Abstract

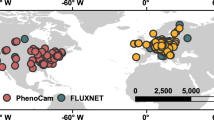

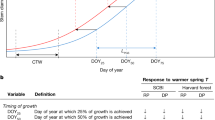

The dynamics of carbon allocation in trees affect carbon storage of forest ecosystems and atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations on Earth. Here, using carbon fluxes and xylem phenology from 84 conifer forests across the Northern Hemisphere, we quantify the phenology of carbon sources (photosynthesis) and sinks (stem growth) along a thermal gradient from −4.4 to 18.2 °C in mean annual temperature. The onset of stem growth advances by 2.3 days per degree Celsius with rising temperatures, 2 times slower than photosynthesis. Warmer sites accumulate less chilling than colder sites, thus trees require more heat to reactivate. The ending of photosynthesis and wood formation is delayed by 2.0 days per degree Celsius. Overall, the photosynthetic season lengthens by one month more than the growing season towards the warmest sites. Climate warming tends to intensify the mismatch between the phenology of carbon sources and sinks, potentially affecting the carbon sequestration in conifer forests.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Data generated in this study are available from https://doi.org/10.11888/Terre.tpdc.301513 (ref. 65). Wood formation raw data can be accessed using the procedure in Borealis: https://doi.org/10.5683/SP3/JRDOU1 (ref. 66). FluxSat data can be accessed from https://doi.org/10.3334/ORNLDAAC/1835 (ref. 67). Climate data can be accessed from https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.6c68c9bb (ref. 68). Details of all study sites are listed in Supplementary Material. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Code generated in this study is available from https://doi.org/10.11888/Terre.tpdc.301513 (ref. 65).

References

Pan, Y. et al. The enduring world forest carbon sink. Nature 631, 563–569 (2024).

Litton, C. M., Raich, J. W. & Ryan, M. G. Carbon allocation in forest ecosystems. Glob. Change Biol. 13, 2089–2109 (2007).

Rossi, S. et al. Pattern of xylem phenology in conifers of cold ecosystems at the northern hemisphere. Glob. Change Biol. 22, 3804–3813 (2016).

Friend, A. D. et al. On the need to consider wood formation processes in global vegetation models and a suggested approach. Ann. For. Sci. 76, 49 (2019).

Cabon, A. et al. Cross-biome synthesis of source versus sink limits to tree growth. Science 376, 758–761 (2022).

Rocha, A. V. et al. On linking interannual tree ring variability with observations of whole-forest CO2 flux. Glob. Change Biol. 12, 1378–1389 (2006).

Pappas, C. et al. Aboveground tree growth is a minor and decoupled fraction of boreal forest carbon input. Agric. For. Meteorol. 290, 108030 (2020).

Krejza, J. et al. Disentangling carbon uptake and allocation in the stems of a spruce forest. Environ. Exp. Bot. 196, 104787 (2022).

Silvestro, R. et al. Partial asynchrony of coniferous forest carbon sources and sinks at the intra-annual time scale. Nat. Commun. 15, 6169 (2024).

Keenan, T. F. et al. Net carbon uptake has increased through warming-induced changes in temperate forest phenology. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 598–604 (2014).

Dow, C. et al. Warm springs alter timing but not total growth of temperate deciduous trees. Nature 608, 552–557 (2022).

Li, X. et al. Warming-induced phenological mismatch between trees and shrubs explains high-elevation forest expansion. Nat. Sci. Rev. 10, nwad182 (2023).

Silvestro, R. et al. A longer wood growing season does not lead to higher carbon sequestration. Sci. Rep. 13, 4059 (2023).

Zhang, J. et al. Drought limits wood production of Juniperus przewalskii even as growing seasons lengthens in a cold and arid environment. Catena 196, 104936 (2021).

Gao, S. et al. An earlier start of the thermal growing season enhances tree growth in cold humid areas but not in dry areas. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 6, 397–404 (2022).

Yang, Q. et al. Two dominant boreal conifers use contrasting mechanisms to reactivate photosynthesis in the spring. Nat. Commun. 11, 128 (2020).

Ensminger, I., Busch, F. & Huner, N. P. A. Photostasis and cold acclimation: sensing low temperature through photosynthesis. Physiol. Plant. 126, 28–44 (2006).

Körner, C. Paradigm shift in plant growth control. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 25, 107–114 (2015).

Lin et al. Spring wood phenology responds more strongly to chilling temperatures than bud phenology in European conifers. Tree Physiol. 44, tpad146 (2024).

Asse, D. et al. Warmer winters reduce the advance of tree spring phenology induced by warmer springs in the Alps. Agric. For. Meteorol. 252, 220–230 (2018).

