Abstract

Freshwater ecosystems, particularly rivers, are experiencing the most rapid biodiversity declines of any biome, driven by several interacting stressors operating across local to global scales. Despite growing research on these interactions, the lack of systematic quantification of individual stressor gradients limits our ability to disentangle their cumulative effects. Here we present a global synthesis of stressor–response relationships across five key riverine organism groups—prokaryotes, algae, macrophytes, invertebrates and fish. We screened 22,120 papers and extracted 276 studies with 1,332 stressor–response relationships. We used generalized linear mixed models and Bayesian meta-analyses to quantify the response to the seven most prevalent stressors. Consistently across taxa, biodiversity loss (taxon richness and evenness) reflected elevated salinity, oxygen depletion and fine sediment accumulation, while the association with nutrient enrichment and warming varied among groups. Predictive tools, including hypothetical outcome plots and partial dependence plots, revealed the interplay of stressors and predicted biodiversity response to stress increase. Our findings establish a quantitative baseline for a continuous global synthesis, refining predictions of anthropogenic stressor impacts, identifying key research gaps and informing conservation strategies for freshwater ecosystems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Freshwater ecosystems—particularly rivers—have undergone rapid biodiversity declines in recent decades, driven by several interacting stressors across local, catchment and global scales1,2. Agricultural intensification, urban wastewater and sewer overflows degrade water quality3,4,5, while water abstraction exacerbates droughts and impervious surfaces intensify flash floods6. Other catchment-scale pressures, such as land reclamation, hydropower generation and navigation, further degrade habitat structure7,8. Meanwhile, global change further intensifies these impacts by disrupting flow regimes and thermal dynamics, compounding local pressures9,10. All these stressors may interact in complex ways, shaping the composition and diversity of riverine communities and making it challenging to predict biodiversity responses. Understanding these relations and the underlying mechanisms is crucial for effective conservation and management.

Over the past decade, research has increasingly focused on the cumulative effects of several stressors on riverine biodiversity. For example, Lemm et al.11 found that the ecological status of European rivers declines with increasing intensity of several stressors, while Brauns et al.12 demonstrated how several stressors impair ecosystem functioning. Experimental studies have explored how stressors interact—whether their effects are additive, synergistic or antagonistic—and investigated the underlying mechanisms13,14,15. However, despite substantial progress, a generalizable framework for predicting how several stressors collectively shape biodiversity remains elusive. This would require information, ideally raw data, on the relation between various organism groups and stressors from a range of ecoregions and river types, and a model that accounts for these multivariable data and the associated bias.

Paradoxically, the focus on multistressor impacts has obscured a critical knowledge gap: the absolute effects of individual stressors and their interactions with specific organism groups remain poorly quantified. Although numerous studies have examined individual stressor–response relationships15 and one global synthesis compared terrestrial, marine and freshwater communities16, a quantitative assessment across aquatic organism groups and stressors is still lacking.

Stressors affecting aquatic organisms can be broadly categorized as physicochemical stressors, which alter water quality and hydromorphological stressors, which modify habitat structure. Each stressor operates through distinct modes of action that may be caused by specific cellular mechanisms or through the provision/removal of habitats and that exclude or favour certain species. For instance, oxygen depletion slows metabolism17,18, while elevated salinity disrupts osmoregulation19. Hydromorphological changes, such as fine sediment accumulation or channelization, alter habitat availability, favouring some species while excluding others20.

The sensitivity of riverine organisms to these stressors varies widely. Larger organisms, such as fish and macrophytes, are disproportionately affected by habitat modifications including associated dispersal constraints21,22, while physicochemical stressors such as oxygen depletion and warming can affect a broader range of taxa23,24. Yet, systematic comparisons of stressor associations across different taxonomic groups remain rare20,22, limiting our ability to extrapolate localized findings to broader ecological contexts.

To address this gap, we present a global synthesis of stressor–response relationships across five key riverine organism groups—bacteria/archaea, algae, macrophytes, invertebrates and fish—focusing on seven widespread stressors. Drawing from 22,120 observational studies, we compiled 276 datasets encompassing 1,332 distinct stressor–response relationships. Each study sampled a riverine community at least six times (median = 14, mean = 58, s.d. = 346) focusing on at least one stressor (median = 3, mean = 3.3, s.d. = 2.5). We did not include experimental studies, as our prime interest lies in the relationship between stressors and biota under real-world conditions. Using multivariable generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs) and Bayesian meta-analyses, we quantified the associations of individual stressors and identified overarching response patterns.

This analysis provides a quantitative baseline for a continuous, global assessment of freshwater stressor impacts, enhancing our ability to predict biodiversity responses under increasing anthropogenic pressures. The prime objective was to establish empirical relationships between stressor intensity and biodiversity metrics over a wide range of conditions, independently of possible causes. Our findings offer crucial insights for conservation planning, informing mitigation strategies tailored to specific stressors and organism groups. By systematically quantifying stressor–response relationships, we contribute to a more predictive and actionable understanding of riverine ecosystem resilience in the face of accelerating environmental change.

Results and discussion

A global perspective on stressor–response relationships

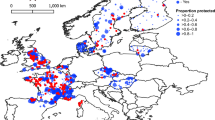

Our meta-analysis revealed 1,332 stressor–response relationships from 276 studies across 87 countries (Fig. 1).

a,b, Geographic distribution of data sources included in this synthesis (a) and breakdown of stressor categories by organism groups (b). Map data from Natural Earth (http://www.naturalearthdata.com).

Nearly half the identified stressor–response relationships focused on invertebrates, with salinity and temperature being the most frequently studied stressors. In contrast, hydromorphological stressors—despite their recognized ecological importance11—were under-represented (Fig. 1), underscoring a critical research gap.

Taxonomic richness (for example, species or genus counts) that were analysed with log-linear models prevailed (92.9%), while for all logit-linear models evenness prevailed (71%) (Supplementary Table 4). In many individual studies, the relationships between stressors and biological responses varied greatly, often showing substantial heterogeneity. Although some stressor–response patterns are evident, the overall relations were relatively modest and highly variable for different stressors and organism groups. This highlights the inherent complexity of interpreting stressor–response dynamics in ecological systems (compare Supplementary Data 2).

Relations of biodiversity patterns to single and combined stressor gradients

Only invertebrates consistently showed strong and negative relations to all stressors, except phosphorus enrichment, reflecting their dependence on oxygen availability, habitat structure and stable flow conditions25,26,27. In contrast to invertebrates, microorganisms—particularly bacteria/archaea—showed more variable patterns, probably due to their dependence on microscale conditions and the limited availability of suitable datasets28,29,30. Fish exhibited a mix of positive and negative stressor–response relationships, while relations of macrophytes to oxygen depletion and flow is opposing those of other groups, emphasizing their unique adaptations as sessile autotrophs (Fig. 2). However, our meta-analysis necessarily obscures divergent patterns of macrophytic taxa, such as bryophytes and vascular plants, which vary substantially in evolutionary origins, traits and environmental requirements.

Posterior probability distributions (approximately the same as frequency of simulations) of regression coefficients for stressor–response relationships across five organism groups and seven stressors. a,b, Regression coefficients from log-linear models for taxonomic richness (a) and logit-linear models for evenness/coverage (b). Dots represent the mode, known as the MAP estimate; horizontal bars indicate 90% high-density intervals. Blue curves indicate positive mode estimates (approximately the same as positive response of organism group to stressor), while red curves indicate negative estimates. Full posterior results are given in Supplementary Data 2.

Microbial responses require a dedicated sampling strategy to reflect microscale patterns. The response of bacteria/archaea was often divergent compared with macroorganisms, probably due to their environmental specificity and the under-representation of relevant studies. This includes methodological challenges to designate species and to assign operational taxonomic units that respond to stressor intensities. Notably, bacterial diversity exhibited a positive relationship with temperature, consistent with findings in marine systems31,32,33. Nutrient enrichment showed contrasting relations: bacterial diversity decreased with phosphorus—aligning with global patterns observed in lakes and streams34—but increased with nitrogen, probably due to the direct dependency of many taxa on nitrogen resources. Negative associations were frequently observed at higher nutrient concentrations, in the order of magnitude of 10 mg l−1 total nitrogen35, while the mean of all bacteria studies analysed here was 2.17 mg l−1 (s.d. = 0.8). Salinity and oxygen depletion showed no clear trends.

Algae, covering both planktonic and benthic algae, showed strong curve–linear relations to salinity and nutrient levels. The negative relationship to salinity was particularly strong, probably driven by osmotic stress19,36, supporting the general accepted conjecture that freshwater species are not directly replaced by brackish water species when salinity increases. Algal richness and evenness were positively associated with nutrient enrichment, particularly nitrogen, reflecting enhanced productivity37. This result contrasts with the general assumption that eutrophication is a prime stressor to phytoplankton biodiversity35—obviously, moderate nutrient input can enable higher alpha-diversity of algae. However, the more frequent occurrence of generalists and competitive species under eutrophic conditions may decline beta- and gamma-diversity because of disappearance of specialists for oligotrophic conditions38. The observed positive relationship may simply reflect higher specimen numbers in eutrophic waters, which increase the likelihood of detecting more species. Other stressor–response relations were weaker, suggesting indirect relations (for example, through another environmental variables) and data insufficiency.

