Abstract

DNA degradation (Dnd) is a widespread bacterial antiphage defence system that relies on DNA phosphorothioate (PT) modification for self/non-self discrimination and subsequent degradation of unmodified DNA. Phages employ counterstrategies to evade host immunity, but anti-Dnd immunity has not been characterized. Here we report an immune evasion protein encoded by the Salmonella phage JSS1 that contributes to subverting Dnd and other defence systems. Using quantitative proteomic and phosphoproteomic analyses, we show that the protein JSS1_004 employs N-terminal Ser/Thr/Tyr protein kinase activity to catalyse the multisite phosphorylation of host DndFGH. Notably, JSS1_004 also phosphorylates other bacterial immune systems to varying degrees, including CRISPR‒Cas, QatABCD, SIR2+HerA and DUF4297+HerA. Given that JSS1_004 and its homologues are widespread in phylogenetically diverse phages, we suggest that this strategy constitutes a family of immune evasion proteins that increases the chances of phage proliferation even when a host deploys multiple defence systems.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The complete genome of the S. enterica phage JSS1 has been deposited in GenBank under accession number OP185508. The proteomic and phosphoproteomic data of phage-infected S. enterica have been deposited in PRIDE under the accession numbers PXD056211 and PXD056217, respectively, and those of phage-infected CX1(pWHU4390) have been deposited in the PRIDE under the accession numbers PXD056223 and PXD056225, respectively. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Wang, Y., Fan, H. & Tong, Y. Unveil the secret of the bacteria and phage arms race. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 4363 (2023).

Wilson, G. G. & Murray, N. E. Restriction and modification systems. Annu. Rev. Genet. 25, 585–627 (1991).

Loenen, W. A., Dryden, D. T., Raleigh, E. A., Wilson, G. G. & Murray, N. E. Highlights of the DNA cutters: a short history of the restriction enzymes. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 3–19 (2014).

Lopatina, A., Tal, N. & Sorek, R. Abortive infection: bacterial suicide as an antiviral immune strategy. Annu. Rev. Virol. 7, 371–384 (2020).

Barrangou, R. et al. CRISPR provides acquired resistance against viruses in prokaryotes. Science 315, 1709–1712 (2007).

Gao, H. et al. Nicking mechanism underlying the DNA phosphorothioate-sensing antiphage defense by SspE. Nat. Commun. 13, 6773 (2022).

Kuzmenko, A. et al. DNA targeting and interference by a bacterial Argonaute nuclease. Nature 587, 632–637 (2020).

Zeng, Z. et al. A short prokaryotic Argonaute activates membrane effector to confer antiviral defense. Cell Host Microbe 30, 930–943.e6 (2022).

Goldfarb, T. et al. BREX is a novel phage resistance system widespread in microbial genomes. EMBO J. 34, 169–183 (2015).

Cohen, D. et al. Cyclic GMP–AMP signalling protects bacteria against viral infection. Nature 574, 691–695 (2019).

Tal, N. et al. Cyclic CMP and cyclic UMP mediate bacterial immunity against phages. Cell 184, 5728–5739.e16 (2021).

Xiong, X. et al. SspABCD-SspE is a phosphorothioation-sensing bacterial defence system with broad anti-phage activities. Nat. Microbiol. 5, 917–928 (2020).

Jiang, S. et al. A DNA phosphorothioation-based Dnd defense system provides resistance against various phages and is compatible with the Ssp defense system. mBio 14, e0093323 (2023).

Gao, L. et al. Diverse enzymatic activities mediate antiviral immunity in prokaryotes. Science 369, 1077–1084 (2020).

Xiong, L. et al. A new type of DNA phosphorothioation-based antiviral system in archaea. Nat. Commun. 10, 1688 (2019).

Zou, X. et al. Systematic strategies for developing phage resistant Escherichia coli strains. Nat. Commun. 13, 4491 (2022).

Wang, L. et al. Phosphorothioation of DNA in bacteria by dnd genes. Nat. Chem. Biol. 3, 709–710 (2007).

Wu, D. et al. The functional coupling between restriction and DNA phosphorothioate modification systems underlying the DndFGH restriction complex. Nat. Catal. 5, 1131–1144 (2022).

Tong, T. et al. Occurrence, evolution, and functions of DNA phosphorothioate epigenetics in bacteria. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, E2988–E2996 (2018).

Chen, C. et al. Convergence of DNA methylation and phosphorothioation epigenetics in bacterial genomes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 4501–4506 (2017).

Wu, X. et al. Epigenetic competition reveals density-dependent regulation and target site plasticity of phosphorothioate epigenetics in bacteria. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 14322–14330 (2020).

Cao, B. et al. Genomic mapping of phosphorothioates reveals partial modification of short consensus sequences. Nat. Commun. 5, 3951 (2014).

