Abstract

Bedrock composition, in particular the proportion of carbonate, can influence the dissolved inorganic carbon concentration and also the carbonate chemistry of rivers, but its effects on the nitrogen cycle in rivers are usually overlooked. Here we present geochemical composition measurements of rivers across the Pearl River Basin in China that show that dissolved organic nitrogen (DON) is positively correlated with dissolved inorganic nitrogen and follows the variation in solar radiation in the carbonate-dominated region during the wet season, but not in the non-carbonate-dominated region. In situ incubations show that organic nitrogen production is strengthened in the regions with high dissolved inorganic carbon and high temperature and solar radiation. DON zonation in the dry season is not obvious owing to the limitation of low temperature on nitrogen assimilation. We also report a similar DON contrast in carbonate-dominated and non-carbonate-dominated regions in Malang in Indonesia. Furthermore, from an analysis of global published data, we find that a modified Michaelis–Menten model incorporating carbon limitation provides a much better fit to the global latitudinal distribution of DON globally. Hence, we propose that carbonate weathering enhancement of organic nitrogen production occurs ubiquitously.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Dissolved inorganic nitrogen (DIN) is one of the most ubiquitous pollutants in aquatic systems, where excess DIN can lead to eutrophication1 and hypoxia2 in surface water bodies. N uptake or assimilation is a process that utilizes DIN and synthesizes it into organic N. In this way, DIN is temporarily retained and removed through the burial of organic compounds in sediments. N assimilation is found to be more vital in removing DIN than denitrification3,4,5 in various river networks. However, robust uptake can become problematic by boosting aquatic primary production and increasing the potential of eutrophication under excessive nutrients loading6,7,8.

Various drivers are reported to influence N uptake in surface water bodies, such as land use9, solar radiation10, phytoplankton species11, temperature12 and so on. However, when river water flows across a watershed with different geological backgrounds and formations, processes such as chemical weathering strongly influence the physical and chemical properties of water but are overlooked13. Globally, 38.5% of the Earth’s land surface consists of silicate rocks, while only 15% are carbonate rocks14. Both carbonate and silicate weathering are reported to participate in the carbon (C) cycle and can act as C sinks15,16,17. Usually, the N is coupled in C cycles, serving as the nutrient, but how C modifies the N cycle in aquatic systems has been long overlooked. For example, nitrate (\({{\rm{NO}}}_{3}^{-}\)) was linked to the autochthonous dissolved organic carbon (DOC) production in a small carbonate-dominated basin18, but there is a lack of research compared with the non-carbonate-dominated region. In addition, acting as the C source, dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) actively participates in primary production, which in turn may affect the N assimilation. Carbonate weathering increases the river water pH and DIC19, which potentially impacts C- and N-related biotic activities20. Therefore, conducting large-scale investigations across various geological backgrounds is crucial for providing a more comprehensive understanding of the geological processes, such as the influences of carbonate weathering on N transformation, and addressing the knowledge gap.

The Pearl River Basin (PRB) is the second largest catchment in terms of discharge in China21, with an area of over 4.5 × 105 km2. The lithologic composition of the PRB varies considerably, where carbonate rocks account for 44% of the total area in the western region, while the proportion is comparably low (8%) in the eastern region (Fig. 1). Here, we conducted field campaigns across the PRB to evaluate the role of the geological background in controlling N transformations, especially the N assimilatory uptake influenced by DIC. Field incubations were conducted to provide validation for field observations and interpretations. Global datasets on riverine DIC and organic N were collected, and an additional field sampling in Malang, Indonesia, with similar geological settings was conducted to further explore whether our field observations and findings in the PRB are a global phenomenon. This study emphasizes the importance of geologic composition and control of N uptake and organic N variation in river networks.

a, Geological map47 and sampling sites of the PRB. b, The distribution of DIC concentration in the PRB. The two-sided Mann–Whitney test is applied to evaluate the differences, where P < 0.01 is considered highly significant, P < 0.05 is considered significant and P values ≥0.05 indicate no statistical significance. NBP, Nan-bei Pan River Basin; YJ, Yujiang River Basin; HL, Hongliu River Basin; XJ, Xijiang River Basin; PRD, Pearl River Delta; BJ, Beijiang River Basin; DJ, Dongjiang River Basin. The dotted black line in b is the median value of DIC for each sub-basin.

Characteristics of riverine dissolved N species

Through basin-scale field sampling in both the wet and the dry seasons—similar to many water bodies globally22,23,24,25—\({{\rm{NO}}}_{3}^{-}\) is found to be the dominant species of DIN across the PRB, accounting for 96.6 ± 8% (mean ± s.e.m.) in the wet season and 83.9 ± 14% in the dry season. In addition, dissolved organic nitrogen (DON) accounts for 57.9 ± 19% and 28.8 ± 16% of total dissolved nitrogen (TDN) in the wet and dry seasons, respectively. Both \({{\rm{NO}}}_{3}^{-}\) and DON are lower in the dry season than in the wet season (Fig. 2), which is owing to the decreased terrestrial N input in the dry season evidenced by the 15\({{\rm{N}}\text{-}{\rm{NO}}}_{3}^{-}\) and 18\({{\rm{O}}\text{-}{\rm{NO}}}_{3}^{-}\) isotopes. During the wet season, the major source of \({{\rm{NO}}}_{3}^{-}\) is soil N. However, \({\updelta }^{15}{\rm{N}}\text{-}{{\rm{NO}}}_{3}^{-}\) is isotopically heavier during the dry season (5.5 ± 1% in the wet season versus 9.7 ± 3% in the dry season), which indicates a shift in the N source from soil N towards the groundwater, manure or sewage (dry season groundwater \({\updelta }^{15}{\rm{N}}\text{-}{{\rm{NO}}}_{3}^{-}\) of 18.1 ± 10%) (Extended Data Fig. 1). As the total manure application in the PRB across the year is very low (median of 8.5%) compared with the total N fertilizer input26, the major influence should be attributed to sewage and groundwater in the dry season. Meanwhile, the decrease in temperature could be another influencing factor of the temporal variation (Supplementary Fig. 1). Low temperature in the dry season (16.8 ± 3 °C in the dry season versus 28.2 ± 4 °C in the wet season) can inhibit the microbial metabolic rate27 and decrease the production of \({{\rm{NO}}}_{3}^{-}\) via nitrification. This is supported by the comparatively high \({\updelta }^{15}{\rm{N}}\text{-}{{\rm{NO}}}_{3}^{-}\) and \({{\rm{NH}}}_{4}^{+}\) of river water in the dry season (wet season median of 0.9 μmol l−1 versus dry season median of 4.3 μmol l−1), because the microbial nitrification preferentially uses substrates with a lighter isotope (14\({\rm{N}}{{\rm{H}}}_{4}^{+}\)), thereby decreasing the relative abundance of 15N in \({{\rm{NO}}}_{3}^{-}\) (ref. 28). In addition, the optimal phytoplankton growth temperature was reported to be 23–27 °C in the Pearl River Estuary29. The lower temperature and less solar radiation in the dry season compared with the wet season inhibit ecosystem metabolism, including photosynthetic activities, which lead to less DON generation.

a,b, The concentration of \({{\rm{NO}}}_{3}^{-}\) (a) and DON (b) during the wet season and the dry season. The map was developed using Advanced Spaceborne Thermal Emission and Reflection Radiometer Global Digital Elevation Model V003 data from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. The dotted black line in the violin plot is the median value.

