Abstract

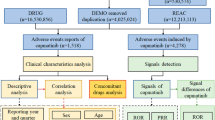

The use of complementary, alternative and integrative medicine (CAIM) is highly prevalent among autistic individuals, with up to 90% reporting having used CAIM at least once in their lifetime. However, the evidence base for the effects of CAIM for autism remains uncertain. Here, to fill this gap, we conducted an umbrella review of meta-analyses exploring the effects of CAIM in autism across the lifespan and developed a web platform to disseminate the generated results. Five databases were searched (up to 31 December 2023) for systematic reviews with meta-analyses exploring the effects of CAIM in autism. Independent pairs of investigators identified eligible papers and extracted relevant data. Included meta-analyses were reestimated using a consistent statistical approach, and their methodological quality was assessed with AMSTAR-2. The certainty of evidence generated by each meta-analysis was appraised using an algorithmic version of the GRADE framework. This process led to the identification of 53 meta-analytic reports, enabling us to conduct 248 meta-analyses exploring the effects of 19 CAIMs in autism. We found no high-quality evidence to support the efficacy of any CAIM for core or associated symptoms of autism. Although several CAIMs showed promising results, they were supported by very low-quality evidence. The safety of CAIMs has rarely been evaluated, making it a crucial area for future research. To support evidence-based consideration of CAIM interventions for autism, we developed an interactive platform that facilitates access to and interpretation of the present results (https://ebiact-database.com).

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Autism spectrum disorder, hereafter referred to as autism, is a neurodevelopmental condition characterized by impairments in communication and social interaction, as well as restricted, stereotyped and repetitive behaviours and/or interests, frequently associated with sensory differences, all of which interfere with quality of life1. Note that, recognizing the preference of most individuals with lived experience on the autism spectrum, this Article adopts identity-first language (for example, ‘autistic individuals’), which places references to the autism spectrum at the forefront of statements. We also acknowledge that some individuals diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder prefer person-first language, which prioritizes mentioning the person before the condition.

Interestingly, although not specifically designed for autism, many autistic individuals utilize complementary, alternative and integrative medicine (CAIM)2. Several factors may contribute to this choice. For example, personal values, the perceived lack of efficacy of conventional interventions, and challenges in accessing or implementing traditional interventions may all encourage engagement with the use of CAIM3,4,5. Despite the absence of a universally accepted definition of CAIM, the Cochrane Collaboration has proposed a widely used operational definition, which uses three principal criteria for classification6,7. First, it considers whether the intervention originates from a medical system outside the Western allopathic model (that is, considered traditional), thereby including practices such as Chinese medicine. Second, it evaluates whether the intervention is regarded as a standard treatment for a specific condition within the Western allopathic framework. Third, the context in which the intervention is delivered is examined; interventions that are self-administered or provided by practitioners outside conventional medical institutions are more likely to be classified as CAIM. It is important to note that this definition does not incorporate scientific evidence about efficacy as a criterion, thus allowing for the possibility that a CAIM intervention may be supported by robust scientific evidence regarding its effects, although this is not currently the case in the autism literature as our work shows.

The median prevalence of use of any CAIM among autistic people is 54%, with some studies finding a lifetime prevalence as high as 92% (ref. 2). This high level of use is explained by a generally positive public perception of the safety and efficacy of CAIM8,9. However, many studies and international clinical guidelines indicate a lack of efficacy—and, in some cases, adverse events—for this type of intervention in autism10,11. In this perspective, parents of autistic children have identified challenges in navigating the scientific literature on the efficacy/effectiveness and safety of CAIM in autism. In particular, they have highlighted the need for a reliable resource that effectively disseminates this scientific information in an accessible manner, to make informed decisions about the use of CAIM12. Therefore, there is an urgent need to synthesize all available evidence on the efficacy and safety of CAIM for autistic individuals and to make this information easily accessible to the wider community, including health professionals, to foster evidence-based shared decision-making. The need for such a tool is reinforced by the positive outcomes of decision-aid tools developed in other fields13.

Currently, many meta-analyses on CAIM for autism are available, but it is not uncommon for them to show divergent results regarding the effect of the same intervention for the same clinical population14. These discrepancies, which can be caused by different inclusion criteria but also data analysis error or other methodological issues15, leave decision-makers, clinicians and individuals with lived experience alike facing conflicting information about the effects of the available interventions. Umbrella reviews are a form of evidence synthesis that addresses this issue by quantitatively synthesizing the information generated by all systematic reviews and meta-analyses on a broad topic, appraising their methodological quality and providing an assessment of the strength and/or quality of the evidence16,17. In other words, while the unit of inclusion of systematic reviews and meta-analyses consists of individual primary studies, the unit of inclusion of umbrella reviews consists of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Umbrella reviews can thus inform clinical decision-makers on the current best secondary, high-level evidence relevant to a specific topic.

