Abstract

Elastic seals safeguard stretchable electronics from reactive species in the surrounding environment. However, elastic contact with device modules and the intrinsic small-molecule permeability of elastomers limit the hermeticity of devices. Here we present a viscoplastic surface effect in polymeric elastomers for deriving sealing platforms with high hermeticity and large stretchability, made possible by controlling phase separations of partially miscible polar plastics within the near-surface region of block copolymer elastomers. The resulting viscoplastic surface allows the elastomer to form defect-free interfaces regardless of their size, materials chemistry and geometry. This capability facilitates the airtight integration of device modules to mitigate side leakage and enable the seamless assembly of high-potential gas barriers to prevent bulk penetration. A multilayer seal that incorporates scavenging components demonstrates properties that are as hermetic as aluminium foil while being stretchable like a rubber band. This breakthrough extends the operational lifetime of perovskite optoelectronics, hydrogel thermoelectrics and implantable bioelectronics without sacrificing their stretchability or efficiency.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All data are available in the main text or the Supplementary Information. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Zhong, D. et al. High-speed and large-scale intrinsically stretchable integrated circuits. Nature 627, 313–320 (2024).

Madhvapathy, S. R. et al. Implantable bioelectronic systems for early detection of kidney transplant rejection. Science 381, 1105–1112 (2023).

Mackanic, D. G., Chang, T.-H., Huang, Z., Cui, Y. & Bao, Z. Stretchable electrochemical energy storage devices. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 4466–4495 (2020).

Fukuda, K. et al. A bending test protocol for characterizing the mechanical performance of flexible photovoltaics. Nat. Energy 9, 1335–1343 (2024).

Zhang, Z. et al. High-brightness all-polymer stretchable LED with charge-trapping dilution. Nature 603, 624–630 (2022).

Nguyen, T. N., Iranpour, B., Cheng, E. & Madden, J. D. W. Washable and stretchable Zn–MnO2 rechargeable cell. Adv. Energy Mater. 12, 2103148 (2022).

Zheng, Y. et al. Environmentally stable and stretchable polymer electronics enabled by surface-tethered nanostructured molecular-level protection. Nat. Nanotechnol. 18, 1175–1184 (2023).

Xu, J. et al. Highly stretchable polymer semiconductor films through the nanoconfinement effect. Science 355, 59–64 (2017).

Sang, M., Kim, K., Shin, J. & Yu, K. J. Ultra-thin flexible encapsulating materials for soft bio-integrated electronics. Adv. Sci. 9, 2202980 (2022).

Mariello, M., Kim, K., Wu, K., Lacour, S. P. & Leterrier, Y. Recent advances in encapsulation of flexible bioelectronic implants: materials, technologies, and characterization methods. Adv. Mater. 34, 2201129 (2022).

Faiz, S., Kim, H. W., Oh, J., Veerapandian, S. & Jeong, U. High-precision stretchable ionic temperature sensor passivated with a liquid metal/block copolymer multilayer film. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 28825–28832 (2023).

Shen, Q. et al. Liquid metal-based soft, hermetic, and wireless-communicable seals for stretchable systems. Science 379, 488–493 (2023).

Song, E., Li, J., Won, S. M., Bai, W. & Rogers, J. A. Materials for flexible bioelectronic systems as chronic neural interfaces. Nat. Mater. 19, 590–603 (2020).

Li, K. et al. A generic soft encapsulation strategy for stretchable electronics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1806630 (2019).

Shao, Y. et al. A universal packaging substrate for mechanically stable assembly of stretchable electronics. Nat. Commun. 15, 6106 (2024).

Li, N. et al. Bioadhesive polymer semiconductors and transistors for intimate biointerfaces. Science 381, 686–693 (2023).

Ji, S. & Chen, X. Enhancing the interfacial binding strength between modular stretchable electronic components. Natl Sci. Rev. 10, nwac172 (2023).

Veerapandian, S. et al. Hydrogen-doped viscoplastic liquid metal microparticles for stretchable printed metal lines. Nat. Mater. 20, 533–540 (2021).

