Abstract

Connecting research on the water demand of power plants with mitigation strategies for energy-based water use is an important step to ensure global water and energy security, and thus provide more sustainable use of both. Here, we assess the water footprint of 13,863 thermal power plants units with a total active capacity of 4,182 GW worldwide and give an estimate of the current water demand for power production at four different levels—global, regional, country and river. Furthermore, we provide a projection for the energy transition period towards a net zero greenhouse gas emissions economy by 2050. In particular, we show that by following a ‘Best Policies Scenario’ the water consumption of global power plants can be decreased by about 98%, and water withdrawal by 95% by 2050. Therefore, the suggested pathway provides one potential solution to the problem of water depletion that results from the water-energy nexus.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Water and energy are closely related. Thermal electricity generation constituted of coal, gas, oil, biomass and nuclear power plants requires water for cooling purposes. Water is also used in numerous technological processes to harness, extract and produce energy. Meanwhile, water extraction, treatment and distribution consume energy. This dependency is often called the water-energy nexus and is increasingly highlighted by many scholars and policymakers as a sustainability concern for future planning and for water security1,2,3.

The currently used technologies of thermal power generation heavily depend on water availability. Water scarcity, often perceived as a side issue of climate change, directly affects the capacity and reliability of thermal power. Moreover, increased water temperatures and reduced river flow have led to forced reductions or even interruptions in power generation4,5 worldwide. This limitation to electricity supply, coupled with rising production costs, may lead to a sharp rise in electricity prices6,7.

Thus, it is crucial to understand the contributors to global water stress, one of which is the cooling water demand of thermal power plants, and implement strategies to overcome water resource depletion. The water footprint of cooling the global power plant fleet is typically analysed from the perspective of water withdrawal and water consumption8. Water withdrawal is defined as the total amount of water taken from the water source for cooling purposes. Water consumption represents the difference between water withdrawal and the amount of water returned to the source, and water is often ‘lost’ by means of evaporation9.

Currently, research on the water demand of power plants is conducted using different estimation techniques (satellite images10,11, historical data12 and statistical data8,13), which is not commonly reported. Macknick et al.14 reported water withdrawal and consumption factors for different thermal power plants in the United States. Owing to the lack of country-specific water demand data for thermal power plants, the factors provided by Macknick et al. were used in recent global studies on water withdrawal and consumption. Studies so far have focused on either the global8,12,13,15,16 or regional and country1,10,11,17 level. The research conducted by Flörke et al.12 and Vassolo and Döll16 is the base on which the commonly used Global Water System Project (GWSP) Digital Water Atlas18 was produced. Subsequent studies on the water demand for the cooling of thermal power plants expand on the results of Flörke et al.12, with the aim to generate comprehensive insights into a sector that plays a crucial role in the global water stress.

The main concern with estimating the water demand of the global thermal power plant fleet is the limited availability of data on the cooling technologies and the water source (seawater or freshwater) used for cooling8,12,16. In this research, we strive to overcome these limitations.

It is crucial to determine how the world’s hunger for electricity can be met and also reduce the power sector’s thirst for water. Behrens at al.1 discussed the vulnerability of power generation to water scarcity and water temperature on the basin level and suggested adaptation strategies for the European Union. However, the authors did not include the ongoing development to replace once-through cooling systems by cooling towers. In contrast to once-through cooling systems, cooling towers, even though consuming large amounts of water, do not cause a temperature increase in downstream basins. In addition, unscheduled outages related to cooling water supply shortages at thermal power plants with cooling towers are minor and uncommon4. Maulbetsch and Stallings19 discuss dry cooling, which results in an estimated cost reduction related to water conservation of $0.81–1.62 m–3 of saved water, which is, in magnitude, comparable to tap water usage. However, along with high costs and material requirements for the cooling system set-up, dry cooling decreases the power plant efficiency. This leads to an increase in greenhouse gas emissions, which counteracts the targets imposed by the IPCC Special Report Global Warming of 1.5° (SR1.5)20. Therefore, dry cooling has a limited application and can be sustainably implemented only in cases of high thermal efficiency and low cooling needs, for instance, in combined cycle gas turbines. When discussing various approaches to mitigate the water demand of thermal power plants, it is crucial to consider the development of renewable energy as a solution to the problem of water scarcity.

According to Roehrkasten et al.5, over their entire lifecycle both solar photovoltaic systems and wind turbines withdraw and consume 2–15% and 0.1–14%, respectively, of the water that coal or nuclear power plants use to generate 1 MWh of electricity. In this regard, renewable energy represents a viable solution as it couples almost zero greenhouse gas emissions with very low to negligible water demand for power generation. Recent research highlighted that a high share of renewable energy is technically feasible and economically viable and, with the support of policy changes, can be implemented globally in the future21,22,23,24,25. However, this reality is not certain to happen. Following these insights, it is relevant and necessary to estimate the development of water demand in a world with increasing shares of renewable energy.

