Abstract

Anaerobic ammonium oxidation (anammox) bacteria contribute to nearly half of global nitrogen loss. However, the driving force responsible for the origin of anammox bacteria remains poorly understood. Here we show that anammox bacteria can oxidize ammonium to N2 for growth using photoholes—the positive charge carriers generated from photosensitizers—potentially supporting their origin. Such photoholes could have been generated in sunlit benthic environments by cyanobacterial mats and semiconducting minerals under the intense solar radiation of the Late Archaean (3.0–2.5 billion years ago). Moreover, cyanobacterial mats absorbed harmful short-wavelength light for anammox bacteria, while allowing longer-wavelength infrared light to penetrate. Light-driven enrichment of nitrite-reductase-deficient anammox bacteria in long-term-cultured cyanobacterial mats, DNA stable-isotope probing and evolutionary analysis collectively suggest that the ancestral anammox bacteria tended to be photoelectrotrophic instead of nitrite-dependent. Our discovery provides a paradigm shift in our understanding of the origin of ammonium oxidation and may explain the nitrogen loss on early Earth.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All raw metagenomes and metatranscriptomes are deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive under BioProject accession numbers PRJNA1144341 and PRJNA1260665. All information on the publicly available MAGs used in this study is provided in Supplementary Datasets 2 and 3. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Analysis scripts are publicly available at https://github.com/zhengru-pku/Metatranscriptomic_analyze.

References

Humbert, S. et al. Molecular detection of anammox bacteria in terrestrial ecosystems: distribution and diversity. ISME J. 4, 450–454 (2010).

Sun, J. et al. Potential growth of anammox bacteria under aerobic conditions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 58, 18244–18254 (2024).

Lawson, C. E. et al. Autotrophic and mixotrophic metabolism of an anammox bacterium revealed by in vivo 13C and 2H metabolic network mapping. ISME J. 15, 673–687 (2021).

Shaw, D. R. et al. Extracellular electron transfer-dependent anaerobic oxidation of ammonium by anammox bacteria. Nat. Commun. 11, 2058 (2020).

Cuecas, A., Barrau, M. J. & Gonzalez, J. M. Microbial divergence and evolution. The case of anammox bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 15, 1355780 (2024).

Liao, T. et al. Phylogenomic evidence for the origin of obligate anaerobic anammox bacteria around the Great Oxidation Event. Mol. Biol. Evol. 39, msac170 (2022).

Lyons, T. W. et al. Co-evolution of early Earth environments and microbial life. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 22, 572–586 (2024).

Liao, T. et al. Dating ammonia-oxidizing bacteria with abundant eukaryotic fossils. Mol. Biol. Evol. 41, msae096 (2024).

Kartal, B. et al. Molecular mechanism of anaerobic ammonium oxidation. Nature 479, 127–130 (2011).

Planavsky, N. J. et al. Widespread iron-rich conditions in the mid-Proterozoic ocean. Nature 477, 448–451 (2011).

Zhu-Barker, X. et al. The importance of abiotic reactions for nitrous oxide production. Biogeochemistry 126, 251–267 (2015).

Buessecker, S. et al. Mineral-catalysed formation of marine NO and N2O on the anoxic early Earth. Nat. Geosci. 15, 1056–1063 (2022).

Parsons, C. et al. Radiation of nitrogen-metabolizing enzymes across the tree of life tracks environmental transitions in Earth history. Geobiology 19, 18–34 (2021).

Maza-Márquez, P. et al. Millimeter-scale vertical partitioning of nitrogen cycling in hypersaline mats reveals prominence of genes encoding multi-heme and prismane proteins. ISME J. 16, 1119–1129 (2022).

Gutiérrez-Preciado, A. et al. Functional shifts in microbial mats recapitulate early Earth metabolic transitions. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2, 1700–1708 (2018).

Stüeken, E. E. et al. Marine biogeochemical nitrogen cycling through Earth’s history. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 5, 732–747 (2024).

Li, Y. et al. Photoreduction of inorganic carbon(+IV) by elemental sulfur: implications for prebiotic synthesis in terrestrial hot springs. Sci. Adv. 6, eabc3687 (2020).

