Abstract

Deformation twinning, a phenomenon primarily documented within metallic systems, has remained essentially unexplored in covalent materials due to the formidable challenges posed by their inherent extreme hardness and brittleness. Here, by employing a five-degree-of-freedom nano-manipulation stage inside a transmission electron microscope, we reveal a loading-specific twinning criterion for cubic boron nitride and successfully activate extensive deformation twinning with substantial improvements in mechanical properties in <100>-oriented cubic boron nitride submicrometre pillars at room temperature. Beyond cubic boron nitride, this criterion is also proven widely applicable across a spectrum of covalent materials. Investigations on the twinning dynamics at the atomic level in cubic boron nitride suggest a continuous-transition-mediated pathway. These findings substantially advance our comprehension of twinning mechanisms in covalent face-centred cubic materials, and herald a promising avenue for microstructural engineering aimed at enhancing the strength and toughness of these materials in their applications.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data supporting this study’s findings are available within this Article and its Supplementary Information. Additional data are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

References

Christian, W. & Mahajant, S. Deformation twinning. Prog. Mater. Sci. 39, 1–157 (1995).

Venables, J. A. Deformation twinning in face-centred cubic metals. Philos. Mag. 6, 379–396 (1961).

Zhu, Y. T., Liao, X. Z. & Wu, X. L. Deformation twinning in nanocrystalline materials. Prog. Mater. Sci. 57, 1–62 (2012).

Rohatgi, A., Vecchio, K. S. & Gray, G. T. The influence of stacking fault energy on the mechanical behavior of Cu and Cu–Al alloys: deformation twinning, work hardening, and dynamic recovery. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 32, 135–145 (2001).

Lu, L., Shen, Y., Chen, X., Qian, L. & Lu, K. Ultrahigh strength and high electrical conductivity in copper. Science 304, 422–426 (2004).

Zhang, Z. et al. Dislocation mechanisms and 3D twin architectures generate exceptional strength-ductility-toughness combination in CrCoNi medium-entropy alloy. Nat. Commun. 8, 14390 (2017).

Oshima, Y., Nakamura, A. & Matsunaga, K. Extraordinary plasticity of an inorganic semiconductor in darkness. Science 360, 772–774 (2018).

Gludovatz, B. et al. A fracture-resistant high-entropy alloy for cryogenic applications. Science 345, 1153–1158 (2014).

Korte-Kerzel, S. Microcompression of brittle and anisotropic crystals: recent advances and current challenges in studying plasticity in hard materials. MRS Commun. 7, 109–120 (2017).

Ookawa, A. On the mechanism of deformation twin in fcc crystal. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn 12, 825–825 (1957).

Niewczas, M. & Saada, G. Twinning nucleation in Cu-8 at. % Al single crystals. Philos. Mag. A 82, 167–191 (2002).

Mahajan, S. & Chin, G. Y. Twin-slip, twin-twin and slip-twin interactions in Co-8 wt.% Fe alloy single crystals. Acta. Metall. 21, 173–179 (1973).

Thompson, N. Dislocation nodes in face-centred cubic lattices. Proc. Phys. Soc. B 66, 481–492 (1953).

Yamakov, V., Wolf, D., Phillpot, S. R., Mukherjee, A. K. & Gleiter, H. Dislocation processes in the deformation of nanocrystalline aluminium by molecular-dynamics simulation. Nat. Mater. 1, 45–49 (2002).

El-Danaf, E., Kalidindi, S. R. & Doherty, R. D. Influence of grain size and stacking-fault energy on deformation twinning in fcc metals. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 30, 1223–1233 (1999).

Wang, L. et al. New twinning route in face-centered cubic nanocrystalline metals. Nat. Commun. 8, 2142 (2017).

Siethojf, H. in Semiconductors and Semimetals Vol. 37 (eds Faber, K. T. & Malloy, K. J.) Ch. 3, 143–187 (Elsevier, 1992).

