Abstract

Continued India–Eurasia convergence since the early Palaeogene has led to the formation of the Tibetan Plateau. Yet the primary driving mechanisms of this protracted convergence remain debated, limiting our understanding of continental collision dynamics. Here we provide a holistic quantification of various driving forces to this convergence by integrating high-resolution, plate-boundary-resolving global convection models with observational constraints. Whereas different forces can produce the observed plate motion, we show that the primary driving force can be definitively constrained when Indo-Australian intraplate stress and strain rates are used as constraints in addition to plate motions. Specifically, we identify that the position of the transition in stress orientation within the Indo-Australian plate is highly sensitive to the relative strength of plate-boundary forces. When the plate motion and this stress-orientation transition are fit simultaneously, we find slab pull from Sumatra–Java subduction is the predominant driving force of India–Eurasia convergence with continental collision exerting an overall resisting force and rule out mantle basal drag playing more than a secondary role. We suggest slab pull from adjacent subduction zones has been the primary driver of the uplift of the Tibetan Plateau since its onset and so this may be an exceptional event in Earth’s history.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The World Stress Map data can be accessed at www.world-stress-map.org/. The focal mechanism solution data from International Seismological Centre can be accessed at www.isc.ac.uk. Data generated for this study are available on Dryad at https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.d7wm37qd4 (ref. 62). Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The adaptive nonlinear Stokes solver (Rhea) and scripts related to force calculations are available on Github at https://github.com/johannrudi/rhea. The code and software used to make the figures can be downloaded at www.soest.hawaii.edu/gmt/ and www.paraview.org/. The Matlab script (stress2grid) used to estimate mean SHmax orientations on a regular grid can be downloaded at www.world-stress-map.org/software.

References

Copley, A., Avouac, J.-P. & Royer, J.-Y. India–Asia collision and the Cenozoic slowdown of the Indian plate: implications for the forces driving plate motions. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth https://doi.org/10.1029/2009JB006634 (2010).

Cande, S. C. & Stegman, D. R. Indian and African plate motions driven by the push force of the Réunion plume head. Nature 475, 47–52 (2011).

Zhou, H. et al. India-Eurasia convergence speed-up by passive-margin sediment subduction. Nature 635, 114–120 (2024).

Molnar, P. & Stock, J. M. Slowing of India’s convergence with Eurasia since 20 Ma and its implications for Tibetan mantle dynamics. Tectonics https://doi.org/10.1029/2008TC002271 (2009).

Wu, F., Wan, B., Zhao, L., Xiao, W. & Zhu, R. Tethyan geodynamics. Acta Petrol. Sin. 36, 1627–1674 (2020).

Ghosh, A., Holt, W. E., Flesch, L. M. & Haines, A. J. Gravitational potential energy of the Tibetan Plateau and the forces driving the Indian plate. Geology 34, 321–324 (2006).

Becker, T. W. & Faccenna, C. Mantle conveyor beneath the Tethyan collisional belt. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 310, 453–461 (2011).

Li, Y. et al. Cenozoic India–Asia collision driven by mantle dragging the cratonic root. Nat. Commun. 15, 6674 (2024).

Capitanio, F. A., Morra, G., Goes, S., Weinberg, R. F. & Moresi, L. India–Asia convergence driven by the subduction of the greater Indian continent. Nat. Geosci. 3, 136–139 (2010).

Liang, X. et al. Fragmentation of continental subduction is ending the Himalayan orogeny. Sci. Bull. 68, 3048–3054 (2023).

Bose, S., Schellart, W. P., Strak, V., Duarte, J. C. & Chen, Z. Sunda subduction drives ongoing India–Asia convergence. Tectonophysics 849, 229727 (2023).

Niu, Y. What drives the continued India–Asia convergence since the collision at 55 Ma? Sci. Bull. 65, 169–172 (2020).

Parsons, A. J., Sigloch, K. & Hosseini, K. Australian plate subduction is responsible for northward motion of the India–Asia collision zone and ~1,000 km lateral migration of the Indian slab. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL094904 (2021).

Capitanio, F. A. Current deformation in the Tibetan Plateau: a stress gauge in the India–Asia collision tectonics. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 21, e2019GC008649 (2020).

Capitanio, F. A., Replumaz, A. & Riel, N. Reconciling subduction dynamics during tethys closure with large-scale Asian tectonics: insights from numerical modeling. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 16, 962–982 (2015).

