Abstract

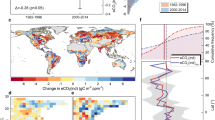

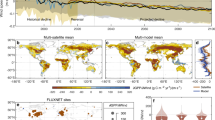

Previous projections from Earth system models have suggested that rising atmospheric CO2 concentrations would stimulate global vegetation production through the CO2 fertilization effect. Here we show that increased atmospheric dryness driven by climate warming will substantially counteract this effect. Using measurements from global eddy-covariance sites and a process-based model, we project that global vegetation gross primary production (GPP) will peak around the middle of the twenty-first century and subsequently decline. The peak of global GPP is projected to increase by only 5.4 ± 0.5% compared with the present. The stalled increase in GPP is more prominent in tropical regions. Additionally, the increased atmospheric dryness resulting from two non-CO2 greenhouse gases (CH4 and N2O) plays an important role in GPP changes. These gases induce climate warming and atmospheric dryness but, unlike CO2, lack a fertilization effect. This study underscores that climate warming-induced atmospheric dryness markedly reduces terrestrial vegetation production, potentially limiting the terrestrial carbon sink in the future.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All data used in this study are openly available from the following: CMIP6 output (https://aims2.llnl.gov/search/cmip6/); ERA5 (https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/cdsapp#!/dataset/reanalysis-era5-land?tab=overview); FLUXNET 2015 (https://fluxnet.org/data/fluxnet2015-dataset/); ICOS (https://www.icos-cp.eu/data-products/2G60-ZHAK); AmeriFlux (https://ameriflux.lbl.gov/sites/site-search/); OzFlux (https://data.ozflux.org.au/home.jspx); AsiaFlux (https://db.cger.nies.go.jp/asiafluxdb/); and GLASS-LAI (https://glass.hku.hk/archive/LAI/MODIS/500M/). Any additional information may be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Matlab code for the rEC-LUE-v.2 performed in this study is available via Code Ocean at https://doi.org/10.24433/CO.4541304.v1

References

Chapin, F. S. et al. Earth stewardship: a strategy for social–ecological transformation to reverse planetary degradation. J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 1, 44–53 (2011).

Yuan, W. et al. Redefinition and global estimation of basal ecosystem respiration rate. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 25, GB4002 (2011).

Keenan, T. F. et al. Recent pause in the growth rate of atmospheric CO2 due to enhanced terrestrial carbon uptake. Nat. Commun. 7, 13428 (2016).

Zhao, M. et al. Drought-induced reduction in global terrestrial net primary production from 2000 through 2009. Science 1667, 2–5 (2010).

Beer, C. et al. Terrestrial gross carbon dioxide uptake: global distribution and covariation with climate. Science 329, 834–838 (2010).

Zhou, S. et al. Projected increases in intensity, frequency, and terrestrial carbon costs of compound drought and aridity events. Sci. Adv. 5, eaau5740 (2019).

Tian, C. et al. Projections of changes in ecosystem productivity under 1.5 °C and 2 °C global warming. Glob. Planet. Change 205, 103588 (2021).

Smith, W. K. et al. Large divergence of satellite and Earth system model estimates of global terrestrial CO2 fertilization. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 306–310 (2016).

Wang, S. et al. Recent global decline of CO2 fertilization effects on vegetation photosynthesis. Science 370, 1295–1300 (2020).

Li, S. et al. Vegetation growth due to CO2 fertilization is threatened by increasing vapor pressure deficit. J. Hydrol. 619, 129292 (2023).

He, B. et al. Worldwide impacts of atmospheric vapor pressure deficit on the interannual variability of terrestrial carbon sinks. Natl Sci. Rev. 9, nwab150 (2021).

Fu, Z. et al. Atmospheric dryness reduces photosynthesis along a large range of soil water deficits. Nat. Commun. 13, 989 (2022).

Lu, H. et al. Large influence of atmospheric vapor pressure deficit on ecosystem production efficiency. Nat. Commun. 13, 1653 (2022).

Yuan, W. et al. Increased atmospheric vapor pressure deficit reduces global vegetation growth. Sci. Adv. 5, eaax1396 (2019).

Grossiord, C. et al. Plant responses to rising vapor pressure deficit. New Phytol. 226, 1550–1566 (2020).

Fang, Z. et al. Globally increasing atmospheric aridity over the 21st century. Earth’s Future 10, e2022EF003019 (2022).