Li, X., Yin, S., Oh, S. H. & Gao, H. Hardening and toughening mechanisms in nanotwinned ceramics. Scr. Mater. 133, 105–112 (2017).

Nie, A. et al. Direct observation of room-temperature dislocation plasticity in diamond. Matter 2, 1222–1232 (2020).

Bu, Y., Wang, P., Nie, A. & Wang, H. Room-temperature plasticity in diamond. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 64, 32–36 (2021).

Brookes, C. The mechanical properties of cubic boron nitride. In Science of Hard Materials. Proceedings of the International Conference Vol. 20, 207–220 (International Atomic Energy Agency, 1986).

Tian, Y. et al. Ultrahard nanotwinned cubic boron nitride. Nature 493, 385–388 (2013).

Huang, Q. et al. Nanotwinned diamond with unprecedented hardness and stability. Nature 510, 250–253 (2014).

Vitek, V. Intrinsic stacking faults in body-centred cubic crystals. Philos. Mag. 18, 773–786 (1968).

Rice, J. R. Dislocation nucleation from a crack tip: an analysis based on the Peierls concept. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 40, 239–271 (1992).

Joós, B. & Duesbery, M. S. The Peierls stress of dislocations: an analytic formula. Phys. Rev. Lett. 78, 266–269 (1997).

Zhang, S. H., Legut, D. & Zhang, R. F. PNADIS: an automated Peierls–Nabarro analyzer for dislocation core structure and slip resistance. Comput. Phys. Commun. 240, 60–73 (2019).

Tadmor, E. B. & Bernstein, N. A first-principles measure for the twinnability of fcc metals. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 52, 2507–2519 (2004).

Bernstein, N. & Tadmor, E. B. Tight-binding calculations of stacking energies and twinnability in fcc metals. Phys. Rev. B 69, 094116 (2004).

Li, W. et al. First-principles prediction of the deformation modes in austenitic Fe-Cr-Ni alloys. Appl. Phys. Lett. 108, 081903 (2016).

Vel, L., Demazeau, G. & Etourneau, J. Cubic boron nitride: synthesis, physicochemical properties and applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 10, 149–164 (1991).

Zhang, Y., Bu, Y., Fang, X. & Wang, H. A compact design of four-degree-of-freedom transmission electron microscope holder for quasi-four-dimensional characterization. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 63, 1272–1279 (2020).

Zhang, Y. et al. Atomic-scale observation of the deformation and failure of diamonds by in situ double-tilt mechanical testing transmission electron microscope holder. Sci. China Mater. 63, 2335–2343 (2020).

Pajdla, T. & Matas, J. (eds) Computer Vision – ECCV 2004: 8th European Conference on Computer Vision, Prgue, Czech Republic, May 11-14, 2004. Proceedings, Part I (Springer, 2004).

Dougherty, L., Asmuth, J. C., Blom, A. S., Axel, L. & Kumar, R. Validation of an optical flow method for tag displacement estimation. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 18, 359–363 (1999).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phys. Rev. B 47, 558–561 (1993).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Hirth, J. P. & Lothe, J. Theory of Dislocations (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2017).

Zhang, R. F. et al. First-principles design of strong solids: approaches and applications. Phys. Rep. 826, 1–49 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52288102 to H.W., 52090022 to A.N., 12202379 to Y.B. and 92463305 to Z.Z.); the Natural Science Foundation of Hebei Province of China (E2024203054 to A.N. and E2022203109 to B.X.); the National Key R&D Program of China (2023YFB3712701 to Y.B.); and the National Science Foundation (EAR-1925920 to W.Y.). We acknowledge helpful discussions with X. Li at Tsinghua University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.N., H.W. and Y.T. initiated the project and created the experimental protocols. Y.B., J.H., P.L., C.W., T.J. and S.Z. carried out the fabrication of cBN nanopillars. Y.B., A.N. and H.W. conducted the in situ TEM testing. Z.S. and K.T. performed DFT calculations. A.N., Y.B., H.W., B.X., Z.Z., Z.L. and Y. W. analysed the data. Y.B., A.N., H.W., B.X., A.S., W.Y. and Y.T. wrote the paper and all the authors contributed to the discussion and revision of the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Materials thanks Kelvin Xie and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Dislocations in a <111>-oriented cBN pillar.

