanism. Astron. Astrophys. 700, A20 (2025).

Garner, R. et al. NGC 628 in SIGNALS: explaining the abundance-ionization correlation in H ii regions. Astrophys. J. 978, 70 (2025).

Gunawardhana, M. L. P. et al. JADES NIRSpec Spectroscopy of GN-z11: evidence for Wolf–Rayet contribution to stellar populations at 430 Myr after Big Bang?. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 543, 3172–3195 (2025).

Schootemeijer, A. et al. An absence of binary companions to Wolf–Rayet stars in the Small Magellanic Cloud: implications for mass loss and black hole masses at low metallicities. Astron. Astrophys. 689, A157 (2024).

Kubátová, B. et al. Low-metallicity massive single stars with rotation. II. Predicting spectra and spectral classes of chemically homogeneously evolving stars. Astron. Astrophys. 623, A8 (2019).

Szécsi, D. et al. Low-metallicity massive single stars with rotation. III. Source of ionization and C-iv emission in I Zw 18. Astron. Astrophys. https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202452483 (2025).

Eldridge, J. J. & Stanway, E. R. New insights into the evolution of massive stars and their effects on our understanding of early galaxies. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 60, 455–494 (2022).

Shirazi, M. & Brinchmann, J. Strongly star forming galaxies in the local Universe with nebular He iiλ4686 emission. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 421, 1043–1063 (2012).

Morishita, T., Stiavelli, M., Schuldt, S. & Grillo, C. Dissecting the interstellar media of a Wolf–Rayet galaxy at z = 2.76. Astrophys. J. 979, 87 (2025).

Schaerer, D. On the properties of massive Population III stars and metal-free stellar populations. Astron. Astrophys. 382, 28–42 (2002).

Cleri, N. J. et al. CLEAR: high-ionization [Ne v] λ3426 emission-line galaxies at 1.4 < z < 2.3. Astrophys. J. 948, 112 (2023).

Doran, E. I. et al. The VLT-FLAMES Tarantula Survey. XI. A census of the hot luminous stars and their feedback in 30 Doradus. Astron. Astrophys. 558, A134 (2013).

Ramachandran, V. et al. Testing massive star evolution, star formation history, and feedback at low metallicity. Spectroscopic analysis of OB stars in the SMC Wing. Astron. Astrophys. 625, A104 (2019).

Ramachandran, V. et al. Stellar population of the superbubble N 206 in the LMC. II. Parameters of the OB and WR stars, and the total massive star feedback. Astron. Astrophys. 615, A40 (2018).

Neugent, K. F. & Massey, P. Newly discovered Wolf–Rayet stars in M31. Astron. J. 166, 68 (2023).

González-Torà, G. et al. SDSS-V LVM: detectability of Wolf–Rayet stars and their He ii ionizing flux in low-metallicity environments I. The weak-lined, early-type WN3 stars in the SMC. Astron. Astrophys. 703, L11 (2025).

Strom, A. L. et al. Nebular emission line ratios in z ≃ 2–3 star-forming galaxies with KBSS-MOSFIRE: exploring the impact of ionization, excitation, and nitrogen-to-oxygen ratio. Astrophys. J. 836, 164 (2017).

Tang, M. et al. JWST/NIRSpec spectroscopy of z = 7–9 star-forming galaxies with CEERS: new insight into bright Lyα emitters in ionized bubbles. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 526, 1657–1686 (2023).

Cameron, A. J. et al. Nebular dominated galaxies: insights into the stellar initial mass function at high redshift. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 534, 523–543 (2024).

Topping, M. W. et al. Deep rest-UV JWST/NIRSpec spectroscopy of early galaxies: the demographics of C iv and N-emitters in the reionization era. Astrophys. J. 980, 225 (2025).

Neugent, K. F. & Massey, P. The Wolf–Rayet content of M33. Astrophys. J. 733, 123 (2011).

Neugent, K. F., Massey, P. & Georgy, C. The Wolf–Rayet content of M31. Astrophys. J. 759, 11 (2012).

Sander, A., Todt, H., Hainich, R. & Hamann, W.-R. The Wolf–Rayet stars in M 31. I. Analysis of the late-type WN stars. Astron. Astrophys. 563, A89 (2014).

Shara, M. M. et al. The first transition Wolf–Rayet WN/C star in M31. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 455, 3453–3457 (2016).