We determined the cooling technology of individual power plants and performed an analysis for the seawater and freshwater demand of the global thermal power plant fleet. Our research is based on the GlobalData dataset26, of which we processed and analysed 13,863 thermal power plants and units that exceeded 50 MW with a total active capacity of 4,182 GW (95.8% of global thermal power plant capacity) worldwide. We then built a ‘Best Policies Scenario’ (BPS) on the LUT Energy System Transition modelling tool21 to estimate the development of water demand for each level from the base year of 2015 to 2050 in five-year intervals21. The tool enables us to determine a least-cost scenario of the global energy transition towards a system based on 100% renewable energy and is fully compatible with the sustainability target of IPCC SR1.5. So far, a number of publications have indicated that there is no certainty that the above-mentioned sustainability target will be met in the future27,28,29. By the end of 2018, more than 180 peer-reviewed articles described 100% renewables for 2050 or earlier, as summarized by Hansen et al.30. The intention of this research is to educate on the potential water savings if the large majority of thermal power plants are replaced by renewable energy technologies. To address this concern, in addition to the scenarios incorporated in this study, the IRENA’s Remap203029 scenario was considered. The scenario was applied for 24 countries presented in our database and the values of water withdrawal and water consumption were compared with the estimates based on the BPS for the year 2030 (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 and Supplementary Fig. 1). We present the results for freshwater only and for aggregated water use to indicate the total amount of seawater and freshwater use at the global, regional and country levels. We present an impact analysis on the global–local level for all major rivers in the world carried out in a high temporal and spatial resolution.

Analytical approach

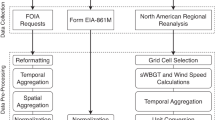

To evaluate the actual water abstractions of thermal power plants for cooling purposes and to address the above-mentioned issues and objectives, we developed a four-step method that follows a bottom-up approach.

As the first step, we identified the location and cooling system type for each power plant using free and easily accessible satellite images (for example, from Google Earth, Bing, Yandex.Maps or other high-resolution products). The methodology of this step is already described and applied10,11. Supplementary Fig. 2 gives visual examples. However, not for all power plants can the cooling technology be determined based on satellite images. To fill these gaps, we developed a statistical method premised on historical data and technological trends (Dataset on thermal power plants section, Methods). Next, we deployed the method of Geographic Information System (GIS) analysis to identify whether sea or freshwater is used for the cooling of each power plant.

For the second step, we calculated the footprint for cooling (focusing on both freshwater withdrawal and consumption) of each power plant taking into account its actual net generation, fuel type, technology and cooling system in 2015.

The third step was to compute the total water footprint on different levels—global, regional, country and river. We compare our results to the values reported by Flörke et al.12 and the GWSP Digital Water Atlas18 (Comparison with GWSP sheet in Supplementary Data 3 and Supplementary Fig. 3). In addition, we compared our estimations of water consumption with the data reported in 2015 by the Energy Information Administration (EIA) for 865 unique power plants located in the United States31, as well as with previous studies conducted by Diehl and Harris32 (Supplementary Table 3). The identification of the cooling system and water used for cooling was compared against individual plant data provided by the EIA for the United States and against individual power plants located in other countries, for which information from the GlobalData database was available. Our method was demonstrated to deliver the correct results in 81% of the cases for the cooling system identification (Supplementary Tables 4 and 5 and Supplementary Note 1) and in 93% of cases for the determination of the water type (Supplementary Tables 6 and 7 and Supplementary Note 2).

Lastly, with a specific identity number assigned to each of the power plants, the model allowed us to trace their specific decommission when reaching the end of their technical life as scheduled by the LUT model21,33. It also accounts for the changes in the operations of the power plants, which originate from the implementation of new renewable energy capacity and the adaptation of the energy system in each of the 145 modelled regions. We evaluated our model by comparing the results of the BPS with the outcomes of the scenario based on the lifetime of power plants1,33. In this research, the latter scenario is referred to as the Lifetime Scenario (LTS). More details on the above-mentioned scenarios and the model construction are provided in Methods.

Current and projected global water abstractions

The current status and the development of water demand on the global and regional levels is shown in Fig. 1. In the base year 2015, the total global water withdrawal (combined freshwater and seawater) for thermal electricity generation was 500 km3 (Fig. 1a), of which freshwater withdrawal constituted 290 km3, or 57.3%. Global water consumption was estimated at 25 km3 (Fig. 1b), of which freshwater consumption accounted for 18 km3 or 72%. Median, minimum and maximum values of the current global water abstractions are presented in Table 1.

Based on the LUT Energy System Transition model and on the BPS. a–c, global water withdrawal from 2015 through 2030 and 2050. The total global water withdrawal decreases from 4.99 × 1011 m3 in 2015 to 1.24 × 1011 m3 in 2030 and 2.45 × 1010 m3 in 2050. d–f, Global water consumption from 2015 through 2030 and 2050. The total global water consumption decreases from 2.47 × 1010 m3 in 2015 to 3.69 × 109 m3 in 2030 and 5.56 × 108 m3 in 2050.

The water consumption for power generation is not evenly distributed globally. In 2015, the top countries in both freshwater-only and total water consumption were China, the United States, India and Russia (Water demand per country sheet in Supplementary Data 3 and Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5). In the same year, China accounted for 31.5% of the global freshwater consumption, consuming almost 6 km3 annually. The United States, with the largest freshwater withdrawals for thermal power generation in the world, extracted 102 km3, which represents 35.7% of all freshwater withdrawals by the power sector globally.

In the case that the BPS is implemented, a rapid decline in both global water withdrawal and consumption can be of benefit during the period from 2015 to 2030, as a consequence of the projected decommissioning of old power plants (Fig. 1a,b,d,e) and replacement by renewable energy technologies that are less water demanding. In 2030, water withdrawal is projected to be reduced by 75.1% compared to 2015 levels. Global water consumption is further mitigated by 85.1% compared to 2015 levels. This tendency continues beyond 2030 to further reduce water withdrawal and consumption.