Spatially, among all sampling locations, the highest \({{\rm{NO}}}_{3}^{-}\) concentration is observed in the source region (Nan-bei Pan River Basin (NBP)) (Fig. 2). On one hand, the streamflow consists of a higher proportion of groundwater with high \({{\rm{NO}}}_{3}^{-}\) concentration (groundwater median of 195.0 μmol l−1 versus river median of 68.2 μmol l−1) compared with other regions. On the other hand, NBP has the highest ratio of cropland and a comparatively low forest proportion (Supplementary Fig. 2a), suggesting a higher agricultural N input and a lower \({{\rm{NO}}}_{3}^{-}\) interception by forests. The elevated \({{\rm{NO}}}_{3}^{-}\) concentration in the Pearl River Delta (PRD) region and downstream of the Dongjiang River Basin (DJ) during both the wet and the dry seasons can be largely attributed to the substantial anthropogenic inputs of N from megacities, where the 15\({\rm{N}}\text{-}{\rm{NO}}_{3}^{-}\) in these highly urbanized regions is higher than the mean value of the PRB (dry season PRD of 10.4 ± 3%, dry season DJ of 10.3 ± 3% versus dry season PRB of 9.7 ± 3% and wet season PRD of 6.1 ± 0.8% versus PRB of 5.5 ± 1%). The \({{\rm{NO}}}_{3}^{-}\) concentrations in sewage collected from wastewater treatment plants are also high (mean of 427.9 ± 143 μmol l−1 and median of 395.9 μmol l−1), and the high rate of wastewater discharge30 (Supplementary Fig. 2b) further exacerbates the riverine \({{\rm{NO}}}_{3}^{-}\) levels. The riverine \({{\rm{NO}}}_{3}^{-}\) distribution agreed well with a previous 30-yr study31, which found that NBP and PRD are among the highest and most increased net anthropogenic N inputs across the sub-basins, confirming that the \({{\rm{NO}}}_{3}^{-}\) zonation is long-lasting.

Carbonate weathering facilitates organic N formation

Across the PRB, the DIC shows a decreasing trend from the regions mainly covered by carbonate rocks (hereafter referred to as the carbonate-dominant region) to the region mainly covered by silicate and other rocks (hereafter referred to as the non-carbonate-dominated region) (Fig. 1b). This is because the weathering of carbonate rocks occurs at a higher rate than silicate rocks and subsequently releases more DIC into river water14. The DON:\({{\rm{NO}}}_{3}^{-}\) ratio is high in the carbonate-dominant region and low in the non-carbonate-dominated region (especially in the DJ and Beijiang River Basin (BJ)) during the wet season (DON:\({{\rm{NO}}}_{3}^{-}\) ratio median of the carbonate-dominant region of 2.0 versus non-carbonate-dominated region of 0.8) (Extended Data Fig. 2). However, the dissimilarity of the DON:\({{\rm{NO}}}_{3}^{-}\) ratio in the two zones is not obvious during the dry season (Extended Data Fig. 2). Meanwhile, DON had a statistically significant positive correlation with \({{\rm{NO}}}_{3}^{-}\) (r2 = 0.50, P < 0.01) (Fig. 3) in the carbonate-dominant region during the wet season, but this correlation is hardly observed in the non-carbonate-dominated region (r2 = 0.09, P < 0.01). The strong relationship between DON and \({{\rm{NO}}}_{3}^{-}\) in the carbonate-dominated region can be attributed either to the same allochthonous source or to autochthonous transformation, such as mineralization and \({{\rm{NO}}}_{3}^{-}\) uptake.

a,b, The \({\rm{DON}}\text{--}{{\rm{NO}}}_{3}^{-}\) relationship in the carbonate-dominated (a) and the non-carbonate-dominated (b) regions. The solid lines indicate the linear regression fits, and the shaded areas are 95% confidence bands, the green and brown dots represent the data points in wet and dry seasons, respectively, and the dashed lines represent the 1:1 line of DON and NO3−. c,d, The zonation of DON, solar radiation48 and calculated growth rate in the wet (c) and dry (d) seasons, and the results of the Pearson correlation analysis are indicated by lines. In c and d, the green lines indicate the solar radiation (W m−2), the purple lines indicate the growth rate (d−1), the coloured boxes indicate the 25–75% quartiles of the DON concentration using the overall data, the black dots indicate the means, the horizontal black line inside the boxes indicate the median values, the vertical lines above and below the boxes indicate the 1.5 interquartile range (IQR) and the purple and green dots indicate the data points.

The \({{\rm{NO}}}_{3}^{-}\) uptake was found to be responsible for the distribution of DON in the carbonate-dominated region, demonstrated by the fact that DON distribution is strongly controlled by solar radiation in the carbonate-dominated region in the wet season (Fig. 3). Moreover, runoff (simulated using the Soil Conservation Service curve number (SCS-CN) method32,33; Supplementary Text 1) shows positive but weak effects on riverine DON and \({{\rm{NO}}}_{3}^{-}\) during the wet season across the PRB (Supplementary Fig. 3), which suggest that the good relationship between DON and \({{\rm{NO}}}_{3}^{-}\) in the wet season is not due to the identical origin (the runoff). Solar radiation affects DON distribution by controlling photosynthesis, a major pathway for N assimilatory uptake in river networks. However, the correlation between DON and \({{\rm{NO}}}_{3}^{-}\) is not observed in the non-carbonate-dominated region. Even though the solar radiation in non-carbonate-dominated regions, such as the DJ and BJ, are similar to some carbonate-dominant regions, such as the Xijiang River Basin (XJ), the DON in these non-carbonate-dominant regions is much lower than in the carbonate-dominated regions (Fig. 3). This corresponds to the comparatively weak transformation from \({{\rm{NO}}}_{3}^{-}\) to DON.

