Abstract

Theoretical models have been developed to understand how social class influences individual thoughts, feelings and behaviours. However, the validity of these models is threatened by the prevailing use of small, non-diverse samples and flexible measurement practices. We preregistered replications of 35 key hypotheses from 17 correlational and 5 experimental studies, and collected large, quota-based or probability samples from the USA, France, Switzerland and India (Ntotal = 33,536). Our analysis yielded three central findings: (1) ~50% of the effects were successfully replicated; (2) conclusions were consistent across different operationalizations of social class, although objective indicators yielded smaller estimates (for example, income and education); and (3) half of the effects were moderated—mostly strengthened—by social class identification, system-justification beliefs or local income inequality. Overall, hypotheses based on differences between social class contexts in terms of constraints, uncertainty and status were well supported. However, hypotheses based on models positing social class differences in psychological orientations towards ‘the self’ versus ‘others and the environment’ received less support. We conclude that these models need to be reassessed as individuals from higher social classes seem more oriented towards both themselves and others. The Stage 1 protocol for this Registered Report was accepted in principle on 29 October 2021. The protocol, as accepted by the journal, can be found at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/B6Y8R.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

As the topic of socio-economic inequality has gained considerable political momentum in the past decade, psychologists and behavioural scientists have finally turned their attention to the study of social class, developing various theoretical frameworks to account for the role of social class in shaping the way individuals think, feel and behave1,2,3,4,5. These theoretical frameworks describe social class as a relative social position defined by unequal access to economic, cultural, social and/or symbolic resources (for example, income, diplomas and self-perceived rank). Lacking or possessing such resources defines the type of social context to which individuals are exposed: lower social class contexts are often characterized by higher levels of constraints and uncertainty (for example, employment insecurity, scarce resources and social class prejudice), whereas higher social class contexts are characterized by more freedom and volition (for example, employment security, abundant resources and social class privilege). Repeated experiences in these different social contexts shape individuals’ psychological tendencies6,7,8,9. Because individuals from lower social classes live in more unstable and high-constraint contexts, they tend to be more oriented towards others and their environment (manifested in being vigilant to external influences and potential threats, seeing oneself as connected to others, and using community as a resource). By contrast, because individuals from higher social classes live in more stable and low-constraint contexts, they tend to be more oriented towards the self (manifested in being focused on internal states and potential rewards, seeing oneself as unique, and pursuing independence and self-sufficiency).

This central premise has generated a large number of studies documenting the effects of social class10. A literature review led us to identify 35 hypotheses that illustrate the pervasiveness of the psychological impact of social class on (1) the self, (2) relationships, (3) cognition, (4) emotion, (5) social behaviour and (6) decision-making (Table 1). First, regarding the self, the recurring hardships experienced by individuals from lower social classes manifest in a lower sense of control, perceived agency, and self-esteem than those observed in individuals from higher social classes11,12 (see also refs. 13,14,15). Because of the greater constraints and instability of their life contexts, individuals from lower social classes tend to construe their self as interdependent (emphasis on connection to others), whereas individuals from higher social classes construe their self as independent (emphasis on distinctiveness from others)16,17. Second, regarding relationships, individuals from lower social classes tend to develop small, close-knit and homogeneous social networks, which they rely on when facing adversity; by contrast, individuals from higher social classes have more dispersed and diverse networks and prioritize the use of personal economic resources when facing adversity16,18 (for work on social class and intergroup relations, see ref. 19). Third, regarding cognition, differences in terms of other/environment-oriented versus self-oriented psychological tendencies entail different cognitive styles and patterns of sense-making: individuals from lower social classes tend to process information as a global whole, anticipate more change in life trajectories (for example, a higher likelihood of going from being a millionaire to being bankrupt) and produce more contextual explanations of events (for example, failure and success are seen as beyond an individual’s control), whereas individuals from higher social classes process information in parts, anticipate more stability in life trajectories and produce more dispositional explanations of events11,16. Fourth, with respect to emotion, other/environment-oriented versus self-oriented psychological tendencies further suggest that individuals from lower social classes are more prone to other-oriented emotions such as compassion and love, whereas individuals from higher social classes are more prone to self-oriented emotions such as contentment and pride20 (for additional research, see refs. 11,21). Fifth, when it comes to social behaviour, these tendencies ultimately affect unethical and prosocial behaviours. For instance, individuals from lower social classes are more likely to lie when it benefits others (lying for a friend), whereas individuals from higher social classes are more likely to lie when it benefits themselves (lying in one’s own interest)22. Individuals from lower social classes also act more prosocially in private settings, whereas individuals from higher social classes act more prosocially in public settings (when their behaviour could reflect positively on the self)23 (see also ref. 24). Finally, concerning decision-making, owing to cumulative exposure to deprivation (sometimes since childhood), individuals from lower social classes tend to show greater risk aversion, increased preference for immediate rewards (rather than delayed rewards) and higher cognitive load when facing difficult financial decisions than individuals from higher social classes25,26 (for work on social class and moral decision-making, see ref. 27).

Together, the 35 hypotheses derived from the 22 studies referenced in the above paragraph embody a new line of research seeking to understand systematic social class differences that had, until recently, been mostly interpreted as random interindividual differences28. This body of research is highly influential. Although the articles testing these hypotheses have been published over the past decade, they have already garnered large numbers of citations (the median field-weighted citation impact was 3.4, meaning that the articles received 240% more citations than expected on the basis of the average number of citations of similar papers in the discipline over a three-year window)29. Moreover, most of these findings appear in studies published in prestigious, highly visible general or specialized journals such as Science, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences or the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, and some of the findings have been used to inform policymakers (for example, see ref. 30).

However, this body of research is not immune to some of the core challenges faced by the social and behavioural sciences that have led to the “replication crisis”31,32,33: (1) small sample sizes, (2) non-diverse convenience samples and (3) measurement flexibility (either in the choice or in the reporting of the measure). First, the median sample size of the studies is relatively small (215 participants), with a mean statistical power between 0.42 and 0.70 (to detect small (corresponding to r = 0.10) and medium (r = 0.20) psychological effects, respectively34). Second, the vast majority of the studies (86%) use samples that are not distributed similarly to the underlying population in terms of key demographics, one-third use undergraduates and most participants (89%) are from the USA. Third, and finally, the measure of social class varies greatly35 between studies, without—in most cases—any justification provided: the measure is based on participants’ level of education (approximately one-quarter of the studies), income (around one-quarter of the studies) and/or subjective social class (~1/2 of the studies). Each of these three challenges increases the probability of type I errors and threatens generalizability36,37,38. In fact, about half of the critical P values from the 22 studies are above 0.01, when the majority of the P values should be below 0.01 if all effects are true (P values between 0.01 and 0.05 are indicative of lower odds of replication, as the distribution of P values is right-skewed for both adequately and insufficiently powered studies)39,40.

