Abstract

Solar flares release a tremendous amount of magnetic energy that subsequently manifests in several forms; the bulk of this energy is transported through the Sun’s atmosphere and explosively heats the chromosphere. While hard X-ray observations have pointed to flare-accelerated electrons as a primary means by which energy is transported following flares, alternative processes undoubtedly act alongside, or even instead of, those energetic electrons. To shed light on this we analysed flare-optimized, high-cadence Solar Orbiter observations. Footpoints from two flare ribbons were observed by the Spectral Imaging of the Coronal Environment (SPICE) instrument. Curiously, those footpoints exhibited contrasting behaviour: one had short-lived yet strong decreases in the Lyman β/Lyman γ line intensity ratio, whereas the other exhibited a more prolonged, moderate dip in that ratio. These observations were compared to synthetic spectra from radiation hydrodynamic simulations of flares driven by various energy transport mechanisms. This revealed that one footpoint was driven by energetic particle precipitation, while the other was driven by enhanced thermal heat flux. The implication is that energetic particles do not dominate along the entirety of flare ribbons. Critically, we must now focus on understanding where, when and why different mechanisms dominate in solar flare energy transport.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Solar flare energy flows from the corona into the lower atmosphere, producing large-scale ribbon-like structures at the bases of loops1. Those ribbons represent the lower atmospheric imprint of coronal energy release. Observations at high spatial and temporal resolution are essential to capture the rapid dynamics and fine-scale structure of these flare ribbons, and provide a window on the energy release and transport processes. The extreme-UV (EUV) portion of the spectrum is valuable, providing access to multiple spectral features formed over a broad temperature range (T ≈ 0.01–>10 MK). However, most EUV spectroscopic observations of flares have been limited in cadence, or lacked critical spatial information, making it challenging to probe the impulsive phase of energy deposition and transport. Here spatially resolved high-cadence (δt = 5.1 s, where t is time) flare footpoint observations taken by the Spectral Imaging of the Coronal Environment instrument (SPICE)2 onboard Solar Orbiter3 are presented. By performing a detailed model–data comparison of the ratio of Lyman β (Lyβ) to Lyman γ (Lyγ) line intensities in flares, we ascertain that this metric can diagnose different mechanisms of flare energy transport, providing clear evidence that particle beams do not dominate in every ribbon location.

High-spatial-resolution observations have revealed substantial substructure within flare ribbons on scales <1″. Distinct brighter kernels appear along the ribbons4,5, and white-light kernel-like patches appear within ribbon structures4,6,7. Spectral properties also show variations along the ribbons, such as Doppler shifts, line broadening and wing asymmetries8,9,10,11. The diversity of spectral behaviour in the flaring solar atmosphere implies that the properties of energy transport from the corona into the lower atmosphere vary notably on small scales.

The canonical picture is that flare energy is transported primarily via accelerated (non-thermal) electrons, revealed by copious evidence of the hard X-rays (HXRs) that they produce12. However, HXRs (and thus non-thermal electrons (NTE)) are often confined to bright, compact footpoints, rather than extended ribbon structures (with some exceptions4,13). These HXR footpoints undergo apparent motion, do not extend over the entirety of optical/UV ribbons and are often associated with the brightest optical/UV sources1,14,15,16.

Explanations14,17,18 for the apparent discrepancy between the spatial extent of HXR sources and flare ribbons include instrumental effects (for example, dynamic range and low spatial resolution) and differences in the nature of UV/optical and HXRs. While those factors certainly play a role, our investigation supports an additional explanation. Namely, that in locations lacking HXR emission, alternative energy transport mechanisms carry flare energy to the lower atmosphere.

Although NTEs are thought to be the primary energy transport mechanism, additional agents must also be considered19, including: non-thermal proton or multi-species beams20,21,22,23, enhanced thermal heat flux from directly heated flare coronae (referred to as thermal conduction (TC) models)24,25,26 or flare-induced Alfvénic waves27,28,29,30. It is not known to what extent these play important roles, or whether they even dominate the energetics in certain flare locations.

High-cadence observations of the Lyman lines present an opportune means to begin to address this. They are strong lines that form in the lower transition region/upper chromosphere, making them very sensitive to flare energy deposition. The characteristics of these optically thick lines depend on the way that their wavelength-dependent opacity and source functions vary with height. Temperature and density can both impact the source function, particularly via the level populations responsible for each line. For instance, higher temperatures can enhance collisional excitation to or from the various the energy levels. Dynamic events that impact the stratification of the atmosphere would therefore be expected to vary the source function of the lines, both in an absolute manner and relative to each other. This would in turn impact the Lyman line profiles and, for our particular interest, the integrated intensity ratios. Studying multiple lines of the same species and charge state is useful as they form close together in altitude, and the relative population of each level will depend on flare-induced plasma conditions. A rare previous observation revealed sharp decreases in the ratio of Lyα/Lyβ line intensities in a flare31 (Supplementary Section 1). That study concluded that some process in the flare populated n = 3 at the expense of n = 2. It is reasonable to expect that the manner in which the atmosphere responds to flares with different energies is reflected by the relative behaviour of those spectra. We demonstrate that this is true using SPICE observations of Lyβ and Lyγ lines.

Results

Overview of the flare

On 23 March 2024 at ~23:40 ut, during Solar Orbiter’s 2024 Major Flare Campaign32, SPICE’s slit crossed flaring footpoints. At this time the spacecraft–Sun distance was ~0.381 au and Solar Orbiter was 11° ahead of the Earth. Supporting 17.4 nm images from the Extreme Ultraviolet Imager’s High Resolution Imager (EUI/HRIEUV)33, and X-ray observations from the Spectrometer/Telescope for Imaging X-rays (STIX)34 were also available. All times quoted are at Solar Orbiter (308.9 s light-travel time earlier than Earth-based assets).

This was a complex region, containing multiple brightenings over a sustained period. An overview of this event is shown in Fig. 1 (the evolution determined from EUI/HRIEUV data is shown in Supplementary Videos 1 and 2). An M2.5 class flare occurred first, near y ≈ −180″. Approximately 11 min later, a compact two-ribbon microflare appeared ~100″ farther south (1″ ≈ 275 km at that spacecraft–Sun distance) and is the focus of our study. SPICE’s slit crossed through both ribbons of the microflare. More imagery of the flare is included in Supplementary Section 2 for context, with multi-temperature Solar Dynamics Observatory images shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. It seems that SPICE observed two non-conjugate footpoints during the microflare, one in the upper ribbon and one in the lower ribbon. The footpoint of the upper ribbon was much brighter, with a very transient impulsive enhancement (~30 s), followed by a longer secondary decay over the course of several minutes. The footpoint in the lower ribbon was notably fainter, and exhibited more gradual changes in behaviour. The morphology of the flare sources caught by the SPICE slit can be seen in spacetime maps of the region shown in Extended Data Fig. 1 and is discussed further in Supplementary Sections 3 and 4. Light curves of each flare footpoint show that, to within the 5.1 s cadence, the emissions peaks largely coincide temporally (Extended Data Fig. 2 and Supplementary Section 3). Although the SPICE light curves and spacetime maps exhibited periodicities on the order of 1 min, these were determined to be due to spacecraft pointing while tracking the active region (Supplementary Section 5 and Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3), and did not impact the line ratios.

The top left panel shows an EUI/HRIEUV snapshot, indicating the location of the M2.5 flare and the microflare ribbons that SPICE observed. Intensities are in data numbers per second per pixel (DN s−1 px−1). The cyan lines indicate the approximate location of the SPICE 4″ slit. The top right panels show a sequence of EUI/HRIEUV images that illustrate the development of the microflare that SPICE observed a portion of. The bottom panel shows the evolution of the EUV and X-ray emission. The background image is the Fe xx 72.156 nm spectral line intensity observed by the SPICE slit as a function of time (note the reversed colour scale). Bright loops from the M2.5 flare are present in the north. The microflare emission is seen in the south (starting at around t ≈ 800 s). The time evolution of the EUI/HRIEUV 174 Å emission is overlaid, along with X-ray observations taken by the Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellite’s X-ray Sensor (GOES/XRS; blue line) and STIX (4–9 keV in green, and 25–50 keV in red). The microflare is much fainter than the GOES M2.5 flare seen earlier. The GOES and STIX signal are consequently dominated by emissions from the M2.5 flare. Nevertheless, STIX observes a small enhancement above E > 20 keV at the time of the microflare. The EUI/HRIEUV 174 Å intensity for the M2.5 flare and the microflare are shown separately (violet and orange lines, respectively). Both profiles show the classic flare picture with rapid time variations (a few seconds) during the impulsive phase originating from the flare ribbons, followed with a delay of several minutes of the emissions from the cooled-down flare loops. Note that we have corrected the SPICE pointing information for an approximate x, y = [−18, −50]″ offset between EUI/HRIEUV and SPICE.

