Abstract

Vinylene-linked two-dimensional (2D) conjugated covalent organic frameworks, or 2D poly(arylene vinylene)s (2D PAVs), are promising polymer semiconductors for (opto-)electronics, photocatalysis and electrochemistry. However, conventional solvothermal synthesis often produces 2D PAVs that are poorly crystalline or difficult to access. Here we introduce a Mannich-elimination strategy that converts 8 2D imine-covalent organic frameworks into 11 highly crystalline 2D PAVs though a reversible C=C bond formation mechanism enabling precise crystallization control. This versatile approach affords robust 2D PAVs with honeycomb, square or kagome lattices, specific surface area up to ∼2,000 m2 g−1 and lattice-mismatch tolerance up to 3.5%. High-resolution transmission electron microscopy and continuous rotation electron diffraction reveal molecular-level ordering in a 2-µm-sized triphenylbenzene-based single-crystalline 2D PAV. We demonstrate that crystallinity profoundly influences charge transport, with benzotrithiophene-based 2D PAVs exhibiting charge mobilities tenfold higher than their amorphous analogues or 2D polyimine precursors. This work establishes a general route to highly crystalline 2D conjugated polymer materials for robust applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Two-dimensional conjugated covalent organic frameworks (2D c-COFs)1,2,3,4, or layer-stacked5,6,7, crystalline 2D conjugated polymers8,9, represent a unique class of organic 2D crystals with extended in-plane π-conjugation10 and out-of-plane electronic couplings11. Typical 2D c-COFs are in-plane interconnected12,13 by conjugated linkages such as imine14,15,16,17 and pyrazine11. However, the polarized C=N bonds18,19 hinder efficient π-electron delocalization, often leading to large optical band gaps and inefficient charge carrier transport. Recent advances in vinylene- or sp2-carbon-linked 2D c-COFs20,21, that is, layered 2D poly(arylene vinylene)s (2D PAVs)22, have demonstrated significantly enhanced π-conjugation compared with imine-linked 2D c-COFs (also known as 2D polyimines, 2D PIs)23. Benefitting from their tunable topologies24,25, tailored electronic structures26, intrinsic charge carrier mobilities8,22 and abundant active sites27, these materials have attracted considerable attention in applications in (opto-)electronics10,28, photocatalysis23,26,29,30,31 and electrochemistry32.

Since the first report of crystalline 2D PAV via Knoevenagel 2D polycondensation20,21, various synthetic methodologies, including Aldol-type33,34,35, Horner–Wadsworth–Emmons36, Wittig37 or Claisen–Schmidt38 2D polycondensation reactions, have been developed to construct this class of materials. However, the achieved domain sizes via these methods are generally below 20 nm, limiting their potential in wide-scope applications. Moreover, unlike the excellent generality of the well-established Schiff-base 2D polycondensation39,40,41,42, only selected 2D PAVs are crystalline, owing to the considerably lower reversibility of C=C bond formation compared with C=N bond formation. In this context, it remains highly challenging to synthesize 2D PAVs with robust topologies and high crystallinity (for example, domain size >100 nm), which requires a deep understanding of reaction kinetics and precise control over reaction reversibility.

Here, we introduce a Mannich-elimination reaction strategy to synthesize 11 highly crystalline or single-crystalline 2D PAVs in honeycomb, square or kagome lattice structures from the 2D PI precursors. By contrast, the conventional Knoevenagel reaction approach only produces amorphous polymers for some of these systems. The cascade Mannich-elimination reaction mechanism is elucidated through model reactions at the (supra)molecular level and density functional theory (DFT) calculations. The successful synthesis of 2D PAVs is demonstrated by various ex situ spectroscopic techniques, powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) and high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HR-TEM). The molecular-level structure of a 2-µm-sized single-crystalline honeycomb 2D PAV (2DPAV-DMP-TPB, where DMP is dimethoxybenzene and TPB is triphenylbenzene) is resolved by HR-TEM and continuous rotation electron diffraction (cRED). It is noteworthy that the Mannich-elimination shows a certain lattice-mismatch tolerance (up to 3.5%) between 2D PAV and its 2D PI precursor. The specific surface areas of these 2D PAVs can be more than 100 times greater than those produced by the traditional Knoevenagel reaction. We further demonstrate that the crystallinity has a large impact on the charge transport properties, as exemplified by benzotrithiophene (BTT)-based honeycomb 2D PAVs, which exhibit charge mobilities ten times greater than the amorphous 2D PAV and their corresponding 2D PIs. This work opens an avenue for the efficient synthesis of highly crystalline 2D PAVs, suitable for robust applications.

Results and discussion

Model compounds and 2D PAVs by Mannich-elimination reaction

The Mannich reaction has been widely utilized in the synthesis of bioactive compounds43. When combined with the elimination process, the Mannich-elimination reaction (also known as retro-Michael addition-elimination reaction) enables facile C=C bond formation using either a base (for example, KOH) or a Lewis acid (for example, In(OTf)3) as a catalyst44. To assess the feasibility of this reaction for synthesizing 2D PAVs, we investigated the reaction mechanism through a series of model reactions and DFT calculations. In a representative model reaction, the Mannich-elimination reaction between (E)-N,1-diphenylmethanimine (1) and 2-(4-(tert-butyl)phenyl)acetonitrile (2) involves a two-step process (Fig. 1a,b): C–C bond formation between the imine and the active methylene to generate the intermediate addition product 5, followed by the elimination process towards the formation of the cyano-vinylene bond in (Z)-2-(4-(tert-butyl)phenyl)-3-phenylacrylonitrile (3) with aniline (4) as the by-product.