In this Article, we conducted an umbrella review investigating the efficacy and safety of CAIMs in autistic individuals. Then, in line with the needs recently expressed by stakeholders12, we developed an open-access, interactive online resource (named Evidence-Based Interventions for Autism: Clinical Trials (EBIA-CT), freely accessible at https://ebiact-database.com/) allowing user-friendly access to the results of the umbrella review for each identified participants–intervention–comparator–outcome (PICO). This work adheres to the Umbrella-Review, Evaluation, Analysis, and Communication Hub (U-REACH) framework18. The evidence summarized on this website is intended for informational purposes only and should not be used as a replacement for professional medical advice. We strongly recommend that any discussion of these findings be undertaken in consultation with a qualified healthcare provider who is able to assess and appreciate individual clinical circumstances.

Results

Results of the searches

From our initial search, which yielded 7,051 potentially relevant publications (5,702 after removing duplicates), we selected 201 for full-text review and identified 72 meta-analytic reports that met our eligibility criteria (Fig. 1). We then excluded 19 meta-analytic reports: 7 lacked information necessary to replicate calculations, and 12 contained actual or probable data analysis errors. This resulted in a final set of 53 meta-analytic reports included in our analyses. These publications contained a total of 248 different meta-analyses, with each meta-analysis covering a specific combination of PICOs. For example, a single publication could contain several separate meta-analyses examining how the same intervention affects different age groups or different outcomes. Supplementary Information sections 9 and 10 provide full lists of the 53 included and 148 excluded publications.

Characteristics of the meta-analytic reports retained in the umbrella review

The 53 retained meta-analytic reports examined the effects of at least one of the 19 intervention types (with descriptions of each of them publicly available at https://ebiact-database.com/interventions/) and on at least one of the 19 possible outcomes and were mainly (87%) published after 2018. The 248 meta-analyses synthesized the evidence of more than 200 controlled clinical trials (CCTs) and 10,000 autistic participants and explored 138 unique PICOs. A total of 53 PICOs (38%) were explored in several overlapping meta-analyses. The PICOs with the highest number of overlapping meta-analyses investigated the effects of polyunsaturated fatty acids on disruptive behaviours and social-communication impairment.

Description of the meta-analyses included in the primary analysis

A total of 138 meta-analyses, derived from 27 reports, were finally included in the primary analysis after discarding overlapping meta-analyses. According to the A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews-2 (AMSTAR-2) scoring, 23 PICOs were evaluated by meta-analyses of high quality (17%), 87 by meta-analyses of low quality (63%) and 28 by meta-analyses of critically low quality (20%). The median number of clinical trials per meta-analysis was 3, and the median number of participants per meta-analysis was 152, with a median percentage of female participants of 14%. A total of 25 meta-analyses (18%) involved very young children, 85 (62%) included school-aged children, 17 (12%) involved adolescents and 11 (8%) focused on adults.

Results of our primary analysis

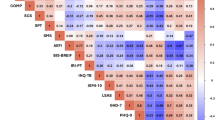

This section presents meta-analytic results for the primary and secondary outcomes, highlighting findings with a moderate Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) rating as well as those that exhibit statistically significant and large pooled effect sizes. The GRADE framework assesses the overall quality of evidence supporting meta-analytic estimates based on five criteria: risk of bias of included clinical trials, heterogeneity, publication bias, indirectness and imprecision19 (see details in ‘Assessment of the levels of evidence’ section in the Methods). Higher GRADE ratings thus indicate better quality of evidence. Complete results are visually summarized in Figs. 2 and 3 and detailed in Supplementary Information section 11.

Scatter plot indicating, for each PICO combination, the magnitude of the pooled effect sizes (grey: absence of effect (SMD ranging from −0.20 to 0.20, OR/RR ranging from 0.80 to 1.25); green: positive effect; red: negative effect; darker colour indicates larger magnitude), the statistical significance (black stars indicate a two-sided P value <0.05), the confidence GRADE rating (no surrounding circle: ‘very low’; light circle: ‘low’; bold circle: ‘moderate’) and the size of the meta-analysis (greater dot width indicates larger meta-analysis). All pooled effect sizes were estimated using random-effects meta-analysis, with no adjustment for multiple testing.

Scatter plot indicating, for each PICO combination, the magnitude of the pooled effect sizes (grey: absence of effect (SMD ranging from −0.20 to 0.20, OR/RR ranging from 0.80 to 1.25); green: positive effect; red: negative effect; darker colour indicates larger magnitude), the statistical significance (black stars indicate a two-sided P value <0.05), the confidence GRADE rating (no surrounding circle: ‘very low’; light circle: ‘low’; bold circle: ‘moderate’) and the size of the meta-analysis (greater dot width indicates larger meta-analysis). All pooled effect sizes were estimated using random-effects meta-analysis, with no adjustment for multiple testing.