X-ray observations were dominated by the decaying signal from the M2.5 flare. However, the microflare produced a measurable increase in the STIX signal by approximately one-third at high energies (above 20 keV). Owing to the weak signal, STIX imaging could not reliably determine the position of this newly brightened component. Nevertheless, the co-temporal intensity enhancement from the microflare as observed by EUI/HRIEUV (Fig. 1) supports the association of this increase with the microflare. From a spectral analysis (Methods) we obtained an electron power-law index of δ = 3.5 ± 0.9 and a non-thermal power of P = 2.2 × 1025 erg s−1 for an assumed low-energy cutoff of Ec = 20 keV. Accounting for uncertainty in both the area into which electrons are injected (Methods), A, and Ec, we consider three sets of STIX-guided parameters for flare modelling (F = P/A is the energy flux density of the distribution): A, δ = 3.5, Ec = 20 keV, F = 4.4 × 109 erg s−1 cm−2; B, δ = 3.5, Ec = 15 keV, F = 1.6 × 1010 erg s−1 cm−2; and C, δ = 3.5, Ec = 10 keV, F = 4.4 × 1010 erg s−1 cm−2.

Observed Lyman line ratio

The Lyβ and Lyγ lines exhibited strong intensity increases within the flare sources. Extended Data Fig. 3 shows examples of the spectral response (see also Supplementary Section 4). We focus on the integrated intensity to avoid potential issues with SPICE’s complicated spectral point spread function (PSF)35, obtaining the ratio of Lyβ/Lyγ, Rβγ. In non-flaring sources Rβγ ≈ [2.4−3.4], with some variations in space but little variation in time (see also Supplementary Section 5 and Supplementary Fig. 4). Maps of the spatial and temporal evolution are shown in Fig. 2 (Extended Data Fig. 4 includes intensity contours, highlighting flare sources). Clear decreases in Rβγ in response to flare heating are observed, particularly in the stronger ribbon. Some regions of reduced Rβγ appear outside the flare regions, but these are probably artefacts due to the SPICE spatial PSF.

The top panel shows a spacetime map of Rβγ in which decreases in the ratio in response to the flare on 23 March 2024 were observed. The large spatial PSF results in ‘ghost images’ of the flare that (although weak in intensity) show up in Rβγ maps as that quantifies the relative response. The bottom panels show the lifetime of the decrease in Rβγ in flare sources from the strong ribbon (bottom left) and weaker ribbon (bottom right). The thin coloured lines represent light curves from different pixels within each source, the thick black line is the weighted mean Rβγ and the red dashed line is a Gaussian fit to the mean. The full-width at half-maximum (FWHM) of the mean light curve is indicated in each plot. The green curves are the Lyβ intensities from pixel 415 (solar − Y ≈ −251.49″) in the strong footpoint and pixel 386 (solar-Y ≈ −283.49″) in the weak footpoint, as functions of time relative to the Rβγ minimum. Error bars for Rβγ result from a standard error propagation of the uncertainties in individual intensities of Lyβ and Lyγ (which themselves account for the combined uncertainty54 in intensity from photon shot noise, dark currents and readout noise). Note that a −50″ offset has been applied to SPICE’s solar-Y pointing information.

The magnitudes and lifetimes of Rβγ decrease differ notably between the flare sources. The stronger ribbon source exhibits a large decrease to Rβγ ≈ [1.4–2], which is very transient in nature. This is co-temporal with the impulsive peak in intensity. Following the intensity peak, Rβγ rapidly rises to Rβγ > 2, and then more slowly returns to pre-flare levels (similar to the intensity light curves from that source that exhibit a secondary decay period lasting several minutes). In contrast, the weaker ribbon source had a more modest and gradual decrease, only dropping to a minimum value of Rβγ ≈ [2.0–2.4]. This minimum was longer-lived, followed by a slow return to the pre-flare level. Although the characteristics during the periods of minimum Rβγ differ markedly in each footpoint, in the latter stages of the evolution (presumably post-energy injection) the magnitudes of Rβγ are more comparable while the atmospheres cool. Figure 2 shows the superposed light curves of Rβγ, as well as the weighted mean from each flare source. The contrast of the magnitudes and lifetimes of Rβγ suggests that two distinct scenarios took place: (1) an impulsive and short-lived decrease to Rβγ < 2, with lifetimes tR ≈ 30 s and (2) a gradual and long-lived decrease but with Rβγ > 2, with a lifetime on the order of several dozen seconds.

Modelled Lyman line ratio

To test the hypothesis that differences in the observed Rβγ between the two flare footpoints could be attributed to different energy transport mechanisms dominating in different parts of the ribbon, we performed a series of numerical simulations using the RADYN radiation hydrodynamics code36,37,38,39 (Methods). This one-dimensional field-aligned numerical code models the solar atmosphere’s response to flare energy injection, accounting for the effects of non-local, non-equilibrium radiation transfer. In recent years RADYN has become a workhorse for the flare modelling community40,41.

Eleven flare simulations were produced with differing flare energy transport mechanisms: (1) four driven by NTEs (NTE models); (2) one driven by a non-thermal proton distribution (NTP model); (3) one driven by a multi-species NTE plus proton distribution (NTMS model); (4) and five in which flare energy was deposited directly at the apex of the loop. In the latter scenario, designed to simulate in situ heating of the corona following reconnection, energy is carried to the lower atmosphere via a thermal heat flux. Those models are referred to as the thermal conduction (TC) models. Of these, NTE1, NTE2 and NTE3 were guided by parameter sets derived from STIX observations (A, B and C, respectively). For NTE4 we experimented with an energy flux that was an order of magnitude greater. The parameters for each simulation are summarized in Table 1. For consistency, energy was injected at a constant rate for 20 s in both the particle-beam and TC experiments, apart from TCGradual. The atmospheres evolved differently depending on whether energy was transported via non-thermal particles or thermal conduction, as illustrated in Extended Data Figs. 5 (temperature), 6 (electron density) and 7 (H(n = 4)/H(n = 3) population ratio). The TC simulations resulted in extremely sharp temperature and density gradients, whereas particle-beam-driven flares heated over greater spatial extents (see also Supplementary Section 6).

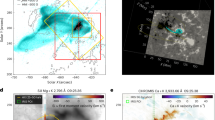

Synthetic SPICE spectra were generated by using RADYN flare atmospheres as inputs to the RH15D radiation transfer code42 and applying instrumental effects. From those, we obtained the synthetic Rβγ. Characteristics of the spectra themselves are discussed in Supplementary Section 8, with some examples shown Supplementary Figs. 7 and 8. Figure 3 shows a summary of the results, with the remainder presented in Extended Data Fig. 8. The pre-flare Rβγ values are higher than the observed pre-flare values, probably stemming from the pre-flare structure of the atmosphere. Once the flare begins, the rapidly evolving temperature, density and ionization structure seems to obviate that initial discrepancy and values are closer to those of the observed flare.

The simulations shown are from NTE3 (top left), TC2 (bottom left) and TCGradual (bottom right). Black lines (grey circles) are the results direct from RADYN+RH15D, and the red lines (red open circles) are the values once processed through SPICE’s instrumental response at 5 s cadence. The blue bands are the minimum values of Rβγ that occurred during the strong, impulsive feature in the observed flare. The top right panel shows a superposed histogram of the Rβγ light curves from the 31 flare models from the FCHROMA simulation grid with Fpeak > 3 × 1010 erg s−1 cm−1, where Fpeak is the peak instantaneous energy flux density injected over the 20 s triangular pulse (this peak was at 10 s). The grey line is the mean. The gold line is the observed ratio from the strong footpoint clipped to the time range of the models, showing close agreement.