To address these three challenges, we carried out a theoretically comprehensive replication of the 22 studies11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27 described above using (1) samples that yield high power, (2) samples that are either distributed similarly to the national population in terms of key demographics (USA, France and India) or representative of the national population (Switzerland), and (3) a preregistered method and analytical strategy. Specifically, we replicated 17 correlational and 5 experimental studies selected on the basis of criteria related to theoretical relevance, domain coverage and feasibility (for detailed information about the study selection process, see ‘Design’ in Methods). Table 1 lists the hypothesized effects derived from the studies to be replicated, and Supplementary Table 1 lists all the deviations from the original studies (including lab versus online setting, even if—on the basis of the results from Many Labs 2 (ref. 41)—we see no reason to expect this deviation to influence the findings). A detailed description of the preregistered hypotheses, materials and analytical strategies is provided in the Design Table of the Stage 1 protocol and in the preregistration (https://osf.io/3tjzs/).

We recruited a total of N = 33,536 participants from four countries—namely, three samples that are matched to the underlying population in terms of key demographic features (later referred to as quota-based samples) of N = 9,019 US residents, N = 9,160 French residents and N = 9,556 Indian residents and one random representative sample of N = 5,801 Swiss residents. The countries were selected on the basis of both practical and cultural reasons (for detailed information about the selection of countries, see ‘Sampling plan’ in Methods). Importantly, four national samples provided more cultural diversity than is usually found in extant research but are not sufficient to estimate the worldwide generalizability of the findings.

The participants completed a 20-min online questionnaire that included a random subset of 2/3 of the outcome variables used in the original correlational studies and—at most—one experiment. The questionnaire also included nine commonly used measures of social class: education, income, occupation, subjective socio-economic status (SES), childhood subjective SES, childhood SES, social class self-categorization, financial scarcity and sense of power (for detailed information, see ‘Design’ in Methods). Supplementary Tables 4 and 5 present the sample size, reliability and descriptive statistics by country for each social class predictor and each study variable, respectively. For each country, the statistical power to detect a small-sized effect of social class (ηp2 = 0.01) on a given outcome variable was above 0.95 in most cases, although it was lower for the experiments conducted in Switzerland and/or when excluding rushers (for detailed information, see ‘Sampling plan’ in Methods).

The primary purpose of our work was to test the 35 hypotheses derived from the 22 studies using the same analytical strategy used in the original studies (confirmatory preregistered analysis). To ensure the quality and fairness of the replication project, the hypotheses, method and analytical strategy were extracted from the original publications and compiled in a preregistration document; this document was then submitted to the original authors for review and amended according to their feedback. A replication was considered successful if we observed an effect in the same direction as in the original study with an α of 0.05 (for detailed information, see ‘Analysis plan’ in Methods). With samples as large as ours, even practically insignificant effects can be statistically significant42. However, large sample sizes allow one to obtain reliable estimates of effect size, and we used these estimates (along with their confidence intervals) to further describe each replicated effect.

The secondary purpose of our work was to systematically compare the predictive strength of the nine measures of social class when testing the hypotheses (exploratory preregistered analysis). Although social class measures are often used in a flexible way in extant research, theory suggests that these measures should not always be considered interchangeable. Social class contexts involve complex combinations of different types of objective and self-perceived economic, cultural and symbolic resources. These dimensions are related but can be independent (for example, income and education are positively correlated, though one can have a high income level and a low education level). They are associated with different experiences (for example, economic abundance or familiarity with higher social class practices) and could shape different psychological patterns4. Investigating whether and how the different dimensions of social class contexts foster different psychological and behavioural tendencies could facilitate the refinement of theoretical predictions and the development of new insights.

The tertiary purpose of our work was to test three relevant potential moderators of the main effects to be replicated (confirmatory preregistered analysis). First, we tested a moderator located at the intra-individual level: social class identification. Because social class identification is defined as the degree to which an individual assigns subjective value to their social class43, it should logically increase the strength of the effects of social class. Second, we tested a moderator located at the ideological level: system-justification beliefs. However, our prediction was tentative. On the one hand, because believing that society is fair implies that individuals from lower social classes deserve their social status (threatening their ego), system-justification beliefs could increase the strength of most effects of social class (on the self, relationships, emotions and behaviours)15. On the other hand, system-justification beliefs can serve a palliative function for disadvantaged groups (preserving their ego), which could make this prediction inaccurate44,45. Third, we tested a moderator located at the structural level: local income inequality. Because a higher level of income inequality increases the salience of social class stratification46,47, it should increase the strength of the effects of social class. Investigating these moderators should help refine the theoretical framework of the psychology of social class by specifying the boundary conditions of these effects.

Results

Deviations from the preregistered study protocol are reported in detail in the Supplementary Information (‘List of deviations’, pp. 42–44) and summarized in a dedicated section in the Methods.

Primary analysis: replications

In the US sample, where most of the original studies were conducted, the overall replication rate was 56%. In the French, Swiss and Indian samples, the replication rates were 50%, 45% and 41%, respectively. Supplementary Table 6 presents detailed information regarding the calculation of replication rates. These numbers are comparable to those from replication initiatives in psychology, where approximately half of the effects tend to be successfully replicated41,48,49, and they exceed the rate observed in a recent replication initiative focused on the psychology of scarcity (that is, 22%)50. Below, we provide a narrative summary, organized by outcome type, that outlines the conclusions from the tests of the 35 hypotheses in the four samples. Table 2 presents one key statistical result and the overarching conclusion for each country and hypothesis, while Fig. 1 provides a graphical overview of these analyses. The Supplementary Information (‘Detailed report’, pp. 20–32) presents the details of all replication analyses undertaken.

Focal estimates and conclusions for each hypothesis and each country. The central panel shows the β (circles) and 95% CI (error bars) for each hypothesis and country (U, USA; F, France; S, Switzerland; I, India). The upper panel shows the minimum detectable effect size (MDE) with 95% power, vertically aligned with each estimate, with longer arrows indicating greater statistical power (85% of the tests had 95% power detect an effect with ηp2 ≥ 0.01). The right panel shows the ηp2, horizontally aligned with each estimate, with taller shaded areas indicating a greater percentage of variance explained (50% of the effects have ηp2 ≥ 0.01). This figure presents the same focal test per hypothesis as reported in Table 1; the note for Table 1 also applies here. Supplementary Table 9 provides the exact values for ηp2 and MDE used in the upper and right panels. Supplementary Table 5 provides the analytical sample size (N) for each hypothesis and country. The formulas for calculating the MDEs are provided in the Supplementary Information (‘Calculation of the MDE’, p. 33).

The self

The results pertaining to the effects of social class on the self were consistent with seven of the nine original hypotheses in at least two countries. First, in line with the core theoretical tenet that individuals from higher social classes are more inclined to believe that their lives are determined by their own actions, a higher social class was associated with a higher sense of control (H1), increased perceived agency (H2) and more persistent goal striving (H3). The only exception was India, where a higher social class unexpectedly predicted a lower sense of control. Second, illustrating the fact that a higher social class fosters not only a positive self-image but also a self-aggrandizing view of the self, we observed that social class was generally positively associated with self-esteem (H4), narcissism (H5) and entitlement (H6). An exception was Switzerland, where a higher social class unexpectedly predicted a lower level of entitlement. Additionally, outside of the USA, system-justification beliefs did not strengthen the relationship between social class and entitlement (H7). Third, and finally, our data did not support the central idea that individuals from higher social classes endorse and value independence and uniqueness. Specifically, we did not find that individuals from higher social classes hold a more independent self-construal than individuals from lower social classes, except in India (H8). Surprisingly, we found that they reacted more positively, rather than more negatively, when experiencing reduced individuation (H9) in the US, Swiss and Indian samples.