Wei, Y. et al. Single-molecule optical mapping of the distribution of DNA phosphorothioate epigenetics. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, 3672–3680 (2021).

Studier, F. W. & Movva, N. R. SAMase gene of bacteriophage T3 is responsible for overcoming host restriction. J. Virol. 19, 136–145 (1976).

Yirmiya, E. et al. Phages overcome bacterial immunity via diverse anti-defence proteins. Nature 625, 352–359 (2024).

Pinilla-Redondo, R. et al. Discovery of multiple anti-CRISPRs highlights anti-defense gene clustering in mobile genetic elements. Nat. Commun. 11, 5652 (2020).

Hwang, S. & Maxwell, K. L. Meet the anti-CRISPRs: widespread protein inhibitors of CRISPR-Cas systems. CRISPR J. 2, 23–30 (2019).

Bhoobalan-Chitty, Y., Johansen, T. B., Di Cianni, N. & Peng, X. Inhibition of Type III CRISPR-Cas immunity by an archaeal virus-encoded anti-CRISPR protein. Cell 179, 448–458.e11 (2019).

Hobbs, S. J. et al. Phage anti-CBASS and anti-Pycsar nucleases subvert bacterial immunity. Nature 605, 522–526 (2022).

Garb, J. et al. Multiple phage resistance systems inhibit infection via SIR2-dependent NAD+ depletion. Nat. Microbiol. 7, 1849–1856 (2022).

Wang, L., Jiang, S., Deng, Z., Dedon, P. C. & Chen, S. DNA phosphorothioate modification—a new multi-functional epigenetic system in bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 43, 109–122 (2019).

Atanasiu, C., Su, T. J., Sturrock, S. S. & Dryden, D. T. Interaction of the ocr gene 0.3 protein of bacteriophage T7 with EcoKI restriction/modification enzyme. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 3936–3944 (2002).

Isaev, A. et al. Phage T7 DNA mimic protein Ocr is a potent inhibitor of BREX defence. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, 5397–5406 (2020).

Tabib-Salazar, A. et al. T7 phage factor required for managing RpoS in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, E5353–E5362 (2018).

Brunovskis, I. & Summers, W. C. The process of infection with coliphage T7. V. Shutoff of host RNA synthesis by an early phage function. Virology 45, 224–231 (1971).

Michalewicz, J. & Nicholson, A. W. Molecular cloning and expression of the bacteriophage T7 0.7 (protein kinase) gene. Virology 186, 452–462 (1992).

Rahmsdorf, H. J. et al. Protein kinase induction in Escherichia coli by bacteriophage T7. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 71, 586–589 (1974).

Gone, S. & Nicholson, A. W. Bacteriophage T7 protein kinase: site of inhibitory autophosphorylation, and use of dephosphorylated enzyme for efficient modification of protein in vitro. Protein Expr. Purif. 85, 218–223 (2012).

Hirsch-Kauffmann, M., Herrlich, P., Ponta, H. & Schweiger, M. Helper function of T7 protein kinase in virus propagation. Nature 255, 508–510 (1975).

Qimron, U., Tabor, S. & Richardson, C. C. New details about bacteriophage T7-host interactions: researchers are showing renewed interest in learning how phages interact with bacterial hosts, adapting to and overcoming their defenses. Microbe Mag. 5, 117–122 (2010).

Marchand, I., Nicholson, A. W. & Dreyfus, M. High-level autoenhanced expression of a single-copy gene in Escherichia coli: overproduction of bacteriophage T7 protein kinase directed by T7 late genetic elements. Gene 262, 231–238 (2001).

Wang, W. et al. Stromal induction of BRD4 phosphorylation results in chromatin remodeling and BET inhibitor resistance in colorectal cancer. Nat. Commun. 12, 4441 (2021).

Dissmeyer, N. & Schnittger, A. Use of phospho-site substitutions to analyze the biological relevance of phosphorylation events in regulatory networks. Methods Mol. Biol. 779, 93–138 (2011).

Stateva, S. R. et al. Characterization of phospho-(tyrosine)-mimetic calmodulin mutants. PLoS ONE 10, e0120798 (2015).

Brüssow, H. & Hendrix, R. W. Phage genomics: small is beautiful. Cell 108, 13–16 (2002).

Suttle, C. A. Marine viruses—major players in the global ecosystem. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5, 801–812 (2007).

Yan, N. & Chen, Z. J. Intrinsic antiviral immunity. Nat. Immunol. 13, 214–222 (2012).

Zhang, X. et al. The serine/threonine/tyrosine kinase STY46 defends against hordeivirus infection by phosphorylating γb protein. Plant Physiol. 186, 715–730 (2021).

Depardieu, F. et al. A eukaryotic-like serine/threonine kinase protects Staphylococci against phages. Cell Host Microbe 20, 471–481 (2016).

