Abstract

Organic transformations mediated by the transient formation of iminium ions have shown remarkable synthetic potential for the construction of enantioenriched molecules. The possibility to access their first singlet excited state (S1) under light irradiation has led to the development of previously inaccessible transformations. However, the triplet state (T1) reactivity remains limited and typically requires external photosensitizers. Here we show that structurally modified chiral iminium ions, integrated into extended π-systems, directly engage in T1 reactivity. This modified conjugated architecture was designed to overcome the intrinsic photophysical limitations of conventional iminium ion chemistry, enabling access to previously inaccessible excited-state reaction manifolds. The resulting system allows organocatalytic enantioselective [2 + 2] photocycloadditions without the need for external sensitizers. Mechanistic studies, involving spectroscopic techniques and computational methods, elucidate the role of the T1 intermediate as the key reactive intermediate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

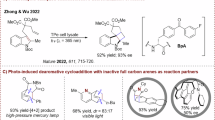

The rationalization and understanding of reaction mechanisms in asymmetric organocatalysis have enabled its development and broad application in organic synthesis1,2. In the field of covalent organocatalysis, the traditional use of iminium-ion intermediates has established a powerful catalytic platform for the stereocontrolled construction of new chemical bonds, facilitating the nucleophilic conjugate addition at the β-carbon of unsaturated carbonyl compounds3. This activation mode led to the development of a plethora of catalytic asymmetric methods and to the synthesis of structurally diversified products. On the other hand, the pioneering studies of Mariano on the photochemistry of iminium ions revealed that the light-excited state reactivity of these species is sharply different from the one in the ground state. In fact, upon light excitation, iminium ions can behave as photo-oxidants, triggering the formation of radical species from suitable radical precursors or taking part in stereospecific photocycloadditions4,5,6,7. Recently, the combination of visible light with asymmetric organocatalysis allowed the discovery of previously uncharted chemical reactivities. These findings contributed to dissipate the general perception that highly energetic excited states are not suitable intermediates for stereoselective transformations8. In 2017, Melchiorre and co-workers showed that the excited state of catalytic chiral iminium ions can be efficiently used for the generation of radical species, which can be subsequently trapped in a stereoselective manner8,9,10,11 (I; Fig. 1a). More recently, Alemán and co-workers developed an organocatalytic asymmetric [2 + 2] photocycloaddition in which the singlet excited state of iminium ions, transiently generated from acyclic conjugated ketones, is intercepted by various dienes to obtain optically active cyclobutane derivatives12 (II; Fig. 1a). These advances have enabled access to previously untapped chemical space with well-defined three-dimensional architectures, which is central to the field of asymmetric synthesis. While the singlet excited state (S1) reactivity of iminium ion has proved its generality for a variety of diverse transformations, the use of the triplet excited state (T1) is far less developed. In a seminal work, Bach and co-workers reported that the T1 state of iminium ions can be accessed by means of energy transfer catalysis, thanks to their lower triplet energy compared with the corresponding carbonyl compounds. The selection of an appropriate photosensitizer allowed the development of an asymmetric [2 + 2] photocycloaddition of the chiral iminium ions and various alkenes via energy transfer catalysis13,14 (III; Fig. 1a).

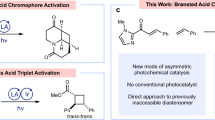

Leveraging the T1 reactivity of chiral iminium ions under direct excitation remains an unmet goal for the synthetic chemical community. In fact, the direct excitation of transiently generated chiral iminium ions to reach their T1 state via intersystem crossing (ISC) would provide an attractive synthetic strategy for the development of innovative asymmetric photocycloadditions15,16,17,18,19,20 to obtain enantioenriched cyclic derivatives21 without the use of an external photocatalyst. However, this approach is hampered by the intrinsic photophysical properties of iminium ions. While conjugated carbonyl compounds can efficiently undergo ISC from their S1 state to the corresponding T1 state (1n–π* to 3π–π*) engaging in [2 + 2] photocycloadditions, the photochemistry of the analogous iminium ions is governed by their singlet reactivity, as the ISC involves the forbidden transition 1π–π* to 3π–π* (refs. 6,7,13,14,22).