Main outcomes

We found that oxytocin was the intervention with the highest levels of evidence (that is, the highest GRADE ratings) across all outcomes and age groups (Fig. 2). This intervention demonstrated negligible and not statistically significant efficacy for core autism symptoms across childhood and adulthood (all pooled standardized mean differences (SMDs) ranging from −0.04 to 0.06, and all P values exceeding 0.05; all GRADE ratings: from ‘very low’ to ‘moderate’), except for restricted/repetitive behaviours in adults, where a small effect size was found (SMD 0.404, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.166–0.643; GRADE: ‘moderate’). There were no significant concerns about the acceptability, tolerability or adverse events of oxytocin (all pooled risk ratios (RRs) ranging from 0.72 to 1.30, and all P values >0.05; all GRADE ratings: from ‘very low’ to ‘moderate’). The only other effect supported by at least moderate levels of evidence for any of our primary outcomes was the consumption of polyunsaturated fatty acids in school-age children, which was not significantly associated with the occurrence of adverse events (RR 0.676, 95% CI 0.356–1.281; GRADE: ‘moderate’) and did not yield large effects on core autism symptoms (all pooled SMD values <0.50; all GRADE ratings: ‘very low’ or ‘low’).

Notably, a number of interventions demonstrated large effect sizes (SMD ≥0.80) and reached statistical significance, but they were systematically supported by very low levels of evidence. In school-age children, these included music therapy (SMD 0.835, 95% CI 0.316–1.355), animal-assisted interventions (SMD 0.934, 95% CI 0.354–1.515) and transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) (SMD 0.844, 95% CI 0.016–1.672) for reducing overall autism symptoms. In adolescents, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) appeared to have a large efficacy on restricted/repetitive behaviours (SMD 0.899, 95% CI 0.529–1.269). In adults, physical activity demonstrated potential benefits for social-communication (SMD 0.874, 95% CI 0.486–1.263). Importantly, acceptability, tolerability or adverse events were not evaluated for these interventions.

Secondary outcomes

As illustrated in Fig. 3, no intervention presented statistically significant results supported by at least low levels of evidence for the secondary outcomes. Again, several interventions demonstrated large effect sizes with statistical significance, although supported by only very low levels of evidence. In school-age children, melatonin showed promise for improving sleep quality (SMD 1.124, 95% CI 0.349–1.898) and quantity (SMD 1.080, 95% CI 0.413–1.747), while in adolescents rTMS showed promise for reducing disruptive behaviours (SMD 0.940, 95% CI 0.570–1.310). Notably, no statistically significant increase risks in safety outcomes were observed among school-age children using melatonin (with RR values ranging from 0.84 to 1.75 and all P values exceeding 0.05; all GRADE ratings: ‘very low’), and safety was not assessed for rTMS use in adolescents.

Overlapping meta-analyses and EBIA-CT online platform

Among the 53 PICOs that were explored by at least 2 overlapping meta-analyses, the median overlap of the 95% CI of the pooled effect sizes was 50% (Supplementary Information section 12). Only 33 (63%) of PICOs consistently achieved a similar GRADE rating, and only 35 (66%) consistently achieved a similar statistical significance status. Among the PICOs with statistically significant results in our primary analysis and at least one overlapping meta-analysis, we found that ten (62%) presented at least one overlapping meta-analysis with non-statistically significant results. Last, we found that eight PICOs presented a large discrepancy, which we characterized as a substantial difference in either (1) the magnitude of the overlapping estimated effects (that is, the existence of two pooled effect sizes varying by more than SMD ≥0.30 with different statistical significance status, or an average overlap of the 95% CI <20%) or (2) the GRADE status (differing by two points). On the EBIA-CT platform, we enable users to avoid these inconsistencies by systematically presenting the results of the best current scientific evidence, making this platform a convenient hub for the highest-quality scientific evidence.

Discussion

We conducted a review of the effects of CAIM in autistic individuals, analysing 248 meta-analyses including 200 clinical trials involving over 10,000 participants. Based on this synthesis, we created an interactive user-friendly online platform aimed at disseminating scientific evidence in an accessible format to support healthcare professionals, individuals with lived experience and their families in making informed decisions about CAIM.