In contrast, phosphate (\({{\rm{PO}}}_{4}^{3-}\), as the most common P species in natural waters34) is significantly higher in the non-carbonate-dominated region than in the carbonate-dominated region (Extended Data Fig. 3), suggesting that P, as the generally considered limiting nutrient35,36, is not the major reason for the observed N uptake zonation. Since C is a fundamental element of organic matter, the abundance of DIC in river water in the carbonate region can support strong autotrophic activities, such as photosynthesis, and boost the N assimilatory uptake, as observed in this study. Even though river water pH is higher in the carbonate-dominated region than the non-carbonate-dominated region (Supplementary Fig. 1), the aqueous carbon dioxide (CO2(aq)) exhibits no significant difference between the two regions (P > 0.05; Extended Data Fig. 4) owing to the greater DIC in the carbonate-dominated region. More importantly, the high bicarbonate (\({{\rm{HCO}}}_{3}^{-}\)) in the carbonate-dominated region can promote the N assimilation process through the direct utilization of \({{\rm{HCO}}}_{3}^{-}\) by both aquatic plants and algae37,38,39. During the dry season, there is no clear contrast of DON zonation owing to the limitation of low temperature and solar radiation on N uptake.

Verified N assimilation enhancement in high-DIC rivers

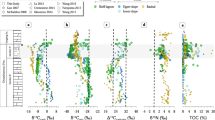

To validate the findings in basin-scale observation, we conducted in situ incubation experiments on two sites in carbonate-dominant and non-carbonate-dominant regions. The environmental characteristics (including solar radiation, water temperature, pH, \({{\rm{NO}}}_{3}^{-}\) and \({{\rm{PO}}}_{4}^{3-}\)) (Fig. 4 and Extended Data Fig. 5) between the two sites were similar within a comparable range, while the major difference was the DIC concentration. The DIC at site 1 (the high-DIC site) was 2,125 μmol l−1, which was about 3.6 times that of site 2 (592 μmol l−1; denoted as low-DIC site). As with the occurrence of N assimilation, the δ15N of particulate organic nitrogen (PON) increases, as observed in incubation results at the high-DIC site. The high-DIC site also shows a strong diurnal pattern and an increase in PON concentration and pH during the daytime (Fig. 4 and Extended Data Fig. 5), indicating strong photosynthesis and \({{\rm{NO}}}_{3}^{-}\) assimilation processes. The N assimilation rate, calculated as the difference in the total organic nitrogen (TON) during the daytime, was 7.4 μmolN l−1 day−1, which is very close to the DIN decrease (8.0 μmolN l−1 day−1). The slight discrepancy may be a result of the potential denitrification or nitrification. The strong photosynthesis and \({{\rm{NO}}}_{3}^{-}\) assimilation processes are also evidenced by the coupled decrease in CO2(aq), DIN and \({{\rm{PO}}}_{4}^{3-}\) (Fig. 4). A net decrease of CO2(aq), DIN and \({{\rm{PO}}}_{4}^{3-}\) with a ∆C:∆N:∆P ratio of 110:16:0.6 was observed in the high-DIC site (Fig. 4), this value is very close to the Redfield ratio (C:N:P of 106:16:1)40, further indicating the occurrence of autotrophic processes.

a–j, The \({{\rm{NO}}}_{3}^{-}\) (a), \({{\rm{NH}}}_{4}^{+}\) (b), \({{\rm{NO}}}_{2}^{-}\) (c), δ15N-PON (d), PON (e), DON (f), CO2(aq) (g), \({{\rm{HCO}}}_{3}^{-}\) (h), \({{\rm{CO}}}_{3}^{2-}\) (i) and \({{\rm{PO}}}_{4}^{3-}\) (j) in the high-DIC (purple) and low-DIC (green) sites. Triplicate incubations were conducted. The scatter plots show the mean (centre) and the s.d. (error bar) of each value. The two-sided Mann–Whitney test is used to evaluate the difference, where P < 0.01 is considered highly significant, P < 0.05 is significant and P values ≥0.05 indicate no statistical significance.

Similar patterns—such as those observed for δ15N-PON—are not observed at the low-DIC site, indicating the weak N assimilation processes. The calculated N assimilation rate was 1 μmolN l−1 day−1, which is less than one-seventh of the rate at the high-DIC site. To confirm that the weak N assimilation in the low-DIC site resulted from the C limitation rather than the P limitation, additional in situ incubations with and without the addition of P were conducted at the low-DIC site. We found that the N assimilation process does not show obvious change after the addition of P (Supplementary Fig. 5), demonstrating that P is not a limiting factor for N assimilation in the low-DIC site. The incubation confirms our basin-scale observations that P is not limited in the non-carbonate-dominated region in the wet season. As expected, during the dry season, the N assimilatory difference between high-DIC and low-DIC rivers is not apparent (Supplementary Text 2).

In summary, the fertilization effects of DIC on N assimilation are evident in the carbonate-dominate region during the wet season, when the temperature and solar radiation are high. In contrast, these effects do not occur in the non-carbonate-dominated region, where the DIC limits the uptake of N. In the dry season, fertilization effects of DIC on N assimilation will not occur in both carbonate-dominate and non-carbonate-dominated regions owing to the limitation of solar radiation and temperature (Fig. 5). On the basis of the results from basin-scale observations and incubation results from both the wet and dry seasons, we modified the temperature, light and nutrient co-controlled phytoplankton growth rate calculations36,41 by adding a DIC-limitation factor, and used it to simulate the phytoplankton growth rate distribution (Fig. 3). The results show that the phytoplankton growth rate is 19% (mean) higher to 31% (median) higher in the carbonate-dominated region than in of the non-carbonate-dominated region of the PRB throughout the year (Extended Data Fig. 6 and Supplementary Fig. 6).