Despite these conceptual rules on the reactivity of classical conjugated iminium ions, we questioned whether altering the chemical nature of the conjugated system, such as its incorporation into heteroaromatics, could be the key strategy to access their elusive T1 reactivity. For example, the indole moiety has been already used to develop [2 + 2] dearomative photocycloadditions23,24,25,26, mostly via energy transfer catalysis27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34. We thus identified indole-3-carboxaldehyde as a promising candidate for our investigations. Embedding the conjugated iminium ion within a π-extended aromatic framework could mitigate the inherent photophysical limitations that typically hinder their T1 reactivity. This approach, in turn, could enable catalytic enantioselective [2 + 2] dearomative photocycloadditions—a reaction class that remains markedly underexplored35,36. In fact, while the cyclobutane core is present in a variety of bioactive drugs and natural products, including paesslerin A37, rumphellaone A38 or the Food and Drug Administration-approved drug apaludamide39, its enantioselective construction still represents an open challenge for the scientific community.

Herein, we describe the successful realization of an organocatalytic asymmetric [2 + 2] photocycloaddition involving the key reactivity of the T1 state of photoactive iminium ions (Fig. 1b). This methodology relies on the formation of intermediate IV and its ability to access, upon light absorption and ISC, a reactive T1 state V that undergoes a stereoselective dearomative [2 + 2] photocycloaddition, providing a wide variety of enantioenriched polycyclic products VI. We demonstrated that specific primary-amine organocatalysts, classically used under polar reactivity, can efficiently catalyse stereoselective transformations involving highly energetic excited intermediates. Photophysical studies and transient spectroscopy revealed the nature of the reactive excited state. Time-dependent density functional theory (TD-DFT) and density functional theory (DFT) study calculations were conducted to shed light on the formation and nature of this fleeting intermediate.

Results

Optimization studies

At the outset of our studies, we decided to test the enantioselective intramolecular [2 + 2] photocycloaddition of 1-(pent-4-enoyl)-1H-indole-3-carbaldehyde (1) in the presence of trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and the Jørgensen–Hayashi organocatalyst 2a (20 mol%) under light irradiation using a Kessil lamp (427 nm). No product formation was observed after 24 h (Table 1, entry 1). We assumed that the high degree of steric hindrance of the organocatalyst, combined with the poor electrophilic character of aldehyde 1, renders the condensation process inefficient. On the other hand, the use of primary amine-based organocatalysts immediately delivered more satisfactory results (Table 1, entries 2–4). Chiral diamine 2d provided the desired product 3 in 62% yield and 91% enantiomeric excess (e.e.). A solvent screening identified CHCl3 as the optimal for this transformation (Supplementary Table 2). Carrying out the reaction in the presence of an excess of acid additive improved the reaction yield up to 97% while shortening the reaction time from 24 h to 6 h (Table 1, entry 5; Supplementary Table 3). Finally, we performed a series of control experiments to verify the photochemical and radical nature of the transformation (Table 1, entries 6–8). The reaction does not occur in the absence of light nor of the organocatalyst, and the product formation is partially suppressed when performing the reaction under air.

