Abstract

Decisions about natural resource management are frequently complex and vexed, often leading to public policy compromises. Discord between environmental and economic metrics creates problems in assessing trade-offs between different current or potential resource uses. Ecosystem accounts, which quantify ecosystems and their benefits for human well-being consistent with national economic accounts, provide exciting opportunities to contribute significantly to the policy process. We advanced the application of ecosystem accounts in a regional case study by explicitly and spatially linking impacts of human and natural activities on ecosystem assets and services to their associated industries. This demonstrated contributions of ecosystems beyond the traditional national accounts. Our results revealed that native forests would provide greater benefits from their ecosystem services of carbon sequestration, water yield, habitat provisioning and recreational amenity if harvesting for timber production ceased, thus allowing forests to continue growing to older ages.

Similar content being viewed by others

Ecosystem accounting has the potential to contribute to the policy process by re-framing debates about natural resource management1,2. Accounts help circumvent polarized arguments about the relative importance of environmental versus economic factors by systematically and regularly assessing the costs and benefits of changing ecosystem assets and services. Accounting involves quantification, both spatially and temporally, in physical terms that can be linked to monetary values. By incorporating a range of ecosystem services in the accounts, the analysis becomes broader than the often two opposing viewpoints. Such an approach may facilitate a convergence of opinion about the need for change—by demonstrating explicit comparisons between land uses—and a process for change by quantifying physical and monetary metrics3. Finding solutions to conflicting land uses becomes a process of maximizing benefits for the public good, and not just economic growth and private gain. Hence, ecosystem accounts may be critical for setting agendas for natural resource management at many levels: regional land use conflicts, national policies such as State of the Environment report recommendations and international agreements such as the Sustainable Development Goals4.

The System of Environmental Economic Accounting (SEEA)5 is an internationally agreed statistical standard for combining environmental and economic information in a form appropriate for policy-makers. This system provides a standard model for the policy process in which the production boundary of the economy lies within the environment. Accounts are a system of organizing information in which the measurement of environmental–economic relationships can be described in physical or monetary terms. Ecosystem accounting6 includes contributions of ecosystems to the environmental–economic system, which are linked explicitly to economic activity and human well-being. Ecosystem accounts synthesize data on all assets, goods and services—those accounted for within the economic system and, in particular, the System of National Accounts (SNA), which produces the aggregate gross domestic product (GDP)7, and those that lie outside this system as unrecognized contributions of ecosystems to economic activity and human well-being3. A model of the environmental–economic system (Fig. 1) shows the stocks and flows of natural resources and the stages at which quantification in physical and/or monetary terms can be applied to make comparisons.

Ecosystem assets are identified and their physical state measured in a spatially explicit manner in terms of extent and condition, their ownership and management (individuals, industries or government). Thus, ecosystems are linked directly to uses by people. The uses of these ecosystem assets by human activities are the ecosystem services. Ecosystem services are combined with human inputs, such as capital and labour, in the production of goods and services, which produce benefits when used by people. Different sectors of society are the beneficiaries of these products. The production of goods and services can impact other ecosystem assets and these trade-offs can be assessed. Components of the system are quantified using physical or monetary metrics. Only parts of the system (indicated by the dashed line) are included in the calculation of GDP, which accounts for flows of market goods and services, such as agricultural products, timber products, water supply, tourism and recreational services. Non-market goods and services that are not accounted for in the GDP include clean air, protection from flooding and soil erosion, biodiversity, aesthetic benefits and climate change mitigation. The boundary of contributions of ecosystem services to markets or non-markets is difficult to define (that is, the position of the dashed line). Activities are assessed at balance points where components of the system are reasonably comparable: the use of ecosystem services can be complementary or conflicting; trade-offs resulting from the relative impacts or benefits of producing goods and services; and who benefits within human society. NGOs, non-government organizations.

Ecosystem accounting provides information for decision-making about trade-offs between the economy and the environment and activities within the economy, as well as evaluating trends over time and management options8. Indeed, ecosystem accounts have shown that gains in environmental benefits can be achieved alongside economic growth9. However, demonstrating the utility of accounting for specific decisions has been difficult10,11,12, and is probably best tackled at the scale of a region in which decisions are made. The technical nature of accounting is often poorly understood by policy-makers and their reluctance to engage with accounting may result from the difficult choices revealed10. Ecosystem services constitute one component of the SEEA; they have been ascribed financial values13,14 and applied to comparisons of multiple land uses15, but it has been similarly difficult to demonstrate their direct application to decision-making11.

Here, we present a key advance in ecosystem accounting by linking spatially quantified ecosystem assets and services with their contributions to industries, in a form consistent with the SNA7, as well as identifying the contributions of ecosystem services not included in the SNA. Such ecosystem accounts have broad applications for informing land use and meso-scale economic management decisions because many sources, types and scales of information are integrated. Information includes collections of economic units, such as businesses to industries, capital within and outside the SNA, biophysical characteristics and processes across the landscape, and relationships between ecosystems and the services they provide for human benefits. The accounts are comprehensive in terms of the economic activities, ecosystem assets and services, and their spatial context within the landscape, which are relevant to the land management decisions for the region. Integration of data across scales to present information at the regional or meso-scale is key for government decisions about land use change, as distinct from information relevant to local business decisions or national accounts. The accounting approach uses exchange values, which distinguishes it from other estimates of the value of ecosystem services16,17. Estimating exchange values for ecosystem services means that the contribution of these services can be seen in the national accounts, compared with the current situation in which they are hidden or ignored.

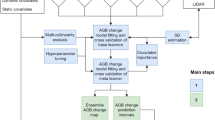

Our accounts were derived from detailed site and remotely sensed biophysical data and ecosystem-specific functions, together with economic data obtained from existing national, sub-national and business accounts. The accounts are presented at spatial and temporal scales relevant to land management decisions—activities undertaken within a region over years to decades. We advanced the application of the SEEA accounting framework by assessing the contributions of ecosystems at three levels of the environmental–economic interaction relevant to management issues: (1) ecosystem services, both currently measured and previously unrecognized in the national accounts; (2) economic uses of ecosystem services by industries as their contribution to GDP, as measured by an industry value added (IVA) metric (the sum of all IVAs equals GDP); and (3) gains and losses in IVA and ecosystem services involved with trade-offs between land uses. The key outcome was the capacity to quantify ecosystem services and their contribution to industries, and hence explicitly reveal the trade-offs required when the uses of services by different industries conflict. The accounting framework facilitates comparisons of values, but does not necessitate payment for the services.