Carbonate weathering controls riverine organic N globally

The observed geological control on riverine organic N formation in river networks is not unique to the PRB, but it is a phenomenon that is overlooked worldwide. Firstly, we find that riverine DIC increases with the watersheds’ carbonate rock proportion globally, which is a result of carbonate weathering (Extended Data Fig. 7). With that, we discovered that TON42 is elevated in rivers (located in Europe and USA) from low to high DIC (Pearson r = 0.53, P < 0.01) (Fig. 6b). Additionally, PON is found to increase with increased basin carbonate proportion based on the observations from 40 rivers across the UK43 (Fig. 6c), with a statistical correlation between carbonate proportion and river median PON after log transformation (Spearman r = 0.50, P < 0.01). PON in the rivers with high carbonate proportions (top half) is significantly higher than those in rivers with low carbonate proportions (P < 0.01) (Fig. 6c). Furthermore, global mean DON generally increased along with the 20-yr average temperature and solar radiation variations from high to low latitude. However, there are exceptions where high DON was found across 45–55° N, attributed to the high anthropogenic N input in Europe44,45. Compared with the solar radiation-controlled and temperature-controlled phytoplankton growth potential (without considering any nutrient limitation), we found that the inclusion of DIC as a limiting factor to phytoplankton growth potential significantly increased the interpretation of the latitudinal distribution of DON in global rivers (uptake rate versus mean DON, Pearson r = 0.57, P < 0.01 excluding 50–55° N) (Fig. 6d).

a, The global distribution of the data in this study. b, The global riverine TON42 varies across low- and high-DIC sites. c, The PON in 40 UK rivers43, and the comparison of PON based on the level of carbonate in the watersheds. The two-sided Mann–Whitney test is applied to evaluate the difference, where P < 0.01 is considered highly significant, P < 0.05 is significant and P values ≥0.05 indicate no statistical significance. d, The global latitudinal variation in DON, simulated growth rate and the distribution of temperature and solar radiation48, the dashed line represents the phytoplankton growth potential (μmax, controlled by temperature and solar radiation) and the solid line represents the DIC-controlled growth potential (μmaxLC, controlled by temperature, solar radiation and DIC). In b, the black dots and the black lines denote to the means and 1.5 IQRs, respectively. In c, the purple and green dots indicate the data points. In c and d, the black dots, the black lines inside the box and the lines outside the boxes represent the mean value, median value and 1.5 IQR, respectively.

To confirm our theory’s universal applicability, we further conducted field sampling in rivers in Malang, Indonesia, with lithological settings similar to the PRB. The results showed that riverine DON is significantly higher (P < 0.05) in the carbonate-dominated rivers than in the non-carbonate-dominated rivers (Extended Data Fig. 8), which is consistent with observations in the PRB, China. Solar radiation46 (non-carbonate of 257.31 W m−2 versus carbonate of 257.44 W m−2) and temperature46 (24.52 °C for non-carbonate versus 25.03 °C for carbonate) are not the causative factors for the difference in DON between the two regions of the Malang site, Indonesia. In addition, the difference in DIN also cannot cause a significant difference in DON (P > 0.05; Supplementary Fig. 7) because the system is P-limited. The slope of \({\rm{DON}}\text{--}{{\rm{PO}}}_{4}^{3-}\) is over two times larger in the carbonate-dominated region than the non-carbonate-dominated region (Extended Data Fig. 8), indicating an amplified response of DON towards P in the carbonate-dominated region owing to the enhancement of high DIC, which confirms our finding in the PRB.

The global TON, PON and DON variations suggest a DIC limitation on riverine N uptake. As silicate covers a larger area of the Earth’s surface, higher DIC induced from chemical weathering in carbonate regions can eliminate the limitation effect and facilitate phytoplankton growth under excess nutrient inputs in rivers. On the basis of the DIC limitation factor that we proposed and the global riverine DIC in high and low carbonate regions (carbonate proportion >50% and <50%, respectively) (Extended Data Fig. 7), we estimate that high carbonate regions can enhance N uptake and phytoplankton growth rate by a mean of 16% up to a median of 31% compared with low carbonate regions under the same temperature and sufficient solar radiation conditions.

Methods

Study area description

The PRB consists of seven sub-basins, respectively, NBP, Yujiang River Basin (YJ), Hongliu River Basin (HL), XJ, BJ, DJ and PRD (Fig. 1). The Geologic composition of the PRB is shown in Fig. 1 (calculated from ref. 47), where the carbonate rocks account for 44% of the total area in the western part (NBP, YJ, HL and XJ), and only represent 8% in the eastern region (BJ, DJ and PRD). In the eastern region of the PRB (BJ, DJ and PRD), the proportion of silicate sedimentary rock (22%) is much higher than that of carbonate rock, especially in the DJ (silicate of 32% and carbonate of 1%) and the PRD (silicate of 16% and carbonate of 1%). On the basis of the bedrock difference, the west four sub-basins are grouped as the carbonate-dominated region and the east three as the non-carbonate-dominated region for analysis.

Field sampling and laboratory analysis

Field samplings were conducted from 10 August to 12 September 2020 (wet season) and 19 December 2022 to 5 March 2023 (dry season). More than 220 river water sites across the entire PRB were sampled, together with 57 groundwater samples (47 in the wet season and 9 in the dry season). We also sampled the discharged water from 25 wastewater treatment plants in the PRD. All water samples were filtered using a membrane with 0.45 μm pore size for dissolved chemical analysis. Environmental variables, such as water temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen, oxidation and reduction potential and so on, were measured in situ using a multiparameter meter (HANNA HI-98194) with accuracy of ±0.15 °C, ±0.02 pH units, ±0.1 mg l−1 and ±1.0 mV. The total alkalinity (TA) was titrated (Hach Digital Titrator, accuracy ±1%) after water collection. Nutrients including \({{\rm{NO}}}_{3}^{-}\), \({{\rm{NH}}}_{4}^{+}\), \({{\rm{NO}}}_{2}^{-}\), \({{\rm{PO}}}_{4}^{3-}\) and dissolved silicon (Si) were analysed with the Seal AA500 AutoAnalyzer (accuracy ±1%), and TDN was measured using the Jena Multi N/C 3100 analyser (accuracy ±3%). DON was calculated as the difference between TDN and DIN. In addition, 15\({\rm{N}}\text{-}{\rm{NO}}_{3}^{-}\) and 18\({\rm{O}}\text{-}{\rm{NO}}_{3}^{-}\) were measured with the Thermo Scientific 253 plus isotope ratio mass spectrometer (accuracy ±0.2%).

We also conducted field sampling at 21 sites in Malang, Indonesia from 6 September to 9 September 2024. The river water samples were collected and filtered using a 0.45 μm membrane filter for dissolved chemical analysis. DIC and TDN were measured using the Jena Multi N/C 3100 analyser (accuracy ±3%), and nutrients including \({{\rm{NO}}}_{3}^{-}\), \({{\rm{NH}}}_{4}^{+}\), \({{\rm{NO}}}_{2}^{-}\) and \({{\rm{PO}}}_{4}^{3-}\) were analysed with the Seal AA500 AutoAnalyzer (accuracy ±1%).

