Abstract

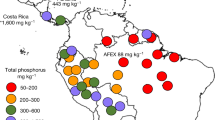

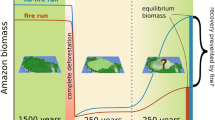

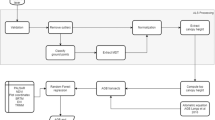

Emissions from deforestation and savannah fires can travel over long distances and contribute to nutrient deposition in intact tropical forests, where phosphorus limits productivity. The magnitude of this deposition and its influence on the carbon sink, however, remain uncertain. Here we used satellite- and model-based geospatial datasets with feature importance analysis to quantify the influence of fire-derived nutrient inputs on Amazon rainforest productivity. Atmospheric transport modelling indicated that plumes originating in the southern arc of deforestation deliver aerosols into the Amazon basin, creating a south-to-northeast gradient in phosphorus deposition across the Amazon rainforest. This gradient in phosphorus deposition aligned with spatial patterns in sun-induced fluorescence, a proxy for gross primary productivity. We show that long-term phosphorus deposition was the strongest predictor of gross primary productivity, accounting for 22.5% of total spatial variability, and was linked to gains of 7.4 gC m−2 yr−1 per 1 mg P m−2 yr−1 deposited. Our results demonstrate that fire-derived deposition can alleviate chronic nutrient limitations in undisturbed tropical forests and influence spatial patterns of productivity. This nutrient fertilization partially offsets carbon losses from deforestation and fires, with important implications for global carbon budgets.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All data related to this Article are available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17516497 (ref. 46). We used the JRC Tropical Moist Forest dataset available at https://forobs.jrc.ec.europa.eu/TMF/data (ref. 35), MERRA-2 black carbon data at https://giovanni.gsfc.nasa.gov/giovanni (ref. 30), P deposition from ORCHIDEE-CNP at https://doi.org/10.17632/f54v9zcgbf.1 (ref. 31), OpenLandMap soil layers at https://openlandmap.org/, ERA5-Land monthly data at https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.68d2bb30 (ref. 41), MOD15A2H leaf area index data at https://doi.org/10.5067/MODIS/MOD15A2H.061 (ref. 29), MOD09GA surface reflectance data at https://doi.org/10.5067/MODIS/MOD09GA.006 (ref. 40), MCD64A1 burned area data at https://doi.org/10.5067/MODIS/MCD64A1.061 (ref. 36), Sentinel-5 carbon monoxide data at https://dataspace.copernicus.eu/, continuous SIF data from OCO-2 at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/8XQY6 (ref. 37), GOSIF data from OCO-2 at https://globalecology.unh.edu/data/GOSIF.html (ref. 37), light-use efficiency SIF PK and JJ data from GOME-2 at https://doi.org/10.2905/21935FFC-B797-4BEE-94DA-8FEC85B3F9E1 (ref. 38), high-resolution global contiguous SIF data from OCO-2 at https://doi.org/10.3334/ORNLDAAC/1863 (ref. 40), AOD data from the AERONET network at https://aeronet.gsfc.nasa.gov, biomass production and soil P uptake data at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2023.110491 (ref. 22) and in situ P deposition measurements at https://doi.org/10.1029/2005GB002541 (ref. 12) and https://doi.org/10.1039/C3EM00641G (ref. 18).

Code availability

The code used to generate the results presented in this study is publicly available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17516497 (ref. 46).

References

Pan, Y. et al. The enduring world forest carbon sink. Nature 631, 563–569 (2024).

Fernández-Martínez, M. et al. Nutrient availability as the key regulator of global forest carbon balance. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 471–476 (2014).

Fleischer, K. et al. Future CO2 fertilization of the Amazon forest hinges on plant phosphorus use and acquisition. Nat. Geosci. 12, 736–741 (2019).

Cunha, H. F. V. et al. Direct evidence for phosphorus limitation on Amazon forest productivity. Nature 608, 558–562 (2022).

