Abstract

Ecosystems are not only affected by current climate but are also shaped by antecedent climate through their influences on vegetation growth and environmental conditions. These lagged responses, known as memory effects, can either exacerbate or mitigate the impacts of climate extremes on ecosystem functions. However, the direction, strength and influential duration of memory effects on ecosystem productivity remain poorly understood. Here we implement an interpretable machine-learning framework based on eddy covariance data to model ecosystem gross primary productivity over the period 1995–2020 and further investigate the characteristics of memory effects on positive and negative extremes of ecosystem productivity. Our results show a large contribution from antecedent climate conditions (38.2%) to ecosystem productivity during extremes, with precipitation accounting for 42.2% of the memory effects, followed by temperature (22.1%) and vapour pressure deficit (20.8%). Extreme events conditioned by long-term climatic variations often cause higher productivity losses than short-term extremes, with semi-arid ecosystems exhibiting the largest productivity anomalies and prolonged memory effects. Our results highlight the role of memory effects in regulating carbon flux variations and provide an observation-constrained benchmark for these effects.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All datasets are publicly available. The FLUXNET 2015 dataset is available at http://fluxnet.fluxdata.org/data/fluxnet2015-dataset/; the ERA5-Land dataset is available at https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets/reanalysis-era5-land/; the plant functional type dataset is available at https://lpdaac.usgs.gov/products/mcd12q1v061/; the canopy-height dataset is available at https://langnico.github.io/globalcanopyheight/; the soil properties are available at https://soilgrids.org/ and https://www.futurewater.eu/projects/hihydrosoil/; the nitrogen deposition dataset is available at https://doi.org/10.3334/ORNLDAAC/1220; the topography data are available at https://www.usgs.gov/coastal-changes-and-impacts/gmted2010; the TROPOMI SIF dataset is available at ftp://fluo.gps.caltech.edu/data/tropomi/; the FLUXCOM-X-BASE dataset is available at https://www.icos-cp.eu/data-products/fluxcom-x-global-fluxes-collection; the BESS v2.0 dataset is available at https://www.environment.snu.ac.kr/bessv2; the SMAP L4 carbon product is available at https://nsidc.org/data/spl4cmdl/versions/7 and the Global Forest Change dataset is available at https://glad.earthengine.app/view/global-forest-change. The GPP dataset generated in this study is available via figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29941082.v1 (ref. 76). Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Main codes used for model training and interpretation in this study are available via Github at https://github.com/jhqiu-pku/gpp-interpretive-dl.

References

Reichstein, M. et al. Climate extremes and the carbon cycle. Nature 500, 287–295 (2013).

Dai, A. Increasing drought under global warming in observations and models. Nat. Clim. Change 3, 52–58 (2013).

Yin, J. et al. Large increase in global storm runoff extremes driven by climate and anthropogenic changes. Nat. Commun. 9, 4389 (2018).

Heimann, M. & Reichstein, M. Terrestrial ecosystem carbon dynamics and climate feedbacks. Nature 451, 289–292 (2008).

Keenan, T. F. & Williams, C. A. The terrestrial carbon sink. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 43, 219–243 (2018).

Bousquet, P. et al. Regional changes in carbon dioxide fluxes of land and oceans since 1980. Science 290, 1342–1346 (2000).

Ogle, K. et al. Quantifying ecological memory in plant and ecosystem processes. Ecol. Lett. 18, 221–235 (2015).

Wolf, S. et al. Warm spring reduced carbon cycle impact of the 2012 US summer drought. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 5880–5885 (2016).

Bastos, A. et al. Direct and seasonal legacy effects of the 2018 heat wave and drought on European ecosystem productivity. Sci. Adv. 6, eaba2724 (2020).

Lian, X. et al. Seasonal biological carryover dominates northern vegetation growth. Nat. Commun. 12, 983 (2021).

Lian, X. et al. Diminishing carryover benefits of earlier spring vegetation growth. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 8, 218–228 (2024).