Incubation experiment

The 24-h in situ incubations were conducted to identify the mechanism and validate the basin-level implication. During the wet season, incubation experiments were conducted at the low-DIC site from 21 to 22 September 2023, and at the high-DIC site from 24 to 25 September 2023. During the dry season, experiments were conducted at the low-DIC site from 12 to 13 January 2024, and at the high-DIC site from 15 to 16 January 2024. The experiment started at 6:30 am and ended at 6:30 am the following day. In the field, the original river water was transferred into 625 ml transparent glass bottles. Then, 0.25 ml of 1.207 g l−1 K15NO3 was added to the bottle, serving as the tracers. The total amended 15\({{\rm{N}}{\rm{O}}}_{3}^{-}\) was less than 10% of the ambient \({{\rm{NO}}}_{3}^{-}\) pool to alleviate its impact on the natural N cycle11. Triplicate incubation samples were then placed back on the surface of the river and submerged in the water to main the incubation bottles at the in situ temperature and surface solar radiation. Measurements were taken every 3 h (a total of 27 bottles). Environmental variables were measured using a multiparameter meter (HANNA HI-98194) and TA was titrated with the Hach Digital Titrator. Incubated water samples were sequentially filtered using the 0.7-μm Waterman GF/F membrane and the membrane with 0.45 μm pore size. The Waterman GF/F membrane was carefully folded and the filtrate was analysed for nutrients. For 15N analysis, PON was analysed with the Thermo Scientific 253 plus isotope ratio mass spectrometer (accuracy ±0.2%).

We also conducted the in situ incubation experiment with and without adding \({{\rm{PO}}}_{4}^{3-}\) on 9 August 2024 at the low-DIC site, to determine whether the DON zonation is led by the P limitation. Two incubation groups (blank and experiment) were set up and 0.25 ml of 1.207 g l−1 K15NO3 was added to the 625-ml bottle serving as the tracer. Then, 1 ml of 6.25 mmol l−1 NaH2PO4 was added to the experiment group with an additional 10 μmol l−1 of \({{\rm{PO}}}_{4}^{3-}\). After the addition, the ratio of DIN and dissolved inorganic phosphorus (DIP) in the experiment group reached around 11:1, far lower than the Redfield ratio (N:P of 16:1)40, resulting in an environment enriched in P and eliminating any potential P limiting factors. Triplicate incubation samples for both groups were then placed on the surface of the river and submerged in the water to maintain the incubation bottles at the in situ temperature and surface solar radiation. The ancillary water chemistry, such as pH and dissolved oxygen, were measured every 3 h (a total of 27 bottles). The remaining procedures were the same as those described previously.

Data acquisition and analysis

The DIC is calculated using the CO2SYS programme49 based on field-measured TA, pH, temperature and other relevant parameters. The monthly solar radiation dataset for the PRB analysis is acquired from ref. 48, and the hourly solar radiation for incubation sites is acquired from ref. 50. Furthermore, PON concentrations and carbonate proportion datasets from 40 rivers (1 river from the original dataset is excluded owing to lack of carbonate rocks information) across the UK from the LOCATE project43 were collected, and more than 150,000 rows of metadata for global river DON concentration are collected from previous studies51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69. The TON (located in Europe and the USA) and corresponding DIC data are collected from the GLORICH Project42. In addition, more than 360,000 rows of the global DIC dataset70,71 are collected for analysis. The 20-yr mean global solar radiation and temperature48 were calculated to determine the latitudinal variation. In this study, the organic forms of N, DON, PON and TON were analysed in parallel to multi-explore and verify the impact of lithologic formation on organic N distributions. On the basis of the proportion of carbonate, the top half of rivers (n = 20) are grouped as higher-carbonate regions in the UK, while the lower half are grouped as low carbonate regions. For all the statistical analyses, P < 0.05 is regarded as statistically significant and P < 0.01 is regarded as highly significant.

Growth rate calculation

In biogeochemistry models, the phytoplankton uptake rate of nutrients, or phytoplankton growth rate, is calculated as a function of temperature, solar radiation and nutrient limitation (including N and P)36,41. We further incorporate the DIC as a limitation factor for the terrestrial river ecosystems on the basis of the Michaelis–Menten kinetic as

where μ is the phytoplankton growth rate in d−1, μmax is the light and temperature dependent maximum growth rate (d−1), LN, LP and LC are the limitation factor of DIN, DIP and DIC, respectively.

where μ0 represents the phytoplankton growth rate at 0 °C (d−1), T is water temperature in ref. 41, while air temperature (°C) is used here for estimation due to data scarcity, α is the initial slope of the photosynthesis-irradiance curve (m2 W−1 d−1), I is the solar radiation that is available for photosynthesis in W m−2 and is calculated as the downward short wave solar radiation × 0.43 (ref. 41). For the limitation factors

where \({L}_{{\mathrm{NO}}_{3}^{-}}\) and \({L}_{{\mathrm{NH}}_{4}^{+}}\) represent the \({{\rm{NO}}}_{3}^{-}\) and \({{\rm{NH}}}_{4}^{+}\) limitation factors, and the inhibition effect of the presence of \({{\rm{NH}}}_{4}^{+}\) is considered in \({L}_{{\mathrm{NO}}_{3}^{-}}\) (ref. 41). \({\mathrm{NO}}_{3}^{-}\), \({\mathrm{NH}}_{4}^{+}\), DIP and DIC are the concentrations of \({{\rm{NO}}}_{3}^{-}\), \({{\rm{NH}}}_{4}^{+}\), DIP and DIC in rivers (μmol l−1), respectively. \({k}_{{\mathrm{NO}}_{3}^{-}}\), \({k}_{{\mathrm{NH}}_{4}^{+}}\), \({k}_{\mathrm{DIP}}\) and kDIC are half-saturation concentrations for phytoplankton uptake of \({{\rm{NO}}}_{3}^{-}\), \({{\rm{NH}}}_{4}^{+}\), DIP and DIC (μmol l−1), respectively. μmax is used to represent the global latitudinal phytoplankton growth rate potential line, and μmaxLC is calculated as the DIC-controlled growth rate potential. The median DIC for each 5° latitude bin is used for the estimation.

Data availability

All data displayed in the figures are available at figshare via https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.25395358 (ref. 72).

References

Gruber, N. & Galloway, J. N. An Earth-system perspective of the global nitrogen cycle. Nature 451, 293–296 (2008).

Lu, C. et al. Increased extreme precipitation challenges nitrogen load management to the Gulf of Mexico. Commun. Earth Environ. 1, 21 (2020).

Mulholland, P. J. et al. Stream denitrification across biomes and its response to anthropogenic nitrate loading. Nature 452, 202–205 (2008).