Sternai, P. et al. On the influence of the asthenospheric flow on the tectonics and topography at a collision-subduction transition zones: comparison with the eastern Tibetan margin. J. Geodyn. 100, 184–197 (2016).

Capitanio, F. A. & Replumaz, A. Subduction and slab breakoff controls on Asian indentation tectonics and Himalayan western syntaxis formation. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 14, 3515–3531 (2013).

Bajolet, F., Replumaz, A. & Lainé, R. Orocline and syntaxes formation during subduction and collision. Tectonics 32, 1529–1546 (2013).

Pusok, A. E. & Kaus, B. J. P. Development of topography in 3-D continental-collision models. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 16, 1378–1400 (2015).

Schellart, W. P., Chen, Z., Strak, V., Duarte, J. C. & Rosas, F. M. Pacific subduction control on Asian continental deformation including Tibetan extension and eastward extrusion tectonics. Nat. Commun. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-12337-9 (2019).

Gordon, R. G. & Houseman, G. A. Deformation of Indian Ocean lithosphere: evidence for a highly nonlinear rheological law. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 120, 4434–4449 (2015).

Stadler, G. et al. The dynamics of plate tectonics and mantle flow: from local to global scales. Science 329, 1033–1038 (2010).

Hu, J., Gurnis, M., Rudi, J., Stadler, G. & Müller, R. D. Dynamics of the abrupt change in Pacific Plate motion around 50 million years ago. Nat. Geosci. 15, 74–78 (2022).

Ghosh, A. & Holt, W. E. Plate motions and stresses from global dynamic models. Science 335, 838–843 (2012).

Osei Tutu, A., Sobolev, S. V., Steinberger, B., Popov, A. A. & Rogozhina, I. Evaluating the influence of plate boundary friction and mantle viscosity on plate velocities. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 19, 642–666 (2018).

Mao, W. & Zhong, S. Constraints on mantle viscosity from intermediate-wavelength geoid anomalies in mantle convection models with plate motion history. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 126, e2020JB021561 (2021).

Conrad, C. P. & Lithgow-Bertelloni, C. How mantle slabs drive plate tectonics. Science 298, 207–209 (2002).

Hayes, G. P. et al. Slab2, a comprehensive subduction zone geometry model. Science 362, 58–61 (2018).

Simmons, N. A., Myers, S. C., Johannesson, G. & Matzel, E. LLNL-G3Dv3: global P wave tomography model for improved regional and teleseismic travel time prediction. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth https://doi.org/10.1029/2012JB009525 (2012).

Hu, J., Rudi, J., Gurnis, M. & Stadler, G. Constraining Earth’s nonlinear mantle viscosity using plate-boundary resolving global inversions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2318706121 (2024).

Chen, M. et al. Lithospheric foundering and underthrusting imaged beneath Tibet. Nat. Commun. 8, 15659 (2017).

Wang, Z., Zhao, D., Gao, R. & Hua, Y. Complex subduction beneath the Tibetan Plateau: a slab warping model. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 292, 42–54 (2019).

Li, C. & Van Der Hilst, R. D. Structure of the upper mantle and transition zone beneath Southeast Asia from traveltime tomography. J. Geophys. Res. 115, B07308 (2010).

Steinberger, B. & Calderwood, A. R. Models of large-scale viscous flow in the Earth’s mantle with constraints from mineral physics and surface observations. Geophys. J. Int. 167, 1461–1481 (2006).

Forte, A. M. & Mitrovica, J. X. New inferences of mantle viscosity from joint inversion of long‐wavelength mantle convection and post‐glacial rebound data. Geophys. Res. Lett. 23, 1147–1150 (1996).

Heidbach, O. et al. Plate boundary forces are not enough: second- and third-order stress patterns highlighted in the World Stress Map database. Tectonics https://doi.org/10.1029/2007TC002133 (2007).

Kreemer, C., Blewitt, G. & Klein, E. C. A geodetic plate motion and global strain rate model. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 15, 3849–3889 (2014).

Heidbach, O. et al. The World Stress Map database release 2016: crustal stress pattern across scales. Tectonophysics 744, 484–498 (2018).

Müller, R. D. et al. Ocean basin evolution and global-scale plate reorganization events since Pangea breakup. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 44, 107–138 (2016).

Turcotte, D. L. & Schubert, G. Geodynamics 2nd edn (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2002).