Massey, P. et al. A survey of local group galaxies currently forming stars. I. UBVRI photometry of stars in M31 and M33. Astron. J. 131, 2478–2496 (2006).

Williams, B. F. et al. The Panchromatic Hubble Andromeda Treasury. X. Ultraviolet to infrared photometry of 117 million equidistant stars. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 215, 9 (2014).

Gaia Collaboration. VizieR Online Data Catalog: Gaia DR3 Part 1. Main Source (Gaia Collaboration, 2022); https://doi.org/10.26093/cds/vizier.1355

Cutri, R. M. et al. 2MASS All-Sky Catalog of Point Sources. VizieR https://vizier.u-strasbg.fr/viz-bin/cat/II/246 (2003).

Massey, P. Absolute spectrophotometry of northern Wolf–Rayet stars: how similarare the colors ? Astrophys. J. 281, 789–799 (1984).

Breysacher, J., Azzopardi, M. & Testor, G. The fourth catalogue of Population I Wolf–Rayet stars in the Large Magellanic Cloud. Astron. Astrophys. Suppl. Ser. 137, 117–145 (1999).

Neugent, K. F., Massey, P. & Morrell, N. A modern search for Wolf–Rayet stars in the Magellanic Clouds. IV. A final census. Astrophys. J. 863, 181 (2018).

Josiek, J., Ekström, S. & Sander, A. A. C. Impact of main sequence mass loss on the appearance, structure, and evolution of Wolf-Rayet stars. Astron. Astrophys. 688, A71 (2024).

Zhekov, S. A., Gagné, M. & Skinner, S. L. XMM-Newton observations reveal very high X-ray luminosity from the carbon-rich Wolf–Rayet star WR 48a. Astrophys. J. Lett. 727, L17 (2011).

Callingham, J. R. et al. Two Wolf–Rayet stars at the heart of colliding-wind binary Apep. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 495, 3323–3331 (2020).

Williams, B. F. et al. A deep XMM-Newton survey of M33: point-source catalog, source detection, and characterization of overlapping fields. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 218, 9 (2015).

Oskinova, L. M., Hamann, W. R., Feldmeier, A., Ignace, R. & Chu, Y. H. Discovery of X-ray emission from the Wolf–Rayet star WR 142 of oxygen subtype. Astrophys. J. Lett. 693, L44–L48 (2009).

Chené, A. N. et al. Investigating the origin of the spectral line profiles of the hot Wolf–Rayet star WR 2. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 484, 5834–5844 (2019).

Dsilva, K., Shenar, T., Sana, H. & Marchant, P. A spectroscopic multiplicity survey of Galactic Wolf–Rayet stars. II. The northern WNE sequence. Astron. Astrophys. 664, A93 (2022).

Pietrzyński, G. et al. A distance to the Large Magellanic Cloud that is precise to one per cent. Nature 567, 200–203 (2019).

Riess, A. G., Fliri, J. & Valls-Gabaud, D. Cepheid period–luminosity relations in the near-infrared and the distance to M31 from the Hubble Space Telescope Wide Field Camera 3. Astrophys. J. 745, 156 (2012).

Breuval, L. et al. A 1.3% distance to M33 from Hubble Space Telescope Cepheid photometry. Astrophys. J. 951, 118 (2023).

Hainich, R. et al. The Wolf–Rayet stars in the Large Magellanic Cloud. A comprehensive analysis of the WN class. Astron. Astrophys. 565, A27 (2014).

Bhattacharya, S. et al. The survey of planetary nebulae in Andromeda (M31)—IV. Radial oxygen and argon abundance gradients of the thin and thicker disc. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 517, 2343–2359 (2022).

Gräfener, G., Vink, J. S., de Koter, A. & Langer, N. The Eddington factor as the key to understand the winds of the most massive stars. Evidence for a Γ-dependence of Wolf-Rayet type mass loss. Astron. Astrophys. 535, A56 (2011).

Niemela, V. S., Barba, R. H. & Shara, M. M. in Wolf-Rayet Stars: Binaries; Colliding Winds; Evolution Vol. 163 of IAU Symposium (eds van der Hucht, K. A. & Williams, P. M.) 245–247 (Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1995).

Veen, P. M., van Genderen, A. M. & van der Hucht, K. A. The enigmatic WR46: a binary or a pulsator in disguise. III. Interpretation. Astron. Astrophys. 385, 619–631 (2002).