IPCC. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis (eds Masson-Delmotte, V. et al.) (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2021).

Xin, Q. et al. A semiprognostic phenology model for simulating multidecadal dynamics of global vegetation leaf area index. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 12, e2019MS001935 (2020).

Ma, H. et al. Development of the GLASS 250-m leaf area index product (version 6) from MODIS data using the bidirectional LSTM deep learning model. Remote Sens. Environ. 273, 112985 (2022).

Yan, K. et al. HiQ-LAI: a high-quality reprocessed MODIS LAI dataset with better spatio-temporal consistency from 2000 to 2022. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 16, 1601–1622 (2023).

Lin, W. et al. Reprocessed MODIS version 6.1 leaf area index dataset and its evaluation for land surface and climate modeling. Remote Sens. 15, 1780 (2023).

He, Y. et al. CO2 fertilization contributed more than half of the observed forest biomass increase in northern extra-tropical land. Glob. Change Biol. 29, 4313–4326 (2023).

Chen, C. et al. CO2 fertilization of terrestrial photosynthesis inferred from site to global scales. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2115627119 (2022).

Obermeier, W. A. et al. Reduced CO2 fertilization effect in temperate C3 grasslands under more extreme weather conditions. Nat. Clim. Change 7, 137–141 (2017).

Wang, S. et al. Drylands contribute disproportionately to observed global productivity increases. Sci. Bull. 68, 224–232 (2023).

Cai, W. et al. Large differences in terrestrial vegetation production derived from satellite-based light use efficiency models. Remote Sens. 6, 8945–8965 (2014).

Huang, M. et al. Air temperature optima of vegetation productivity across global biomes. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 3, 772–779 (2019).

Yuan, W. et al. Severe summer heatwave and drought strongly reduced carbon uptake in Southern China. Sci. Rep. 6, 18813 (2016).

Liu, L. et al. Soil moisture dominates dryness stress on ecosystem production globally. Nat. Commun. 11, 4892 (2020).

Yuan, W. et al. China’s greenhouse gas budget during 2000–2023. Natl Sci. Rev. 12, nwaf069 (2025).

Zhang, S. & Chen, W. Assessing the energy transition in China towards carbon neutrality with a probabilistic framework. Nat. Commun. 13, 87 (2022).

Ou, Y. et al. Deep mitigation of CO2 and non-CO2 greenhouse gases toward 1.5 °C and 2 °C futures. Nat. Commun. 12, 6245 (2021).

Edelenbosch, O. et al. Reducing sectoral hard-to-abate emissions to limit reliance on carbon dioxide removal. Nat. Clim. Change 14, 715–722 (2024).

IPCC. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report (eds Core Writing Team, Lee, H. & and Romero, J.) (IPCC, 2023).

Zhu, Z. et al. Greening of the Earth and its drivers. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 791 (2016).

Huang, K. et al. Enhanced peak growth of global vegetation and its key mechanisms. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2, 1897–1905 (2018).

McDowell, N. G. et al. Mechanisms of woody-plant mortality under rising drought, CO2 and vapour pressure deficit. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 3, 294–308 (2022).

Munson, S. M. et al. Ecosystem thresholds, tipping points, and critical transitions. New Phytol. 218, 1315–1317 (2018).

Niu, S. et al. Plant growth and mortality under climatic extremes: an overview. Environ. Exp. Bot. 98, 13–19 (2014).

Knauer, J. et al. Higher global gross primary productivity under future climate with more advanced representations of photosynthesis. Sci. Adv. 9, eadh9444 (2023).

Liu, J. et al. Evidence for widespread thermal acclimation of canopy photosynthesis. Nat. Plants 10, 1919–1927 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. Increasing optimum temperature of vegetation activity over the past four decades. Earths Future 12, e2024EF004489 (2024).

Wu, T. et al. Leaf photosynthetic and respiratory thermal acclimation in terrestrial plants in response to warming: a global synthesis. Glob. Change Biol. 31, e70026 (2025).

Du, Q. et al. Leaf anatomical adaptations have central roles in photosynthetic acclimation to humidity. J. Exp. Bot. 70, 4949–4962 (2019).

Lopez, J. et al. Systemic effects of rising atmospheric vapor pressure deficit on plant physiology and productivity. Glob. Change Biol. 27, 1704–1720 (2021).