Each of the particle-beam-driven flares produced Rβγ = [1.5–2]. This was transient, with Rβγ beginning to increase immediately on cessation of the non-thermal particle bombardment. As with the observations of the strong footpoint, Rβγ remained decreased compared with the pre-flare level. NTE1 showed the required temporal behaviour, but the ratio was not quite as low as the observed ratio for the duration of flare heating. Of the particle-beam-driven flare simulations, NTE3, NTP and NTMS were most consistent with the observations of the strong footpoint.

In the TC simulations, although Rβγ was reduced it was still notably larger than that for the particle-beam-driven flares, with Rβγ ≈ [2.2–3.0]. The temporal behaviour also differed, such that Rβγ remained at a fairly constant level for the duration of the simulation, even after energy injection into the coronal portion of the loop ceased. Thus, the TC simulations were more consistent with the gradual, longer-lived and smaller decrease in Rβγ observed in the weaker footpoint.

To confirm that the overall behaviour implied by our experiments holds true over a broader range of NTE distributions, we used a large grid of RADYN models produced by the FCHROMA project43. All simulations with Fpeak > 3 × 1010 erg s−1 cm−2 (where Fpeak is the peak instantaneous energy flux density injected over a 20 s triangular pulse, with the peak at 10 s) were selected (spanning δ = [3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8] and Ec = [10, 15, 20, 25] keV), providing 31 additional experiments (Methods). Although variations in Rβγ are present in each simulation due to the differing spectral characteristics of the NTEs, Rβγ exhibited general properties consistent with the strong source observed by SPICE. Figure 3 shows a 2D histogram of Rβγ in which the light curves from each of the 31 FCHROMA simulations were superposed on a common epoch with t = 0 s having the minimum value of Rβγ. Light curves of Rβγ in general had more structure than those in our experiments, probably due to the temporal profile of the injected non-thermal energy flux density in the FCRHOMA grid, which was a triangular pulse, as opposed to the constant injection used in this study. Constant energy injection produced sharp gradients in Rβγ, in contrast to the triangular injection. This implies that the observed light curves may encode information about the evolution of the deposited energy, which warrants further detailed study, as does the variation of Rβγ with δ, Ec or F. It is interesting that Rβγ observed in the strong footpoint shows a wider, more Gaussian-like shape than the FCRHOMA simulations, potentially indicating the temporal profile. In a similar vein, in TCGradual energy was injected to the coronal portion of the loop more gradually, with an increasing magnitude for 35 s, then decreasing for 35 s. In that instance the initial decrease in Rβγ (bottom right panel of Fig. 3) was more gradual. It is also possible that the relatively wide SPICE slit captured sources at slightly different stages in their evolution, which, when coupled with spatial PSFs and multidimensional energy transport, smoothed out the temporal response.

Although it might be expected that non-thermal collisions between the non-thermal particle beams and ambient hydrogen led to these differences, this is not the case. Re-running the NTE3 experiment but with those collisions turned off did not change the behaviour of Rβγ. This is because the line cores and near wings in our flare models form in high-temperature, high-density plasma, where thermal collisions dominate. The impact of the non-thermal particles on Rβγ is indirect, felt due to the violent hydrodynamic evolution of the atmosphere. In the flares driven by non-thermal particle beams, the flare effects are present over a larger part of the upper chromosphere than in the TC flares. While the electron density in the line formation height was high in every experiment (ne > 1012−15 cm−3), the temperature in the formation region was much higher in the flares driven by non-thermal particle beams (T > 25 kK, compared with T < 25 kK). Thermal collisions between H(n = 3 to 4) populated the Lyγ upper level at the expense of the Lyβ upper level. This happened to a greater degree and over a larger height range in the particle-beam-driven flare experiments. In addition, the difference in the average plasma temperature from the line core forming regions of Lyβ and Lyγ was smaller in the particle-beam-driven flares than in the TC-driven flares. Differences between the source functions were therefore larger in the TC experiments. Extended Data Figs. 9 and 10 illustrate this.

Following the cessation of particle beams, temperature gradients steepened, reducing the spatial extent of overpopulation of H(n = 4) relative to H(n = 3) and increasing Rβγ while the atmosphere cools via conduction. In this cooling stage, Rβγ is comparable in the NTE and TC experiments. The models also allowed exploration of other H line ratios, discussed in Supplementary Section 9, with Lyα ratios shown in Supplementary Fig. 9.

Flare arcade modelling

To further constrain energy transport during the microflare we constructed a RADYN_Arcade44 model of SPICE O vi 103.76 nm and Fe xx 72.156 nm emission (Methods). A sequence of our NTE and TC RADYN loop models was grafted onto a 3D magnetic skeleton, with new loops activated every 2 s and emission summed along the line of sight (making this only applicable to optically thin conditions). The position of the loops was intended to be representative of the region, but not exactly reproduce it. The specific intention was to illustrate that the SPICE slit observed non-thermal-particle-heated footpoints from the upper ribbon (producing the stronger source) and TC-heated footpoints from the lower ribbon (producing the weaker source).

Figure 4 shows snapshots of the arcade progression where a bundle of NTE3 loops were placed alongside TC1 loops. An O vi spacetime map bearing a close resemblance to the observations (Extended Data Fig. 1) was extracted from a 4″ slit. The weaker source originating from the TC footpoints crosses the slit first, with a stronger, transient source in the north heated by NTEs appearing a short time later.

The top row shows the evolution of the O vi model flare arcade normalized to the maximum intensity for the time points indicated. The row below shows the corresponding evolution for Fe XX. The cyan lines represent the region used to extract a synthetic SPICE slit. The bottom left panel shows a map of the Fe xx emission summed through time, with the arcade skeleton overlaid. The blue loops are RADYN TC1 simulations and the gold loops are the RADYN NTE3 simulations. The bottom right panel shows synthetic spacetime maps of the O vi 103.76 nm (top) and Fe xx 72.156 nm (bottom) lines processed through the SPICE response including the PSF. A much brighter, transient source in the upper part of the slit originates from the NTE-heated footpoints, and the weaker source in the lower portion of the slit was from the TC-heated footpoint. Later, hot loops form between the ribbons, as seen in the observations.

A spacetime map of Fe xx emission is also consistent with the observations, with a brief enhancement in the NTE3 footpoint before loops form in a diffuse region between the ribbons. Similar spacetime maps generated using the weaker NTE1 or NTE2 simulations failed to produce a brighter O vi footpoint in the north or sufficient Fe xx emission. While NTE3 is favoured to explain the Fe xx emission, a hybrid model in which additional flare heating was injected directly in the corona to the NTE2 model did result in a hotter loop with greater Fe xx emission (Supplementary Section 6). That model retained the required Rβγ properties of the NTE-only experiments.

However, the wavelength-integrated emission produced by the NTE3 model was too intense by ~11× for O vi 103.76 nm and ~2× for Fe xx, potentially indicating that the NTE energy flux lies between that of NTE2 and NTE3. Other causes could also be (for example) the footpoint area filling factor, the temporal profile of injection or an overly dense pre-flare transition region or corona.

Discussion

Our results indicate spatial variability in the dominant energy transport mechanisms across flare ribbons. This challenges the picture of energy transport primarily driven by NTEs along the full extent of flare ribbons. Striking similarities in the properties of the Lyman line ratios exist between SPICE observations and solar flare models. The Lyβ/Lyγ ratios have revealed that the bright portion in the northern ribbon caught by SPICE’s slit was heated by precipitating non-thermal particles, while a portion of the southern ribbon was instead produced via an enhanced thermal heat flux from a directly heated corona. RADYN_Arcade modelling illustrates how this would appear in a SPICE spacetime map. While we posit here that non-conjugate clusters of loops either produced energetic particles or did not, it is possible that the particle precipitation was instead highly asymmetric, only reaching one footpoint. Indeed, observations of hard microflares (microflares with a particularly small δ ≈ 3–4, indicating efficient particle acceleration) often exhibit only one non-thermal footpoint45. Nevertheless, this would still result in one footpoint experiencing the precipitation of non-thermal particles, and the other only a thermal heat flux.

