Abstract

Solar photovoltaic (PV) and wind energy provide carbon-free renewable energy to reach ambitious global carbon-neutrality goals, but their yields are in turn influenced by future climate change. Here, using a bias-corrected large ensemble of multi-model simulations under an envisioned post-pandemic green recovery, we find a general enhancement in solar PV over global land regions, especially in Asia, relative to the well-studied baseline scenario with modest climate change mitigation. Our results also show a notable west-to-east interhemispheric shift of wind energy by the mid-twenty-first century, under the two global carbon-neutral scenarios. Both solar PV and wind energy are projected to have a greater temporal stability in most land regions due to deep decarbonization. The co-benefits in enhancing and stabilizing renewable energy sources demonstrate a beneficial feedback in achieving global carbon neutrality and highlight Asian regions as a likely hotspot for renewable resources in future decades.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The ERA5 reanalysis can be obtained at https://www.ecmwf.int/en/forecasts/dataset/ecmwf-reanalysis-v5. The multi-model outputs (experiments names: historical, ssp245, ssp245-cov-strgreen and ssp245-cov-strgreen) are available at https://esgf-node.llnl.gov/search/cmip6/.

Code availability

The bias correction is based on the open-source R package of MBCn (https://rdrr.io/cran/MBC/man/MBCn.html).

References

Mukherjee, S. & Mishra, A. K. Increase in compound drought and heatwaves in a warming world. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2020GL090617 (2021).

Perkins-Kirkpatrick, S. E. & Lewis, S. C. Increasing trends in regional heatwaves. Nat. Commun. 11, 3357 (2020).

Tellman, B. et al. Satellite imaging reveals increased proportion of population exposed to floods. Nature 596, 80–86 (2021).

Yuan, X. et al. Anthropogenic shift towards higher risk of flash drought over China. Nat. Commun. 10, 4661 (2019).

Lei, Y. D. et al. Global perspective of drought impacts on ozone pollution episodes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 3932–3940 (2022).

Cai, W. J., Li, K., Liao, H., Wang, H. J. & Wu, L. X. Weather conditions conducive to Beijing severe haze more frequent under climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 7, 257–262 (2017).

Colette, A. et al. Is the ozone climate penalty robust in Europe? Environ. Res. Lett. 10, 084015 (2015).

Liu, C. et al. Ambient particulate air pollution and daily mortality in 652 cities. N. Engl. J. Med. 381, 705–715 (2019).

Vicedo-Cabrera, A. M. et al. Short term association between ozone and mortality: global two stage time series study in 406 locations in 20 countries. Br. Med. J. 368, m108 (2020).

IPCC Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5 °C (eds Masson-Delmotte, V. et al.) (WMO, 2018).

Huang, M. T. & Zhai, P. M. Achieving Paris Agreement temperature goals requires carbon neutrality by middle century with far-reaching transitions in the whole society. Adv. Clim. Change Res. 12, 281–286 (2021).

Forster, P. M. et al. Current and future global climate impacts resulting from COVID-19. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 913–919 (2020).

AlSkaif, T., Dev, S., Visser, L., Hossari, M. & van Sark, W. A systematic analysis of meteorological variables for PV output power estimation. Renew. Energy 153, 12–22 (2020).

Pryor, S. C., Barthelmie, R. J. & Schoof, J. T. Past and future wind climates over the contiguous USA based on the North American Regional Climate Change Assessment Program model suite. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 117, D19119 (2012).

Feron, S., Cordero, R. R., Damiani, A. & Jackson, R. B. Climate change extremes and photovoltaic power output. Nat. Sustain. 4, 270–276 (2020).

Gao, M. et al. Secular decrease of wind power potential in India associated with warming in the Indian Ocean. Sci. Adv. 4, eaat5256 (2018).

Gandoman, F. H., Raeisi, F. & Ahmadi, A. A literature review on estimating of PV-array hourly power under cloudy weather conditions. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 63, 579–592 (2016).

