Abstract

The interdisciplinary nature of microbiome research, coupled with the generation of complex multi-omics data, makes knowledge sharing challenging. The Strengthening the Organization and Reporting of Microbiome Studies (STORMS) guidelines provide a checklist for the reporting of study information, experimental design and analytical methods within a scientific manuscript on human microbiome research. Here, in this Consensus Statement, we present the standards for technical reporting in environmental and host-associated microbiome studies (STREAMS) guidelines. The guidelines expand on STORMS and include 67 items to support the reporting and review of environmental (for example, terrestrial, aquatic, atmospheric and engineered), synthetic and non-human host-associated microbiome studies in a standardized and machine-actionable manner. Based on input from 248 researchers spanning 28 countries, we provide detailed guidance, including comparisons with STORMS, and case studies that demonstrate the usage of the STREAMS guidelines. STREAMS, like STORMS, will be a living community resource updated by the Consortium with consensus-building input of the broader community.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Microbiome research is inherently interdisciplinary, spanning hosts (humans, animals or plants) and environments and capturing impacts ranging from health and disease to ecosystem function, agriculture and food security1,2,3,4. While human microbiome research has flourished due to heavy investment in research infrastructure and broad public recognition, resourcing for microbiome science outside human health has lagged5. Environmental microbiome research necessitates unique considerations, as it combines cross-disciplinary techniques, field sampling campaigns and insights from microbiology, data science, bioinformatics and ecology, among other areas. The data and metadata associated with microbiome studies continue to be difficult to capture and report, especially as the utilization of multi-omics methodologies has advanced, generating large, complex datasets6. Furthermore, ensuring data are deposited and available for reuse according to the Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable (FAIR) principles presents challenges for many researchers when navigating data repository submissions and when working with incomplete metadata7. While there have been consistent calls from the community to promote more standardization across the entire microbiome research lifecycle, several barriers remain8,9,10,11,12. Researchers, publishers, funders and data repositories must be brought together to establish consensus guidelines that address the unique complexities of environmental and synthetic microbiome data generation, analysis and sharing.

Community-driven efforts to develop best practices, reporting guidelines and standards have advanced how microbiome data are shared and reused. When the Genomic Standards Consortium developed the Minimum Information about any (x) Sequence (MIxS) standards for metadata management in 2011, it quickly became a foundation for standardized microbiome metadata capture13,14,15. More recently, several genome-based community-driven efforts have advanced cross-study comparisons, including standards for viral and prokaryotic genomes16,17. The Strengthening the Organization and Reporting of Microbiome Studies (STORMS) checklist leverages the MIxS standards as well as the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) and Strengthening the Reporting of Genetic Association Studies (STREGA) guidelines to provide a framework for the reporting of human microbiome studies18,19,20. The microbiome research community has already widely adopted the STORMS checklist. However, these guidelines apply only to human-associated microbiome studies, and there has been no equivalent generated for environmental microbiomes.

To address the current gaps in comprehensive guidelines for environmental (for example, terrestrial, aquatic, atmospheric or engineered), non-human host-associated (for example, animal- or plant-associated) and synthetic microbiome research, we present the Standards for Technical Reporting in Environmental and host-Associated Microbiome Studies (STREAMS) guidelines. These guidelines were constructed using the STORMS checklist as a framework and were iterated using extensive community feedback. The STREAMS guidelines and associated materials provide authors with clear, actionable recommendations for manuscript preparation and data sharing, while offering reviewers a structured framework for evaluating methodology and data quality. The STORMS checklist and its subsequent iterations will continue to support human-associated microbiome studies, whereas the STREAMS guidelines provide guidance to microbiomes not directly associated with human subjects. The STORMS and STREAMS guidelines will be collaboratively updated to maintain synergy. These guidelines were created to lower barriers to proper microbiome data management and reporting by providing a clear and structured framework. They are designed to foster greater standardization and promote FAIR data principles, ultimately maximizing the utility and impact of microbiome data for the broader scientific community.