Among interventions with an efficacy supported by at least moderate levels of quality of the evidence, only oxytocin showed—for one outcome in one age group—a statistically significant but small effect (SMD <0.50). Several interventions (animal-assisted interventions, melatonin, music therapy, physical activity, rTMS and tDCS) presented statistically significant results with a very large effect size, but the quality of the evidence underpinning the estimation of these effects was very low. The two main factors responsible for these low levels of evidence were imprecision (namely the low number of participants included in a meta-analysis and/or a very wide pooled 95% CI) or limitations (namely the presence of studies at high risk of bias). This finding highlights the need to improve the methodological rigour in the field, to enable a more precise evaluation of the impact of CAIM interventions. In particular, further research on CAIM interventions requires adequately powered studies to precisely estimate their effects while implementing rigorous methodological controls to minimize potential sources of bias. For instance, although blinding may be challenging for outcomes based on daily life reports (for example, quality of life), emerging tools—such as the Brief Observation of Social Communication Change—are being developed to enable blinded assessments of key outcomes in ASD, addressing the limitations inherent in traditional instruments such as the Social Responsiveness Scale and the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale. In addition to the generally small effect sizes and low levels of evidence supporting most CAIMs, a critical finding was that safety assessments were missing for most interventions, with less than half of identified CAIMs having any evaluation of acceptability, tolerability or adverse events. This knowledge gap is particularly concerning for interventions with potential adverse effects (such as secretin administration) and represents a major public health challenge given the high frequency of CAIM use in this population2. In our view, a key direction for future randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and observational studies will be to explore the safety of CAIMs in autism.

The findings of this study address a critical knowledge gap in the literature regarding CAIM interventions for autism by synthesizing evidence from a substantial body of research previously available in fragmented form only. Previous reviews have typically focused on specific intervention types and did not assess the quality of the generated body of evidence20,21,22. Our approach enables mapping of the evidence across the full spectrum of CAIMs. Notably, the umbrella review methodology used does not allow us to compare efficacy among included interventions (unlike network meta-analyses). However, our umbrella review does establish a unified evidence grading system that allows stakeholders to evaluate the state of evidence for each intervention using consistent, transparent and objective criteria. Moreover, the interactive platform developed addresses the needs from the autism community and the documented disparity between research production and knowledge translation identified by previous studies12,23,24. Clinicians and autistic people and their families can collaboratively use this resource to navigate the available evidence for each intervention, including its inherent limitations and the prevailing uncertainty regarding harms, to inform their perspectives about CAIM25. This facilitates informed decisions that are tailored to individual needs, preferences and circumstances26,27.

From a methodological standpoint, our study revealed a high prevalence of overlapping meta-analyses examining identical populations, interventions, and outcomes. While overlapping analyses can provide valuable independent replication, they often yield inconsistent results. This aligns with previous findings15,28,29,30 and underscores the challenge for healthcare professionals to stay abreast of the best evidence. These inconsistent results are primarily due to differences in the identification of primary studies and the choice of the outcome measure to estimate the effect sizes. Interestingly, our assessment of the quality of the meta-analyses indicated that incomplete searches (which may result in the identification of only a subset of relevant primary studies) and lack of preregistration (which may lead to arbitrary post-hoc decisions about the optimal outcome measure for measuring a given outcome) were among the most common biases observed in the meta-analyses. This suggests that improving key aspects of the meta-analytic methodology (namely adherence to standardized database search guidelines and the development of a protocol before conducting a meta-analysis) may be a promising way to reduce result variability across independent meta-analyses17.

The present work should be interpreted in light of its limitations. First, a key methodological decision we made was to assess the levels of evidence using an algorithmic version of the GRADE framework, departing from its original subjective approach. However, as the objective of our work is not to make recommendations, which require subjectivity and are context dependent, we elected to remove the subjectivity from our grading process. This decision aligns with previous large umbrella reviews31 and with the typical grading process in network meta-analyses32. The algorithmic GRADE assessment used in this Article—based on criteria established in previous studies and developed separately from the present work32,33,34—provides readers with a context-independent algorithmic evaluation of the quality of the evidence, synthesizing a substantial amount of information from each meta-analysis. Second, our analysis was limited to standard pairwise meta-analytic models, which precluded us from making statistical comparisons of the effects of different intervention on the same outcome, or of the effect a single intervention on multiple outcomes. Our choice of extracting clinical trial-level data could have theoretically enabled the use of more advanced meta-analytic models—such as multivariate meta-analysis or network meta-analysis. However, these approaches rely on the critical assumption of transitivity. The substantial methodological heterogeneity across trials in our umbrella review (particularly regarding comparator types, which included placebo, treatment as usual, non-therapeutic interventions and others) meant this assumption could not be reasonably met without proper experimental verification35. Such verifications typically extend beyond the scope of umbrella reviews. By maintaining a PICO-level analysis, we adhered to best recommended practices in umbrella reviews prioritizing transparency, interpretability and methodological rigour36. Nevertheless, we acknowledge that this approach has inherent limitations, particularly its inability to facilitate comparisons within or between intervention effects. Future research could build on our umbrella review dataset to explore methodological strategies for addressing comparator-related heterogeneity. Such efforts could ultimately inform the feasibility of applying advanced statistical models in this emerging field of evidence synthesis.