a, Schematic synthesis of model compound 3. (i) Cs2CO3, DMAc/H2O (10/1), 120 °C, 8 h. b, Proposed reaction mechanism for the Mannich-elimination pathway. c, In situ NMR analysis of model reaction performed in DMAc. The spectra of compounds 1, 2 and 4 measured in DMSO-d6 are shown for comparison. The in situ spectra are recorded in DMAc with trace DMSO-d6 for calibration. d, Schematic synthesis of 2DPAV-BTT-P(F) and 2DPAV-TPB-P(F) from the F-labelled 2D PIs. (ii) Cs2CO3, DMAc/H2O (7/3), 120 °C, 5–6 days. e,f, Time-dependent solid-state 13C CP NMR (e) and FT-IR (f) spectra during the synthesis of 2DPAV-BTT-P(F) (lines for 6 days) from 2DPI-BTT-P(F) (lines for 0 days).

Aiming to optimize the reaction reactivity, we performed the model reaction in a mixed solvent of dimethylacetamide (DMAc)/H2O (v/v = 10/1) at 120 °C for 8 h under different catalytic conditions (2 equivalents of catalyst per C=N bond; see the synthetic details in the Supplementary Information). The results suggest that compound 3 can be obtained in 10–35% yield in the presence of mild bases such as NaOAc, KOAc, CsOAc, Na2CO3 and K2CO3. However, the yield significantly increases when using KOH (86%) or Cs2CO3 (98%) as a catalyst. By contrast, only hydrolysis of 1 occurs, and no product 3 was detected under acidic conditions (see the results for acids and other (in)organic bases in Supplementary Table 1). We further explored the role of the solvent under optimal conditions. The results reveal that mere DMAc (98%) and 1,3-dimethyl-2-imidazolidinone (91%) efficiently promote the reaction. At the same time, other polar solvents (for example, acetonitrile and dimethylformamide) provide yields ranging from 18% to 60%, while low-polar solvents (for example, dioxane and mesitylene) hinder the reaction with a yield less than 1%.

To clarify whether the reaction follows a Mannich-elimination mechanism or a pathway involving imine hydrolysis to an aldehyde and subsequent Knoevenagel condensation, we performed in situ 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) analysis using Cs2CO3 as the catalyst and DMAc/H2O as the solvent. The spectra display a decreased intensity of the imine (1) and cyano-methylene (2) protons at 8.6 ppm and 3.9 ppm, respectively, as accompanied by the gradual appearance of the amine proton (4) at 5.0 ppm over 240 min (Supplementary Fig. 1; see also Fig. 1c). However, no aldehyde signal was observed, indicative of the cascade Mannich-elimination reaction pathway. This is further verified by the synthesis of compound 3 in 98% yield in DMAc without the addition of H2O, which excludes the hydrolysis of imine (Supplementary Table 1). The reaction is largely facilitated in DMAc compared with that in DMAc/H2O (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3), probably due to reduced reversibility of the C=C bond formation in the absence of water.

Moreover, the formation of the intermediate addition product 5 was detected by 1H NMR with characteristic cyano-C–H (ref. 45) proton signal at 4.06 ppm observed after 30 min of reaction, which fully disappeared after 120 min owing to the formation of product 3 (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 2; the 1H and 13C NMR spectra of isolated 5 are shown in Supplementary Fig. 4). The intermediate 5 was further verified by various mass spectrometry analyses (Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6), which supports our proposed reaction mechanism in Fig. 1b. This mechanism is further elucidated by DFT calculations on the relative Gibbs energy. When only DMAc is used as the solvent, the formation of 5 is energetically very favourable (Supplementary Fig. 7), while its transformation into the key transition state (TS2 in Fig. 1b) during the elimination process is the rate-determining step of the reaction. In comparison, the presence of water results in relatively sluggish reaction kinetics for the formation of the TS1 transition state in the Mannich step, accounting for the experimentally observed slower reactions. The presence of water is expected to improve the reversibility of C=C bond formation, which is essential for achieving high structural ordering in 2D PAVs. Meanwhile, water does not affect the calculated energy barriers for the formation of TS2 (Supplementary Fig. 7).

We thus envision that the Mannich-elimination reaction between crystalline 2D PIs and symmetric acetonitrile monomers would lead to 2D PAVs with a well-maintained structural order of the 2D PI precursors. To probe this hypothesis, we synthesized two F-labelled crystalline 2D PIs, that is, 2DPI-BTT-P(F) (P = phenyl; all polymers in this work are named A–B–C, where A is 2DPI or 2DPAV, B is the aldehyde building block and C is the amine or methylene building block) and 2DPI-TPB-P(F), via Schiff-base polycondensation in solvothermal syntheses. Then, we monitored their transformation with the C2-symmetric 1,4-phenylenediacetonitrile into 2DPAV-BTT-P(F) and 2DPAV-TPB-P(F) (Fig. 1d) by solid-state 19F/13C cross-polarization (CP) NMR and Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopies. Taking 2DPAV-BTT-P(F) as an example, the ex situ 13C CP NMR spectra show peaks at 57 and 30 ppm for the isolated polymers after 1 day of synthesis, which correspond to the formation of the intermediate addition product (Fig. 1e and Supplementary Fig. 8). These peaks gradually vanish over 6 days, accompanied by the disappearance of the C=N signal at 157 ppm for 2DPI-BTT-P(F) and the appearance of a cyano-vinylene peak at 117 and 108 ppm. The solid-state 19F NMR spectra show no 19F peak in the resultant 2DPAV-BTT-P(F) (Supplementary Fig. 9), indicative of complete consumption of 2DPI-BTT-P(F) after the synthesis. Ex situ FT-IR spectra show that the stretching vibration of the imine bond at 1,597 cm−1 gradually shifts to 1,590 cm−1 (C=C) owing to the formation of cyano-vinylene linkages in 2DPAV-BTT-P(F) (Fig. 1f and Supplementary Fig. 10). In addition, the C≡N peak is observed at 2,214 cm−1. The solid-state 19F/13C CP NMR and FT-IR spectra of 2DPAV-TPB-P(F) are shown in Supplementary Figs. 9 and 11.