Macrophytes (aquatic bryophytes and vascular plants) showed unique stressor–response patterns. They were positively associated with oxygen and flow cessation, probably benefiting from the stabilization of sediments and reduced force of current39,40. However, they showed negative relationships with salinity and nitrogen enrichment, which might favour a limited number of tolerant and competitive species outcompeting others and thus reducing species number and evenness41,42. These distinct associations highlight the specialized ecological niches occupied by macrophytes in river systems.

Invertebrates exhibited predominantly negative associations with both habitat and water quality stressors, particularly salinity, oxygen depletion, fine sediment accumulation and warming. These patterns probably reflect their sensitivity to habitat degradation and declining water quality18,25,43. Nutrient enrichment was only weakly associated, suggesting that direct nutrient impacts may be less relevant than habitat alterations and acts in an indirect way, for example through temporary oxygen depletion20.

Fish exhibit a mix of positive and negative stressor–response relationships. Negative relations were observed for salinity, oxygen depletion, sediment accumulation and flow cessation, reflecting habitat degradation and metabolic constraints44. Conversely, positive relationships with rising temperatures may reflect the dominance of warm-water species in downstream fish regions, which naturally exhibit a higher species richness compared with the cooler upstream areas; however, other factors such as habitat characteristics shape these patterns45,46. Nutrient enrichment showed minimal patterns and probably influenced fish only indirectly via oxygen depletion, habitat structure or prey availability.

Hypothetical outcome plots (HOPs) (Fig. 3) illustrate associations between taxonomic richness and selected key stressors, chosen on the basis of strength and uncertainty of observed relationships. Invertebrate and fish richness showed contrasting associations to increasing temperature (Fig. 3a,b), with a decline in invertebrate richness and a positive trend for fish richness. These patterns reflect differences in thermal sensitivity and physiological constraints. Invertebrate richness declined with warming, probably reflecting reduced oxygen availability. In contrast, fish richness tended to increase with moderate temperature rises, potentially coinciding with expanding river size naturally positively correlated with fish richness47 seasonal patterns48, as well as increase in exotic species49. Both, invertebrate and fish richness were negatively related to fine sediment accumulation and flow cessation, respectively (Fig. 3c,d), emphasizing the negative association between excessive sedimentation and reduced flow velocity on habitat complexity and potentially on oxygen availability. Fine sediment accumulation has been recognized as a key threat for riverine macroinvertebrates50,51 and fish52, but quantifications of stressor–responses relations remain scarce.

Partial dependence plots (PDPs) (Fig. 4) illustrate the additive relation of two key stressors on taxonomic richness, highlighting how biodiversity related to several environmental stressors. Invertebrate richness as a function of temperature and oxygen depletion revealed that while high oxygen levels promote taxa richness, these benefits are reduced by elevated temperatures (Fig. 4a). Fish richness was consistently lower with higher fine sediment fraction and lower flow velocity (Fig. 4b), two hydromorphological stressors that are known to jointly reduce habitat quality and complexity. These findings reinforce the need for holistic management approaches, as the effectiveness of mitigating a single stressor may depend on the presence or severity of others that account for multistressor conditions rather than addressing stressors in isolation.

Management and research implications

Our results emphasize the importance of management strategies tailored to regional conditions and stressor intensities53. Consistently, all taxa were strongly and negatively associated with salinity. As salinity is strongly correlated with other stressors, such as pesticides54, it may serve as a proxy for broader ecological degradation. Other stressors showed more variable associations. For example, warming was positively associated with the diversity of most organism groups, in particular fish, but negatively with invertebrates. At least in parts, this observation might simply reflect higher species numbers of warmer, downstream river reaches, which is most obvious for fish, while species richness of invertebrates typically declines downstream. These findings highlight the limitations of simplistic biodiversity metrics, such as species richness, which may obscure declines in specialist or functionally important taxa due to the proliferation of generalists. Despite these complexities, several overarching patterns emerged: salinization, oxygen depletion, fine sediment accumulation and flow cessation consistently related negatively with biodiversity, particularly for fish and invertebrates. In contrast, nutrient enrichment had minimal relations to most taxa but was strongly positively associated to algal diversity, although this observation might have been caused by the higher specimen numbers in samples from eutrophic waters potentially leading to reduced beta-diversity38.

Future research should aim to disentangle these relationships, identifying primary drivers to improve mitigation strategies. Addressing the observed variability in stressor–response patterns will require integrating local environmental conditions, species-specific tolerances and multivariable stressor interactions into ecological assessments.

Effective management of rivers must prioritize pollution reduction, sediment budget restoration and improved flow regimes to safeguard biodiversity. Additionally, fostering transparent data sharing and integrative modelling approaches will enhance our ability to refine stressor–response relationships and advance ecological understanding. By building on the findings of this study, future research can drive information-based conservation actions and support the sustainable management of aquatic ecosystems.

Beyond estimating the stressor–response relationships, this synthesis highlights the need for improved ecological data reporting. The available data reflect the research priorities of recent decades rather than the actual relevance of stressors, organism groups, or river types. The dataset is heavily dominated by studies from a few countries—particularly the USA, China and Germany—and macroinvertebrates are substantially better represented than other organism groups. In addition, several emergent stressors, such as contaminants and invasive species, were not considered because of difficulties in parameterization. In addition, small sample sizes and incomplete reporting constrained our ability to account for spatial and temporal autocorrelation, probably contributing to the heterogeneity among stressor–response relationships. Finally, the reliance on summary statistics (for example, means, medians and standard deviations) and the lack of accessible raw datasets constrain the precision of meta-analyses, a cumulative scientific approach, and hinder the detection of ecological patterns relevant to conservation and management. Greater availability of multivariate datasets, coupled with data-sharing practices, would enhance the transferability of findings. The dataset and analytical framework presented here provide a foundation for future assessments, offering an adaptable structure that can be updated using the accompanying code or by incorporating posterior estimates as priors in subsequent analyses. This flexibility supports ongoing monitoring efforts and ensures that findings remain relevant for guiding ecological research and management.

Bayesian approaches offer a promising avenue for synthesizing and integrating diverse data sources while accounting for parameter uncertainties55. Incorporating methods such as Bayesian network meta-analyses56 enables estimation of missing components by leveraging existing models, facilitating more robust predictions of stressor impacts. The compiled data source will act as a continuously improving baseline for the quantification of stressor–response relationships. Expanding predictive modelling capabilities through Bayesian methods can further refine stressor–response assessments, improving management strategies. These models can inform predictive-scenario testing, enabling managers to evaluate alternative stressor reduction strategies and their expected outcomes on biodiversity. Integrating such approaches into conservation planning will enhance our ability to mitigate anthropogenic stressors and strengthen freshwater ecosystem resilience.

Methods

Overview

We systematically identified studies that examined stressor–response relationships under field conditions. For each study, we extracted the data and fitted separate GLMMs to each dataset. The resulting parameter estimates (regression coefficients) from these individual models were then synthesized through a meta-analysis using Bayesian model averaging.

Step 1: Data collection and literature search

We compiled a comprehensive dataset on stressor–response relationships in riverine ecosystems under field conditions through a systematic Web of Science search. We encompassed five key riverine organism groups—bacteria/archaea, algae, macrophytes, invertebrates and fish—and seven major anthropogenic stressors—salinity increase, oxygen depletion, fine sediment enrichment, temperature increase, flow cessation and nitrogen and phosphorus enrichment. To ensure ecological realism, we excluded laboratory-based experiments, restricting our analysis to field studies. This search initially yielded 22,120 articles, which were systematically screened, resulting in 223 retained studies (Supplementary Information (step 1)). We supplemented this dataset with 55 additional studies from the open-access repositories Dryad, GitHub and Zotero, yielding a final dataset of 276 studies22,25,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150,151,152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160,161,162,163,164,165,166,167,168,169,170,171,172,173,174,175,176,177,178,179,180,181,182,183,184,185,186,187,188,189,190,191,192,193,194,195,196,197,198,199,200,201,202,203,204,205,206,207,208,209,210,211,212,213,214,215,216,217,218,219,220,221,222,223,224,225,226,227,228,229,230,231,232,233,234,235,236,237,238,239,240,241,242,243,244,245,246,247,248,249,250,251,252,253,254,255,256,257,258,259,260,261,262,263,264,265,266,267,268,269,270,271,272,273,274,275,276,277,278,279,280,281,282,283,284,285,286,287,288,289,290,291,292,293,294,295,296,297,298,299,300,301,302,303,304,305,306,307,308,309,310,311,312,313,314,315,316,317,318,319,320,321,322,323,324,325,326,327,328,329,330 encompassing 1,332 quantified biota–stressor relationships (Fig. 5).

We extracted data on key response variables, including taxonomic richness and evenness from figures, tables and supplementary datasets, prioritizing the most commonly reported metrics for each organism group. As independent variables, we extracted proxies of stressor intensities (for a full list of proxies compare Supplementary Information (step 1)). We also extracted if the study was based on a temporal or a spatial gradient (Fig. 6 (step 1) and Supplementary Information (step 1)). We refer to the data extracted from an individual study as ‘individual dataset’ in the following.

Step 2: Model fitting and parameter extraction

The purpose of this step was to derive the model parameters and standard errors of the GLMM between each stressor and biotic response for each individual dataset, that is for each stressor–response relationship stemming from a single study. We applied GLMMs to model the response variables as follows. The linear component of the GLMMs was modelled with a log-link (taxonomic richness; count data) or with the logit-link (evenness and coverage; proportional data) (Fig. 6 (step 2)).