Sánchez-Baracaldo, P. et al. Cyanobacteria and biogeochemical cycles through Earth history. Trends Microbiol. 30, 143–157 (2022).

Wiegand, S., Jogler, M. & Jogler, C. On the maverick Planctomycetes. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 42, 739–760 (2018).

Klawonn, I. et al. Aerobic and anaerobic nitrogen transformation processes in N2-fixing cyanobacterial aggregates. ISME J. 9, 1456–1466 (2015).

Goldman, A. D. et al. Electron transport chains as a window into the earliest stages of evolution. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2210924120 (2023).

Ming, J. et al. Photocatalytic material–microorganism hybrid systems in water decontamination. Trends Biotechnol. 43, 1031–1047 (2025).

Huang, S. et al. Dissolved organic matter acting as a microbial photosensitizer drives photoelectrotrophic denitrification. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 4632–4641 (2022).

Chen, S. et al. Biophotoelectrochemical process co-driven by dead microalgae and live bacteria. ISME J. 17, 712–719 (2023).

Cheng, H. et al. Sunlight-triggered synergy of hematite and Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 in Cr(VI) removal. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 305, 19–32 (2021).

Kong, L. et al. Anammox bacteria adapt to long-term light irradiation in photogranules. Water Res. 241, 120144 (2023).

Zhang, L. et al. Anammox coupled with photocatalyst for enhanced nitrogen removal and the activated aerobic respiration of anammox bacteria based on cbb3-type cytochrome c oxidase. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 17910–17919 (2023).

Guo, M., Wang, C. & Qiao, S. Light-driven ammonium oxidation to dinitrogen gas by self-photosensitized biohybrid anammox systems. iScience 26, 106725 (2023).

Hu, P. et al. The core anammox redox reaction system of 12 anammox bacterial genera and their evolution and application implications. Water Res. 281, 123551 (2025).

Kong, L. et al. Interspecies hydrogen transfer between cyanobacteria and symbiotic bacteria drives nitrogen loss. Nat. Commun. 16, 5078 (2025).

Zheng, R. et al. Blue-light irradiation induced partial nitrification. Water Res. 254, 121381 (2024).

Lu, A. et al. Growth of non-phototrophic microorganisms using solar energy through mineral photocatalysis. Nat. Commun. 3, 768 (2012).

Zhang, J. et al. Accumulation of long-lived photogenerated holes at indium single-atom catalysts via two coordinate nitrogen vacancy defect engineering for enhanced photocatalytic oxidation. Adv. Mater. 36, 2309205 (2024).

Okubo, T. et al. The physiological potential of anammox bacteria as revealed by their core genome structure. DNA Res. 28, dsaa028 (2020).

Maalcke, W. J. et al. Structural basis of biological NO generation by octaheme oxidoreductases. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 1228–1242 (2014).

Oshiki, M. et al. Hydroxylamine-dependent anaerobic ammonium oxidation (anammox) by “Candidatus Brocadia sinica”. Environ. Microbiol. 18, 3133–3143 (2016).

Hu, Z. et al. Nitric oxide-dependent anaerobic ammonium oxidation. Nat. Commun. 10, 1244 (2019).

Huang, B.-C. et al. Light-driven electron uptake from nonfermentative organic matter to expedite nitrogen dissimilation by chemolithotrophic anammox consortia. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 12732–12740 (2023).

Trebuch, L. M. et al. High resolution functional analysis and community structure of photogranules. ISME J. 17, 870–879 (2023).

Davis, S. J., Vener, A. V. & Vierstra, R. D. Bacteriophytochromes: phytochrome-like photoreceptors from nonphotosynthetic eubacteria. Science 286, 2517–2520 (1999).

Wang, R. et al. Unraveling sources of cyanate in the marine environment: insights from cyanate distributions and production during the photochemical degradation of dissolved organic matter. Front. Mar. Sci. 11, 1373643 (2024).

Zhao, R., Biddle, J. F. & Jørgensen, S. L. Introducing Candidatus Bathyanammoxibiaceae, a family of bacteria with the anammox potential present in both marine and terrestrial environments. ISME Commun. 2, 42 (2022).