We demonstrate the advantages of using the ecosystem accounting approach, based on the above three levels of environmental–economic interaction, to inform decision-making in a case study region: the tall, wet forests of the Central Highlands of Victoria, Australia (see Methods). Ecosystem accounting provided a valuable method for informing land management policy about complex issues and within the timeframe for decision-making. The accounts were applied spatially at the regional scale and were inclusive of the main activities and services in the region, rather than studies of polarized activities and their specific services, or restricted to the goods and services currently in the SNA and used in economic analysis.

Issues of native forest management in the Central Highlands are common to many regions globally where productive uses of ecosystem assets conflict with conservation objectives. Ecosystem services occurring within the region were identified and located spatially (Fig. 2). Monetary valuations were assessed for the following: provisioning services of water as well as timber from native forest and plantations; regulating services used in the production of crops, fodder and livestock; cultural and recreational services; and regulating services of carbon sequestration. Additionally, the habitat provisioning services for biodiversity were assessed using physical metrics (see Methods). Selection of the ecosystem services was based on the ecosystems occurring within the region, characteristics of their ecosystem services, and the decision-making context18. Classification of the ecosystem services used the international standard from the Common International Classification of Ecosystem Services19 with the addition of habitat provisioning services.

Results

The accounts revealed that the greatest values of ecosystem service were derived from provisioning for water and regulating services used in agricultural production and for carbon sequestration, with the lowest values from native forest and plantation timber provisioning (Fig. 3a). The contribution to GDP of the associated industries showed even greater differences between industries, with the economic value of agricultural production, water supply and tourism an order of magnitude above that of native forestry (Fig. 3b).

a, The monetary value of ecosystem services when used by industries or households is expressed as changes over time that reflect the changes in stocks and price. Water provisioning was the most valuable ecosystem service from the study area, but since 2014, the regulating ecosystem services used in agricultural production have been greater. The trend in carbon sequestration reflects only changes in net carbon stocks because a constant carbon price, adjusted for inflation, was applied. Decreases in carbon sequestration occurred after fires in 2007 and 2009 due to emissions from combustion, but then increased in the following years. b, Contributions of industries to the economy, based on the metric of IVA, show that agriculture, water supply and tourism are an order of magnitude above that of native forestry. IVA for plantation forestry is greater than that for native forestry, even though the area of land managed for plantations is 14% of the area of native forest available for harvest. The decrease in IVA for water supply from 2012 to 2013 was due to the expenses associated with constructing a desalination plant. Revenue increased in the following two years due to a higher price for water. The IVA for tourism has increased since 2012, mainly due to increased numbers of international visitors, aided by the declining exchange rate since the global financial crisis and mining boom.

Trade-offs are required when the same resource may be used for more than one purpose, especially if uses are mutually incompatible, or the use of one resource affects the condition of other assets or the same type of asset in different areas. An example in our case study relates to the impact of native forest timber harvesting on reducing forest age, which decreases the ecosystem condition of the forest for water yield and carbon storage, as well as biodiversity and recreational services. Trade-offs in physical and monetary terms of ecosystem services and IVA were derived from analyses of the counterfactual case; the difference in services if harvesting had not occurred (Table 1 and Fig. 4). This analysis allowed a comparison of the losses from ceasing native forest timber harvesting with the gains in carbon sequestration, water yield and habitat provisioning if forest growth continued, leading to greater forest age. Data were available for these ecosystem services to assess the differences between harvested regrowth forest and old growth forest.

Trade-offs in values of ecosystem services and IVA were derived from analyses of the counterfactual case (that is, the difference in values of services if harvesting had not occurred). This analysis allows comparison of the losses from ceasing native forest timber harvesting with the gains in other ecosystem services if forest growth continued leading to greater forest age. Gains in carbon sequestration and water yield were quantified and considered as known gains. Gains in cultural and recreational services and plantation timber provisioning were estimated from information in the literature, with a low and high range, and considered as potential gains.

Gains in water yield occur if forests continue growing without harvesting, because young, regenerating forests have higher rates of evapotranspiration than older forests. The reduction in water yield in regenerating forest was up to 29% in harvested regrowth from 1939 and up to 48% in harvested old growth forest (Supplementary Fig. 1). In the area that had been logged, the reduction in water yield was estimated to be an average of 10.5 GL yr−1, equivalent to AUD$2.5 million yr−1. This water yield would be gained if the forests were allowed to continue growing rather than being harvested.

The carbon sequestration potential of ceasing native forest timber harvesting and allowing continued forest growth was estimated to be 3 tC ha−1 yr−1 (averaged between 1990 and 2015), which is equivalent to AUD$134 ha−1 yr−1. Over the area of forest that had been logged, this potential increase in carbon stock was 0.344 MtC yr−1, equivalent AUD$15.5 million yr−1 (Table 1).

Gains occur in habitat provisioning services for biodiversity through the improved ecosystem condition of older forests. Old growth forests had an average number of hollow-bearing trees (HBTs) of 12.1 ha−1 with similar rates of losses and gains of trees. Regrowth forests after logging had an average of 3.6 HBTs ha−1 with a nearly five-fold greater rate of loss of trees than gain over the 28 year monitoring period. The potential gain would be 8.5 HBTs ha−1 if harvesting ceased and the forests were allowed to continue growing to an old growth state (Table 1). Metrics of biodiversity and habitat provisioning services indicated an overall decline in the state and condition of populations and their habitats. Species accounts showed an increase in the number of threatened species and severity of their threat classes. Numbers of arboreal marsupials declined, along with the number of HBTs on which they depended. The key threatening process for these animals was the accelerated loss of HBTs in younger forests and the impaired recruitment of new trees due to native forest harvesting20.

Accounting for carbon sequestration and water yield alone revealed that there would have been a small net loss in the value of ecosystem services (–AUD$0.7 million yr−1) if harvesting had not occurred. The trade-offs in carbon and water were quantified (see Methods) and considered as known gains (Fig. 4a). However, ecosystem services used for culture and recreation, as well as agricultural and plantation timber production, which currently account for about half the total value of ecosystem services, would also very likely increase and more than account for the difference. Trade-offs in cultural and recreational services and plantation timber provisioning were estimated and considered as potential gains, with a low and high range in their values (Fig. 4a). Estimated values of ecosystem services were based on information about the potential expansion of tourism if a larger area of native forest was protected21 and substitution of wood products by plantations. Native forest timber harvesting does not directly affect agricultural production because they occur on different areas of land.

The trade-off in habitat provisioning services is a known gain that was quantified (Table 1), but not valued in monetary terms. Economic valuation of habitat provisioning and biodiversity is problematic and was not attempted in this study, although it has been done previously using welfare values22. The species within the study area clearly had value, as evidenced by the efforts made to conserve many of them (for example, their being listing as endangered under various laws and the expenditure on their protection). However, the best way to record this in ecosystem accounting has not yet been made clear in the SEEA.

