Abstract

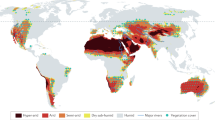

Compared with the risks associated with climate warming and extremes, the risks of climate-induced drying to animal species remain understudied. This is particularly true for water-sensitive groups, such as anurans (frogs and toads), whose long-term survival must be considered in the context of both environmental changes and species sensitivity. Here, we mapped global areas where anurans will face increasing water limitations, analysed ecotype sensitivity to water loss and modelled behavioural activity impacts under future climate change scenarios. Predictions indicate that 6.6–33.6% of anuran habitats will become arid like by 2080–2100, with 15.4–36.1% exposed to worsening drought, under an intermediate- and high-emission scenario, respectively. Arid conditions are expected to double water loss rates, and combined drought and warming will double reductions in anuran activity compared with warming impacts alone by 2080–2100. These findings underscore the pervasive synergistic threat of warming and environmental drying to anurans.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Climate data were sourced from a public database published in Abatzoglou et al.87 and Zhao and Dai2. The species richness database was sourced from the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species platform91 (https://www.iucnredlist.org/resources/spatial-data-download). Phylogenetic data were sourced from Jetz and Pyron97. Water loss and uptake data used to reproduce the study are available via GitHub at https://github.com/nicholaswunz/global-frog-drought and Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13743578 (ref. 113).

Code availability

Codes to reproduce the study are available via GitHub at https://github.com/nicholaswunz/global-frog-drought and Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13743578 (ref. 113).

References

Pokhrel, Y. et al. Global terrestrial water storage and drought severity under climate change. Nat. Clim. Chang. 11, 226–233 (2021).

Zhao, T. & Dai, A. CMIP6 model-projected hydroclimatic and drought changes and their causes in the twenty-first century. J. Clim. 35, 897–921 (2022).

Slette, I. J. et al. How ecologists define drought, and why we should do better. Glob. Chang. Biol. 25, 3193–3200 (2019).

Lowe, W. H., Martin, T. E., Skelly, D. K. & Woods, H. A. Metamorphosis in an era of increasing climate variability. Trends Ecol. Evol. 36, 360–375 (2021).

Zylstra, E. R., Swann, D. E., Hossack, B. R., Muths, E. & Steidl, R. J. Drought‐mediated extinction of an arid‐land amphibian: insights from a spatially explicit dynamic occupancy model. Ecol. Appl. 29, e01859 (2019).

Lillywhite, H. B. Water relations of tetrapod integument. J. Exp. Biol. 209, 202–226 (2006).

Hillman, S. S., Withers, P. C., Drewes, R. C. & Hillyard, S. D. Ecological and Environmental Physiology of Amphibians Vol. 1 (Oxford Univ. Press, 2009).

Li, Y., Cohen, J. M. & Rohr, J. R. Review and synthesis of the effects of climate change on amphibians. Integr. Zool. 8, 145–161 (2013).

Campbell Grant, E. H., Miller, D. A. & Muths, E. A synthesis of evidence of drivers of amphibian declines. Herpetologica 76, 101–107 (2020).

Snyder, G. K. & Weathers, W. W. Temperature adaptations in amphibians. Am. Nat. 109, 93–101 (1975).

Gunderson, A. R. & Stillman, J. H. Plasticity in thermal tolerance has limited potential to buffer ectotherms from global warming. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 282, 20150401 (2015).

Pottier, P. et al. Vulnerability of amphibians to global warming. Preprint at EcoEvoRxiv https://doi.org/10.32942/X2T02T (2024).

Murali, G., Iwamura, T., Meiri, S. & Roll, U. Future temperature extremes threaten land vertebrates. Nature 615, 461–467 (2023).

Luedtke, J. A. et al. Ongoing declines for the world’s amphibians in the face of emerging threats. Nature 622, 308–314 (2023).

Williams, S. E., Shoo, L. P., Isaac, J. L., Hoffmann, A. A. & Langham, G. Towards an integrated framework for assessing the vulnerability of species to climate change. PLoS Biol. 6, e325 (2008).

Rozen‐Rechels, D. et al. When water interacts with temperature: ecological and evolutionary implications of thermo‐hydroregulation in terrestrial ectotherms. Ecol. Evol. 9, 10029–10043 (2019).