Liu, Y. et al. Morphing electronics enable neuromodulation in growing tissue. Nat. Biotechnol. 38, 1031–1036 (2020).

Lee, S. et al. A shape-morphing cortex-adhesive sensor for closed-loop transcranial ultrasound neurostimulation. Nat. Electron. 7, 800–814 (2024).

Takalloo, S. E. et al. Impermeable and compliant: SIBS as a promising encapsulant for ionically electroactive devices. Robotics 8, 60 (2019).

Szabó, P., Epacher, E., Földes, E. & Pukánszky, B. Miscibility, structure and properties of PP/PIB blends. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 383, 307–315 (2004).

Yang, S., Zhang, Y.-W. & Zeng, K. Analysis of nanoindentation creep for polymeric materials. J. Appl. Phys. 95, 3655–3666 (2004).

Tang, B. & Ngan, A. H. W. Accurate measurement of tip–sample contact size during nanoindentation of viscoelastic materials. J. Mater. Res. 18, 1141–1148 (2003).

Wiersma, J. & Sain, T. A coupled viscoplastic-damage constitutive model for semicrystalline polymers. Mech. Mater. 176, 104527 (2023).

Venkatesh, R. B. & Lee, D. Conflicting effects of extreme nanoconfinement on the translational and segmental motion of entangled polymers. Macromolecules 55, 4492–4501 (2022).

Liang, C. et al. Stiff and self-healing hydrogels by polymer entanglements in co-planar nanoconfinement. Nat. Mater. 24, 599–606 (2025).

Wang, Z. Y., et al. Ion transport in 2D nanostructured π-conjugated thieno[3,2-b]thiophene-based liquid crystal. ACS Nano 16, 20714–20729 (2022).

Wang, Y., Hasegawa, T., Matsumoto, H. & Michinobu, T. Significant improvement of unipolar n-type transistor performances by manipulating the coplanar backbone conformation of electron-deficient polymers via hydrogen bonding. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 3566–3575 (2019).

López-Barrón, C. R., Zhou, H., Younker, J. M. & Mann, J. A. Molecular structure, chain dimensions, and linear rheology of poly(4-vinylbiphenyl). Macromolecules 50, 9048–9057 (2017).

Mitchell, G. R. & Windle, A. H. Structure of polystyrene glasses. Polymer 25, 906–920 (1984).

Lim, D.-H. et al. Structural insight into aggregation and orientation of TPD-based conjugated polymers for efficient charge-transporting properties. Chem. Mater. 31, 4629–4638 (2019).

Tang, L., Watts, B., Thomsen, L. & McNeill, C. R. Morphology and charge transport properties of P(NDI2OD-T2)/polystyrene blends. Macromolecules 54, 11134–11146 (2021).

Zhou, J. & Komvopoulos, K. Surface and interface viscoelastic behaviors of thin polymer films investigated by nanoindentation. J. Appl. Phys. 100, 114329 (2006).

Qiu, H. N. et al. Stress relaxation and creep response of glassy hydrogels with dense physical associations. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 17, 9981–9991 (2025).

Hao, Z. et al. Mobility gradients yield rubbery surfaces on top of polymer glasses. Nature 596, 372–376 (2021).

Kim, S. Y., Park, M. J., Balsara, N. P. & Jackson, A. Confinement effects on watery domains in hydrated block copolymer electrolyte membranes. Macromolecules 43, 8128–8135 (2010).

Shi, B. et al. Short hydrogen-bond network confined on COF surfaces enables ultrahigh proton conductivity. Nat. Commun. 13, 6666 (2022).

Paetzold, R., Winnacker, A., Henseler, D., Cesari, V. & Heuser, K. Permeation rate measurements by electrical analysis of calcium corrosion. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 74, 5147–5150 (2003).

Keller, P. E. & Kouzes, R. T. Water Vapor Permeation in Plastics Technical Report PNNL-26070 (US Department of Energy, 2017); https://doi.org/10.2172/1411940.