During the analysed period, 1,797 GW of new gas power plant capacities are scheduled to commission globally, from which 1,365 GW are open cycle units and 432 GW are combined cycle units. For this reason, in 2050, water withdrawals are projected to remain large in the territory from the northeast to the south of China, South Korea, Benelux countries, central regions of Russia and Iran. Similarly, water consumption of power generation facilities is estimated to remain high in the east of China, US Mid-Atlantic, South Korea, Russian Urals region, Great Britain and Ireland. During the transition period from 2015 to 2050, the global water withdrawal is projected to decrease by approximately 95.1%, whereas the consumption is projected to decline by 97.7%.

Power plants’ local impact on river ecosystems

The GIS analysis shows that 55.5% of the global thermal power plant capacity is located within 5 km of the main global rivers and lakes, and is therefore assumed to be freshwater cooled. In addition, 11.1% of the global thermal power plant capacity has an unknown freshwater source. The global thermal power plant capacity located within 20 km from the ocean coastline is assumed to be seawater cooled and in total is 33.4% (Methods, GIS analysis/water source for cooling identification, and Supplementary Fig. 6).

Historically, rivers represent natural borders of neighbouring countries and regions. At the same time, many large rivers cross territories of multiple countries. Hence, in analysing water abstractions from local rivers, we paid special attention to the correct assignment of generation factors of power plants located at specific rivers and, at the same time, the membership to different regions or countries. These plant-specific data were then applied in calculations of water abstractions at the global, regional and country levels.

The outcome of our river analysis highlights that the Ohio River, Yellow River and Mississippi River are the rivers faced with the largest water consumption. Moreover, the Yangtze, Mississippi and Tennessee Rivers experience the highest water withdrawals from the energy sector. Globally, the Yangtze River experiences the largest water withdrawals of about 12 km3 (median value) annually (Supplementary Fig. 7).

The World Wide Fund for Nature released a list of ten global rivers that are most at risk, which includes the Danube34. We used the Danube river as a representative example for a transition analysis of rivers. The water footprint of 63 identified thermal power plants located within a 10 km buffer zone around the Danube corridor (Fig. 2a) was analysed. These power plants were detected in the territories of Germany, Austria, Slovakia, Hungary, Serbia, Romania and Bulgaria. Together, a total capacity of 18.04 GW, which comprised 2.54 GW of coal-fired, 8.08 GW of gas-fired, 1.61 GW of oil-fired and 5.80 GW of nuclear power plants, was identified.

a, Thermal power plants located within 10 km of the Danube river and with a power capacity of at least 50 MW. b,c, Annual changes in freshwater consumption (median values and minimum–maximum (min–max) intervals), both aggregated (b) and by fuel type used in power production (c). d,e, Annual changes in freshwater withdrawal (median values and min–max intervals), both aggregated (d) and by fuel type (e). Panel c highlights a decline in water consumption by nuclear power plants in 2020–2025. This can be explained by the fact that 44.4% of the active nuclear power capacity located at the Danube is scheduled for decommissioning during this period as ‘very old’ assets. These capacities are currently cooled by cooling towers, and thus there is a sudden drop in water consumption during 2020–2025. In contrast, water withdrawals do not follow the same trend (e). The water withdrawals are mostly caused by once-through cooled nuclear power plants (3,226 MW), which are scheduled to be gradually decommissioned by 2050.

Figure 2b–e illustrates the change in water use for power production based on the BPS. In 2015, 6.19 km3 (median value) of water were withdrawn and 0.12 km3 (median value) were consumed for thermal electricity generation, of which 66.5% is related to nuclear power production. In the same year, power plants located in the German territory had the highest water consumption from the Danube (more than 59 million cubic metres, which represent 49% of the aggregated consumption). This high share can be explained by the fact that 97.7% of the analysed power plants located in Germany are equipped with cooling towers, which is the most water consuming cooling technology14. Power plants at the Danube with cooling towers add up to 6.73 GW (37.3%) of capacity. Opposed to that, power plants located in Bulgaria had the highest water withdrawal driven by coal and nuclear generation (more than 2.79 km3, which represents 45% of the total withdrawals).

During the first ten years of the transition period (2015–2025), a strong decrease in water consumption of 73.9% is estimated for the Danube, based on the BPS. A total of 35 thermal power plants are scheduled for decommissioning during this period. The projected decline in water consumption is down to 6.9% in 2040 compared to the 2015 baseline. Water withdrawal does not show the same rapid declining trend. In 2025, cooling still requires 72.9% of the initial water withdrawal, whereas in 2040, 16.0% of the 2015 water withdrawal is still required. This could be explained by the fact that 49% of the overall capacity consists of power plants with once-through cooling systems, which need a comparably high amount of withdrawn water for cooling14.

The simulation projects no water abstraction from the Danube associated with thermal electricity generation by 2050. The corresponding savings in water could be redistributed for other purposes, for example, agricultural irrigation. The ‘Water consumption per river’ and ‘Water withdrawal per river’ sheets in Supplementary Data 3 present the results for 354 rivers globally.

An optimal path towards water and energy sustainability

In choosing a sustainable energy transition scenario for a country or a region, the focus of policymakers should be on both compatibility with IPCC SR1.5 and to ensure better mitigation strategies for energy-based water use. To address this call from the perspective of water conservation and to perform the analytical comparison between the LTS and BPS, we deployed a metric of cumulative difference.

The cumulative difference constitutes the estimated amount of freshwater consumption and withdrawal that could be excluded from thermal power production globally in the case that the BPS is put into practice instead of the implementation of LTS. It is calculated as the disparity between the estimated global freshwater consumption and withdrawal in the LTS and its projected counterpart in the BPS for the same time period. The outcome of the analysis is presented in Fig. 3 for the transition period 2015–2050 at five-year intervals.

a,d, Development of global freshwater withdrawal and consumption in 2015–2050 by fuel type in the LTS. b,e, Development of global freshwater withdrawal and consumption in 2015–2050 by fuel type in the BPS. c,f, Cumulative difference in freshwater withdrawal (c) and cumulative difference in freshwater consumption (f). The numbers in c and f show the difference in water demand savings of the given time compared to those of the previous time interval.

