Abstract

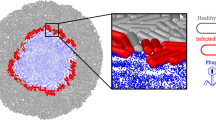

To overtake competitors, microbes produce and secrete secondary metabolites that kill neighbouring cells and sequester nutrients. This metabolite-mediated competition probably evolved in complex microbial communities in the presence of viral pathogens. We therefore hypothesized that microbes secrete natural products that make competitors sensitive to phage infection. We used a binary-interaction screen and chemical characterization to identify a secondary metabolite (coelichelin) produced by Streptomyces sp. that sensitizes its soil competitor Bacillus subtilis to phage infection in vitro. The siderophore coelichelin sensitized B. subtilis to a panel of lytic phages (SPO1, SP10, SP50, Goe2) via iron sequestration, which prevented the activation of B. subtilis Spo0A, the master regulator of the stationary phase and sporulation. Metabolomics analysis revealed that other bacterial natural products may also provide phage-mediated competitive advantages to their producers. Overall, this work reveals that synergy between natural products and phages can shape the outcomes of competition between microbes.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The genome sequence of strain I8-5 is available on NCBI (accession number JAYMFC000000000). The 16S sequences of the other plaque-enlarging bacteria are available on NCBI (I8-5: GenBank OR902106; Am9: GenBank PQ178887; Am23: GenBank PQ178944; Am62: GenBank PQ178965; R1B3: GenBank PQ178995; I8-24: GenBank PQ179041). Source data for plaque measurements are available on figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27269481 (ref. 68). Any further requests for data should be addressed to the corresponding author (jpgerdt@iu.edu).

References

Hibbing, M. E., Fuqua, C., Parsek, M. R. & Peterson, S. B. Bacterial competition: surviving and thriving in the microbial jungle. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8, 15–25 (2010).

Ghoul, M. & Mitri, S. The ecology and evolution of microbial competition. Trends Microbiol. 24, 833–845 (2016).

Westhoff, S., Kloosterman, A. M., Hoesel, S. F. A. V., Wezel, G. P. V. & Rozen, D. E. Competition sensing changes antibiotic production in Streptomyces. mBio 12, e02729-20 (2021).

Valle, J. et al. Broad-spectrum biofilm inhibition by a secreted bacterial polysaccharide. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 12558–12563 (2006).

Kramer, J., Özkaya, Ö. & Kümmerli, R. Bacterial siderophores in community and host interactions. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 18, 152–163 (2020).

Suttle, C. A. The significance of viruses to mortality in aquatic microbial communities. Microb. Ecol. 28, 237–243 (1994).

Koskella, B. & Meaden, S. Understanding bacteriophage specificity in natural microbial communities. Viruses 5, 806–823 (2013).

Hampton, H. G., Watson, B. N. J. & Fineran, P. C. The arms race between bacteria and their phage foes. Nature 577, 327–336 (2020).

Otsuji, N., Sekiguchi, M., Iijima, T. & Takagi, Y. Induction of phage formation in the lysogenic Escherichia coli K-12 by mitomycin C. Nature 184, 1079–1080 (1959).

Jancheva, M. & Böttcher, T. A metabolite of Pseudomonas triggers prophage-selective lysogenic to lytic conversion in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 8344–8351 (2021).

Silpe, J. E., Wong, J. W. H., Owen, S. V., Baym, M. & Balskus, E. P. The bacterial toxin colibactin triggers prophage induction. Nature 603, 315–320 (2022).

Hardy, A., Kever, L. & Frunzke, J. Antiphage small molecules produced by bacteria – beyond protein-mediated defenses. Trends Microbiol. 31, 92–106 (2023).

Lautru, S., Deeth, R. J., Bailey, L. M. & Challis, G. L. Discovery of a new peptide natural product by Streptomyces coelicolor genome mining. Nat. Chem. Biol. 1, 265–269 (2005).

Williams, J. C. et al. Synthesis of the siderophore coelichelin and its utility as a probe in the study of bacterial metal sensing and response. Org. Lett. 21, 679–682 (2019).

Challis, G. L. & Ravel, J. Coelichelin, a new peptide siderophore encoded by the Streptomyces coelicolor genome: structure prediction from the sequence of its non-ribosomal peptide synthetase. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 187, 111–114 (2000).

Hider, R. C. & Kong, X. Chemistry and biology of siderophores. Nat. Prod. Rep. 27, 637–657 (2010).

May, J. J., Wendrich, T. M. & Marahiel, M. A. The dhb operon of Bacillus subtilis encodes the biosynthetic template for the catecholic siderophore 2,3-dihydroxybenzoate-glycine-threonine trimeric ester bacillibactin. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 7209–7217 (2001).

Schneider, R. & Hantke, K. Iron-hydroxamate uptake systems in Bacillus subtilis: identification of a lipoprotein as part of a binding protein-dependent transport system. Mol. Microbiol. 8, 111–121 (1993).