The properties of Rβγ are also linked to the temporal evolution of the precipitating non-thermal particles. An open question in flare physics is what the typical dwell time of precipitating particles in a particular location is. It was demonstrated recently that the lifetime of ribbon fronts is directly related to the duration of the weak precipitation of NTE46. In a similar fashion, here we find that the temporal profile of Rβγ is related to the injection duration as well as the evolution of F(t). We infer from the SPICE observations of Rβγ that NTEs precipitated into that portion of the ribbon for t = 20–30 s. This is consistent with other inferred dwell times47, and with quasiperiodic HXR bursts with characteristic timescales of 4–128 s (refs. 48,49). From a detailed study of an X-class flare, periods of 7–35 s were identified, with imaging data suggesting that individual bursts represented separate injections48,49. It is important to note that in that flare the spectral index exhibited soft–hard–soft evolution within individual bursts, indicating the local evolution of δ in time. Future combinations of STIX and SPICE Lyman line observations will continue to shed light on how F(t), δ(t) and Ec(t) evolve within individual flare sources.

We have illustrated a specific way in which Lyman lines are diagnostically useful in determining where and when non-thermal-particle precipitation dominates energy transport, as well how the properties of the energetic particle distribution change through time. This is particularly important, as these Lyman line diagnostics can probe much smaller spatial scales than those afforded by the typical resolution of HXR observations. This warrants additional investigation to determine precisely how to extract this essential information. Future observations with the upcoming Solar-C/High-Throughput Spectroscopic Telescope (Solar-C/EUVST)50 will be able to rapidly scan flare ribbons while observing Lyα, Lyβ and Lyγ, offering great potential.

Teasing apart which energy transport mechanisms dominate spatially and temporally over the whole structure of a flare will be aided by forthcoming observations from the Daniel K. Inouye Solar Telescope (DKIST) and the Multi-slit Solar Explorer (MUSE)51. They will provide spectral coverage of the whole ribbon structure at high temporal cadence. A key next step should be to identify diagnostics based on the spectra that those observatories will provide, and to focus on understanding when, where and why each energy transport mechanism dominates.

Methods

Details of the observations

For the Major Flare Campaign, SPICE observed in sit-and-stare mode using the 4″ slit, capturing several wavelength windows in both the short-wavelength (SW; 70.4–79.0 nm) and long-wavelength (LW; 97.3–104.9 nm) channels, with spectral lines that sample a large temperature range from the chromosphere to very hot flare plasma (those lines are listed in Supplementary Table 1). Science-ready Level-2 (L2) data, obtained from the Solar Orbiter Archive (SOAR; https://soar.esac.esa.int/soar/) were used in this study, with the calibration pipeline described in the instrument paper2. Specifically, data from Data Release 5 were used52, which include several important updates to the calibration pipeline. The L2 SPICE data have a wavelength plate scale of 0.009623 nm per pixel for the LW channel and 0.0097517 nm per pixel for the SW channel. Onboard spectral summing was used to reduce telemetry, allowing sustained high-cadence observations over several hours to attempt to catch a flare, with an exposure time of texp = 4.8 s and overall cadence δt = 5.1 s. The spatial plate scale along the slit was 1.09798″, giving an approximate slit pixel size of 1,105 km × 303 km. Post-launch, the FWHM of the spatial PSF has been estimated to be 6.3 pixels, or 6.7″ (refs. 52,53), which for this dataset equates to ~2,032 km along the slit. For the SW channel the spectral resolution has been estimated as 7.8 pixels, and for the LW channel it is 9.4 pixels. The PSF is also tilted in the slit plane, such that there can be a y − λ rotation on the detector. Strong intensity gradients can thus introduce Doppler signal artefacts35. Uncertainties in the intensity within each wavelength bin were obtained using the sospice software package (https://pypi.org/project/sospice/), which calculates the contribution from photon shot noise, dark currents and readout noise54.

This EUI/HRIEUV dataset is the L2 data from SOAR without any additional data reduction. Images have a pixel scale of 0.5″, with a resolution of 1″. Long- (2 s) and short- (0.04 s) exposure images were interleaved, with the latter giving a sequence of six images with cadence of 2 s followed by a single long-exposure image32. We used the long-exposure images, with a 16 s cadence, to provide context for the SPICE spectra.

Only a coarse alignment of SPICE and EUI/HRIEUV was performed, as EUI/HRIEUV was only used to provide context for the structures that SPICE observed. This was done by shifting the helioprojective longitude of the SPICE slit from the SPICE L2 metadata, creating an EUI/HRIEUV spacetime map at that location and then comparing the relative distance between features that the slit crossed and strong brightenings between SPICE and EUI/HRIEUV spacetime maps. A shift in helioprojective longitude (solar-X) of −18″ was necessary, along with a roughly −50″ offset in helioprojective latitude. This is adjusted for when SPICE coordinates are presented. From the sequence of EUI/HRIEUV maps, it seems that the edge of a newly brightening flare source crossed the SPICE slit first. Around 30–45 s later the bright central portion of a flare ribbon crossed the slit ~30″ farther north, extending along the slit. Later, flare loops appeared, joining footpoints along the ribbons; portions of these were also visible in SPICE spacetime maps.

STIX is the X-ray instrument onboard Solar Orbiter, and provides X-ray diagnostics in a 4–150 keV energy range with a spectral resolution of 1 keV and an angular resolution down to 7″. Through the bremsstrahlung mechanism, STIX provides diagnostics of the hottest flare plasmas and electrons accelerated during the flare. Owing to the relatively low data rate, STIX essentially operates at all times without the need to restrict observations to dedicated campaigns.

STIX HXR analysis

We applied standard STIX spectral fitting for a thick target model using the STIX Ground Software Version v0.5.2. An albedo component was added using the flare location as seen from Solar Orbiter. At the onset of the microflare, the thermal emission from the M2.5 flare is still at about 75% of its peak flux value in the STIX thermal channels, precluding a meaningful analysis of the microflare’s thermal X-rays. Thus we could not add a thermal function to the fit and no cutoff energy could be constrained. Instead we assumed a fixed low-energy cutoff Ec = 20 keV in the initial fit. The M2.5 flare provides the largest part of the background signal during the time interval of the microflare. We subtracted a linearly decreasing background derived from the time range before and after the non-thermal peak of the microflare. As the signal was weak and the subtracted background is even slightly more intense than the flux increase due to the microflare, the observed spectrum is noisy and the fit parameters are only approximations. Nevertheless, these observations give a guideline for the electron beam injected into the flare ribbons for the purposes of modelling reasonable values.

To derive the energy deposition rate (energy flux density), F (in erg s−1 cm−2) by flare-accelerated electrons into the flare ribbons, the area of the flare ribbons needed to be determined (F = P/A). This is generally a difficult observation, as flare ribbons are narrow and typically unresolved4, and often the sources are saturated in (E)UV images (such as those from the Solar Dynamics Observatory/Atmospheric Imaging Assembly (AIA)). EUI/HRIEUV provides unsaturated images (or images that are close to unsaturated, but with no blooming). However, even with the high-angular-resolution EUI/HRIEUV images taken at 0.381 au, the flare ribbons are not resolved in the perpendicular direction (the ribbon width). In the following, we assume a width of 1″ (~275 km, representing two EUI/HRIEUV pixels) as an upper limit, which is the resolution of EUI/HRIEUV. The northern ribbon of the microflare is much more prominent than the southern ribbon, suggesting that the southern ribbon underwent less heating. From the 50% contour level, the length of the northern ribbon was estimated to be 4.5″ and the length of the southern ribbon to be 2″. This gives a total approximate area of A ≈ 5 × 1015 cm2. Given that EUI/HRIEUV does not resolve the flare sources fully, the flare ribbons could easily be as narrow as 0.5″, reducing the area by a factor of 2.

With non-thermal power P = 2.2 × 1025 erg s−1, we then have F = 4.4 × 109 erg s−1 cm−2. This is a relatively low F value, but the microflare is also a relatively small flare that is dwarfed by the decay phase of the M2.5 flare. Still, F = 4.4 × 109 erg s−1 cm−2 can be treated as a lower limit. We performed the spectral fitting with fixed Ec = 20 keV due to the difficulty of separating the thermal component from the decaying M2.5 flare. Therefore, Ec = 20 keV is an upper limit, and consequently the energy deposition rate is a lower limit. The rate increases for a smaller Ec by a factor of (Ec/20)−δ+1; for example, for Ec = 15 keV, the rate increases by about a factor of ~2, and for Ec = 10 keV the rate increases by a factor of ~5.7. Reducing the flare area estimate could also increase the rate by up to a factor of 2. In summary, F = 4.4 × 109 erg s−1 cm−2 is a lower limit on the energy deposition rate, but a value of up to ~10× higher is plausible as well. Values around or well above 1011 erg s−1 cm−2 are unlikely.