In 2020, the cumulative difference is estimated at 22.7 km3 less global freshwater withdrawal in the case that the LTS is pursued. Beyond 2020 the estimated cumulative difference is reversed: between 2020 and 2050, the BPS allows us to consistently save up to 43.5 km3 of freshwater withdrawn and up to 6.5 km3 of freshwater consumed during each of the five-year periods. Figure 3c–f illustrates a 35-year perspective and shows cumulative savings of 168.5 km3 of freshwater withdrawn and 29.4 km3 consumed compared to those of the LTS from 2015 to 2050. This amount of freshwater ‘saved’ from consumption is pivotal, as this water would not return to the local water system if it evaporates.

Discussion

In our research we addressed the aspect of the water-energy nexus, which is related to the depletion of water resources due to the operation of thermal power plants. By implementing the BPS, we show that the water consumption of the global power plant fleet can be decreased by 97.7% and water withdrawal by 95.1% by the year 2050. The BPS was compared against the LTS and an advantage of the BPS highlighted. The water that is freed in the BPS could be used by aquatic ecosystems or allocated to other purposes, for instance, food production. Thus, the results of our research can potentially help in further studies on global food security to achieve a sustainable water–energy–food nexus35.

The selected BPS represents a least-cost energy-system transition pathway and matches the targets of IPCC SR1.5. In addition, it is in line with leading research on energy transition pathways towards a very high level of sustainability22,24,36,37. The results of this research are premised on a compiled power plant database that contains the location of thermal power plants with a high accuracy. Coupled with high-resolution maps, this contributes to the precision of the applied estimates of water use for cooling purposes. Using this data, we detected the rivers most affected by the water footprint of thermal power plants worldwide and highlighted for all rivers how the water stress can be reduced under the BPS up to 2050.

The results of our research deviate from the water withdrawal values reported by Flörke et al.12 and presented in the GWSP Digital Water Atlas18. The deviations from the GWSP data can be explained by the consideration of seawater and freshwater use in this research, as well as the allocation of cooling technologies for individual power plants. Our results could potentially be compared with the upcoming Water Resources Institute global water withdrawals and consumption research, in which there is a separation of seawater and freshwater demand and a detailed analysis of power plant cooling technologies10.

In conclusion, we provide an extensive analysis of the water use of power plants that supports global and regional policy-making, and hence contribute to accomplish water security on a global–local level, which addresses the UN Sustainable Development Goal 6 ‘Ensure access to water and sanitation for all’38. Taking the BPS as an example of a possible pathway for the global energy sector, we show that the depletion of water resources caused by the water–energy nexus can be mitigated by transitioning to an electricity supply based on renewable energy.

Methods

Dataset on thermal power plants

The main source of the power plant data of this study is the GlobalData dataset26. Taking this as a starting point, the data was cross-referenced and curated with the information gathered from other datasets39,40,41,42 by Farfan and Breyer33 according to the SeaDataNet QC Manual43. However, the analysis by Farfan and Breyer33 did not include the spatially highly resolved locations of the power plants, which is part of this study.

The data on power plants was then filtered to contain only thermal electricity generation, defined for this study as nuclear and fossil-fuelled (coal, gas and oil) power plants. This subset was further filtered by capacity to include only active power plant units that exceed 50 MW. The choice of this low boundary of capacity is because power plant units of lower capacity include microgeneration and cannot be identified using aerial imagery, which is the main method of identification of power plants’ location in our research. For this set-up, 13,863 units with a total active capacity of 4,182 GW are present globally for further analysis, which represents 66.3% of the total global power plant capacity, and 95.8% of the global thermal capacities in 2015. Supplementary Note 3 gives more information regarding the technologies that were left out of the scope of the study.

We manually determined the exact location and cooling system type using aerial imagery through Google Earth, Bing and Yandex.Maps, following the instructions given by the US Geological Survey11. We considered five types of cooling systems: wet cooling towers (which include natural-draft towers and mechanical-draft towers), dry cooling systems (known also as air-cooled condensers), inlet cooling systems of gas power plants and the so-called surface-water cooling systems, which have two subcategories—once-through cooling systems and recirculating cooling-pond systems. More information concerning the applied approach of using satellite imagery for cooling systems identification is given in Supplementary Note 4.

To fill in the gaps for the cooling technology, several steps were performed. First, for each type of fuel (nuclear, coal, gas and oil) and for specific countries we identified the historically most common combination of generator type and cooling technology using a simple statistical analysis. If this combination could not be determined for a specific power plant, it was assigned the most common cooling technology of power generators for the given country.

For countries with missing values of the cooling technology, a sensitivity analysis was performed to analyse the effect of the assignment of different combinations of generator type and cooling technology on the water demand (Supplementary Note 5, Supplementary Table 8 and Supplementary Fig. 8). The sensitivity values at country level together with the probabilities of these values are presented in the sheets in Supplementary Data 3 for both consumption (‘Sensitivity of country cons.’ sheet) and withdrawal (‘Sensitivity of country withd.’ sheet).

The results of the identification of the cooling technology were compared against data for individual power plants presented in the GlobalData dataset (Supplementary Table 4). In addition, we compared our results with information reported by the EIA for the United States44. As depicted in Supplementary Table 5 and Supplementary Data 2, our method of cooling system identification was demonstrated to deliver the correct results in 81% of the cases.