Mechanistic investigations

We next turned our attention to the investigation of the reaction mechanism. Initially, we verified the capability of iminium ion 4 to absorb visible light. Indeed, upon mixing an equimolar amount of aldehyde 1 and organocatalyst 2d in the presence of TFA, a new absorption band appears in the visible region of the spectrum, thus suggesting the formation of the photoactive intermediate 4 (ref. 10; Fig. 2a). We then investigated one of the most intriguing aspects of this transformation, namely, the nature of the excited state of the iminium ion 4 that is involved in the enantioselective [2 + 2] cycloaddition. To this end, we prepared iminium ion 5 that lacks the terminal olefin functional group. While this species cannot react in the photocycloaddition process, it was used as a model compound to compare its photophysical behaviour with the reactive intermediate 4. We first performed steady-state luminescence measurements upon excitation at 360 nm to follow the fate of the singlet excited state in 4 and 5. Both compounds display an intense emission centred at 445 nm, which can be assigned to fluorescence from the S1 state of the iminium ion. Importantly, the fluorescence quantum yield (Φ) is comparable for both 4 and 5, as is the fluorescence lifetime measured by time-correlated single-photon counting (TCSPC; Fig. 2a; for further details, see Supplementary Figs. 4–7 and the related discussion). These results strongly suggest that the S1 state cannot be responsible for the observed reactivity. We then performed laser flash photolysis (LFP) studies on both 4 and 5 to monitor their T1 state. For both compounds, a similar transient absorption spectrum is detected upon laser excitation at 355 nm, which is characterized by ground state bleaching below 400 nm, a sharp absorption centred at 410 nm and a broad absorption in the red portion of the visible spectrum (Fig. 2b,c). Accordingly, the transient species can be mainly assigned to the T1 state of the iminium ion. In the case of the unreactive iminium 5, the transient absorption signal at 700 nm decays towards the baseline within a hundred microseconds (Fig. 2d). The decay kinetics of compound 5 is sensitive to the presence of dioxygen, and a lifetime of τ = 12 μs can be estimated under N2-purged conditions. Both of these observations support that the transient species detected by LFP is the triplet excited state of the iminium ion. More importantly, in the case of the iminium 4, the transient signal at 700 nm decays more rapidly (Fig. 2d), indicating quenching of the triplet state in the presence of the olefin functional group. Thus, this experimental evidence strongly corroborates the participation of the T1 state in the [2 + 2] reaction leading to the formation of the desired cycloadduct.

a, Steady-state luminescence studies. UV–vis absorption spectroscopy to verify the formation of iminium ion 4 by formation of a new band in the visible region. Comparison of the fluorescence quantum yields ΦF and fluorescence lifetimes τ(S1) of compounds 4 and 5. λ is the wavelength of electromagnetic radiation. b, Transient absorption spectra of 4. c, Transient absorption spectra of 5. d, Kinetic decay measured at 700 nm of the triplet excited state of 4 compared with 5. OD, optical density. e, Control experiment using a triplet quencher. r.t., room temperature. f, Stereochemical outcome of the organocatalytic enantioselective [2 + 2] photocycloaddition starting from the two diastereoisomers 7-(E) and 7-(Z). Depending on the stereochemical outcome (stereodivergent versus stereoconvergent process), the involvement of a singlet or triplet excited state can be suggested. The epimerization of the additional stereogenic centre is ruled out by the unchanged d.r. value during the reaction course.

To further prove the triplet reactivity in the present reaction, a control experiment under the optimized reaction conditions was performed in the presence of 1 equivalent of the triplet quencher 2,5-dimethylhexa-2,4-diene. As shown in Fig. 2e, no product formation was observed, with almost quantitative recovery of the starting material 1. On the other hand, carrying out the reaction in the presence of an iridium-based triplet sensitizer greatly accelerated the reaction rate, albeit in lower enanantioselectivity due to the poor discrimination between the activation of substrate 1 and intermediate 4 (for additional results and discussion, see Supplementary Scheme 1).

Finally, substrates 7-(E) and 7-(Z) were employed as structural probes to further confirm our mechanistic proposal6 (Fig. 2f). Indeed, [2 + 2] photocycloadditions that occur at the S1 state are typically stereospecific processes due to the concerted character of their mechanism, and for this reason, the geometry of the double bond is retained into the corresponding product. On the other hand, stereoconvergent [2 + 2] photocycloadditions are indicative of a step-wise mechanism, which typically involves T1 reactivity. For this reason, a series of experiments using either 7-(E) or 7-(Z) were performed under the optimized reaction conditions. While substrate 7-(E) furnished the corresponding cycloadduct in 6.5:1 diastereoisomeric ratio (d.r.) and 50% yield after 2 h, a lower d.r. (1.5:1 in the same major diastereoisomer) was obtained when employing 7-(Z). The formation of both diastereoisomers, regardless of the double bond geometry, suggests that the present photocycloaddition occurs through a step-wise mechanism that involves the T1 state of the iminium ion intermediate. Furthermore, the diastereoisomeric ratio is constant even at lower conversion values, ruling out a scenario in which one isomer of the product interconverts into the other during the reaction course6.

