Abstract

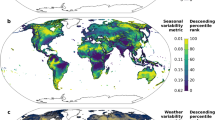

Prolonged low-wind events, termed wind droughts, threaten wind turbine electricity generation, yet their future trajectories remain poorly understood. Here, using hourly data from 21 IPCC models, we reveal robust increasing trends in wind drought duration at both global and regional scales by 2100, across low- and high-CO2 scenarios. These trends are primarily driven by declining mid-latitude cyclone frequencies and Arctic warming. Notably, the duration of 25-year return events is projected to increase by up to 20% under low warming scenarios and 40% under very high warming scenarios in northern mid-latitude countries, threatening energy security in these densely populated areas. Additionally, record-breaking wind drought extremes will probably become more frequent in a warming climate, particularly in eastern North America, western Russia, northeastern China and north-central Africa. Our analysis suggests that ~20% of existing wind turbines are in regions at high future risk of record-breaking wind drought extremes, a factor not yet considered in current assessments.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All the data used in this study are available online via the following links. The data for quantifying wind drought changes are available via the ERA5 at https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.adbb2d47 (ref. 66) and the MERRA2 at https://doi.org/10.5067/VJAFPLI1CSIV (ref. 67). Projected wind drought changes in CMIP6 are available at the Program for Climate Model Diagnosis and Intercomparison (https://aims2.llnl.gov/search). The land-cover map was obtained from the MCD12C1 (https://doi.org/10.5067/MODIS/MCD12C1.006) and the Ecoregions 2017 (https://ecoregions.appspot.com). The terrain elevation is from GTOPO30 at https://doi.org/10.5066/F7DF6PQS. Global wind power density was derived from the Global Wind Atlas (https://globalwindatlas.info/en/download/gis-files). The global dataset of wind farm locations and power are available via Figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.11310269.v2 (ref. 85). All data generated in this study are available via the Peking University Open Research Data Platform at https://doi.org/10.18170/DVN/50VDAL (ref. 86).

Code availability

All codes used in this study are available via the Peking University Open Research Data Platform at https://doi.org/10.18170/DVN/50VDAL (ref. 86).

References

Antonini, E. G. A. et al. Identification of reliable locations for wind power generation through a global analysis of wind droughts. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 103 (2024).

ECHO. 31 January 2014: Eastern–Central Europe—Severe Weather. Reliefweb https://reliefweb.int/map/romania/31-january-2014-eastern-central-europe-severe-weather (2014).

Robbins, J. Gone with the winds? What happens if there is a ‘global terrestrial stilling’. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists https://thebulletin.org/2022/09/gone-with-the-winds-what-happens-if-there-is-a-global-terrestrial-stilling/ (2022).

Ram, R. S. What is behind the curious decline in generation of renewable energy. mint www.livemint.com/market/mark-to-market/what-is-behind-the-curious-decline-in-generation-of-renewable-energy-11569864546939.html (2019).

Staffell, I., Green, R., Green, T. & Jansen, M. Q1 (2021). Electric Insights Quarterly Reports https://reports.electricinsights.co.uk/reports/q1-2021/ (2021)

Pechlivanidis, I. et al. Benchmarking Skill Assessment of Current Sub-Seasonal and Seasonal Forecast Systems for Users’ Selected Case Studies (S2S4E, 2019); https://s2s4e.eu/sites/default/files/2020-06/s2s4e_d41.pdf

Truyts, J. & Vandervelden, J. België telde negen dagen ‘Dunkelflaute’ in januari. vrtnws.be www.vrt.be/vrtnws/nl/2017/02/24/belgie_telde_negendagendunkelflauteinjanuari-1-2900900/ (2017).

Li, B., Basu, S., Watson, S. J. & Russchenberg, H. W. J. A brief climatology of Dunkelflaute events over and surrounding the North and Baltic Sea areas. Energies 14, 6508 (2021).

Wetzel, D. Die, Dunkelflaute‘ bringt Deutschlands Stromversorgung ans Limit. WELT www.welt.de/wirtschaft/article161831272/Die-Dunkelflaute-bringt-Deutschlands-Stromversorgung-ans-Limit.html (2017).

Li, B., Basu, S., Watson, S. J. & Russchenberg, H. W. J. Quantifying the predictability of a ‘Dunkelflaute’ event by utilizing a mesoscale model. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 1618, 062042 (2020).

Bloomfield, H. What Europe’s exceptionally low winds mean for the future energy grid. The Conversation http://theconversation.com/what-europes-exceptionally-low-winds-mean-for-the-future-energy-grid-170135 (2021).