Forsyth, D. & Uyeda, S. On the relative importance of the driving forces of plate motion. Geophys. J. Int. 43, 163–200 (1975).

Molnar, P., England, P. & Martinod, J. Mantle dynamics, uplift of the Tibetan Plateau, and the Indian Monsoon. Rev. Geophys. 31, 357–396 (1993).

Parsons, A. J., Hosseini, K., Palin, R. & Sigloch, K. Geological, geophysical and plate kinematic constraints for models of the India-Asia collision and the post-Triassic central Tethys oceans. Earth Sci. Rev. 208, 103084 (2020).

Warners-Ruckstuhl, K. N., Govers, R. & Wortel, R. Tethyan collision forces and the stress field of the Eurasian Plate. Geophys. J. Int. 195, 1–15 (2013).

Flesch, L. M., Haines, A. J. & Holt, W. E. Dynamics of the India-Eurasia collision zone. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 106, 16435–16460 (2001).

Replumaz, A., Capitanio, F. A., Guillot, S., Negredo, A. M. & Villaseñor, A. The coupling of Indian subduction and Asian continental tectonics. Gondwana Res. 26, 608–626 (2014).

Gibbons, A., Zahirovic, S., Müller, D., Whittaker, J. & Vadakkeyakath, Y. A tectonic model reconciling evidence for the collisions between India, Eurasia and intra-oceanic arcs of the central-eastern Tethys. Gondwana Res. 28, 451–492 (2015).

Bidgood, A. K. et al. The geodynamic significance of continental UHP exhumation: new constraints from the Tso Morari Complex, NW Himalaya. Tectonics 43, e2023TC007976 (2024).

Kapp, P. & Decelles, P. G. Mesozoic–Cenozoic geological evolution of the Himalayan–Tibetan orogen and working tectonic hypotheses. Am. J. Sci. 319, 159–254 (2019).

Ding, L. et al. Timing and mechanisms of Tibetan Plateau uplift. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 3, 652–667 (2022).

Panet, I., Greff-Lefftz, M. & Romanowicz, B. Partial melt in mesoscale upper mantle upwellings beneath ocean basins. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 639, 118763 (2024).

Matsukage, K. N., Jing, Z. & Karato, S.-I. Density of hydrous silicate melt at the conditions of Earth’s deep upper mantle. Nature 438, 488–491 (2005).

Alvarez, W. Protracted continental collisions argue for continental plates driven by basal traction. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 296, 434–442 (2010).

Li, Z.-H., Cui, F., Yang, S. & Zhong, X. Key geodynamic processes and driving forces of Tethyan evolution. Sci. China Earth Sci. 66, 2666–2685 (2023).

Argus, D. F., Gordon, R. G. & DeMets, C. Geologically current motion of 56 plates relative to the no-net-rotation reference frame. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. https://doi.org/10.1029/2011GC003751 (2011).

Hasterok, D. et al. New maps of global geological provinces and tectonic plates. Earth Sci. Rev. 231, 104069 (2022).

Ziegler, M. O. & Heidbach, O. Matlab script Stress2Grid v1.1. GFZ Data Services https://doi.org/10.5880/wsm.2019.002 (2019).

Conrad, C. P. & Lithgow-Bertelloni, C. Influence of continental roots and asthenosphere on plate-mantle coupling. Geophys. Res. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1029/2005GL025621 (2006).

Becker, T. W. On the effect of temperature and strain-rate dependent viscosity on global mantle flow, net rotation, and plate-driving forces. Geophys. J. Int. 167, 943–957 (2006).

Zhang, N., Dang, Z., Huang, C. & Li, Z. X. The dominant driving force for supercontinent breakup: plume push or subduction retreat? Geosci. Front. 9, S167498711830046X (2018).

Huang, C. et al. Modeling the inception of supercontinent breakup: stress state and the importance of orogens. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 20, 4830–4848 (2019).

Zheng, Q. et al. Data from: ongoing India-Eurasia collision predominantly driven by Sumatra-Java slab pull. Dryad https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.d7wm37qd4 (2025).

Bird, P. An updated digital model of plate boundaries. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. https://doi.org/10.1029/2001GC000252 (2003).