Methodology

In June 2024, we convened the Microbiome Data Management in Action workshop in Atlanta, USA, which brought together 50 invited microbiome researchers, publishers, funders and data repository representatives to discuss the current state of microbiome data management and reporting21. More details regarding the workshop agenda, participants, panels, presentations and discussions are available in the Microbiome Data Management in Action workshop report21. A large focus of the workshop was adapting the human-associated microbiome STORMS checklist to make it applicable to these systems. A preliminary review of the STORMS guidelines revealed that many of its items would need to be revised based on differences in terminology, data access requirements, metadata standards and conventions within environmental microbiome research compared with human-associated studies. Several limitations with the STORMS checklist, such as the limited information about metabolomics and proteomics, varied interpretations of STORMS Item 6.0 related to causal inference, and the fact that several items may be outdated, were also presented by the STORMS lead author. Six breakout groups worked on the checklist, and the suggested changes were discussed and concatenated. This led to a first draft version of the STREAMS guidelines.

Obtaining community feedback was a priority for the STREAMS effort, and therefore, the first draft of the guidelines was circulated across the broader microbiome research community through targeted emails, social media posts, microbiome-relevant newsletters and the STREAMS website https://streamsmicrobiome.org/). A modified Delphi methodology was implemented, featuring multiple rounds of community feedback reviewed by a working group formed by attendees of the workshop. We designed and distributed a feedback form that included prompts about suggested changes, revisions and items to consider as ‘must-keep’ in the STREAMS draft, or respondents could comment directly in the Google Sheet with the STREAMS draft. From the first round of community feedback via direct comments and responses to the feedback form, we obtained over 700 comments that were discussed and implemented, or were deemed to be infeasible (for example, the feedback was too prescriptive or did not align with existing reporting guidelines or standards). All comments from this first round were addressed by members of the STREAMS working group who continued to meet biweekly. Subsequently, an updated second draft of the STREAMS guidelines was then circulated, which received 400 additional comments, all of which were responded to and implemented into the consensus guidelines whenever possible and when agreed upon by the working group. A few examples of comments received during the rounds of feedback that were incorporated into the final guidelines include: “Software: would be good to specify actual parameters used rather than ‘default parameters’ as the defaults can change over time”; “Item 3: For agricultural studies, greenhouse studies sometimes serve as an in-between for field and laboratory studies. Greenhouse or semi-controlled spaces could be added as a category.”; “Similar to the STORMS checklist, having exemplary checklists for recent or past studies would be very helpful.”. There were very few instances of conflicting comments, and in those cases, the STREAMS working group and expert researchers in the microbiome research field were consulted to determine the optimal course of action. Overall, 248 researchers from 28 countries provided feedback, although we acknowledge the lack of representation from researchers in Africa and parts of Asia and South America. Together, this group spans a range of career stages, works with various sample and data types and represents varied facets of microbiome research.

Checklist

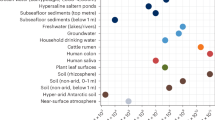

The STREAMS guidelines (Supplementary Table 1) consist of 67 items organized into six sections aligned with the architecture of a scientific manuscript, reflecting which section they pertain to (Fig. 1). The guidelines are also publicly available via Zenodo22, on the STREAMS website and as a machine-actionable data management plan (DMP) building tool within a free, publicly available web resource hosted by the California Digital Library called DMP Tool23 (available under Templates, as ‘STREAMS Microbiome Guidelines DMP Tool template’). Each STREAMS item comprises eight elements: its number, name, the recommendation, where the item derived from (for example, if derived from another existing standard), additional guidance, example(s) and two manuscript-associated columns to be used by authors or reviewers for noting if the item is reported in the manuscript and, if so, in which section. The ‘Item Source’ column references STORMS, the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), MIxS, the Environment Ontology (ENVO), the Open Biomedical Ontologies Foundry, the Chemical Analysis Working Group of the Metabolomics Standards Initiative, STROBE or STREGA, or denotes if the item is considered new for STREAMS. While not all studies may capture every reporting detail, the intent of the STREAMS guidelines is to be broadly descriptive and inclusive of diverse use cases spanning environmental, synthetic and non-human host-associated microbiomes. STREAMS is intended to act as a reflective framework for assessing manuscripts, and the content, item order and organization are not designed to be strict requirements.

a, The guidelines encompass microbiomes ranging from terrestrial and aquatic (environmental) to synthetic and non-human host-associated environments. b, The six key sections include (1) abstract, (2) introduction, (3) methods, (4) results, (5) discussion and (6) other information. Figure created with BioRender.com.