Computational investigations

To support the proposed reaction manifold and gain information on the nature of the involved intermediates and transitions, we carried out a series of DFT and TD-DFT studies40 (Fig. 3). All calculations are provided electronically in the ioChem-BD repository41.The calculations show that photoexcitation of 4 (S0) leads to the relaxed S1 state intermediate 4 (S1) in which the iminium moiety is no longer planar owing to a distortion out of the plane of the indole core towards the Re face of its reactive C=C (+75.2°, for further details see ‘Computational studies’ section of Supplementary Information and Supplementary Fig. 16). The relaxed 4 (S1) intermediate is not productive for the observed reactivity (see the discussion related to Supplementary Fig. 17), confirming that the reaction must proceed through a triplet state. Monitoring the potential energy surfaces of the other excited states of iminium ion 4 (S1) as the iminium distorts towards the Re face of the indole C = C, we observed that the S1 surface comes to within 1.66 kcal mol−1 of the T1 surface but never crosses it (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 18).

a, Relative electronic energy profile for the unconstrained TD-DFT minimization (relaxation) of 4 (S1) after photoexcitation of 4 (S0), viewed with out-of-plane iminium distortion towards the Re face of the C=C indole bond involved in the [2 + 2] cycloaddition. The reaction coordinate is the CCCN dihedral marked in green in 4 (0° when fully planar): surfaces for S0, T1 and T2 are also shown for comparison; all other low-lying excited states are omitted for clarity. b, Representations of the S1 and the T2 states at MECP1 (S1–T2) as electron–hole pairs (difference between squared natural transition orbitals (NTOs); orange areas denote maximum localization of the excited electron). c, The relative free energy profile (∆G) of the proposed reaction pathway for the organocatalytic enantioselective [2 + 2] photocycloaddition. Only the pathway leading to the observed enantiomer is presented.

Interestingly, it was possible to locate a minimum energy crossing point (MECP1) between the S1 and the T2 excited states (for example, at +37.4° in the case under examination in Fig. 3b). We concluded from these findings that the observed triplet reactivity should prevalently transit through the T2 state, with direct S1 → T1 ISC remaining unlikely. While a fraction of the photoexcited 4 (S1) could directly cross to T2 through MECP1, since the S1–T2 transition is spin-prohibited, it is likely that the majority of photoexcited molecules reach the relaxed photoexcited intermediate 4 (S1) before climbing back up to the MECP1 (Fig. 3b). Here, a precise quantification of spin–orbit coupling effects governing the S1–T2 transition is not performed as it requires higher level calculations.

Subsequent relaxation from MECP1 on the T2 surface shows that, as the iminium moiety is further on its way back to planarity from +37.4°, the T1 state is readily encountered at a second MECP2. This new T1 state further relaxes to a first order transition state TS1 that preludes the formation of the first C–C bond. The resulting intermediate (Int-A) can then cross from the T1 state to the open shell singlet (Int-B) with a virtually barrierless transition. Finally, the transition state TS2 leads to radical–radical recombination of Int-B, providing the final cycloadduct 9. A complete mechanistic description of the reaction, including investigation of possible sources of enantioselectivity, is provided in the ‘Computational studies’ section of Supplementary Information, along with orbital representations of salient stationary points along the favoured pathway.

Scope of the reaction

While 4CzIPN (2,4,5,6-tetrakis(9H-carbazol-9-yl) isophthalonitrile) was used for the preparation of racemic samples, the generality of the reaction was evaluated using the optimized reaction conditions. A wide variety of functional groups could be substituted at the indole core without substantially affecting the reaction yield or stereoselectivity (Table 2; products 10–25, 44–84% yield and 72–92% e.e.).