Wisniewski-Dyé, F. et al. Azospirillum genomes reveal transition of bacteria from aquatic to terrestrial environments. PLoS Genet. 7, e1002430 (2011).

Moran, M. A. & Miller, W. L. Resourceful heterotrophs make the most of light in the coastal ocean. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5, 792–800 (2007).

Wu, J. et al. Novel anammox bacteria discovered in the untapped subsurface aquifers. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.04.27.538623 (2023).

Lodha, T., Narvekar, S. & Karodi, P. Classification of uncultivated anammox bacteria and Candidatus Uabimicrobium into new classes and provisional nomenclature as Candidatus Brocadiia classis nov. and Candidatus Uabimicrobiia classis nov. of the phylum Planctomycetes and novel family Candidatus Scalinduaceae fam. nov to accommodate the genus Candidatus Scalindua. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 44, 126272 (2021).

Ren, M. et al. Phylogenomics suggests oxygen availability as a driving force in Thaumarchaeota evolution. ISME J. 13, 2150–2161 (2019).

Chicano, T. M. et al. Structural and functional characterization of the intracellular filament-forming nitrite oxidoreductase multiprotein complex. Nat. Microbiol. 6, 1129–1139 (2021).

Han, X. et al. Origin and evolution of core components responsible for monitoring light environment changes during plant terrestrialization. Mol. Plant 12, 847–862 (2019).

Peng, M.-W. et al. Insight into the structure and metabolic function of iron-rich nanoparticles in anammox bacteria. Sci. Total Environ. 806, 150879 (2022).

Helmbrecht, V. et al. Simulated early Earth geochemistry fuels a hydrogen-dependent primordial metabolism. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 9, 769–778 (2025).

Liu, J. et al. Extracellular electron transfer of electrochemically active bacteria community promoted by semiconducting minerals with photo-response in marine euphotic zone. Geomicrobiol. J. 38, 329–339 (2021).

Liu, T. et al. Sustainable wastewater management through nitrogen-cycling microorganisms. Nat. Water 2, 936–952 (2024).

Rios, E. et al. Anaerobic ammonium oxidation linked to microbial reduction of natural organic matter in marine sediments. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 5, 571–577 (2018).

Garcias-Bonet, N. et al. High denitrification and anaerobic ammonium oxidation contributes to net nitrogen loss in a seagrass ecosystem in the central Red Sea. Biogeosciences 15, 7333–7346 (2018).

Garvin, J. et al. Isotopic evidence for an aerobic nitrogen cycle in the latest Archean. Science 323, 1045–1048 (2009).

Godfrey, L. V. & Falkowski, P. G. The cycling and redox state of nitrogen in the Archaean ocean. Nat. Geosci. 2, 725–729 (2009).

Koehler, M. C. et al. Transient surface ocean oxygenation recorded in the ∼2.66-Ga Jeerinah Formation, Australia. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 7711–7716 (2018).

Martin, A. N. et al. Anomalous δ15N values in the Neoarchean associated with an abundant supply of hydrothermal ammonium. Nat. Commun. 16, 1873 (2025).

Bian, J. et al. Bioinspired Fe single-atom nanozyme synergizes with natural NarGH dimer for high-efficiency photobiocatalytic nitrate conversion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.5c07315 (2025).

Bian, J. et al. Directional electron transfer in enzymatic nano-bio hybrids for selective photobiocatalytic conversion of nitrate. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202412194 (2024).

Kang, D. et al. MetaBAT, an efficient tool for accurately reconstructing single genomes from complex microbial communities. PeerJ 3, e1165 (2015).

Menzel, P., Ng, K. L. & Krogh, A. Fast and sensitive taxonomic classification for metagenomics with Kaiju. Nat. Commun. 7, 11257 (2016).

Chaumeil, P.-A. et al. GTDB-Tk: a toolkit to classify genomes with the Genome Taxonomy Database. Bioinformatics 36, 1925–1927 (2019).

Zhou, Z. et al. METABOLIC: high-throughput profiling of microbial genomes for functional traits, metabolism, biogeochemistry, and community-scale functional networks. Microbiome 10, 33 (2022).