Accounting for the difference in IVA due to trades-offs, the increase in economic activity from water yield and carbon sequestration (under a potential market) as known gains, surpasses (+AUD$8.5 million yr−1) the loss from native forest timber production (Fig. 4b). The addition of potential gains from tourism and plantation production further increase IVA.

Spatial distributions of ecosystem services of water provisioning, timber provisioning and carbon storage were derived and displayed as indices (Supplementary Figs. 2–4). These indices were combined to derive an interaction index (see Methods) that shows areas of common highest values of these ecosystem services, or ‘hotspots’ (Fig. 5a). The area of conflict is shown within the current land management tenure where the forest is available for harvesting (Fig. 5b). Mapping these ‘hotspots’ identified the locations where trade-offs in the use of ecosystem services are required.

The index combines values for water provisioning, native timber provisioning and carbon storage. Areas of highest values in red identify the ‘hotspots’, where maximum provisioning for native timber conflicts with maximizing services of water provisioning and carbon storage. a, All forest land in the study area. b, Forest area with land management tenure available for logging.

Discussion

Our application of ecosystem accounting provided new insights and understanding of complex trade-offs between competing land uses. Specifically, our approach enabled:

-

(1)

The contribution of ecosystem services to industries to be quantified in physical and monetary terms so that the services providing the greatest benefits could be identified and included in criteria for management decisions. In the Central Highlands region, water provisioning services, regulating services used in agricultural production, carbon sequestration, and cultural and recreational services should be prioritized, whereas native timber provisioning services had a lower value.

-

(2)

Greater transparency of costs and benefits by explicitly identifying ecosystem services that are subsidized. For example, water supply in the Central Highlands is subsidized through a fixed price and timber through low returns on investments made by the government. The benefits of these subsidized activities can be assessed in terms of efficient use of government funds and the identification of beneficiaries.

-

(3)

Identification of complementary or conflicting activities. Water supply, carbon sequestration, biodiversity conservation and nature-based tourism are complementary activities in the Central Highlands (agriculture and plantation forestry are located on different areas of land). Conversely, native forest timber production reduces the condition and value of forest assets for other activities.

-

(4)

Identification of additional policy and market instruments required to improve resource management. For example, carbon sequestration in native forests is an ecosystem service that occurs and benefits the public, but currently has no market because it is not included in Australian government regulations. Applying a market price for carbon in the case study identified the potential benefit of native forest protection as a carbon abatement activity.

Ecosystem accounting provides information about the stocks and stock changes of ecosystem assets and services, which can be quantified in physical and/or monetary terms. Monetary valuation of ecosystem services is a contentious issue23 because there are many characteristics of ecosystems that are not valued within the economy. Monetary valuation in ecosystem accounting is done for the purpose of comparison with national accounts.

This approach provides decision-makers with clear trade-offs. In the Central Highlands, a key question for decision-makers is whether reducing the risk of extinction of the Leadbeater’s possum is worth the AUD$12 million yr−1 that would be lost in IVA from the native forest industry if harvesting ceased. These economic losses could be offset by increases in the value of water provisioning and carbon sequestration. Downstream uses of native forest wood products could have alternative inputs; for example, the use of plantation timber and recycled paper. This analysis of trade-offs presents a concrete choice. It is different from the type of decision that could be made using contingent valuation22, which estimated the welfare value of the Leadbeater’s possum to be AUD$40–84 million yr−1 in 2000 (AUD$58–121 million yr−1 in 2015).

Monetary valuations in accounting do not necessarily assume substitutability among goods and services. Indeed, the estimated values of ecosystem services demonstrate their high value compared with the costs and, often impracticality, of technological substitutes24. Additionally, monetary valuation represents a minimum derived from the part of the ecosystem service that can be converted to a monetary metric. It does not include other services related to aesthetic, social, cultural, intrinsic or moral benefits. Protection of ecosystem assets and maintenance of flows of ecosystem services involve complex relationships and synergistic properties that cannot be entirely simplified in terms of monetary valuations23,24. Thus, monetary valuations of ecosystem services should be used judiciously in decision-making, recognising their limitations in terms of coverage of all benefits and complexities. The advantage of the ecosystem accounting methodology, comprising both monetary and physical metrics, is to enhance recognition of the contribution of ecosystems to economic activity and human well-being and start developing a system that incorporates these benefits into decision-making.

Because valuations of ecosystem services are not comprehensive, their purpose and appropriate methods of analysis must be clear6. Our motivation for analysis based on valuations was to demonstrate alternatives to the current system of land use and the impacts on different beneficiaries. The analysis showed that even partial valuation of some of the ecosystem services provided an economically viable alternative to native timber harvesting.

The identification and definition of specific ecosystem services, criteria for their selection and appropriate metrics present ongoing challenges for compiling accounts for a region23,25. Comprehensiveness in including all ecosystem services may not be possible in one study, but the relative importance of the services not included must be considered. In the Central Highlands, selection of ecosystem services included in the study was based on long-term research in the region, knowledge of data and knowledge of land management issues. Additionally, decisions about selection of metrics were pragmatic in terms of using available data; however, data are usually collected for the metrics considered most important by the experts in the field. For example, the measure of HBTs ha−1 is considered by ecologists to be a key indicator of suitable habitat for a range of species and, particularly, some critically endangered species26. Some of the ecosystem services not included explicitly were water filtration, air filtration, pollination, flood mitigation and soil erosion. Even with the ecosystem services that it was feasible to measure in our case study, their contributions to economic activities and human well-being could be demonstrated and the losses incurred if these ecosystem assets and services did not exist.

A particularly important distinction in the selection of appropriate metrics is the stock of an ecosystem asset compared with the flow of ecosystem services from the asset23. Carbon sequestration presents a good example. The ecosystem service of climate regulation in the land sector is the protection and increase of carbon stocks in vegetation and soils, and hence removal of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. The appropriate metric is net carbon stock change together with the longevity of the change, rather than the annual rate of change27,28. Assessment of the flow of the ecosystem service must ensure that the stock of the ecosystem asset is not reduced or degraded. Ecosystem accounting includes information about stocks and flows, and both must be considered in valuations.