In conclusion, this study provides the community with accessible scientific evidence regarding CAIMs for autism, highlighting the current lack of adequate evidence supporting their efficacy and safety. Many studies have examined the effects of various CAIMs for autistic people, but the quality of the evidence generated by these studies is mostly poor. This may lead to imprecise and/or biased estimates of effects. The field requires well-designed, adequately powered RCTs using standardized outcome measures and incorporating comprehensive safety monitoring to facilitate a more nuanced understanding of the benefits and harms associated with each CAIM in the context of autism. Our umbrella review and related platform will be updated on a regular basis to capture the evolution of the evidence in this field. To further enhance the content and features of this platform, future umbrella reviews will be conducted to complete the database (for example, an umbrella review of pharmacological interventions), and collaborative studies will be conducted with healthcare professionals and individuals with lived experience to ensure that the platform meets their needs. Ultimately, the impact of the platform on clinical decision-making will be tested in randomized studies.

Methods

The umbrella review, based on a publicly available protocol (PROSPERO CRD42022296284), was conducted and reported according to relevant guidelines16,17,36, including the U-REACH methodological guidelines18 and the Preferred Reporting Items for Overviews of Reviews (PRIOR) reporting guidelines37. The PRIOR checklist is available in Supplementary Information section 1.

Search strategy and eligibility criteria

We searched MEDLINE, Web of Science, Embase, CINAHL and PsycINFO with terms related to two constructs (‘autism’ and ‘meta-analysis’), with no language, publication type or date of publication restrictions, up to 31 December 2023. The list of full search terms is reported in Supplementary Information section 2. Screening of the titles and abstracts, as well as study selection, was performed independently by the first author and several members of the team. Disagreements were resolved by the senior authors (R.D., S.C. and M.S.). References of included studies and Google Scholar were searched to identify additional eligible references, but all relevant reports found with these manual searches were already included in the database searches.

We included systematic reviews coupled with a meta-analysis of both randomized and non-randomized CCTs that assessed the efficacy of any CAIM on both core autism symptoms and key autism-related symptoms in autistic participants of any age. Contrary to what was envisioned in the protocol, we chose to include both randomized and non-randomized controlled trials, rather than including only randomized controlled trials. This choice was made because, in the field of autism, several promising types of intervention—such as long-term or intensive interventions—are difficult to assess in randomized trials. This choice ensures a complete and consistent mapping of the literature regardless of the intervention type. Even if less than 10% of studies were non-randomized studies in our primary analysis, we performed a sensitivity analysis restricted to randomized clinical trials.

A review was considered ‘systematic’ if it was identified as such by its authors and searched at least two scientific databases in combination with explicit inclusion and exclusion criteria. The definition of autism followed that used by primary authors, typically in line with international classifications (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders from 3rd to 5th editions, or International Classification of Diseases (ICD) 9 or 10). Based on the mean age of the participants within each meta-analysis, we grouped the presentation of the results into four distinct age groups: (1) preschool children (mean age ranging from 0 to 5 years), (2) school-aged children (6–12 years), (3) adolescents (13–19 years), and (iv) adults (≥20 years). For each meta-analysis, we evaluated whether the average age of the participants from the different CCTs was homogeneous (see our exact criteria in Supplementary Information section 3).

In accordance with the standard classification of the National Institutes of Health National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine6,7, we identified 19 CAIM types (see the list and complete description at https://ebiact-database.com/interventions/). The prespecified primary outcomes of interest were autism core symptoms (overall symptoms, social communication impairment, restricted/stereotyped/repetitive behaviours and sensory peculiarities) and CAIM-related safety (acceptability (risk of all-cause discontinuation), tolerability (risk of discontinuation due to treatment-related adverse events) and adverse events (risk of experiencing at least one or any specific adverse events)). Secondary outcomes were language skills (overall language, receptive language and expressive language), functioning (overall cognitive functioning, adaptive behaviours and quality of life), disruptive behaviours and psychiatric comorbidities (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), anxiety and emotional/depressive symptoms). We included sleep quality and quantity as post-hoc outcomes, given the significance of sleep for autistic individuals and their families that emerged from the screened papers38.

Data extraction and checking

As described in detail in Supplementary Information section 4, we extracted information regarding the characteristics of clinical trials (for example, risk of bias), participants (for example, mean age) and interventions (for example, dosage) from meta-analytic reports. In instances where the age of the participants was not reported in the meta-analysis, we obtained this directly from the report describing the clinical trial. Similarly, when the estimated effect sizes of individual studies were deemed unplausible (for example, SMD ≥5), we conducted the necessary checks using the metaConvert R package (version 1.0.2)39 and excluded meta-analyses containing inaccuracies or errors. More details on data extraction and data quality checks are available in Supplementary Information sections 4 and 5.

Assessment of the methodological quality

In line with recommendations for umbrella reviews16,17,18,36, we obtained the quality of primary studies by extracting this information directly from the meta-analytic reports. We evaluated the quality of the meta-analyses using the AMSTAR-2 tool40. The AMSTAR-2 scoring was performed independently by the first author and several members of the team.