Rife, D., Krakauer, N., Cohan, D. & Collier, C. A new kind of drought: U.S. record low windiness in 2015. Earthzine https://earthzine.org/a-new-kind-of-drought-u-s-record-low-windiness-in-2015/ (2016).

Lledó, L., Bellprat, O., Doblas-Reyes, F. J. & Soret, A. Investigating the effects of Pacific sea surface temperatures on the wind drought of 2015 over the United States. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 123, 4837–4849 (2018).

Hingtgen, J., Le, D., Davis, B. & Huang, B. Productivity and Status of Wind Generation in California (California Energy Commission, 2019). https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.35900.90244

The February 2021 Cold Weather Outages in Texas and the South Central United States (FERC, 2021); www.ferc.gov/media/february-2021-cold-weather-outages-texas-and-south-central-united-states-ferc-nerc-and

Liu, F., Wang, X., Sun, F. & Wang, H. Wind resource droughts in China. Environ. Res. Lett. 18, 094015 (2023).

Ohba, M., Kanno, Y. & Bando, S. Effects of meteorological and climatological factors on extremely high residual load and possible future changes. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 175, 113188 (2023).

Ohba, M., Kanno, Y. & Nohara, D. Climatology of dark doldrums in Japan. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 155, 111927 (2022).

Shekhar, J., Saji, S., Agarwal, D., Ahmed, A. & Joseph, T. Assessing and Planning for Variability in India’s Wind Resource (CEEW, 2021); www.ceew.in/publications/studying-the-impact-of-unexpected-climate-change-on-wind-energy-sector-in-india

Dawkins, L. C. Weather and Climate Related Sensitivities and Risks in a Highly Renewable UK Energy System: A Literature Review (Met Office, 2019).

Zheng, D. et al. Climate change impacts on the extreme power shortage events of wind–solar supply systems worldwide during 1980–2022. Nat. Commun. 15, 5225 (2024).

Future of Wind: Deployment, Investment, Technology, Grid Integration and Socio-Economic Aspects (International Renewable Energy Agency, 2019).

Martinez, A. & Iglesias, G. Global wind energy resources decline under climate change. Energy 288, 129765 (2024).

Pryor, S. C., Barthelmie, R. J., Bukovsky, M. S., Leung, L. R. & Sakaguchi, K. Climate change impacts on wind power generation. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 1, 627–643 (2020).

Pryor, S. C., Barthelmie, R. J. & Kjellström, E. Potential climate change impact on wind energy resources in northern Europe: analyses using a regional climate model. Clim. Dynam. 25, 815–835 (2005).

Reyers, M., Moemken, J. & Pinto, J. G. Future changes of wind energy potentials over Europe in a large CMIP5 multi-model ensemble. Int. J. Climatol. 36, 783–796 (2016).

Hueging, H., Haas, R., Born, K., Jacob, D. & Pinto, J. G. Regional changes in wind energy potential over Europe using regional climate model ensemble projections. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 52, 903–917 (2013).

Tobin, I. et al. Assessing climate change impacts on European wind energy from ENSEMBLES high-resolution climate projections. Clim. Change 128, 99–112 (2015).

Pryor, S. C., Barthelmie, R. J. & Schoof, J. T. Past and future wind climates over the contiguous USA based on the North American Regional Climate Change Assessment Program model suite. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. https://doi.org/10.1029/2012JD017449 (2012).

Greene, J. S., Chatelain, M., Morrissey, M. & Stadler, S. Projected future wind speed and wind power density trends over the western US High Plains. Atmos. Clim. Sci. 02, 32–40 (2012).

Pryor, S. C., Shepherd, T. J., Bukovsky, M. & Barthelmie, R. J. Assessing the stability of wind resource and operating conditions. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 1452, 012084 (2020).

Karnauskas, K. B., Lundquist, J. K. & Zhang, L. Southward shift of the global wind energy resource under high carbon dioxide emissions. Nat. Geosci. 11, 38–43 (2018).

IPCC. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis (eds Masson-Delmotte, V. et al.) (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2021).

Zha, J. et al. Projected changes in global terrestrial near-surface wind speed in 1.5 °C–4.0 °C global warming levels. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 114016 (2021).

Deng, K., Azorin-Molina, C., Minola, L., Zhang, G. & Chen, D. Global near-surface wind speed changes over the last decades revealed by reanalyses and CMIP6 model simulations. J. Clim. 34, 2219–2234 (2021).

Russo, M. A., Carvalho, D., Martins, N. & Monteiro, A. Future perspectives for wind and solar electricity production under high-resolution climate change scenarios. J. Clean. Prod. 404, 136997 (2023).