Jump, A. S. et al. Structural overshoot of tree growth with climate variability and the global spectrum of drought-induced forest dieback. Glob. Change Biol. 23, 3742–3757 (2017).

Zhang, Y., Keenan, T. F. & Zhou, S. Exacerbated drought impacts on global ecosystems due to structural overshoot. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 5, 1490–1498 (2021).

Anderegg, W. R. L., Trugman, A. T., Badgley, G., Konings, A. G. & Shaw, J. Divergent forest sensitivity to repeated extreme droughts. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 1091–1095 (2020).

Anderegg, W. R. L. et al. Pervasive drought legacies in forest ecosystems and their implications for carbon cycle models. Science 349, 528–532 (2015).

Buermann, W. et al. Widespread seasonal compensation effects of spring warming on northern plant productivity. Nature 562, 110–114 (2018).

Cranko Page, J. et al. Examining the role of environmental memory in the predictability of carbon and water fluxes across Australian ecosystems. Biogeosciences 19, 1913–1932 (2022).

Wu, D. et al. Time-lag effects of global vegetation responses to climate change. Glob. Change Biol. 21, 3520–3531 (2015).

Liu, Y., Schwalm, C. R., Samuels-Crow, K. E. & Ogle, K. Ecological memory of daily carbon exchange across the globe and its importance in drylands. Ecol. Lett. 22, 1806–1816 (2019).

Huang, M. et al. Air temperature optima of vegetation productivity across global biomes. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 3, 772–779 (2019).

Ponce-Campos, G. E. et al. Ecosystem resilience despite large-scale altered hydroclimatic conditions. Nature 494, 349–352 (2013).

Zaehle, S., Sitch, S., Smith, B. & Hatterman, F. Effects of parameter uncertainties on the modeling of terrestrial biosphere dynamics. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 19, 2004GB002395 (2005).

Morales, P. et al. Comparing and evaluating process-based ecosystem model predictions of carbon and water fluxes in major European forest biomes. Glob. Change Biol. 11, 2211–2233 (2005).

Besnard, S. et al. Memory effects of climate and vegetation affecting net ecosystem CO2 fluxes in global forests. PLoS ONE 14, e0211510 (2019).

Kraft, B. et al. Identifying dynamic memory effects on vegetation state using recurrent neural networks. Front. Big Data 2, 31 (2019).

Liu, W. et al. Importance of the memory effect for assessing interannual variation in net ecosystem exchange. Agric. Meteorol. 341, 109691 (2023).

Liu, G. et al. DeepPhenoMem V1.0: deep learning modelling of canopy greenness dynamics accounting for multi-variate meteorological memory effects on vegetation phenology. Geosci. Model Dev. 17, 6683–6701 (2024).

Kratzert, F. et al. Towards learning universal, regional, and local hydrological behaviors via machine learning applied to large-sample datasets. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 23, 5089–5110 (2019).

Sundararajan, M., Taly, A. & Yan, Q. Axiomatic attribution for deep networks. In Proc. International Conference on Machine Learning (eds Precup, D. & Teh, Y. W.) 3319–3328 (PMLR, 2017).

Tramontana, G. et al. Predicting carbon dioxide and energy fluxes across global FLUXNET sites with regression algorithms. Biogeosciences 13, 4291–4313 (2016).

Frankenberg, C. et al. New global observations of the terrestrial carbon cycle from GOSAT: patterns of plant fluorescence with gross primary productivity. Geophys. Res. Lett. 38, L17706 (2011).

Geirinhas, J. L. et al. Combined large-scale tropical and subtropical forcing on the severe 2019–2022 drought in South America. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 6, 1–13 (2023).

Park, H. et al. Nonlinear response of vegetation green-up to local temperature variations in temperate and boreal forests in the Northern Hemisphere. Remote Sens. Environ. 165, 100–108 (2015).

Fan, L. et al. Negative asymmetric response of pantropical gross primary productivity to precipitation anomalies. Earth’s Future 12, e2024EF004760 (2024).