To facilitate parameter estimation, all independent variables were log-transformed (natural log), ensuring that model parameters corresponded to elasticity and semi-elasticity coefficients331. Elasticity coefficients, estimated via log-linear models, quantify the percentage change in a response variable per 1% increase in stressor intensity (for example, an elasticity of 0.2 indicates a 0.2% response change). Semi-elasticity coefficients, estimated via logit-linear models, measure the change in the logged odds of the response variable per 1% change in stressor intensity. When approaching zero, they closely approximate elasticity coefficients, enhancing interpretability.

This approach enables three key advantages: (1) the use of general priors across models, (2) comparable interpretation of stressor impacts and (3) the avoidance of self-referential issues and of bias introduced by z-transformations or minimum-maximum transformations, facilitating comparisons across models (Supplementary Information (step 2)).

If studies provided information on sampling dates, seasons or years, or on individual rivers sampled, random effects were applied if they did not lead to convergence issues in the model.

Step 3: Storage of estimated parameters

All the estimated elasticity and semi-elasticity coefficients (regression coefficients and intercepts) for each stressor–response relationship were stored in a database (Fig. 6 (step 3) and Supplementary Fig. 2b (step 3)).

Step 4: A priori bias assessment and quality control

Data extracted from literature might favour certain response categories, for example stronger and ‘significant’ over weaker ‘non-significant’ responses. To assess this potential publication bias, we applied Egger’s test, examining the shift in intercept based on the relationship between the inverse standard error and the ratio of parameter estimates to standard error (Fig. 6 (step 4)). Additionally, we analysed the distribution of z-values to identify systematic patterns indicative of selection bias332. These analyses revealed no clear bias, reinforcing the robustness of our estimates and minimizing the risk of overestimating stressor impacts (Supplementary Information (step 4)).

Step 5: Prior formulation

A key element of our approach was the application of Bayesian model averaging (BMA) that allows for guiding models towards plausible stressor–response relationships based on prior information55. BMA requires the generation of several priors. In the Bayesian framework, posterior probabilities reflect updated priors of stressor–response relations given the likelihood of the data. To implement BMA, we generated four priors for each stressor–response relationship, classifying them into three sets: negative, neutral (unclear) or positive. This allowed us to incorporate directional expectations, such as the anticipated negative impact of salinity on freshwater biota. Details on prior selection are provided in Supplementary Information (step 5).

Step 6: Meta-analysis

Applying the priors generated in step 5, we conducted a meta-analysis with the model parameters for each stressor–response relationship. We conducted a random-effects meta-analysis using BMA (Fig. 6 (step 6)) via R2JAGS. The Markov-chain-Monte-Carlo iterations were set to 30 chains with 3,000 iterations, thinned by 30. Model convergence was ensured by requiring: Rhat <1.01 and effective sample size >3,000. Bias adjustments were deemed unnecessary based on steps 4 and 7 (Supplementary Information (step 6)).

Step 7: Posterior bias check

In addition to the a priori bias assessment (step 4) we conducted posterior bias checks following the meta-analysis (Fig. 6 (step 7)). We used funnel plots, which assessed posterior mean residuals as a function of the inverse of the standard error (1/s.e.). No diagonal patterns were observed, indicating no clear bias in stressor–response estimates (Supplementary Information (step 7)).

Step 8: Posterior sensitivity check

We conducted a sensitivity analysis to evaluate the extent to which the priors influence the posterior estimates. To do this, we compared the posterior results presented in the main text with those from an alternative model using diffuse priors (priors without specific prior information) (Fig. 6 (step 8)). The analysis revealed that our prior assumptions about the stressor–response relationship tend to be more negative than the estimates derived from the data. Although some deviations from zero were observed, the estimated mode (the central tendency) remained stable (Supplementary Information (step 8)).

Step 9: Visualization of stressor–response relationships

We generated several visualizations to enhance interpretability (Fig. 6 (step 9)). Posterior density plots (Fig. 2) illustrate plausible values for log-linear and logit-linear models, highlighting maximum-a-posteriori (MAP) estimates and 90% high-density intervals. HOPs (Fig. 3) visualize selected stressor–response combinations, modelling expected associations across stressor gradients while keeping other variables constant. Each HOP shows regression lines derived from posterior distributions, emphasizing variability. PDPs (Fig. 4) illustrate the marginal effects of two key stressors, aiding management-focused predictions (Supplementary Information (step 9)).

Software and statistical packages

All analyses were performed in R. GLMMs were fitted with the glmmTMB package333 (v.1.1.8) that handles random-effect structures in ecological data. The GAMLSS package334 (v.5.4-20) was used for distributional analyses, while Bayesian modelling was conducted using JAGS (v.4.3.1) via the R2Jags package335. Data visualization was completed with ggplot2336 (v.3.4.4), cowplot337 (v.1.1.3) and bezier338 (v.1.1.2).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Supplementary Data 1 provides details on all the articles and other data sources used in the meta-analysis and on the derived priors. Supplementary Data 2 lists the posterior estimations of all combinations of stressors and organism groups. Both files are available via GitHub at https://github.com/snwikaij/Data and Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16947786 (ref. 339).

Code availability

To support reproducibility, we developed an open-access R package, EcoPostView, enabling users to replicate, extend or visualize our analyses. This package allows custom data integration, alternative priors and posterior density visualization. The code and scripts used in this meta-analysis are available via GitHub at https://github.com/snwikaij/Data and the functions will be provided under the EcoPostView package via GitHub at https://github.com/snwikaij/EcoPostView.

References

Darwall, W. et al. The Alliance for Freshwater Life: a global call to unite efforts for freshwater biodiversity science and conservation. Aquat. Conserv. 28, 1015–1022 (2018).

Reid, A. J. et al. Emerging threats and persistent conservation challenges for freshwater biodiversity. Biol. Rev. 94, 849–873 (2019).

Halbach, K. et al. Small streams–large concentrations? Pesticide monitoring in small agricultural streams in Germany during dry weather and rainfall. Water Res. 203, 117535 (2021).

Kontchou, J. A. et al. Pollutant load and ecotoxicological effects of sediment from stormwater retention basins to receiving surface water on Lumbriculus variegatus. Sci. Total Environ. 859, 160185 (2023).

Markert, N., Schürings, C. & Feld, C. K. Water Framework Directive micropollutant monitoring mirrors catchment land use: importance of agricultural and urban sources revealed. Sci. Total Environ. 917, 170583 (2024).

King, A. J., Townsend, S. A., Douglas, M. M. & Kennard, M. J. Implications of water extraction on the low-flow hydrology and ecology of tropical savannah rivers: an appraisal for northern Australia. Freshw. Sci. 34, 741–758 (2015).

Broadley, A., Stewart-Koster, B., Kenyon, R. A., Burford, M. A. & Brown, C. J. Impact of water development on river flows and the catch of a commercial marine fishery. Ecosphere 11, e03194 (2020).

Geist, J. & Hawkins, S. J. Habitat recovery and restoration in aquatic ecosystems: current progress and future challenges. Aquat. Conserv. 26, 942–962 (2016).

Rivaes, R. P. et al. River ecosystem endangerment from climate change-driven regulated flow regimes. Sci. Total Environ. 818, 151857 (2022).

Thompson, J. R., Gosling, S. N., Zaherpour, J. & Laizé, C. L. R. Increasing risk of ecological change to major rivers of the world with global warming. Earth’s Future 9, e2021EF002048 (2021).

Lemm, J. U. et al. Multiple stressors determine river ecological status at the European scale: towards an integrated understanding of river status deterioration. Glob. Change Biol. 27, 1962–1975 (2021).

Brauns, M. et al. A global synthesis of human impacts on the multifunctionality of streams and rivers. Glob. Change Biol. 28, 4783–4793 (2022).

Bănăduc, D. et al. Multi-interacting natural and anthropogenic stressors on freshwater ecosystems: their current status and future prospects for 21st century. Water 16, 1483 (2024).

Jackson, M. C., Loewen, C. J. G., Vinebrooke, R. D. & Chimimba, C. T. Net effects of multiple stressors in freshwater ecosystems: a meta-analysis. Glob. Change Biol. 22, 180–189 (2016).

Orr, J. A. et al. Studying interactions among anthropogenic stressors in freshwater ecosystems: a systematic review of 2396 multiple-stressor experiments. Ecol. Lett. 27, e14463 (2024).

Keck, F. et al. The global human impact on biodiversity. Nature 641, 395–400 (2025).

Frakes, J. I., Birrell, J. H., Shah, A. A. & Woods, H. A. Flow increases tolerance of heat and hypoxia of an aquatic insect. Biol. Lett. 17, rsbl.2021.0004, 20210004 (2021).

Jonsson, B. & Jonsson, N. A review of the likely effects of climate change on anadromous Atlantic salmon Salmo salar and brown trout Salmo trutta, with particular reference to water temperature and flow. J. Fish. Biol. 75, 2381–2447 (2009).

Remane, A. & Schlieper, C. The Biology of Brackish Waters (E. Schweizerbart’sche Verlag, 1972).

Hering, D. et al. Assessment of European streams with diatoms, macrophytes, macroinvertebrates and fish: a comparative metric-based analysis of organism response to stress. Freshw. Biol. 51, 1757–1785 (2006).

Haase, P., Hering, D., Jähnig, S. C., Lorenz, A. W. & Sundermann, A. The impact of hydromorphological restoration on river ecological status: a comparison of fish, benthic invertebrates, and macrophytes. Hydrobiologia 704, 475–488 (2013).