X-ray analysis on a single crystal of product 14 was used to infer both the absolute and relative configuration of the [2 + 2] cycloadduct, and the configuration of all the other products was assigned by analogy. It was also possible to introduce variations at the tethered olefin, furnishing products 26 and 27 with comparable values of yield and enantioselectivity (40% and 80% yield and 84% and 94% e.e., respectively).

Finally, the cyclobutane derivative 28 featuring four contiguous stereogenic centres was obtained in 84% yield, 75% e.e. and 9:1 d.r. We next focussed our efforts on expanding the generality of our approach to an intermolecular version of the reaction. Remarkably, indole 29 reacted smoothly with a series of different alkenes delivering the desired enantioenriched cyclobutanes with satisfactory levels of yield under the very same reaction conditions (Fig. 4a). For example, products 30 and 30′ were isolated using 1-hexene as a reaction partner, providing 51% combined yield, 2.5:1 d.r. and good levels of enantioselectivity (74–77%). Methylene cyclohexane gave excellent results, furnishing the [2 + 2] cycloaddition product 31 in 70% yield and 94% e.e. as a single diastereoisomer. On the other hand, carrying out the reaction in presence of electron-poor olefins such as methyl acrylate provided the corresponding cycloadduct in a lower yield of 30%, with very high stereocontrol (88% e.e.) as a single diastereoisomer (32; Fig. 4a). We next performed the reaction with the natural compound (R)-(–)-carvone. Interestingly, the corresponding product formed in 45% yield as a 1.5:1 mixture of diastereoisomers. Both cycloadducts could be isolated, providing access to complex structures featuring four contiguous stereogenic centres along with two contiguous all-carbon quaternary stereogenic centres (33 and 33′; Fig. 4a). Finally, we carried out a series of synthetic manipulations on the optically active cycloadduct 6 to demonstrate that the polycyclic scaffold can be further manipulated (Fig. 4b). It was possible to transform the aldehyde moiety either into a carboxylic acid (product 34 in 68% yield and 92% e.e.) or a terminal alkyne (35 in 55% yield and 92% e.e.): two privileged functionalities for bioconjugation processes. Alternatively, the concomitant reduction of the amide and the aldehyde group rendered product 36 in 64% yield and 91% e.e.

a, Intermolecular enantioselective [2 + 2] cycloadditions with external olefins. b, Synthetic elaborations of the optically active cycloadduct. From top to bottom: Pinnick oxidation, Corey–Fuchs homologation and concomitant reduction of amide and aldehyde functionalities. Upon acid wash to remove the organocatalyst, the crude product of the photochemical reaction was used directly in the subsequent transformation without any further purification. The yield of the synthetic elaborations was measured on the basis of 1H NMR analysis to determine the amount of cycloadduct 6 used as the starting material.

Conclusions

We have shown that structural modifications of iminium ions can lead to previously inaccessible reactivities. Their T1 state enabled an organocatalytic enantioselective [2 + 2] photocycloaddition, which proceeds in the absence of any external photocatalyst. Using UV–vis and transient spectroscopy, we established that the triplet state of the iminium ion is the key reactive intermediate in this transformation. The proposed reaction pathway was further supported by DFT calculations, which revealed a singlet–triplet intersystem crossing (S1 → T2) facilitating access to the reactive T1 state. The generality of the process was demonstrated across a range of substrates bearing diverse functional groups, affording the desired products in consistently high yields and with excellent enantioselectivities. Moreover, the catalytic system was successfully extended to the intermolecular variant of the reaction, including complex alkene partners such as (R)-(–)-carvone. These findings establish an alternative platform in the field of catalytic asymmetric dearomatization reactions harnessing excited-state reactivity.