Carcia, P. F., McLean, R. S., Groner, M. D., Dameron, A. A. & George, S. M. Gas diffusion ultrabarriers on polymer substrates using Al2O3 atomic layer deposition and SiN plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition. J. Appl. Phys. 106, 023533 (2009).

Ochirkhuyag, N. et al. Stretchable gas barrier films using liquid metal toward a highly deformable battery. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 48123–48132 (2022).

Kempe, M. D., Dameron, A. A. & Reese, M. O. Evaluation of moisture ingress from the perimeter of photovoltaic modules. Prog. Photovolt. 22, 1159–1171 (2014).

Apeagyei, A. K., Grenfell, J. R. A. & Airey, G. D. Application of Fickian and non-Fickian diffusion models to study moisture diffusion in asphalt mastics. Mater. Struct. 48, 1461–1474 (2015).

Carter, H. G. & Kibler, K. G. Langmuir-type model for anomalous moisture diffusion in composite resins. J. Compos. Mater. 12, 118–131 (1978).

Zhou, H. et al. Water passivation of perovskite nanocrystals enables air-stable intrinsically stretchable color-conversion layers for stretchable displays. Adv. Mater. 32, 2001989 (2020).

Pinchuk, L. The development of a SIBS shunt to treat glaucoma. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 39, 530–540 (2023).

Gan, T. et al. Conformally adhesive, large-area, solid-like, yet transient liquid metal thin films and patterns via gelatin-regulated droplet deposition and sintering. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 42744–42756 (2022).

Iqbal, H. F. et al. Suppressing bias stress degradation in high performance solution processed organic transistors operating in air. Nat. Commun. 12, 2352 (2021).

Acknowledgements

Y.Y. was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52272299), the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province, China (No. 2024A1515012366), the Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Sustainable Biomimetic Materials and Green Energy (2024B1212010003), the High Level of Special Funds (G03050K002) and the Shenzhen Science and Technology Innovation Commission (KQTD20180411143514543). W.L. was supported by the NSFC program for Distinguished Young Scholars (T2425012), the Shenzhen Innovation Program for Distinguished Young Scholars (RCJC20210706091949018) and the Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory Program from the Department of Science and Technology of Guangdong Province (2021B1212040001). Y.S. was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52303107) and the Research Projects of Yancheng Institute of Technology (No. xjr2023029). All calculations were carried out on the Taiyi cluster supported by the Center for Computational Science and Engineering of Southern University of Science and Technology. We thank the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility for providing GIWAXS (31124.02.SSRF.BL14B1) and SAXS (31124.02.SSRF.BL16B1) measurements, and Guangzhou Herun Instrument Technology Co., Ltd. for facilitating the OTR measurements. We thank S. Xu at the Cryo-EM Center of Southern University of Science and Technology for providing technical support during TEM characterization.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.X. and Y.Y. conceived the idea and designed the experiments. R.X., C.L. and Y.S. performed the material synthesis, structural characterization, property measurements and device sealing of SVS, scavenging SVS and blocking SVS. D.H. and Z.H. fabricated and measured the PSC and helped with the GIWAXS characterization experiments. J.Y., K.C. and F.R. conducted the nanoindentation measurements in SEM and performed the device implantation experiments. M.Y. and W.L. fabricated and measured the thermoelectric cell. H.Y. and G.L. carried out the MD simulations of water diffusion. D.C., G.C. and Y.D. provided assistance with the material synthesis and characterization. R.X., C.L., Y.S. and Y.Y. wrote the paper with comments from all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Materials thanks Jiheong Kang and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Schematic and calculation of water diffusion in SIBS and SEBS.