Acknowledgements

This study is supported by the National Key R&D Program of China 2023YFF0803200 (J.H.) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) 42174106, 92155307 and 92355302 (J.H.). Q.Z. is supported by the National Key R&D Program of China 2023YFF0803404.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.H. designed the study and constructed the preliminary model. Q.Z. systematically carried out the numerical tests and performed the force calculation. M.G. provided expertise to the geodynamic interpretation. L.C., Y.S., X.B. and Y.Y. contributed to the seismic data analysis and interpretation. All authors participated in result interpretation and paper preparation.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Geoscience thanks Fabio Capitanio, Joao Duarte and Andrew Parsons for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Stefan Lachowycz, in collaboration with the Nature Geoscience team.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

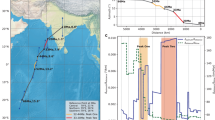

Extended Data Fig. 1 SHmax records and mean orientations for the Indo-Australian plate.

(a) Data records of SHmax. The blue bars indicate SHmax orientations from the World Stress Map 201638, while the brown bars represent focal mechanism solution data from the ISC for the period from January 2016 to October 2023. (b) Mean SHmax orientations on a regular grid of 1.5° computed from the data shown in (a). The inferred position of the SOT is indicated by the magenta dashed line.

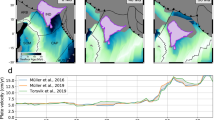

Extended Data Fig. 2 Viscosity fields in geodynamic models.

(a) Details of the Indian subduction beneath the Tibetan Plateau along the profile AA’ in Fig. 1a, inferred from Chen et al.31. (b) Profile with the same location as in (a) but for the structure inferred from Wang et al.32. (c) Details of the Sumatra-Java subduction along the profile BB’ in Fig. 1a. (d) Same profile in (c) but showing the adaptively refined mesh in the region as indicated by the box in (c).

Extended Data Fig. 3 Diagram of the calculation method for plate-boundary forces.

(a) Division of boundaries where plate-boundary forces (B1-B6; red and black lines) are computed. The effective plate-boundary forces and basal drag are calculated at the position marked by the yellow and white stars, respectively. The background color indicates the thickness of the lithosphere, which is defined by an isotherm that is 140 K cooler than the ambient mantle. (b) A sketch showing the calculation of plate-boundary forces. Taking the B1 boundary in (a) as an example, this boundary is hypothetically divided into four great circle arcs A1-A4. Bold arrows n1-n4 denote the normals of each great circle arc. Forces along plate motion are computed, and further used to compute the torque. Dimensions are not to scale.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Effective ridge push for the Central and Southeast Indian Ridge.

(a) ridge push calculated from the analytical formula Eq. (6). Grey lines indicate the depth contours of plate thickness with an interval of 10 km. (b) ridge push calculated from the dynamic pressure of Model 1. The positions of the lines are the same as the depth contours in (a), and the color of the lines represents the line force within the 10 km depth interval.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Predicted plate motion and the second invariant of strain rate tensor from Model 1.

Red arrows show velocities from Model 1; black arrows show velocities from Argus et al.55.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Predicted velocity and viscosity fields at 300 km depth for Model 1 and Model 6.

Results of numerical simulations for Model 1 and Model 6 are shown in (a) and (b), respectively. Black arrows indicate velocities in cm/year.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Predicted plate motions for models.

(a–f) Results of numerical simulations for Model 1 (a), Model 2 (b), Model 3 (c), Model 4 (d), Model 5 (e), and Model 6 (f). In each model, the red arrows represent the velocities predicted by geodynamic models; the black arrows represent the velocities from Argus et al.55. Blue lines show the plate boundaries taken from Bird 200363.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Predicted second invariant of the strain rate tensor.

(a–f) Results of numerical simulations for Model 1 (a), Model 2 (b), Model 3 (c), Model 4 (d), Model 5 (e), and Model 6 (f). Dashed lines indicate the inferred SOT in each model.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Predictions of basal drag beneath the Indian plate and line forces at plate boundaries and inside the plate for Model 1 and Model 5.

Results of numerical simulations for Model 1 and Model 5 are shown in (a) and (b), respectively. Forces are computed from the deviatoric stress. All forces are directed toward the plate motions.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Tables 1–4.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 5

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 6

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 7

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 8

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 9

Statistical source data.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Zheng, Q., Hu, J., Gurnis, M. et al. Ongoing India–Eurasia collision predominantly driven by Sumatra–Java slab pull. Nat. Geosci. 18, 909–915 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-025-01771-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-025-01771-8