Summary

Consistent with earlier findings, higher social class is generally associated with a greater sense of control, agency, persistence, self-esteem, narcissism and entitlement. Inconsistent with earlier findings, higher social class is generally associated with a more positive (rather than negative) reaction to reduced individuation, while there is little evidence for social class differences in self-construal or for an interaction effect between social class and system-justification beliefs on entitlement.

Relationships

The results pertaining to the effects of social class on relationships were consistent with three of the seven original hypotheses in at least two countries. First, our results provided mixed support for the central premise that individuals from lower social classes enjoy more tight-knit, intimate and supportive relationships than individuals from higher social classes. On the one hand, we did observe that individuals from lower social classes generally included a higher proportion of their network members in their inner circle (H10), although the effect was reversed in India. On the other hand, we did not observe that individuals from lower social classes received more social support from their network (H11); in fact, they reported experiencing more social annoyance in both the USA and India. Second, our results did not support the hypothesis that individuals from lower social classes prioritize relationships to cope with future financial instability (H12) or that those from higher social classes prioritize money (H13). Instead, in France and India, it was individuals from higher social classes who demonstrated a more communal orientation when expecting financial stability. Third, regarding intergroup relations, participants from all four countries consistently showed a bias against lower-educated individuals (H14), particularly when they themselves belonged to a higher social class (H15). However, in the two countries where the comparison was possible, our analysis indicated that the size of the education bias was not equivalent to, but smaller than, that of the ethnicity bias (H16).

Summary

Consistent with earlier findings, higher social class is generally associated with a looser social network and greater bias against individuals with lower education. Inconsistent with earlier findings, higher social class is generally associated with greater (rather than lesser) social support and with a greater reliance on friendship in times of financial stability (rather than on money in times of financial instability). Finally, education bias is weaker, rather than similar to, ethnic bias.

Cognition

The results pertaining to the effects of social class on cognition were consistent with two of the four original hypotheses in at least two countries. First, our findings were mostly congruent with the theoretical claim that individuals from higher social classes exhibit a more analytical cognitive style, while individuals from lower social classes exhibit a more holistic cognitive style. We observed that individuals from higher social classes systematically favoured taxonomic (indicative of analytical thinking) rather than thematic (indicative of holistic thinking) categorization (H17). Additionally, individuals from higher social classes saw life trajectories as more linear and less susceptible to change (also indicative of analytical thinking) (H18), except in the USA. Second, our findings were mostly incongruent with the claim that social class predicts different attributional patterns. Only in Switzerland did we observe that individuals from lower social classes were more likely to explain life events (for example, being laid off) using contextual rather than dispositional causes (H19), a relationship that—as in the original study—was mediated by a lower level of sense of control (H20). In France, we observed no such relationship, while in the USA and India, individuals from lower social classes were in fact more likely to offer dispositional explanations of life events.

Summary

Consistent with earlier findings, higher social class is generally associated with more taxonomic categorization and less anticipation of change in life trajectories. Inconsistent with earlier findings, the association between social class and attribution patterns varies across countries.

Emotions

The results pertaining to the effects of social class on emotions were consistent with two of the six original hypotheses in at least two countries. First, our data offered mixed support for the key proposition that social class differences in terms of self- and other-orientation manifest in different experiences of positive emotions. On the one hand, there was some evidence that individuals from higher social classes experience more self-oriented positive emotions: they reported higher levels of both contentment (H23) and pride (H24). The sole exception was India, where they reported feeling less, not more, contentment. On the other hand, there was very little evidence that individuals from lower social classes experience more other-oriented positive emotions: only in the USA did they report experiencing greater compassion (H21), and generally, they reported experiencing less, not more, love (H22). Second, regarding negative emotions, our data did not substantiate the hypothesis that individuals from lower social classes experience more negative self-conscious emotions when a stranger shares fewer resources with them in a dictator game (H25). Third, contrary to the hypothesis that individuals from lower social classes are more attentive to contextual information (H26), we observed that individuals from higher social classes were more influenced by contextual information when rating emotional facial expressions.

Summary

Consistent with earlier findings, higher social class is generally associated with more contentment and more pride. Inconsistent with earlier findings, higher social class is generally associated with more (rather than less) love and more (rather than less) sensitivity to contextual emotional cues, while there is little evidence for social class differences in compassion or for an interaction effect between social class and negative sharing interactions on self-conscious emotions.

Behaviour

The results pertaining to the effects of social class on behaviour were not consistent with the three original hypotheses. Generally, our data contradicted the idea that individuals from higher social classes are more self-oriented and have fewer concerns for others, and therefore engage in more unethical behaviour. We found no evidence that individuals from higher social classes were more likely to use deception in a hypothetical negotiation task (H29). In most samples, they were in fact less, not more, likely to act unethically in this task. Additionally, our findings indicated that the relationship between social class and unethical behaviour is not moderated by the context of behaviour (that is, cheating for oneself versus for others or being generous in public versus private). We found no evidence that individuals from higher social classes engage in more unethical behaviour when it benefits themselves rather than others (H27). Similarly, we found no evidence that individuals from higher social classes donate fewer tickets in a dictator game in private contexts (where generosity is driven by intrinsic concerns for others) than in public contexts (where generosity is driven by strategic concerns of positive self-image) (H28).

Summary

None of the effects are consistent with earlier findings. Inconsistent with earlier findings, higher social class is generally associated with less (rather than more) unethical behaviours, while there is little evidence for an interaction effect between social class and other- versus self-beneficial behaviour on unethical behaviour, or for an interaction effect between social class and private versus public context on generosity.

Decision-making

The results pertaining to the effects of social class on decision-making were consistent with two of the six original hypotheses in at least two countries. First, our results offered partial support for the theoretical proposition that past experiences of hardship lead individuals from lower social classes to avoid financial risks and prefer smaller immediate gains to larger future gains. On the one hand, consistent with the original hypothesis, individuals from lower social classes were generally more risk-averse than individuals from higher social classes (H30). On the other hand, except in India, individuals from lower social classes did not demonstrate a stronger preference for immediate pay-offs over delayed ones (H31). However, the results of the equivalence tests were inconclusive, preventing us from determining whether there was indeed no interaction effect between social class and the salience of a dangerous world on financial risk aversion (H32) or preference for delayed reward, as hypothesized (H33). Second, only in France did our findings provide support for the idea that asking individuals from lower social classes to think about hard rather than easy financial decisions results in an increase in cognitive load negatively affecting their performance on Raven’s Matrices (H34). Third, and finally, as expected, individuals from higher social classes favoured utilitarian over deontological decisions when faced with the trolley dilemma (H35).

Summary

Consistent with earlier findings, higher social class is generally associated with less risk aversion and more utilitarian moral decisions. Inconsistent with earlier findings, there is little evidence for social class differences in preference for delayed reward or for an interaction effect between social class and exposure to easy versus difficult financial problems on cognitive load.