Methods

General procedure for the intramolecular preparation of enantioenriched cycloadducts

A 4-ml screw-cap vial equipped with a magnetic stirring bar was charged with the indole substrate (1 equiv.) and organocatalyst 2d (20 mol%) and filled with argon. Then, CHCl3 (0.25 M) was added after being dried with 4-Å molecular sieves and degassed by sparging argon for 10 min. TFA was added (2.5 equiv.), and the vial was sealed. The mixture was irradiated until full consumption of the starting material with a Kessil lamp set at 50% of its maximum output power, unless otherwise stated. Then, the solvent was evaporated and the crude product was subjected to 1H NMR analysis to determine the NMR yield and the d.r. value. Afterwards, the crude product of the reaction was dissolved in CH2Cl2 (0.25 M), and ethyl(triphenylphosphoranylidene)acetate (2.5 equiv.) was added. After stirring for 16 h, the crude mixture was directly purified by column chromatography on silica gel. The products were obtained as an inseparable mixture of E and Z isomers deriving from the Wittig derivatization. The enantiomeric excess was determined by ultra-performance convergence chromatography (UPC2) analysis on the chiral stationary phase. For the preparation of the racemic products, see ‘General procedure D’ in Supplementary Information.

General procedure for the intermolecular preparation of enantioenriched cycloadducts

A 4-ml screw-cap vial equipped with a magnetic stirring bar was charged with the indole substrate (1 equiv.), the organocatalyst 2d (20 mol%) and the appropriate olefin (3 equiv.) and filled with argon. Then, CHCl3 (0.25 M) was added after being dried with 4-Å molecular sieves and degassed by sparging argon for 10 min. TFA was added (2.5 equiv.), and the vial was sealed. The mixture was irradiated for 18 h with a Kessil lamp set at 50% of its maximum output power, unless otherwise stated. Then, the solvent was evaporated and the crude product was subjected to 1H NMR analysis to determine the NMR yield and the d.r. value. The crude mixture was directly purified by column chromatography on silica gel, affording the desired products. The enantiomeric excess was determined by UPC2 analysis on chiral stationary phase. For the preparation of the racemic products, see ‘General procedure F’ in Supplementary Information.

Data availability

Details about materials, methods, experimental procedures, mechanistic studies, characterization data and NMR spectra are available in Supplementary Information. All calculations are provided electronically in the ioChem-BD Computational Chemistry repository at https://doi.org/10.19061/iochem-bd-6-426 (ref. 41). Crystallographic data for the structure reported in this article have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre under deposition no. CCDC 2392077 (14). Copies of the data are available via the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre at https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures.

References

Dalko, P. I. (ed.) Comprehensive Enantioselective Organocatalysis: Catalysts, Reactions, and Applications (Wiley-VCH, 2013).

MacMillan, D. W. C. The advent and development of organocatalysis. Nature 455, 304–308 (2008).

Erkkilä, A., Majander, I. & Pihko, P. M. Iminium catalysis. Chem. Rev. 107, 5416–5470 (2007).

Mariano, P. S. The photochemistry of iminium salts and related heteroaromatic systems. Tetrahedron 39, 3845–3879 (1983).

Mariano, P. S. Electron-transfer mechanisms in photochemical transformations of iminium salts. Acc. Chem. Res. 16, 130–137 (1983).

Cai, X., Chang, V., Chen, C., Kim, H.-J. & Mariano, P. S. A potentially general method to control relative stereochemistry in enone–olefin 2+2-photocycloaddition reactions by using eniminium salt surrogates. Tetrahedron Lett. 41, 9445–9449 (2000).

Chen, C., Chang, V., Cai, X., Duesler, E. & Mariano, P. S. A general strategy for absolute stereochemical control in enone-olefin [2 + 2] photocycloaddition reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 6433–6434 (2001).

Silvi, M. & Melchiorre, P. Enhancing the potential of enantioselective organocatalysis with light. Nature 554, 41–49 (2018).

Arceo, E., Jurberg, I., Álvarez-Fernández, A. & Melchiorre, P. Photochemical activity of a key donor–acceptor complex can drive stereoselective catalytic α-alkylation of aldehydes. Nat. Chem 5, 750–756 (2013).

Silvi, M., Verrier, C., Rey, Y., Buzzetti, L. & Melchiorre, P. Visible-light excitation of iminium ions enables the enantioselective catalytic β-alkylation of enals. Nat. Chem. 9, 868–873 (2017).