Abstract (1.0–1.5)

The Abstract section (Items 1.0–1.5) provides guidance on how to organize and report sufficient information in an abstract for environmental, non-human host-associated or synthetic microbiome studies. Abstracts are often replicated across platforms (for example, associated with the data in a data repository), magnifying their importance as independent summaries of key study elements. Overall guidance for the abstract organization is provided along with notes regarding graphical abstracts (Item 1.0). Items 1.1, 1.2, 1.4 and 1.5 encompass the study design, environments and samples, experiments or methodology (including specific information about omics methods utilized), the analyses performed and the overall results of the study and their importance. As noted throughout the guidelines, several items are applicable only to host-associated studies. The first such instance appears in Item 1.3, which requests a summary of host information.

Introduction (2.0–2.1)

The Introduction section (Items 2.0–2.1) parallels that of the original STORMS checklist. This section requests that authors describe the background and rationale for their study (Item 2.0) in the context of previous work that has been conducted in their specific field. The synthesis of previous publications and datasets in their area of research should highlight any knowledge gaps. Researcher hypotheses, objectives or research questions are also requested to be included in the Introduction (Item 2.1), which are encouraged to relate to the aforementioned knowledge gaps and broader importance of the reported study.

Methods (3.0–8.5)

Methods comprise a majority of the checklist, as outlined below.

Study and sample information (3.0–3.6)

The ‘Study and sample information’ items (3.0–3.6) request detailed information on the study design, any associated host(s), any datasets that were reused for the study, and the samples that were analysed. This section is designed to capture sufficient contextual information about the study. The overall study design should be stated (Item 3.0) and should acknowledge if the study includes meta-analyses, combined analyses or involves datasets derived from previously published work. The sample type(s) as well as any associated sample metadata are requested in Item 3.1, which also necessitates the inclusion of specific information on how any relevant synthetic communities (SynComs) were generated, as well as accurate citation information on datasets that have been reused12. The ‘Environmental context and geographic location’ item (Item 3.2) requires that the author states where the samples originated. This item generated considerable discussion within the STREAMS Consortium, as some researchers preferred requiring geographic coordinates, while others noted that ethical and privacy considerations may prevent this. The consortium decided on strongly encouraging the inclusion of coordinates and requiring a justification if they cannot be provided. The MIxS standards as well as ENVO are referenced in this item to standardize how the environmental context and the geographic location are reported24. Item 3.3 requests any relevant dates, including when samples were collected, over what time period, the frequency of sampling and other temporal factors (for example, seasonality). Item 3.4 applies only to host-associated studies and is intended to capture as much detailed information about the host(s) as possible. Comprehensive, well-researched and detailed information on the ethics of the study design must be reported (Item 3.5). This item includes guidance on reporting permits, permissions and sampling ethics. The CARE principles for Indigenous data governance (Collective benefit, Authority to control, Responsibility and Ethics) are referenced here, and researchers are expected to adhere to these guidelines and ensure Indigenous data sovereignty whenever applicable25. Item 3.6 refers to any treatments or conditions that the sampling environment(s) or host(s) were subjected to, and the relevant MIxS references are included in the additional guidance for this item26,27,28.

Sample collection (3.7–3.9)

Authors should report detailed information regarding sample collection methods and metadata, including if previously published protocols were followed (Item 3.7). Specifics regarding the tools that were used, the host body site or environmental niche sampled, and potential sample destruction can be critical to a comprehensive understanding of the samples and the reproducibility of the methods and should also be provided. Information on sample eligibility and selection criteria should also be included (Item 3.8), which leads to reporting on the final analytic sample size (Item 3.9).

Experimental information (4.0–4.6)

Information on sample storage, preservation, transportation and shipping should be included (Items 4.0 and 4.1). In terms of experimental steps, nucleic acid, protein and/or metabolite extraction methods should be reported (Item 4.2), along with steps relating to experimental manipulations, sample processing and culturing (Item 4.3). Information on nucleic acid library preparation protocols was separated into another item to better align with submission requirements to data repositories such as the NCBI Sequence Read Archive29 (Item 4.4). Methods for enriching or depleting samples should be discussed in depth (Item 4.5), including if amplification was used and, if so, the targeted region and primer sequences (Item 4.6). These items are of particular importance to microbiome samples, as each depletion or enrichment method could exclude signatures from some members of the microbial community and can have particular biases.