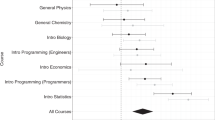

Secondary analysis: comparison of social class measures

Direction of the estimates

We re-examined each hypothesis using the nine social class indicators in the data pooled from the four samples. A comparison of the indicators suggests that the operationalization of social class had minimal influence on the direction and significance of the standardized estimates. Figure 2 illustrates this by showing when the estimate is positive (green), negative (red) or non-significant (grey), along with a tally of these estimates by hypothesis on the right-hand side. For each hypothesis, at least five of the nine social class indicators produced similar results in terms of both the sign of estimates and statistical significance. For 3/4 of the hypotheses, seven or more of the nine indicators yielded similar conclusions. This suggests that researchers studying the influence of social class on the self, relationships, cognition, emotions, decision-making or behaviours are likely to reach similar conclusions, whether they use objective or subjective measures of current or childhood social class. Despite the overall uniformity in the findings, two cases stand out as exceptions: both measures of childhood SES were negatively, rather than positively, associated with sense of control, and both income and education were negatively, rather than positively, associated with utilitarian moral decision-making.

Comparison of the nine social class indicators for each relevant hypothesis in the pooled sample. This figure presents the standardized coefficient estimates from fixed-effects regressions (with country fixed effects) testing the link between each social class indicator and outcome (excluding the original control variables for comparability). The sign of the hypothesized effect of social class is indicated in parentheses after the outcome in the first column. Five hypotheses were excluded from the analysis because social class was not the predictor (H14 and H16), they pertained to an indirect effect (H20) or they predicted a null moderation (H32–H33). Darker green cases indicate more positive estimates, darker red cases indicate more negative estimates and grey cases indicate non-significant estimates (after correction for multiple comparisons). Education is the planned contrast (−0.5, lowest group; 0, middle; 0.5, highest). Income was log-transformed and rescaled within countries to account for differences in monetary units (that is, 1 unit = 1 s.d.(log(income))within). Financial scarcity was reverse-coded, with a higher score indicating higher social class. Objective indicators are education, income, occupation and scarcity. \(\overline{\beta }\) indicates the average standardized coefficient across social class indicators. ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05 (significance levels were adjusted for multiple testing for each hypothesis using a sequential Bonferroni procedure; the exact P values can be found in Supplementary Table 11).

Magnitude of the estimates

However, the operationalization of social class did influence the magnitude of the standardized estimates. Figure 2 illustrates this by assigning different superscript letters to adjacent estimates that were significantly different and by showing the standard deviation of the estimates on the right-hand side. For over 70% of the hypotheses, at least one of the social class indicators yielded a larger estimate than the others. The variation between indicators was especially pronounced for hypotheses concerning the self or self-reported emotions, and less so for those related to relationships or decision-making. For the 21 hypotheses where social class indicators yielded different estimate sizes, childhood SES was most often the strongest or second-strongest indicator (16 times), followed by sense of power (15 times) and subjective SES (10 times). This result is perhaps not surprising given that these indicators capture subjective perceptions and experiences of social class, making them more proximal to psychological tendencies. The last row of Fig. 2 depicts the mean absolute effect size for each indicator. It shows slightly larger estimates (0.07 < β < 0.15) for indicators focused on perceived or experienced social standing than for those focused on objective life circumstances (0.05 < β < 0.06).

Connection with the replications

We generally found that the conclusions from the replication analyses were unaffected by how social class was operationalized. Broadly speaking, hypothesized effects that replicated or failed to replicate in the primary analysis exhibited similar patterns across most indicators in the secondary analysis. However, there were exceptions. First, three hypotheses that were not supported in the primary analysis received support in the pooled sample. Social class did predict a preference for immediate pay-offs over delayed ones for 8 out of 9 of the indicators (H30), system-justification beliefs did strengthen the link between social class and entitlement for all indicators (H7) and thinking about hard (versus easy) problems did cause individuals with lower income and lower childhood SES to perform worse on Raven’s Matrices (H34). Second, three hypothesized effects that were mostly null in the primary analysis turned out to be in the opposite direction in the pooled sample. A higher social class predicted a more interdependent self-construal, rather than a more independent self-construal, for 5 out of 9 of the indicators (H8), as well as higher levels of compassion, rather than lower levels, for 8 out of 9 of the indicators (H21). Moreover, social class interacted with financial stability in predicting communal orientation for 7 out of 9 of the indicators (H12). However, simple slope analyses revealed patterns inconsistent with the hypothesis, as instability did not increase communality among individuals from lower social classes but instead lowered it among those from higher social classes. Third, while the effect of social class, as measured by education, on anticipation of change was mostly negative in the primary analysis, it was positive (that is, reversed) for 5 out of 9 of the indicators (H18).

Summary

While the direction of the estimates and the conclusions of the replication do not depend much on which social class indicator is used (with some exceptions), the magnitude of the estimates is smaller when using objective indicators.

Tertiary analysis: moderation

Our general hypothesis is that the effects of social class are strengthened by social class identification, system-justification beliefs and local inequality. In most cases, we considered the hypothesis supported when the effect of social class as hypothesized in Table 1 was strengthened. In the few cases where the effect in the secondary analyses was mostly in the opposite direction to the prediction, we considered our hypothesis supported when the observed (rather than the hypothesized) effect was strengthened (see the caption for Fig. 3 and ‘Summary of the deviations from preregistration’ in Methods). Generally, estimates highlighted in blue in Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 12 indicate support for the hypothesis.

Interaction between each social class indicator and moderator in the pooled sample. Each panel of this figure displays coefficient estimates from fixed-effects regression models (with country fixed effects) testing interaction effects between a specific social class indicator and social class identification (left), system-justification beliefs (middle) and local income inequality (right) on a given outcome (excluding the original control variables for comparability). Counts of significant strengthening interactions, significant weakening interactions, and non-significant interactions appear on the right of each panel, with the largest count in bold. H12′–H14′, H25′, H16′, H27′–H28′ and H32′–H33′ were not tested because these hypotheses do not involve main effects of social class. Supplementary Table 12 provides the estimates for the 23 (hypotheses) × 9 (indicators) × 3 (moderators) = 621 interactions, along with the simple slopes. For the hypotheses marked with a superscript ‘a’, the statistical effect of social class observed in the secondary analysis was in the opposite direction to the original hypothesis for the majority of indicators; thus, the interactions refer to a strengthening or weakening effect of the observed social class effect in the secondary analysis rather than to the original hypothesized effect.

Social class identification

Our hypothesis was that social class differences are larger among individuals for whom social class is a more important part of their identity. The left panel of Fig. 3 shows whether, supporting our hypotheses, social class differences widen with increasing identification (strengthening interactions in blue) or, on the contrary, narrow (weakening interactions in orange). For this and subsequent analyses, Supplementary Table 12 provides estimates for all interactions, as well as simple slopes. For 35% of the hypotheses, in line with our predictions, social class identification strengthened the statistical effects of most social class indicators. Specifically, identification reinforced the tendency of individuals from higher social classes to see themselves as more agentic (H2′), to adopt a more self-aggrandizing view of the self (H5′–H6′), to perceive life trajectories as more susceptible to change (H18′), to attribute life events to more external causes (H19′), to display more ethical behaviour (H29′), to take more financial risks (H31′) and to engage in more utilitarian decision-making (H35′). For 9% of the hypotheses, contrary to our predictions, social class identification weakened the statistical effects of most social class indicators. Specifically, identification attenuated the tendency of individuals from higher social classes to report a higher sense of control (H1′) and self-esteem (H4′). For 52% of the hypotheses, social class identification did not significantly interact with the majority of indicators. For the remaining hypothesis (H3′), the results were mixed.