Fu, Y. H. et al. Declining global warming effects on the phenology of spring leaf unfolding. Nature 526, 104–107 (2015).

Vitasse, Y., Signarbieux, C. & Fu, Y. H. Global warming leads to more uniform spring phenology across elevations. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 1004–1008 (2018).

Zani et al. Increased growing-season productivity drives earlier autumn leaf senescence in temperate trees. Science 370, 1066–1071 (2020).

Yang, B. et al. New perspective on spring vegetation phenology and global climate change based on Tibetan Plateau tree-ring data. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 6966–6971 (2017).

Zhang, Y. et al. Light limitation regulates the response of autumn terrestrial carbon uptake to warming. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 739–743 (2020).

Mu, W. et al. Photoperiod drives cessation of wood formation in northern conifers. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 32, 603–617 (2023).

Joiner, J. et al. Estimation of terrestrial global gross primary production (GPP) with satellite data-driven models and eddy covariance flux data. Remote Sens. 10, 1346 (2018).

Bond, B. et al. Foliage physiology and biochemistry in response to light gradients in conifers with varying shade tolerance. Oecologia 120, 183–192 (1999).

Sage, R. F. & Kubien, D. S. The temperature response of C3 and C4 photosynthesis. Plant Cell Environ. 30, 1086–1106 (2007).

Oquist, G. & Huner, N. P. Photosynthesis of overwintering evergreen plants. Ann. Rev. Plant Biol. 54, 329–355 (2003).

Gričar, J. et al. Effect of local heating and cooling on cambial activity and cell differentiation in the stem of Norway spruce (Picea abies). Ann. Bot. 97, 943–951 (2006).

Bauerle, W. L. et al. Photoperiodic regulation of the seasonal pattern of photosynthetic capacity and the implications for carbon cycling. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 8612–8617 (2012).

Huang, J. et al. Photoperiod and temperature as dominant environmental drivers triggering secondary growth resumption in northern hemisphere conifers. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 20645–20652 (2020).

Fréchette, E., Chang, C. Y.-Y. & Ensminger, I. Variation in the phenology of photosynthesis among eastern white pine provenances in response to warming. Glob. Change Biol. 26, 5217–5234 (2020).

Körner, C. Carbon limitation in trees. J. Ecol. 91, 4–17 (2003).

Froux, F. et al. Seasonal variations and acclimation potential of the thermostability of photochemistry in four Mediterranean conifers. Ann. For. Sci. 61, 235–241 (2004).

Ensminger, I. et al. Intermittent low temperatures constrain spring recovery of photosynthesis in boreal Scots pine forests. Glob. Change Biol. 10, 995–1008 (2004).

Yang, Y. et al. Effects of winter chilling vs. spring forcing on the spring phenology of trees in a cold region and a warmer reference region. Sci. Total Environ. 725, 138323 (2020).

Cartenì, F. et al. PhenoCaB: a new phenological model based on carbon balance in boreal conifers. N. Phytol. 239, 592–605 (2023).

Way, D. A. & Sage, R. F. Elevated growth temperatures reduce the carbon gain of black spruce [Picea mariana (Mill.) BSP]. Glob. Change Biol. 14, 624–636 (2008).

Dusenge, M. E., Duarte, A. G. & Way, D. A. Plant carbon metabolism and climate change: elevated CO2 and temperature impacts on photosynthesis, photorespiration and respiration. New Phytol. 221, 32–49 (2019).

Niu, S. et al. Temperature responses of ecosystem respiration. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 5, 55–571 (2024).

Liu, H. et al. Phenological mismatches between above- and belowground plant responses to climate warming. Nat. Clim. Change 12, 97–102 (2022).

Way, D. A. & Oren, R. Differential responses to changes in growth temperature between trees from different functional groups and biomes: a review and synthesis of data. Tree Physiol. 30, 669–688 (2010).

Camarero, J. J. et al. Decoupled leaf-wood phenology in two pine species from contrasting climates: longer growing seasons do not mean more radial growth. Agr. For. Meteorol. 327, 109223 (2022).

Camarero, J. J., Olano, J. M. & Parras, A. Plastic bimodal xylogenesis in conifers from continental Mediterranean climates. N. Phytol. 185, 471–480 (2010).

Papadopoulos, A. Tree-ring patterns and climate response of Mediterranean fir populations in central Greece. Dendrochronologia 40, 17–25 (2016).

Niinemets, Ü. & Keenan, T. Photosynthetic responses to stress in Mediterranean evergreens: mechanisms and models. Environ. Exp. Bot. 103, 24–41 (2014).

D’Andrea, E. et al. Unravelling resilience mechanisms in forests: role of non-structural carbohydrates in responding to extreme weather events. Tree Physiol. 41, 1808–1818 (2021).