Mulholland, P. J. et al. Stream denitrification and total nitrate uptake rates measured using a field 15N tracer addition approach. Limnol. Oceanogr. 49, 809–820 (2004).

Arango, C. P., Tank, J. L., Johnson, L. T. & Hamilton, S. K. Assimilatory uptake rather than nitrification and denitrification determines nitrogen removal patterns in streams of varying land use. Limnol. Oceanogr. 53, 2558–2572 (2008).

Le, C. et al. Eutrophication of lake waters in China: cost, causes, and control. Environ. Manag. 45, 662–668 (2010).

Seitzinger, S. P. & Sanders, R. W. Contribution of dissolved organic nitrogen from rivers to estuarine eutrophication. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 159, 1–12 (1997).

Hornung, M. in Managing Risks of Nitrates to Humans and the Environment 155–174 (Elsevier, 1999).

Rode, M., Halbedel née Angelstein, S., Anis, M. R., Borchardt, D. & Weitere, M. Continuous in-stream assimilatory nitrate uptake from high-frequency sensor measurements. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 5685–5694 (2016).

de Aguiar do Couto, E., Calijuri, M. L., Assemany, P. P., Tango, M. D. & da Fonseca Santiago, A. Influence of solar radiation on nitrogen recovery by the biomass grown in high rate ponds. Ecol. Eng. 81, 140–145 (2015).

Wang, W. et al. Rates of nitrification and nitrate assimilation in the Changjiang River estuary and adjacent waters based on the nitrogen isotope dilution method. Cont. Shelf Res. 163, 35–43 (2018).

Reay, D. S., Nedwell, D. B., Priddle, J. & Ellis-Evans, J. C. Temperature dependence of inorganic nitrogen uptake: reduced affinity for nitrate at suboptimal temperatures in both algae and bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65, 2577–2584 (1999).

Schmidt, T. S. et al. Geologic processes influence the effects of mining on aquatic ecosystems. Ecol. Appl. 22, 870–879 (2012).

Xiong, L. et al. High-resolution data sets for global carbonate and silicate rock weathering carbon sinks and their change trends. Earth’s Future 10, e2022EF002746 (2022).

Liu, Z., Dreybrodt, W. & Wang, H. A new direction in effective accounting for the atmospheric CO2 budget: considering the combined action of carbonate dissolution, the global water cycle and photosynthetic uptake of DIC by aquatic organisms. Earth-Sci. Rev. 99, 162–172 (2010).

Yang, M., Liu, Z., Sun, H., Yang, R. & Chen, B. Organic carbon source tracing and DIC fertilization effect in the Pearl River: insights from lipid biomarker and geochemical analysis. Appl. Geochem. 73, 132–141 (2016).

Sun, P. A. et al. Dynamics in riverine inorganic and organic carbon based on carbonate weathering coupled with aquatic photosynthesis in a karst catchment, Southwest China. Water Res. 189, 116658 (2021).

Zhao, H., Jiang, Y., Xiao, Q., Zhang, C. & Behzad, H. M. Coupled carbon-nitrogen cycling controls the transformation of dissolved inorganic carbon into dissolved organic carbon in karst aquatic systems. J. Hydrol. 592, 125764 (2021).

Bufe, A. et al. Co-variation of silicate, carbonate and sulfide weathering drives CO2 release with erosion. Nat. Geosci. 14, 211–216 (2021).

Xia, X. et al. The cycle of nitrogen in river systems: sources, transformation, and flux. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2, 863–891 (2018).

Gu, C., Liu, Y., Qi, H. & Lu, M. Influences of carbonate weathering and hyporheic exchange on carbon fluxes in Pearl River Basin, China. Water Res. 261, 122014 (2024).

Xu, M. N. et al. Diel change in inorganic nitrogenous nutrient dynamics and associated oxygen stoichiometry along the Pearl River Estuary. Water Res. 222, 118954 (2022).

Lassaletta, L., García-Gómez, H., Gimeno, B. S. & Rovira, J. V. Agriculture-induced increase in nitrate concentrations in stream waters of a large Mediterranean catchment over 25 years (1981–2005). Sci. Total Environ. 407, 6034–6043 (2009).

Zweimüller, I., Zessner, M. & Hein, T. Effects of climate change on nitrate loads in a large river: the Austrian Danube as example. Hydrol. Process. 22, 1022–1036 (2008).

Lee, T. Y., Huang, J. C., Kao, S. J. & Tung, C. P. Temporal variation of nitrate and phosphate transport in headwater catchments: the hydrological controls and land use alteration. Biogeosciences 10, 2617–2632 (2013).

Zhang, Q. et al. Comprehensive assessment of the utilization of manure in China’s croplands based on national farmer survey data. Sci. Data 10, 223 (2023).

Chen, M. et al. Mixed nitrifying bacteria culture under different temperature dropping strategies: nitrification performance, activity, and community. Chemosphere 195, 800–809 (2018).

Kendall, C., Elliott, E. M. & Wankel, S. D. in Stable Isotopes in Ecology and Environmental Science 375–449 (Wiley, 2007).

Ho, A. Y. T. et al. Phytoplankton biomass and production in subtropical Hong Kong Waters: influence of the Pearl River outflow. Estuaries Coasts 33, 170–181 (2010).

Ehalt Macedo, H. et al. Distribution and characteristics of wastewater treatment plants within the global river network. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 14, 559–577 (2022).

Cui, X., Huang, C., Wu, J., Liu, X. & Hong, Y. Temporal and spatial variations of net anthropogenic nitrogen inputs (NANI) in the Pearl River Basin of China from 1986 to 2015. PLoS ONE https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0228683 (2020).

Bartlett, M. S., Parolari, A. J., McDonnell, J. J. & Porporato, A. Beyond the SCS-CN method: a theoretical framework for spatially lumped rainfall-runoff response. Water Resour. Res. 52, 4608–4627 (2016).

Jaafar, H. H., Ahmad, F. A. & El Beyrouthy, N. GCN250, new global gridded curve numbers for hydrologic modeling and design. Sci. Data 6, 145 (2019).

Packa, V., Bostan, V. & Furdui, V. I. Encyclopedia of Water: Science, Technology, and Society (Elsevier, 2019).

Lan, F., Liu, Q., Ye, W., Wang, X. & Yin, K. Riverine fluxes of different species of phosphorus in the Pearl River estuary. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 200, 116079 (2024).

Yu, L. & Gan, J. Reversing impact of phytoplankton phosphorus limitation on coastal hypoxia due to interacting changes in surface production and shoreward bottom oxygen influx. Water Res. 212, 118094 (2022).