Hénault-Brunet, V. et al. New constraints on the origin of the short-term cyclical variability of the Wolf–Rayet star WR 46. Astrophys. J. 735, 13 (2011).

Gosset, E. et al. XMM-Newton observation of the enigmatic object WR 46. Astron. Astrophys. 527, A66 (2011).

Oskinova, L. M. Evolution of X-ray emission from young massive star clusters. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 361, 679–694 (2005).

Oskinova, L. M., Hamann, W., Feldmeier, A., Ignace, R. & Chu, Y. Discovery of X-ray emission from the Wolf–Rayet Star WR 142 of oxygen subtype. Astrophys. J. Lett. 693, L44–L48 (2009).

Crowther, P. A., Rate, G. & Bestenlehner, J. M. Line luminosities of Galactic and Magellanic Cloud Wolf–Rayet stars. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 521, 585–612 (2023).

Moens, N. et al. First 3D radiation-hydrodynamic simulations of Wolf–Rayet winds. Astron. Astrophys. 665, A42 (2022).

Crowther, P. A., Smith, L. J. & Hillier, D. J. Fundamental parameters of Wolf–Rayet stars. IV. Weak-lined WNE stars. Astron. Astrophys. 302, 457 (1995).

Boco, L. et al. Metal-poor single Wolf–Rayet stars: the interplay of optically thick winds and rotation. Astron. Astrophys. https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202556187 (2025).

Vink, J. S. & Harries, T. J. Wolf–Rayet spin at low metallicity and its implication for black hole formation channels. Astron. Astrophys. 603, A120 (2017).

Ekström, S. et al. Grids of stellar models with rotation. I. Models from 0.8 to 120 M⊙ at solar metallicity (Z = 0.014). Astron. Astrophys. 537, A146 (2012).

Crowther, P. A., Smith, L. J. & Willis, A. J. Fundamental parameters of Wolf–Rayet stars. V. The nature of the WN/C star WR 8. Astron. Astrophys. 304, 269 (1995).

Pauli, D., Langer, N., Aguilera-Dena, D. R., Wang, C. & Marchant, P. A synthetic population of Wolf–Rayet stars in the LMC based on detailed single and binary star evolution models. Astron. Astrophys. 667, A58 (2022).

Ramachandran, V. et al. Phase-resolved spectroscopic analysis of the eclipsing black hole X-ray binary M33 X-7: system properties, accretion, and evolution. Astron. Astrophys. 667, A77 (2022).

Rickard, M. J. et al. Stellar wind properties of the nearly complete sample of O stars in the low metallicity young star cluster NGC 346 in the SMC galaxy. Astron. Astrophys. 666, A189 (2022).

Crowther, P. A. & Hadfield, L. J. Reduced Wolf–Rayet line luminosities at low metallicity. Astron. Astrophys. 449, 711–722 (2006).

Kehrig, C. et al. The extended He ii λ4686-emitting region in IZw 18 unveiled: clues for peculiar ionizing sources. Astrophys. J. Lett. 801, L28 (2015).

Mingozzi, M. et al. Exploring the mysterious high-ionization source powering [Ne v] in high-z analog SBS0335-052 E with JWST/MIRI. Astrophys. J. 985, 253 (2025).

Nazé, Y., Rauw, G., Manfroid, J., Chu, Y. H. & Vreux, J. M. VLT observations of the highly ionized nebula around Brey2. Astron. Astrophys. 401, L13–L16 (2003).

Kewley, L. J., Dopita, M. A., Sutherland, R. S., Heisler, C. A. & Trevena, J. Theoretical modeling of starburst galaxies. Astrophys. J. 556, 121–140 (2001).

Kauffmann, G. et al. The host galaxies of active galactic nuclei. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 346, 1055–1077 (2003).

Crowther, P. A. & Castro, N. Mapping the core of the Tarantula Nebula with VLT-MUSE—III. A template for metal-poor starburst regions in the visual and far-ultraviolet. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 527, 9023–9047 (2024).

Micheva, G., Oey, M. S., Jaskot, A. E. & James, B. L. Mrk 71/NGC 2366: the nearest Green Pea analog. Astrophys. J. 845, 165 (2017).

Kehrig, C. et al. Gemini GMOS spectroscopy of Heii nebulae in M 33. Astron. Astrophys. 526, A128 (2011).