Du, E. et al. Global patterns of terrestrial nitrogen and phosphorus limitation. Nat. Geosci. 13, 221–226 (2020).

Chen, Y. et al. Nitrogen deposition in tropical forests from savanna and deforestation fires. Glob. Change Biol. 16, 2024–2038 (2010).

Wang, R. et al. Global forest carbon uptake due to nitrogen and phosphorus deposition from 1850 to 2100. Glob. Change Biol. 23, 4854–4872 (2017).

Bauters, M. et al. High fire-derived nitrogen deposition on central African forests. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 549–554 (2018).

Bauters, M. et al. Fire-derived phosphorus fertilization of African tropical forests. Nat. Commun. 12, 5129 (2021).

Barkley, A. E. et al. African biomass burning is a substantial source of phosphorus deposition to the Amazon, Tropical Atlantic Ocean, and Southern Ocean. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 16216–16221 (2019).

Prospero, J. M. et al. Characterizing and quantifying African dust transport and deposition to South America: implications for the phosphorus budget in the Amazon Basin. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 34, e2020GB006536 (2020).

Mahowald, N. M. et al. Impacts of biomass burning emissions and land use change on Amazonian atmospheric phosphorus cycling and deposition. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 19, 1–15 (2005).

Goll, D. S. et al. Atmospheric phosphorus deposition amplifies carbon sinks in simulations of a tropical forest in Central Africa. New Phytol. 237, 2054–2068 (2023).

Jones, M. W. et al. Global and regional trends and drivers of fire under climate change. Rev. Geophys. 60, e2020RG000726 (2022).

Pöhlker, M. L. et al. Long-term observations of cloud condensation nuclei over the Amazon rain forest—part 2: variability and characteristics of biomass burning, long-range transport, and pristine rain forest aerosols. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 10289–10331 (2018).

Shekhar, A., Buchmann, N. & Gharun, M. How well do recently reconstructed solar-induced fluorescence datasets model gross primary productivity? Remote Sens. Environ. 283, 113282 (2022).

Pickering, M., Cescatti, A. & Duveiller, G. Sun-induced fluorescence as a proxy for primary productivity across vegetation types and climates. Biogeosciences 19, 4833–4864 (2022).

Tipping, E. et al. Atmospheric deposition of phosphorus to land and freshwater. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 16, 1608–1617 (2014).

Andreae, M. O. et al. Transport of biomass burning smoke to the upper troposphere by deep convection in the equatorial region. Geophys. Res. Lett. 28, 951–954 (2001).

Wang, Y. et al. Elucidating climatic drivers of photosynthesis by tropical forests. Glob. Change Biol. 29, 4811–4825 (2023).

Badgley, G., Field, C. B. & Berry, J. A. Canopy near-infrared reflectance and terrestrial photosynthesis. Sci. Adv. 3, e1602244 (2017).

Reichert, T. et al. Modeling the carbon costs of plant phosphorus acquisition in Amazonian forests. Ecol. Model. 485, 110491 (2023).

Darela-Filho, J. P. et al. Reference maps of soil phosphorus for the pan-Amazon region. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 16, 715–729 (2024).

Quesada, C. A. & Lloyd, J. in Interactions Between Biosphere, Atmosphere and Human Land Use in the Amazon Basin 267–299 (Springer, 2016).

Wang, Y. et al. GOLUM-CNP v1. 0: a data-driven modeling of carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus cycles in major terrestrial biomes. Geosci. Model Dev. 11, 3903–3928 (2018).

Dechant, B. et al. Canopy structure explains the relationship between photosynthesis and sun-induced chlorophyll fluorescence in crops. Remote Sens. Environ. 241, 111733 (2020).

Buchhorn, M. et al. Copernicus global land cover layers—collection 2. Remote Sens. 12, 1044 (2020).