A range of methods for monetary valuation for ecosystem accounting is recommended6,29,30. This is a developing area of research and there are advantages, disadvantages and practicalities for each method. Valuation of ecosystem services using the resource rent method, as applied in this study for agricultural and plantation timber production, takes no account of the sustainability of service flows. Some service flows may result in degradation or depletion of ecosystem capital, and hence are unsustainable. There is a risk that the results will underestimate the ‘true’ value of ecosystem services in terms of capturing all the relevant missing prices6. This method is not appropriate in the case of open-access resource management because there is no incentive for the owner of the resource to maximize resource rent6. The replacement cost method estimates the price of a single ecosystem service and does not have the capacity to include interactions among services, which are in fact an essential characteristic of ecosystems. Trading schemes, such as carbon markets, are subject to variability due to the regulatory settings of the market and may not equate to societal willingness to pay6, nor to overall social cost31,32.

The accounting approach is different from cost–benefit analysis in terms of objectives, methods of valuation and outputs. In accounting, changes are estimated in the physical extent and condition of assets and the services that flow from them. The results in accounts are a mixed presentation of physical and monetary metrics and thus produce a multiple bottom line. This reflects the fact that different categories of natural resources exist, and not all have monetary values. Where monetary metrics are used, they are based on exchange values. The outputs from accounts are designed for ongoing management processes, thus allowing for longitudinal analysis informing adaptive management. Cost–benefit analysis is based on welfare values that estimate utility and monetize all values that are aggregated to produce a single line answer29. Consumer surplus is included in the value; that is, the maximum amount that consumers would have paid if required, but did not pay because producers were willing to sell at lower prices or it was provided for free, for example, by governments. Cost–benefit analysis seeks to monetize potential changes in welfare brought about by different potential decisions at a single point in time. The best decision is the one that achieves the greatest net change in welfare as measured in monetary terms.

Ecosystem accounting presents a framework that can unify existing diverse data from monitoring environmental and economic activities in any region. It provides a consistent methodology for evaluating trade-offs between the uses of ecosystem assets and their services. It offers the capacity for a compelling foundation for decision-making about natural resource management by presenting an integrated picture of benefits of ecosystems to society based on metrics that matter to human well-being. The application of ecosystem accounts has major implications globally for better recognizing ecosystem services, identifying trade-offs to improve ecosystem condition and defining solutions to environmental–economic conflicts.

Challenges remain in designing, implementing and communicating the information in ecosystem accounts. The accounts are in the form of a mix of physical and monetary metrics because it is not yet possible to monetize the values of all ecosystem assets and services, as we have described for biodiversity. Indeed, it may not be possible to attribute monetary values fully, and the decision-making process will have to cope with a multiple bottom line for assets and trade-offs in different units of measurement for services. The monetary metrics used in accounts are transaction values to make them comparable with the SNA; however, this means that potential improvements in welfare from the ecosystem services are not included. Attempting to include the values for comprehensive ecosystem assets and services within the decision-making process, even with the range of metrics, is an advance from the current situation where most ecosystem values are not included.

Our novel approach to ecosystem accounts compares values of ecosystem services and their contribution to GDP across natural resource sectors, and this has informed decision-making about the relative values of conflicting activities in the region. The imperative is to include the contribution of ecosystem services to human well-being in policy development and decision-making before they are lost through degradation and depletion. In this way, the success of human enterprise can be directed to a more sustainable trajectory, rather than one solely dependent on economic growth.

Methods

Study region

The Central Highlands region in Victoria is approximately 100 km northeast of Melbourne. The region is 735,655 ha in area and consists predominantly of native forest on public land, with about half currently managed for wood production and half for conservation. Public land in Australia used for commercial native timber production is managed under Federal–State Government agreements33. These agreements, reached through protracted and controversial processes involving debates among public, industry, government and non-government organizations, will expire within two years. Hence, improved decision-making processes are imperative. The issue of specific concern in the Central Highlands is a proposal to expand protected areas for conservation of endangered species, particularly the critically endangered Leadbeater’s possum, and recreational amenity.

Physical supply of ecosystem services

The region provides ecosystem services both within the study area and in surrounding rural areas and the city. These ecosystem services were quantified in terms of physical metrics of stocks and stock changes. Native forest harvesting provides timber and paper products and employment; regional employment is a key social, economic and political factor. The forested catchments provide the main urban water supply for Melbourne and rural water supply for agricultural areas, which are becoming increasingly threatened by droughts34. The temperate, evergreen forests have a high carbon density and thus maximizing their carbon storage is an important climate change mitigation activity35. Tourism is an increasing source of economic activity and employment in the region, particularly due to the proximity of Melbourne36. Part of the region is used for agricultural production and plantation forestry is expanding37.

Water provisioning service

The water provisioning service is described in physical terms by the runoff or water yield from the catchments in the study area, which provide inflows to the reservoirs operated by Melbourne Water. Water yield was calculated across the study area and provided information about the spatial distribution across the landscape and annual changes in response to climate variability, land cover change and disturbance history.

Water yield was estimated each year using a spatially explicit continental water balance model calculated monthly across the study area38,39 (see details in Supplementary Methods). Calculation of water yield used the balance between rainfall and evapotranspiration, soil water storage capacity and vegetation cover. Although more detailed hydrological models exist (for example, refs 40,41), the advantage of using the model based on eMAST data is that it is applicable nationally and the same method can be used for developing water accounts in any region.

Water yield in the catchments is driven by precipitation and evaporation, but it is also influenced by the condition of the vegetation, with the main factor being the age of the forest. Evapotranspiration depends on leaf area index and leaf conductance, which vary with forest age and thereby determine the shape of the water yield response curve42. Forest age was determined from the last stand-replacing disturbance event, which refers to high severity fire or clearfell logging for montane ash forest and rainforest and clearfell logging for mixed species forest. The response of water yield to forest age was derived from a synthesis of information from the literature40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49. Change in water yield is estimated as a proportion of the pre-disturbance amount (Supplementary Fig. 1). An increase in water yield occurs for the first one to five years after stand-replacing disturbance in all forest types. In montane ash forest and rainforest, a decrease in water yield then occurs because the regenerating forest with dense leaf growth results in high water use by transpiration. The greatest reduction occurs between the ages of 13 and 49 years and peaks at 25 years. Maximum reduction from a pre-disturbance 1939 regrowth forest is 29%, and from an old growth forest is 48%. Water yield is not fully restored for at least 80 years if a forest is regrowth at the time it is disturbed, and this takes 200 years if a forest is defined as old growth at the time it is disturbed.

The water yield calculated from the water balance model was derived for a constant vegetation condition, thus producing a baseline yield. This baseline yield was compared with the yield when forest age and the change in age were taken into account. The difference in water yield with and without disturbance events, disaggregated into fire and logging events, allowed attribution of the change in water yield. This information was used to analyse the change in water yield in the counterfactual case, where logging had not occurred in the catchments. Details of calculations of the water yield function with forest age taken into account are provided in the Supplementary Methods.