Highly crystalline 2D PAVs in different lattices by Mannich-elimination reaction

Encouraged by the above results, we synthesized the unlabelled powder-based 2DPI-BTT-P and 2DPI-TPB-P, which exhibit dark-yellow and light-yellow colours (Fig. 2), respectively. They display enhanced crystallinity compared with F-labelled 2D PIs (Supplementary Fig. 12) due to the high symmetry of the unlabelled building block, which would result in better layer stacking. Using the above Mannich-elimination approach, 2DPAV-BTT-P and 2DPAV-TPB-P were subsequently obtained as red and light-yellow powders, respectively (Fig. 2; see their FT-IR, Raman and ultraviolet–visible (UV–vis) absorption spectra as well as scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images in Supplementary Figs. 13–19; the PXRD pattern of 2DPAV-TPB-P, 2DPAV-TPB-P(F) and their 2D PIs is shown in Supplementary Fig. 20). PXRD analysis reveals the crystalline nature of 2DPAV-BTT-P with distinct 2θ signals at 3.45° (corresponding to 2.56 nm), 6.03°, 7.00°, 9.42°, 12.16° and 25.25° (Fig. 3a, red line), which we assign to the (100), (110), (200), (210), (220) and (001) crystallographic planes, respectively, for an AA stacking geometry (see the Pawley refinement in Supplementary Fig. 21). The full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the (001) peak is determined to be 0.39°. As expected, 2DPAV-BTT-P(F) exhibits similar PXRD signals but with a larger FWHM value of 0.55° (Fig. 3a, brown line), indicative of an inferior crystallinity in the material derived from the F-labelled 2D PI. In stark contrast, the directly synthesized sample, namely 2DPAV-BTT-P(Kn), through Knoevenagel polycondensation between benzo[1,2-b:3,4-b′:5,6-b″]trithiophene-2,5,8-tricarbaldehyde and 1,4-phenylenediacetonitrile is amorphous. It is also noted that performing the Mannich-elimination reaction on 2DPI-TPB-P in the absence of water does not lead to the expected 2DPAV-TPB-P, further highlighting the critical role of water in enhancing the reaction reversibility towards crystalline materials.

a–c, PXRD patterns (a), N2 physisorption isotherms (b) and pore size distributions (c) for 2DPI-BTT-P (black), 2DPAV-BTT-P (olive), 2DPAV-BTT-P(F) (orange) and 2DPAV-BTT-P(Kn) (light violet). d–f, PXRD patterns (d), N2 physisorption isotherms (e) and pore size distributions (f) for 2DPI-BTT-BP (black), 2DPAV-BTT-BP (olive), 2DPAV-BTT-BPY (dark red), 2DPAV-BTT-BT (cyan), 2DPAV-DMP-TPB (dark violet) and 2DPAV-HATN-P (light violet).

HR-TEM imaging shows the well-defined honeycomb lattice of 2DPAV-BTT-P (Supplementary Fig. 22). N2 physisorption measurements were further performed to elucidate the pore characteristics of the polymer frameworks. Both 2DPI-BTT-P and 2DPAV-BTT-P show type I isotherms, with Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) surface areas of 2,061 m2 g−1 and 1,844 m2 g−1, respectively. By contrast, the amorphous 2DPAV-BTT-P(Kn) exhibits a surface area as small as 16 m2 g−1 (Fig. 3b). The pore size distribution calculated by the non-local DFT method reveals a pore diameter reduction from 2.8 nm in 2DPI-BTT-P to 2.4 nm in 2DPAV-BTT-P attributable to the presence of cyano groups in the pore channels of the latter (Fig. 3c; see more details in Supplementary Figs. 23 and 24). These results support our strategy for constructing highly crystalline 2D PAVs, especially those that cannot be directly synthesized by Knoevenagel polycondensation, via the Mannich-elimination reaction on well-defined 2D PIs.