Chen, I. C. et al. Rapid range shifts of species associated with high levels of climate warming. Science 333, 1024–1026 (2011).

Luo, X. et al. Mapping the global distribution of C4 vegetation using observations and optimality theory. Nat. Commun. 15, 1219 (2024).

Van Der Sleen, P. et al. No growth stimulation of tropical trees by 150 years of CO2 fertilization but water-use efficiency increased. Nat. Geosci. 8, 24–28 (2015).

Jiang, M. et al. The fate of carbon in a mature forest under carbon dioxide enrichment. Nature 580, 227–231 (2020).

Pastorello, G. et al. The FLUXNET2015 dataset and the ONEFlux processing pipeline for eddy covariance data. Sci. Data 7, 225 (2020).

Myneni, R. et al. MODIS/terra leaf area index/FPAR 8-day L4 global 500m SIN grid V061. LP DAAC https://doi.org/10.5067/MODIS/MOD15A2H.061 (2021).

Dhorde, A. G. et al. Spatio-temporal variation in terminal drought over western India using dryness index derived from long-term MODIS data. Ecol. Inform. 32, 28–38 (2016).

Mariano, D. A. et al. Use of remote sensing indicators to assess effects of drought and human-induced land degradation on ecosystem health in Northeastern Brazil. Remote Sens. Environ. 213, 129–143 (2018).

Meinshausen, M. et al. The shared socio-economic pathway (SSP) greenhouse gas concentrations and their extensions to 2500. Geosci. Model Dev. 13, 3571–3605 (2020).

He, M. et al. Evaluation and improvement of MODIS gross primary productivity in typical forest ecosystems of East Asia based on eddy covariance measurements. J. For. Res. 18, 31–40 (2013).

Forzieri, G. et al. Increased control of vegetation on global terrestrial energy fluxes. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 356–362 (2020).

Schroeder, M. A. et al. Diagnosing and dealing with multicollinearity. West. J. Nurs. Res. 12, 175–187 (1990).

Graham, M. H. Confronting multicollinearity in ecological multiple regression. Ecology 84, 2809–2815 (2003).

Yamori, W. et al. Temperature acclimation of photosynthesis in spinach leaves: analyses of photosynthetic components and temperature dependencies of photosynthetic partial reactions. Plant Cell Environ. 28, 536–547 (2005).

Fu, Z. et al. Critical soil moisture thresholds of plant water stress in terrestrial ecosystems. Sci. Adv. 8, eabq7827 (2022).

Huang, X. et al. Improving the global MODIS GPP model by optimizing parameters with fluxnet data. Agric. For. Meteorol. 300, 108314 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This study is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 42141020 and 42101319), National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant no. 2023YFF1303602) and the Science and Technology Program of Guangdong (no. 2024B1212070012).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.L., X.C. and W.Y. conceived the study. S.L., W.Y., J.X. and X.C. contributed to early-stage discussions. S.L. collected and preprocessed the data and the code. S.L., J.X. and W.Y. performed the analysis, led the result interpretation and drafted the initial paper. X.C., Q.X., Z.F., B.H., Q.L. and S.P. contributed to the development and discussion of the methods. All co-authors reviewed the results and contributed to the writing and revision of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Ecology & Evolution thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Methods, Figs. 1–19 and Tables 1–4.

Supplementary Data 1

Source geotiff data for Fig. 4e which should be open as .geotiff format with Arcmap or Python script. The numbers in the .tif file are the years.

Supplementary Data 2

Source geotiff data for Fig. 4f which should be open as .geotiff format with Arcmap or Python script. The numbers in the .tif file are the years.

Supplementary Data 3

Source geotiff data for Fig. 4g which should be open as .geotiff format with Arcmap or Python script. The numbers in the .tif file are the years.

Supplementary Data 4

Source geotiff data for Fig. 4h which should be open as .geotiff format with Arcmap or Python script. The numbers in the .tif file are the years.

Source data

Source Data Figs. 1–5

Statistical source data for Fig. 1a,b, Fig. 2a–e and Fig. 3a–h (unit in gC MJ−1 m−2); Fig. 4a–d (unit in PgC yr−1); Fig. 5a–d (unit in hPa); Fig. 5e–h (unit in PgC yr−1).

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, S., Chen, X., Xia, J. et al. Global vegetation production may decrease in this century due to rising atmospheric dryness. Nat Ecol Evol 9, 2279–2289 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-025-02885-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-025-02885-3