Overlapping meta-analyses

Following the identification of several overlapping meta-analyses, that is, independent meta-analyses that assessed the same PICO combination, the most recent meta-analysis with the highest methodological quality was selected for the primary analysis, rather than the largest meta-analysis (see more details in ‘Main deviations from the protocol’ section). Then, we assessed the concordance of the results of overlapping meta-analyses, such as the percentage overlap of the 95% CI around the pooled effect size or the agreement on the GRADE ranking, in a secondary analysis. More details on the selection process for overlapping meta-analyses are available in Supplementary Information section 6.

Assessment of the levels of evidence

When registering the protocol, we did not describe any specific system for assessing the levels of evidence regarding the effects of each intervention. This was because, at that time, there was no consensus on the best approach in umbrella reviews of RCTs, given that the traditional gold-standard framework for meta-analyses of interventions (the GRADE framework) becomes difficult to use when the number of comparisons to grade is high. In this Article, we chose to rely on the algorithmic version of the GRADE framework recently implemented in the metaumbrella R software. These criteria are inspired by standard guidelines for rating the levels of evidence in large evidence syntheses, such as Confidence in Network Meta-Analysis (CINeMA)32. For all meta-analyses, the levels of evidence started with a ‘high’ ranking and could then be downgraded depending on the presence of risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision and publication bias (Table 1).

Development and update of the EBIA-CT platform

To tackle the recognized gap between scientific evidence about CAIM in autism and its accessibility for clinicians and both autistic persons and their families, we developed the EBIA-CT platform (https://ebiact-database.com/) to disseminate our results in a user-friendly manner. Building upon a preliminary version created during our prior work on psychosocial interventions15, we significantly enhanced the platform design and features during this project. This improvement process was informed by qualitative feedback from clinicians, stakeholders and researchers, ensuring the platform is user-friendly and effectively disseminates the findings of this umbrella review. Integrating the EBIA-CT platform into our umbrella review methodology allowed us to proactively adhere to the U-REACH guidelines, a framework specifically designed to promote the wide dissemination of umbrella review results. Furthermore, the platform is designed as a ‘living resource’, with planned annual updates for 5 years, following our established methodology and aligning with living review principles. In terms of ethical considerations, no new primary data were collected for this umbrella review or platform development. Therefore, formal ethics committee consultation was not deemed necessary, as is standard practice for projects focused on synthesizing and disseminating existing research findings. The platform is organized into three main sections:

-

(1)

Interventions: This section provides comprehensive details about each intervention we identified, including the target population (for example, age range and cognitive functioning level), implementation guidelines and meta-analysis results across age groups. It serves as a valuable resource for autistic individuals and their families seeking information on specific interventions.

-

(2)

Preferences: In this section, users can explore age-specific intervention outcomes, providing an overall mapping of the efficacy and safety of all interventions. This section supports informed discussions between clinicians and autistic individuals or their families, facilitating evidence-based decision-making tailored to individual needs.

-

(3)

Database: This section provides an overview of the information stored in the platform, and grants access to the raw data from the umbrella review, enabling users to download datasets for external analysis. It is especially useful for researchers identifying knowledge gaps and for guideline developers formulating recommendations.

Data analysis

As described in more detail in Supplementary Information section 7, all analyses were performed in the R environment (version 4.1.1) using the ‘metaumbrella’ package (version 1.1.0)41. We used the SMD as the main effect size measure for the assessment of efficacy, and the RR as the main effect size measure for the assessment of safety (that is, acceptability, tolerability and adverse events). Although we preregistered that the effect measure would be SMD only, we preferred analysing these safety outcomes on their natural effect measures, given their dichotomous nature. For meta-analyses of mean difference and OR, we converted this information for each trial to SMD (respectively RR) before conducting the calculations. Regardless of the metric used (RR or SMD), the direction of the effect was reversed when needed, such that a positive effect size (RR >1 or SMD >0) systematically reflected an improvement, that is, a symptom reduction, a competence improvement or a high safety.

We reran each meta-analysis identified in the review, to ensure consistent calculations and assessments of the level of evidence across meta-analyses. We systematically used a random-effects model with a restricted maximum likelihood estimator, or a Paul–Mandel estimator for τ2. The CI for the pooled effect size was based on the standard normal quantile method. The I2, Q statistics and τ2 statistics, as well as the 95% prediction interval, were used to assess heterogeneity. Egger’s regression asymmetry, the excess of statistical significance bias test and the proportion of participants in studies at high risk of reporting bias were used to examine the presence of small study effects42,43. When meta-analyses contained dependent effect sizes, we removed this dependence using the standard aggregating approach proposed by Borenstein and colleagues44 (Supplementary Information section 8). Because we chose to include both randomized and non-randomized studies, we conducted a sensitivity analysis restricted to randomized controlled trials. However, less than 10% of studies were non-randomized studies in our primary analysis, and the results of this analysis were very similar to those reported in the main manuscript.