Trenberth, K. E. et al. Global warming and changes in drought. Nat. Clim. Chang. 4, 17–22 (2014).

Park Williams, A. et al. Temperature as a potent driver of regional forest drought stress and tree mortality. Nat. Clim. Chang. 3, 292–297 (2013).

Grossiord, C. et al. Plant responses to rising vapor pressure deficit. New Phytol. 226, 1550–1566 (2020).

Eamus, D., Boulain, N., Cleverly, J. & Breshears, D. D. Global change‐type drought‐induced tree mortality: vapor pressure deficit is more important than temperature per se in causing decline in tree health. Ecol. Evol. 3, 2711–2729 (2013).

Kearney, M. R., Munns, S. L., Moore, D., Malishev, M. & Bull, C. M. Field tests of a general ectotherm niche model show how water can limit lizard activity and distribution. Ecol. Monogr. 88, 672–693 (2018).

Lertzman‐Lepofsky, G. F., Kissel, A. M., Sinervo, B. & Palen, W. J. Water loss and temperature interact to compound amphibian vulnerability to climate change. Glob. Chang. Biol. 26, 4868–4879 (2020).

Anderson, R. C. & Andrade, D. V. Trading heat and hops for water: dehydration effects on locomotor performance, thermal limits and thermoregulatory behavior of a terrestrial toad. Ecol. Evol. 7, 9066–9075 (2017).

Galindo, C., Cruz, E. & Bernal, M. Evaluation of the combined temperature and relative humidity preferences of the Colombian terrestrial salamander Bolitoglossa ramosi (Amphibia: Plethodontidae). Can. J. Zool. 96, 1230–1235 (2018).

Navas, C. A., Antoniazzi, M. M., Carvalho, J. E., Suzuki, H. & Jared, C. Physiological basis for diurnal activity in dispersing juvenile Bufo granulosus in the Caatinga, a Brazilian semi-arid environment. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 147, 647–657 (2007).

Toledo, R. & Jared, C. Cutaneous adaptations to water balance in amphibians. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Physiol. 105, 593–608 (1993).

Carvalho, J. E., Navas, C. A. & Pereira, I. C. in Aestivation: Molecular and Physiological Aspects (eds Navas, C. A. & Carvalho, J. E.) 141–169 (Springer, 2010).

Withers, P. C. Cocoon formation and structure in the estivating Australian desert frogs, Neobatrachus and Cyclorana. Aust. J. Zool. 43, 429–441 (1995).

Tracy, C. R., Reynolds, S. J., McArthur, L., Tracy, C. R. & Christian, K. A. Ecology of aestivation in a cocoon-forming frog, Cyclorana australis (Hylidae). Copeia 2007, 901–912 (2007).

Amey, A. P. & Grigg, G. C. Lipid-reduced evaporative water loss in two arboreal hylid frogs. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Physiol. 111, 283–291 (1995).

Stinner, J. N. & Shoemaker, V. H. Cutaneous gas exchange and low evaporative water loss in the frogs Phyllomedusa sauvagei and Chiromantis xerampelina. J. Comp. Physiol. B 157, 423–427 (1987).

Shoemaker, V. H. & McClanahan, L. L. Nitrogen excretion and water balance in amphibians of Borneo. Copeia 3, 446–451 (1980).

Pough, F. H., Taigen, T. L., Stewart, M. M. & Brussard, P. F. Behavioral modification of evaporative water loss by a Puerto Rican frog. Ecology 64, 244–252 (1983).

Sodhi, N. S. et al. Measuring the meltdown: drivers of global amphibian extinction and decline. PLoS ONE 3, e1636 (2008).

Ficetola, G. F. & Maiorano, L. Contrasting effects of temperature and precipitation change on amphibian phenology, abundance and performance. Oecologia 181, 683–693 (2016).

Wassens, S., Walcott, A., Wilson, A. & Freire, R. Frog breeding in rain-fed wetlands after a period of severe drought: implications for predicting the impacts of climate change. Hydrobiologia 708, 69–80 (2013).

Kohli, A. K. et al. Disease and the drying pond: examining possible links among drought, immune function and disease development in amphibians. Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 92, 339–348 (2019).