Kaijser, W., Hering, D. & Lorenz, A. W. Reach hydromorphology: a crucial environmental variable for the occurrence of riverine macrophytes. Hydrobiologia 849, 4273–4285 (2022).

Jordaan, K. & Bezuidenhout, C. The impact of physico-chemical water quality parameters on bacterial diversity in the Vaal River, South Africa. Water SA 39, 385–396 (2013).

Manna, R. K. et al. Spatio-temporal changes of hydro-chemical parameters in the estuarine part of the River Ganges under altered hydrological regime and its impact on biotic communities. Aquat. Ecosyst. Health Manag. 16, 433–444 (2013).

Croijmans, L., De Jong, J. F. & Prins, H. H. T. Oxygen is a better predictor of macroinvertebrate richness than temperature—a systematic review. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 023002 (2021).

Dewson, Z. S., James, A. B. W. & Death, R. G. A review of the consequences of decreased flow for instream habitat and macroinvertebrates. J. N. Am. Benthol. Soc. 26, 401–415 (2007).

Rolls, R. J., Leigh, C. & Sheldon, F. Mechanistic effects of low-flow hydrology on riverine ecosystems: ecological principles and consequences of alteration. Freshw. Sci. 31, 1163–1186 (2012).

Heino, J., Tolkkinen, M., Pirttilä, A. M., Aisala, H. & Mykrä, H. Microbial diversity and community–environment relationships in boreal streams. J. Biogeogr. 41, 2234–2244 (2014).

Thompson, L. R. et al. A communal catalogue reveals Earth’s multiscale microbial diversity. Nature 551, 457–463 (2017).

Wang, J. et al. Regional and global elevational patterns of microbial species richness and evenness. Ecography 40, 393–402 (2017).

Fuhrman, J. A. et al. A latitudinal diversity gradient in planktonic marine bacteria. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 7774–7778 (2008).

Ibarbalz, F. M. et al. Global trends in marine plankton diversity across kingdoms of life. Cell 179, 1084–1097 (2019).

Pommier, T. et al. Global patterns of diversity and community structure in marine bacterioplankton. Mol. Ecol. 16, 867–880 (2007).

Azevedo, L. B. et al. Species richness–phosphorus relationships for lakes and streams worldwide. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 22, 1304–1314 (2013).

Poikane, S. et al. Deriving nutrient criteria to support ʽgoodʼ ecological status in European lakes: an empirically based approach to linking ecology and management. Sci. Total Environ. 650, 2074–2084 (2019).

Bisson, M. A. & Bartholomew, D. Osmoregulation or turgor regulation in Chara?. Plant Physiol. 74, 252–255 (1984).

Stomp, M., Huisman, J., Mittelbach, G. G., Litchman, E. & Klausmeier, C. A. Large-scale biodiversity patterns in freshwater phytoplankton. Ecology 92, 2096–2107 (2011).

Li, Y. et al. Eutrophication decrease compositional dissimilarity in freshwater plankton communities. Sci. Total Environ. 821, 153434 (2022).

Biggs, B. J. F. Hydraulic habitat of plants in streams. Regul. Rivers Res. Mgmt 12, 131–144 (1996).

Chambers, P. A., Prepas, E. E., Hamilton, H. R. & Bothwell, M. L. Current velocity and its effect on aquatic macrophytes in flowing waters. Ecol. Appl. 1, 249–257 (1991).

Haury, J. et al. A new method to assess water trophy and organic pollution—the macrophyte biological index for rivers (IBMR): its application to different types of river and pollution. Hydrobiologia 570, 153–158 (2006).

Verhofstad, M. J. J. M. et al. Mass development of monospecific submerged macrophyte vegetation after the restoration of shallow lakes: roles of light, sediment nutrient levels, and propagule density. Aquat. Bot. 141, 29–38 (2017).

Bartels, A., Berninger, U. G., Hohenberger, F., Wickham, S. & Petermann, J. S. Littoral macroinvertebrate communities of alpine lakes along an elevational gradient (Hohe Tauern National Park, Austria). PLoS ONE 16, e0255619 (2021).

Nikinmaa, M. & Rees, B. B. Oxygen-dependent gene expression in fishes. Am. J. Physiol. 288, R1079–R1090 (2005).

Bonacina, L., Fasano, F., Mezzanotte, V. & Fornaroli, R. Effects of water temperature on freshwater macroinvertebrates: a systematic review. Biol. Rev. 98, 191–221 (2023).

Smith, G. R., Badgley, C., Eiting, T. P. & Larson, P. S. Species diversity gradients in relation to geological history in North American freshwater fishes. Evol. Ecol. Res. 12, 693–726 (2010).

Ngor, P. B. et al. Predicting fish species richness and abundance in the Lower Mekong Basin. Front. Ecol. Evol. 11, 1131142 (2023).

Duarte, C., Antão, L. H., Magurran, A. E. & De Deus, C. P. Shifts in fish community composition and structure linked to seasonality in a tropical river. Freshw. Biol. 67, 1789–1800 (2022).

Leclerc, C. et al. Climate impacts on lake food-webs are mediated by biological invasions. Glob. Change Biol. 31, e70144 (2025).

Gieswein, A., Hering, D. & Lorenz, A. W. Development and validation of a macroinvertebrate-based biomonitoring tool to assess fine sediment impact in small mountain streams. Sci. Total Environ. 652, 1290–1301 (2019).

Jones, J. I., Collins, A. L., Naden, P. S. & Sear, D. A. The relationship between fine sediment and macrophytes in rivers: fine sediment and macrophytes. River Res. Appl. 28, 1006–1018 (2012).

Descloux, S., Datry, T. & Usseglio-Polatera, P. Trait-based structure of invertebrates along a gradient of sediment colmation: benthos versus hyporheos responses. Sci. Total Environ. 466–467, 265–276 (2014).

Birk, S. et al. Impacts of multiple stressors on freshwater biota across spatial scales and ecosystems. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 4, 1060–1068 (2020).

Berger, E. et al. Water quality variables and pollution sources shaping stream macroinvertebrate communities. Sci. Total Environ. 587–588, 1–10 (2017).

Hinne, M., Gronau, Q. F., Van Den Bergh, D. & Wagenmakers, E.-J. A conceptual introduction to Bayesian model averaging. Adv. Methods Pract. Psychol. Sci. 3, 200–215 (2020).

Hu, D., O’Connor, A. M., Wang, C., Sargeant, J. M. & Winder, C. B. How to conduct a Bayesian network meta-analysis. Front. Vet. Sci. 7, 271 (2020).

Shen, C. et al. Identifying microbial distribution drivers of archaeal community in sediments from a black-odorous urban river—a case study of the Zhang river basin. Water 13, 1545 (2021).

Munyika, S., Kongo, V. & Kimwaga, R. River health assessment using macroinvertebrates and water quality parameters: a case of the Orange River in Namibia. Phys. Chem. Earth 76–78, 140–148 (2014).

Eitzmann, J. L. & Paukert, C. P. Longitudinal differences in habitat complexity and fish assemblage structure of a Great Plains river. Am. Midl. Nat. 163, 14–32 (2010).

Ko, N. T., Suter, P., Conallin, J., Rutten, M. & Bogaard, T. Aquatic macroinvertebrate community changes downstream of the hydropower generating dams in Myanmar—potential negative impacts from increased power generation. Front. Water 2, 573543 (2020).

Dang, H. et al. Diversity, abundance, and spatial distribution of sediment ammonia-oxidizing betaproteobacteria in response to environmental gradients and coastal eutrophication in Jiaozhou Bay, China. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76, 4691–4702 (2010).

Wojtal, A. Z. & Sobczyk, Ł The influence of substrates and physicochemical factors on the composition of diatom assemblages in karst springs and their applicability in water-quality assessment. Hydrobiologia 695, 97–108 (2012).

Xia, Y. et al. Heavy metal distribution and microbial diversity of the surrounding soil and tailings of two Cu mines in China. Water Air Soil Pollut. 234, 241 (2023).

Penczak, T. & Agostinho, A. A. Głowacki, Ł. & Gomes, L. C. The effect of artificial increases in water conductivity on the efficiency of electric fishing in tropical streams (Paraná, Brazil). Hydrobiologia 350, 189–202 (1997).

Von Fumetti, S., Dmitrović, D. & Pešić, V. The influence of flooding and river connectivity on macroinvertebrate assemblages in rheocrene springs along a third-order river. Fund. Appl. Limnol. 190, 251–263 (2017).

Shokri, M., Rossaro, B. & Rahmani, H. Response of macroinvertebrate communities to anthropogenic pressures in Tajan River (Iran). Biologia 69, 1395–1409 (2014).

Xu, Z.-H., Yin, X.-A., Zhang, C. & Yang, Z.-F. Piecewise model for species–discharge relationships in rivers. Ecol. Eng. 96, 208–213 (2016).

Watt, D. A. Estuaries of contrasting trophic status in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 47, 209–216 (1998).

Short, T. M., Black, J. A. & Birge, W. J. Ecology of a saline stream: community responses to spatial gradients of environmental conditions. Hydrobiologia 226, 167–178 (1991).

Bai, Y., Qi, W., Liang, J. & Qu, J. Using high-throughput sequencing to assess the impacts of treated and untreated wastewater discharge on prokaryotic communities in an urban river. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 98, 1841–1851 (2014).

He, H. et al. Determinants of bacterioplankton structures in the typically turbid Weihe River and its clear tributaries from the northern foot of the Qinling Mountains. Ecol. Indic. 121, 107168 (2021).