To explore the universality of this strategy, we first synthesized 2DPAV-BTT-DMP from 2DPI-BTT-P and 2,2′-(2,5-dimethoxy-1,4-phenylene)diacetonitrile (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 25). We further extended the approach to obtain 2DPI-BTT-BP (BP = biphenyl) and then 2DPAV-BTT-BP with an enlarged lattice parameter. More interestingly, by using 2,2′-([2,2′-bipyridine]-5,5′-diyl)diacetonitrile and 2,2′-([2,2′-bithiophene]-5,5′-diyl)diacetonitrile, which share a similar core length to 2,2′-([1,1′-biphenyl]-4,4′-diyl)diacetonitrile, we synthesize a series of BTT-based 2D PAVs with distinct electronic structures from 2DPI-BTT-BP (yellow powders) via the Mannich-elimination reaction: 2DPAV-BTT-BP (in light-orange colour), 2DPAV-BTT-BPY (in dark-orange colour; BPY = bipyridine) and 2DPAV-BTT-BT (in dark-brown colour; BT = bithiophene) as depicted in Fig. 2. The successful synthesis of materials is demonstrated by FT-IR and solid-state 13C CP NMR, as well as Raman spectroscopies (Supplementary Figs. 26–29). The experimental Raman spectra are nicely reproduced by theoretical calculations, which indicate a gradual shift of the C=C stretching vibration from 1,585 cm−1 in 2DPI-BTT-BP to 1,438–1,583 cm−1 for the 2D PAVs due to enhanced 2D conjugation (see more detailed discussion in Supplementary Fig. 29). DFT calculations reveal dihedral angles between the C2 building block and the vinylene linkage (Supplementary Figs. 30–32) following the sequence of 2DPI-BTT-BP (ca. 30°) > 2DPAV-BTT-BP > 2DPAV-BTT-BPY > 2DPAV-BTT-BT (smaller than 5°). These results highlight the high feasibility of finely tuning the chemical and electronic structures of 2D conjugated polymers using the Mannich-elimination synthetic strategy.

The lattice mismatch (LM) between 2DPI-BTT-BP and the 2D PAVs can be tolerated up to 3.5% (Fig. 2), and 2DPAV-BTT-BP, 2DPAV-BTT-BPY and 2DPAV-BTT-BT are highly crystalline, while the directly synthesized materials are amorphous (Supplementary Figs. 33–35). PXRD patterns display that the (100) peak of 2DPI-BTT-BP shifts from 2.80° (corresponding to 3.15 nm) to 2.79°, 2.76° and 2.90° for the BP/BPY/BT-bridged 2D PAVs, respectively (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. 36); the FWHM value changes slightly from 0.25° to 0.27°, 0.26° and 0.28°, respectively. We further studied the role of LM by synthesizing 2DPAV-BTT-BP(LM) from 2DPI-BTT-P and 2DPAV-BTT-P(LM) from 2DPI-BTT-BP (LM degree of ca. 19%). The former vinylene-linked polymer is amorphous, while the latter shows considerably inferior crystallinity to that of 2DPAV-BTT-P (Supplementary Fig. 37). These results imply that, to achieve a high structural order in 2D PAV, the acetonitrile monomers need to penetrate the porous channels of the 2D PI, followed by the Mannich-elimination reaction at specific imine sites, without causing much lattice expansion or contraction.

The simulated PXRD pattern and SEM images of 2DPAV-BTT-BP, 2DPAV-BTT-BPY and 2DPAV-BTT-BT are shown in Supplementary Figs. 38–41. Their honeycomb polymer frameworks are resolved by HR-TEM images. The distances between adjacent pore centres are 3.1, 3.1 and 2.9 nm, respectively (Supplementary Figs. 42–44), which are consistent with the PXRD results. Their BET surface areas estimated from N2 physisorption isotherms are 1,985, 897 and 622 m2 g−1, respectively; 2DPI-BTT-BP shows a surface area of 2,134 m2 g−1 (Fig. 3e). It should be noted that the specific surface area of 1,985 m2 g−1 achieved for 2DPAV-BTT-BP represents the record value for the reported 2D PAVs, emphasizing the critical importance of crystallinity. Similar to the above BTT/P-based system, changing from 2DPI-BTT-BP (3.5 nm) to 2D PAVs also results in a pore size reduction to 3.1 (BP), 3.2 (BPY) and 2.9 (BT) nm (Fig. 3f).

As shown in Fig. 4a, the Mannich-elimination synthetic strategy is also powerful for the synthesis of three other highly crystalline 2D PAVs in honeycomb, square or kagome lattice based on C2-symmetric acetonitrile monomers, that is, 2DPAV-TPT-P (TPT = triphenyltriazine; in yellow colour), 2DPAV-TPPy-P (TPPy = tetraphenylpyrene; in orange colour) and 2DPAV-HATN-P (HATN = hexaazatrinaphthalene; in yellow colour). It is significant that their BET surface areas are nearly twice those of the 2D PAVs directly synthesized via the Knoevenagel approach (Supplementary Figs. 45 and 46). Our synthetic strategy can be further extended to construct 2D PAVs based on C3-symmetric acetonitrile building blocks46,47. For instance, honeycomb 2DPAV-P-TPB and 2DPAV-DMP-TPB were successfully synthesized as yellow and dark-orange powders, respectively, from 2,2′-(5′-(4-(cyanomethyl)phenyl)-[1,1′:3′,1″-terphenyl]-4,4″-diyl)diacetonitrile (Fig. 4b). However, transformation of a C3-symmetric building block is more challenging, requiring harsher synthetic conditions—specifically, 8 equivalents of base per C=N bond at 130 °C for 12 days—to achieve full conversion. The characterization of the above five materials by PXRD, solid-state 13C CP NMR, FT-IR and Raman, along with related theoretical calculations, is shown in Fig. 3d and Supplementary Figs. 47–52.

a, Honeycomb, square and kagome 2D PAVs synthesized from 2D PIs and C2-symmetric acetonitrile monomers. (i) Cs2CO3, 120–130 °C, DMAc/H2O, 6–8 days. b, Honeycomb 2D PAVs synthesized from 2D PIs and C3-symmetric acetonitrile monomers. (ii) Cs2CO3, 120–130 °C, DMAc/H2O, 6–12 days. The pictures within each of the structures are photos of the powder obtained.