Zou, Y.-Q., Hörmann, F. M. & Bach, T. Iminium and enamine catalysis in enantioselective photochemical reactions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 47, 278–290 (2018).

Rigotti, T., Mas-Ballesté, R. & Alemán, J. Enantioselective aminocatalytic [2 + 2] cycloaddition through visible light excitation. ACS Catal. 10, 5335–5346 (2020).

Hörmann, F. M., Chung, T. S., Rodriguez, E., Jakob, M. & Bach, T. Evidence for triplet sensitization in the visible-light-induced [2+2] photocycloaddition of eniminium ions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 827–831 (2018).

Hörmann, F. M. et al. Triplet energy transfer from ruthenium complexes to chiral eniminium ions: enantioselective synthesis of cyclobutanecarbaldehydes by [2+2] photocycloaddition. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 9659–9668 (2020).

Brimioulle, R. & Bach, T. Enantioselective Lewis acid catalysis of intramolecular enone [2+2] photocycloaddition reactions. Science 342, 840–843 (2013).

Du, J., Skubi, K. L., Schultz, D. M. & Yoon, T. P. A dual-catalysis approach to enantioselective [2 + 2] photocycloadditions using visible light. Science 344, 392–396 (2014).

Blum, T. R., Miller, Z. D., Bates, D. M., Guzei, I. A. & Yoon, T. P. Enantioselective photochemistry through Lewis acid–catalyzed triplet energy transfer. Science 354, 1391–1395 (2016).

Yoon, T. P. Photochemical stereocontrol using tandem photoredox−chiral Lewis acid catalysis. Acc. Chem. Res. 49, 2307–2315 (2016).

Poplata, S., Tröster, A., Zou, Y.-Q. & Bach, T. Recent advances in the synthesis of cyclobutanes by olefin [2+2] photocycloaddition reactions. Chem. Rev. 116, 9748–9815 (2016).

Genzink, M. J., Kidd, J. B., Swords, W. B. & Yoon, T. P. Chiral photocatalyst structures in asymmetric photochemical synthesis. Chem. Rev. 122, 1654–1716 (2022).

Cox, B., Booker-Milburn, K. I., Elliott, L. D., Robertson-Ralph, M. & Zdorichenko, V. Escaping from flatland: [2 + 2] photocycloaddition; conformationally constrained sp3-rich scaffolds for lead generation. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 10, 1512–1517 (2019).

El-Sayed, M. A. Triplet state. Its radiative and nonradiative properties. Acc. Chem. Res. 1, 8–16 (1968).

James, M. J., Schwarz, J. L., Strieth-Kalthoff, F., Wibbeling, B. & Glorius, F. Dearomative cascade photocatalysis: divergent synthesis through catalyst selective energy transfer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 8624–8628 (2018).

Hu, N. et al. Catalytic asymmetric dearomatization by visible-light-activated [2+2] photocycloaddition. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 6242–6246 (2018).

Stegbauer, S., Jandl, C. & Bach, T. Enantioselective Lewis acid catalyzed ortho photocycloaddition of olefins to phenanthrene-9-carboxaldehydes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 14593–14596 (2018).

Ma, J. et al. Photochemical intermolecular dearomative cycloaddition of bicyclic azaarenes with alkenes. Science 371, 1338–1345 (2021).

Großkopf, J., Kratz, T., Rigotti, T. & Bach, T. Enantioselective photochemical reactions enabled by triplet energy transfer. Chem. Rev. 122, 1626–1653 (2022).

Strieth-Kalthoff, F., James, M. J., Teders, M., Pitzera, L. & Glorius, F. Energy transfer catalysis mediated by visible light: principles, applications, directions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 47, 7190–7202 (2018).

Zhu, M., Zheng, C., Zhang, X. & You, S.-L. Synthesis of cyclobutane-fused angular tetracyclic spiroindolines via visible-light-promoted intramolecular dearomatization of indole derivatives. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 2636–2644 (2019).

Oderinde, M. S. et al. Synthesis of cyclobutane-fused tetracyclic scaffolds via visible-light photocatalysis for building molecular complexity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 3094–3103 (2020).