Controls and quality information (5.0–6.2)

Feedback from the community suggested that the guidelines be extremely explicit for items referring to controls and replicates. Therefore, the ‘Control and quality information’ categories were split into several items (Items 5.0–6.2). Any positive (Item 5.0) and negative (Item 5.1) controls should include detailed descriptions, specifying what they were and at which stage they were implemented. Justification should be provided if no positive or negative controls were included. Information on quantity and quality assessments of samples, nucleic acids, proteins and metabolites should be included in Item 6.0, referencing any pre-existing protocols. Any laboratory-based strategies utilized to minimize and identify contamination can be specifically stated (Item 6.1) or discussed throughout the Methods at each step. Biological and technical replicates should be discussed (Item 6.2), and the additional guidance recommends that authors explain why certain replicates were included and how they were incorporated into bioinformatics and statistical analyses.

Omics data generation (6.3–6.6)

Items 6.3–6.6 encompass omics data generation, specifically for sequencing (Item 6.3) and mass spectrometry (Item 6.4) applications30. Specificity in the information provided in this section is paramount as these metadata can directly affect results and interpretations. Vendor and kit information as well as established protocols should be referenced whenever possible. For the sequencing information, synergy with specific NCBI Sequence Read Archive submission fields and requirements is noted to assist researchers. Item 6.5 requests information on other contextual or linked datasets and how these relate to the study and the omics data. While other omics or data types may not be fully encompassed by the guidelines, additional information would be required for analyses involving these datasets. Anticipated or potential batch effects (Item 6.6) should also be reported for the sampling and processing steps outlined in earlier Items as well as for the omics and data generation Items in this section (Items 6.3–6.5).

Data analysis (7.0–7.9)

Feedback from the community indicated that a key challenge for microbiome data reuse has been a lack of transparency regarding specifics about bioinformatics tools, workflows, parameters and code in associated publications. Therefore, we split the bioinformatics, data analysis and statistical processing steps into ten detailed items. Information regarding all bioinformatics analyses and steps included in the study should be reported as noted in Item 7.031. Standardization between workflow runs is encouraged, and all relevant processing metadata should be included so that any researcher can fully replicate all bioinformatics steps. Quality control information should be reported, including how low-quality data were filtered out and the performance of any negative or positive controls that were included (Item 7.1). Normalization processes can often differ between studies, and this information should be specifically reported (Item 7.2). Many STREAMS Consortium members appreciated the inclusion of database information in the STORMS guidelines but requested that this be expanded to its own item with more guidance. Item 7.3 captures database information for taxonomic classifications as well as metabolite and protein identification. Database names, versions, dates of creation and access, digital object identifiers, citations and/or relevant links are requested. Information on the construction of custom databases should also be included.

The statistical methods used in the study should be exhaustively reported (Item 7.4) and should include details about how calculations were performed, any transformations that were performed and why particular statistical tests were chosen32. Item 7.5 is critical for research transparency relating to missing information. The potential for biases and confounding variables as well as methods utilized to minimize these effects are suggested to be included here in the Methods (Item 7.6), and can be expanded upon in the Discussion (Item 11.2) in the context of overall study limitations33. If any subgroups were formed during analysis, Item 7.7 should detail how and why these subgroups were created. Information on any sensitivity analyses that were performed, in particular those that may impact results, should be reported in Item 7.8. Significance thresholds should be included as described in Item 7.9, and false discovery assessments are also recommended for reporting.

Access and reproducibility (8.0–8.5)

Access to the metadata, host data, raw data, processed data, software and code are all critical for adhering to the FAIR principles and ensuring reproducibility and reusability of microbiome studies. The metadata standards that were followed (for example, MIxS) and how the metadata can be accessed should be reported as indicated in Item 8.0, and justification should be provided if not all metadata are made publicly available34. If applicable, host information, data and metadata should also be directly linked in the publication, and details should be provided on how to link host data to the microbiome data (Item 8.1). All raw data (Item 8.2) and processed data (when applicable; Item 8.3) should also be made publicly available in robust long-term databases. Item 8.4 outlines recommended details to include when reporting on the software, tools, workflows and code used to perform assessments and analyses, which should all be made publicly available whenever possible35. Item 8.5 closely matches the STORMS checklist to request information regarding the reproducibility of the methodologies and analyses used in the study36.