Single-crystalline 2D PAV by Mannich-elimination reaction

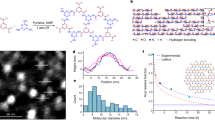

We further demonstrated the synthesis of single-crystalline 2DPI-DMP-TPB under solvothermal conditions48. Optical, SEM and TEM images reveal a flake-like morphology for the hexagonal 2D PI crystals, with domain sizes exceeding 2 μm (Supplementary Figs. 53–55). After the Mannich-elimination transformation, the resulting 2DPAV-DMP-TPB crystal can maintain the hexagonal morphology of the 2D PI precursor showing a domain size of approximately 2 μm (Supplementary Figs. 56 and 57) and a surface area of 1,901 m2 g−1 (Supplementary Fig. 58). HR-TEM images reveal its honeycomb polymer framework at the molecular level (Fig. 5a; see more details in Supplementary Fig. 59) with a lattice distance of 3 nm, which qualitatively agrees with the simulated structure (Fig. 5b). Supplementary Fig. 60 displays the selected area electron diffraction (SAED) patterns throughout the crystal. Although slightly tilted from the 0001 zone axis, they exhibit the same orientation, indicative of their single-crystalline nature.

a, Cs-corrected HR-TEM image along with the SAED pattern. b, Simulated HR-TEM image of selected area in a (red box). c, cRED of a hexagonal 2D PAV crystal. Inset: the crystal on a Cu grid. d, Experimental PXRD pattern (pink), Rietveld-refined profile (black) and their difference plots (dark blue). e,f, Top (e) and side (f) views of the resolved AA-serrated stacking structure.

cRED collected in low-dose mode at 99 K (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Fig. 61) revealed a hexagonal unit cell with parameters a = b = 36.55 Å, c = 7.13 Å and β = 120° for 2DPAV-DMP-TPB. To validate the crystal structure, the PXRD pattern was simulated from the cRED-derived structural model and further refined by Rietveld analysis (Fig. 5d, Supplementary Fig. 62 and Supplementary Table 2). The refined unit cell parameters are a = b = 36.505(4) Å, c = 7.094(8) Å, α = β = 90°, γ = 120°, with convergence at Rwp = 3.66% (weighted profile residual factor) and Rp = 2.47% (profile residual factor). Collectively, these results establish 2DPAV-DMP-TPB as a honeycomb-structured material adopting an AA-serrated stacking arrangement in the P6/mcc space group (Fig. 5e).

Enhanced conjugation and charge transport in crystalline 2D PAVs

To elucidate the enhanced conjugation in 2D PAV compared with that in 2D PI, we calculated the electronic band structures of monolayer 2DPI-BTT-P, 2DPI-BTT-BP, 2DPAV-BTT-P and 2DPAV-BTT-BP. The 2D PAVs show band gaps nearly 0.2 eV smaller than those of 2D PIs (Supplementary Fig. 63). All monolayers present relatively flat conduction band minima and valence band maxima (Supplementary Fig. 64) due to ineffective cross-conjugation associated with the honeycomb lattice. As shown in the zoom-in band structure (Supplementary Figs. 65 and 66) and partial charge distribution (Supplementary Fig. 67), 2DPAV-BTT-BP and 2DPAV-BTT-P present π-delocalized frontier orbitals and band dispersion intensities more than three times higher than those of the corresponding 2D PIs. UV–vis absorption spectra reveal an optical band gap reduction by approximately 0.05 and 0.2 eV for the above crystalline 2D PAVs compared with the amorphous 2D PAVs synthesized via the Knoevenagel reaction (labelled by Kn) and corresponding 2D PIs, respectively (see details in Fig. 6a and Supplementary Figs. 68 and 69).

a, UV–vis absorption spectra of 2DPI-BTT-P (light violet), 2DPAV-BTT-P (dark red), 2DPAV-BTT-P(Kn) (dark cyan), 2DPI-BTT-BP (black), 2DPAV-BTT-BP (olive) and 2DPAV-BTT-BP(Kn) (cyan). b, Time-resolved terahertz photoconductivity of 2DPAV-BTT-P (dark red), 2DPAV-BTT-P(Kn) (dark cyan), 2DPAV-BTT-BP (olive) and 2DPAV-BTT-BP(Kn) (cyan). c, Frequency-resolved complex terahertz photoconductivity for 2DPAV-BTT-BP. The solid blue and red lines represent the Drude–Smith fits describing the real and imaginary components of the complex terahertz photoconductivity, respectively. d, Comparison of charge carrier mobilities and electrical conductivities of 2DPAV-BTT-BP, amorphous 2DPAV-BTT-BP(Kn) and 2DPI-BTT-BP.

To elucidate the charge transport properties of 2D PAVs associated with conjugation and crystallinity, we measured the time-resolved photoconductivity of crystalline and amorphous 2D PAVs as well as related 2D PIs by optical-pump terahertz probe spectroscopy. As shown in Fig. 6b, 2DPAV-BTT-BP shows a photoconductivity intensity at least ten times higher than that of amorphous 2DPAV-BTT-BP(Kn), indicating that the intrinsic charge carrier mobility of crystalline 2D PAVs is at least one order of magnitude higher than their amorphous counterparts (a similar trend is observed for 2DPAV-BTT-P system). Moreover, frequency-resolved photoconductivity measurements reveal an intrinsic charge carrier mobility of approximately 10 cm2 V−1 s−1 for 2DPAV-BTT-BP, which is nearly ten times that of 2DPI-BTT-BP (the charge carrier scattering time is 56 fs for the former and 17 fs for the latter; see more details in Figs. 5f and 6c and Supplementary Figs. 70 and 71). Characterizing pellet samples using the four-probe method further demonstrates an electrical conductivity of 2DPAV-BTT-BP three times greater than that of 2DPAV-BTT-BP(Kn) (Fig. 6d). These results underscore the crucial role of π-conjugation and crystallinity in enhancing the charge transport properties of 2D c-COFs.