Buchfink, B., Xie, C. & Huson, D. H. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods 12, 59–60 (2015).

Wagner, G. P., Kin, K. & Lynch, V. J. Measurement of mRNA abundance using RNA-seq data: RPKM measure is inconsistent among samples. Theory Biosci. 131, 281–285 (2012).

Kong, L. et al. Cross-feeding between filamentous cyanobacteria and symbiotic bacteria favors rapid photogranulation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 16953–16963 (2023).

Tadic, M. et al. Magnetic properties of hematite (α-Fe2O3) nanoparticles prepared by hydrothermal synthesis method. Appl. Surf. Sci. 320, 183–187 (2014).

Neufeld, J. D. et al. DNA stable-isotope probing. Nat. Protoc. 2, 860–866 (2007).

Kang, D. et al. Deciphering correlation between chromaticity and activity of anammox sludge. Water Res. 185, 116184 (2020).

Reis, M. D. & Yang, Z. Approximate likelihood calculation on a phylogeny for Bayesian estimation of divergence times. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28, 2161–2172 (2011).

Zhao, R. et al. Age, metabolisms, and potential origin of dominant anammox bacteria in the global oxygen-deficient zones. ISME Commun. 4, ycae060 (2024).

Misawa, K. et al. MAFFT: a novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 3059–3066 (2002).

Nguyen, L.-T. et al. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32, 268–274 (2014).

Davín, A. A. et al. A geological timescale for bacterial evolution and oxygen adaptation. Science 388, eadp1853 (2025).

Szollosi, G. et al. Efficient exploration of the space of reconciled gene trees. Syst. Biol. 62, 901–912 (2013).

Moody, E. R. R. et al. The nature of the last universal common ancestor and its impact on the early Earth system. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 8, 1654–1666 (2024).

Jumper, J. et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 596, 583–589 (2021).

Pettersen, E. F. et al. UCSF ChimeraX: structure visualization for researchers, educators, and developers. Protein Sci. 30, 70–82 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (W2412119 (S.L.), 52270016 (S.L.), 52200029 (K.Z.) and 523B2095 (L.K.)) and Peking University-BHP Carbon and Climate Wei-Ming PhD Scholars (WM202510 (L.K.)). We are grateful for the support of the High-Performance Computing Platform of Peking University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.L., L.K. and R.Z. designed the study. L.K., R.Z. and J.F. conducted the research with the help of Y.F., B.C., Y.M., J.W. and A.C. K.Z., L.K., R.Z. and S.L. wrote the paper. Y.F. and B.C. performed the software analysis. Y.M., J.W. and A.C. investigated the related information. All the authors contributed to the interpretation of the findings.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Ecology & Evolution thanks Tianhua Liao, Eva Stüeken and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 EPR spectroscopy of the cyanobacterial mats.

(a) The EPR signal was detected in the presence of 5 mM spin probe TEMPO in cyanobacterial mats under dark conditions. (b) The TEMPO signal was detected with the addition of electron scavenger (5 mM AgNO3) in cyanobacterial mats under light conditions. All EPR spectra were recorded at room temperature (25 °C) and recorded every 5 minutes with the following instrumental parameters: center magnetic field, 3505.00 G; modulation frequency, 100.00 kHz; modulation amplitude, 1.000 G; microwave power, 0.6325 mW; sweep width, 100.0 G; and sweep time, 30 s. Magnified views of the selected region were shown to highlight subtle variations in signal intensity.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Expression of genes in enriched AMX1 at different days during the reactor operation.

Gene expression levels, quantified as Log2(TPM + 1), are shown for metatranscriptomic samples collected at key time points: under dark conditions on day 60 and under light conditions on days 200 and 450. Rows denote genes categorized by function, including light sensing and adaptation, nitrogen metabolism, electron transfer, and cyanate assimilation. The gene encoding hydrazine synthase subunit C (hzsC) was not detected in the AMX1 genome, likely due to the incompleteness of the recovered MAG. For each condition, TPM values represent the mean ± standard deviation derived from three biological replicates.

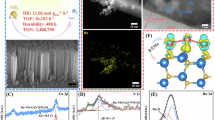

Extended Data Fig. 3 Morphological and structural characterization of hematite and hematite-anammox biohybrid system.