Claro, A., Santos, J. A. & Carvalho, D. Assessing the future wind energy potential in Portugal using a CMIP6 model ensemble and WRF high-resolution simulations. Energies 16, 661 (2023).

Carvalho, D., Rocha, A., Costoya, X., deCastro, M. & Gómez-Gesteira, M. Wind energy resource over Europe under CMIP6 future climate projections: what changes from CMIP5 to CMIP6. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 151, 111594 (2021).

deCastro, M. et al. An overview of offshore wind energy resources in Europe under present and future climate. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1436, 70–97 (2019).

Haupt, S. E. et al. A method to assess the wind and solar resource and to quantify interannual variability over the United States under current and projected future climate. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 55, 345–363 (2016).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Gelaro, R. et al. The modern-era retrospective analysis for research and applications, version 2 (MERRA-2). J. Clim. 30, 5419–5454 (2017).

Eyring, V. et al. Overview of the coupled model intercomparison project phase 6 (CMIP6) experimental design and organization. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 1937–1958 (2016).

O’Neill, B. C. et al. The scenario model intercomparison project (ScenarioMIP) for CMIP6. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 3461–3482 (2016).

Brown, P. T., Farnham, D. J. & Caldeira, K. Meteorology and climatology of historical weekly wind and solar power resource droughts over western North America in ERA5. SN Appl. Sci. 3, 814 (2021).

Davis, N. N. et al. The global wind atlas: a high-resolution dataset of climatologies and associated web-based application. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 104, E1507–E1525 (2023).

Seltzer, A. M., Blard, P.-H., Sherwood, S. C. & Kageyama, M. Terrestrial amplification of past, present, and future climate change. Sci. Adv. 9, eadf8119 (2023).

Rudeva, I., Gulev, S. K., Simmonds, I. & Tilinina, N. The sensitivity of characteristics of cyclone activity to identification procedures in tracking algorithms. Tellus A 66, 24961 (2014).

McCabe, G. J., Clark, M. P. & Serreze, M. C. Trends in Northern Hemisphere surface cyclone frequency and intensity. J. Clim. 14, 2763–2768 (2001).

Chang, E. K. M., Ma, C., Zheng, C. & Yau, A. M. W. Observed and projected decrease in Northern Hemisphere extratropical cyclone activity in summer and its impacts on maximum temperature. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 2200–2208 (2016).

Gentile, E. S., Zhao, M. & Hodges, K. Poleward intensification of midlatitude extreme winds under warmer climate. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 6, 219 (2023).

Tamarin-Brodsky, T. & Kaspi, Y. Enhanced poleward propagation of storms under climate change. Nat. Geosci. 10, 908–913 (2017).

Seo, K.-H. et al. What controls the interannual variation of Hadley cell extent in the Northern Hemisphere: physical mechanism and empirical model for edge variation. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 6, 204 (2023).

Shaw, T. A. et al. Storm track processes and the opposing influences of climate change. Nat. Geosci. 9, 656–664 (2016).

Thompson, V. et al. The most at-risk regions in the world for high-impact heatwaves. Nat. Commun. 14, 2152 (2023).

Fischer, E. M., Sippel, S. & Knutti, R. Increasing probability of record-shattering climate extremes. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 689–695 (2021).

Dunnett, S., Sorichetta, A., Taylor, G. & Eigenbrod, F. Harmonised global datasets of wind and solar farm locations and power. Sci. Data 7, 130 (2020).

Pryor, S. C., Nikulin, G. & Jones, C. Influence of spatial resolution on regional climate model derived wind climates. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 117, 2011JD016822 (2012).

Gutowski, W. J. Jr. et al. WCRP COordinated Regional Downscaling EXperiment (CORDEX): a diagnostic MIP for CMIP6. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 4087–4095 (2016).

Lake, I., Gutowski, W., Giorgi, F. & Lee, B. CORDEX: climate research and information for regions. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 98, ES189–ES192 (2017).

Chen, X. et al. Pathway toward carbon-neutral electrical systems in China by mid-century with negative CO2 abatement costs informed by high-resolution modeling. Joule 5, 2715–2741 (2021).

Richardson, D., Pitman, A. J. & Ridder, N. N. Climate influence on compound solar and wind droughts in Australia. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 6, 184 (2023).

Gernaat, D. E. H. J. et al. Climate change impacts on renewable energy supply. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 119–125 (2021).

Chen, W.-H. & Hsieh, I.-Y. L. Techno-economic analysis of lithium-ion battery price reduction considering carbon footprint based on life cycle assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 425, 139045 (2023).