System-justification beliefs

Our hypothesis was that social class differences are larger among individuals who believe that society is fair. The middle panel of Fig. 3 shows whether, supporting our hypotheses, social class differences widen with increasing system justification (strengthening interactions in blue) or, on the contrary, narrow (weakening interactions in orange). For 52% of the hypotheses, in line with our predictions, system-justification beliefs strengthened the statistical effects of most social class indicators. Specifically, system justification reinforces the tendency of individuals from higher social classes to see themselves as more agentic (H2′); to adopt a more self-aggrandizing view of the self (H5′–H6′); to hold a more interdependent self-construal (H8′); to receive more social support from their network (H11′); to perceive life trajectories as more susceptible to change (H18′); to attribute life events to more external causes (H19′); to experience more compassion (H21′), love (H22′) and pride (H24′); to display more ethical behaviour (H29′); and to engage in more utilitarian decision-making (H35′). For 17% of the hypotheses, contrary to our predictions, system-justification beliefs weakened the statistical effects of most social class indicators. Specifically, system justification attenuates the tendency of individuals from higher social classes to report higher sense of control (H1′) and self-esteem (H4′), bias against lower-educated people (H15′), and preference for larger future gains over smaller immediate gains (H30′). For 22% of the hypotheses, system-justification beliefs did not significantly interact with the majority of indicators. For the remaining two hypotheses (H3′ and H23′), the results were mixed.

Local income inequality

Our hypothesis was that social class differences are larger among individuals who live in locales with higher income inequality. The right panel of Fig. 3 shows whether, supporting our hypotheses, social class differences widen with increasing inequality (strengthening interactions in blue) or, on the contrary, narrow (weakening interactions in orange). For 22% of the hypotheses, in line with our predictions, local income inequality strengthened the statistical effects of most social class indicators. Specifically, inequality reinforces the tendency of individuals from higher social classes to feel more entitled (H6′), to hold a more interdependent self-construal (H8′), to perceive life trajectories as more susceptible to change (H18′), to attribute life events to more external causes (H19′) and to engage in more utilitarian decision-making (H35′). For one of the hypotheses, local income inequality weakened the statistical effects of social class indicators on outcomes. Specifically, local income inequality attenuates the tendency of individuals from higher social classes to report a higher sense of control (H1′). For the remaining 74% of the hypotheses, local income inequality did not significantly interact with the majority of indicators.

Connection with the replications

We wish to highlight three instances where the original statistical effect of social class was not consistently replicated in either the primary or secondary analysis but was observed at a conditional value of the moderator in the tertiary analysis. First, for most indicators, we found that a higher social class was associated with perceiving life trajectories as less susceptible to change among individuals with low social class identification or weak system-justification beliefs. Second, for some indicators, we found that a higher social class was associated with a less interdependent self-construal among individuals with low social class identification, with weak system-justification beliefs or living in more economically unequal places. Third, and finally, for some indicators, we found that a higher social class was associated with fewer other-oriented emotions (that is, compassion and love) among individuals with weak system-justification beliefs. These results suggest that the replication of social class tendencies might sometimes depend on individual, ideological or structural factors.

Summary

Identification, system-justification and income inequality increased the predictive strength of social class for 1/3, 1/2 and 1/5 of outcomes, respectively. Interestingly, the hypothesized effects of social class on anticipation of change, interdependent self-construal and other-oriented emotions—which were not replicated in the previous parts—were observed at certain values of the moderators.

Discussion

This article had three objectives. The first was to assess the overall replicability of the psychological effects of social class in four countries. We successfully replicated half of the selected hypothesized effects, with higher replication rates in the domain of the self and lower rates in the domain of behaviour. About 50% of the significant effects of social class were of a very small to small size (ηp2 ≤ 0.01). The second objective was to compare the predictive strength of nine commonly used indicators of social class. Since these indicators capture different aspects of social class, we aimed to clarify how they differentially relate to psychological outcomes51. Despite their conceptual differences, our results suggest that these indicators generally lead to similar conclusions in terms of direction and significance. However, there were variations in effect sizes. Specifically, subjective indicators showed stronger associations with psychological outcomes than objective indicators. This may not be surprising, as subjective indicators inherently capture the psychological dimension of social class experience52. Importantly, it should be noted that our conclusions about indicators is contingent on both the outcomes and the specific measures examined. Regarding outcomes, variables beyond those studied here—such as political attitudes—are known to be strongly predicted by education53,54,55. Regarding the indicators, we selected those commonly used in the replicated studies (for example, a subjective SES ladder using the community as a comparison point), but we cannot rule out the possibility that alternative measures might have produced different effects (for example, a subjective SES ladder using society as a comparison point). The third objective was to test whether social class identification, system-justification beliefs and local income inequality strengthened the effect of social class. System justification was the moderator with the most significant interactions, followed by identification and then inequality. Across moderators, when the interactions were significant, social class differences tended to widen (rather than narrow) in the majority of cases (~80%) at high levels of the moderator. While our study focuses on these three specific moderators, our dataset includes numerous other variables that could be used to explore intersectionality between social class and other factors such as gender and ethnicity56,57.

Re-evaluating key claims in the psychology of social class

In light of these findings, we re-evaluate central claims in the psychology of social class to provide an updated overview of the state of the field. We have tried in good faith to give an account of the dominant trends (that is, effects observed in the majority of tests in the first two empirical sections), while recognizing that this account may not fully capture the nuances of the thousands of analyses performed. As seen in Fig. 4, we propose that most of the hypotheses examined can be categorized into two tiers.

The first tier includes hypotheses on how social class contexts differ in terms of constraint, uncertainty and status and how they shape proximal individual outcomes. This idea is not specific to the psychology of social class and can be found in other fields relevant to social stratification (for example, evolutionary-developmental approaches, welfare economics and social epidemiology)25,58,59,60,61. We identified three claims in this tier. Claim 1.1 is that lower social class contexts are high-constraint environments where individuals experience limited volition and freedom. Consistent with this claim, we found that individuals from lower social classes report a lower sense of control, agency and persistence. Claim 1.2 is that lower social class contexts are highly uncertain environments where taking chances carries potential costs. Supporting this claim, we found that individuals from lower social classes demonstrate greater financial risk aversion and a preference for immediate rewards over future benefits. Claim 1.3 is that individuals in lower social class contexts lack status. Consistent with this claim, we observed a pervasive education bias across countries, especially among individuals from higher social classes. Also consistent, we found that individuals from higher social classes benefit from higher self-esteem, which can veer into narcissistic tendencies and feelings of entitlement. Overall, these three claims are well supported by our data.