Zhang, Z. et al. Photocatalytic intramolecular [2 + 2] cycloaddition of indole derivatives via energy transfer: a method for late-stage skeletal transformation. ACS Catal. 10, 10149–10156 (2020).

Oderinde, M. S. et al. Photocatalytic dearomative intermolecular [2 + 2] cycloaddition of heterocycles for building molecular complexity. J. Org. Chem. 86, 1730–1747 (2021).

Zhu, M., Zhang, X., Zheng, C. & You, S.-L. Energy-transfer-enabled dearomative cycloaddition reactions of indoles/pyrroles via excited-state aromatics. Acc. Chem. Res. 55, 2510–2525 (2022).

Oderinde, M. S. et al. Advances in the synthesis of three-dimensional molecular architectures by dearomatizing photocycloadditions. Tetrahedron 103, 132087 (2022).

Sun, N. et al. Enantioselective [2+2]-cycloadditions with triplet photoenzymes. Nature 611, 715–720 (2022).

Wang, J. et al. Enantioselective [2 + 2] photocycloreversion enables de novo deracemization synthesis of cyclobutanes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 22840–22849 (2024).

Inanaga, K., Takasu, K. & Ihara, M. Rapid assembly of polycyclic substances by a multicomponent cascade (4 + 2)−(2 + 2) cycloadditions: total synthesis of the proposed structure of paesslerin A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 1352–1353 (2004).

Chung, H. M., Chen, Y. H., Lin, M. R., Su, J. H. & Wang, W. H. Rumphellaone A, a novel caryophyllane-related derivative from the gorgonian coral Rumphella antipathies. Tetrahedron Lett. 51, 6025–6027 (2010).

Shen, J. et al. Apalutamide efficacy, safety and wellbeing in older patients with advanced prostate cancer from phase 3 randomised clinical studies TITAN and SPARTAN. Br. J. Cancer 130, 73–81 (2024).

Álvarez-Moreno, M. et al. Managing the computational chemistry big data problem: the ioChem-BD platform. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 55, 95–103 (2015).

Serapian, S. A. Iminium-ion-2+2-photocycloaddition. ioChem-BD https://doi.org/10.19061/iochem-bd-6-426 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Ministero dell’Università PRIN 2020927WY3 (M.N. and L.D.), PRIN2022PNRR23_01 (L.D.) and European Research Council Starting Grant 2021 SYNPHOCAT 101040025 (L.D.). Chiesi Farmaceutici SpA and Dr Davide Balestri are acknowledged for support with the D8 Venture X-ray equipment. V.C. acknowledges financial support from the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation programme under Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement PHOTO-STEREO no. 101106125. At the University of Pavia, S.A.S. thanks G. Colombo and the eos interdepartmental high performance computing facility for technical support and allocation of computational resources. S.A.S. also acknowledges D. Ravelli (University of Pavia) as well as P. García-Jambrina (University of Salamanca) and S. Gómez-Rodríguez (Autonomous University of Madrid) for very helpful discussions. Thanks are also due to I. Funes-Ardoiz (University of La Rioja) for assistance with the easyMECP.py code. We gratefully acknowledge the technical support units at the Department of Chemical Sciences of the University of Padova.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

V.C. conceived of the project and devised the experiments with L.D. V.C., G.S. and L.R. carried out the reactions and isolated and characterized the products. V.C., G.S., L.R. and L.D. rationalized the experimental results. M.N. performed the spectroscopic investigations using transient absorption spectroscopy. S.A.S. performed the DFT and TD-DFT calculations. G.P. performed the X-ray analysis. V.C. and L.D. wrote the paper with contributions from all the authors. L.D. directed the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Chemistry thanks Martins Oderinde and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–41, Discussion, general procedures A–F, Tables 1–3 and Scheme 1.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Corti, V., Simionato, G., Rizzo, L. et al. Triplet state reactivity of iminium ions in organocatalytic asymmetric [2 + 2] photocycloadditions. Nat. Chem. 18, 189–197 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41557-025-01960-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41557-025-01960-3