Iversen, L. L. et al. Catchment properties and the photosynthetic trait composition of freshwater plant communities. Science 366, 878–881 (2019).

Nimer, N. A., Iglesias-Rodriguez, M. D. & Merrett, M. J. Bicarbonate utilization by marine phytoplankton species. J. Phycol. 33, 625–631 (1997).

Nayaka, S., Toppo, K. & Verma, S. in Plant Adaptation Strategies in Changing Environment (eds Shukla, V. et al.) 103–115 (Springer, 2017).

Redfield, A. C. On the Proportions of Organic Derivatives in Sea Water and Their Relation to the Composition of Plankton Vol. 1 (Liverpool Univ. Press, 1934).

Fennel, K. et al. Nitrogen cycling in the Middle Atlantic Bight: results from a three-dimensional model and implications for the North Atlantic nitrogen budget. Global Biogeochem. Cycles https://doi.org/10.1029/2005GB002456 (2006).

Hartmann, J., Lauerwald, R. & Moosdorf, N. A brief overview of the Global River Chemistry Database, GLORICH. Procedia Earth Planet. Sci. 10, 23–27 (2014).

Tye, A. et al. Monthly sampling of riverine chemistry and organic matter for 41 rivers in Great Britain in 2017 as part of the LOCATE project. NERC Environmental Information Data Centre https://doi.org/10.5285/08223cdd-5e01-43ad-840d-15ff81e58acf (2020).

Han, Y. et al. Global and regional estimation of net anthropogenic nitrogen inputs (NANI). Geoderma 361, 114066 (2020).

Tysmans, D. J. J., Löhr, A. J., Kroeze, C., Ivens, W. P. M. F. & van Wijnen, J. Spatial and temporal variability of nutrient retention in river basins: a global inventory. Ecol. Indic. 34, 607–615 (2013).

Hersbach, H. et al. ERA5 monthly averaged data on single levels from 1940 to present. Copernic. Clim. Change Data Store 10, 252–266 (2019).

Hartmann, J. & Moosdorf, N. The new global lithological map database GLiM: a representation of rock properties at the Earth surface. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. https://doi.org/10.1029/2012GC004370 (2012).

Muñoz Sabater, J. ERA5-land monthly averaged data from 1950 to present. Copernic. Clim. Change Data Store https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.68d2bb30 (2023).

Lewis, E. & Wallace, D. CO2SYS-Program Developed for the CO2 System Calculations (NOAA, 1998).

Muñoz Sabater, J. ERA5—land hourly data from 1950 to present. Copernicus Climate Change Service Climate Data Store https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.e2161bac (2019).

Badr, E.-S. A. Spatio-temporal variability of dissolved organic nitrogen (DON), carbon (DOC), and nutrients in the Nile River, Egypt. Environ. Monit. Assess. 188, 580 (2016).

Georgia Coastal Ecosystems LTER Project & Hollibaugh, J. T. Water quality monitoring on the Altamaha River and major tributaries from September 2000 through November 2001 ver 21. Environmental Data Initiative https://doi.org/10.6073/pasta/6c342b699a5a524d515f66e1a497c78c (2015).

Hopkinson, C., N. Weston, Plum Island Ecosystems LTER. PIE LTER water-column nutrient and particulate transects along the Parker River Estuary, Massachusetts, 1994–2019. ver 11. Environmental Data Initiative https://doi.org/10.6073/pasta/97a816c48ce6edefc78ad9c731a7817a (2022).

Krishna, M. S. et al. Fluxes of dissolved organic carbon and nitrogen to the northern Indian Ocean from the Indian monsoonal rivers. J. Geophys. Reas. Biogeosci. 120, 2067–2080 (2015).

Lara, R. J. et al. Dissolved organic matter and nutrients in the Lena River, Siberian Arctic: characteristics and distribution. Mar. Chem. 59, 301–309 (1998).

Lorite-Herrera, M., Hiscock, K. & Jiménez-Espinosa, R. Distribution of dissolved inorganic and organic nitrogen in River Water and groundwater in an agriculturally-dominated catchment, South-East Spain. Water Air Soil Pollut. 198, 335–346 (2009).

Mackay, E. B. et al. Dissolved organic nutrient uptake by riverine phytoplankton varies along a gradient of nutrient enrichment. Sci. Total Environ. 722, 137837 (2020).

Mbaye, M. L. et al. Seasonal and spatial variation in suspended matter, organic carbon, nitrogen, and nutrient concentrations of the Senegal River in West Africa. Limnologica 57, 1–13 (2016).

The Arctic Great Rivers Observatory. Water quality dataset, version 20250310. ARTICGRO https://www.arcticgreatrivers.org/data (2024).

Meybeck, M. & Ragu, A. GEMS-GLORI world river discharge database. PANGAEA https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.804574 (2012).

Priestley, S. C. et al. N and C isotope variations along an extreme eutrophication and salinity gradient in the Coorong Lagoon, South Australia. Front. Earth Sci. https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2021.727971 (2022).

Qu, B. et al. Export of dissolved carbonaceous and nitrogenous substances in rivers of the ‘Water Tower of Asia’. J. Environ. Sci. 65, 53–61 (2018).

Stepanauskas, R. et al. Summer inputs of riverine nutrients to the Baltic Sea: bioavailability and eutrophication relevance. Ecol. Monogr. 72, 579–597 (2002).

Takaki, Y., Hattori, K. & Yamashita, Y. Factors controlling the spatial distribution of dissolved organic matter with changes in the C/N ratio from the upper to lower reaches of the Ishikari River, Japan. Front. Earth Sci. https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2022.826907 (2022).

Virro, H., Amatulli, G., Kmoch, A., Shen, L. & Uuemaa, E. GRQA: global river water quality archive. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 13, 5483–5507 (2021).

Wiegner, T. N., Seitzinger, S. P., Glibert, P. M. & Bronk, D. A. J. A. M. E. Bioavailability of dissolved organic nitrogen and carbon from nine rivers in the eastern United States. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 43, 277–287 (2006).

Yan, Z. et al. Active dissolved organic nitrogen cycling hidden in large river and environmental implications. Sci. Total Environ. 795, 148882 (2021).

Zhu, Z. Y. et al. The nonconservative distribution pattern of organic matter in the Rajang, a tropical river with peatland in its estuary. Biogeosciences 17, 2473–2485 (2020).

Holmes, R. M. et al. Climatic Change and Global Warming of Inland Waters (Wiley, 2012); https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118470596.ch1

Raymond, P. A. et al. Global carbon dioxide emissions from inland waters. Nature 503, 355–359 (2013).