Kimmel, W. G. & Argent, D. G. Stream fish community responses to a gradient of specific conductance. Water Air Soil Pollut. 206, 49–56 (2010).

Arbeláez, F., Duivenvoorden, J. F. & Maldonado-Ocampo, J. A. Geological differentiation explains diversity and composition of fish communities in upland streams in the southern Amazon of Colombia. J. Trop. Ecol. 24, 505–515 (2008).

Živić, I. et al. Global warming effects on benthic macroinvertebrates: a model case study from a small geothermal stream. Hydrobiologia 732, 147–159 (2014).

Krebs, J. M., McIvor, C. C. & Bell, S. S. Nekton community structure varies in response to coastal urbanization near mangrove tidal tributaries. Estuaries Coasts 37, 815–831 (2014).

Helms, B. et al. Development of ecogeomorphological (EGM) stream design and assessment tools for the piedmont of Alabama, USA. Water 8, 161 (2016).

Cabrini, R., Canobbio, S., Sartori, L., Fornaroli, R. & Mezzanotte, V. Leaf packs in impaired streams: the influence of leaf type and environmental gradients on breakdown rate and invertebrate assemblage composition. Water Air Soil Pollut. 224, 1697 (2013).

Collier, K. J. & Smith, B. J. Distinctive invertebrate assemblages in rockface seepages enhance lotic biodiversity in northern New Zealand. Biodivers. Conserv 15, 3591–3616 (2006).

Riis, T. & Biggs, B. J. F. Hydrologic and hydraulic control of macrophyte establishment and performance in streams. Limnol. Oceanogr. 48, 1488–1497 (2003).

Varadinova, E., Sakelarieva, L., Park, J., Ivanov, M. & Tyufekchieva, V. Characterisation of macroinvertebrate communities in Maritsa River (South Bulgaria)—relation to different environmental factors and ecological status assessment. Diversity 14, 833 (2022).

Tupinambás, T. H., Callisto, M. & Santos, G. B. Benthic macroinvertebrate assemblages structure in two headwater streams, south-eastern Brazil. Rev. Bras. Zool. 24, 887–897 (2007).

Grubaugh, J., Wallace, B. & Houston, E. Production of benthic macroinvertebrate communities along a southern Appalachian river continuum. Freshw. Biol. 37, 581–596 (1997).

Coghlan, S. M. & Ringler, N. H. Survival and bioenergetic responses of juvenile Atlantic salmon along a perturbation gradient in a natural stream. Ecol. Freshw. Fish. 14, 111–124 (2005).

Dias, R. M., De Oliveira, A. G., Baumgartner, M. T., Angulo-Valencia, M. A. & Agostinho, A. A. Functional erosion and trait loss in fish assemblages from Neotropical reservoirs: the man beyond the environment. Fish Fish. 22, 377–390 (2021).

França, S., Costa, M. J. & Cabral, H. N. Inter- and intra-estuarine fish assemblage variability patterns along the Portuguese coast. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 91, 262–271 (2011).

Eppehimer, D. E., Hamdhani, H., Hollien, K. D. & Bogan, M. T. Evaluating the potential of treated effluent as novel habitats for aquatic invertebrates in arid regions. Hydrobiologia 847, 3381–3396 (2020).

Kefford, B. J., Nichols, S. J. & Duncan, R. P. The cumulative impacts of anthropogenic stressors vary markedly along environmental gradients. Glob. Change Biol. 29, 590–602 (2023).

Aguinaga, O. E., McMahon, A., White, K. N., Dean, A. P. & Pittman, J. K. Microbial community shifts in response to acid mine drainage pollution within a natural wetland ecosystem. Front. Microbiol. 9, 1445 (2018).

Kong, X. et al. Ecological improvement by restoration on the Jialu River: water quality, species richness and distribution. Mar. Freshw. Res. 71, 1602 (2020).

Budi Prakoso, S., Miyake, Y., Ueda, W. & Suryatmojo, H. Impact of land use on water quality and invertebrate assemblages in Indonesian streams. Limnologica 101, 126082 (2023).

Paulson, E. L. & Martin, A. P. Inferences of environmental and biotic effects on patterns of eukaryotic alpha and beta diversity for the spring systems of Ash Meadows, Nevada. Oecologia 191, 931–944 (2019).

Snyder, E. B., Robinson, C. T., Minshall, G. W. & Rushforth, S. R. Regional patterns in periphyton accrual and diatom assemblage structure in a heterogeneous nutrient landscape. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 59, 564–577 (2002).

Bailly, D., Cassemiro, F. A. S., Agostinho, C. S., Marques, E. E. & Agostinho, A. A. The metabolic theory of ecology convincingly explains the latitudinal diversity gradient of Neotropical freshwater fish. Ecology 95, 553–562 (2014).

Bournaud, M., Cellot, B., Richoux, P. & Berrahou, A. Macroinvertebrate community structure and environmental characteristics along a large river: congruity of patterns for identification to species or family. J. North Am. Benthol. Soc. 15, 232–253 (1996).

Savić, A., Dmitrović, D. & Pešić, V. Ephemeroptera, Plecoptera, and Trichoptera assemblages of karst springs in relation to some environmental factors: a case study in central Bosnia and Herzegovina. Turk. J. Zool. 41, 119–129 (2017).

Wang, H. et al. Functional bacteria as potential indicators of water quality in Three Gorges Reservoir, China. Environ. Monit. Assess. 163, 607–617 (2010).

Iqbal, H. H. et al. Hydrological and ichthyological impact assessment of Rasul Barrage, River Jhelum,Pakistan. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 26, 107–114 (2017).

Kennen, J. G., Riskin, M. L. & Charles, E. G. Effects of streamflow reductions on aquatic macroinvertebrates: linking groundwater withdrawals and assemblage response in southern New Jersey streams, USA. Hydrol. Sci. J. 59, 545–561 (2014).

Wedderburn, S. D., Whiterod, N. S., Barnes, T. C. & Shiel, R. J. Ecological aspects related to reintroductions to avert the extirpation of a freshwater fish from a large floodplain river. Aquat. Ecol. 54, 281–294 (2020).

Menni, R. C. et al. Fish fauna and environments of the Pilcomayo-Paraguay basins in Formosa, Argentina. Hydrobiologia 245, 129–146 (1992).

Ceschin, S., Minciardi, M. R., Spada, C. D. & Abati, S. Bryophytes of Alpine and Apennine mountain streams: floristic features and ecological notes. Cryptogam. Bryologie 36, 267–283 (2015).

Gomes, P. et al. Algae in acid mine drainage and relationships with pollutants in a degraded mining ecosystem. Minerals 11, 110 (2021).

Matern, S. A., Moyle, P. B. & Pierce, L. C. Native and alien fishes in a california estuarine marsh: twenty-one years of changing assemblages. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 131, 797–816 (2002).

Zamora-Muñoz, C. & Alba-Tercedor, J. Bioassessment of organically polluted Spanish rivers, using a biotic index and multivariate methods. J. North Am. Benthol. Soc. 15, 332–352 (1996).

Abed, R. M. M., Palinska, K. A. & Köster, J. Characterization of microbial mats from a desert wadi ecosystem in the Sultanate of Oman. Geomicrobiol. J. 35, 601–611 (2018).

Rozanov, A. S., Bryanskaya, A. V., Ivanisenko, T. V., Malup, T. K. & Peltek, S. E. Biodiversity of the microbial mat of the Garga hot spring. BMC Evol. Biol. 17, 254 (2017).

Spitale, D., Leira, M., Angeli, N. & Cantonati, M. Environmental classification of springs of the Italian Alps and its consistency across multiple taxonomic groups. Freshw. Sci. 31, 563–574 (2012).

Khuram, I., Ahmad, N., Solak, C. N. & Barinova, S. Assessment of water quality by bioindication of algae and cyanobacteria in the Peshawar Valley, Pakistan. Turk. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 22, TRJFAS19805 (2021).

Rodrigues, S., Xavier, B., Nogueira, S. & Antunes, S. C. Intermittent rivers as a challenge for freshwater ecosystems quality evaluation: a study case in the Ribeira de Silveirinhos. Port. Water 15, 17 (2022).

Kreiling, A.-K., Govoni, D. P., Pálsson, S., Ólafsson, J. S. & Kristjánsson, B. K. Invertebrate communities in springs across a gradient in thermal regimes. PLoS ONE 17, e0264501 (2022).

Kupiec, J. M., Staniszewski, R. & Jusik, S. Assessment of the impact of land use in an agricultural catchment area on water quality of lowland rivers. PeerJ 9, e10564 (2021).

Lebepe, J., Khumalo, N., Mnguni, A., Pillay, S. & Mdluli, S. Macroinvertebrate assemblages along the longitudinal gradient of an urban palmiet river in Durban, South Africa. Biology 11, 705 (2022).

Majdi, N. et al. Diversity and distribution of benthic invertebrates dwelling rivers of the Kruger National Park, South Africa. Koedoe https://doi.org/10.4102/koedoe.v64i1.1702 (2022).

Wu, N. C. et al. Temporal impacts of a small hydropower plant on benthic algal community. Fund. Appl. Limnol. 177, 257–266 (2010).

Nouri, A., Soumaya, H., Lahcen, C. & Abdelmajid, H. Macrophytes as a tool for assessing the trophic status of a river: a case study of the upper Oum Er Rbia Basin (Morocco). Oceanol. Hydrobiol. Stud. 50, 77–86 (2021).