a, Molecular structures of SIBS and SEBS. b, Schematic illustration of water transport through the SIBS networks (dwelling and back-and-forth states). These two states are governed by the thermal vibrations of the methyl side chains of the PIB segments. When the thermal fluctuation ‘closes’ the methyl groups (gate-off), water molecules dwell in the free-volume cavity. Conversely, when the thermal fluctuation ‘opens’ the methyl groups (gate-on), water molecules start to jump back and forth between two neighboring free-volume cavities. c, MD simulations illustrate the transport of water molecules in PIB segments within the SIBS network over time, corresponding to the dwelling and back-and-forth states illustrated in (b). d, MD simulations of water molecule displacements at the interface of PS/PIB blocks (SIBS) and PS/PEB blocks (SEBS) as a function of time, showing slower diffusion in SIBS compared with SEBS. e, f, 3D simulation results of SEBS (e) and SIBS (f) refer to the findings in (d), further confirming a back-and-forth diffusion mode for water molecules in SIBS.

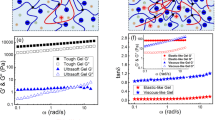

Extended Data Fig. 2 Nanoindentation tests of SIBS and SVS.

a, b, SEM images of SVS (a) and SIBS (b) during in-situ nanoindentation tests (i) the tip approaching the surface; (ii) the tip compressing the film; (iii) the tip withdrawing from the film. The polymer residue on the tip was a result of the viscous property of the SVS surface (a-iii). The fractured concave (a-iii) shows the plastic property of the SVS film. c, Load-depth curve of the nanoindentation test on the top surface of SVS, showing an elastic deformation behavior similar to that of the SIBS. This result verifies that the viscoplastic surface effect only occurs on the bottom surface of SVS (the side adjacent to the glass substrate during solidification). d, Nanoindentation force-relaxation test on SIBS and SVS surfaces, showing higher surface mobility of SVS.

Extended Data Fig. 3 SVS fabrication through control of phase separation.

a, A scheme depicting the fabrication process of SVS. b, Cross-sectional SEM images of SVS samples show a gradual increase in the gradient degree of MAPP domains with the increase of the holding time. Insets present the corresponding confocal fluorescence images. To enhance the visibility of the MAPP phase, the concentration of MAPP components was increased to 5 wt% for this characterization. The gradient distribution of the MAPP phase in the SIBS network can be adjusted by regulating the holding time of the mixing solution during the second step shown in (a). When holding time was short, MAPP condensates did not coalesce, leading to the formation of numerous MAPP nanodomains within the SIBS network. With the prolongation of the holding time, MAPP gradually aggregated and settled towards the bottom of the substrate, creating a micro/nano-confined space between the substrate and the MAPP domains. Upon the evaporation of the solvent, these MAPP domains were locked in a phase-separation state with PP chains entangled with PIB segments in SIBS. Extending the holding time to 24 hours caused a complete separation of MAPP from the SIBS matrix, resulting in defective interfaces between the MAPP domain and the SIBS matrix. c, Schematics of the homogenous SIBS/MAPP, SVS, and layer-like SIBS/MAPP films.

Extended Data Fig. 4 AFM phase images of the SVS film.

a, SVS surface that was distant from the MAPP domain, that is, equivalent to the pristine SIBS surface. b, SVS surface that was adjacent to the MAPP domain. The diameter of PS was smaller than that of the pristine SIBS case. c, SVS surface that was in between MAPP domains. The statistical PS size distribution becomes broader.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Structural characterization of the molecular configuration and free volume in SIBS and SVS.

a, Two-dimensional (2D) GIWAXS patterns of SIBS and SVS within the surface region. b, Corresponding 1D GIWAXS profiles extracted from the 2D GIWAXS data. The shoulders observed at the wider angle, at q4, arise from the aromatic π−π interactions between two adjacent phenyl groups that are attached to the backbone. Compared to the SIBS, the peak positions for q1 and q3 disappear in SVS, while the intensity of q2 is enhanced and that of q4 is reduced, indicating a weakening of π−π stacking interactions within the rearranged PS nanodomains. c, Positron annihilation lifetime spectra measured in SIBS and SVS. d, The deconvoluted intensities and lifetimes from the spectra in (c). The calculated fractional free volume (FFV) was identical for SIBS and SVS, suggesting no defects were created after the introduction of MAPP.