Discussion

In conclusion, we have developed a Mannich-elimination synthetic strategy that efficiently forms C=C bonds, as demonstrated through multiple model reactions and theoretical calculations. This approach is general to the synthesis of highly crystalline 2D PAVs in diverse lattice structures, such as honeycomb, square and kagome, derived from the 2D PI precursors. The specific surface areas of these 2D PAVs can be more than 100 times greater than those produced by the traditional Knoevenagel reaction. We resolve the honeycomb crystal structure of a single-crystalline 2D PAV at the molecular level. Our results further reveal that the crystallinity and π-conjugation of 2D PAVs significantly impact the charge carrier transport properties of 2D PAVs. This work not only deepens our understanding of 2D PAVs but also opens new avenues for crafting well-defined, conjugated, highly porous crystalline polymer materials for robust applications.

Methods

Synthesis of model compound 3 via Mannich-elimination reaction

A mixture of 1 (50 mg, 275.88 µmol), 2 (57.36 mg, 331.06 µmol), Cs2CO3 (179.77 mg, 551.76 µmol), DMAc (3 ml) and water (0.3 ml) was added to a Schlenk tube. The Schlenk tube was sealed under an inert environment and heated at 120 °C for 8 h. After the reaction, 50 ml water was added into the reaction mixture, which was then extracted with dichloromethane. The crude product was purified by silica gel chromatography using hexane/ethyl acetate = 97/3 as eluent to give 3 as a light-yellow solid in 98% yield (70 mg).

Synthesis of 2DPAV-BTT-BP

A glass ampoule was charged with 2DPI-BTT-BP (7 mg), 2,2′-([1,1′-biphenyl]-4,4′-diyl)diacetonitrile (14 mg, 2 equivalents per C=N bond), Cs2CO3 (50 mg, 4 equivalents per C=N bond) and a mixture of DMAc/H2O (0.7/0.3 ml). Afterwards, the mixture was sonicated for 10 min at room temperature, and the ampoule was degassed by three freeze–pump–thaw cycles, sealed under vacuum and heated at 130 °C for 6 days. After cooling to room temperature, the resulting powders were filtered and sequentially washed with dimethylformamide, H2O, ethanol and acetone. After Soxhlet extraction with tetrahydrofuran for 18 h, the sample was collected and dried under vacuum at 100 °C overnight, yielding 2DPAV-BTT-BP (7.4 mg) as a light-orange solid with a 96% yield. Following the same conditions, 2,2′-([2,2′-bipyridine]-5,5′-diyl)diacetonitrile (14 mg) or 2,2′-([2,2′-bithiophene]-5,5′-diyl)diacetonitrile (14 mg) was used to synthesize 2DPAV-BTT-BPY (7.4 mg, red solid) and 2DPAV-BTT-BT (7 mg, dark-brown solid) in 95% and 91% yield, respectively.

Synthesis of single-crystalline 2DPAV-DMP-TPB

A glass ampoule was charged with single-crystalline 2DPI-DMP-TPB (5 mg), 2,2′-(5′-(4-(cyanomethyl)phenyl)-[1,1′:3′,1′′-terphenyl]-4,4′′-diyl)diacetonitrile (10 mg, 1.2 equivalents per C=N bond), Cs2CO3 (50 mg, 8 equivalents per C=N bond) and a mixture of DMAc/H2O (0.5/0.1 ml). Afterwards, the mixture was sonicated for 10 min at room temperature, and the ampoule was degassed by three freeze–pump–thaw cycles, sealed under vacuum and heated at 130 °C for 12 days. After cooling to room temperature, the resulting powders were filtered and sequentially washed with dimethylformamide, H2O, ethanol and acetone. After Soxhlet extraction with acetone for 18 h, the sample was collected and dried under vacuum at 100 °C overnight to give 2DPAV-DMP-TPB (2.6 mg) as a dark-orange solid in 48% yield.

HR-TEM imaging and image simulation

Experiments were performed on an image-side spherical aberration-corrected FEI Titan 80-300 operated at 300 kV. The FEI Titan is equipped with a CEOS hexapole spherical aberration coefficient (Cs) corrector, capable of correcting geometrical axial aberrations up to the third order. The images were acquired using a Gatan UltraScan1000 CCD camera. HR-TEM image simulations were performed with the abTEM package49 using the Quantum Expresso plane-wave DFT code by using the GGA-PBE relaxed multilayer 2DPAV-DMP-TPB.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available in the Article or its Supplementary Information and are also available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request. Source data are provided with this paper. These data are also available via Figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30571898.v2 (ref. 50).

References

Ascherl, L. et al. Molecular docking sites designed for the generation of highly crystalline covalent organic frameworks. Nat. Chem. 8, 310–316 (2016).

Zhang, W. et al. Reconstructed covalent organic frameworks. Nature 604, 72–79 (2022).

Xing, G. et al. Nonplanar rhombus and kagome 2D covalent organic frameworks from distorted aromatics for electrical conduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 5042–5050 (2022).