Results (9.0–10.3)

While microbiome research results can be presented in a myriad of ways, Items 9.0–10.3 provide recommendations for proper manuscript reporting of common types of results. Results and information relating to the environment(s), host(s) and sample(s), including the variables of interest (as well as potential confounding variables to the results), are requested in Item 9.0. Results, specifically from sequencing analyses, are encapsulated in Item 10.0, and results from positive and negative controls should be referenced. Results from other omics analyses (for example, metabolomics and proteomics) should also be reported in the context of any standards that were used to identify metabolites and proteins (Item 10.1). Item 10.2 relates to the methods reported in Item 7.4 and includes guidelines for reporting on the results of statistical analyses performed on the data. Item 10.3 provides overall guidance for figures, tables and captions.

Discussion (11.0–13.0)

The Discussion section is meant to be minimally prescriptive, and we recognize that each journal, researcher and group have unique approaches to Discussion sections. The STREAMS guidelines request a summary of the key results and how they relate to the overall study objective(s) (Item 11.0). This can also include if any hypotheses have been rejected or supported. Item 11.1 describes how interpretations of results can be reported, and how the results fit into the broader context of the field and other existing datasets. It is noted that caution should be used when including certain terms and language, and that formal definitions may need to be included37. The overall limitations of the study should be included, with an emphasis on areas of potential bias (Item 11.2). The generalizability of the study results should also be reported (Item 11.3); for example, authors should indicate how the results are expected to change—or remain the same—across different hosts or environments. Guidelines are also provided for the reporting of ongoing or future work (Item 12.0) and for overarching conclusions (Item 13.0).

Other information (14.0–18.0)

The ‘Other information’ section encompasses items that are typically required during journal submission. Journals may have different thresholds for awarding acknowledgements, but typically they are given to researchers who did not meet the criteria for authorship, or to other groups, facilities or institutions that provided assistance to the study (Item 14.0). As permitted by the publisher and authors’ affiliates, Indigenous land acknowledgements may also be reported here, along with other information described in Item 3.5. Item 14.1 provides guidance for how funding statements should be reported for each author. Any known or potentially perceived conflicts of interest must be reported to the journal following publisher guidance (Item 15.0). Proper management and reporting of supplementary information (Item 16.0) is often necessary to ensure FAIRness of the research, and this can often be overlooked by authors, reviewers and readers. Links to digital object identifiers and external supplementary information should be provided, and metadata, supplementary figures and data processing information should all be properly reported in this section. Similarly, information on how all the samples and data associated with the study can be accessed should be reported, along with information on how disparate datasets and information can be linked (Item 17.0). Finally, many journals now require the reporting of any machine learning or artificial intelligence (AI) methods that were utilized throughout the study (Item 18.0). We encourage authors to include this information in the Methods, as well as in the supplementary information section. Authors should describe the exact ways in which AI was used (for example, language translations, writing assistance and figure generation) and refer to journal-specific guidance for acceptable usage. We expect the guidance for this item to continuously evolve as AI usage becomes more prevalent, and as guidance and restrictions change.

Implementation

Throughout the process of creating STREAMS, it became clear that providing these guidelines during the manuscript writing process may be too late in the research process to ensure that the information and metadata noted in the STREAMS items are captured. Therefore, we constructed a STREAMS template through an existing DMP-building resource, the DMP Tool. While this template is not meant to be used directly as a DMP, it can assist in the creation of information recommended in the STREAMS guidelines. Any researcher can access the ‘STREAMS Microbiome Guidelines’ DMP Tool template to help craft a machine-actionable template, automating the process of pulling institutional information and linking persistent identifiers, for work they plan to perform or have already conducted.

To ensure these guidelines are broadly comprehensible and user-friendly, we created an overall STREAMS User Guide document (Supplementary Note 1), as well as a tutorial video that is available on the STREAMS website (https://streamsmicrobiome.org). A simplified STREAMS document is also available on the website as a quick checklist for those already familiar with the comprehensive guidelines, or for those who prefer a less detailed version while still referencing the main STREAMS guidelines for context. A list of acronyms used in STREAMS, along with relevant links, is also available (Supplementary Note 2).

To demonstrate how the STREAMS guidelines can be applied, we selected eight publications spanning various environmental, synthetic and non-human host-associated microbiome studies (Table 1 and Supplementary Tables 2–9). Examples for each STREAMS item, where applicable, as well as their respective locations in the manuscripts were manually recorded on a STREAMS template. Each completed exemplar was internally reviewed for accuracy and made available here and on the STREAMS website.