Hengl, T. et al. OpenLandMap-soildb: global soil information at 30 m spatial resolution for 2000–2022+ based on spatiotemporal machine learning and harmonized legacy soil samples and observations. Earth Syst. Sci. Data Discuss. 2025, 1–66 (2025).

Myneni, R., Knyazikhin, Y. & Park, T. MODIS/Terra Leaf Area Index/FPAR 8-Day L4 Global 500 m SIN Grid V061 (NASA EOSDIS Land Processes DAAC, 2021).

Gelaro, R. et al. The modern-era retrospective analysis for research and applications, v.2 (MERRA-2). J. Clim. 30, 5419–5454 (2017).

Sun, Y. et al. Global evaluation of nutrient enabled version land surface model ORCHIDEE-CNP v.1.2 (r5986). Geosci. Model Dev. Discuss. 2020, 1987–2010 (2020).

Kanakidou, M., Myriokefalitakis, S. & Tsigaridis, K. Aerosols in atmospheric chemistry and biogeochemical cycles of nutrients. Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 063004 (2018).

Gao, C., He, J., Cong, J., Zhang, S. & Wang, G. Impact of forest fires generated black carbon deposition fluxes in Great Hinggan Mountains (China). Land Degrad. Dev. 29, 2073–2081 (2018).

Vancutsem, C. et al. Long-term (1990–2019) monitoring of forest cover changes in the humid tropics. Sci. Adv. 7, eabe1603 (2021).

Giglio, L., Justice, C., Boschetti, L. & Roy, D. MODIS/Terra+ Aqua Burned Area Monthly L3 Global 500 m SIN Grid V061(NASA EOSDIS Land Processes Distributed Active Archive Center (DAAC), 2021).

Zhang, Y., Joiner, J., Alemohammad, S. H., Zhou, S. & Gentine, P. A global spatially contiguous solar-induced fluorescence (CSIF) dataset using neural networks. Biogeosciences 15, 5779–5800 (2018).

Li, X. & Xiao, J. A global, 0.05-degree product of solar-induced chlorophyll fluorescence derived from OCO-2, MODIS, and reanalysis data. Remote Sens. 11, 517 (2019).

Duveiller, G. et al. A spatially downscaled sun-induced fluorescence global product for enhanced monitoring of vegetation productivity. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 12, 1101–1116 (2020).

Yu, L., Wen, J., Chang, C., Frankenberg, C. & Sun, Y. High-resolution global contiguous SIF of OCO-2. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 1449–1458 (2019).

Vermote, E. MODIS/Aqua Surface Reflectance 8-Day L3 Global 500 m SIN Grid V061(NASA EOSDIS Land Processes DAAC, 2021).

Muñoz-Sabater, J. et al. ERA5-Land: a state-of-the-art global reanalysis dataset for land applications. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 13, 4349–4383 (2021).

Parazoo, N. C. et al. Towards a harmonized long-term spaceborne record of far-red solar-induced fluorescence. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 124, 2518–2539 (2019).

Magalhães, N. de, Evangelista, H., Condom, T., Rabatel, A. & Ginot, P. Amazonian biomass burning enhances tropical Andean glaciers melting. Sci. Rep. 9, 16914 (2019).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32 (2001).

Lundberg, S. M. et al. From local explanations to global understanding with explainable AI for trees. Nat. Mach. Intell. 2, 56–67 (2020).

Descals, A., Peñuelas, J. & Janssens, I. A. Dataset for ‘Distant fires co-determine gross primary productivity in the Amazon rainforest’. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17516497 (2025).

Acknowledgements

A.D. acknowledges funding from 2023 Leonardo Grant for Researchers and Cultural Creators—BBVA Foundation and the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement number 101148378. The BBVA Foundation and the European Union take no responsibility for the opinions, statements and contents of this project, which are entirely the responsibility of its authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.D. designed the research and performed the analysis. A.D., I.A.J. and J.P. contributed ideas to the analysis, methods and results. A.D., I.A.J. and J.P. contributed to the interpretation of the results and to the writing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Geoscience thanks Nicholas Parazoo and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Camilla Brunello, Xujia Jiang and Carolina Ortiz Guerrero in collaboration with the Nature Geoscience team.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Comparison between monthly averaged aerosol optical depth (AOD) and monthly averaged black carbon deposition from MERRA-2.