(a) Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image showing the morphology of the hematite-anammox biohybrid system. Micrographs are representative results from 10 independent images. (b) Energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) mapping highlighting the distribution of the Fe element. (c) EDS mapping showing the distribution of the C element within the biohybrid system. (d) EDS mapping illustrating the distribution of the O element. (e) X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) spectrum of hematite, revealing characteristic binding energies of Fe, O, and C. (f) X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern of hematite, with key diffraction peaks corresponding to hematite (indexed in blue).

Extended Data Fig. 4 Formation of iron mineral on the surface of cyanobacterial mats.

SEM-EDS analysis of cyanobacterial mats collected from the photobioreactor on day 450. The SEM image shows cyanobacterial filaments partially covered by granular deposits identified as iron oxides. Elemental mapping of Fe, O, and C reveals strong co-localization of Fe and O, with negligible carbon signal, indicating the formation of iron mineral coatings on the cyanobacterial surface. Micrographs are representative results from 10 independent images.

Extended Data Fig. 5 The gene expression profile of anammox bacteria during the batch assays of biophotoelectrochemical ammonium oxidation.

Gene expression profiles (in terms of TPM) of three recovered MAGs of anammox bacteria (AMX1–3) under different experimental conditions: hematite-anammox biohybrid under illumination with ammonium (R0), anammox consortia without hematite under illumination (R1), and dark anammox consortia supplied with ammonium and nitrite (R2). TPM values represent means of three biological replicates. Red and blue indicate up- and down-regulated genes, respectively. Statistical significance was assessed using an unpaired two-sided Student’s t-test (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; **P < 0.001).

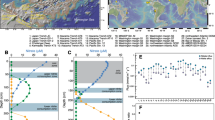

Extended Data Fig. 6 The variation of specific anammox activity (SAA) over time in the batch assays under different light conditions.

(a) Blue light groups. (b) Infrared light groups. (c) White light groups. Batch assays were conducted under a light intensity of 8000 lux, with each illuminated group paired with a corresponding dark control. Specific anammox activity (SAA) was calculated based on the substrate consumption rate to evaluate the metabolic activity of anammox bacteria over time. Data represent mean ± s.d. of three biological replicates. Statistical significance was determined using a two-tailed Student’s t-test (*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; **P < 0.001).

Extended Data Fig. 7 Co-occurrence network of the microbial community.

The network was constructed at the genus level based on Spearman’s correlation coefficients across all metagenomic samples collected during the reactor operation. Node size corresponds to the relative abundance of each genus. A threshold of R > 0.7 and P < 0.05 was used to filter for genera most strongly correlated with anammox bacteria (Ca. Brocadia) and cyanobacteria (Leptolyngbya).

Extended Data Fig. 8 Phylogenetic analysis of genes encoding bacterioferritin and hydrazine synthase from anammox bacteria.

(a) Phylogenetic tree of genes encoding bacterioferritin (bfr). (b) Phylogenetic tree of genes encoding hydrazine synthase subunit A (hzsA). Trees show the classification of these sequences from different anammox bacterial lineages. The phylogenetic tree is constructed based on the alignments of gene sequences from all anammox reference MAGs used in Supplementary Dataset 3. All conserved protein phylogenomic and phylogenetic alignments are based on MAFFT, and the trees that were built by the IQ-Tree method with model LG + C60 + F + G using SH approximate likelihood ratio test implemented with 1000 bootstrap replicates with bootstrap higher than 0.8 are shown with grey squares on tree branches.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Texts 1–7, Figs. 1–7 and Tables 1–3.

Supplementary Datasets 1–4

This Excel file contains Supplementary Datasets 1–4. The title and description are provided within the file itself.

Source data

Source Data Figs. 1–3 and Extended Data Figs. 1–3, 5 and 6

Source data for all figures and Extended Data figures.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Kong, L., Zheng, R., Feng, J. et al. Photoholes within cyanobacterial mats can account for the origin of anammox bacteria and ancient nitrogen loss. Nat Ecol Evol (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-026-02976-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-026-02976-9