Kupferberg, S. J. et al. Seasonal drought and its effects on frog population dynamics and amphibian disease in intermittent streams. Ecohydrology 15, e2395 (2022).

Thorson, T. B. The relationship of water economy to terrestrialism in amphibians. Ecology 36, 100–116 (1955).

Katz, U. & Graham, R. Water relations in the toad (Bufo viridis) and a comparison with the frog (Rana ridibunda). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Physiol. 67, 245–251 (1980).

Withers, P. C., Hillman, S. S. & Drewes, R. C. Evaporative water loss and skin lipids of anuran amphibians. J. Exp. Zool. 232, 11–17 (1984).

Wygoda, M. L. Low cutaneous evaporative water loss in arboreal frogs. Physiol. Zool. 57, 329–337 (1984).

de Andrade, D. V. & Abe, A. S. Evaporative water loss and oxygen uptake in two casque-headed tree frogs, Aparasphenodon brunoi and Corythomantis greeningi (Anura, Hylidae). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Physiol. 118, 685–689 (1997).

Schwarzkopf, L. & Alford, R. Desiccation and shelter-site use in a tropical amphibian: comparing toads with physical models. Funct. Ecol. 10, 193–200 (1996).

Seebacher, F. & Alford, R. A. Shelter microhabitats determine body temperature and dehydration rates of a terrestrial amphibian (Bufo marinus). J. Herpetol. 36, 69–75 (2002).

IPCC Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis, Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2021).

Malhi, Y. et al. Climate Change, deforestation and the fate of the Amazon. Science 319, 169–172 (2008).

Phillips, O. L. et al. Drought sensitivity of the Amazon rainforest. Science 323, 1344–1347 (2009).

Mitchell, A. & Bergmann, P. J. Thermal and moisture habitat preferences do not maximize jumping performance in frogs. Funct. Ecol. 30, 733–742 (2016).

Guevara-Molina, E. C., Gomes, F. R. & Camacho, A. Effects of dehydration on thermoregulatory behavior and thermal tolerance limits of Rana catesbeiana (Shaw, 1802). J. Therm. Biol. 93, 102721 (2020).

Preest, M. & Pough, F. H. Interaction of temperature and hydration on locomotion of toads. Funct. Ecol. 3, 693–699 (1989).

Walvoord, M. E. Cricket frogs maintain body hydration and temperature near levels allowing maximum jump performance. Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 76, 825–835 (2003).

Feder, M. E. & Burggren, W. W. Environmental Physiology of the Amphibians (Univ. of Chicago Press, 1992).

Wu, N. C. & Seebacher, F. Physiology can predict animal activity, exploration and dispersal. Commun. Biol. 5, 109 (2022).

Hillman, S. S. Dehydrational effects on cardiovascular and metabolic capacity in two amphibians. Physiol. Zool. 60, 608–613 (1987).

Hillman, S. S. The roles of oxygen delivery and electrolyte levels in the dehydrational death of Xenopus laevis. J. Comp. Physiol. 128, 169–175 (1978).

Hillman, S. S. Dehydrational effects on brain and cerebrospinal fluid electrolytes in two amphibians. Physiol. Zool. 61, 254–259 (1988).

Gatten, R. E. Jr. Activity metabolism of anuran amphibians: tolerance to dehydration. Physiol. Zool. 60, 576–585 (1987).

Qiu, R. et al. Soil moisture dominates the variation of gross primary productivity during hot drought in drylands. Sci. Total Environ. 899, 165686 (2023).

Janzen, D. H. & Schoener, T. W. Differences in insect abundance and diversity between wetter and drier sites during a tropical dry season. Ecology 49, 96–110 (1968).

Tracy, C. R. et al. Thermal and hydric implications of diurnal activity by a small tropical frog during the dry season. Austral Ecol. 38, 476–483 (2013).

Forti, L. R., Hepp, F., de Souza, J. M., Protazio, A. & Szabo, J. K. Climate drives anuran breeding phenology in a continental perspective as revealed by citizen‐collected data. Divers. Distrib. 28, 2094–2109 (2022).

Walpole, A. A., Bowman, J., Tozer, D. C. & Badzinski, D. S. Community-level response to climate change: shifts in anuran calling phenology. Herpetol. Conserv. Biol. 7, 249–257 (2012).