Medlyn, B. E. et al. Temperature response of parameters of a biochemically based model of photosynthesis. II. a review of experimental data. Plant Cell Environ. 25, 1167–1179 (2002).

Lang, W. et al. Phenological divergence between plants and animals under climate change. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 9, 261–272 (2024).

Huxman, T. E. et al. Convergence across biomes to a common rain-use efficiency. Nature 429, 651–654 (2004).

Dannenberg, M. P., Wise, E. K. & Smith, W. K. Reduced tree growth in the semiarid United States due to asymmetric responses to intensifying precipitation extremes. Sci. Adv. 5, eaaw0667 (2019).

Miguez-Macho, G. & Fan, Y. Spatiotemporal origin of soil water taken up by vegetation. Nature 598, 624–628 (2021).

McDowell, N. G. et al. Mechanisms of plant survival and mortality during drought: why do some plants survive while others succumb to drought?. New Phytol. 178, 719–739 (2008).

McDowell, N. G. et al. Mechanisms of woody-plant mortality under rising drought, CO2 and vapour pressure deficit. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 3, 294–308 (2022).

Gill, S. S. & Tuteja, N. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant machinery in abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 48, 909–930 (2010).

Vicente-Serrano, S. M. et al. Response of vegetation to drought time-scales across global land biomes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 52–57 (2013).

Gao, H. et al. Climate controls how ecosystems size the root zone storage capacity at catchment scale. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 7916–7923 (2014).

Noy-Meir, I. Desert ecosystems: environment and producers. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 4, 25–51 (1973).

Reynolds, J. F., Virginia, R. A., Kemp, P. R., de Soyza, A. G. & Tremmel, D. C. Impact of drought on desert shrubs: effects of seasonality and degree of resource island development. Ecol. Monogr. 69, 69–106 (1999).

Rivero, R. M. et al. Delayed leaf senescence induces extreme drought tolerance in a flowering plant. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 19631–19636 (2007).

Trugman, A. T., Medvigy, D., Mankin, J. S. & Anderegg, W. R. L. Soil moisture stress as a major driver of carbon cycle uncertainty. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 6495–6503 (2018).

Shen, C. et al. Differentiable modelling to unify machine learning and physical models for geosciences. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 4, 552–567 (2023).

Ploton, P. et al. Spatial validation reveals poor predictive performance of large-scale ecological mapping models. Nat. Commun. 11, 4540 (2020).

Kattenborn, T. et al. Spatially autocorrelated training and validation samples inflate performance assessment of convolutional neural networks. ISPRS Open J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 5, 100018 (2022).

Reichstein, M. et al. On the separation of net ecosystem exchange into assimilation and ecosystem respiration: review and improved algorithm. Glob. Change Biol. 11, 1424–1439 (2005).

Lasslop, G. et al. Separation of net ecosystem exchange into assimilation and respiration using a light response curve approach: critical issues and global evaluation. Glob. Change Biol. 16, 187–208 (2010).

Pastorello, G. et al. The FLUXNET2015 dataset and the ONEFlux processing pipeline for eddy covariance data. Sci. Data 7, 225 (2020).

Muñoz-Sabater, J. et al. ERA5-Land: a state-of-the-art global reanalysis dataset for land applications. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 13, 4349–4383 (2021).

Friedl, M. A. et al. Global land cover mapping from MODIS: algorithms and early results. Remote Sens. Environ. 83, 287–302 (2002).

Lang, N., Jetz, W., Schindler, K. & Wegner, J. D. A high-resolution canopy height model of the Earth. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 7, 1778–1789 (2023).

Hengl, T. et al. SoilGrids250m: global gridded soil information based on machine learning. PLoS ONE 12, e0169748 (2017).

Poggio, L. et al. SoilGrids 2.0: producing soil information for the globe with quantified spatial uncertainty. SOIL 7, 217–240 (2021).

Simons, G., Koster, R. & Droogers, P. Hihydrosoil v2.0-high resolution soil maps of global hydraulic properties. FutureWater https://www.futurewater.eu/projects/hihydrosoil/ (2020).