Analysis of water footprint of power plants

In this research we deployed a bottom-up approach. We calculated the water footprint of each power plant separately for water consumption and water withdrawal using equation (1):

where the active capacity of installed power plants is given in megawatts, water use intensity (WUI) in m3 MW–1 h–1 and full load hours of power generation in hours.

The difference between the calculation of the water footprint for water consumption and water withdrawal is in the WUI in equation (1). The values for the WUI were derived based on empirical records of water use by power plants and reported by Macknick et al.14. Supplementary Table 9 contains the values of WUI that were applied for this research. Some scholars32,45 raised the problem that the water consumption factors of once-through cooling systems are underestimated because forced evaporation downstream of the discharge point was excluded. Forced evaporation depends on various factors (site-specific average natural water temperature, average wind speed and the water surface area over which heat is dissipated11). Consequently, it has to be calculated for every specific case, which was out of scope of our research. In addition, the WUI values reported by Macknick et al. currently are widely applied by respected institutions and research8,10. In this stage, we grouped oil- and gas-fired power plants into one category as no oil plant data are available. The same method was used in previous research papers10,46. However, we acknowledge the higher water dependency of oil power plants in comparison to that of gas plants.

The first two values in equation (1) (active capacity and full load hours) characterize the actual net generation of the given power plant. Full load hours for the year 2015 were obtained from International Energy Agency (IEA) Statistics47 and were also used by Bogdanov et al.21 and assigned to each power plant according to the fuel type and location (region in the global LUT model matched with the respective country according to the IEA Statistics) presented in the database. Differentiating the full load hours based on the location and fuel type adds to the accuracy of the study when the full load hours of individual power plants are not accessible. However, owing to the lack of information concerning the actual generation data of individual power plants, the average values were used in the calculations. One differentiation not considered in this study is the potentially different average operating hours for the categories of gas steam and combined cycle, which in the present study are considered as equal. As shown in Supplementary Table 9, the withdrawal and consumption coefficients are significantly higher for gas steam than for combined cycle. However, owing to the unavailability of accurate data at a global level, we acknowledge that this as a limitation in the present study. A large variation in the actual values of the full load hours of power plants of a given fuel in a given region might impact the correctness of the water demand estimations. Using the openly available data provided by the EIA for the United States, we calculated the coefficient of variation of annual hours in service for thermal power plants31,44 (Supplementary Table 10). The results highlight that the average coefficient of variation of the annual hours in service of coal and nuclear power plants is low (4%). Thus, the use of average full load hours for coal and nuclear power plants will not significantly affect the correctness of water demand estimations. In the case of gas and oil power plants, the average coefficient of variation is higher—about 19%. Therefore, the use of average full load hours for gas and oil power plants might impact the accuracy of the results at the plant level. However, this plant-to-plant difference in hours in service might not significantly affect the country-level estimates of water use as the value reported by the EIA48 for the total net electricity generation of thermal power plants in 2015 was only 1.3% higher than the corresponding value provided by the LUT model. Using the same dataset provided by the EIA, we calculated the average hours in service of power plants that utilize the same cooling technology. As depicted in Supplementary Table 11, the difference in hours in service of once-through cooling systems and cooling towers is, on average, 2.2% and thus considered small. Therefore, based on the results presented in Supplementary Tables 10 and 11, the use of the same value of full load hours for all types of cooling of a given type of power plant in a given region is appropriate.

At subsequent stages, we calculated the total water footprint and the freshwater footprint with different scopes: at the global level, for the 145 regions of the LUT model, for 148 countries and for major rivers. Results were obtained for the LTS and BPS scenarios for the period 2015–2050. The ‘Water demand per region’ sheet in Supplementary Data 3 gives more information on water demand development for each region, based on the BPS.

GIS analysis and water source for cooling identification

To link the thermal power plants with water bodies, we deployed a method of GIS analysis based on the Global Self-consistent, Hierarchical, High-resolution Geography Database (GSHHG)49 as a source of a high-resolution geography dataset that includes global coastlines, lakes, rivers and political borders.

A literature review showed that there is a wide range of assumptions concerning seawater use for cooling purposes of power plants. These assumptions are based on the relative position of the given power unit and its distance to the closest coastline, starting from 5 km and up to 100 km (refs 15,50). There are reported cases of water transported up to a distance of 70 km in Phoenix, Arizona51. These distances may vary for different locations depending on different factors (as discussed by Behrens et al.1). Thus, we assumed that all the thermal power plants located within 20 km of a coastline use seawater for cooling purposes as recommended in a study by Greenpeace13.

The results of the GIS analysis on seawater cooling highlight the strong alignment of the derived results of this research with the reported data on seawater cooling in the Middle East and North Africa region with a deviation of less than 5% (ref. 17). Then, we also took into account reported numbers stating that 50% of the coal power plants in China and 85% of those in India located within 20 km of the coastline use seawater for their cooling13. The analysis revealed for India that 85% of the power plants are located within 7.88 km of the coastline. Thus, we labelled all the thermal power plants in India located within a distance of 7.88 km from the coastline as seawater cooled. In the case of China, 50% of all the thermal power plants located within 20 km of the coastline are even within 0.49 km. Therefore, all the thermal power plants in China located within 0.49 km from the coastline were assigned as seawater cooled. All other thermal power plants were assumed to use freshwater for cooling purposes. This analysis was conducted only for India and China because of the lack of similar information concerning other countries.