Doron, S. et al. Systematic discovery of antiphage defense systems in the microbial pangenome. Science 359, eaar4120 (2018).

Brettin, T. et al. RASTtk: a modular and extensible implementation of the RAST algorithm for building custom annotation pipelines and annotating batches of genomes. Sci. Rep. 5, 8365 (2015).

Price, M. N., Dehal, P. S. & Arkin, A. P. FastTree: computing large minimum evolution trees with profiles instead of a distance matrix. Mol. Biol. Evol. 26, 1641–1650 (2009).

Capella-Gutiérrez, S., Silla-Martínez, J. M. & Gabaldón, T. trimAl: a tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics 25, 1972–1973 (2009).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31925002 to S.C., 32125001 to L.W. and 32361133560 to C.C.), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFA0912500 to S.C.), the Wuhan Science and Technology Major Project (2023020302020708 to L.W.), the Shenzhen Key Laboratory of Microbiology in Genomic Modification and Editing and Application (Shenzhen Science and Technology Program, ZDSYS20230626090759006 to S.C.), the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2023A1515110845 to S.J.) and the Shenzhen Portion of Shenzhen-Hong Kong Science and Technology Innovation Cooperation Zone (project number HTHZQSWS-KCCYB-2023060 to S.C.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.C., L.W., C.C. and S.J. designed the research project. S.J., C.C., W.H., Y.H., X.D., Y.W., H.O. and C.X. performed the experiments. L.W., S.J., C.C., W.H., Y.H., X.D., Y.W., H.O., L.J., Z.D. C.X. and S.C. contributed to data analysis. L.W., S.J., C.C. and S.C. wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Authors L.W., S.C., C.C. and S.J. have filed a Chinese patent application (202410735378X) on the basis of the findings in the paper. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Microbiology thanks Chase Beisel, Konstantin Severinov and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Characterization of phage JSS1 and its mutants.

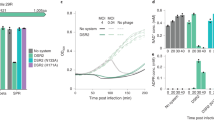

(a) Transmission electron microscopy image of phage JSS1. Phage JSS1 contains an icosahedral head that is approximately 60 nm in diameter and links with a stubby and noncontractile tail. (b) Verification of JSS1_004 deletion. PCR and DNA sequencing analyses were conducted to verify the deletion of JSS1_004 in the phage genome using primer pair 5′-TGAAGAAAGGCTACAGGTCTA-3′ and 5′-CTTCGTGTTCTAACTCAAGCT-3′. (c) One-step growth curve of JSS1 and JSS1Δ004. Data represent the mean ± SD from three independent experiments. (d) Burst size of JSS1 and JSS1Δ004 in XTG103. Data represent the mean ± SD from three independent experiments. NS, not significant. (e) Phage plaque assays on Cerro 87 or XTG103 using 5 μL of each serial tenfold dilution of phage JSS1 and its derivatives.

Extended Data Fig. 2 COG analysis of the phosphorylated proteins identified in JSS1-infected Cerro 87 cells.

Similar to the effect of Gp0.7 during T7 invasion, the β’ subunit of RNAP (category K) and the translation initiation factors IF2 and IF3 (category J) were phosphorylated in JSS1-infected Cerro 87 cells.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Phage plaque assays of S. enterica and its mutant strains.

Phage plaque assays on S. enterica strains expressing wild-type DndFGH and a set of variants with nonphosphorylatable (T-to-A, S-to-A and Y-to-F) or phosphomimetic mutations (T/Y/S-to-D and T/Y/S-to-E) with phages JSS1 or JSS1Δ004, respectively.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Effect of nonphosphorylatable mutations (T-to-A and Y-to-F) or mimic phosphorylation (T/Y-to-E) on DndFGH complex assembly determined by a pull-down assay.

N-terminal 6 × His-tag-labeled DndH/DndHY1510F/DndHY1510E was used as bait to pull down purified DndF, DndG and their derivatives. Individual DndF, DndG and derivatives were fused with maltose-binding protein (MBP), and the resultant fusion protein expression was driven by the IPTG-inducible PT7 promoter. Purified MBP fusion proteins were treated with TEV protease before the pull-down assay was performed. The input and pull-down elution samples were resolved by 10% SDS‒PAGE.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Multiple phosphorylation events of DndFGH did not influence protein expression or complex formation.