Carbon stocks and stock changes

Carbon stocks in biomass were estimated for the following components: above- and below-ground biomass and living and dead biomass (insufficient data exist to estimate soil carbon spatially and temporally). A model of biomass carbon stock estimated spatially across the landscape was derived for montane ash forests in eastern Victoria using spatial biophysical data calibrated with site data (n = 930 sites) of biomass carbon stocks calculated from tree measurements50. Carbon stocks were derived in relation to the environmental conditions at the site, forest type, age of the forest since the last stand-replacing disturbance event and previous disturbance history of logging and fire. Modelled carbon stocks were restricted to within the range of the calibration site data. For the carbon accounts in the current study within a defined regional boundary, additional carbon data were included for all land cover types within the study area to derive a base carbon stock map. Carbon stocks were calculated for each grid cell related to spatial variation in environmental conditions and based on the matrix of land cover types, forest age and disturbance history (Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Table 1).

The change in carbon stock over time was calculated from the base carbon stock map for the land cover condition pre-2009 fire, and then using forward projections from 2009 to 2015 and backwards projections from 2009 to 1990. Changes in carbon stocks resulted from growth of trees, emissions due to fire, collapse of dead standing trees, decomposition of dead biomass and losses due to logging. Functions describing these processes are provided in the Supplementary Methods. The net carbon stock change is the balance between additions due to growth and reductions due to combustion, decomposition and removal of stocks from the site.

Native forest timber provisioning

Data about wood resources harvested from native forests were sourced from the government agency responsible for managing the resource, VicForests. Data included the area harvested, wood yield and wood volume for each forest type and product type over time (1990–2014).

Plantation timber provisioning

Estimates of wood product volume and yield were derived from a national carbon accounting model51, national data52 and data from the softwood plantation company53. Areas of hardwood and softwood plantations were derived from the land use spatial data.

Regulating services used in agricultural production

The ecosystem services used for crop production and fodder for livestock include pollination, abstraction of water, soil nutrient uptake and nitrogen fixation6. Some of these services would have been generated on the land used for agricultural production (soil water and nutrient uptake), whereas others may have been generated elsewhere (for example, pollination). For this account, all ecosystem services produced (supplied) were allocated to the agricultural land cover.

Cultural and recreational services

The Central Highlands are used for various recreational purposes. The region includes national parks and other reserves, as well as wineries and other tourist attractions. As an example, visitation to national parks in the study area was approximately 750,000 in 2010–2011 (ref. 54).

Habitat provisioning services

One of the key services provided by native forests is nest sites for animals and birds, which were measured using values of HBTs ha–1 (refs 26,55). Numbers of arboreal marsupial animals, including the critically endangered Leadbeater’s possum and HBTs were monitored at 161 sites of different age classes of regenerating forest after logging and old growth forest, over a 28 year period. Several biodiversity metrics were compiled into accounts, including the total number of species, lists of threatened species, the change in listed species and their threat categories over time, the abundance and species diversity of arboreal marsupials and HBTs in a range of forest age classes.

Valuation of ecosystem services

Where appropriate, the physical metrics of ecosystem services were converted to a value in monetary terms as the physical quantity multiplied by the price. Valuation of ecosystem services is complex because they are generally not exchanged within markets like other goods and services. Therefore, economic principles must be applied to estimate the ‘missing prices’ or prices that are implicitly embedded in values of marketed goods and services6. Approaches to monetary valuation of ecosystem services depend on the type of ecosystem service and the data available, and a range of methods were applied in the Central Highlands.

Water provisioning service

The value of water provisioning service is equal to the volume of water inflows multiplied by the price per unit of the service. The cost of the ecosystem service was estimated from the replacement value of an alternative source if water was not available from the catchments56. This method assumes that (1) if the service was lost it would be replaced by users and (2) users would not change their pattern of use in response to a price increase.

The resource rent approach could not be used for water because data were not available for the value of water supply infrastructure and the associated costs of supply. Information about the costs of water supply is not separated from the costs of sewerage. In addition, the price of water is regulated by the Essential Services Commission57, and hence the seller’s price is constrained. The production function approach to valuation was also rejected for this study because of a lack of data, which would require detailed information about prices paid by water retailers and subsequent water consumers, as well as the value of all other inputs to the productive activities of the businesses.

Calculation of the water provisioning service as a replacement cost is a method to estimate the price per unit of water. This method does not assume, however, that complete replacement is a viable option for water provisioning. The transfer of water from another region would not provide sufficient supply to meet the demand from Melbourne and would impact water supply in the other region. The existing desalination plant at Wonthaggi does not have the capacity to meet the total demand, and other impacts of constructing and operating the plant, such as energy demand and greenhouse gas emissions, are not taken into account. The use of recycled water would not provide sufficient quantity of a product of the same quality and the process would require high-energy inputs.

Carbon sequestration

The positive net change in carbon stocks represents the ecosystem service of carbon sequestration because carbon dioxide is removed from the atmosphere and stored in a terrestrial ecosystem. The negative net change in carbon stocks or emissions represents the contribution of the land use activity to the national greenhouse gas emissions. A market-based system to offset the negative environmental impacts of greenhouse gas emissions used the net amount of carbon sequestered each year58. A potential valuation was applied based on the current Australian government market price for abatement of CO2 emissions. The time series for carbon sequestration reflects changes in carbon stocks, but the price is based on the November 2015 auction value of AUD$12.25 per tonne of CO2-equivalent emissions (ref. 58), which was adjusted for inflation, but did not include potential changes in the price.

The trade-off in carbon sequestration, analysed for the counterfactual case where harvesting ceased, was continued carbon stock gain as forest age increased, according to the forest growth functions. The difference in net change in carbon stock density between the area logged and the area unlogged but available for logging indicated the carbon sequestration potential.

Native forest timber provisioning service

A market price was calculated as the volume of timber harvested each year and the reported stumpage value (that is, the revenue from log sales less harvesting and haulage costs)59. The area and volume harvested in the study area were used to calculate the percentage of the state total contributed by the study area, which was then applied to the state financial data.

Plantation timber provisioning service

Data for the gross value of hardwood and softwood products52 were used for the State of Victoria and scaled to the study area based on the ratio of areas of each type of plantation within the study area and state. A value was derived for the use of ecosystem services in the production of plantation timber, because the plantation is within the production boundary of the market19. Unit resource rent was calculated from Australian industry production data for the subdivision of forestry and logging, based on the gross operating surplus and mixed income, consumption of fixed capital and return on fixed capital60. Resource rent as a percent of gross operating surplus was multiplied by IVA to estimate the value of the ecosystem services contributing to production.