The applied assumption of 20 km might lead to an underestimation of the freshwater use in the world13. To assess the deviation of the freshwater demand that results from the choice of the seawater cooling buffer zone, we performed a sensitivity analysis (Supplementary Table 12). The results of the analysis show that reducing the sea cooling range from 20 km to 4 km results in a smooth increase of global freshwater consumption and withdrawal. For instance, if the sea cooling range is reduced to 12 km, the difference in freshwater consumption and withdrawal is below 2% compared to the 20 km assumption. Assuming a sea cooling range of 2 km, a difference of 12.3% for freshwater consumption and 8.6% for freshwater withdrawal is estimated, compared to the assumed 20 km for this study. The difference can be explained by the fact that thermal power plants tend to be located closer to the coastline (Supplementary Figs. 9 and 10).

The power plants were assumed to have a direct freshwater source for cooling if they are located within 5 km of rivers and lakes. We used the GSHHG database for the GIS analysis as it provides the location of about 25,960 rivers worldwide in high resolution. Facilities with an intake or discharge of cooling water to a smaller stream, or those that use groundwater, cannot be matched using GIS analysis. In our research, it was not possible to determine with certainty the exact source of water of 9.9% of the total active capacity presented in our filtered database. Further information provided by electricity generation companies proved that those power plants use ground water for their cooling purposes (an example is given in Groves et al.52), so these results were added to the freshwater consumption and water withdrawal numbers.

In more than half of the reported cases concerning cooling technology presented in the GlobalData dataset, the type of water used for cooling purposes is specified (seawater or water from rivers or lakes). We used the reported data for individual power plants to compare our results for the identification of the water type (Supplementary Table 6). Moreover, we used data provided by the EIA for the United States44 to compare our results for the identification of the water type. As depicted in Supplementary Table 7 and Supplementary Data 2, the proposed method shows a high accuracy for the determination of the water type (93% of cases demonstrate a correctly identified water type), which clearly indicates that it can be used for regional and global studies. However, we acknowledge that to obtain a higher accuracy for the results at the plant level, it is necessary to consider data directly reported by power generation companies for each specific power plant unit.

Transition scenarios

We performed our analysis of the water footprint development in five-year time steps in a full hourly resolution, focusing on the transition period for the years from 2015 to 2050. Two scenarios were considered: LTS and BPS.

The main idea of the LTS is that the stock of thermal power plants is assumed to operate until the point of decommissioning. We follow the reasoning of Farfan and Breyer33, who calculated the expected year of decommissioning as the reported year of commissioning of a power plant plus the average technical lifetime of the power plant by fuel type. Thus, we assumed that the average technical lifetime for gas- and oil-fired power plants is 34 years, and for coal-fired and nuclear power plants 40 years53. However, the database used contains power plants that were active in 2015 that should have been decommissioned before that year (these plants were highlighted as ‘very old’). In addition, those power plants in the database for which the commissioning year is unknown were marked as power plants with ‘unknown year’. The unknown year category represents 123.92 GW, or 3.0%, of the total thermal capacity. The very old power plants that are still operating represent 748.87 GW, or 17.9%, of the thermal power plant capacity. We assumed that the above-mentioned two categories of power plants are gradually decommissioned between 2015 and 2025, 10% of their initial capacity per year. The BPS was constructed on the basis of the LUT Energy System Transition model21. According to this model, the operation of the power sector is cost optimized and the full load hours of coal-, gas- and oil-fired power plants are a part of the optimization and can decrease or cease during the transition period, as shown in the data presented by Bogdanov et al.21. Opposed to that, the specific utilization of nuclear power plants does not allow a change of the baseload over time due to security issues, so the continuous utilization of the existing capacity until the end of its technical lifetime was assumed (except for Germany, where partly an earlier decommissioning is forced by law). Hence, the outcome of the applied scenario is a time series of full load hours of power generation facilities for each of the 145 regions. The model tolerates the role of gas power plants during the transition period due to lower greenhouse gas emissions and, in particular, the possibility to substitute the currently used natural gas by biomethane or power-to-gas in these plants at later time periods. Thereby, according to the outcomes of the applied scenario, 1,797 GW of gas-fired capacities will be installed globally from 2015 to 2050, whereas 2,077 GW are still active in 2050 and used by a global average of 483 full load hours. We determined and assigned to the new capacities the most common gas generator type during the past 15 years for each of the 145 regions. The cooling technology was assigned as indicated in the Dataset on thermal power plants section. The changes in the water footprint of new commissioned plants as well as of the existing operating gas power plants were calculated in the same way as for coal- and oil-fired power plants using the full load hours generated by the LUT Energy System Transition model. We followed the logic of the power plant decommissioning process described in the LTS.

Supplementary Note 6 contains the equations that underlie the calculation of water demand of power plants in the LTS and BPS.

Analysis of water footprint of power plants on global rivers

For the river analysis we required a river database that also contained names of rivers. Commonly, the rivers are given a certain identity number rather than their respective names, and thus we chose to use the river database from Natural Earth54.

Initially, the database contained 1,454 rivers and river sections. For rivers with missing or misspelled names, these were investigated and corrected manually. Separate sections of rivers that belong together were merged. Using GIS analysis, we identified rivers with power plants located within 5 km of the river’s corridor. As a result, we obtained 354 unique rivers for further analysis.