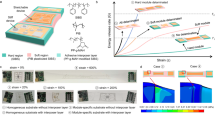

Extended Data Fig. 6 Schematics for the fabrication process of the Scavenging SVS.

(1) A hollowed-out mask was attached to the bottom of the SVS to cover its four edges. (2) Molecular sieve particles were spread onto the exposed central region. (3) The particles were then compressed to embed them into the SVS. (4) The mask was removed. (5) A glycerol/Ectoin droplet was placed in the center. (6) Another SVS film—with molecular sieves embedded in its central region—was used to sandwich the glycerol/Ectoin droplet, and a slender exhaust tube was positioned along the edge of the SVS to facilitate air exhaustion. (7) During the sandwiching process, air was slowly exhausted by gently pressing the edges of the two SVS films with fingers. (8) The exhaust tube was removed, and the remaining region was sealed via hot pressing.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Characterization of molecular sieves (MS) embedded in SIBS and SVS.

a, Top-view SEM images of the SIBS surface embedded with 3A-type MS. b, SEM images after the sample in (a) has undergone 10,000 cycles of 100% stretch. c, d, SEM images of SIBS film embedded with MS particles during the stretch (c) and after recovery (d). Detachment of MS particles was observed in SIBS. e, f, Top-view and side-view SEM images of SVS embedded with 3A-type MS. g, h, SEM images of the SVS film with MS particles after undergoing 10,000 cycles of 100% stretch, showing no delamination. The inset image in (h) reveals that the MS particles were intimately covered by a thin skin layer, confirming the conformal adhesion due to the viscoplastic surface of SVS. i, Photographs of Scavenging SIBS and Scavenging SVS. The liquid layer was dyed for improved visibility. (i) Before pressing; (ii) After pressing with finger for 3 seconds; (iii) After 3 minutes of recovery from pressing.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Schematics for the fabrication process of the Blocking SVS.

(1) A hollowed-out mask was placed on the plasma-treated SVS film to shield its four edges. (2) A mixture of E-GaIn liquid metal (LM) and gelatin solution was poured into the central region and solidified at 4 °C. (3) The sample was immersed in a glycerol solution for solvent exchange. (4) After soaking, a tough gelatin-based organogel was peeled off from the SVS surface, leaving a metallic gel layer. (5) An E-GaIn droplet was placed in the central area. (6) The droplet spontaneously wetted the surface. (7) An identical SVS/gelatin/LM film was used to sandwich the LM interlayer. (8) The remaining edges were sealed by gently pressing the two SVS films together.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Structure and properties of Scavenging-Blocking SVS.

a, Fluorescence optical microscope image for the Scavenging SVS and SEM image for the Blocking SVS that were used for fabricating the Scavenging-Blocking SVS. b, c, Photographs (b) and WVTR at 25 °C and 90% RH (c) for the 180 μm-thick Scavenging-Blocking SVS under 50% stretch. The Scavenging-Blocking SVS can endure large-degree biaxial stretch and poke, demonstrating its high mechanical stability.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Discussions, Methods, Figs. 1–34, Tables 1–3 and Refs. 1–35.

Supplementary Video 1

In situ indentation test of SVS.

Supplementary Video 2

In situ indentation test of SIBS.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data for Fig. 1d,e.

Source Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data for Fig. 2b.

Source Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data for Fig. 3b,e–h.

Source Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data for Fig. 4b,d,e,g,h.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data for Extended Data Fig. 1c,d.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data for Extended Data Fig. 2c,d.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data for Extended Data Fig. 4a–c.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 5

Statistical source data for Extended Data Fig. 5b–d.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 9

Statistical source data for Extended Data Fig. 9c.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Xia, R., Li, C., Shao, Y. et al. Hermetic stretchable seals enabled by a viscoplastic surface effect. Nat. Mater. 24, 2011–2018 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-025-02386-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-025-02386-5

This article is cited by

-

Sealing stretchable electronics through a viscoplastic surface effect

Nature Materials (2025)