Main deviations from the protocol

We made two important changes to our preregistered protocol. Although we initially planned to select the largest meta-analyses in cases of overlap, we ultimately prioritized the meta-analysis with the highest methodological quality—in line with our willingness to prioritize high-quality evidence for clinical decision-making. In addition, because the methodological landscape of umbrella reviews was still evolving at the time of registration and there were no gold-standard methods for assessing the quality of a very large body of evidence coming from umbrella reviews of RCTs, we did not prespecify an evidence grading system in our protocol. Instead, we relied on recent algorithmic GRADE criteria that have been proposed independently of the current work and implemented in the main umbrella review software34. Although these departures were made to increase methodological rigour, they represent post-hoc decisions that should be taken into account when interpreting our results and reflect the recent nature of the field of umbrella reviews.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are publicly available via GitHub at https://github.com/CorentinJGosling/EBIACT_CAM_2024.

Code availability

Additional information on the results and R code supporting data analysis is publicly available at https://corentinjgosling.github.io/EBIACT_CAM_2024.

References

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th edn (American Psychiatric Association, 2013); https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

Höfer, J., Hoffmann, F. & Bachmann, C. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review. Autism 21, 387–402 (2017).

Shepherd, D. et al. Documenting and understanding parent’s intervention choices for their child with autism spectrum disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 48, 988–1001 (2018).

Edwards, A. G., Brebner, C. M., McCormack, P. F. & MacDougall, C. J. From ‘parent’ to ‘expert’: how parents of children with autism spectrum disorder make decisions about which intervention approaches to access. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 48, 2122–2138 (2018).

Carlon, S., Carter, M. & Stephenson, J. A review of declared factors identified by parents of children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) in making intervention decisions. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 7, 369–381 (2013).

Wieland, L. S., Manheimer, E. & Berman, B. M. Development and classification of an operational definition of complementary and alternative medicine for the Cochrane collaboration. Altern. Ther. Health Med. 17, 50–59 (2011).

Ng, J. Y. et al. Operational definition of complementary, alternative, and integrative medicine derived from a systematic search. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 22, 104 (2022).

Odegard, B. R. et al. A qualitative investigation of the perceptions of complementary and alternative medicine among adults in Hawaiʻi. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 22, 128 (2022).

Hanson, E. et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine among children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 37, 628–636 (2007).

Autism Spectrum Disorder in Under 19s: Support and Management. NICE Guideline No. 170 (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2019); https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg170/chapter/recommendations

État des connaissances hors mécanismes physiopathologiques, psychopathologiques et recherche fondamentale (Haute Autorité de Santé Autisme et autres troubles envahissants du développement, 2012).

Smith, C. A. et al. Parents’ experiences of information-seeking and decision-making regarding complementary medicine for children with autism spectrum disorder: a qualitative study. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 20, 4 (2020).

Stacey, D. et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 4, CD001431 (2024).

Reichow, B. Overview of meta-analyses on early intensive behavioral intervention for young children with autism spectrum disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 42, 512–520 (2012).

Gosling, C. J. et al. Efficacy of psychosocial interventions for autism spectrum disorder: an umbrella review. Mol. Psychiatry 27, 3647–3656 (2022).

Fusar-Poli, P. & Radua, J. Ten simple rules for conducting umbrella reviews. Evid. Based Ment. Health 21, 95–100 (2018).

Ioannidis, J. P. Integration of evidence from multiple meta-analyses: a primer on umbrella reviews, treatment networks and multiple treatments meta-analyses. CMAJ 181, 488–493 (2009).

Gosling, C. J. et al. Umbrella-Review, Evaluation, Analysis and Communication Hub (U-REACH): a novel living umbrella review knowledge translation approach. BMJ Ment. Health 27, e301310 (2024).

Guyatt, G. H. et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Br. Med. J. 336, 924–926 (2008).

Sandbank, M. et al. Project AIM: autism intervention meta-analysis for studies of young children. Psychol. Bull. 146, 1–29 (2020).

Fraguas, D. et al. Dietary interventions for autism spectrum disorder: a meta-review. Nutrients 11, 2783 (2019).

French, L. & Kennedy, E. M. M. Annual Research Review: early intervention for infants and young children with, or at-risk of, autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 59, 444–456 (2018).

Pellicano, E., Dinsmore, A. & Charman, T. What should autism research focus upon? Community views and priorities from the United Kingdom. Autism 18, 756–770 (2014).

Fletcher-Watson, S. et al. Making the future together: shaping autism research through meaningful participation. Autism 23, 943–953 (2019).

Nicolaidis, C. et al. The AASPIRE practice-based guidelines for the inclusion of autistic adults in research as co-researchers and study participants. Autism 23, 2007–2019 (2019).

Maye, M., Sanon, V. & Caldwell, J. Shared decision-making in ASD care: broadening access and promoting personalization. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 42, 454–460 (2021).

Levy, S. E. et al. Shared decision making and treatment decisions for young children with autism spectrum disorder. Acad Pediatr. 16, 571–578 (2016).