Skoplaki, E. & Palyvos, J. A. On the temperature dependence of photovoltaic module electrical performance: a review of efficiency/power correlations. Sol. Energy 83, 614–624 (2009).

Wang, J. Z., Hu, J. M. & Ma, K. L. Wind speed probability distribution estimation and wind energy assessment. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 60, 881–899 (2016).

Li, D. et al. Historical evaluation and future projections of 100‐m wind energy potentials over CORDEX‐East Asia. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 125, e2020JD032874 (2020).

Karnauskas, K. B., Lundquist, J. K. & Zhang, L. Southward shift of the global wind energy resource under high carbon dioxide emissions. Nat. Geosci. 11, 38–43 (2017).

Pryor, S. C., Barthelmie, R. J., Bukovsky, M. S., Leung, L. R. & Sakaguchi, K. Climate change impacts on wind power generation. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 1, 627–643 (2020).

Moemken, J., Reyers, M., Feldmann, H. & Pinto, J. G. Future changes of wind speed and wind energy potentials in EURO-CORDEX ensemble simulations. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 123, 6373–6389 (2018).

Gernaat, D. E. H. J. et al. Climate change impacts on renewable energy supply. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 119–125 (2021).

Lima, D. C. A. et al. The present and future offshore wind resource in the southwestern African region. Clim. Dyn. 56, 1371–1388 (2021).

Carvalho, D., Rocha, A., Costoya, X., deCastro, M. & Gómez-Gesteira, M. Wind energy resource over Europe under CMIP6 future climate projections: what changes from CMIP5 to CMIP6. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 151, 111594 (2021).

Barthelmie, R. J. & Pryor, S. C. Potential contribution of wind energy to climate change mitigation. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 684–688 (2014).

Hanna, R., Xu, Y. & Victor, D. G. After COVID-19, green investment must deliver jobs to get political traction. Nature 582, 178–180 (2020).

Liu, Z. et al. Challenges and opportunities for carbon neutrality in China. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 3, 141–155 (2022).

Zeng, N. et al. The Chinese carbon-neutral goal: challenges and prospects. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 39, 1229–1238 (2022).

Net-zero carbon pledges must be meaningful. Nature 592, 8 (2021).

Fiedler, S., Wyser, K., Rogelj, J. & van Noije, T. Radiative effects of reduced aerosol emissions during the COVID-19 pandemic and the future recovery. Atmos. Res. 264, 105866 (2021).

D’Souza, J. et al. Projected changes in seasonal and extreme summertime temperature and precipitation in India in response to COVID-19 recovery emissions scenarios. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 114025 (2021).

Lei, Y. D. et al. Avoided population exposure to extreme heat under two scenarios of global carbon neutrality by 2050 and 2060. Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 094041 (2022).

Lamboll, R. D. et al. Modifying emissions scenario projections to account for the effects of COVID-19: protocol for CovidMIP. Geosci. Model Dev. 14, 3683–3695 (2021).

Danso, D. K. et al. A CMIP6 assessment of the potential climate change impacts on solar photovoltaic energy and its atmospheric drivers in West Africa. Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 044016 (2022).

Hou, X., Wild, M., Folini, D., Kazadzis, S. & Wohland, J. Climate change impacts on solar power generation and its spatial variability in Europe based on CMIP6. Earth Syst. Dyn. 12, 1099–1113 (2021).

Wang, Z. L. et al. Evaluation of surface solar radiation trends over China since the 1960s in the CMIP6 models and potential impact of aerosol emissions. Atmos. Res. 268, 105991 (2022).

Schwarz, M., Folini, D., Yang, S., Allan, R. P. & Wild, M. Changes in atmospheric shortwave absorption as important driver of dimming and brightening. Nat. Geosci. 13, 110–115 (2020).