Abergel, R. J., Zawadzka, A. M., Hoette, T. M. & Raymond, K. N. Enzymatic hydrolysis of trilactone siderophores: where chiral recognition occurs in enterobactin and bacillibactin iron transport. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 12682–12692 (2009).

Dertz, E. A., Xu, J., Stintzi, A. & Raymond, K. N. Bacillibactin-mediated iron transport in Bacillus subtilis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 22–23 (2006).

Ollinger, J., Song, K.-B., Antelmann, H., Hecker, M. & Helmann, J. D. Role of the fur regulon in iron transport in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 188, 3664–3673 (2006).

Gallet, R., Kannoly, S. & Wang, I.-N. Effects of bacteriophage traits on plaque formation. BMC Microbiol. 11, 181 (2011).

Zang, Z., Park, K. J. & Gerdt, J. P. A metabolite produced by gut microbes represses phage infections in Vibrio cholerae. ACS Chem. Biol. 17, 2396–2403 (2022).

Bokinsky, G. et al. HipA-triggered growth arrest and beta-lactam tolerance in Escherichia coli are mediated by RelA-dependent ppGpp synthesis. J. Bacteriol. 195, 3173–3182 (2013).

Woody, M. A. & Cliver, D. O. Effects of temperature and host cell growth phase on replication of F-specific RNA coliphage Q beta. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 61, 1520–1526 (1995).

Bryan, D., El-Shibiny, A., Hobbs, Z., Porter, J. & Kutter, E. M. Bacteriophage T4 infection of stationary phase E. coli: life after log from a phage perspective. Front. Microbiol. 7, 1391 (2016).

Los, M. et al. Effective inhibition of lytic development of bacteriophages lambda, P1 and T4 by starvation of their host, Escherichia coli. BMC Biotechnol. 7, 13 (2007).

Rittershaus, E. S. C., Baek, S.-H. & Sassetti, C. M. The normalcy of dormancy: common themes in microbial quiescence. Cell Host Microbe 13, 643–651 (2013).

Phillips, Z. E. & Strauch, M. A. Bacillus subtilis sporulation and stationary phase gene expression. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 59, 392–402 (2002).

Ireton, K., Rudner, D. Z., Siranosian, K. J. & Grossman, A. D. Integration of multiple developmental signals in Bacillus subtilis through the Spo0A transcription factor. Genes Dev. 7, 283–294 (1993).

Grandchamp, G. M., Caro, L. & Shank, E. A. Pirated siderophores promote sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 83, e03293–03216 (2017).

Qin, Y. et al. Heterogeneity in respiratory electron transfer and adaptive iron utilization in a bacterial biofilm. Nat. Commun. 10, 3702 (2019).

Molle, V. et al. The Spo0A regulon of Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 50, 1683–1701 (2003).

Zhu, M. et al. A fitness trade-off between growth and survival governed by Spo0A-mediated proteome allocation constraints in Bacillus subtilis. Sci. Adv. 9, eadg9733 (2023).

Hoch, J. A. Regulation of the phosphorelay and the initiation of sporulation in Bacillus subtilis. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 47, 441–465 (1993).

Măgălie, A. et al. Phage infection fronts trigger early sporulation and collective defense in bacterial populations. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.05.22.595388 (2024).

Schwartz, D. A., Lehmkuhl, B. K. & Lennon, J. T. Phage-encoded sigma factors alter bacterial dormancy. mSphere 7, e00297-22 (2022).

Tan, I. S. & Ramamurthi, K. S. Spore formation in Bacillus subtilis. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 6, 212–225 (2014).

Pires, D. P., Melo, L. D. R. & Azeredo, J. Understanding the complex phage–host interactions in biofilm communities. Annu. Rev. Virol. 8, 73–94 (2021).

Banse, A. V., Chastanet, A., Rahn-Lee, L., Hobbs, E. C. & Losick, R. Parallel pathways of repression and antirepression governing the transition to stationary phase in Bacillus subtilis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 15547–15552 (2008).

McLoon, A. L., Guttenplan, S. B., Kearns, D. B., Kolter, R. & Losick, R. Tracing the domestication of a biofilm-forming bacterium. J. Bacteriol. 193, 2027–2034 (2011).

van Sinderen, D. et al. comK encodes the competence transcription factor, the key regulatory protein for competence development in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 15, 455–462 (1995).

González-Pastor, J. E., Hobbs, E. C. & Losick, R. Cannibalism by sporulating bacteria. Science 301, 510–513 (2003).

Ellermeier, C. D., Hobbs, E. C., Gonzalez-Pastor, J. E. & Losick, R. A three-protein signaling pathway governing immunity to a bacterial cannibalism toxin. Cell 124, 549–559 (2006).