We calculated the water consumption and water withdrawal of power plants separately for each of these 354 rivers, as well as the projected values for the period 2015–2050 with five-year intervals using the baseline of the BPS. To make the results of this work useful to local policy makers, we assigned to each of the given rivers the corresponding continent and ocean of discharge and the country with the highest impact on its flow.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from GlobalData26, but restrictions apply to the availability, which was used under license for this study. The database encompasses over 170 fields of information, which include the names of power generators, owners, operators, generator manufacturers and so on. An extract of the extensive list of thermal power plants that exceed 50 MW, which contains fuel type, country, active capacity, generation type, location and type of cooling technology, is available as Supplementary Data 1. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

Example Matlab scripts used in the production of this analysis are available at https://github.com/WaterEnergyWork/FreshwaterDemand.git

Change history

20 December 2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-024-01700-w

References

Behrens, P., van Vliet, M. T. H., Nanninga, T., Walsh, B. & Rodrigues, J. F. D. Climate change and the vulnerability of electricity generation to water stress in the European Union. Nat. Energy 2, 17114 (2017).

Ganguli, P., Kumar, D. & Ganguly, A. R. US power production at risk from water stress in a changing climate. Sci. Rep. 7, 11983 (2017).

Water Energy Nexus WEO-2016 Special Report (International Energy Agency, 2016); https://doi.org/10.1021/es903811p

van Vliet, M. T. H. et al. Vulnerability of US and European electricity supply to climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 2, 676–681 (2012).

Roehrkasten, S., Schaeuble, D. & Helgenberger, S. Secure and Sustainable Power Generation in a Water-Constrained World (Institute for Advanced Sustainability Studies, 2015).

McDermott, G. & Nilsen, O. Electricity prices, river temperatures, and cooling water scarcity. Land Econ. 90, 131–148 (2014).

Boogert, A. & Dupont, D. The nature of supply side effects on electricity prices: the impact of water temperature. Econ. Lett. 88, 121–125 (2005).

Spang, E. S., Moomaw, W. R., Gallagher, K. S., Kirshen, P. H. & Marks, D. H. The water consumption of energy production: an international comparison. Environ. Res. Lett. 9, 105002 (2014).

Kenny, J. F. et al. Estimated Use of Water in the United States in 2005 Circular 1344 (US Geological Survey, 2009); https://doi.org/10.3133/cir1405

Luo, T., Krishnaswami, A. & Li, X. A Methodology to Estimate Water Demand for Thermal Power Plants in Data-Scarce Regions using Satellite Images Technical Note (World Research Institute, 2018); https://www.wri.org/publication/methodology-estimate-water-demand-thermal-power-plants-data-scarce-regions

Diehl, T. H., Harris, M. A., Murphy, J. C., Hutson, S. S. & Ladd, D. E. Methods for Estimating Water Consumption for Thermoelectric Power Plants in the United States Scientific Investigations Report 2013–5188 (US Geological Survey, 2013); https://doi.org/10.3133/sir20135188

Flörke, M. et al. Domestic and industrial water uses of the past 60 years as a mirror of socio-economic development: a global simulation study. Glob. Environ. Change 23, 144–156 (2013).

Biesheuvel, A., Witteveen+Bos, Cheng, I., Liu, X. & Greenpeace International. Methods and Results Report: Modelling Global Water Demand for Coal Based Power Generation (Witteveen + Boss, Greenpeace, 2016).

Macknick, J., Newmark, R., Heath, G. & Hallett, K. C. Operational water consumption and withdrawal factors for electricity generating technologies: a review of existing literature. Environ. Res. Lett. 7, 045802 (2012).

van Vliet, M. T. H., Wiberg, D., Leduc, S. & Riahi, K. Power-generation system vulnerability and adaptation to changes in climate and water resources. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 375–380 (2016).

Vassolo, S. & Döll, P. Global-scale gridded estimates of thermoelectric power and manufacturing water use. Water Resour. Res. 41, 1–11 (2005).

Siddiqi, A. & Anadon, L. D. The water–energy nexus in Middle East and North Africa. Energy Policy 39, 4529–4540 (2011).

GWSP Global Water System Project Digital Water Atlas (Global Water System Project, 2008); http://atlas.gwsp.org/

Maulbetsch, J. & Stallings, J. Evaluating the economics of alternative cooling technologies. Power Eng. 116, 120–128 (2012).

Masson-Delmotte et al. Global Warming of 1.5 °C Special Report (IPCC, 2018).

Bogdanov, D. et al. Radical transformation pathway towards sustainable electricity via evolutionary steps. Nat. Commun. 10, 1077 (2019).

Jacobson, M. Z. et al. Matching demand with supply at low cost in 139 countries among 20 world regions with 100% intermittent wind, water, and sunlight (WWS) for all purposes. Renew. Energy 123, 236–248 (2018).

Creutzig, F. et al. The underestimated potential of solar energy to mitigate climate change. Nat. Energy 2, 17140 (2017).

Sgouridis, S., Csala, D. & Bardi, U. The sower’s way: quantifying the narrowing net-energy pathways to a global energy transition. Environ. Res. Lett. 11, 094009 (2016).

Teske, S. Achieving the Paris Climate Agreement Goals (Springer International, 2019).

GlobalData Power (GlobalData Ltd, accessed 20 November 2015); http://power.globaldata.com/Home.aspx

Tracking Clean Energy Progress 2017 (International Energy Agency, 2017); https://www.iea.org/etp/tracking2017/

World Nuclear Performance Report (World Nuclear Association, 2016).

Global Energy Transformation: A Roadmap to 2050 (IRENA, 2019); https://www.irena.org/-/media/Files/IRENA/Agency/Publication/2019/Apr/IRENA_Global_Energy_Transformation_2019.pdf

Hansen, K., Breyer, C. & Lund, H. Status and perspectives on 100% renewable energy systems. Energy 175, 471–480 (2019).