Salgueiro, V., Costa, M. J., Silva, A. M. & Bortoli, D. Effects of clouds on the surface shortwave radiation at a rural inland mid-latitude site. Atmos. Res. 178, 95–101 (2016).

Li, L. et al. A satellite-measured view of aerosol component content and optical property in a haze-polluted case over North China Plain. Atmos. Res. 266, 105958 (2022).

Chen, S. et al. Improved air quality in China can enhance solar-power performance and accelerate carbon-neutrality targets. One Earth 5, 550–562 (2022).

Jerez, S. et al. The impact of climate change on photovoltaic power generation in Europe. Nat. Commun. 6, 10014 (2015).

Lu, N. et al. High emission scenario substantially damages China’s photovoltaic potential. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL100068 (2022).

Akinsanola, A. A., Ogunjobi, K. O., Abolude, A. T. & Salack, S. Projected changes in wind speed and wind energy potential over West Africa in CMIP6 models. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 044033 (2021).

Net Zero by 2050: A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector (IEA, 2021).

Renewables 2022 (IEA, 2022).

Li, M. Q. et al. High-resolution data shows China’s wind and solar energy resources are enough to support a 2050 decarbonized electricity system. Appl. Energy 306, 117996 (2022).

Wang, Y. H. et al. Spatial and temporal variation of offshore wind power and its value along the Central California Coast. Environ. Res. Commun. 1, 121001 (2019).

He, Y. P., Monahan, A. H. & McFarlane, N. A. Diurnal variations of land surface wind speed probability distributions under clear-sky and low-cloud conditions. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 3308–3314 (2013).

Li, Y. et al. Climate model shows large-scale wind and solar farms in the Sahara increase rain and vegetation. Science 361, 1019–1022 (2018).

Zhou, L. M. et al. Impacts of wind farms on land surface temperature. Nat. Clim. Change 2, 539–543 (2012).

Walsh-Thomas, J. M., Cervone, G., Agouris, P. & Manca, G. Further evidence of impacts of large-scale wind farms on land surface temperature. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 16, 6432–6437 (2012).

Xu, S. Q. et al. Delayed use of bioenergy crops might threaten climate and food security. Nature 609, 299–306 (2022).

O’Neill, B. C. et al. The Scenario Model Intercomparison Project (ScenarioMIP) for CMIP6. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 3461–3482 (2016).

Fan, W. X. et al. Evaluation of global reanalysis land surface wind speed trends to support wind energy development using in situ observations. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 60, 33–50 (2021).

Urraca, R. et al. Evaluation of global horizontal irradiance estimates from ERA5 and COSMO-REA6 reanalyses using ground and satellite-based data. Sol. Energy 164, 339–354 (2018).

Xu, Z. F., Han, Y., Tam, C. Y., Yang, Z. L. & Fu, C. B. Bias-corrected CMIP6 global dataset for dynamical downscaling of the historical and future climate (1979-2100). Sci. Data 8, 293 (2021).

Wang, F. & Tian, D. On deep learning-based bias correction and downscaling of multiple climate models simulations. Clim. Dyn. 59, 3451–3468 (2022).

Cannon, A. J. Multivariate quantile mapping bias correction: an N-dimensional probability density function transform for climate model simulations of multiple variables. Clim. Dyn. 50, 31–49 (2018).

Cannon, A. J., Sobie, S. R. & Murdock, T. Q. Bias correction of GCM precipitation by quantile mapping: how well do methods preserve changes in quantiles and extremes? J. Clim. 28, 6938–6959 (2015).

Bichet, A. et al. Potential impact of climate change on solar resource in Africa for photovoltaic energy: analyses from CORDEX-AFRICA climate experiments. Environ. Res. Lett. 14, 124039 (2019).

TamizhMani, G., Ji, L., Tang, Y. & Petacci, L. Photovoltaic module thermal/wind performance: long-term monitoring and model development for energy rating. In NCPV and Solar Program Review Meeting Proceedings NREL/CP-520-35645 (National Renewable Energy Laboratory, 2003).