Bottema-Beutel, K., Crowley, S., Sandbank, M. & Woynaroski, T. G. Adverse event reporting in intervention research for young autistic children. Autism 25, 322–335 (2021).

Ioannidis, J. P. The mass production of redundant, misleading, and conflicted systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Milbank Q. 94, 485–514 (2016).

Hoffmann, F. et al. Nearly 80 systematic reviews were published each day: observational study on trends in epidemiology and reporting over the years 2000–2019. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 138, 1–11 (2021).

Solmi, M. et al. Balancing risks and benefits of cannabis use: umbrella review of meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials and observational studies. Br. Med. J. 382, e072348 (2023).

Nikolakopoulou, A. et al. CINeMA: An approach for assessing confidence in the results of a network meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 17, e1003082 (2020).

Pollock, A. et al. An algorithm was developed to assign GRADE levels of evidence to comparisons within systematic reviews. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 70, 106–110 (2016).

Gosling, C. J., Solanes, A., Fusar-Poli, P. & Radua, J. metaumbrella: Umbrella Review Package for R; R package version 1.1.0. R Project https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/metaConvert (2025).

Siafis, S. et al. Placebo response in pharmacological and dietary supplement trials of autism spectrum disorder (ASD): systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Mol. Autism 11, 66 (2020).

Belbasis, L., Bellou, V. & Ioannidis, J. P. A. Conducting umbrella reviews. BMJ Med. 1, e000071 (2022).

Gates, M. et al. Reporting guideline for overviews of reviews of healthcare interventions: development of the PRIOR statement. Br. Med. J. 378, e070849 (2022).

McConachie, H. et al. Parents suggest which indicators of progress and outcomes should be measured in young children with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev. Disord. 48, 1041–1051 (2018).

Gosling, C. J. et al. metaConvert: an automatic suite for estimation of 11 different effect size measures and flexible conversion across them. Res. Synth. Methods 16, 575–586 (2025).

Shea, B. J. et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. Br. Med. J. 358, j4008 (2017).

Gosling, C. J., Solanes, A., Fusar-Poli, P. & Radua, J. metaumbrella: the first comprehensive suite to perform data analysis in umbrella reviews with stratification of the evidence. BMJ Ment. Health 26, e300534 (2023).

Egger, M., Davey Smith, G., Schneider, M. & Minder, C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Br. Med. J. 315, 629–634 (1997).

Stanley, T. D., Doucouliagos, H., Ioannidis, J. P. A. & Carter, E. C. Detecting publication selection bias through excess statistical significance. Res. Synth. Methods 12, 776–795 (2021).

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P. & Rothstein, H. R. Introduction to Meta-Analysis (John Wiley & Sons, 2021).

Acknowledgements

This work has been carried out within the framework of the ANR-23-CE28-0019-01 EBIA-CT awarded to C.J.G. and supported by the French National Research Agency and the France 2030 programme, under reference ANR-23-IAIIU-0010 awarded to C.J.G. and R.D. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript. We thank all the colleagues and their team who agreed to prepare and share their raw data, enabling the replication of their meta-analytic work (including Y. Li, P. Salazar de Pablo, K. Gurusamy and D. Fraguas). We also thank V. Athanasoula for making double-checks of extracted data, ensuring that the current work meets the highest standards. S. Cortese, NIHR Research Professor (grant no. NIHR303122), is funded by the NIHR for this research project. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR, NHS or the UK Department of Health and Social Care. S. Cortese is also supported by NIHR grants NIHR203684, NIHR203035, NIHR130077, NIHR128472, RP-PG-0618-20003 and by grant 101095568-HORIZONHLTH-2022-DISEASE-07-03 from the European Research Executive Agency.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: C.J.G., L.B., A.C., S. Cortese, R.D. and M. Solmi. Screening and data extraction: C.J.G., L.B., L.J., M.N., G.P. and E.M. Data analysis: C.J.G. and J.R. Supervision and guidance: M. Sandbank, A.C., S. Cortese, R.D., M. Solmi, P.F.-P., K.K. and S. Caparos. Review and approval of final manuscript: all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

S. Cortese has declared reimbursement for travel and accommodation expenses from the Association for Child and Adolescent Central Health (ACAMH) in relation to lectures delivered for ACAMH, the Canadian AADHD Alliance Resource, the British Association of Psychopharmacology, Healthcare Convention and CCM Group team for educational activity on ADHD, and has received honoraria from Medice. M. Solmi received honoraria/has been a consultant for Angelini, AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim, Lundbeck and Otsuka. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Human Behaviour thanks John Harrington, Mahbub Hossain, David Mandell and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information sections 1–12.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gosling, C.J., Boisseleau, L., Solmi, M. et al. Complementary, alternative and integrative medicine for autism: an umbrella review and online platform. Nat Hum Behav 9, 2610–2619 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-025-02256-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-025-02256-9