The second tier includes hypotheses on how the aforementioned differences in social class context (vis-à-vis constraint, uncertainty and status) translate into distinct general psychological orientations (towards the self, others and the environment) and shape more distal individual outcomes. These hypotheses are derived from the models of the psychology of social class2,9,10. We identified five claims in this tier. Claim 2.1 is that individuals from lower social classes have a more interdependent self-construal. Consistent with this claim, we found that individuals from lower social classes maintain tighter social networks; however, this did not translate into receiving more social support. Inconsistent with this claim, we mostly found that individuals from higher, not lower, social classes report a more interdependent self-construal and show more positive reactions to similarity to others. Moreover, a central aspect of this claim is that individuals from lower social classes rely on others to cope with hardship, whereas individuals from higher social classes rely on their financial resources. Contrary to this idea, we found that individuals from higher social classes expecting hardship do not increase their reliance on money but instead display a reduced communal orientation. Claim 2.2 is that individuals from lower social classes adopt a holistic thinking style whereas individuals from higher social classes adopt an analytical thinking style. Consistent with this claim, individuals from lower social classes consistently favour categorizations based on thematic rather than taxonomic relations and—at least for those in lower educational groups—use more dialectical reasoning (anticipating change). Moreover, they are less likely to sacrifice one person to save many in the trolley dilemma, which can also be interpreted as a more intuitive or less deliberative response, which is consistent with less analytical thinking62. Claim 2.3 is that individuals from lower social classes pay more attention to context. Inconsistent with this claim, we found that individuals from higher, not lower, social classes use more contextual explanations for life events and are more influenced by contextual information in an emotion appraisal task. Claim 2.4 is that individuals from lower social classes experience fewer self-oriented emotions and more other-oriented emotions. Inconsistent with this claim, we found that it is individuals from higher rather than lower social classes who report more other-oriented positive self-emotions, although they do report more self-oriented positive emotions (that is, contentment and pride). Moreover, they experience fewer negative self-conscious emotions. Together, these results indicate that individuals from higher social classes experience more pleasing emotions, regardless of whether these emotions are self- or other-oriented (lending further support to Claim 1.3 in terms of status). Claim 2.5 is that individuals from lower social classes are more prosocial. Inconsistent with this claim, we found that individuals from higher social classes are less likely to lie for career benefits. The idea that this prosociality among individuals from higher social classes is driven by self-interest is also unsupported, as their giving behaviour is not influenced by whether the context is private or public, and their unethical behaviour does not depend on whether the beneficiary is themselves or a friend. Upon exploring the main effect of social class on prosociality, we found that it varied on the basis of the specific indicator used and how prosociality was operationalized (lying, donating tickets or engaging in unethical behaviours). Similar inconsistencies are observed in the corpus of studies attempting to replicate the link between social class and prosociality63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84. In summary, among the five claims derived from the distinction between self-orientation and other and environment orientation, only the third claim about differences in cognitive style is supported by our data.

This conclusion raises questions about the validity of models in the psychology of social class that contrast psychological orientations towards ‘the self’ with those towards ‘others and the environment’. Our data suggest that such an opposition is not warranted: individuals from higher social classes seem to be more focused on both themselves and others than individuals from lower social classes. They exhibit both a more empowered self (for example, increased agency, self-esteem and risk-taking) and greater connection with others (for example, greater interdependence, greater appreciation of similarities, more supportive relationships, more prosocial behaviour, and greater love and compassion). We believe that these trends could be explained in a parsimonious way by differences in social class contexts with regard to constraints, uncertainty and status. Affluence, stability and high status may create a safer environment that encourages self-empowerment, challenge appraisals and eagerness, while still supporting open engagement with others. Conversely, scarcity, uncertainty and low status may give rise to a risk-laden environment that encourages self-preservation and threat appraisals, which potentially leads to distrust. Regarding the trends observed among individuals from higher social classes, other theoretical models support the idea that specific features of their environments may promote a focus on both the self and others. For instance, institutions such as higher education and the globalized marketplace promote individual autonomy and achievement, alongside a commitment to treating others as equal partners85. Regardless of the countries they reside in, individuals from higher social classes are more likely to spend time being socialized in these institutions and to adopt their norms6. As another example, individuals from higher social classes often find themselves in high relational mobility contexts, where they develop wider, looser and more far-reaching social networks (through travel, hobbies, occupations and studies)86. In such contexts, individuals grow accustomed to forming and breaking social bonds, making them experienced and motivated to attract others. This leads them to cultivate their individuality while remaining mindful of others87.

Cross-cultural differences

Our samples were drawn from four countries, which constrains our ability to fully explore cross-cultural differences. That said, it is important to note that while the replication analyses yielded relatively consistent results across countries, there were some notable exceptions in India. For example, social class was positively associated with sense of control in France, the USA and Switzerland, but negatively in India. Furthermore, social class was associated with interdependence only in the Indian sample. These variations may reflect genuine differences in how social class shapes control beliefs88 or self- and other-orientation89 between WEIRD and non-WEIRD contexts. Alternatively, these variations may be due to suboptimal data quality in India, where participants demonstrated markedly shorter median response times for inductions and low reliability for scales with reversed items (note that this latter issue may also be a cultural specificity in India, as it has been observed in other studies90,91). To better investigate the role of culture in social class, future research could use cross-national survey data with careful attention to data quality to systematically investigate how the effects of social class vary as a function of factors such as power distance92, cultural tightness–looseness93, WEIRDness41 and religiosity94.

Limitations

Several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the hypotheses examined were not selected from a random sample of papers but based on theoretical and feasibility reasons. Thus, our findings, including reproduction rates, cannot be generalized to the entire field. Second, we encountered several issues in the data collection process. In the Swiss, French and Indian samples, individuals in the lowest education group were underrepresented (by 6% to 16%). In Switzerland, the lower-than-expected response rate resulted in underpowered analyses for the longer tasks and experiments (see ‘Sampling plan’ in Methods). In India, difficulties in sample recruitment and issues with data quality necessitated ad hoc adjustments to the inclusion criteria (refer to ‘Sampling plan’ in Methods). Third, sense of power was included as an indicator of social class because it reflects the experience associated with high status. However, it is usually viewed as a distinct construct or potential mediator4,22,95. While we acknowledge these conceptual differences, our results indicate that sense of power produced similar effects to other indicators on most of the studied outcomes (though these effects were stronger).

Conclusion

In summary, a replication rate of 50% suggests that some aspects of the field are robust, whereas others are less so. Surprisingly, most results did not vary on the basis of the social class operationalization, suggesting that the flexible use of indicators may not be the main reason for such a suboptimal rate. Furthermore, most results were relatively consistent across national contexts, suggesting that cultural differences—while present—are not as impactful as might have been thought. Finally, half of the hypothesized effects were moderated by at least one of our three moderators, showing how identifying with one’s social class, feeling that society is fair or living in a place where class segmentation is more pronounced contributes to widening psychological differences between social classes.

From a theoretical perspective, hypotheses directly related to differences in social class contexts (in terms of constraints, uncertainty and status) tended to replicate well. These first-tier hypotheses form the basis of many theories of social class, and future research can continue to build on this foundation with relative confidence. However, hypotheses derived from models that contrast individuals from lower and higher social classes in terms of a general orientation (towards the self versus the other/the environment) have not replicated as successfully. Rather, our results suggest that individuals from higher social classes, compared with individuals from lower social classes, tend to be more focused on both themselves and others. This conclusion has the potential to reshape our understanding of the psychology of social class and merits further exploration.

Methods

Ethics information

The project was approved by the Research Ethics Board of the University of Lausanne (C_SSP_032020_00004). Participants gave their informed consent at the beginning of the study. Participants recruited by panel providers (US, French and Indian samples) received various types of compensation (for example, gift cards), whereas participants directly recruited by a local team (Swiss sample) participated in a lottery to receive gift cards.