Chenni, R., Makhlouf, M., Kerbache, T. & Bouzid, A. A detailed modeling method for photovoltaic cells. Energy 32, 1724–1730 (2007).

Pryor, S. C. & Barthelmie, R. J. Assessing climate change impacts on the near-term stability of the wind energy resource over the United States. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 8167–8171 (2011).

Smith, O., Cattell, O., Farcot, E., O’Dea, R. D. & Hopcraft, K. I. The effect of renewable energy incorporation on power grid stability and resilience. Sci. Adv. 8, eabj6734 (2022).

Yan, Z. F., Hitt, J. L., Turner, J. A. & Mallouk, T. E. Renewable electricity storage using electrolysis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 12558–12563 (2020).

Zhang, B. C., Guo, Z., Zhang, L. X., Zhou, T. J. & Hayasaya, T. Cloud characteristics and radiation forcing in the global land monsoon region from multisource satellite data sets. Earth Space Sci. 7, e2019EA001027 (2020).

Li, J. D., Wang, W. C., Dong, X. Q. & Mao, J. Y. Cloud–radiation–precipitation associations over the Asian monsoon region: an observational analysis. Clim. Dyn. 49, 3237–3255 (2017).

Feng, H. H., Ye, S. C. & Zou, B. Contribution of vegetation change to the surface radiation budget: a satellite perspective. Glob. Planet. Change 192, 103225 (2020).

Martel, J. L. et al. CMIP5 and CMIP6 model projection comparison for hydrological impacts over North America. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL098364 (2022).

Dieng, D. et al. Multivariate bias-correction of high-resolution regional climate change simulations for West Africa: performance and climate change implications. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 127, e2021JD034836 (2022).

Singh, H., Najafi, M. R. & Cannon, A. J. Characterizing non-stationary compound extreme events in a changing climate based on large-ensemble climate simulations. Clim. Dyn. 56, 1389–1405 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We thank the CovidMIP project for providing simulation outputs. We also thank A. J. Cannon for sharing the MBCn package. This work was jointly supported by the Special Project of National Natural Science Foundation of China (42341202 to X.Z., Z.W. and H.C.), the National Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars (41825011 to H.C.) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42275042 to Z.W. and 42205118 to Y.L.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.L. and Z.W. conceived the study. Y.L., Z.W. and Y.X. performed the data analysis. Y.L. and Z.W. led the writing of this study, with discussion and improvement from Y.X. D.W., X.Z., H.C., X.Y., C.T., J.Z., L.G., L. Li, H.Z. and L. Liu provided valuable comments and contributed to constructive revisions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Climate Change thanks Michael Craig and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

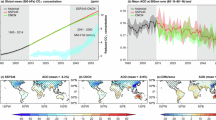

Extended Data Fig. 1 Changes of solar photovoltaic potential (\({{\boldsymbol{PV}}}_{{\boldsymbol{POT}}}\)) under different climate change scenarios, shown in absolute values rather than relative values in Fig.1.

(a), The changes of annual mean solar \({{PV}}_{{POT}}\) during 2040–2049 under SSP2-4.5 (S245) relative to the historical period (Unitless). (b)-(c), The changes of annual mean solar \({{PV}}_{{POT}}\) during 2040–2049 under the moderate (MOD) and strong (STR) carbon-neutral scenarios relative to S245 (Unitless). Hatched regions represent a change with high inter-model agreement defined as at least three of the four CovidMIP models agreeing on the direction of change.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Annual changes of temperature (T, units: °C) and downwelling shortwave radiation (I, units: W/m2).