Discussion

Reporting guidelines and checklists have demonstrated their efficacy across various disciplines, and the STORMS checklist continues to be adopted across human microbiome research and by funding agencies and publishers18. Using STORMS as the template for STREAMS leverages the successes seen with STORMS, while aiming to provide an effective checklist for necessary study, experimental design and analytical methods reporting for environmental, non-human host-associated and synthetic microbiomes. We also recognize the impact and utility of previously generated standards such as STROBE, STREGA, ENVO and MIxS, which were implemented throughout the STREAMS guidelines whenever possible14,19,20,24. A more detailed explanation of the Item Source column in STREAMS—including its connections to other standards and initiatives, as well as a comparison between STORMS and STREAMS—is also available (Supplementary Note 3).

While the items listed in the guidelines do not capture information relevant to every study, they are designed to be generalizable without being exhaustive. There are several noted limitations of these guidelines. There is the possibility of ‘checklist fatigue’ due to the length and amount of content captured in the STREAMS guidelines. The simplified version of STREAMS (https://streamsmicrobiome.org) was designed to help with this; however, we recognize that these guidelines may still appear overwhelming. The order of the items may also be perceived as a strict recommendation for manuscript ordering and flow, which could potentially hinder creativity and prevent non-traditional manuscript formatting. In addition, STREAMS may be interpreted by some as a set of strict requirements to assess compliance, rather than a reflective framework as it is intended. It can also be difficult to retroactively obtain the information or perform steps recommended by STREAMS. If researchers are not aware of these guidelines until the manuscript submission step, critical reporting information could be missed. We also recognize that the specific caveats associated with various research areas, environments, experiments or contexts may not be captured in sufficient detail by these guidelines.

Throughout the development of STREAMS, we prioritized community feedback to generate consensus. The inherent interdisciplinarity of microbiome research necessitates feedback from across the field, which in turn also supports adoption. We broadly circulated the draft guidelines with the intent to reach researchers around the world; however, we recognize that many research groups and countries are not represented in the Consortium—specifically researchers from Africa and parts of Asia and South America—which currently limits the generalizability. We also emphasize that these guidelines are not meant to be prohibitive to those in less well-resourced areas. We will continue to involve the global microbiome research community in future iterations of the STREAMS guidelines and will continue to expand the STREAMS Consortium. Furthermore, the lead author of the STORMS checklist is a co-author here and a core member of the STREAMS Consortium, and we will continue to work synergistically with the STORMS team on iterations to both sets of guidelines. An ongoing feedback form (https://forms.gle/WgEpBAEAnx3m9o5UA) is publicly available on the STREAMS website for any researcher to provide their input. Updated versions are planned, with new versions being posted publicly on the STREAMS website and via Zenodo22.

We believe the STREAMS guidelines will be valuable for researchers writing manuscripts and can help to streamline the peer review process for both the authors and reviewers. The DMP Tool template guidance will also assist with proper writing, reviewing and reporting on aspects of DMPs for funding agencies and is a machine-actionable implementation of these guidelines. Future efforts include the development of a STREAMS large language model that could be used by researchers to quickly assess microbiome manuscripts. Together, the STREAMS guidelines and accompanying resources will advance the ways in which microbiome research is reported and reviewed, increasing the short- and long-term value of these studies.

Data availability

The guidelines are publicly available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15014818 (ref. 22), on the STREAMS website (https://streamsmicrobiome.org/), and through the DMP Tool site (https://dmptool.org) as the ‘STREAMS Microbiome Guidelines’ template.

References

Alivisatos, A. P. et al. A unified initiative to harness Earth’s microbiomes. Science 350, 507–508 (2015).

Thompson, L. R. et al. A communal catalogue reveals Earth’s multiscale microbial diversity. Nature 551, 457–463 (2017).

Martiny, J. B. H. et al. The emergence of microbiome centres. Nat. Microbiol. 5, 2–3 (2020).

Banerjee, S. & van der Heijden, M. G. A. Soil microbiomes and one health. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 21, 6–20 (2023).

Stulberg, E. et al. An assessment of US microbiome research. Nat. Microbiol. 1, 15015 (2016).

Jansson, J. K. & Baker, E. S. A multi-omic future for microbiome studies. Nat. Microbiol. 1, 16049 (2016).

Wilkinson, M. D. et al. The FAIR Guiding Principles for scientific data management and stewardship. Sci. Data 3, 160018 (2016).

Berg, G. et al. Microbiome definition re-visited: old concepts and new challenges. Microbiome 8, 103 (2020).