Yarovova, A. D., Egorov, O. V., Moiseev, A. V. & Maryeva, O. V. Unveiling the nitrogen-rich massive star in the metal-poor galaxy NGC 4068. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 518, 2256–2272 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This research is based on observations made with the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope obtained from the Space Telescope Science Institute, which is operated by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, Inc., under NASA contract NAS 5-26555. These observations are associated with programmes 15822 (principal investigator A.A.C.S.) and 17426 (principal investigator A.A.C.S.). This paper benefited from discussions at the International Space Science Institute (ISSI) in Bern through ISSI International Team project 512 (Multiwavelength View on Massive Stars in the Era of Multimessenger Astronomy, principal investigator L.M.O.). R.R.L. and J.J. are members of the International Max Planck Research School for Astronomy and Cosmic Physics at the University of Heidelberg (IMPRS-HD). A.A.C.S., R.R.L. and V.R. acknowledge support by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) in the form of an Emmy Noether Research Group – Project-ID 445674056 (SA4064/1-1, principal investigator A.A.C.S.). A.A.C.S. and V.R. further acknowledge support from the Deutsches Zentrum für Luft und Raumfahrt (DLR) grant grants 50 OR 2503 (principal investigator A.A.C.S.) and 50 OR 2306 (principal investigators V.R. and A.A.C.S.) as well as from the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) and the Baden-Württemberg Ministry of Science as part of the Excellence Strategy of the German Federal and State Governments. J.J. acknowledges funding from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) Project-ID 496854903 (SA4064/2-1, principal investigator A.A.C.S.). E.R.H. and J.S.V. are supported by STFC funding under grant number ST/V000233/1. L.M.O. acknowledges the funding provided by the DFG grant 443790621. D.P. acknowledges financial support by the Deutsches Zentrum für Luft und Raumfahrt (DLR) grant FKZ 50OR2005. R.H. acknowledges support from the World Premier International Research Centre Initiative (WPI Initiative), MEXT, Japan, the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (ChETEC-INFRA, Grant No. 101008324) and the IReNA AccelNet Network of Networks (National Science Foundation, Grant No. OISE-1927130). This article is based upon work from the ChETEC COST Action (CA16117). I.M. acknowledges support from the Australian Research Council (ARC) Centre of Excellence for Gravitational Wave Discovery (OzGrav), through project number CE230100016. This project was co-funded by the European Union (Project 101183150 - OCEANS).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.A.C.S. developed the hypothesis, developed the hydrodynamically consistent atmosphere PoWR code branch used in this work, calculated the final atmosphere models and wrote most of the paper. R.R.L. calculated the hydrodynamically consistent atmosphere models, performed the spectral re-classification and contributed to the paper. J.J. calculated the presented and related GENEC evolution models and contributed to the interpretation of the objects. E.R.H. provided WR star structure models and contributed to the discussion about their evolutionary nature. R.H. contributed to the paper, in particular with respect to the evolutionary interpretation and the discussion of the abundances. L.M.O. contributed the X-ray investigation of the studied targets and commented on the paper. D.P. calculated MESA evolution models, contributed to the discussion on the evolutionary status and commented on the paper. M.P. calculated early atmosphere models for one of the WN/WO targets. J.S.G. contributed to the paper and the discussion regarding the wider context of the targets. W.-R.H. developed the core and large parts of the PoWR atmosphere code and contributed to the discussion. I.M., V.R. and T.S. contributed to the discussion regarding the nature and impact of the studied objects. T.S. further contributed the script to select the best-matching BPASS models. H.T. collected a considerable part of the underlying atomic data to the atmosphere models, contributed to the PoWR atmosphere code, and to the atmosphere analysis and discussion. J.S.V. contributed to the discussion on the evolutionary status and the hydrodynamically consistent atmosphere models.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Astronomy thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

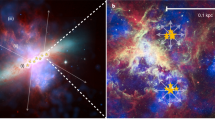

Extended Data Fig. 1 Spectral visualization of potential WN+WO binaries or chance alignments.