(a-b), The changes of annual mean T and I during 2040–2049 under the SSP2-4.5 scenario (S245) relative to the historical period. (c-d), The changes of annual mean T and I during 2040–2049 under the moderate (MOD) carbon-neutral scenario relative to S245. (e-f), The changes of annual mean T and I during 2040–2049 under the strong (STR) carbon-neutral scenario relative to S245. Hatched regions represent a change with high inter-model agreement defined as at least three of the four CovidMIP models agreeing on the direction of change.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Changes of wind power (WP) under different climate change scenarios, shown in absolute values rather than relative values in Fig. 3.

(a), The changes of annual mean WP during 2040–2049 under SSP2-4.5 (S245) relative to the historical period (units: KW). (b)-(c), The changes of annual mean WP during 2040–2049 under the moderate (MOD) and strong (STR) carbon-neutral scenarios relative to S245 (units: KW). Hatched regions represent a change with high inter-model agreement defined as at least three of the four CovidMIP models agreeing on the direction of change.

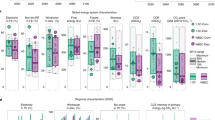

Extended Data Fig. 4 Changes of wind power density (WPD) (units: %).

(a), The relative changes of annual mean WPD during 2040–2049 under S245 relative to the historical period. (b)-(c), The relative changes of annual mean WPD during 2040–2049 under MOD and STR relative to S245. Hatched regions have changes with high inter-model agreement defined as at least three of the four models agreeing on the sign of changes. (d), Regional mean relative changes of annual WPD during 2040–2049 under the S245 (red bars), MOD (blue bars), and STR (green bars) scenarios relative to the historical period. The black error bars represent one standard deviation of four climate models. The hatched red (blue and green) bars have changes with high inter-model agreement during 2040–2049 under S245 (MOD and STR) relative to the historical period (S245).

Extended Data Fig. 5 Variability of solar photovoltaic potential (\({{\boldsymbol{PV}}}_{{\boldsymbol{POT}}}\)) and wind power (WP) at various time scales in the historical period.

(a), (c), and (e), Day-to-day, month-to-month, and year-to-year variability of solar \({{PV}}_{{POT}}\) in the historical period (units: %). (b), (d), and (f), same as left panels but for WP.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Spatial distributions of observed and simulated solar photovoltaic potential (\({{\boldsymbol{PV}}}_{{\boldsymbol{POT}}}\)) and Wind Power Density (WPD).

(a, b), Observed annual mean solar \({{PV}}_{{POT}}\) (Unitless) and WPD (units: W/m2) in the historical period (1995–2014). (c)-(d), The relative biases of solar \({{PV}}_{{POT}}\) and WPD from raw multi-model mean simulation (units: %). (e)-(f), The relative biases of solar \({{PV}}_{{POT}}\) and WPD from bias-corrected multi-model mean simulation (units: %). Please note the differences in color scales.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Estimate of annual mean wind speed in the historical period (1995-2014).

(a, b), Annual mean wind speed at 10 m and 100 m. (c), Annual mean of scaling factor \(\alpha\) converting 10 m wind speed to 100 m. Scaling factor was calculated from daily data before taking annual average.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Tables 1 and 2, and Supplementary Figs. 1–10.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Lei, Y., Wang, Z., Wang, D. et al. Co-benefits of carbon neutrality in enhancing and stabilizing solar and wind energy. Nat. Clim. Chang. 13, 693–700 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-023-01692-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-023-01692-7

This article is cited by

-

Behavioral uncertainty in EV charging drives heterogeneous grid load variability under climate goals

Nature Communications (2026)

-

Decreased Interhemispheric Asymmetries of Global Land Monsoon Precipitation toward the Carbon Neutrality Goal

Advances in Atmospheric Sciences (2026)

-

Detecting and calibrating large biases in global onshore wind power assessment across temporal scales

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Impacts of abatement in anthropogenic emissions in the context of China’s carbon neutrality on global photovoltaic potential

npj Climate and Atmospheric Science (2025)

-

Offshore wave and wind energy development in the Southern Hemisphere will remain optimal between 20°E and 180°E by 2100

Communications Earth & Environment (2025)