Kumar Reddy, S. K., Gupta, H. & Reddy, D. V. Dissolved inorganic carbon export by mountainous tropical rivers of the Western Ghats, India. Chem. Geol. 530, 119316 (2019).

Qi, H. et al. Dataset for carbonate weathering enhances nitrogen assimilatory uptake in rivers globally. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.25395358 (2025).

Acknowledgements

The work described in this paper was substantially supported by a project from Guangdong Province (2023QN10H075) (Y.L.), a project from the Science and Technology Bureau of Guangzhou (2023A03J0640) (Y.L.), a grant from the Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China (project reference no. AoE/P-601/23-N) (Y.L.) and partially supported by funding from CORE (Y.L.). CORE is a joint research centre for ocean research between Laoshan Laboratory and The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (HKUST). This study is also partially supported by the Basic Research Project of Shenzhen Science and Technology Innovation Committee (JCYJ20210324134405014) (J.J.J.) and Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Soil Groundwater Pollution Control (no. 2023B1212060002) (X.K.). We thank X. Luo, C. Gu, H. Wang, Y. Zhang, S. Yu, C. Sheng, J. Zuo, Z. Tan, Y. Huang, C. Xing and S. Zhang for assistance with the fieldwork. We also thank Y. Song and Y. Fan for help with laboratory work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.L. proposed the idea. H.Q. and Y.L. designed the research. H.Q., Y.L., H.W. and A.N.P. performed the fieldwork and experiments. H.Q. performed the analysis and drafted the paper. All authors contributed ideas, interpreted the results, and were involved in editing and writing the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Geoscience thanks Yongjun Jiang, Wilfred Wollheim and Pingheng Yang for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Stefan Lachowycz, in collaboration with the Nature Geoscience team.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 18\({\mathbf{O}}-{\mathbf{NO}}_{\mathbf{3}}^{\mathbf{-}}\) and 15\({\mathbf{N}}-{\mathbf{NO}}_{\mathbf{3}}^{\mathbf{-}}\) isotopic analysis.

Variation of sources are adapted from ref. 28. Linear regression is conducted with groundwater sites. The dashed lines are the linear regression fits, and the shades denote 95% confidence bands.

Extended Data Fig. 2 \({\mathbf{DON}}\!:\!{{\mathbf{NO}}}_{\mathbf{3}}^{\mathbf{-}}\) ratio variation across the PRB.

The two-sided Mann–Whitney test is applied to evaluate the difference between carbonate- and non-carbonate-dominated regions, where p < 0.01 represents highly significant, p < 0.05 represents significant, otherwise there is no statistical significance.

Extended Data Fig. 3 \({{\mathbf{PO}}}_{\mathbf{4}}^{{\mathbf{3}}{\mathbf{-}}}\) distribution across carbonate-dominated and non-carbonate-dominated regions of the PRB.

\({{\rm{PO}}}_{4}^{3-}\) distribution across carbonate-dominated and non-carbonate-dominated regions of the PRB. The two-sided Mann–Whitney test is applied to evaluate the difference between carbonate- and non-carbonate-dominated regions, where p < 0.01 represents highly significant, p < 0.05 represents significant, otherwise there is no statistical significance.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Comparison of CO2(aq), \({{\mathbf{HCO}}}_{\mathbf{3}}^{\mathbf{-}}\), and \({{\mathbf{CO}}}_{\mathbf{3}}^{{\mathbf{2}}{\mathbf{-}}}\) in rivers across the sub-basins during wet and dry seasons.

The distribution of carbonate species CO2(aq) (a), HCO3− (b), and CO32− (c) in sub-basins in wet and dry seasons. The two-sided Mann–Whitney test is applied to evaluate the difference between carbonate- and non-carbonate-dominated regions, where p < 0.01 represents highly significant, p < 0.05 represents significant, otherwise there is no statistical significance.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Environmental variables for incubation experiments in the wet and dry seasons.

(a) temperature, (b) solar radiation, (c) pH for the wet season respectively; (d) temperature, (e) solar radiation, and (f) pH for the dry season respectively. Triplicated incubations were conducted, and the scatter plot shows the mean (centre) and the standard deviation (error bar).

Extended Data Fig. 6 Comparison of calculated phytoplankton growth rates across the PRB in carbonate and non-carbonate-dominated regions.

a,b, The growth rate in wet season (a) and dry season (b), respectively. Zero values are excluded in this figure. The diamond scatter, the line inside the box, lines outside the boxes, and the purple and green dots represent the mean value, median value, 1.5 IQR, and the data, respectively. The two-sided Mann–Whitney test is applied to evaluate the difference between carbonate- and non-carbonate-dominated regions, where p < 0.01 represents highly significant, p < 0.05 represents significant, otherwise there is no statistical significance.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Global DIC in rivers and relationship with watershed carbonate proportion.

(a) global distribution of the DIC dataset70,71; (b) increasing trend of global riverine DIC with watershed carbonate proportion; (c) comparison of riverine DIC in low carbonate (lower 50%) and high carbonate (upper 50%) regions. The boxes represent the 25 to 75% of overall data. The black points, the black line inside the box, the lines outside the boxes, and the purple and green dots represent the mean value, median value, 1.5 IQR, and the data, respectively.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Field sampling sites, lithology, DON, DIC, and \({\mathbf{DON}}-{{\mathbf{PO}}}_{\mathbf{4}}^{{\mathbf{3}}{\mathbf{-}}}\) relationship in Malang, Indonesia in carbonate- and non-carbonate-dominated rivers.

(a) DON distribution and DIC zonation; (b) \({\rm{DON}}-{{\rm{PO}}}_{4}^{3-}\) relationship in carbonate- and non-carbonate-dominated regions. The boxes include 25–75% of overall data. The black points, the black line inside the box, and the lines outside the boxes represent the mean value, median value, and 1.5 IQR, respectively. (c) the \({{\rm{PO}}}_{4}^{3-}\) comparison (d) the DON comparison between carbonate- and non-carbonate-dominated rivers. The two-sided Mann–Whitney test is applied to evaluate the difference between carbonate and non-carbonate regions, where p < 0.01 represents highly significant, p < 0.05 represents significant, otherwise there is no statistical significance. The solid lines in (b) are the linear regression fits, and the shades denote 95% confidence bands.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Texts 1 and 2 and Figs. 1–7.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Qi, H., Liu, Y., Wang, H. et al. Carbonate weathering enhances nitrogen assimilatory uptake in rivers globally. Nat. Geosci. 18, 402–409 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-025-01680-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-025-01680-w

This article is cited by

-

Geological regulation of nitrous oxide emission risks in rivers globally

Communications Earth & Environment (2026)