Rossi, S., Anfodillo, T. & Menardi, R. Trephor: a new tool for sampling microcores from tree stems. IAWA J. 27, 89–97 (2006).

Lv, Y. et al. How well do light-use efficiency models capture large-scale drought impacts on vegetation productivity compared with data-driven estimates? Ecol. Indic. 146, 109739 (2023).

Wang, X. et al. No trends in spring and autumn phenology during the global warming hiatus. Nat. Commun. 10, 2389 (2019).

Camarero, J. J., Guerrero-Campo, J. & Gutiérrez, E. Tree-ring growth and structure of Pinus uncinata and Pinus sylvestris in the Central Spanish Pyrenees. Arct. Alp. Res. 30, 1–10 (1998).

Boogaard, H. & van der Grijn, G. Product user guide and specification data stream 2: AgERA5 historic and near real-time forcing data global agriculture. Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS) https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/user-guide (2019).

Warton, D. I. et al. SMATR 3—an R package for estimation and inference about allometric lines. Methods Ecol. Evol. 3, 257–259 (2012).

Bronaugh, D., Werner, A. & Bronaugh, M.D. zyp: Zhang + Yue-Pilon trends package. R version 0.11-1 https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/zyp/index.html (2023).

Thornthwaite, C. W. An approach toward a rational classification of climate. Geogr. Rev. 38, 55–94 (1948).

Begueria, S. & Vicente-Serrano, S. M. SPEI: Calculation of the standardised precipitation-evapotranspiration index. R version 1.8.1 https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/SPEI/index.html (2023).

Liaw, A. & Winener, M. Classification and regression by randomforest. R News https://journal.r-project.org/articles/RN-2002-022/RN-2002-022.pdf (2022).

Lenth, R. V. emmeans: Estimated marginal means, aka least squares means. R version 1.5.3 https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/emmeans/index.html (2020).

Hervé, M. RVAideMemoire: Testing and plotting procedures for biostatistics. R version 0.9–75 https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/RVAideMemoire/index.html (2020).

Bürkner, P. C. brms: an R package for Bayesian multilevel models using Stan. J. Stat. Softw. 80, 1–28 (2017).

Sakai, A. Studies of frost hardiness in woody plants. II. Effect of temperature on hardening. Plant Physiol. 41, 353–359 (1966).

R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2020); https://www.R-project.org/

Li, X. et al. Data from: warming increases the pehnological mismatch between carbon sources and sinks in conifers. National Tibetal Plateau/Third Pole Environment Data Center https://doi.org/10.11888/Terre.tpdc.301513 (2025).

Silvestro, R. et al. Replication data for: partial asynchrony of coniferous forest carbon sources and sinks at the intra-annual time scale. Borealis V1 https://doi.org/10.5683/SP3/JRDOU1 (2024).

Joiner, J. & Yoshida, Y. Global MODIS and FLUXNET-derived daily gross primary production, V2. ORNL DAAC https://doi.org/10.3334/ORNLDAAC/1835 (2021).