Regulating services used in agricultural production

The resource rent method61 was used to value the regulating services used in agricultural production. Data on the volume, value and costs of production for agriculture were available for statistical areas, the state and nationally, respectively62,63. Each dataset was downscaled to the study area. This method has been used by the Australian Bureau of Statistics for similar accounting exercises. The unit resource rent is the difference between the benefit price and the unit costs of labour, produced assets and intermediate inputs6. These calculations assume that the percentage of the gross value of agricultural production from the Central Highlands compared with Victoria and the costs of production compared nationally are appropriate scalers. Additionally, the level of resource rent generated from the Central Highlands is similar to the rest of Australia. These assumptions are not likely to be accurate, but are probably broadly indicative of the level of services provided.

Cultural and recreational services

The use of cultural and recreational services by people can be valued as part of the value to the area of the consumption by tourists. This consumption relies not just on the ecosystem services, but also capital, labour and other inputs from the industries supporting tourists; for example, restaurants and accommodation. The State of Victoria has produced regional tourism satellite accounts36. Values for the Central Highlands study area were estimated by applying the fraction of area of the tourism regions within the study area to the data in the tourism accounts. The cultural and recreational ecosystem services were estimated using the resource rent approach, using coefficients of resource rent to total output that are used by the Australian Bureau of Statistics64.

Valuation of industries

The key principle of valuation of economic activity is the exchange value, which is used when transactions are valued at the price at which they were exchanged. Total value is the price multiplied by the quantity sold, where the price usually represents the production cost plus a profit to the producer. An exchange value is distinct from the notion of value used in welfare economics, which is associated with utility and includes a consumer surplus.

For ecosystem services that are included in the market system, IVA is a standard metric used to quantify the economic activity of industries and represents their contribution to GDP (that is, IVA is part of the SNA)65. The IVA metric is calculated as the revenue from sales less costs, or the wages and profit before tax and fixed capital consumption. IVA is derived for industries that produce goods and services that are traded within the economy. In this study, these industries included native forest and plantation timber, water, agricultural commodities, and the goods and services associated with tourism. This economic information is recorded in publications by the Australian Bureau of Statistics and in annual reports of government agencies59,66.

Water supply

Water supplied from the reservoirs to consumers within the economy was valued as the revenue earned by Melbourne Water. Water supply includes drinking water, environmental releases, irrigation entitlements and extra allocations. Data are reported by Melbourne Water66 for the volume of water supplied, the revenue received from this supply and the costs of producing the water (wages and salaries, consumption of fixed capital and other running costs; for example, for reservoirs, water mains, pumps, and so on). These data were used to generate an estimate of the IVA for water supply.

Carbon sequestration

There is no exchange value for carbon sequestration in native forests because forest protection is not an approved abatement activity under the Australian Government regulations67. However, carbon is sequestered by forests and this benefits the public through climate change mitigation, and through the state and national emissions reduction targets. Hence, a value of carbon sequestration can be estimated if market access were permitted under the Emissions Reduction Fund (https://www.environment.gov.au/climate-change/emissions-reduction-fund). Based on SNA approaches to valuation when market prices are not observable, the SEEA6 uses a market price equivalent, which is usually based on the market price of similar goods or services. In the case of carbon sequestration, the price of carbon abatement is set by government auction irrespective of the activity or methodology for abatement58. This carbon price is equivalent to the revenue from production. The IVA is estimated from revenue from carbon sequestration less costs of managing the forest. Managing the forest for carbon storage was assumed similar to that for a national park and costs were estimated from the financial accounts of Parks Victoria68.

Native timber supply

The revenue from native timber supply is reported by VicForests59. IVA was calculated as the sum of wages, employee benefits, depreciation, amortisation and net operating result before tax.

Plantation timber supply

IVA was calculated from the total industry output for hardwood and softwood plantations less the intermediate consumption60, scaled to the study area.

Agricultural production

IVA was calculated from the total industry output for agricultural production less the intermediate consumption62, scaled to the study area.

Tourism

The regional tourism satellite accounts36 provided data for IVA and these were scaled to the study area.

Spatial distribution of ecosystem services

Spatial distributions of ecosystem services were derived from their physical metrics in relation to land cover, land use and the environmental conditions across the landscape. They were calculated for water provisioning (Supplementary Fig. 2), carbon storage (Supplementary Fig. 3) and native timber provisioning (Supplementary Fig. 4).

The value of the timber provisioning service was derived from the forest age weighted by forest type. Forest age was calculated from the last regeneration event and range-normalized to an index between 0 and 1. The forest age index was multiplied by a weighting for forest type (ash = 1; wet, mixed species = 0.667; open, mixed species = 0.333). The physical metrics for carbon storage (tC ha−1) and water yield (ML yr−1) are continuous variables that were range-normalized to indices between 0 and 1. The interaction of the values of ecosystem services was derived from the product of these three component indices. This interaction index showed the areas of relatively highest value or ‘hotspots’.

The indices are continuous from 0 to 1, but are displayed on the map (Fig. 5) as five classes for ease of comparison. Classification used the Jenks natural breaks optimization function in ArcGIS. This is a data clustering method designed to reduce the variance within classes and maximize the variance between classes. Because the data are highly skewed, this classification produced more even classes than using equal class sizes.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the Supplementary Methods and a full report from https://tsrhub.worldsecuresystems.com/Ecosystem%20Complete%20Report_V5_highest%20quality.pdfand https://tsrhub.worldsecuresystems.com/Ecosystem%20Appendices_V6_highest%20quality.pdf./.

References

Oreskes, N. & Conway, E. M. Merchants of Doubt (Bloomsbury Press, New York, 2010).

Pielke, R. S. The Honest Broker: Making Sense of Science in Policy and Politics (Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, 2007).

Saner, M. A. & Bordt, M. Building the consensus: the moral space of earth measurement. Ecol. Econ. 130, 74–81 (2016).

Sustainable Development Goals (United Nations, 2015); http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/.

System of Environmental–Economic Accounting 2012: Central Framework (United Nations, 2014); http://unstats.un.org/unsd/envaccounting/seeaRev/SEEA_CF_Final_en.pdf.

System of Environmental–Economic Accounting 2012: Experimental Ecosystem Accounting (United Nations, 2014); http://unstats.un.org/unsd/envaccounting/seeaRev/eea_final_en.pdf.

System of National Accounts 2008 (United Nations, 2009); https://unstats.un.org/unsd/nationalaccount/docs/SNA2008.pdf.

Repetto, R. Wasting assets: the need for national resource accounting. Tech. Rev. 93, 38–45 (1990).

Ouyang, Z. et al. Improvements in ecosystems services from investments in natural capital. Science 352, 1455–1459 (2016).