AOD, at 675 nm, was observed in 16 stations of the AERONET network. The title of the scatterplots shows the mean error (ME), root-mean-squared error (RMSE), coefficient of determination (R2), and number of observations (n). Blue line shows the linear fit.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Coefficient of determination (R2) between monthly averaged aerosol optical depth (AOD) and monthly averaged black carbon deposition from MERRA-2.

AOD, at 675 nm, was observed in 16 stations of the AERONET network. The size of the circles represents the number of observations (n). The coastline was generated from the 100-m resolution CGLS-LC100 land cover dataset.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Spatial patterns of black carbon (BC) deposition, sun-induced fluorescence (SIF), and NIRv across the Amazon rainforest.

Left map shows the Amazon rainforest extent (green) and a transect from point A to point B. Right panels show BC deposition derived from MERRA-2, an ensemble of SIF datasets, and NIRv from MOD09GA along the A–B transect and averaged for 2001-2020. The shaded areas around the lines represent two standard deviations of values within a 100-km buffer along the A–B transect. The land/sea mask was generated from the 100-m resolution CGLS-LC100 land cover dataset.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Frequency and age of atmospheric trajectories originated from fires in South America (upper panels) and Africa (lower panels) between 2001-2020.

The forward trajectories were simulated using the HYSPLIT model. The coastline was generated from the 100-m resolution CGLS-LC100 land cover dataset.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Temporal dynamics of burned area, carbon monoxide (CO) column density, and aerosol optical depth (AOD).

The map (upper left) shows the undisturbed forest from TMF and two regions used to extract daily burned area (black) and CO density (red). The top-right panel shows daily carbon monoxide (CO) from Sentinel-5 (2018–2023) and burned area from MCD64A1 (2001–2023). Middle and bottom panels show daily AOD observations from six AERONET stations. Numbers above boxes indicate sample size. Boxes show the median (red), interquartile range, whiskers for non-outliers, and red ‘+’ for outliers. The land–sea mask is from the 100 m CGLS-LC100 dataset.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Mean absolute SHAP values obtained for long-term climatic variables during the growing season.

The left panel takes gross primary productivity (GPP) as the response variable, while the right panel takes the NIRv from MOD09GA. GPP was estimated from an ensemble of sun-induced fluorescence (SIF) datasets in the Amazon rainforest.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Mean absolute SHAP values obtained for long-term and monthly-scale models.

Right panel shows SHAP values on data that was averaged for the period 2001-2020. Each column represents a model whose response variable is a gross primary production (GPP) estimated from an ensemble of sun-induced fluorescence (SIF) datasets, individual SIF datasets, and NIRv from MOD09GA. Left panel shows the SHAP values on monthly-averaged data; the model was trained with monthly observations for the period 2001-2020.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Sensitivity of new biomass production to soil phosphorus (P) uptake across ten Amazonian forest sites.

Data were extracted from Table 1 and Figure 10 in Reichert et al. (2023). Site TAM-06 was excluded from the regression as it was an outlier with high leverage on the linear regression (bue line; P = 5.8 × 10⁻⁴). The P value was obtained from a two-sided t-test on the regression slope without adjustment for multiple comparisons. Site codes follow Reichert et al. (2023).

Extended Data Fig. 9 Mean absolute SHAP values obtained with long-term variables, including leaf area index.

SHAP values were obtained from a Random Forest model that predicted gross primary production (GPP) and NIRv from MOD09GA in the Amazon rainforest.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Descals, A., Janssens, I.A. & Peñuelas, J. Amazon forest nutrient limitation is mitigated by distant fire emissions. Nat. Geosci. (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-025-01899-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-025-01899-7