Measuring R βγ

Similar to ref. 55, owing to the non-Gaussian line shapes, we measured the wavelength-integrated line intensity by integrating over fixed wavelength ranges that capture the bulk of the line intensity while avoiding contributions from nearby lines. A range of λ0 ± 0.15 nm was used for both lines. Obtaining a reliable measure of the continuum was difficult due to the wavelength range of each window, so the continuum was not subtracted. However, the continuum contributes only a relatively small amount to the overall line intensity55, and is also included in the modelling. From the radiance of each line we calculated Rβγ with standard error propagation using the uncertainty on the SPICE intensities.

Lifetimes of the Rβγ decrease were estimated by shifting the light curves of each pixel within the flare sources to a common epoch, with t = 0 s being the minimum value of Rβγ. Gaussian functions were then fitted to each pixel, as well as to the weighted mean of Rβγ within each flare source. The lifetime was taken to be the FWHM of this mean light curve’s Gaussian fit, and the FWHM from each pixel was used to calculate the standard deviation of lifetimes.

Flare radiation hydrodynamic modelling

As in ref. 56, we used the version of RADYN that employs the FP code57 to model the transport and thermalization of non-thermal particles (including return currents), and we included the electric pressure broadening profiles from refs. 58,59 for the hydrogen Balmer lines. Beginning around T ≈ 5 kK, the relative cross-sectional area in our experiments increases through the chromosphere and transition region, varying by a factor of 3 between the chromosphere and the lower corona (T ≈ 1 MK). This was derived from the normalized inverse of an imposed magnetic field stratification that itself was defined by a hyperbolic tangent function following60. Given that RADYN does not model the full Lyman line profiles, for the purposes of mimicking partial frequency redistribution when modelling radiative losses, we used snapshots of RADYN atmospheres as input to the RH15D radiation transfer code42. The same RH15D set-up as ref. 46 was used, where hydrogen and calcium populations from RADYN were not recalculated by RH15D and were instead kept fixed while computing the level populations of other species. Using the non-equilibrium H level populations and electron density (ne) from RADYN mitigates the fact that RH15D solves the statistical equilibrium problem. This also allows the inclusion of non-thermal collisional excitation and ionization of H(n = 1). In each experiment, the pre-flare atmosphere was a loop with an 11 Mm half-length, apex temperature of T = 3.15 MK and ne = 7.6 × 109 cm−3 (see ref. 39).

The temporal profile over which energy is injected to individual footpoints during flares is not known, so for simplicity we used a constant energy injection for all simulations except the TCGradual experiment and the FCHROMA simulations.

The NTP model used the mid-range value of the energy flux density derived from STIX, and assumed the same spectral index as the NTE1–3 experiments, with an ad hoc Ec = 50 keV. This was guided by recent models of flare particle acceleration that found that protons could be accelerated down to tens of kiloelectronvolts22. The electron distribution in the NTMS experiment was the same as that in NTE2. The proton component used the same spectral index δ = 3.5 but a lower energy flux density.

When simulating the TC experiments, we injected a volumetric energy flux over the top 4 Mm of the loops such that the integrated energy flux densities are the values quoted in Table 1. These values were chosen to be comparable to typical NTE experiments. To aid convergence, the volumetric heating rate in TC4 was spread over a wider range of heights (the top 6 Mm of the loop). For the TCGradual experiment, the energy was added more gradually to the coronal portion of the loop over a period of 70 s. To be clear, thermal conduction was included in every simulation, but the other models did not include the additional thermal heat flux resulting from the directly heated corona.

Synthetic SPICE spectra

Spectra from RADYN+RH15D were converted to be synthetic SPICE observations by (1) recasting to SPICE spectral plate scales, (2) multiplying by the SPICE pre-launch effective area, (3) converting to total photon numbers, accounting for the solid angle of a SPICE spatial pixel and spectral dispersion, (4) summing over an exposure time of 5 s, (5) applying Poisson noise, (6) performing spectral binning and (7) converting back to physical units of SPICE L2 data.

The PSF was also accounted for in our synthetic spectra. As SPICE has a non-trivial PSF that is tilted on the detector, combining spectral and spatial information from nearby pixels, synthetic detector images had to be constructed. For each simulation we constructed a series of synthetic SPICE detector images (y − λ), one per 5 s exposure, that represented 832 pixels along the slit dimension. Each slit position within an exposure was populated by non-flaring Lyβ and Lyγ line profiles from our model, including Poisson noise so that this background was not uniform (no other noise sources were added). Then, for pixels roughly at the locations of the ribbons in the microflare, we added the synthetic flare profiles corresponding to that particular exposure (pixels at y = [354–370] and y = [408– 422]). Each synthetic flare source was uniform (that is, no spatial variation). Using the PSF parameters listed in the first column from table 1 of ref. 35, which modelled the SPICE PSF by comparing IRIS and SPICE observations of the same region, we applied a model PSF to our synthetic SPICE exposures using the SHARPPEST package35. For the remainder of our analysis, we selected pixel y = 415 to investigate modelled spectra and Rβγ. See Supplementary Section 7 (in particular Supplementary Fig. 6) for an illustration of this process, as well as a demonstration of the artificial Doppler shifts that were introduced at the edges of the flare sources by the tilted PSF.

Synthetic Lyman ratios from FCHROMA models

From the grid of FCHROMA models (https://star.pst.qub.ac.uk/wiki/public/solarmodels/start.html) we selected all those with a peak energy flux Fpeak > 3 × 1010 erg s−1 cm−2 (fluence Ftot > 3 × 1011 erg cm−2), which left 31 simulations covering δ = [3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8], Ec = [10, 15, 20, 25] keV, Fpeak = [3 × 1010, 1 × 1011] erg s−1 cm−2. Not every combination of parameters was available, with the higher energy cases restricted to δ = [3, 4, 5].

We did not process these through RH15D to obtain the more detailed Lyman line profiles, but instead integrated the Lyα, Lyβ and Lyγ profiles directly from the RADYN simulations, which is sufficient for this sanity check of our overall conclusion. We note that these simulations were produced the public version of RADYN39,43, although this will not alter the conclusions. The use of the FCHROMA grid of models also allows us to ensure that the pre-flare stratification does not adversely impact the trends (an initial pre-flare atmosphere similar to the VALC model from ref. 61, as opposed to the hotter pre-flare atmosphere used in our bespoke simulations). Another difference between that grid of models and those presented earlier is that the NTE distributions were injected with a time-varying energy flux density, in a triangular temporal profile with peak flux at t = 10 s and total heating duration of 20 s.

Constructing the RADYN_Arcade model of SPICE emission

In the RADYN_Arcade framework44 we can model optically thin emission along the line of sight, taking into account the superposition of different sources, their geometry and the location on the solar disk. RADYN flare loops are grafted onto a magnetic skeleton that is defined in 3D space, which in this instance was guided loosely by the Solar Orbiter observations, with a Sun–Earth distance of 0.381 au and arcade in the same region of the solar disk.

The first set of ten loops mimicked the bundle of loops that seemed to span the southern flare ribbon to a western brightening. Starting with one footpoint at [−441, −289]″ and its conjugate footpoint at [−398, −265]″ (which assumes a semi-circular loop with radius set by considering the RADYN loop length), each subsequent loop was shifted westwards to create the ribbon segment. The remaining 38 loops spanned the southern ribbon to the brightenings farther north, spreading eastwards. The first 12 loops were the TC1 simulation, the next 12 were the NTE3 simulation and the remaining 24 were the TC1 simulation.

Loops were considered symmetric, so the same RADYN half-loop simulation was grafted onto each leg to create a full loop. The first ten loops had an inclination of 10°, and the remaining had an inclination − 20°. All had footpoint areas of 6 × 1014 cm2 at the base of the transition region, which equates to a diameter of 1″, the upper limit inferred from EUI/HRIEUV. A total of 48 loops were created, with a new loop activating every 2 s. This loop activation time was an ad hoc choice, but guided by the expectation that new loops activate rapidly. Newly brightened flare sources cause ribbons to exhibit an apparent elongation, and often subsequent expansion, as magnetic reconnection proceeds, producing flare arcades. Apparent elongation speeds have typically been observed to range from 10–200 km s−1 (refs. 18,62,63,64), and recent observations of so-called slipping reconnection have observed some sources with even greater speeds of up to thousands of kilometres per second in larger flares65. Our RADYN_Arcade model has an apparent speed of ~60 km s−1, on the lower end of the observed range.