Boogaard, H. et al. Agrometeorological indicators from 1979 to present derived from reanalysis, version 2.0. Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS) https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.6c68c9bb (2020).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2024YFF0809101), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42271065, 42361144710, 42361144856), the Sino-German Center for Research Promotion Project (M-0393), the Youth Innovation Promotion Association Program of Chinese Academy of Sciences (2020073), the Chinese Academy of Sciences President’s International Fellowship Initiative (2025PD0108) and the State Scholarship Fund (202004910219) provided by the China Scholarship Council. This research is also a product of the FAIRWOOD project funded by the Centre for the Synthesis and Analysis of Biodiversity (CESAB) of the French Foundation for Research on Biodiversity (FRB). Other funding agencies included the Ministère des Forêts, de la Faune et des Parcs du Québec (Quebec, Canada, project number 112332139 conducted at the Direction de la recherche forestière and led by J.D.S. and G.D.), Fonds de Recherche du Québec–Nature et Technologies (AccFor, project number 309064), the Observatoire régional de recherche en forêt boréale and Forêt d’Enseignement et de Recherche Simoncouche and Université Laval’s Forêt Montmorency. R. Silvestro received the Merit scholarship for international PhD students (PBEEE) by the Fonds de Recherche du Québec–Nature et Technologies (FRQNT) and a scholarship for an internship by the Centre d’étude de la forêt (CEF) realized at the Centre for Ecological Research and Forestry Applications (CREAF). F.B. was funded, in part, by the Experiment Station of the College of Agriculture, Biotechnology and Natural Resources at the University of Nevada, Reno. V.S. appreciated the support of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation (project number FSRZ-2023-0007). C.B.K.R. acknowledges support from ‘Laboratoire d’Excellence’ ARBRE (Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR), Investissements d’Avenir, ANR-11-LABX-0002-01) and the SILVATECH facility (https://doi.org/10.15454/1.5572400113627854E12) for its contribution to the acquisition of wood formation data. K.Č., J.G. and P.P. were funded by the Slovenian Research and Innovation Agency (ARIS), research core funding numbers P4-0430 and P4-0015, projects J4-2541, J4-4541 and Z4-7318, while K.Č., V.G., P.P. and H.V. were also funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme ASFORCLIC under the grant agreement 36 number 952314. V.T. was supported by the Johannes Amos Comenius Programme (P JAC), project number CZ.02.01.01/00/22_008/0004605, Natural and Anthropogenic Georisks. A. Giovannelli received funding from National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), Mission 4 Component 2 Investment 1.4-Call for tender number 3138 of 16 December 2021, rectified by decree number 3175 of 18 December 2021 of the Italian Ministry of University and Research funded by the European Union–NextGeneration EU; project code CN_00000033, concession decree number 1034 of 17 June 2022 adopted by the Italian Ministry of University and Research, Unique Project Code (CUP) B83C22002930006, project title ‘National Biodiversity Future Center—NBFC’. A. Gruber was funded by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) (grant number https://doi.org/10.55776/P34706). P.F. was funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation through projects ‘INtra-seasonal Tree growth along Elevational GRAdients in the European ALps (INTEGRAL)’ (grant number 121859), ‘Coupling stem water flow and structural carbon allocation in a warming climate: the Lötschental study case (LOTFOR)’ (grant number 150205), and ‘Calibrating Earth Observation-based impacts of drought on mountain forests by monitoring Carbon fixation and transpiration: from individual tree responses to regional scale extrapolation (CALEIDOSCOPE)’ (grant number 212902).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.L., R. Silvestro, M.M., E.L. and S.R. conceived the ideas and designed methodology; M.M., J.J.C., C.B.K.R., J.D.S., C.N., A. Giovannelli, A.S., L.S., R.G., J.G., P.P., R.L.P., K.Č., B.Y., S.A., E.B., F.B., F.C., M.C., M.D.L., A.D., G.D., M.F., M.V.F., P.F., A. Gruber, V.G., A. Güney, J.K., A.V.K., A.A.K., F.L., H.M., R.A.M., E.M.d.C., P.N., W.O., A.P.O., V.S., R. Sukumar, R.T., V.T., H.V., J.V., Q.Z. and E.Z. provided local wood formation data. R.G.-V. downloaded and assembled FluxSat data; X.L. and S.R. assembled the final datasets; X.L., J.D.S., M.M. and R. Silvestro analysed data; X.L. led the writing of the paper. All authors contributed to the drafts and gave final approval for publication.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Climate Change thanks Daniel Metcalfe and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Variance partitioning of phenological events among biome, species and site levels.

Results were estimated from type I ANOVA (n = 121). Abbreviations: Ph_onset, onset of photosynthesis; EL_onset, onset of cell enlargement; WT_onset, onset of wall thickening; M_onset, onset of cell maturity; EL_end, end of cell enlargement; XL_end, end of wall thickening; Ph_end, end of photosynthesis.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Permutation importance of climatic factors on the onset, end and duration of wood formation and photosynthesis.

Random forest models were used to quantify and compare the effects of climate variables on the phenological events. Model performances including the root mean squared error (RMSE) and the R2 for both the training and test set have been shown in Supplementary Table 1. Temperature, precipitation, AI represent mean annual temperature, mean total annual precipitation, mean annual aridity index, and mean annual shortwave downward radiation, respectively.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Variation in timing gaps between photosynthesis and wood formation according to mean annual temperatures.

Individual points represent species×site observations, n = 121. The r and P values indicate the correlation between onset or end gaps and mean annual temperatures of the study sites. All the relationships are significant, with P values less than 0.05.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Relationships between wood production and maximum growth rate in the Mediterranean biome.

Individual points represent species×site observations, n = 19. The r and P values indicate the correlation between wood production and maximum growth rate in this biome. The relationship is significant with P values less than 0.05.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Relationships between wood production and photosynthetic and wood growing season lengths across four biomes.

Individual points represent species×site observations, n = 121. The r and P values indicate the correlation between wood production and photosynthetic and wood growing season lengths across four biomes. The relationships are significant with P values less than 0.05.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Methods, Tables 1–11, Figs. 1–13 and References.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 5

Statistical source data.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, X., Silvestro, R., Liang, E. et al. Warming increases the phenological mismatch between carbon sources and sinks in conifers. Nat. Clim. Chang. 15, 1363–1370 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-025-02474-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-025-02474-z