Form EIA-923 Detailed Data with Previous Form Data (EIA-906/920) (US Energy Information Administration, accessed 29 June 2019); https://www.eia.gov/electricity/data/eia923/

Diehl, T. H. & Harris, M. A. Withdrawal and Consumption of Water by Thermoelectric Power Plants in the United States, 2010 Science Investigation Report 2014-5184 (US Geological Survey, 2014); https://doi.org/10.3133/sir20145184

Farfan, J. & Breyer, C. Structural changes of global power generation capacity towards sustainability and the risk of stranded investments supported by a sustainability indicator. J. Clean. Prod. 141, 370–384 (2017).

Wong, C., Williams, C., Pittock, J., Collier, U. & Schelle, P. World’s Top 10 Rivers at Risk (WWF, 2007); http://d2ouvy59p0dg6k.cloudfront.net/downloads/worldstop10riversatriskfinalmarch13_1.pdf

Biggs, E. M. et al. Sustainable development and the water–energy–food nexus: a perspective on livelihoods. Environ. Sci. Policy 54, 389–397 (2015).

Greenpeace, GWEC & SolarPower Europe. Energy [R]evolution: A Sustainable World Energy Outlook 2015 (Greenpeace International, 2015).

Brown, T. W. et al. Response to ‘Burden of proof: A comprehensive review of the feasibility of 100% renewable-electricity systems’. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 92, 834–847 (2018).

Clean Water and Sanitation: Why It Matters (United Nations, 2016); https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/6_Why-it-Matters_Sanitation_2p.pdf

World Electric Power Plants Database (S&P Global Platts, 2016).

Renewable Energy Capacity Statistics 2015 (IRENA, 2015).

Lehner, B. et al. High-resolution mapping of the world’s reservoirs and dams for sustainable river-flow management. Front. Ecol. Environ. 9, 494–502 (2011).

Gerlach, A., Werner, C., Gerlach, A., Breyer, C. & Orlandi, S. In Proc. of the 31st European Photovoltaic Solar Energy Conference (eds Rink, S., Helm, P & Taylor, N.) 2965–2973 (WIP Renewable Energies, 2015).

Schaap, D. M. A. & Lowry, R. K. SeaDataNet—Pan-European infrastructure for ocean and marine data management. Int. J. Digit. Earth 3, 50–69 (2010).

Form EIA-860 detailed data with previous form data (EIA-860A/860B) (Energy Information Administration, accessed 29 June 2019); https://www.eia.gov/electricity/data/eia860/

Morton, V. & Echeverri, D. P. Electric Power Plant Water Use in North Carolina: Forced Evaporation and Emission Controls. MSc Thesis, Duke Univ. (2010).

Feeley, T. J. et al. Water: a critical resource in the thermoelectric power industry. Energy 33, 1–11 (2008).

Statistics. Global Energy Data at your Fingertips (International Energy Agency, 2018).

Electric Power Monthly (US Energy Information Administration, accessed 29 June 2019); https://www.eia.gov/electricity/monthly/epm_table_grapher.php?t=epmt_1_01

Wessel, P. & Smith, W. H. F. A global, self-consistent, hierarchical, high-resolution shoreline database. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 101, 8741–8743 (1996).

Zhou, Y. & Tol, R. S. J. Evaluating the costs of desalination and water transport. Water Resour. Res. 41, 1–10 (2005).

Cooling Power Plants (World Nuclear Association, accessed 1 November 2017); http://www.world-nuclear.org/information-library/current-and-future-generation/cooling-power-plants.aspx

Groves, J., Krankkala, T. & Nigent, G. Afton combined cycle with hybrid cooling. Power Engineering 114, 56–60 (2010).

Farfan, J. & Breyer, C. Aging of European power plant infrastructure as an opportunity to evolve towards sustainability. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 42, 18081–18091 (2017).

Rivers + lake centerlines (Natural Earth, 2016); https://www.naturalearthdata.com/downloads/50m-physical-vectors/50m-rivers-lake-centerlines/

Acknowledgements

The authors thank M. Flörke for helpful discussions concerning earlier versions of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.L. designed the study and performed the analysis, collected data on cooling technology and water use and drafted the manuscript. J.F. collected the data on existing power plants globally, and assisted with the methodology development and the results analysis. U.C. assisted with the methodology development and literature review. C.L. assisted with the sensitivity analysis and gave support for the paper writing. C.B. assisted with the analysis and initiated, supervised, reviewed and coordinated the work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–10, Tables 1–12, Supplementary Notes 1–6 and refs. 1–11.

Supplementary Data 1

Power plant database, estimated water demand of individual power plants, projected water demand in 2020–2050 for the Lifetime and Best Policies Scenarios.

Supplementary Data 2

Comparison of identification of cooling technology and water type with the information reported in the US EIA database.

Supplementary Data 3

Water footprint of thermal power plants on regional, country and river levels; results of the sensitivity analysis; results of the comparison of the estimated water demand with the values presented in the GWSP Digital Water Atlas.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lohrmann, A., Farfan, J., Caldera, U. et al. Global scenarios for significant water use reduction in thermal power plants based on cooling water demand estimation using satellite imagery. Nat Energy 4, 1040–1048 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-019-0501-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-019-0501-4

This article is cited by

-

Evaluating renewable energy adoption in G7 countries: a TOPSIS-based multi-criteria decision analysis

Discover Energy (2025)

-

Global advancement of solar photovoltaic thermal technologies integrated with membrane distillation systems: a comprehensive review

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2025)

-

Gridded global dataset of industrial water use predicted using the Random Forest

Scientific Data (2024)

-

Current and future global water scarcity intensifies when accounting for surface water quality

Nature Climate Change (2024)

-

A framework to assess multi-hazard physical climate risk for power generation projects from publicly-accessible sources

Communications Earth & Environment (2023)