Vinson, D. K. & Rushforth, S. R. Diatom species composition along a thermal gradient in the Portneuf River, Idaho, USA. Hydrobiologia 185, 41–54 (1989).

Zampella, R. A. & Bunnell, J. F. Use of reference-site fish assemblages to assess aquatic degradation in pinelands streams. Ecol. Appl. 8, 645–658 (1998).

Rasool, A. et al. Microbial diversity and community structure in alpine stream soil. Geomicrobiol. J. 38, 210–219 (2021).

Chowdhury, M. S. N., Hossain, M. S., Das, N. G. & Barua, P. Environmental variables and fisheries diversity of the Naaf River Estuary, Bangladesh. J. Coast Conserv 15, 163–180 (2011).

Molinero, J. et al. The Teaone River: a snapshot of a tropical river from the coastal region of Ecuador. Limnetica 38, 587–605 (2019).

Addo-Bediako, A. Spatial distribution patterns of benthic macroinvertebrate functional feeding groups in two rivers of the olifants river system, South Africa. J. Freshw. Ecol. 36, 97–109 (2021).

Milner, A. M., Taylor, R. C. & Winterbourn, M. J. Longitudinal distribution of macroinvertebrates in two glacier-fed New Zealand rivers. Freshw. Biol. 46, 1765–1775 (2001).

Menció, A. & Boix, D. Response of macroinvertebrate communities to hydrological and hydrochemical alterations in Mediterranean streams. J. Hydrol. 566, 566–580 (2018).

Liasko, R. et al. Influence of environmental parameters on growth pattern and population structure of Carassius auratus gibelio in Eastern Ukraine. Hydrobiologia 658, 317–328 (2011).

Collier, K. J. Environmental factors affecting the taxonomic composition of aquatic macroinvertebrate communities in lowland waterways of Northland, New Zealand. NZ J. Mar. Freshw. Res. 29, 453–465 (1995).

Cornacchia, L. et al. Self-organization of river vegetation leads to emergent buffering of river flows and water levels. Proc. R. Soc. B. 287, 20201147 (2020).

Kaestli, M., Munksgaard, N., Gibb, K. & Davis, J. Microbial diversity and distribution differ between water column and biofilm assemblages in arid-land waterbodies. Freshw. Sci. 38, 869–882 (2019).

Ellison, C. A., Skinner, Q. D. & Hicks, L. S. Assessment of best-management practice effects on rangeland stream water quality using multivariate statistical techniques. Rangel. Ecol. Manag. 62, 371–386 (2009).

Kokeš, J. River channel habitat diversity (RCHD) and macroinvertebrate community. Biologia 66, 328–334 (2011).

Suárez, M. L. et al. Functional response of aquatic invertebrate communities along two natural stress gradients (water salinity and flow intermittence) in Mediterranean streams. Aquat. Sci. 79, 1–12 (2017).

Perlatti, F. et al. Copper release from waste rocks in an abandoned mine (NE, Brazil) and its impacts on ecosystem environmental quality. Chemosphere 262, 127843 (2021).

Veselá, J. Spatial heterogeneity and ecology of algal communities in an ephemeral sandstone stream in the Bohemian Switzerland National Park, Czech Republic. Nova Hedwigia 88, 531–547 (2009).

Aguiar, A. C. F., Gücker, B., Brauns, M., Hille, S. & Boëchat, I. G. Benthic invertebrate density, biomass, and instantaneous secondary production along a fifth-order human-impacted tropical river. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res 22, 9864–9876 (2015).

Niyogi, D. K., Koren, M., Arbuckle, C. J. & Townsend, C. R. Longitudinal changes in biota along four New Zealand streams: declines and improvements in stream health related to land use. NZ J. Mar. Freshw. Res. 41, 63–75 (2007).

Jonsson, M. et al. Land use influences macroinvertebrate community composition in boreal headwaters through altered stream conditions. Ambio 46, 311–323 (2017).

Smolar-Žvanut, N. & Mikoš, M. The impact of flow regulation by hydropower dams on the periphyton community in the Soča River, Slovenia. Hydrol. Sci. J. 59, 1032–1045 (2014).

Libório, R. A. & Tanaka, M. O. Does environmental disturbance also influence within-stream beta diversity of macroinvertebrate assemblages in tropical streams?. Stud. Neotrop. Fauna Environ. 51, 206–214 (2016).

Young, R. G., Huryn, A. D. & Townsend, C. R. Effects of agricultural development on processing of tussock leaf litter in high country New Zealand streams. Freshw. Biol. 32, 413–427 (1994).

Pool, J. R., Kruse, N. A. & Vis, M. L. Assessment of mine drainage remediated streams using diatom assemblages and biofilm enzyme activities. Hydrobiologia 709, 101–116 (2013).

Dirisu, A.-R. & El Surtasi, E. I. Microhabitat associated macrofauna of lotic and lentic systems in the Agbede wetlands, southern Nigeria. Trop. Ecol. 64, 543–557 (2023).

Füreder, L. & Niedrist, G. H. Glacial stream ecology: structural and functional assets. Water 12, 376 (2020).

Leland, H. V. & Porter, S. D. Distribution of benthic algae in the upper Illinois River basin in relation to geology and land use. Freshw. Biol. 44, 279–301 (2000).

Datry, T., Scarsbrook, M., Larned, S. & Fenwick, G. Lateral and longitudinal patterns within the stygoscape of an alluvial river corridor. Fund. Appl. Limnol. 171, 335–347 (2008).

Thiébaut, G. Aquatic macrophyte approach to assess the impact of disturbances on the diversity of the ecosystem and on river quality. Int. Rev. Hydrobiol. 91, 483–497 (2006).

Dudgeon, D. The influence of riparian vegetation on macroinvertebrate community structure and functional organization in six new Guinea streams. Hydrobiologia 294, 65–85 (1994).

Blaen, P. J., Brown, L. E., Hannah, D. M. & Milner, A. M. Environmental drivers of macroinvertebrate communities in high Arctic rivers (Svalbard). Freshw. Biol. 59, 378–391 (2014).

Magagula, C. N., Mansuetus, A. B. & Tetteh, J. O. Ecological health of the Usuthu and Mbuluzi rivers in Swaziland based onselected biological indicators. Afr. J. Aquat. Sci. 35, 283–289 (2010).

Fozia et al. Community dynamics and activity of nirS-harboring denitrifiers in sediments of the Indus River Estuary. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 153, 110971 (2020).

Clarke, K. D. & Scruton, D. A. The benthic community of stream riffles in Newfoundland, Canada and its relationship to selected physical and chemical parameters. J. Freshw. Ecol. 12, 113–121 (1997).

Oeding, S. & Taffs, K. H. Are diatoms a reliable and valuable bio-indicator to assess sub-tropical river ecosystem health?. Hydrobiologia 758, 151–169 (2015).

Schoen, J., Merten, E. & Wellnitz, T. Current velocity as a factor in determining macroinvertebrate assemblages on wood surfaces. J. Freshw. Ecol. 28, 271–275 (2013).

Miller, S. W., Wooster, D. & Li, J. Resistance and resilience of macroinvertebrates to irrigation water withdrawals. Freshw. Biol. 52, 2494–2510 (2007).

Danet, A., Mouchet, M., Bonnaffé, W., Thébault, E. & Fontaine, C. Species richness and food-web structure jointly drive community biomass and its temporal stability in fish communities. Ecol. Lett. 24, 2364–2377 (2021).

Miserendino, M. L. Macroinvertebrate assemblages in Andean Patagonian rivers and streams: environmental relationships. Hydrobiologia 444, 147–158 (2001).

Canak-Atlagic, J. et al. Assessment of the impact of copper mining and related industrial activities on aquatic macroinvertebrate communities of the Pek River (Serbia). Arch. Biol. Sci. 73, 291–301 (2021).

Bonacina, L., Fornaroli, R., Mezzanotte, V. & Marazzi, F. Temporal patterns of stream biofilm in a mountain catchment: one-year monthly samplings across streams of the Orobic Alps (Northern Italy). Hydrobiologia 851, 2081–2097 (2024).

Wang, H., Chen, Y., Liu, Z. & Zhu, D. Effects of the “run-of-river” hydro scheme on macroinvertebrate communities and habitat conditions in a mountain river of northeastern China. Water 8, 31 (2016).

Brown, L. R., May, J. T. & Hunsaker, C. T. Species composition and habitat associations of benthic algal assemblages in headwater streams of the Sierra Nevada, California. West. North Am. Nat. 68, 194–209 (2008).

Wang, S.-Y., Sudduth, E. B., Wallenstein, M. D., Wright, J. P. & Bernhardt, E. S. Watershed urbanization alters the composition and function of stream bacterial communities. PLoS ONE 6, e22972 (2011).

Woodcock, T. S. & Huryn, A. D. The response of macroinvertebrate production to a pollution gradient in a headwater stream. Freshw. Biol. 52, 177–196 (2007).

Robinson, C. T., Thompson, C. & Freestone, M. Ecosystem development of streams lengthened by rapid glacial recession. Fund. Appl. Limnol. 185, 235–246 (2014).

Dorava, J. M. & Milner, A. M. RESEARCH: Effects of recent volcanic eruptions on aquatic habitat in the Drift River, Alaska, USA: implications at other Cook inlet region volcanoes. Environ. Manag. 23, 217–230 (1999).