Straight, P. D., Willey, J. M. & Kolter, R. Interactions between Streptomyces coelicolor and Bacillus subtilis: role of surfactants in raising aerial structures. J. Bacteriol. 188, 4918–4925 (2006).

Hemphill, H. E. & Whiteley, H. R. Bacteriophages of Bacillus subtilis. Bacteriol. Rev. 39, 257–315 (1975).

Willms, I. M., Hoppert, M. & Hertel, R. Characterization of Bacillus subtilis viruses vB_BsuM-Goe2 and vB_BsuM-Goe3. Viruses 9, 146 (2017).

Liu, C. G. et al. Phage–antibiotic synergy is driven by a unique combination of antibacterial mechanism of action and stoichiometry. mBio 11, e01462-20 (2020).

Niehus, R., Picot, A., Oliveira, N. M., Mitri, S. & Foster, K. R. The evolution of siderophore production as a competitive trait. Evolution 71, 1443–1455 (2017).

Henriques, A. O. & Moran, C. P. Jr Structure, assembly, and function of the spore surface layers. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 61, 555–588 (2007).

Nicholson, W. L., Munakata, N., Horneck, G., Melosh, H. J. & Setlow, P. Resistance of Bacillus endospores to extreme terrestrial and extraterrestrial environments. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64, 548–572 (2000).

Lennon, J. T. & Jones, S. E. Microbial seed banks: the ecological and evolutionary implications of dormancy. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9, 119–130 (2011).

Khanna, K., Lopez-Garrido, J. & Pogliano, K. Shaping an endospore: architectural transformations during Bacillus subtilis sporulation. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 74, 361–386 (2020).

Schwartz, D. A. et al. Human-gut phages harbor sporulation genes. mBio 14, e0018223 (2023).

Xiong, Q. et al. Autoinducer-2 relieves soil stress-induced dormancy of Bacillus velezensis by modulating sporulation signaling. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 10, 117 (2024).

Aldape, M. J. et al. Fidaxomicin reduces early toxin A and B production and sporulation in Clostridium difficile in vitro. J. Med. Microbiol. 66, 1393–1399 (2017).

Golonka, R., Yeoh, Beng, S. & Vijay-Kumar, M. The iron tug-of-war between bacterial siderophores and innate immunity. J. Innate Immun. 11, 249–262 (2019).

Schindelin, J. et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 676–682 (2012).

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120 (2014).

Prjibelski, A., Antipov, D., Meleshko, D., Lapidus, A. & Korobeynikov, A. Using SPAdes De Novo Assembler. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 70, e102 (2020).

Seemann, T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 30, 2068–2069 (2014).

Blin, K. et al. AntiSMASH 7.0: new and improved predictions for detection, regulation, chemical structures and visualisation. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, W46–W50 (2023).

Mazzocco, A., Waddell, T. E., Lingohr, E. & Johnson, R. P. in Bacteriophages: Methods and Protocols Volume 1: Isolation, Characterization, and Interactions (eds Clokie, M. & Kropinski, A.) 81−85 (Humana Press, 2009).

Siala, A., Hill, I. R. & Gray, T. R. G. Populations of spore-forming bacteria in an acid forest soil, with special reference to Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology 81, 183–190 (1974).

Yasbin, R. E. & Young, F. E. Transduction in Bacillus subtilis by bacteriophage SPP1. J. Virol. 14, 1343–1348 (1974).

Konkol, M. A., Blair, K. M. & Kearns, D. B. Plasmid-encoded ComI inhibits competence in the ancestral 3610 strain of Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 195, 4085–4093 (2013).

Koo, B.-M. et al. Construction and analysis of two genome-scale deletion libraries for Bacillus subtilis. Cell Syst. 4, 291–305.e297 (2017).

Zang, Z. et al. Streptomyces secretes a siderophore that sensitizes competitor bacteria to phage infection. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27269481 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We thank A. Măgălie (Georgia Institute of Technology) and J. Weitz (University of Maryland) for helpful discussions; the Bacillus Genomic Stock Center (Ohio State University), the Félix d’Hérelle Reference Center for Bacterial Viruses (University of Laval), R. Hertel (University of Goettingen) and D. Rudner (Harvard Medical School) for providing bacteria and phages; and E. M. Nolan (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) for providing enterobactin. The research was supported by a research starter grant from the American Society of Pharmacognosy to J.P.G. and a National Science Foundation CAREER award (IOS-2143636) to J.P.G. Research support was also provided by the National Science Foundation (DEB-1934554 to J.T.L. and D.A.S.; DBI-2022049 to J.T.L.), the US Army Research Office (W911NF-22-1-0014 and W911NF-22-S-0008 to J.T.L.) and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (80NSSC20K0618 to J.T.L.). Z.Z. was supported in part by the John R. and Wendy L. Kindig Fellowship. K.J.P. and the Laboratory for Biological Mass Spectrometry were supported by the Indiana University Precision Health Initiative. The 500 MHz NMR and 600 MHz spectrometer of the Indiana University NMR facility were supported by NSF grant CHE-1920026, and the Prodigy probe was purchased in part with support from the Indiana Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute, funded in part by NIH Award TL1TR002531.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.Z. and J.P.G. conceptualized the project. Z.Z., D.A.S. and J.P.G. developed the methodology. Z.Z., C.Z., K.J.P. and R.P. conducted investigations. Z.Z. and J.P.G. wrote the original draft of the paper. Z.Z., C.Z., D.A.S., J.T.L. and J.P.G. reviewed and edited the paper. Z.Z. and J.P.G. performed visualization. J.T.L. and J.P.G. supervised the project. J.T.L. and J.P.G. acquired funding.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Microbiology thanks Anna Dragos, Justin Nodwell and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Coelichelin is the active metabolite that promotes phage predation.