a, According to the inset selective area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern, slip plane was determined to be (010) plane. Four images were captured under various two-beam conditions: b, g = \([11\bar{3}]\), c, g = \([1\bar{3}1]\), around the [211] zone axis, d, g = \([1\bar{1}1]\) along the [110] zone axis and e, g = \([20\bar{2}]\) around the [010] zone axis. The dislocations exhibit clear contrast in b and e, but are extinct in c and d. According the g·b = 0 extinction criteria, the Burgers vector of the dislocations is 1/2 \([10\bar{1}]\), and the corresponding slip system is 1/2 \([10\bar{1}]\)(010). When the incident beam is parallel to the [010] direction [as shown in e], the viewing direction is nearly perpendicular to the (010) slip plane. We can approximately determine the geometric relationship between the dislocation line direction and the Burgers vector according to the TEM image. As shown in the inset of e, the dislocation half loops can be divided into two arm segments and one head segment (inset). The line direction of the arm segments is nearly parallel to the Burgers vector (yellow arrow), while the line direction of the head segment is nearly perpendicular to the Burgers vectors. Thus, these dislocation half loops are mixed type, including edge head segments and screw arm segments. f, The core structure of the edge head segment recorded by HAADF-STEM. Insets at the lower right corner of a-e are the corresponding SAED patterns.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Dislocations in a <110>-oriented cBN pillars.

a-c, A <110>-oriented nanopillar rotated around the <110> axis, showing dislocation morphologies at various viewed angles. According to the edge-on view of the dislocation slip plane and the inset SAED in b, the slip plane in this pillar is (001). To determining the type and Burgers vector of the dislocations, images were captured under various two-beam conditions. d, g = [040] around the [101] zone axis. e, g = \([11\bar{1}]\) around the [011] zone axis. f, g = [220] and g, g = \([2\bar{2}0]\) around the [001] zone axis. The dislocations are extinct in e and f, the Burgers vector is therefore b = 1/2 \([1\bar{1}0]\) based on the g·b = 0. According to the geometric relationship between Burgers vectors and the dislocation line direction in d, the head segments of the dislocations are edge type, and the arm segments are screw type. Insets at the upper right corner of d-g are the corresponding SAED patterns.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Along the strategy based on the loading-specific criterion, deformation twinning was activated in other brittle and hard covalent crystals with face-centered cubic structures.

a1-d1, The [010]-oriented single-crystalline diamond, silicon carbide (SiC), gallium arsenide (GaAs) and boron arsenide (BAs) pillars. a2-d2, The corresponding SAED patterns. a3-d3, Diamond, SiC, GaAs and BAs pillars after uniaxial compression. a4-d4, High-resolution TEM images revealing the generation of deformation twins.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Inverse pole figures illustrating the region where deformation twinning occurs across various loading orientations for a series of covalent crystals including diamond, cBN, SiC, BAs, and GaAs.

For each covalent material studied, the loading directions conducive to deformation twinning, considering activated leading and trailing partial dislocations on various slip planes relative to the initially activated leading partial dislocation, encompass a significantly broader region (left of the black line) compared to that predicted by our twinning criterion (left of the red line), which is based on the competition between partial dislocation slip on {111} and full dislocation slip on {100}. This finding underscores the robustness of our twinning criterion in accurately identifying the loading conditions that promote twinning.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Microstructural characterization of the indentation region on (100) surface.

a, Bright- and b, dark-field TEM images showing the high density of deformation twinning lamellas; c, Corresponding SAED pattern and d, high-resolution TEM image confirmed the extensive activation of deformation twinning in the single-crystal cBN post indentation, effectively ruling out any significant influence of potential gallium implantation during focused ion beam (FIB) milling on the mechanical behavior of cBN.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Viewing the deformation twinning at atomic scale using in-situ high-resolution TEM.