Wei, Y. et al. The North American Carbon Program Multi-scale Synthesis and Terrestrial Model Intercomparison Project–Part 2: environmental driver data. Geosci. Model Dev. 7, 2875–2893 (2014).

Danielson, J. J. & Gesch, D. B. Global Multi-resolution Terrain Elevation Data 2010 (GMTED2010) Open-File Report 2011–1073 (USGS, 2011).

Budyko, M. I. Climate and Life (Academic Press, 1974).

Köhler, P. et al. Global retrievals of solar-Induced chlorophyll fluorescence with TROPOMI: first results and intersensor comparison to OCO-2. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 10,456–10,463 (2018).

Guanter, L. et al. The TROPOSIF global sun-induced fluorescence dataset from the Sentinel-5P TROPOMI mission. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 13, 5423–5440 (2021).

Nelson, J. A. et al. X-BASE: the first terrestrial carbon and water flux products from an extended data-driven scaling framework, FLUXCOM-X. Biogeosciences 21, 5079–5115 (2024).

Li, B. et al. BESSv2.0: a satellite-based and coupled-process model for quantifying long-term global land–atmosphere fluxes. Remote Sens. Environ. 295, 113696 (2023).

Jones, L. A. et al. The SMAP level 4 carbon product for monitoring ecosystem land–atmosphere CO2 exchange. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 55, 6517–6532 (2017).

Hansen, M. C. et al. High-resolution global maps of 21st-century forest cover change. Science 342, 850–853 (2013).

Hochreiter, S. & Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 9, 1735–1780 (1997).

Hochreiter, S., Bengio, Y., Frasconi, P. & Schmidhuber, J. in A Field Guide to Dynamical Recurrent Networks (eds Kolen, J. F. & Kremer, S. C.) 237–243 (Wiley-IEEE, 2001).

He, L. et al. Lagged precipitation effects on plant production across terrestrial biomes. Nat. Ecol. Evol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-025-02806-4 (2025).

Goulden, M. L. & Bales, R. C. California forest die-off linked to multi-year deep soil drying in 2012–2015 drought. Nat. Geosci. 12, 632–637 (2019).

Jung, M. et al. Global patterns of land-atmosphere fluxes of carbon dioxide, latent heat, and sensible heat derived from eddy covariance, satellite, and meteorological observations. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 116, G00J07 (2011).

Lakshminarayanan, B., Pritzel, A. & Blundell, C. Simple and scalable predictive uncertainty estimation using deep ensembles. In 31st Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS 2017) https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper_files/paper/2017/file/9ef2ed4b7fd2c810847ffa5fa85bce38-Paper.pdf (NIPS, 2017).

Qiu, J. et al. Large contribution of antecedent climate to ecosystem productivity anomalies. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29941082.v1 (2025).

Middleton, N. & Thomas, D. S. G. World Atlas of Desertification (UNEP, 1997).

Zomer, R. J., Xu, J. & Trabucco, A. Version 3 of the global aridity index and potential evapotranspiration database. Sci. Data 9, 409 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This study is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42371096, 42141005) and the National Key R & D Program of China (2023YFF0805702). This work is supported by High-performance Computing Platform of Peking University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Z. conceived the idea. Y.Z. and J.Q. designed the study. J.Q. performed the analysis. J.Q. and Y.Z. wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and M.C., T.F.K., H.Z., P.G., L.X., M.C., S.Z. and S.P. commented on the results and contributed to revising the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Geoscience thanks Tyson Terry and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Xujia Jiang, Aliénor Lavergne and Carolina Ortiz Guerrero, in collaboration with the Nature Geoscience team.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Procedure for identifying patterns of memory effects in extreme events.