Along each loop the O vi 103.76 nm and Fe xx 72.156 nm emission was synthesized in each grid cell using atomic data from CHIANTI66 under the assumption of ionization equilibrium, together with temperatures, densities and velocities from RADYN (Doppler shifts were applied considering the line of sight to each loop voxel). CHIANTI v11 (ref. 67) was used, including density-dependent processes with the exception of charge exchange. An oxygen abundance of 8.69 was used68, defined on the standard logarithmic scale with a reference hydrogen abundance of 12.

Spectra from each loop pixel were projected onto a 2D observational grid, which had [1, 1.09798]″ pixels (the plate scale in solar-Y was equivalent to the SPICE observations). Multiple loops could project emission into each pixel, which was summed, accounting for the superposition of optically thin emission along the line of sight. Maps were made at 0.5 s cadence. From these maps, a portion equivalent to the 4″ SPICE slit was extracted, taking the mean of emission between x = − 440″ to −436″, placed to include NTE3 footpoints in the northern ribbon and TC1 footpoints in the southern ribbon. This synthetic slit emission was then passed through the SPICE instrumental response, and had a model y − λ PSF applied. From those synthetic sit-and-stare SPICE spectra, spacetime maps were created by integrating the O vi and Fe xx lines over wavelength.

By virtue of the 1D-to-3D approach we could include the coupled response of the detailed chromosphere with the coronal portion of the loop, incorporating the superposition of loops and viewing angle effects on the radiation. However, we did not account for multidimensional effects that would be at play in the actual arcade, including 3D radiative heating, turbulence in termination shocks at the looptops and compressive actions of neighbouring loops. An interesting future endeavour would be to try to couple this with codes that are capable of modelling those effects69 with the detailed chromosphere of RADYN.

Data availability

Data from SPICE, EUI and STIX are publicly available from the Solar Orbiter Archive at https://soar.esac.esa.int/soar/. The Solar Orbiter Observing Plan ID is L_BOTH_HRES_HCAD_Major-Flare - LB5. Observations from SDO/AIA are available from the Stanford Joint Science Operations Support Center at http://jsoc.stanford.edu/. Flare simulations produced for this manuscript are available via Zenodo for RADYN at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17582687 (ref. 70) and RH15D at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17574576 (ref. 71). FCHROMA model output is available from the project’s website at https://star.pst.qub.ac.uk/wiki/public/solarmodels/start.html.

Code availability

The simulation codes are available via the following links: https://folk.universitetetioslo.no/matsc/radyn (public version of RADYN), https://github.com/solarFP/FP (FP), and https://github.com/ITA-Solar/rh (RH15D). The SHARPPEST python package was used to apply the model SPICE PSF and is available here https://github.com/jeplowman/SHARPESST. For reading and preparing SPICE data we used Python packages available via GitHub: sunraster to read SPICE data into NDCube72,73 format (https://github.com/sunpy/sunraster) and sospice to caclulate SPICE intensity uncertainties (https://github.com/solo-spice/sospice). STIX Ground Software, written in IDL, is also available via GitHub (https://github.com/i4Ds/STIX-GSW/releases). This research also used the following open-source software packages: fiasco74 and SunPy v5.0 (refs. 75,76).

References

Fletcher, L. et al. An Observational overview of solar flares. Space Sci. Rev. 159, 19–106 (2011).

SPICE Consortiumet al. The Solar Orbiter SPICE instrument. An extreme UV imaging spectrometer. Astron. Astrophys. 642, A14 (2020).

Müller, D. et al. The Solar Orbiter mission. Science overview. Astron. Astrophys. 642, A1 (2020).

Krucker, S. et al. High-resolution Imaging of solar flare ribbons and its implication on the thick-target beam model. Astrophys. J. 739, 96 (2011).

Thoen Faber, J. et al. High-resolution observational analysis of flare ribbon fine structures. Astron. Astrophys. 693, A8 (2025).

Kerr, G. S. & Fletcher, L. Physical properties of white-light sources in the 2011 February 15 solar flare. Astrophys. J. 783, 98 (2014).

Kowalski, A. F., Allred, J. C., Daw, A., Cauzzi, G. & Carlsson, M. The atmospheric response to high nonthermal electron beam fluxes in solar flares. I. Modeling the brightest NUV footpoints in the X1 solar flare of 2014 March 29. Astrophys. J. 836, 12 (2017).

De Pontieu, B. et al. A new view of the solar interface region from the Interface Region Imaging Spectrograph (IRIS). Sol. Phys. 296, 84 (2021).

Xu, Y. et al. Extreme red-wing enhancements of UV lines during the 2022 March 30 X1.3 solar flare. Astrophys. J. 958, 67 (2023).

Wang, L. F., Li, Y., Li, Q., Cheng, X. & Ding, M. D. Spectral features of the solar transition region and chromospheric lines at flare ribbons observed with IRIS. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 268, 62 (2023).

Pietrow, A. G. M., Druett, M. K. & Singh, V. Spectral variations within solar flare ribbons. Astron. Astrophys. 685, A137 (2024).

Holman, G. D. et al. Implications of X-ray observations for electron acceleration and propagation in solar flares. Space Sci. Rev. 159, 107–166 (2011).

Masuda, S., Kosugi, T. & Hudson, H. S. A hard X-ray two-ribbon flare observed with Yohkoh/HXT. Sol. Phys. 204, 55–67 (2001).

Asai, A. et al. Difference between spatial distributions of the Hα kernels and hard X-ray sources in a solar flare. Astrophys. J. Lett. 578, L91–L94 (2002).

Fletcher, L. & Hudson, H. S. Spectral and spatial variations of flare hard X-ray footpoints. Sol. Phys. 210, 307–321 (2002).

Krucker, S., Fivian, M. D. & Lin, R. P. Hard X-ray footpoint motions in solar flares: comparing magnetic reconnection models with observations. Adv. Space Res. 35, 1707–1711 (2005).

Liu, C., Lee, J., Gary, D. E. & Wang, H. The ribbon-like hard X-ray emission in a sigmoidal solar active region. Astrophys. J. Lett. 658, L127–L130 (2007).

Cheng, J. X., Kerr, G. & Qiu, J. Hard X-ray and ultraviolet observations of the 2005 January 15 two-ribbon flare. Astrophys. J. 744, 48 (2012).

Kerr, G. S. et al. Requirements for progress in understanding solar flare energy transport: the impulsive phase. Bull. Am. Astron. Soc. 55 (2023).

Tamres, D. H., Canfield, R. C. & McClymont, A. N. Beam-induced pressure gradients in the early phase of proton-heated solar flares. Astrophys. J. 309, 409 (1986).

Kerr, G. S. et al. Prospects of detecting nonthermal protons in solar flares via Lyman line spectroscopy: revisiting the Orrall-Zirker effect. Astrophys. J. 945, 118 (2023).

Yin, Z., Drake, J. F. & Swisdak, M. Simultaneous proton and electron energization during macroscale magnetic reconnection. Astrophys. J. 974, 74 (2024).

Battaglia, A. F. & Krucker, S. New insights into the proton precipitation sites in solar flares. Astron. Astrophys. 694, A58 (2025).

Zarro, D. M. & Lemen, J. R. Conduction-driven chromospheric evaporation in a solar flare. Astrophys. J. 329, 456 (1988).

Brosius, J. W. Extreme-ultraviolet spectroscopic observation of direct coronal heating during a C-class solar flare. Astrophys. J. 754, 54 (2012).

Ashfield, W. H. & Longcope, D. W. Relating the properties of chromospheric condensation to flare energy transported by thermal conduction. Astrophys. J. 912, 25 (2021).

Fletcher, L. & Hudson, H. S. Impulsive phase flare energy transport by large-scale Alfvén waves and the electron acceleration problem. Astrophys. J. 675, 1645–1655 (2008).

Reep, J. W., Russell, A. J. B., Tarr, L. A. & Leake, J. E. A hydrodynamic model of Alfvénic wave heating in a coronal loop and its chromospheric footpoints. Astrophys. J. 853, 101 (2018).