Design

Selection of the studies

The studies were selected on the basis of a review conducted by the three authors. In June 2019, we used the reference lists of two recent reviews about the psychology of social class10,96 and further searched for empirical studies on a scientific publication search engine with three guiding criteria: the studies had to be theoretically relevant (testing a central claim of the various frameworks of the psychology of social class), cover a wide variety of domains (that is, self, cognition, emotion, relationships, decision-making and behaviour) and be feasible online. This process led to an initial selection of 21 studies. In December 2019, after securing funding for the project, we updated the list by searching for all new empirical studies that cited these 21 studies. To further ensure that we had not missed any important studies, when asking the authors of the original studies to review the protocol, we asked them to list findings they deemed important to replicate. This led us to remove one study and add two others.

Questionnaire

We invited the participants to complete an online questionnaire. Drawing on former large-scale replication initiatives41,97, we randomized the blocks of our questionnaire so that (1) the total duration would not exceed 20 min and (2) participants would not take part in more than one experiment. In addition to completing the nine measures of social class (~2 min), participants were randomly assigned to complete 2/3 of the short tasks or scales (~12–13 min) and 1/6 of the long tasks or experiments (~3–4 min). Two translation service companies translated the questionnaire from English into French (for the French and Swiss samples), Hindi (for the Indian sample), German and Italian (for the Swiss sample). The French, German and Italian versions of the questionnaire were double-checked by native speakers of each language.

Predictor variables

The participants first completed the nine measures of social class (for the country-based sample sizes, α values, means and standard deviations, see Supplementary Table 4; for the pooled within-country correlations, see Supplementary Table 10). The measures that were not used to build the quotas were counterbalanced (placed at the beginning of the questionnaire for half of the participants and at the end for the other half). As preregistered, for each hypothesis, we determined whether it was necessary to control for the order variable in a preliminary analysis (Supplementary Information, ‘General notes’, p. 20).

Education was measured using various categories for the highest level of education and combined into three groups representing the national population-based tertiles: (1) high school graduate or less versus two-year college degree versus four-year college degree or higher (US sample)98, (2) less than high school versus high-school graduate or two-year college degree versus three-year college degree or higher (French sample)99, (3) less than high school versus high school graduate versus some college or higher (Indian sample)100, and (4) less than high school versus high school and non-university diploma versus bachelor’s degree or higher (Swiss sample)101. For students, we used the highest level of education completed by either guardian. For all relevant analyses, education was contrast-coded. As preregistered, the planned contrast compared the lowest educational group to the highest educational group, but we used the codes −0.5 and +0.5 instead of −1 and +1 to facilitate interpretation of the estimates (that is, they represent the difference between the bottom and top groups).

Income was measured using bands corresponding to the national population-based household income deciles102,103,104,105. An open-ended question then asked participants to specify the exact amount of their household income. In the analysis, we used the response to the open-ended question or—if this response was missing or incoherent—the midpoint of the household income bands (see ‘Preregistration’). To adjust for household size, we used the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) square-root scale (that is, equivalizing income by dividing household income by the square root of household size)106.

Occupation was measured using Hoffmeyer-Zlotnik’s classification scheme107. After reporting their current employment status, self-employed participants indicated the size of their farm or business, whereas employed participants indicated the level of autonomy/complexity of their job. Participants were assigned to one of five occupational class categories (from 1 (unskilled, semiskilled, manual workers) to 5 (far-reaching leadership tasks and decision-making powers)). For retirees and students, we determined their former occupational class category or the category of the main earner in the family, respectively. Deviating from the preregistration, unemployed participants were assigned a score of zero to avoid excluding a full category of persons from the samples.

Subjective SES was measured using the MacArthur Scale18. The participants were presented with a ten-rung ladder representing “where people stand in (their) local community”. They were asked to indicate where they thought they stand on the ladder (from 1 (bottom) to 10 (top)).

Childhood subjective SES was measured using an adapted version of the MacArthur Scale108. This time, the participants were asked to indicate where they and their families stood on the ladder when they were five to ten years old (from 1 (bottom) to 10 (top)).

Childhood SES was measured using a three-item scale (for example, “I grew up in a relatively wealthy neighborhood”; from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree))3.

Social class self-categorization was measured by asking the participants to report their social class (from 1 (lower class) to 5 (upper class))109.

Financial scarcity was measured by asking the participants about the balance of their income and expenses (from 1 (saves a lot of money) to 5 (gets into debt); for evidence of the convergent validity of the instrument, see refs. 110,111).

Sense of power was measured using a three-item scale (for example, “I think I have a great deal of power”; from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree))22.

Outcome variables: self-reported scales or short tasks

The participants then completed 2/3 of the short tasks or scales (for the country-based sample sizes, α values, means and standard deviations, see Supplementary Table 5). Unless otherwise specified, the response scales ranged from 1 (strongly disagree (or not at all)) to 7 (strongly agree (or completely)). Items belonging to the same scale were presented in a random order.

The self. Sense of control (H1/H20) was measured using the 12-item Personal Mastery and Perceived Constraints Scale (for example, “What happens in my life is often beyond my control”)112. Agency (H2) was measured using the Agency Scale, which asks participants the extent to which five traits describe them (for example, “self-confident”)113. Persistence in goal striving (H3) was measured using the five-item Persistence in Goal Striving Scale (for example, “When I encounter problems, I don’t give up until I solve them”)114. Self-esteem (H4) was measured using the four-item Rosenberg Self-Esteem Short Scale (for example, “I take a positive attitude toward myself”)115. Narcissism (H5) was measured using the six-item Narcissistic Admiration and Rivalry Questionnaire Short Scale (for example, “Being a very special person gives me a lot of strength”)116. Entitlement (H6–7) was measured using the nine-item Psychological Entitlement Scale (for example, “I honestly feel I’m just more deserving than others”)117. Inter/independent self-construal (H8) was measured using an adaptation of Singelis’ Self-Construal Scale, which asks participants the extent to which ten independent (for example, “I always express my opinions clearly”) and ten interdependent (for example, “I am concerned about what people think of me”) statements describe them (from 1 (does not describe me at all) to 5 (describes me very much))16,118. Negative reactions to reduced individuation (H9) were measured using three questions that participants respond to by expressing whether they feel good or bad after imagining a friend purchasing the same car as them17.

Relationships. Chaos (versus stability) (H12–13), communal orientation (H12) and obsession with money (H13) were measured as follows: first, the participants chose between a chaotic (with ups and downs) and a stable (steadily increasing) graph to represent the expected trajectory of their future economic well-being; second, they completed the 13-item Communal Orientation Scale (for example, “I often go out of my way to help another person”; from 1 (extremely uncharacteristic of me) to 7 (extremely characteristic of me))119 and the five-item Obsession subscale of the Money Beliefs and Behavior Scale (for example, “I feel that money is the only thing that I can really count on”)120. The scales were presented in a random order. Education and ethnic/national biases (H14–16) were measured with thermometer ratings (from 0 (very cold) to 100 (very warm)) of seven groups (that is, more-educated versus less-educated people as well as five ethnic groups—four outgroups and one ingroup, adapted to the cultural context)19. In our preregistered study protocol, we planned to test the equivalence between education and ethnic/national biases (H16). However, owing to an unforeseen shortcoming in the translation of the questionnaire in both the French and Swiss versions, the measure of national ingroup attitude was mistakenly replaced with a measure of national outgroup attitude, meaning that H16 could not be tested in these two samples.