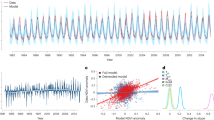

a, Schematic of the data-driven framework. The Entity-Aware Long Short-Term Memory (EA-LSTM) model is trained with meteorological variables over the past 5 years (week t-259 to t) and static variables to predict the GPP of the current week (week t). GPP predictions from multiple trained models are validated against site GPP data and TROPOMI SIF retrievals, and a final model from the model ensemble was selected based on the consistency with SIF. A peak-finding algorithm is applied to the model output to locate global GPP extreme events. The Integrated Gradients (IG) explainer is used to quantify the time-series contributions of meteorological variables during GPP extreme events, thereby identifying distinct patterns of memory effects that indicate divergent vegetation responses to climatic variations during and before these extreme events. b, Illustration of the temporal attribution of extreme events. The y-axis tick labels denote precipitation (Prep), radiation (Rad), temperature (T), vapour pressure deficit (VPD), and wind speed (Ws), respectively, while the x-axis represents the weeks before prediction (Time), covering a five-year range. Each grid represents the contribution of a specific meteorological variable aggregated over a 26-week period during each extreme event. c, Global distribution of the 200 flux tower sites used in this study and their corresponding plant functional types. Basemap data from Natural Earth (https://www.naturalearthdata.com).

Extended Data Fig. 2 Global distribution of GPP extreme events during 1995–2020.

a–b, Global distribution of negative GPP extreme events (a) and positive GPP extreme events (b). Insets show the histograms of the number of the extreme events. c–d, Global distribution of dominant periods of negative GPP extreme events (c) and positive GPP extreme events (d). For each pixel, the dominant period is defined as the time interval with the highest incidence of extreme events per year. Insets show the global temporal development of the number of extreme events per pixel and the corresponding linear trend. Basemap data from Natural Earth (https://www.naturalearthdata.com).

Extended Data Fig. 3 Global patterns of dominant meteorological drivers of GPP anomalies and their memory effects.

a, Annual average spatial distribution of dominant meteorological variables and their corresponding periods of greatest influence. b, Global average of aggregated contributions of meteorological variables over four distinct periods (current month, preceding 2–4 months, 5–12 months, and 13–60 months) across different temporal segments: annual, spring, summer, autumn, and winter. Variable contributions in the Southern Hemisphere undergo a six-month temporal shift to align with the Northern Hemisphere phenology. c–f, Seasonal average spatial distribution of dominant meteorological variables and their corresponding time periods of greatest influence. The seasonal results include four three-month periods: March–May (c), June–August (d), September–November (e), and December–February (f). Insets show the number of pixels dominated by each meteorological variable and their periods of greatest influence. Each variable is represented by colours from dark to light, corresponding to the current month, preceding 2–4 months, 5–12 months, and 13–60 months, respectively. We apply IG on a weekly basis during the period of 2015–2020 to identify the most influential meteorological variables and their time periods of greatest influence for each pixel. Basemap data from Natural Earth (https://www.naturalearthdata.com).

Extended Data Fig. 4 Contributions of dynamic and static variables for the eddy covariance sites.

a, Site-scale average contributions of meteorological variables for all plant functional types except croplands (due to insufficient consideration of human management activities in our model). The bars represent aggregated contributions over four distinct periods (current month, preceding 2–4 months, 5–12 months, and 13–60 months). The bottom x-axis is log-transformed. b, Site-scale average contributions of static variables for all plant functional types except croplands. c, Comparison of the contributions for dynamic and static variables. Shaded areas in a and error bars in a and b indicate the corresponding 95% confidence intervals, averaged over five models (two-sided t-test). Each meteorological variable is represented by colours ranging from dark to light, corresponding to the current month, preceding 2–4 months, 5–12 months, and 13–60 months, respectively.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Spatial patterns of the positive GPP extreme events with different contributions from memory effects.