Kerr, G. S., Fletcher, L., Russell, A. J. B. & Allred, J. C. Simulations of the Mg II k and Ca II 8542 lines from an Alfvén wave-heated flare chromosphere. Astrophys. J. 827, 101 (2016).

Russell, A. J. B. in Alfvén Waves Across Heliophysics: Progress, Challenges, and Opportunities (ed. Keiling, A.) 39–73 (Wiley, 2024).

Lemaire, P., Choucq-Bruston, M. & Vial, J. C. Simultaneous H and K Ca II, h and k Mg II, Lα and Lβ H I profiles of the April 15, 1978 solar flare observed with the OSO-8/L.P.S.P. experiment. Sol. Phys. 90, 63–82 (1984).

Ryan, D. F. et al. Solar Orbiter’s 2024 major flare campaigns: an overview. Sol. Phys. 300, 152 (2025).

Rochus, P. et al. The Solar Orbiter EUI instrument: the Extreme Ultraviolet Imager. Astron. Astrophys. 642, A8 (2020).

Krucker, S. et al. The Spectrometer/Telescope for Imaging X-rays (STIX). Astron. Astrophys. 642, A15 (2020).

Plowman, J. E. et al. SPICE point spread function correction: general framework and capability demonstration. Astron. Astrophys. 678, A52 (2023).

Carlsson, M. & Stein, R. F. Does a nonmagnetic solar chromosphere exist? Astrophys. J. Lett. 440, L29–L32 (1995).

Abbett, W. P. & Hawley, S. L. Dynamic models of optical emission in impulsive solar flares. Astrophys. J. 521, 906–919 (1999).

Allred, J. C., Hawley, S. L., Abbett, W. P. & Carlsson, M. Radiative hydrodynamic models of the optical and ultraviolet emission from solar flares. Astrophys. J. 630, 573–586 (2005).

Allred, J. C., Kowalski, A. F. & Carlsson, M. A unified computational model for solar and stellar flares. Astrophys. J. 809, 104 (2015).

Kerr, G. S. Interrogating solar flare loop models with IRIS observations 1: overview of the models, and mass flows. Front. Astron. Space Sci. 9, 1060856 (2022).

Kerr, G. S. Interrogating solar flare loop models with IRIS observations 2: plasma properties, energy transport, and future directions. Front. Astron. Space Sci. 9, 1060862 (2023).

Pereira, T. M. D. & Uitenbroek, H. RH 1.5D: a massively parallel code for multi-level radiative transfer with partial frequency redistribution and Zeeman polarisation. Astron. Astrophys. 574, A3 (2015).

Carlsson, M. et al. The F-CHROMA grid of 1D RADYN flare models. Astron. Astrophys. 673, A150 (2023).

Kerr, G. S., Allred, J. C. & Polito, V. Solar flare arcade modeling: bridging the gap from 1D to 3D simulations of optically thin radiation. Astrophys. J. 900, 18 (2020).

Battaglia, A. F. et al. The observational evidence that all microflares that accelerate electrons to high energies are rooted in sunspots. Astron. Astrophys. 691, A172 (2024).

Kerr, G. S., Polito, V., Xu, Y. & Allred, J. C. Solar flare ribbon fronts. II. Evolution of heating rates in individual flare footpoints. Astrophys. J. 970, 21 (2024).

Graham, D. R. et al. Spectral signatures of chromospheric condensation in a major solar flare. Astrophys. J. 895, 6 (2020).

Collier, H., Hayes, L. A., Battaglia, A. F., Harra, L. K. & Krucker, S. Characterising fast-time variations in the hard X-ray time profiles of solar flares using Solar Orbiter’s STIX. Astron. Astrophys. 671, A79 (2023).

Collier, H. et al. Localising pulsations in the hard X-ray and microwave emission of an X-class flare. Astron. Astrophys. 684, A215 (2024).

Shimizu, T. et al. The Solar-C_EUVST mission. Proc. SPIE 11118, 1111807 (2019).

De Pontieu, B. et al. The multi-slit approach to coronal spectroscopy with the Multi-slit Solar Explorer (MUSE). Astrophys. J. 888, 3 (2020).

SPICE Consortium et al. Data release 5.0. https://spice.osups.universite-paris-saclay.fr/spice-data/release-5.0/release-notes.html (2024).

Fludra, A. et al. First observations from the SPICE EUV spectrometer on Solar Orbiter. Astron. Astrophys. 656, A38 (2021).

Huang, Z. et al. Imaging and spectroscopic observations of extreme-ultraviolet brightenings using EUI and SPICE on board Solar Orbiter. Astron. Astrophys. 673, A82 (2023).

Warren, H. P., Mariska, J. T. & Wilhelm, K. High-resolution observations of the solar hydrogen Lyman lines in the quiet Sun with the SUMER instrument on SOHO. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 119, 105–120 (1998).

Kerr, G. S., Kowalski, A. F., Allred, J. C., Daw, A. N. & Kane, M. R. An optically thin view of the flaring chromosphere: non-thermal widths in a chromospheric condensation during an X-class solar flare. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 527, 2523–2548 (2024).

Allred, J. C., Alaoui, M., Kowalski, A. F. & Kerr, G. S. Modeling the transport of nonthermal particles in flares using Fokker-Planck kinetic theory. Astrophys. J. 902, 16 (2020).

Tremblay, P. E. & Bergeron, P. Spectroscopic analysis of DA white dwarfs: Stark broadening of hydrogen lines including nonideal effects. Astrophys. J. 696, 1755–1770 (2009).

Kowalski, A. F. et al. The atmospheric response to high nonthermal electron-beam fluxes in solar flares. II. Hydrogen-broadening predictions for solar flare observations with the Daniel K. Inouye solar telescope. Astrophys. J. 928, 190 (2022).

Kowalski, A. F. Bridging high-density electron beam coronal transport and deep chromospheric heating in stellar flares. Astrophys. J. Lett. 943, L23 (2023).

Vernazza, J. E., Avrett, E. H. & Loeser, R. Structure of the solar chromosphere. III. Models of the EUV brightness components of the quiet sun. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 45, 635–725 (1981).

Fletcher, L., Pollock, J. A. & Potts, H. E. Tracking of TRACE ultraviolet flare footpoints. Sol. Phys. 222, 279–298 (2004).

Qiu, J. Observational analysis of magnetic reconnection sequence. Astrophys. J. 692, 1110–1124 (2009).

Joshi, N. C. et al. Generalization of the magnetic field configuration of typical and atypical confined flares. Astrophys. J. 871, 165 (2019).

Lörinčík, J., Aulanier, G., Dudík, J., Zemanová, A. & Dzifčáková, E. Velocities of flare kernels and the mapping norm of field line connectivity. Astrophys. J. 881, 68 (2019).

Dere, K. P., Landi, E., Mason, H. E., Monsignori Fossi, B. C. & Young, P. R. CHIANTI - an atomic database for emission lines. Astron. Astrophys. Suppl. Ser. 125, 149–173 (1997).

Dufresne, R. P. et al. CHIANTI—an atomic database for emission lines—paper. XVIII. Version 11, advanced ionization equilibrium models: density and charge transfer effects. Astrophys. J. 974, 71 (2024).

Asplund, M., Amarsi, A. M. & Grevesse, N. The chemical make-up of the Sun: a 2020 vision. Astron. Astrophys. 653, A141 (2021).

Druett, M., Ruan, W. & Keppens, R. Exploring self-consistent 2.5D flare simulations with MPI-AMRVAC. Astron. Astrophys. 684, A171 (2024).

Kerr, G. S. et al. RADYN model output for a study on variation of energy transport in solar flares by Kerr et al. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17582687 (2025).

Kerr, G. S. et al. RH15D model output for a study on variation of energy transport in solar flares by Kerr et al. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17574576 (2025).

Ryan, D. F. et al. ndcube: manipulating n-dimensional astronomical data in Python. J. Open Source Softw. 8, 5296 (2023).

Ryan, D. F. et al. A unified framework for manipulating N-dimensional astronomical data and coordinate transformations in Python: the NDCube 2 and Astropy APE-14 world coordinate system APIs. Astrophys. J. 956, 44 (2023).

Barnes, W. et al. wtbarnes/fiasco: v0.2.3. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10612118 (2024).

The SunPy Communityet al. The SunPy project: open source development and status of the version 1.0 core package. Astrophys. J. 890, 68 (2020).