(a) The plasmid, carrying dndFGH under a native promoter with a FLAG-tag to the N-terminus of DndF/DndFT22A/T23A-Y-E and a 6 × His-tag to the C-terminus of DndH/DndHY1510F-S/T/Y-E, was introduced into CX1. The expression levels of DndF, DndH and their derivatives were determined by Western blotting. RpoB was used as an internal control. The results are representative of three independent experiments. (b) The expression levels of DndF, DndH and their derivatives were measured and normalized to RopB as the mean ± SD. NS, not significant. (c) C-terminal 6 × His-tag-labeled DndH/ DndHY1510F-S/T/Y-E was used as bait to pull down DndF, DndG and their derivatives. The input and pull-down elution samples were resolved by 10% SDS‒PAGE. DndFT22A/T23A-Y-EGHY1510F-S/T/Y-E maintained protein expression levels and complex formation similar to the wild-type DndFGH.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Effect of nonphosphorylatable mutations (T-to-A) or mimic phosphorylation (T-to-E) on protein expression.

The plasmid expressing QatABCD, DUF4297+HerA, SIR2+HerA, or their phosphomimetic/nonphosphorylatable derivatives was introduced into E. coli MG1655. QatC, HerA and DUF4297 in the QatABCD, SIR2+HerA and DUF4297+HerA modules were respectively fused with a 6 × His-tag at the C-terminus. The expression levels of QatC, HerA, DUF4297 and their derivatives were determined by Western blotting, with RpoB serving as an internal control.

Extended Data Fig. 7 The effect of JSS1_004 on the type I-E CRISPR–Cas system.

(a) The promoters of cas3 and casABCDE in the XTG103 genome were switched to the Ptac (blue) and PBAD (green) promoters, which could be induced by IPTG and arabinose, respectively, to generate a CC10 mutant. Plasmids pPT246 and pPT247 carry spacers sp-ATG and sp-AAG, respectively, which target different protospacers with 5′-ATG-3′ and 5′-AAG-3′ protospacer-adjacent motifs (PAMs) in the genomes of phages JSS1 and JSS1Δ004. (b) EOPs, which were performed at least three times, of JSS1 and JSS1Δ004 were defined as the ratio of the phage PFUs formed on spacer-containing cells divided by that counted on spacer-lacking cells. Data represent the mean ± SD from three independent experiments. *P < 0.05; ****P < 0.0001. (c) Diagram of the strategy used to assess primed spacer acquisition from the incoming plasmid pPT205 or pPT206. pPT205 and pPT206 carry spacer sp1 from the CRISPR1 array with 5′-ATC-3′ and 5′-TAC-3′ as PAM sequences, respectively. pACYC184-derived pPT213 expresses JSS1_0041-262. (d) The spacer acquisition rate of cells in the presence or absence of the JSS1_0041-262 protein kinase was determined by the number of colonies with newly incorporated spacers out of 24 selected colonies. The means ± SDs of three independent experiments are shown. **P < 0.01; ****P < 0.0001. (e) Time course of the primed adaptation of cells with or without the JSS1_0041-262 protein kinase. (f) The spacer acquisition rate of cells harboring CasD or its nonphosphorylatable/phosphomimetic mutant was determined by the number of colonies with newly incorporated spacers out of 24 selected colonies. The means ± SDs of three independent experiments are shown. ***P < 0.001; NS, not significant. (g) The spectrum of primed adaptation. New spacers acquired from the forward and reverse DNA strands of pPT205 and pPT206 are indicated with red and green lines, respectively. (h) The spacer acquisition rate of cells harboring pPT248, targeting JSS1 and JSS1Δ004, was determined by the number of colonies with newly incorporated spacers out of 384 selected colonies (96 colonies per set). The means ± SDs of four independent experiments are shown. **P < 0.01.

Extended Data Fig. 8

JSS1_004 and its homologs are widespread in nature. (a) Phylogenetic analysis of JSS1_004. From the outer ring to the inner ring: the classification for the genus of the predicted host, the classification for the genus of phage and the phylogenetic analysis of JSS1_004. (b) Phage plaque assays on E. coli DH5α(pJTU1238, pWHU4390) using 5 μL of each serial tenfold dilution of phage T3Δgp0.7 and T3.

Extended Data Fig. 9 A schematic model of JSS1_004-mediated anti-defense.

Under evolutionary pressure from phages, bacteria have developed various defense mechanisms. To facilitate intracellular proliferation, phages have evolved JSS1_004, a versatile kinase, to circumvent defense mechanisms via protein phosphorylation strategies.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Results

Supplementary Tables 1–10

Supplementary Tables 1–10.

Source data

Source Data Figs. 1–5, and Source Data Extended Data Figs. 1–8

Statistical source data, unprocessed plates, blots, gels and images of Figs. 1–5 and Extended Data Figs. 1–8.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, S., Chen, C., Huang, W. et al. A widespread phage-encoded kinase enables evasion of multiple host antiphage defence systems. Nat Microbiol 9, 3226–3239 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-024-01851-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-024-01851-2

This article is cited by

-

A DNA phosphorothioation pathway via adenylated intermediate modulates Tdp machinery

Nature Chemical Biology (2025)