Hornung, B. V. H., Zwittink, R. D. & Kuijper, E. J. Issues and current standards of controls in microbiome research. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 95, fiz045 (2019).

Cernava, T. et al. Metadata harmonization–Standards are the key for a better usage of omics data for integrative microbiome analysis. Environ. Microbiome 17, 33 (2022).

Huttenhower, C., Finn, R. D. & McHardy, A. C. Challenges and opportunities in sharing microbiome data and analyses. Nat. Microbiol. 8, 1960–1970 (2023).

Northen, T. R. et al. Community standards and future opportunities for synthetic communities in plant–microbiota research. Nat. Microbiol. 9, 2774–2784 (2024).

Field, D. et al. The Genomic Standards Consortium. PLoS Biol. 9, e1001088 (2011).

Yilmaz, P. et al. Minimum information about a marker gene sequence (MIMARKS) and minimum information about any (x) sequence (MIxS) specifications. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 415–420 (2011).

Eloe-Fadrosh, E. A. et al. A practical approach to using the Genomic Standards Consortium MIxS reporting standard for comparative genomics and metagenomics. Methods Mol. Biol. Clifton NJ 2802, 587–609 (2024).

Parks, D. H. et al. A standardized bacterial taxonomy based on genome phylogeny substantially revises the tree of life. Nat. Biotechnol. 36, 996–1004 (2018).

Roux, S. et al. Minimum Information about an Uncultivated Virus Genome (MIUViG). Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 29–37 (2019).

Mirzayi, C. et al. Reporting guidelines for human microbiome research: the STORMS checklist. Nat. Med. 27, 1885–1892 (2021).

Elm, E. von et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 370, 1453–1457 (2007).

Little, J. et al. STrengthening the REporting of Genetic Association Studies (STREGA)—an extension of the STROBE statement. Genet. Epidemiol. 33, 581–598 (2009).

Kelliher, J. M. et al. Microbiome data management in action workshop: Atlanta, GA, USA, June 12–13, 2024. Environ. Microbiome 20, 40 (2025).

Kelliher, J. & Eloe-Fadrosh, E. STREAMS guidelines. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15014818 (2025).

About. DMP Tool https://dmptool.org/about_us (2025).

Buttigieg, P. L. et al. The Environment Ontology: contextualising biological and biomedical entities. J. Biomed. Semant. 4, 43 (2013).

Carroll, S. R. et al. The CARE principles for indigenous data governance. Data Sci. J. 19, 43–43 (2020).

Glass, E. M. et al. MIxS-BE: a MIxS extension defining a minimum information standard for sequence data from the built environment. ISME J. 8, 1–3 (2014).

Dundore-Arias, J. P. et al. Community-driven metadata standards for agricultural microbiome. Res. Phytobiomes J. 4, 115–121 (2020).

Simpson, A. et al. MISIP: a data standard for the reuse and reproducibility of any stable isotope probing-derived nucleic acid sequence and experiment. GigaScience 13, giae071 (2024).

Katz, K. et al. The Sequence Read Archive: a decade more of explosive growth. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, D387–D390 (2022).

Sumner, L. W. et al. Proposed minimum reporting standards for chemical analysis. Metabolomics 3, 211–221 (2007).

Schymanski, E. L. et al. Identifying small molecules via high resolution mass spectrometry: communicating confidence. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 2097–2098 (2014).

Willis, A. D. & Clausen, D. S. Planning and describing a microbiome data analysis. Nat. Microbiol. 10, 604–607 (2025).

Vujkovic-Cvijin, I. et al. Host variables confound gut microbiota studies of human disease. Nature 587, 448–454 (2020).

Kukutai, T. & Black, A. CARE-ing for Indigenous nonhuman genomic data—rethinking our approach. Science 385, eadr2493 (2024).

Boettiger, C. An introduction to Docker for reproducible research. SIGOPS Oper. Syst. Rev. 49, 71–79 (2015).

Schloss, P. D. Identifying and overcoming threats to reproducibility, replicability, robustness, and generalizability in microbiome research. mBio https://doi.org/10.1128/mbio.00525-18 (2018).

Joos, R. et al. Examining the healthy human microbiome concept. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 23, 192–205 (2025).

Fonseca, A. et al. Investigating antibiotic free feed additives for growth promotion in poultry: effects on performance and microbiota. Poult. Sci. 103, 103604 (2024).