Miller, D. A. et al. Quantifying climate sensitivity and climate-driven change in North American amphibian communities. Nat. Commun. 9, 3926 (2018).

Díaz-Paniagua, C. et al. Groundwater decline has negatively affected the well-preserved amphibian community of Doñana National Park (SW Spain). Amphib. Reptil. 45, 1–13 (2024).

Seebacher, F., White, C. R. & Franklin, C. E. Physiological plasticity increases resilience of ectothermic animals to climate change. Nat. Clim. Chang. 5, 61–66 (2015).

Wygoda, M. Adaptive control of water loss resistance in an arboreal frog. Herpetologica 44, 251–257 (1988).

Riddell, E. A., Roback, E. Y., Wells, C. E., Zamudio, K. R. & Sears, M. W. Thermal cues drive plasticity of desiccation resistance in montane salamanders with implications for climate change. Nat. Commun. 10, 4091 (2019).

Chown, S. L., Sørensen, J. G. & Terblanche, J. S. Water loss in insects: an environmental change perspective. J. Insect Physiol. 57, 1070–1084 (2011).

Hoffmann, A., Hallas, R., Dean, J. & Schiffer, M. Low potential for climatic stress adaptation in a rainforest Drosophila species. Science 301, 100–102 (2003).

Sheridan, J. A., Mendenhall, C. D. & Yambun, P. Frog body size responses to precipitation shift from resource‐driven to desiccation‐resistant as temperatures warm. Ecol. Evol. 12, e9589 (2022).

Guo, C., Gao, S., Krzton, A. & Zhang, L. Geographic body size variation of a tropical anuran: effects of water deficit and precipitation seasonality on Asian common toad from southern Asia. BMC Evol. Biol. 19, 208 (2019).

Castro, K. M. et al. Water constraints drive allometric patterns in the body shape of tree frogs. Sci. Rep. 11, 1218 (2021).

Gouveia, S. F. et al. Biophysical modeling of water economy can explain geographic gradient of body size in anurans. Am. Nat. 193, 51–58 (2019).

Daufresne, M., Lengfellner, K. & Sommer, U. Global warming benefits the small in aquatic ecosystems. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 12788–12793 (2009).

Gardner, J. L., Peters, A., Kearney, M. R., Joseph, L. & Heinsohn, R. Declining body size: a third universal response to warming? Trends Ecol. Evol. 26, 285–291 (2011).

Sheridan, J. A. & Bickford, D. Shrinking body size as an ecological response to climate change. Nat. Clim. Chang. 1, 401–406 (2011).

Wu, N. C. & Seebacher, F. Bisphenols alter thermal responses and performance in zebrafish (Danio rerio). Conserv. Physiol. 9, coaa138 (2021).

Kellermann, V., McEvey, S. F., Sgrò, C. M. & Hoffmann, A. A. Phenotypic plasticity for desiccation resistance, climate change and future species distributions: will plasticity have much impact? Am. Nat. 196, 306–315 (2020).

Gerick, A. A., Munshaw, R. G., Palen, W. J., Combes, S. A. & O’Regan, S. M. Thermal physiology and species distribution models reveal climate vulnerability of temperate amphibians. J. Biogeogr. 41, 713–723 (2014).

Wu, Y. et al. Hydrological projections under CMIP5 and CMIP6: sources and magnitudes of uncertainty. Bull. Am. Meterorol. Soc. 105, E59–E74 (2024).

Li, H. et al. Drylands face potential threat of robust drought in the CMIP6 SSPs scenarios. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 114004 (2021).

Ukkola, A. M., De Kauwe, M. G., Roderick, M. L., Abramowitz, G. & Pitman, A. J. Robust future changes in meteorological drought in CMIP6 projections despite uncertainty in precipitation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL087820 (2020).

Spinoni, J. et al. Future global meteorological drought hot spots: a study based on CORDEX data. J. Clim. 33, 3635–3661 (2020).

Dai, A., Trenberth, K. E. & Qian, T. A global dataset of Palmer Drought Severity Index for 1870–2002: relationship with soil moisture and effects of surface warming. J. Hydrometeorol. 5, 1117–1130 (2004).

Budyko, M. I. The heat balance of the earth’s surface. Sov. Geogr. 2, 3–13 (1961).