Mumford, S. J. et al. SunPy. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8037332 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the following funding: NASA’s Early Career Investigator Program (grant number 80NSSC21K0460; G.S.K. and A.F.K.), NASA’s Heliophysics Supporting Research programme (grant number 80NSSC21K0010; G.S.K. and R.O.M.), NASA’s Heliophysics Theory, Modelling and Simulations programme (J.C.A. and G.S.K.), NASA’s SOGI programme (grant number 80NSSC24K1242; S.K.), GSFC SO/SPICE project funding (T.A.K., P.R.Y., A.R.I., J.W.B., J.M.R.-G. and G.S.K.), the PHaSER co-operative agreement (grant number 80NSSC21M0180; A.R.I., J.W.B., J.M.R.-G. and G.S.K.), a Royal Society–Research Ireland University Research Fellowship (grant number URF/R1/241775; L.A.H.), the European Office of Aerospace Research and Development (grant number FA8655-22-1-7044P00001; R.O.M.), the Science and Technology Facilities Council (grant number ST/X000923/1; R.O.M.) and SwRI’s Solar Orbiter subcontract from GSFC (grant number 80GSFC20C0053; J.E.P.). Solar Orbiter is a space mission of international collaboration between ESA and NASA, operated by ESA. The STIX instrument is an international collaboration between Switzerland, Poland, France, Czech Republic, Germany, Austria, Ireland and Italy. The EUI instrument was built by CSL, IAS, MPS, MSSL/UCL, PMOD/WRC, ROB and LCF/IO with funding from the Belgian Federal Science Policy Office (BELSPO/PRODEX PEA 4000112292 and 4000134088); the Centre National d’Etudes Spatiales (CNES); the UK Space Agency (UKSA); the Bundesministerium für Wirtschaft und Energie (BMWi) through the Deutsches Zentrum für Luftund Raumfahrt (DLR); and the Swiss Space Office (SSO). The development of SPICE has been funded by ESA member states and ESA. It was built and is operated by a multinational consortium of research institutes supported by their respective funding agencies: STFC RAL (UKSA, hardware lead), IAS (CNES, operations lead), GSFC (NASA), MPS (DLR), PMOD/WRC (Swiss Space Office), SwRI (NASA) and UiO (Norwegian Space Agency).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Research and manuscript writing were led by G.S.K. He designed the study, analysed SPICE data (with input from A.R.I., J.M.R.-G., J.E.P., P.R.Y., T.A.K. and J.W.B.) and performed the model–data comparisons. S.K. analysed the STIX data. G.S.K. and J.C.A. performed and interpreted RADYN and RADYN_Arcade modelling, with input from A.F.K. J.M.R.-G. analysed periodicities in the SPICE data and spacecraft pointing. J.E.P. assisted with application of the SPICE model PSF. D.F.R., A.R.I., L.A.H., T.A.K. and G.S.K. were involved in designing various elements of the Major Flare Solar Orbiter Observing Plan. G.S.K., S.K., J.C.A., J.M.R.-G., A.R.I., D.F.R., L.A.H., R.O.M., A.F.K., J.E.P., P.R.Y., T.A.K. and J.W.B. contributed to discussing and interpreting the results, and writing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Astronomy thanks Ayumi Asai, Malcolm Druett and Jaroslav Dudik for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Spacetime maps of several spectral lines during the 23rd March 2024 microflare sources observed by SPICE.

H I Lyβ (T ≈ 10 kK; top left), S III 101.249 nm (T ≈ 50 kK; top right), O VI 103.761 nm (T ≈ 280 kK; middle left), C III 97.702 nm (T ≈ 70 kK; middle right), Ne VIII 77.043 nm (T ≈ 630 kK; bottom left), and Fe XX 72.156 nm (T ≈ 10 MK; bottom right). Spectra were integrated in wavelength over the range quoted on each panel, with continuum subtracted only for Ne VIII and Fe XX. Saturation is present in the C III image. The strong, transient flare ribbon appears at Solar-Y ≈ -252”, the weaker ribbon appears at Solar-Y ≈ -285”, and the hot loops from the main M flare are present around Solar-Y ≈ [-190,-170]”. The colour tables have been saturated to highlight both the strong and weak ribbon sources. Note that a -50” offset has been applied to SPICE’s solar-Y pointing information.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Lightcurves from various species during the 23rd March 2024 microflare, ordered by roughly increasing formation temperature H I to Fe XX).

Each curve is normalised to its own maximum. The top panel is a pixel within the stronger flare footpoint (a -50” offset has been applied to SPICE’s solar-Y pointing information), and the bottom panel shows the weaker flare footpoint. Note that C III is saturated at the peak of the strong flare footpoint.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Spectra from a single pixel located within the strong flare footpoint in the 23rd March 2024 microflare.

The top row is Lyβ, and the bottom shows Lyγ and Fe XVIII. In all panels, the grey curve is a profile from the pre-flare (23:42:24 UT). Intensity doubles within one 5.1 s snapshot, and peaks around 15 s later. The vertical lines show the wavelength range used for the integration when calculating Rβγ. Note that the intensity scale changes from panel to panel. Error bars on intensity represent combined uncertainties [35] on the SPICE data due to photon shot noise, dark currents, and readout noise. A -50” offset has been applied to SPICE’s solar-Y pointing information quoted on each panel.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Spacetime map of the Lyman line ratio Rβγ, including contours of Fe XX and H I Lyγ.

The contours illustrate that notable decreases correspond to the strongest flare kernels. Other, smaller decreases from the typical background values are also sometimes associated with flare locations, and some are artifacts (ghost images), likely caused by the large instrumental PSF. Note that a -50” offset has been applied to SPICE’s solar-Y pointing information.

Extended Data Fig. 5 The evolution of temperature at three snapshots of each flare simulation.

Colour represents each simulation, and the grey-shaded regions are the pre-flare stratification. Panels in the top row are the NTE experiments, the middle row shows experiments involving non-thermal protons, and the bottom row panels are the TC experiments.

Extended Data Fig. 6 The evolution of electron density at three snapshots of each flare simulation.

Colour represents each simulation, and the grey-shaded regions are the pre-flare stratification. Panels in the top row are the NTE experiments, the middle row shows experiments involving non-thermal protons, and the bottom row panels are the TC experiments.

Extended Data Fig. 7 The evolution of the ratio of populations of H(n=4)/H(n=3) at three snapshots of each flare simulation.

Colour represents each simulation, and the grey-shaded regions are the pre-flare stratification. Panels in the top row are the NTE experiments, the middle row shows experiments involving non-thermal protons, and the bottom row panels are the TC experiments.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Synthetic Rβγ from the flare simulations that were not shown in the Main Text.

The top row is the NTE experiments, the middle row is the experiments involving protons, and the bottom row is the TC experiments. Black lines (grey circles) are the results direct from RADYN+RH15D, and the red lines (red open circles) are the values once processed through SPICE’s instrumental response. The blue bands are the values of Rβγ during the strong, impulsive feature in the observed flare.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Plasma properties in the Lyβ and Lyγ line core formation region in the NTE3 simulation.

The line intensity ratio is in the top left, the formation height is bottom left, the temperature is top middle, the bulk velocity is bottom middle, the electron density is top right, and the level population ratios are bottom right. The black solid lines are Lyβ, and red dashed lines are Lyγ.

Extended Data Fig. 10 Plasma properties in the Lyβ and Lyγ line core formation region in the TC2 simulation.

The line intensity ratio is in the top left, the formation height is bottom left, the temperature is top middle, the bulk velocity is bottom middle, the electron density is top right, and the level population ratios are bottom right. The black solid lines are Lyβ and red dashed lines are Lyγ.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–9, Table 1 and Discussion.

Supplementary Video 1

The evolution of the flaring region from 23:25:46 ut on 23 March 2024 to 00:10:02 ut on 24 March 2024, as observed by Solar Orbiter EUI/HRIEUV 174. Times are at Solar Orbiter, which was located at 0.381 au.

Supplementary Video 2

The evolution of the microflare from 23:25:46 ut on 23 March 2024 to 00:10:02 ut on 24 March 2024, as observed by Solar Orbiter EUI/HRIEUV 174. Times are at Solar Orbiter, which was located at 0.381 au.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kerr, G.S., Krucker, S., Allred, J.C. et al. Spatial variation of energy transport mechanisms within solar flare ribbons. Nat Astron (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-025-02747-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-025-02747-9