Koner, K. & Banerjee, R. Porous polycyclic aromatic heterocycles via metal-free annulative π-extension. Nat. Synth. 3, 1266–1274 (2024).

Jin, Y., Hu, Y. & Zhang, W. Tessellated multiporous two-dimensional covalent organic frameworks. Nat. Rev. Chem. 1, 0056 (2017).

Guan, X. et al. Chemically stable polyarylether-based covalent organic frameworks. Nat. Chem. 11, 587–594 (2019).

Zhao, S. et al. Hydrophilicity gradient in covalent organic frameworks for membrane distillation. Nat. Mater. 20, 1551–1558 (2021).

Wang, M. et al. Exceptionally high charge mobility in phthalocyanine-based poly(benzimidazobenzophenanthroline)-ladder-type two-dimensional conjugated polymers. Nat. Mater. 22, 880–887 (2023).

Galeotti, G. et al. Synthesis of mesoscale ordered two-dimensional π-conjugated polymers with semiconducting properties. Nat. Mater. 19, 874–880 (2020).

Wang, Z., Wang, M., Heine, T. & Feng, X. Electronic and quantum properties of organic two-dimensional crystals. Nat. Rev. Mater. 10, 147–166 (2025).

Wang, M. et al. Unveiling electronic properties in metal–phthalocyanine-based pyrazine-linked conjugated two-dimensional covalent organic frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 16810–16816 (2019).

Zhao, W. et al. Using sound to synthesize covalent organic frameworks in water. Nat. Synth. 1, 87–95 (2022).

Zhan, G. et al. Observing polymerization in 2D dynamic covalent polymers. Nature 603, 835–840 (2022).

Jeon, J.-P. et al. Benzotrithiophene-based covalent organic framework photocatalysts with controlled conjugation of building blocks for charge stabilization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202217416 (2023).

Zhou, Z. et al. Conformational chirality of single-crystal covalent organic frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 34064–34069 (2024).

Auras, F. et al. Dynamic two-dimensional covalent organic frameworks. Nat. Chem. 16, 1373–1380 (2024).

Gruber, C. G., Frey, L., Guntermann, R., Medina, D. D. & Cortés, E. Early stages of covalent organic framework formation imaged in operando. Nature 630, 872–877 (2024).

Cusin, L., Peng, H., Ciesielski, A. & Samorì, P. Chemical conversion and locking of the imine linkage: enhancing the functionality of covalent organic frameworks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 14236–14250 (2021).

Evans, A. M. et al. Two-dimensional polymers and polymerizations. Chem. Rev. 122, 442–564 (2022).

Zhuang, X. et al. A two-dimensional conjugated polymer framework with fully sp2-bonded carbon skeleton. Polym. Chem. 7, 4176–4181 (2016).

Jin, E. et al. Two-dimensional sp2 carbon–conjugated covalent organic frameworks. Science 357, 673–676 (2017).

Liu, Y. et al. A thiophene backbone enables two-dimensional poly(arylene vinylene)s with high charge carrier mobility. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202305978 (2023).

Liu, R. et al. Linkage-engineered donor–acceptor covalent organic frameworks for optimal photosynthesis of hydrogen peroxide from water and air. Nat. Catal. 7, 195–206 (2024).

Li, S. et al. Direct construction of isomeric benzobisoxazole–vinylene-linked covalent organic frameworks with distinct photocatalytic properties. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 13953–13960 (2022).

Zhou, Z. et al. Carbon dioxide capture from open air using covalent organic frameworks. Nature 635, 96–101 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. Facile construction of fully sp2-carbon conjugated two-dimensional covalent organic frameworks containing benzobisthiazole units. Nat. Commun. 13, 100 (2022).

Bi, S. et al. Heteroatom-embedded approach to vinylene-linked covalent organic frameworks with isoelectronic structures for photoredox catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202111627 (2022).

Liu, M. et al. Two-dimensional covalent organic framework films prepared on various substrates through vapor induced conversion. Nat. Commun. 13, 1411 (2022).

Xu, S. et al. Thiophene-bridged donor–acceptor sp2-carbon-linked 2D conjugated polymers as photocathodes for water reduction. Adv. Mater. 33, 2006274 (2021).

Liu, Y. et al. Enhanced hydrogen peroxide photosynthesis in covalent organic frameworks through induced asymmetric electron distribution. Nat. Synth. 4, 134–141 (2025).

Zhang, Y., Guan, X., Meng, Z. & Jiang, H.-L. Supramolecularly built local electric field microenvironment around cobalt phthalocyanine in covalent organic frameworks for enhanced photocatalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 147, 3776–3785 (2025).

Wang, Z. et al. Green synthesis of olefin-linked covalent organic frameworks for hydrogen fuel cell applications. Nat. Commun. 12, 1982 (2021).

Jadhav, T. et al. 2D poly(arylene vinylene) covalent organic frameworks via aldol condensation of trimethyltriazine. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 13753–13757 (2019).

Lyu, H., Diercks, C. S., Zhu, C. & Yaghi, O. M. Porous crystalline olefin-linked covalent organic frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 6848–6852 (2019).

Acharjya, A., Pachfule, P., Roeser, J., Schmitt, F.-J. & Thomas, A. Vinylene-linked covalent organic frameworks by base-catalyzed aldol condensation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 14865–14870 (2019).

Pastoetter, D. L. et al. Synthesis of vinylene-linked two-dimensional conjugated polymers via the Horner–Wadsworth–Emmons reaction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 23620–23625 (2020).