Koryak, M., Stafford, L. J., Reilly, R. J., Hoskin, R. H. & Haberman, M. H. The impact of airport deicing runoff on water quality and aquatic life in a Pennsylvania stream. J. Freshw. Ecol. 13, 287–298 (1998).

Ding, C. et al. Fish assemblage responses to a low-head dam removal in the Lancang River. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 29, 26–36 (2019).

Pacioglu, O., Duţu, F., Pavel, A. B. & Tiron Duţu, L. The influence of hydrology and sediment grain-size on the spatial distribution of macroinvertebrate communities in two submerged dunes from the Danube Delta (Romania). Limnetica 41, 85–100 (2022).

Bergey, E. A., Matthews, W. J. & Fry, J. E. Springs in time: fish fauna and habitat changes in springs over a 20-year interval. Aquat. Conserv. 18, 829–838 (2008).

Prommi, T. & Payakka, A. Aquatic insect biodiversity and water quality parameters of streams in northern Thailand. Sains Malays. 44, 707–717 (2015).

Weitere, M. et al. Disentangling multiple chemical and non-chemical stressors in a lotic ecosystem using a longitudinal approach. Sci. Total Environ. 769, 144324 (2021).

Banks, L. K., Lavoie, I., Robinson, C. E., Roy, J. W. & Yates, A. G. Effects of groundwater inputs on algal assemblages and cellulose decomposition differ based on habitat type in an agricultural stream. Hydrobiologia 850, 3517–3537 (2023).

Mamun, M. & An, K.-G. Key factors determining water quality, fish community dynamics, and the ecological health in an Asian temperate lotic system. Ecol. Inform. 72, 101890 (2022).

McGarvey, D. J. & Terra, B. D. F. Using river discharge to model and deconstruct the latitudinal diversity gradient for fishes of the Western Hemisphere. J. Biogeogr. 43, 1436–1449 (2016).

Lourenço, J. et al. Non-interactive effects drive multiple stressor impacts on the taxonomic and functional diversity of Atlantic stream macroinvertebrates. Environ. Res. 229, 115965 (2023).

Bungabong, R. W. M., Hadwen, W. L. & Padilla, L. V. Critical evaluation of the hydrological, biological and sociological impacts of the implementation of flood control check dams in the Upper Marikina River Basin Protected Landscape, Philippines. Int. J. River Basin Manag. 21, 357–373 (2023).

Zhang, W. et al. Bacterial communities along a 4,500-meter elevation gradient in the sediment of the Yangtze River: what are the driving factors?. Desalin. Water Treat. 177, 109–130 (2020).

Heino, J. et al. Defining macroinvertebrate assemblage types of headwater streams: implications for bioassessment and conservation. Ecol. Appl. 13, 842–852 (2003).

Yang, J. et al. Effects of phytoplankton community and interaction between environmental variables on nitrogen uptake and transformations in an urban river. J. Ocean. Limnol. 40, 1012–1026 (2022).

Benjamin, J. M., Abuya, D., Omollo, B. & Merimba, C. Longitudinal patterns of abundance, diversity and functional feeding guilds of benthic communities in East African tropical high-altitude streams. Afr. J. Ecol. 61, 781–793 (2023).

Arranz, I., Grenouillet, G. & Cucherousset, J. Biological invasions and eutrophication reshape the spatial patterns of stream fish size spectra in France. Divers. Distrib. 29, 590–597 (2023).

Theodoropoulos, C. & Karaouzas, I. Climate change and the future of Mediterranean freshwater macroinvertebrates: a model-based assessment. Hydrobiologia 848, 5033–5050 (2021).

Ouyang, Z., Qian, S. S., Becker, R. & Chen, J. The effects of nutrients on stream invertebrates: a regional estimation by generalized propensity score. Ecol. Process 7, 21 (2018).

Shuai, F., Li, X., Chen, F., Li, Y. & Lek, S. Spatial patterns of fish assemblages in the Pearl River, China: environmental correlates. Fund. Appl. Limnol. 189, 329–340 (2017).

Murphy, P. M. & Edwards, R. W. The spatial distribution of the freshwater macroinvertebrate fauna of the River Ely, South Wales, in relation to pollutional discharges. Environ. Pollut. A 29, 111–124 (1982).

Beamish, F. W. H., Beamish, R. B. & Lim, S. L.-H. Fish assemblages and habitat in a Malaysian blackwater peat swamp. Environ. Biol. Fishes 68, 1–13 (2003).

Mebane, C. A. Testing bioassessment metrics: macroinvertebrate, sculpin, and salmonid responses to stream habitat, sediment, and metals. Environ. Monit. Assess. 67, 293–322 (2001).

Brown, L. R. & May, J. T. Aquatic vertebrate assemblages of the upper clear creek watershed California. West. North Am. Nat. 67, 439–451 (2007).

Fernández-Aláez, C., De Soto, J., Fernández-Aláez, M. & García-Criado, F. Spatial structure of the caddisfly (Insecta, Trichoptera) communities in a river basin in NW Spain affected by coal mining. Hydrobiologia 487, 193–205 (2002).

Sun, W. et al. Diversity of the sediment microbial community in the Aha watershed (Southwest China) in response to acid mine drainage pollution gradients. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 81, 4874–4884 (2015).

Á Lvarez, M. & Pardo, I. Do temporary streams of Mediterranean islands have a distinct macroinvertebrate community? The case of Majorca. Fund. Appl. Limnol. 168, 55–70 (2007).

Viza, A., Burgazzi, G., Menéndez, M., Schäfer, R. B. & Muñoz, I. A comprehensive spatial analysis of invertebrate diversity within intermittent stream networks: responses to drying and land use. Sci. Total Environ. 935, 173434 (2024).

Mack, L. et al. Perceived multiple stressor effects depend on sample size and stressor gradient length. Water Res. 226, 119260 (2022).

Angradi, T. R. Fine sediment and macroinvertebrate assemblages in Appalachian streams: a field experiment with biomonitoring applications. J. North Am. Benthol. Soc. 18, 49–66 (1999).

Thoetkiattikul, H. et al. Culture-independent study of bacterial communities in tropical river sediment. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 81, 200–209 (2017).

Argudo, M. et al. Responses of resident (DNA) and active (RNA) microbial communities in fluvial biofilms under different polluted scenarios. Chemosphere 242, 125108 (2020).

Astorg, L. et al. Different refuge types dampen exotic invasion and enhance diversity at the whole ecosystem scale in a heterogeneous river system. Biol. Invasions 23, 443–460 (2021).

Azis, M. N. & Abas, A. The determinant factors for macroinvertebrate assemblages in a recreational river in Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia. Environ. Monit. Assess. 193, 394 (2021).

Abdullah, A. H. et al. Macroplastics pollution in the Surma River in Bangladesh: a threat to fish diversity and freshwater ecosystems. Water 14, 3263 (2022).

Szöcs, E., Kefford, B. J. & Schäfer, R. B. Is there an interaction of the effects of salinity and pesticides on the community structure of macroinvertebrates?. Sci. Total Environ. 437, 121–126 (2012).

Casatti, L., Langeani, F. & Ferreira, C. P. Effects of physical habitat degradation on the stream fish assemblage structure in a pasture region. Environ. Manag. 38, 974–982 (2006).

Mazari-Hiriart, M., López-Vidal, Y., Castillo-Rojas, G., De León, S. P. & Cravioto, A. Helicobacter pylori and other enteric bacteria in freshwater environments in Mexico City. Arch. Med. Res. 32, 458–467 (2001).

Camargo, J. A., Alonso, A. & De La Puente, M. Multimetric assessment of nutrient enrichment in impounded rivers based on benthic macroinvertebrates. Environ. Monit. Assess. 96, 233–249 (2004).

Mauad, M., Miserendino, M. L., Risso, M. A. & Massaferro, J. Assessing the performance of macroinvertebrate metrics in the Challhuaco-Ñireco System (Northern Patagonia, Argentina). Iheringia Sér. Zool. 105, 348–358 (2015).

Che Salmah, M. R., Al-Shami, S. A., Abu Hassan, A., Madrus, M. R. & Nurul Huda, A. Distribution of detritivores in tropical forest streams of peninsular Malaysia: role of temperature, canopy cover and altitude variability. Int. J. Biometeorol. 58, 679–690 (2014).

Shahnawaz, A., Venkateshwarlu, M., Somashekar, D. S. & Santosh, K. Fish diversity with relation to water quality of Bhadra River of Western Ghats (India). Environ. Monit. Assess. 161, 83–91 (2010).

Baldigo, B. P., Kulp, M. A. & Schwartz, J. S. Relationships between indicators of acid–base chemistry and fish assemblages in streams of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Ecol. Indic. 88, 465–484 (2018).

Hou, X. et al. The investigation of the physiochemical factors and bacterial communities indicates a low-toxic infectious risk of the Qiujiang River in Shanghai, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 30, 69135–69149 (2023).

Starks, T. A., Long, J. M. & Dzialowski, A. R. Community structure of age-0 fishes in paired mainstem and created shallow-water habitats in the lower Missouri River: age-0 fish communities in Missouri River. River Res. Appl. 32, 753–762 (2016).

Paracampo, A. et al. Fish assemblages in Pampean streams (Buenos Aires, Argentina): relationship to abiotic and anthropic variables. Acad. Bras. Ciênc. 92, e20190476 (2020).

Balázs, A. et al. Comparison of conservation values among man-made aquatic habitats using Odonata communities in Slovakia. Biologia 77, 2549–2561 (2022).