Upper panel (a): Comparison of the normalized optical spectrum of M33WR 206 with those of the WN2-star WR 2 and the WO-star WR 142. To check whether the unique appearance of M33WR 206 could also be the product of a WN and WO star, we show two weighted combinations of the latter two stars with the WN2-star providing either 80 % (dash-dotted line) or 95 % (dotted line) of the flux to the optical spectrum. In either case, unobserved features appear with the most prominent ones being highlighted in the figure. Lower panel (b): Similar comparison, but now using the WN4 star WR 6 as the WN component, illustrating that for cooler WN subtypes even more additional features would appear.

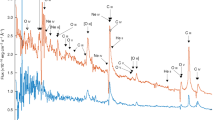

Extended Data Fig. 2 Visualization of the quantitative spectral analysis results of M33WR 206.

Observed spectral and photometric data (blue) for M33WR 206 over-plotted with the best-fitting atmosphere model (red). The uppermost panel shows the spectral energy distribution while the lower panels compare the normalized observed and model spectrum the UV and optical regime. The presence (or absence) of major spectral lines is indicated by black vertical dashes annotated with the corresponding ion.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Visualization of the quantitative spectral analysis results of M31WR 99-1.

Observed spectral and photometric data (blue and green) for M31WR 99-1 over-plotted with the best-fitting atmosphere model (red). The uppermost panel shows the spectral energy distribution while the lower panels compare the normalized observed and model spectrum the UV and optical regime. For the UV (secondmost upper panel), no observation is available. The third panel contains also a zoom-in around the N V 4933/44 line compared to models with different nitrogen abundance (indicated by different colors and line styles). The presence (or absence) of major spectral lines is indicated by black vertical dashes annotated with the corresponding ion.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Visualization of the quantitative spectral analysis results of BAT99 5.

Observed spectral and photometric data (blue and green) for BAT99 5 over-plotted with the best-fitting atmosphere model (red). The uppermost panel shows the spectral energy distribution while the lower panels compare the normalized observed and model spectrum the UV and optical regime. The UV panel (secondmost upper panel) contains an inlet showing a zoom-in around the C IV 1550 wind line compared to models with different carbon abundance (indicated by different colors and line styles). The presence (or absence) of major spectral lines is indicated by black vertical dashes annotated with the corresponding ion.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Comparison in the Hertzsprung Russell Diagram (HRD) with single-star evolution models.

The positions of the discovered WN/WO stars (yellow) and the three other WN2 stars (blue) are compared to GENEC models with an LMC-like metallicity (left panel, Eggenberger et al. 2021 as well as earlier tracks from Meynet et al. (1994) with enhanced mass loss often employed in Starburst99 population synthesis models (right panel). Error bars for the observed WR stars are derived from acceptable spectral reproduction within a sample of at least 100 star-specific models.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Comparison with BPASS evolution models.

HRDs with the best-matching BPASS v2.2.1 (Eldridge et al. 2017, Stanway & Eldridge 2018 single (grey) and binary (light purple) tracks for each of the analyzed WN/WO (yellow) and WN2 stars (blue). For binary solution, the secondary track is indicated by a dashed path. The combined luminosity of primary and secondary is indicated by a semi-transparent filled circle. Error bars for the observed WR stars are derived from acceptable spectral reproduction within a sample of at least 100 star-specific models.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Advanced evolution of the custom GENEC models calculated with our adapted wind mass-loss scheme.

Effective temperature (without wind correction, upper panel), mass (middle panel) and mass-loss rate (lower panel) as a function of age, focusing on the time beyond central hydrogen burning. Similar to the HRD plot in Fig. 4, the surface composition is indicated by the track color and dots mark steps of 50 kyr. For comparison, the derived the effective temperatures, masses, and mass-loss rates of the three WN2 stars and M33WR 206 are indicated as dashed light blue horizontal lines.

Extended Data Fig. 8 HRD with custom MESA models demonstrating the impact of enhanced mixing about the He burning core.

The derived positions of our sample stars compared to tracks from custom MESA calculations without (left) and with (right) overshooting during the core-He burning. The models also use an increased mass loss in the cool star regime to remove a substantial part of the envelope which otherwise employ the standard ‘Dutch’ prescription. The surface composition is indicated by the track color and dots mark steps of 30 kyr.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–7.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Sander, A.A.C., Lefever, R.R., Josiek, J. et al. Discovery of a transitional type of evolved massive star with a hard ionizing flux. Nat Astron (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-025-02719-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-025-02719-z

This article is cited by

-

Unusual objects illuminate new evolutionary paths

Nature Astronomy (2026)