Cognition. Thematic/holistic and taxonomic/analytical thinking styles (H17) were measured using the triad task, which includes 14 lists of three objects (for example, cow, grass and chicken), each involving one thematic pair (cow/grass) and one taxonomic pair (cow/chicken); the participants had to indicate which two objects were more closely related16. Contextual explanations (H19–20) were measured using ratings of eight events (for example, “being laid off at work”) on a seven-point bipolar scale ranging from 1 (individual primarily responsible) to 7 (outside forces primarily responsible)11. Anticipation of change (H18) was measured with the estimated likelihood (in per cent) that contradictory events would happen in eight different situations (for example, “Two kids are fighting at kindergarten. How likely is it that they will become lovers some day?”)16.

Emotion. Other- and self-oriented positive emotions (H21–24) were measured using the 12-item Dispositional Positive Emotions Scale assessing feelings of contentment (for example, “I am generally a contented person”), pride (for example, “I take great pride in my achievements”), compassion (for example, “I am a very compassionate person”) and love (for example, “I grow to love people who are kind to me”)20. Influence of contextual emotional information (H26) was measured using 12 pictures with a central character showing an emotion (anger, happiness or sadness) and four background characters showing either the same emotion (three pictures) or a different emotion (nine pictures). For each picture, the participants rated the anger, happiness and sadness of the central character using scales ranging from 1 (not at all) to 10 (very much)11.

Social behaviour. Unethical behaviours (H27) were measured as follows. The participants were asked to take the role of an employer negotiating a salary with a job candidate seeking a long-term position. The participants were told that the job would be eliminated after six months, but they had strong incentives to fill the position. Afterwards, they reported as a percentage how likely they would be to hide the truth about the position from the candidate24.

Decision-making. Utilitarian moral decision-making (H35) was measured using the so-called footbridge dilemma. After reading a scenario about a trolley heading down the tracks towards five workmen, the participants had to indicate whether it was appropriate or not to push a stranger onto the tracks to stop the trolley from killing the five workmen27. The preregistered replication procedure of the original study involved measuring social class using perceived resource availability and examining how this predicted utilitarian moral decision-making (H35). However, owing to an unforeseen shortcoming in the questionnaire construction process in both the French and Swiss versions, the measure was mistakenly omitted, meaning that H35 could not be tested in the primary analysis for these two samples.

Outcome variables: experiments or longer tasks

After completing the self-report scales or short tasks, the participants were randomly assigned to one of the five experiments or the social network task (for the country-based sample sizes, α values, means and standard deviations, see Supplementary Table 5).

Relationships: social network task (H10–11). The participants were presented with three concentric circles centred on a small circle labelled “YOU”. First, we assessed the proportion of individuals in one’s inner circle. The participants were asked to report the initials of (1) the people to whom they are very close in the inner circle, (2) the people who are not so close but still important in the middle circle and (3) the people who are least important in the outer circle. Second, we assessed the social support received: the participants reported whether each of their network members showed more social support or annoyance16.

Emotion: self-conscious negative emotions (H25). First, the participants self-rated nine baseline emotions (that is, self-conscious negative emotions (embarrassment, fear, guilt and worry) and five other negative emotions; from 1 (not at all) to 8 (very much))21. Second, the participants played the recipient in the dictator game, with a bogus other allocating ten raffle tickets between themselves and the participant. They were randomly assigned to one of two between-participants conditions: (1) in the near-equal sharing condition, the bogus other shared four of the ten tickets with the participant, and (2) in the low sharing condition, the bogus other shared one ticket. Third, the participants again completed the emotion measures.

Social behaviour: unethical behaviours (H27). The participants were randomly assigned to one of two between-participants conditions: (1) in the self-benefit condition, they were asked the extent to which they would engage in eight unethical behaviours for their own benefit (from 1 (very unlikely) to 7 (very likely)), and (2) in the other-benefit condition, they were asked the extent to which they would engage in the same eight unethical behaviours for the benefit of a friend (using the same scale)22. ‘Self-beneficial’ was coded as +0.5, and ‘other-beneficial’ was coded as −0.5, contrary to the preregistration, which had the coding reversed.

Social behaviour: prosocial behaviour (H28). The participants were asked to play the dictator in the dictator game twice and allocate ten raffle tickets between themselves and a bogus other. Participants were assigned to the two within-participants conditions in a counterbalanced order: (1) in the private condition, they were instructed that their gift would be anonymous, and (2) in the public condition, they were instructed that their gift would be accompanied by identifying information (that is, name and city of residence). Prosocial behaviour was measured using the number of raffle tickets allocated to the bogus other23.

Decision-making: delayed reward and risk aversion (H30–33). The participants were randomly assigned to one of two between-participants conditions: (1) in the mortality condition, they read a text presenting the world as dangerous, and (2) in the control condition, they read a text about how to choose a rain jacket25. Preference for delayed reward was measured using seven hypothetical choices involving an increasing monetary reward for delayed options (for example, “Do you want to get $100 tomorrow or $110 90 days from now?” (with $10 increments)), and risk aversion was measured using seven hypothetical choices involving an increasing monetary reward for a guaranteed option compared to a 50% chance of getting a larger amount (for example, “Do you want a 50% chance of getting $800 OR [to] get $100 for sure?” (with $100 increments)). The order of presentation of the measures was counterbalanced.

Decision-making: cognitive performance (H34). The participants were randomly assigned to one of two between-participants conditions: (1) in the hard financial problems condition, they had to think about how to solve four financial problems involving large amounts of money, and (2) in the easy financial problems condition, they had to think about how to solve similar problems involving smaller amounts of money (the amounts of money were adapted to the standard of living in the national population)26. The participants were then instructed to keep thinking about the financial problems while performing three Raven’s Standard Progressive Matrices presented in a random order. Cognitive performance was measured using the number of matrices correctly solved. For each country, we pretested Raven’s Matrices (focusing on matrices of average difficulty according to the manual121) in a pilot study and selected three matrices that were correctly solved by approximately 50% of individuals. The details of these pilot studies can be found in the Supplementary Information (Table S-E5a, p. 31).

Moderators

At the beginning of the questionnaire, the participants filled out two scales used for the moderation analyses (that is, social class identification and system-justification beliefs) and provided information about their place of residence (which enabled us to link their responses to local data on income inequality). Social class identification was measured using a single-item scale asking the participants to rate the importance of their social class in describing them109. System-justification beliefs were measured using the four-item System Justification Scale (for example, “In general, I find society to be fair”)122. Local income inequality indicators were extracted from public economic data and merged with the survey data. We used the most recent local Gini coefficient estimates available at the lowest level of geographic aggregation. Specifically, we used the 2022 ACS-based zip-code-level Gini coefficients for the US sample123, the 2020 INSEE-based municipality-level Gini coefficients for the French sample124, the 2020 AFC-based municipality-level Gini coefficients for the Swiss sample125 and the 2012 NSSO-based district-level Gini coefficient for the Indian sample126.

Control variables