Kellogg, C. A. & Pratte, Z. A. Unexpected diversity of Endozoicomonas in deep-sea corals. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 673, 1–15 (2021).

Berg, M. et al. Host population diversity as a driver of viral infection cycle in wild populations of green sulfur bacteria with long standing virus–host interactions. ISME J. 15, 1569–1584 (2021).

Tláskal, V. et al. Complementary roles of wood-inhabiting fungi and bacteria facilitate deadwood decomposition. mSystems https://doi.org/10.1128/msystems.01078-20 (2021).

Novak, V. et al. Multi-laboratory study establishes reproducible methods for plant-microbiome research in fabricated ecosystems. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.10.02.615924 (2024).

Becsei, A. et al. Time-series sewage metagenomics distinguishes seasonal, human-derived and environmental microbial communities potentially allowing source-attributed surveillance. Nat. Commun. 15, 7551 (2024).

Chen, M. et al. Molecular mechanisms and environmental adaptations of flagellar loss and biofilm growth of Rhodanobacter under environmental stress. ISME J. 18, wrae151 (2024).

Fernandes, V. M. C. et al. Rainfall pulse regime drives biomass and community composition in biological soil crusts. Ecology 103, e3744 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF) under award number 2422717. We thank the American Society for Microbiology for support during the Microbiome Data Management in Action workshop in June 2024, and especially A. Corby and N. Nguyen for their participation. Any opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this presentation are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NSF, NOAA/OAR or the Department of Commerce. Any use of trade, firm or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the US Government. This material is based in part upon work supported by the National Ecological Observatory Network (NEON), a programme sponsored by the NSF and operated under cooperative agreement by Battelle. The work conducted by the National Microbiome Data Collaborative (https://ror.org/05cwx3318) is supported by the Genomic Science Program in the US Department of Energy (DOE), Office of Science and Office of Biological and Environmental Research (BER) under contract numbers DE-AC02-05CH11231 (LBNL), 89233218CNA000001 (LANL) and DE-AC05-76RL01830 (PNNL). This work was supported by the US Geological Survey Coastal and Marine Hazards and Resources Program. This work was supported (in part) by the National Center for Biotechnology Information of the National Library of Medicine (NLM), National Institutes of Health (NIH). The contributions of the NIH author(s) are considered Works of the United States Government. The findings and conclusions presented in this paper are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NIH or the US Department of Health and Human Services. G.B. was supported by a Science Focus Area Grant from the DOE, BER, Biological System Science Division (BSSD) under grant number LANLF59T and the Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center, DOE BER award number DE-SC0018409. J.P.D.A. was supported by the Foundation for Food and Agriculture Research New Innovator in Food and Agriculture Research award number FF-NIA20--0000000056. The work conducted by the US Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute (https://ror.org/04xm1d337), a DOE Office of Science User Facility, is supported by the Office of Science of the DOE operated under contract number DE-AC02-05CH11231. P.B. was supported by MEYS LUC23152. M.S. was supported by NSF award number ABI2149505. Work conducted at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory was supported under the auspices of the US DOE under award SCW1632 and contract DE-AC52-07NA27344. S. Record was supported by Hatch project award number [MEO-022425], from the US Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture. V.R. was supported by NSF Biology Integration Institutes Program award number 2022070. T.N. and V.N. were supported by DOE BER through the Trial Ecosystem Advancement for Microbiome Science (TEAMS) and m-CAFEs Microbial Community Analysis and Functional Evaluation in Soils, a Science Focus Area led by the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory under contract number DE-AC02-05CH11231. L.R.T. was supported by award NA21OAR4320190 to the Northern Gulf Institute from NOAA’s Office of Oceanic and Atmospheric Research, US Department of Commerce (LA-UR-25-22860).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

J.M.K. and E.A.E.-F. wrote the paper with input from all authors. All authors contributed to, read, and approved the final version of the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Microbiology thanks Chris Greening, Thulani Makhalanyane and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Notes 1–3 and description of Supplementary Information.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Kelliher, J.M., Mirzayi, C., Bordenstein, S.R. et al. STREAMS guidelines: standards for technical reporting in environmental and host-associated microbiome studies. Nat Microbiol 10, 3059–3068 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-025-02186-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-025-02186-2

This article is cited by

-

Celebrating 10 years of Nature Microbiology

Nature Microbiology (2026)