Benítez-Mora, A. & Camargo, J. A. Ecological responses of aquatic macrophytes and benthic macroinvertebrates to dams in the Henares River Basin (Central Spain). Hydrobiologia 728, 167–178 (2014).

Benito, X., Fritz, S. C., Steinitz-Kannan, M., Vélez, M. I. & McGlue, M. M. Lake regionalization and diatom metacommunity structuring in tropical South America. Ecol. Evol. 8, 7865–7878 (2018).

Benoy, G. A., Sutherland, A. B., Culp, J. M. & Brua, R. B. Physical and ecological thresholds for deposited sediments in streams in agricultural landscapes. J. Environ. Qual. 41, 31–40 (2012).

Wolmarans, C. T., Kemp, M., De Kock, K. N. & Wepener, V. The possible association between selected sediment characteristics and the occurrence of benthic macroinvertebrates in a minimally affected river in South Africa. Chem. Ecol. 33, 18–33 (2017).

Ferreira Da Silva, E. et al. Heavy metal pollution downstream the abandoned Coval da Mó mine (Portugal) and associated effects on epilithic diatom communities. Sci. Total Environ. 407, 5620–5636 (2009).

Buendia, C., Gibbins, C. N., Vericat, D., Lopez-Tarazon, J. A. & Batalla, R. J. Influence of naturally high fine sediment loads on aquatic insect larvae in a montane river. Scott. Geogr. J. 127, 315–334 (2011).

Lewis, M. et al. Summer fish community of the coastal northern gulf of mexico: characterization of a large-scale trawl survey. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 136, 829–845 (2007).

Burdon, F. J., McIntosh, A. R. & Harding, J. S. Mechanisms of trophic niche compression: evidence from landscape disturbance. J. Anim. Ecol. 89, 730–744 (2020).

Lin, X., Gao, D., Lu, K. & Li, X. Bacterial community shifts driven by nitrogen pollution in river sediments of a highly urbanized city. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16, 3794 (2019).

Wood, P. J. & Petts, G. E. Low flows and recovery of macroinvertebrates in a small regulated chalk stream. Regul. Rivers Res. Mgmt 9, 303–316 (1994).

Zhang, Y. et al. Characteristics of bacterial communities in a rural river water restored by ecological floating beds with Oenathe javanica. Ecol. Eng. 187, 106823 (2023).

Pound, K. L., Lawrence, G. B. & Passy, S. I. Beta diversity response to stress severity and heterogeneity in sensitive versus tolerant stream diatoms. Divers. Distrib. 25, 374–384 (2019).

Hu, Y. et al. Contrasting patterns of the bacterial and archaeal communities in a high-elevation river in northwestern China. J. Microbiol. 56, 104–112 (2018).

Burdon, F. J., McIntosh, A. R. & Harding, J. S. Habitat loss drives threshold response of benthic invertebrate communities to deposited sediment in agricultural streams. Ecol. Appl. 23, 1036–1047 (2013).

Bilkovic, D. M. Response of tidal creek fish communities to dredging and coastal development pressures in a shallow-water estuary. Estuaries Coasts 34, 129–147 (2011).

Mai, Y. Z., Peng, S. Y. & Lai, Z. N. Structural and functional diversity of biofilm bacterial communities along the Pearl River Estuary, South China. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 33, 100926 (2020).

Cheng, S.-T., Herricks, E. E., Tsai, W.-P. & Chang, F.-J. Assessing the natural and anthropogenic influences on basin-wide fish species richness. Sci. Total Environ. 572, 825–836 (2016).

Collier, K. J., Ilcock, R. J. & Meredith, A. S. Influence of substrate type and physico-chemical conditions on macroinvertebrate faunas and biotic indices of some lowland Waikato, New Zealand, streams. NZ J. Mar. Freshw. Res. 32, 1–19 (1998).

Hunt, G. W. & Stanley, E. H. Environmental factors influencing the composition and distribution of the hyporheic fauna in Oklahoma streams: variation across ecoregions. Arch. Hydrobiol. 158, 1–23 (2003).

Cormier, S. M. et al. Using field data and weight of evidence to develop water quality criteria. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 4, 490–504 (2008).

Cormier, S. M., Suter, G. W., Zheng, L. & Pond, G. J. Assessing causation of the extirpation of stream macroinvertebrates by a mixture of ions. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 32, 277–287 (2013).

Solak, C. N. et al. Use of diatoms in monitoring the Sakarya River Basin, Turkey. Water 12, 703 (2020).

Diamond, J. M., Hall, J. C., Pattie, D. M. & Gruber, D. Use of an integrated monitoring approach to determine site-specific effluent metal limits. Water Environ. Res. 66, 733–743 (1994).

Rasmussen, J. J., McKnight, U. S., Sonne, A. T., Wiberg-Larsen, P. & Bjerg, P. L. Legacy of a chemical factory site: contaminated groundwater impacts stream macroinvertebrates. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 70, 219–230 (2016).

Clapcott, J. E., Young, R. G., Hicks, A. S. & Haidekker, A. N. The 1st step to healthy ecosystems: application of a new integrated assessment framework informs stream management in the Tukituki catchment, New Zealand. Freshw. Sci. 39, 635–651 (2020).

De Almeida Pereira, T., Felisberto, S. A. & De Oliveira Fernandes, V. Longitudinal variation of periphytic algal community structure in a tropical river. Braz. J. Bot. 36, 267–277 (2013).

Datry, T. Benthic and hyporheic invertebrate assemblages along a flow intermittence gradient: effects of duration of dry events. Freshw. Biol. 57, 563–574 (2012).

Morelli, E. & Verdi, A. Diversidad de macroinvertebrados acuáticos en cursos de agua dulce con vegetación ribereña nativa de Uruguay. Rev. Mex. Biodiv. 85, 1160–1170 (2014).

Myers, D. T. L., Rediske, R. R., McNair, J. N., Parker, A. D. & Ogilvie, E. W. Relating environmental variables with aquatic community structure in an agricultural/urban coldwater stream. Ecol. Process 10, 37 (2021).

Hu, C. et al. Phytoremediation of the polluted Waigang River and general survey on variation of phytoplankton population. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 19, 4168–4175 (2012).

Drover, D. R., Zipper, C. E., Soucek, D. J. & Schoenholtz, S. H. Using density, dissimilarity, and taxonomic replacement to characterize mining-influenced benthic macroinvertebrate community alterations in central Appalachia. Ecol. Indic. 106, 105535 (2019).

Echols, B. S., Currie, R. J. & Cherry, D. S. Influence of conductivity dissipation on benthic macroinvertebrates in the North Fork Holston River, Virginia downstream of a point source brine discharge during severe low-flow conditions. Hum. Ecol. Risk Assess. 15, 170–184 (2009).

Feld, C. K., Saeedghalati, M. & Hering, D. A framework to diagnose the causes of river ecosystem deterioration using biological symptoms. J. Appl. Ecol. 57, 2271–2284 (2020).

Gangloff, M. M., Perkins, M., Blum, P. W. & Walker, C. Effects of coal mining, forestry, and road construction on southern Appalachian stream invertebrates and habitats. Environ. Manag. 55, 702–714 (2015).

Wang, L. et al. Shift in the microbial community composition of surface water and sediment along an urban river. Sci. Total Environ. 627, 600–612 (2018).

Gecheva, G. et al. Anthropogenic stressors in upland rivers: aquatic macrophyte responses. A case study from Bulgaria. Plants 10, 2708 (2021).

Göthe, E. et al. Flow restoration and the impacts of multiple stressors on fish communities in regulated rivers. J. Appl. Ecol. 56, 1687–1702 (2019).

Graça, M. A. S. et al. Factors affecting macroinvertebrate richness and diversity in Portuguese streams: a two-scale analysis. Int. Rev. Hydrobiol. 89, 151–164 (2004).

Rosa, B. J. F. V., Rodrigues, L. F. T., De Oliveira, G. S. & Da Gama Alves, R. Chironomidae and Oligochaeta for water quality evaluation in an urban river in southeastern Brazil. Environ. Monit. Assess. 186, 7771–7779 (2014).

Guilpart, A. et al. The use of benthic invertebrate community and water quality analyses to assess ecological consequences of fish farm effluents in rivers. Ecol. Indic. 23, 356–365 (2012).

HaRa, J., Mamun, M. D. & An, K.-G. Ecological river health assessments using chemical parameter model and the index of biological integrity model. Water 11, 1729 (2019).

He, S. et al. Elements of metacommunity structure of diatoms and macroinvertebrates within stream networks differing in environmental heterogeneity. J. Biogeogr. 47, 1755–1764 (2020).

Gücker, B., Brauns, M., Santos, A. T. B., De Carvalho, A. P. C. & Boëchat, I. G. Contrasting effects of agriculture and urban land use on macroinvertebrate secondary production in Neotropical streams. Ecol. Indic. 162, 112039 (2024).

Beyene, A. et al. Comparative study of diatoms and macroinvertebrates as indicators of severe water pollution: case study of the Kebena and Akaki rivers in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Ecol. Indic. 9, 381–392 (2009).

Johnson, K. S., Thompson, P. C., Gromen, L. & Bowman, J. Use of leaf litter breakdown and macroinvertebrates to evaluate gradient of recovery in an acid mine impacted stream remediated with an active alkaline doser. Environ. Monit. Assess. 186, 4111–4127 (2014).