Staffell, I. et al. The role of hydrogen and fuel cells in the global energy system. Energy Environ. Sci. 12, 463–491 (2019).

ERA5: Fifth Generation of ECMWF Atmospheric Reanalyses of the Global Climate (Copernicus Climate Data Store, accessed 8 May 2023); https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.adbb2d47

MERRA-2 tavg1_2d_slv_Nx: 2d,1-Hourly, Time-Averaged, Single-Level, Assimilation,Single-Level Diagnostics V5.12.4 (GES DISC, accessed 28 October 2022); https://doi.org/10.5067/VJAFPLI1CSIV

Jourdier, B. Evaluation of ERA5, MERRA-2, COSMO-REA6, NEWA and AROME to simulate wind power production over France. Adv. Sci. Res. 17, 63–77 (2020).

Olauson, J. ERA5: The new champion of wind power modelling? Renew. Energy 126, 322–331 (2018).

General Electric GE 2.5-120. Wind-turbine-models.com https://en.wind-turbine-models.com/turbines/310-ge-vernova-ge-2.5-120 (2018).

Gao, M. et al. Secular decrease of wind power potential in India associated with warming in the Indian Ocean. Sci. Adv. 4, eaat5256 (2018).

Archer, C. L. & Jacobson, M. Z. Evaluation of global wind power. J. Geophys. Res. 110, D12110 (2005).

Walton, R. A., Takle, E. S. & Gallus, W. A. Characteristics of 50–200-m winds and temperatures derived from an Iowa tall-tower network. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 53, 2387–2393 (2014).

Friedl, M. & Sulla-Menashe, D. MCD12C1 MODIS/Terra+Aqua Land Cover Type Yearly L3 Global 0.05Deg CMG V006 (NASA Land Processes Distributed Active Archive Center, accessed 20 January 2023); https://doi.org/10.5067/MODIS/MCD12C1.006

Greene, C. A., Blankenship, D. D., Gwyther, D. E., Silvano, A. & van Wijk, E. Wind causes Totten Ice Shelf melt and acceleration. Sci. Adv. 3, e1701681 (2017).

Cushing, L. J., Li, S., Steiger, B. B. & Casey, J. A. Historical red-lining is associated with fossil fuel power plant siting and present-day inequalities in air pollutant emissions. Nat. Energy 8, 52–61 (2023).

Deng, K. et al. The offshore wind speed changes in China: an insight into CMIP6 model simulation and future projections. Clim. Dynam. 62, 3305–3319 (2024).

Pryor, S. C. & Barthelmie, R. J. A global assessment of extreme wind speeds for wind energy applications. Nat. Energy 6, 268–276 (2021).

Zeng, Z. et al. A reversal in global terrestrial stilling and its implications for wind energy production. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 979–985 (2019).

Eyring, V. et al. Reflections and projections on a decade of climate science. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 279–285 (2021).

Tong, Y. et al. Bias correction of temperature and precipitation over China for RCM simulations using the QM and QDM methods. Clim. Dynam. 57, 1425–1443 (2021).

Potisomporn, P., Adcock, T. A. A. & Vogel, C. R. Extreme value analysis of wind droughts in Great Britain. Renew. Energy 221, 119847 (2024).

Coles, S. An Introduction to Statistical Modeling of Extreme Values (Springer, 2001).

Shiau, J. T. Return period of bivariate distributed extreme hydrological events. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 17, 42–57 (2003).

Dunnett, S. Harmonised global datasets of wind and solar farm locations and power. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.11310269.v2 (2020).

Meng, Q. Prolonged wind droughts in a warming climate threaten global wind power security. Peking University Open Research Data Platform https://doi.org/10.18170/DVN/50VDAL (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42275194) and National Key Research and Development Programme of China (2023YFC3707404).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.S. designed the experiments and M.Q. carried them out. Z.Z. and B.Y. contributed to the data analysis. H.Z., X.Y. and X.L. contributed to the result interpretation. M.Q. and L.S. prepared the paper with contributions from all co-authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Climate Change thanks David Carvalho, Sue Ellen Haupt and Eugene Takle for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Notes 1–5, Figs. 1–19 and Tables 1–5.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Qu, M., Shen, L., Zeng, Z. et al. Prolonged wind droughts in a warming climate threaten global wind power security. Nat. Clim. Chang. 15, 842–849 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-025-02387-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-025-02387-x

This article is cited by

-

‘Wind droughts’ driven by climate change put green power at risk

Nature (2025)

-

Wind droughts threaten energy reliability

Nature Climate Change (2025)