a–d, Positive GPP anomalies of extreme events dominated by: temperature and current climatic variations (a), temperature and long-term climatic variations (b), water conditions and current climatic variations (c), and water conditions and long-term climatic variations (d). Insets show the average contribution of each meteorological variable aggregated over four distinct periods, with marker size indicating statistical significance. These periods, denoted as P1, P2, P3 and P4, correspond to the current month, the preceding 2–4 months, 5–12 months, and 13–60 months, respectively. Annotations in the lower right corners indicate the percentage of positive extreme events of a specific memory type. e–h, Comparisons between the GPP increases conditioned by current and long-term climatic variations. e and g represent the average GPP increases conditioned by temperature and water conditions, respectively. f and h represent the average GPP increases due to lagged effects in events conditioned by temperature and water conditions, respectively. For e and f, n = 33,870 and 27,203 pixel-events; for g and h, n = 23,418 and 22,492 pixel-events. GPP increases due to lagged effects are computed by aggregating the variable contributions over the periods prior to the current month up to five years. Error bars indicate the ±1 standard deviation of GPP anomalies across events. Asterisks above the bars indicate significant differences between the GPP increases conditioned by current and long-term climatic variations (P < 0.001, one-sided t-test). Basemap data from Natural Earth (https://www.naturalearthdata.com).

Extended Data Fig. 6 Spatial patterns of positive and negative water-dominated GPP extreme events categorized by aridity levels.

a–b, Negative GPP extreme events conditioned by current (a) and long-term (b) climatic variations. c, Average GPP declines during negative GPP extreme events in different aridity levels. d–e, Positive GPP extreme events conditioned by current (d) and long-term (e) climatic variations. f, Average GPP increases during positive GPP extreme events in different aridity levels. Insets show the proportions of different aridity levels. In c and f, dark colours represent GPP anomalies from current effects (aggregated variable contributions over the current month), and light colours represent GPP anomalies due to lagged effects (aggregated variable contributions over periods prior to the current month up to five years). Error bars indicate the ±1 standard deviation of GPP anomalies during extreme events in different climate types. For c, n = 1,133, 5,619, 2,452, and 13,707 pixel-events; for f, n = 17,501, 14,458, 3,030, and 10,921 pixel-events. The climate classification is based on the criteria of the World Atlas of Desertification77 and the aridity index (AI) is sourced from Version 3 of the Global Aridity Index and Potential Evapotranspiration Database78. Here arid, semi-arid, dry subhumid, and humid are defined as AI < 0.2, 0.2 ≤ AI < 0.5, 0.5 ≤ AI < 0.65, and AI ≥ 0.65, respectively. Basemap data from Natural Earth (https://www.naturalearthdata.com).

Extended Data Fig. 7 Impact and attribution of summer drought events preceded by spring GPP surge.

a–e, Spring surge events: occurrence months (a, inset shows the histogram of occurrence months), GPP anomalies (b), temperature contributions aggregated over the current month (c), average variable contributions aggregated over four distinct periods (d), and meteorological anomalies averaged for the same periods (e). f–j, summer drought events: occurrence months (f, inset shows the histogram of occurrence months), GPP anomalies (g), temperature contributions aggregated over the periods prior to the current month up to five years (h), average variable contributions aggregated over four distinct periods (i), and meteorological anomalies averaged for the same periods (j). Marker size indicates statistical significance. P1, P2, P3 and P4 in d, e, i and j denote four distinct time intervals: the current month, the preceding 2–4 months, 5–12 months, and 13–60 months, respectively. Summer drought and spring surge events are identified when a negative GPP extreme event is preceded by a positive event that exceeds a predefined threshold (the mean of the absolute yearly maximum GPP anomalies series) within the past 26 weeks (half a year). Basemap data from Natural Earth (https://www.naturalearthdata.com).

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Text 1–3, Figs. 1–26 and Tables 1–3.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Source data for Fig. 1.

Source Data Fig. 2

Source data for Fig. 2.

Source Data Fig. 3

Source data for Fig. 3.

Source Data Fig. 4

Source data for Fig. 4.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Qiu, J., Zhang, Y., Cai, M. et al. Large contribution of antecedent climate to ecosystem productivity anomalies during extreme events. Nat. Geosci. 19, 25–32 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-025-01856-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-025-01856-4