Vardon, M., Burnett, P. & Dovers, S. The accounting push and pull: balancing environment and economic decisions. Ecol. Econ. 124, 145–155 (2016).

Ruckelshaus, M. et al. Notes from the field: lessons learned from using ecosystem service approaches to inform real-world decisions. Ecol. Econ. 115, 11–21 (2015).

De Groot, R. S., Alkemade, R., Braat, L., Hein, L. & Willemen, L. Challenges in integrating the concept of ecosystem services and values in landscape planning, management and decision making. Ecol. Complex. 7, 260–272 (2010).

Costanza, R. et al. The value of the world’s ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature 387, 253–260 (1997).

Daily, G. C. et al. Ecosystem services in decision making: time to deliver. Ecosys. Serv. 7, 21–28 (2009).

Ma, S. et al. Valuation of ecosystem services to inform management of multiple-use landscapes. Ecosys. Serv. 19, 6–18 (2016).

Bateman, I. et al. Bringing ecosystem services into economic decision-making: land use in the United Kingdom. Science 341, 45–50 (2013).

Obst, C., Edens, B. & Hein, L. Ecosystem services: accounting standards. Science 342, 420 (2013).

Fisher, B., Turner, R. K. & Morling, P. Defining and classifying ecosystem services for decision making. Ecol. Econom. 68, 643–653 (2009).

European Environment Agency CICES: Towards a Common Classification of Ecosystem Services (Common International Classification of Ecosystem Services, 2016); http://www.cices.eu.

Lindenmayer, D. B. et al. Interacting factors driving a major loss of large trees with cavities in a forest ecosystem. PLoS ONE 7, e41864 (2012).

Great Forest National Park: Economic Contribution of Park Establishment, Park Management, and Visitor Expenditure (Nous Group, 2017); http://www.greatforestnationalpark.com.au/uploads/1/5/5/7/15574924/nous_gfnp_economic_contribution_study_3_february_2017.pdf.

Jakobsson, K. M. & Dragun, A. K. The worth of a possum: valuing species with the contingent valuation method. Environ. Res. Econ. 19, 211–227 (2001).

Vira, B. & Adams, W. M. Ecosystem services and conservation strategy: beware the silver bullet. Conserv. Lett. 2, 158–162 (2009).

Chee, Y. E. An ecological perspective on the valuation of ecosystem services. Biol. Conserv. 120, 549–565 (2004).

Van Oudenhoven, A. P. E., Petz, K., Alkemande, R., Hein, L. & de Groot, R. S. Framework for systematic indicator selection to assess effects of land management on ecosystem services. Ecol. Indicators 21, 110–122 (2012).

Lindenmayer, D. B. et al. An empirical assessment and comparison of species-based and habitat-based surrogates: a case study of forest vertebrates and large old trees. PLoS ONE 9, e89807 (2014).

Ajani, J., Keith, H., Blakers, M., Mackey, B. G. & King, H. P. Comprehensive carbon stock and flow accounting: a national framework to support climate change mitigation policy. Ecol. Econ. 89, 61–72 (2013).

Mackey, B. et al. Untangling the confusion around land carbon science and climate change mitigation policy. Nat. Clim. Change 3, 552–557 (2013).

Obst, C., Hein, L. & Edens, B. National accounting and the valuation of ecosystem assets and their services. Environ. Res. Econ. 64, 1–23 (2016).

Castañeda, J. P., Obst, C., Varela, E., Barrios, J. M. & Narloch, U. Forest Accounting Sourcebook. Policy Applications and Basic Compilation. (World Bank, Washington, DC, 2017).

Tol, R. S. J. The marginal damage costs of carbon dioxide emissions: an assessment of the uncertainties. Energy Pol. 33, 2064–2074 (2005).

Valuing Climate Damages: Updating Estimation of the Social Cost of Carbon Dioxide (The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, 2017); https://www.nap.edu/catalog/24651/valuing-climate-damages-updating-estimation-of-the-social-cost-of.

Regional Forest Agreements (Australian Government Department of Agriculture and Water Resources, 2016); http://www.agriculture.gov.au/forestry/policies/rfa.

Viggers, J. L., Weaver, H. J. & Lindenmayer, D. B. Melbourne’s Water Catchments Perspectives on a World-Class Water Supply. (CSIRO Publishing, Collingwood, 2013).

Keith, H., Mackey, B. G. & Lindenmayer, D. B. Re-evaluation of forest biomass carbon stocks and lessons from the world’s most carbon-dense forests. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 11635–11640 (2009).

Value of Tourism to Victoria’s Regions 2013–14 (Tourism Victoria, 2015); http://www.tourism.vic.gov.au/component/edocman/?view=documenttask=document.downloadid=941.

Victorian Land Use Information System 2014/2015 (Government of Victoria, 2015); https://www.data.vic.gov.au/data/dataset/victorian-land-use-information-system-2014-2015.

Guo, S., Wang, J., Xiong, L., Ying, A. & Li, D. A macro-scale and semi-distributed monthly water balance model to predict climate change impacts in China. J. Hydrol. 268, 1–15 (2002).

eMAST R-package 2.0 (TERN, 2016); http://www.emast.org.au/observations/bioclimate/.

Feikema, P. M. et al. Hydrolgical Studies into the Impact of Timber Harvesting on Water Yield in State Forests Supplying Water to Melbourne (eWater Cooperative Research Centre, Canberra, 2006).

Feikema, P. M., Sherwin, C. B. & Lane, P. N. J. Influence of climate, fire severity and forest mortality on predictions of long term streamflow: potential effect of the 2009 wildfire on Melbourne’s water supply catchments. J. Hydrol. 488, 1–16 (2013).

Vertessy, R. A., Watson, F. G. R. & O’Sullivan, S. K. Factors determining relations between stand age and catchment water balance in mountain ash forests. For. Ecol. Manage. 143, 13–26 (2001).

Kuczera, G. Prediction of Water Yield Reductions Following a Bushfire in Ash – Mixed Species Eucalypt Forest Report No. MMBW-W-0014 (Melbourne Metropolitan Board of Works, 1985).

Kuczera, G. Prediction of water yield reductions following a bushfire in ash-mixed species eucalypt forest. J. Hydrol. 94, 215–236 (1987).

Vertessy, R. A., Hatton, T. J., Benyon, R. G. & Dawes, W. R. Long-term growth and water balance predictions for a mountain ash (Eucalyptus regnans) forest catchment subject to clear-felling and regeneration. Tree Physiol. 16, 221–232 (1996).