(a) Scheme of the binary-interaction screen. (b) Negative mode electrospray ionization MS spectra of active fraction 1 (left) and active fraction 2 (right). The shared peaks are highlighted red. (c) MS/MS spectrum of the m/z 566.2783 species. Key fragments are annotated with their associated peak, and their losses are highlighted in red. (d) MS/MS spectrum of the m/z 619.1885 species. Key fragments are annotated with their associated peak, and their losses are highlighted in red. (e) Comparison of the Streptomyces sp. I8-5 coelichelin biosynthetic gene cluster with the reported one from S. coelicolor A3(2). The percent identity between each pair of genes is shown with shading (all were >75%). The modules of the coelichelin non-ribosomal peptide synthetase are shown in the lower region of the panel. The three modules are responsible for installation of d-δ-N-formyl-δ-N-hydroxyornithine (d-hfOrn), d-allo-threonine (d-allo-Thr), and l-δ-N-hydroxyornithine (l-hOrn), respectively. The adenylation domains (A), thiolation and peptide carrier proteins (CP), condensation domains (C), and epimerization domains (E) are shown.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Coelichelin isolation from I8-5 supernatant.

(a) Isolation scheme. (b) UV chromatogram at 210 nm. Water was used as the blank. (c) The averaged MS spectrum at positive mode between retention time 13.5 ~ 14.8 min. (d) The averaged MS spectrum at negative mode between retention time 13.5 ~ 14.8 min. M represents coelichelin.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Multiple pathways regulated by Spo0A are important for the plaque enlargement phenotype caused by iron sequestration.

(a) Pathways regulated by Spo0A. (b) The x-axis shows the plaque size ratio between mutant and wild type (WT) under iron-rich conditions ( − EDDHA). The y-axis shows the plaque size ratio between iron-limited (6 mM EDDHA treated [2 µL]) and iron-rich conditions ( − EDDHA) of different mutants. Water was used as the −EDDHA control. Data are represented as the average ratio ± SEM calculated from at least four individual plaques of each condition.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Ferrioxamine E alone has no substantial effect on plaque size, B. subtilis growth, and Spo0A activation.

(a) The average plaque areas of SPO1 on B. subtilis were measured when treated with or without ferrioxamine E (2 µl of 20 mM) as an excess iron source. Data are represented as the average ± SEM from three independent biological replicates. Circles show the values of each biological replicate and at least 21 plaques were selected for each replicate. (b) The colony forming units of B. subtilis were measured when infected by SPO1 phages, treated with or without ferrioxamine E (2 µl of 20 mM) as an excess iron source. Data are represented as the average ± SEM from three independent biological replicates. Circles show the values of each biological replicate. (c) The impact of ferrioxamine E (2 µl of 20 mM) on B. subtilis sporulation (an indicator of Spo0A activation). Data are represented as the average ± SEM from three independent biological replicates. Circles show the values of each biological replicate.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Coelichelin is not ubiquitously produced by all plaque-enlarging bacteria.

The conditioned media resulting from the fermentation of 4 plaque-enlarging bacteria (collected at different time points) were subjected to LC-MS analysis. The extracted ion chromatogram of coelichelin is shown here. No coelichelin was detected in the conditioned medium of Am23, suggesting that it does not produce coelichelin but instead an unknown phage-promoting siderophore.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–10 and Table 1.

Supplementary Tables 2–5

Supplementary Tables 2–5.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Zang, Z., Zhang, C., Park, K.J. et al. Streptomyces secretes a siderophore that sensitizes competitor bacteria to phage infection. Nat Microbiol 10, 362–373 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-024-01910-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-024-01910-8

This article is cited by

-

A global soil plasmidome resource unveils functional and ecological roles of plasmids in soil microbiomes

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Co-cultivation strategies for natural product discovery from actinomycetes: unlocking silent secondary metabolism with mycolic acid-containing bacteria

World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology (2025)