Liu, Y. et al. Vinylene-linked 2D conjugated covalent organic frameworks by Wittig reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202209762 (2022).

Niu, C.-P., Zhang, C.-R., Liu, X., Liang, R.-P. & Qiu, J.-D. Synthesis of propenone-linked covalent organic frameworks via Claisen–Schmidt reaction for photocatalytic removal of uranium. Nat. Commun. 14, 4420 (2023).

Ma, T. et al. Single-crystal X-ray diffraction structures of covalent organic frameworks. Science 361, 48–52 (2018).

Banerjee, T. et al. Sub-stoichiometric 2D covalent organic frameworks from tri- and tetratopic linkers. Nat. Commun. 10, 2689 (2019).

Peng, L. et al. Ultra-fast single-crystal polymerization of large-sized covalent organic frameworks. Nat. Commun. 12, 5077 (2021).

Kang, C. et al. Growing single crystals of two-dimensional covalent organic frameworks enabled by intermediate tracing study. Nat. Commun. 13, 1370 (2022).

Arrayás, R. G. & Carretero, J. C. Catalytic asymmetric direct Mannich reaction: a powerful tool for the synthesis of α,β-diamino acids. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 1940–1948 (2009).

Selvi, T. & Velmathi, S. Indium(III) triflate-catalyzed reactions of aza-Michael adducts of chalcones with aromatic amines: retro-Michael addition versus quinoline formation. J. Org. Chem. 83, 4087–4091 (2018).

Poisson, T., Gembus, V., Oudeyer, S., Marsais, F. & Levacher, V. Product-catalyzed addition of alkyl nitriles to unactivated imines promoted by sodium aryloxide/ethyl(trimethylsilyl)acetate (ETSA) combination. J. Org. Chem. 74, 3516–3519 (2009).

Xu, H. et al. Proton conduction in crystalline and porous covalent organic frameworks. Nat. Mater. 15, 722–726 (2016).

Xu, H. et al. Stable, crystalline, porous, covalent organic frameworks as a platform for chiral organocatalysts. Nat. Chem. 7, 905–912 (2015).

Natraj, A. et al. Single-crystalline imine-linked two-dimensional covalent organic frameworks separate benzene and cyclohexane efficiently. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 19813–19824 (2022).

Madsen, J. & Susi, T. The abTEM code: transmission electron microscopy from first principles. Open Res. Eur.1, 24 (2021).

Ghouse, S. et al. Towards Single-Crystalline Two-Dimensional Poly(arylene vinylene) Covalent Organic Frameworks. Figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.30571898.v2 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by ERC Grant (T2DCP, grant no. 819698) and DFG project (CRC 1415, project no. 417590517). M.W. thanks financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 52572196). We appreciate the Materials Processing and Analysis Center at Peking University for assistance with materials characterization. We thank the Analysis and Testing Center of School of Advanced Materials, Peking University Shenzhen Graduate School and the Dresden Center for Nanoanalysis (DCN) for the use of facilities. We thank C. Zhou for assistance with terahertz measurements, and A. Waentig, R. Zhao and J. Rahimi for helpful discussions. The research at the University of Málaga was funded by the MICINN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 (Project PID2022-139548NB-I00) and by Junta de Andalucía (FQM-159). We thank the computer resources, technical expertise and assistance provided by the SCBI (Supercomputing and Bioinformatics) centre of the University of Málaga.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Max Planck Society.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.W., R.Z. and X.F. conceived and designed the project. S.G. performed most experiments and interpreted the data under the supervision of M.W. D.M., B.Z. and U.K. performed the TEM measurements. Y.F. calculated the model reactions. S.G.-V. and M.C.R.D. conducted the Raman measurements and DFT calculations for model fragments and periodic systems. S.P. and E.B. measured the solid-state NMR. L.G. and M.B. contributed to the terahertz measurements. C.H. and C.N. helped with the SEM and N2 physisorption measurements, respectively. Z.G., R.Z. and J.S. contributed to the cRED measurement and analysis. S.G., M.W., R.Z. and X.F. cowrote the manuscript with contributions from all co-authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Chemistry thanks Hong Xu, Zhenjie Zhang and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–72, Discussion and Tables 1 and 2.

Supplementary Data 1

Coordinates for the optimized structures.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

In situ NMR analysis of model reaction performed in DMAc (Fig. 1c), time-dependent solid-state 13C CP NMR (Fig. 1e) and FT-IR spectra (Fig. 1f) during the synthesis of 2DPAV-BTT-P(F) from 2DPI-BTT-P(F).

Source Data Fig. 3

PXRD pattern (Fig. 3a,d), N2 physisorption isotherms (Fig. 3b,e) and pore size distribution (Fig. 3c,f).

Source Data Fig. 5

Experimental PXRD pattern, Rietveld-refined profile and their difference plots (Fig. 5d).

Source Data Fig. 6

UV–vis absorption data (Fig. 6a), time-resolved terahertz photoconductivity data (Fig. 6b), frequency-resolved terahertz photoconductivity data (Fig. 6c) and comparison of charge carrier mobilities and electrical conductivities (Fig. 6d).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ghouse, S., Guo, Z., Gámez-Valenzuela, S. et al. Towards single-crystalline two-dimensional poly(arylene vinylene) covalent organic frameworks. Nat. Chem. (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41557-025-02048-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41557-025-02048-8

This article is cited by

-

Diketopyrrolopyrrole-based two-dimensional poly(arylene vinylene)s with high charge carrier mobility

Nature Communications (2026)