Abatzoglou, J. T., Dobrowski, S. Z., Parks, S. A. & Hegewisch, K. C. TerraClimate, a high-resolution global dataset of monthly climate and climatic water balance from 1958–2015. Sci. Data 5, 170191 (2018).

Eyring, V. et al. Overview of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) experimental design and organization. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 1937–1958 (2016).

Cook, B. I. et al. Megadroughts in the common era and the Anthropocene. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 3, 741–757 (2022).

Qing, Y. et al. Accelerated soil drying linked to increasing evaporative demand in wet regions. NPJ Clim. Atmos. Sci. 6, 205 (2023).

The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Version 2022-2 https://www.iucnredlist.org/ (2022).

Moen, D. S. & Wiens, J. J. Microhabitat and climatic niche change explain patterns of diversification among frog families. Am. Nat. 190, 29–44 (2017).

O’Dea, R. E. et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses in ecology and evolutionary biology: a PRISMA extension. Biol. Rev. 96, 1695–1722 (2021).

Senzano, L. M. & Andrade, D. V. Temperature and dehydration effects on metabolism, water uptake and the partitioning between respiratory and cutaneous evaporative water loss in a terrestrial toad. J. Exp. Biol. 221, jeb188482 (2018).

Pick, J. L., Nakagawa, S. & Noble, D. W. Reproducible, flexible and high‐throughput data extraction from primary literature: the metaDigitise R package. Methods Ecol. Evol. 10, 426–431 (2019).

Schwanz, L. E. et al. Best practices for building and curating databases for comparative analyses. J. Exp. Biol. 225, jeb243295 (2022).

Jetz, W. & Pyron, R. A. The interplay of past diversification and evolutionary isolation with present imperilment across the amphibian tree of life. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2, 850–858 (2018).

Paradis, E. & Schliep, K. ape 5.0: An environment for modern phylogenetics and evolutionary analyses in R. Bioinformatics 35, 526–528 (2018).

Hoffman, M. D. & Gelman, A. The No-U-Turn sampler: adaptively setting path lengths in Hamiltonian Monte Carlo. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 15, 1593–1623 (2014).

Bürkner, P.-C. brms: An R package for Bayesian multilevel models using Stan. J. Stat. Softw. 80, 1–28 (2017).

Gelman, A. & Rubin, D. B. Inference from iterative simulation using multiple sequences. Stat. Sci. 7, 457–472 (1992).

Riddell, E. A., Apanovitch, E. K., Odom, J. P. & Sears, M. W. Physical calculations of resistance to water loss improve predictions of species range models. Ecol. Monogr. 87, 21–33 (2017).

Pottier, P. et al. New horizons for comparative studies and meta-analyses. Trends Ecol. Evol. 39, 435–445 (2024).

Nakagawa, S., Noble, D. W., Senior, A. M. & Lagisz, M. Meta-evaluation of meta-analysis: ten appraisal questions for biologists. BMC Biol. 15, 18 (2017).

Lüdecke, D., Ben-Shachar, M. S., Patil, I., Waggoner, P. & Makowski, D. performance: An R package for assessment, comparison and testing of statistical models. J. Open Source Softw. 6, 3139 (2021).

Kearney, M. R. & Porter, W. P. NicheMapR—an R package for biophysical modelling: the ectotherm and dynamic energy budget models. Ecography 43, 85–96 (2020).

Kearney, M. R. & Enriquez‐Urzelai, U. A general framework for jointly modelling thermal and hydric constraints on developing eggs. Methods Ecol. Evol. 14, 583–595 (2023).

Greenberg, D. A. & Palen, W. J. Hydrothermal physiology and climate vulnerability in amphibians. Proc. Biol. Sci. 288, 20202273 (2021).

Beuchat, C. A., Pough, F. H. & Stewart, M. M. Response to simultaneous dehydration and thermal stress in three species of Puerto Rican frogs. J. Comp. Physiol. B 154, 579–585 (1984).

Titon, B. Jr, Navas, C. A., Jim, J. & Gomes, F. R. Water balance and locomotor performance in three species of neotropical toads that differ in geographical distribution. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 156, 129–135 (2010).

Bartelt, P. E. A Biophysical Analysis of Habitat Selection in Western Toads (Bufo boreas) in Southeastern Idaho. PhD thesis, Idaho State Univ. (2000).