Watson, F. G. R., Vertessy, R. A. & Grayson, R. B. Large-scale modelling of forest hydrological processes and their long-term effect on water yield. Hydrol. Proc. 13, 689–700 (1999a).

Watson, F., Vertessy, R., McMahon, T., Rhodes, B. & Watson, I. Improved methods to assess water yield changes from paired-catchment studies: application to the Maroondah catchments. For. Ecol. Manage. 143, 189–204 (2001).

Lane, P. N. J., Feikema, P. M., Sherwin, C. B., Peel, M. C. & Freebairn, A. C. Modelling the long term water yield impact of wildfire and other forest disturbance in Eucalypt forests. Environ. Mod. Soft. 25, 467–478 (2010).

Buckley, T. N., Turnbull, T. L., Pfautsch, S., Gharun, M. & Adams, M. A. Differences in water use between mature and post-fire regrowth stands of subalpine Eucalyptus delegatensis R. Baker. For. Ecol. Manage. 270, 1–10 (2012).

Keith, H., Mackey, B. G., Berry, S., Lindenmayer, D. B. & Gibbons, P. Estimating carbon carrying capacity in natural forest ecosystems across heterogeneous landscapes: addressing sources of error. Global Change Biol. 16, 2971–2989 (2010).

Land Sector Reporting: Full Carbon Accounting Model (FullCAM) (Australian Government Department of the Environment and Energy, 2015); https://www.environment.gov.au/climate-change/greenhouse-gas-measurement/land-sector.

Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences Australian Plantation Statistics 2016 (Australian Government Department of Agriculture and Water Resources, Canberra, 2016); http://data.daff.gov.au/data/warehouse/aplnsd9ablf002/aplnsd9ablf201608/AustPlantationStats_2016_v.1.0.0.pdf.

2016/17 Forest Management Plan (HVP Plantations, 2016); https://www.hvp.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/2016_17-HVP-FOREST-MANAGEMENT-PLAN.pdf.

Varcoe, T., O’Shea, H. B. & Contreras, Z. Valuing Victoria’s Parks: Accounting for Ecosystems and Valuing their Benefits: Report of the First Phase Findings (Parks Victoria & Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, Victorian Government, 2015).

Lindenmayer, D. B., Cunningham, R. B., Tanton, M. T., Smith, A. P. & Nix, H. A. Characteristics of hollow-bearing trees occupied by arboreal marsupials in the montane ash forests of the Central Highlands of Victoria, south-east Australia. For. Ecol. Manage. 40, 289–308 (1991).

Edens, B. & Graveland, C. Experimental valuation of Dutch water resources according to SNA and SEEA. Water Res. Econ. 7, 66–81 (2014).

2008 Waterways Water Plan (Melbourne Water, 2008); http://www.esc.vic.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/esc/64/64055944-d4cf-4a27-96c7-01e4bc27bcd8.pdf.

Auction – November 2015. Clean Energy Regulator (21 November, 2016); http://www.cleanenergyregulator.gov.au/ERF/Auctions-results/November-2015.

Corporate Reporting: Annual Reports 2007-2015 (VicForests, 2015); http://www.vicforests.com.au/our-organization/corporate-reporting-5.

5204.0 - Australian System of National Accounts, 2015-16. Table 58 Capital Stock by Industry and Table 65 Consumption of Fixed Capital by Industry by Type of Asset (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2017); http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/5204.02015-16?OpenDocument. Disaggregated data for Subdivision 03 Forestry and Logging available on request from the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

Australian Environmental–Economic Accounts (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2014); http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/4655.0.

2010–11: Value of Principal Agricultural Commodities Produced: Australia, Preliminary (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2011); http://www.ausstats.abs.gov.au/ausstats/subscriber.nsf/0/F6F20CFC59C07E0DCA25794A0011F935/$File/75010_2010_11.pdf.

Value of Agricultural Commodities Produced, Australia. (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2016); http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/PrimaryMainFeatures/7503.0?OpenDocument.

An Experimental Ecosystem Account for the Great Barrier Reef Region, 2015 (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2015); http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS%5Cabs@.nsf/0/FB46321B5BA1A8EACA257E2800174158?Opendocument.

Australian System of National Accounts (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2016); (ABS Cat. No. 5204.0); http://www.abs.gov.au/AusStats/ABS@.nsf/MF/5204.0.

Annual Report Archive (Melbourne Water, 2000-2015); http://www.melbournewater.com.au/aboutus/reportsandpublications/Annual-Report/Pages/Annual-Report-archive.aspx.

Sequestration Decision Tree. Emissions Reduction Fund, Opportunities for the Land Sector (Clean Energy Regulator, (2016); http://www.cleanenergyregulator.gov.au/DocumentAssets/Documents/Sequestration%20decision%20tree%202016.pdf.

Annual Report 2013-2014 (Parks Victoria, State Government of Victoria); http://parkweb.vic.gov.au/about-us/publications-list/annual-reports.

Acknowledgements

Support for this project was provided by research funding from Fujitsu Laboratories, Japan, and the National Environmental Science Programme of the Australian Department of the Environment and Energy and is gratefully acknowledged. We thank staff at the Australian Bureau of Statistics, the Victorian Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, and VicForests for assistance with access to data and its interpretation. This research was undertaken with the assistance of resources from the Australian Government’s National Collaborative Research Infrastructure Strategy through its Terrestrial Ecosystem Research Network programme and the National Computational Infrastructure programme. We thank participants who attended a workshop in Melbourne in August 2016 for constructive feedback on the study, C. Hilliker for expert assistance with graphics and P. Burnett for helpful comments on a draft of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.K., M.V. and D.L. designed the study. H.K. and M.V. performed the calculations. J.A.S. performed the spatial analysis. J.L.S. performed the hydrological modelling. The manuscript was written by H.K. with contributions from M.V. and D.L.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Methods, Supplementary Figures 1–4, Supplementary Tables 1–3, Supplementary Glossary, Supplementary References

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Keith, H., Vardon, M., Stein, J.A. et al. Ecosystem accounts define explicit and spatial trade-offs for managing natural resources. Nat Ecol Evol 1, 1683–1692 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-017-0309-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-017-0309-1

This article is cited by

-

Recognizing First Nations' values in natural capital accounting benefits all

Communications Earth & Environment (2025)

-

Synergies and complementarities between ecosystem accounting and the Red List of Ecosystems

Nature Ecology & Evolution (2024)

-

Balancing the books of nature by accounting for ecosystem condition following ecological restoration

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

From COVID-19 to Green Recovery with natural capital accounting

Ambio (2023)

-

Why We Need to Invest in Large-Scale, Long-Term Monitoring Programs in Landscape Ecology and Conservation Biology

Current Landscape Ecology Reports (2022)