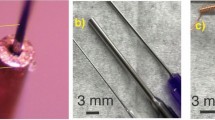

a, A <100>-oriented cBN nanopillar micromachined from the bulk counterpart using FIB and sequentially thinned to ~15 nm thick by low-energy argon plasma milling. b1 - b3, The generation process of a 14-atom-layer twin during compression. b4, A secondary twin generated on the further compression.

Extended Data Fig. 7 A partial dislocation gliding left a trail of stacking fault.

a, The cBN lattice before generating partial dislocation and stacking fault. b, A partial dislocation with Burgers vector of 1/6 <112> and the trailing stacking fault were produced by nano-compression. c, The stacking fault propagated with the partial dislocation gliding.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Post-deformation STEM characterization of twin structures in the indented cBN region.

a, BF-STEM image providing an overview of the twin lamellas; b, Atomic-resolution HAADF-STEM image revealing the atomic arrangement within the transition-state lattice.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Continuous-transition-mediated deformation twinning in diamond.

a, A top view image of a deformed <100> -oriented diamond anvil tip after diamond anvil cell test under pressure of ~360 GPa. b, The dark field TEM image shows that there generated high density of twins in the deformed diamond anvil tip. c, The corresponding SAED patterns. d, HAADF-STEM image captures the transition layer in front of the twin boundary, indicating that continuous-transition-mediated deformation twinning occurs in this bulk diamond.

Extended Data Fig. 10 Assessment of Ga implantation in cBN nanopillars post FIB milling and argon cleaning.

a, EDS mapping. b, EELS mapping. c1, APT three-dimensional reconstruction of a cBN nanopillar. Note the Ga map displays only background noise. c2, Corresponding mass spectrum from the entire APT volume, where the Ga mass-to-charge ratio peak is not detected. All analytic techniques consistently demonstrated minimal Ga content in the cBN nanopillars post-cleaning, with levels below the instrument’s noise threshold.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Text 1, Table 1, Figs. 1–11, captions for Videos 1–9 and references.

Supplementary Video 1

This typical video records the deformation process of a cBN pillar with <100> orientation. The video speed is two times the speed of the experiment.

Supplementary Video 2

An additional example showing the deformation twinning in a <100>-oriented cBN pillar during uniaxial compression.

Supplementary Video 3

In situ TEM compression on a <111>-oriented cBN pillar. The video speed is two times the speed of the experiment.

Supplementary Video 4

In situ TEM compression on a <100>-oriented cBN pillar. The video speed is two times the speed of the experiment.

Supplementary Video 5

In situ atomic-resolution characterization of the deformation twinning process in cBN. The video speed is two times the speed of the experiment.

Supplementary Video 6

Abundant partial dislocation behaviours in <100>-oriented cBN nanopillar during compression.

Supplementary Video 7

Continuous-transition-mediated twinning mechanism in cBN.

Supplementary Video 8

Continuous-transition-mediated twin thickening in cBN.

Supplementary Video 9

The five-degree-of-freedom nano-manipulation of the X-Nano double-tilt TEM holder.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Bu, Y., Su, Z., Huang, J. et al. Activating deformation twinning in cubic boron nitride. Nat. Mater. 24, 361–368 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-024-02111-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-024-02111-8

This article is cited by

-

Outstanding issues and emerging frontiers in fracture mechanics

International Journal of Fracture (2026)

-

Ceramic crystals stretch like metal

Nature Nanotechnology (2025)

-

Solids in nano-scales: extreme strength and elasticity

Acta Mechanica Sinica (2025)