Christian, J. I. et al. Global projections of flash drought show increased risk in a warming climate. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 165 (2023).

Wu, N. C. et al. Global exposure risk of frogs to increasing environmental dryness (dataset). https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13743578 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This paper is dedicated to the late Phillip J. Bishop (1957–2021), who was at the forefront of amphibian conservation research in the southern hemisphere. He dedicated more than 30 years to amphibian conservation, and this study was inspired partly by his research and his passion for amphibians demonstrated at the Word Congress of Herpetology in Dunedin, New Zealand, in 2020. This work was supported by the Institute of Vertebrate Biology of the Czech Academy of Sciences (no. RVO: 68081766) to U.E.U., the São Paulo Research Foundation—FAPESP (nos. 10/20061-6, 14/05624-5, 17/10338-0 and 19/04637-0 to R.P.B. and 14/16320-7 to C.A.N.) and the National Research Foundation of South Africa (incentive funding no. 28442 to S.C.-T).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.C.W. and C.A.N. conceived the study. N.C.W. and J.D.K. compiled the data. R.P.B., C.A.N. and S.C.-T. provided additional data for 39 species. M.R.K. and U.E.U. developed the model simulations. N.C.W. analysed the data, produced the figures and wrote the initial draft. All authors contributed to revisions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Climate Change thanks David Miller, Susan Walls and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

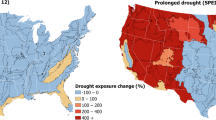

Extended Data Fig. 1 Risk to increasing drought intensity for anurans by 2080–2100.

(a) Change in the Palmer Drought Severity Index (ΔPDSI) under a + 2 °C warming scenario (Shared Socioeconomic Pathways 2–4.5; SPP2–4.5) by 2080–2100 relative to the current scenario (1970–1999). A decrease ΔPDSI indicates higher drought occurrences, while an increase ΔPDSI indicates more extreme wetness. (b) Percentage of anuran species occupancy in each PDSI category grid cell (0.5°) under a + 2 °C warming scenario, where 21% of species are in areas that are at risk of increasing drought. (c) Change in ΔPDSI under a + 4 °C warming scenario (SPP5–8.5). (d) Percentage of anuran species occupancy in each PDSI category grid cell (0.5°) under a + 4 °C warming scenario, where 38% of species are in areas that are at risk of increasing drought.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Risk to increasing drought frequency for anurans by 2080–2100.

(a) Change in the drought frequency (ΔPDSI[frequency]) under a + 2 °C warming scenario (Shared Socioeconomic Pathways 2–4.5; SPP2–4.5) by 2080–2100 relative to the current scenario (1970–1999). ΔPDSI[frequency] was defined as change in monthly PDSI below −2 (moderate to extreme drought) within a 20 year period. (b) Percentage of anuran species occupancy in each frequency category grid cell (0.5°) under a + 2 °C warming scenario. (c) Change in the ΔPDSI[frequency] under a + 4 °C warming scenario (SPP5–8.5). (d) Percentage of anuran species occupancy in each frequency category grid cell (0.5°) under a + 4 °C warming scenario.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Risk to increasing drought duration for anurans by 2080–2100.

(a) Change in the drought duration (ΔPDSI[duration]) under a + 2 °C warming scenario (Shared Socioeconomic Pathways 2–4.5; SPP2–4.5) by 2080–2100 relative to the current scenario (1970–1999). ΔPDSI[duration] was defined as consecutive months under moderate to extreme drought (PDSI < −2) within a 20 year period. (b) Percentage of anuran species occupancy in each duration category grid cell (0.5°) under a + 2 °C warming scenario. (c) Change in the ΔPDSI[duration] under a + 4 °C warming scenario (SPP5–8.5). (d) Percentage of anuran species occupancy in each duration category grid cell (0.5°) under a + 4 °C warming scenario.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–13, methods and Tables 1–7.

Supplementary Code

Web page supplementary information with code used to reproduce the study.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, N.C., Bovo, R.P., Enriquez-Urzelai, U. et al. Global exposure risk of frogs to increasing environmental dryness. Nat. Clim. Chang. 14, 1314–1322 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-024-02167-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-024-02167-z

This article is cited by

-

Vulnerability of amphibians to global warming

Nature (2025)