Abstract

Understanding the human gut microbiome requires comprehensive genomic catalogues, yet many lack geographic diversity and contain medium-quality metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) missing up to 50% of genomic regions, potentially distorting functional insights. Here we describe an enhanced Human Reference Gut Microbiome (HRGM2) resource, a catalogue of near-complete MAGs (≥90% completeness, ≤5% contamination) and isolate genomes. HRGM2 comprises 155,211 non-redundant near-complete genomes from 4,824 prokaryotic species across 41 countries, representing a 66% increase in genome count and a 50% boost in species diversity compared to the Unified Human Gastrointestinal Genome catalogue. It enabled improved DNA-based species profiling, resolution of strain heterogeneity and survey of the human gut resistome. The exclusive use of these genomes improved metabolic capacity assessment, enabling high-confidence, automated genome-scale metabolic models of the entire microbiota and revealing disease-associated microbial metabolic interactions. This resource will facilitate reliable functional insights into gut microbiomes.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

By accessing the web server, www.decodebiome.org/HRGM2/, users can browse and download all genomes for representative species, their annotations and metadata, including geographical origin, taxonomy, genomic content and genome statistics. The five classes of protein catalogues, 16S rRNA sequences and SNVs are also provided with their functional annotation and taxonomic origin. In addition to publicly available datasets, we incorporated three newly generated datasets (PRJNA1227720, PRJNA1227423 and PRJNA1226738), with basic metadata in Supplementary Table 11 and raw metagenomic sequencing data are available in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive. Metadata for the published datasets and samples used are available in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The source code utilized for the construction and analysis of HRGM2 is publicly available in GitHub at https://github.com/netbiolab/HRGM2 (ref. 97).

References

Kim, N. et al. Genome-resolved metagenomics: a game changer for microbiome medicine. Exp. Mol. Med. 56, 1501–1512 (2024).

Kim, C. Y. et al. Human reference gut microbiome catalog including newly assembled genomes from under-represented Asian metagenomes. Genome Med. 13, 134 (2021).

Almeida, A. et al. A unified catalog of 204,938 reference genomes from the human gut microbiome. Nat. Biotechnol. 39, 105–114 (2021).

Nayfach, S., Shi, Z. J., Seshadri, R., Pollard, K. S. & Kyrpides, N. C. New insights from uncultivated genomes of the global human gut microbiome. Nature 568, 505–510 (2019).

Bowers, R. M. et al. Minimum information about a single amplified genome (MISAG) and a metagenome-assembled genome (MIMAG) of bacteria and archaea. Nat. Biotechnol. 35, 725–731 (2017).

Chaumeil, P. A., Mussig, A. J., Hugenholtz, P. & Parks, D. H. GTDB-Tk: a toolkit to classify genomes with the Genome Taxonomy Database. Bioinformatics 36, 1925–1927 (2019).

Orakov, A. et al. GUNC: detection of chimerism and contamination in prokaryotic genomes. Genome Biol. 22, 178 (2021).

Blanco-Miguez, A. et al. Extending and improving metagenomic taxonomic profiling with uncharacterized species using MetaPhlAn 4. Nat. Biotechnol. 41, 1633–1644 (2023).

Watson, A. R. et al. Metabolic independence drives gut microbial colonization and resilience in health and disease. Genome Biol. 24, 78 (2023).

Heinken, A., Basile, A., Hertel, J., Thinnes, C. & Thiele, I. Genome-scale metabolic modeling of the human microbiome in the era of personalized medicine. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 75, 199–222 (2021).

Poyet, M. et al. A library of human gut bacterial isolates paired with longitudinal multiomics data enables mechanistic microbiome research. Nat. Med. 25, 1442–1452 (2019).

Liu, C. et al. Enlightening the taxonomy darkness of human gut microbiomes with a cultured biobank. Microbiome 9, 119 (2021).

Parks, D. H., Imelfort, M., Skennerton, C. T., Hugenholtz, P. & Tyson, G. W. CheckM: assessing the quality of microbial genomes recovered from isolates, single cells, and metagenomes. Genome Res. 25, 1043–1055 (2015).

Kim, C. Y., Ma, J. & Lee, I. HiFi metagenomic sequencing enables assembly of accurate and complete genomes from human gut microbiota. Nat. Commun. 13, 6367 (2022).

Chklovski, A., Parks, D. H., Woodcroft, B. J. & Tyson, G. W. CheckM2: a rapid, scalable and accurate tool for assessing microbial genome quality using machine learning. Nat. Methods 20, 1203–1212 (2023).

Brown, C. T. et al. Unusual biology across a group comprising more than 15% of domain Bacteria. Nature 523, 208–211 (2015).

Uritskiy, G. V., DiRuggiero, J. & Taylor, J. MetaWRAP—a flexible pipeline for genome-resolved metagenomic data analysis. Microbiome 6, 158 (2018).

Maghini, D. G. et al. Expanding the human gut microbiome atlas of Africa. Nature 638, 718–728 (2025).

Leviatan, S., Shoer, S., Rothschild, D., Gorodetski, M. & Segal, E. An expanded reference map of the human gut microbiome reveals hundreds of previously unknown species. Nat. Commun. 13, 3863 (2022).

Zeng, S. et al. A compendium of 32,277 metagenome-assembled genomes and over 80 million genes from the early-life human gut microbiome. Nat. Commun. 13, 5139 (2022).

Wood, D. E., Lu, J. & Langmead, B. Improved metagenomic analysis with Kraken 2. Genome Biol. 20, 257 (2019).

Lu, J., Breitwieser, F. P., Thielen, P. & Salzberg, S. L. Bracken: estimating species abundance in metagenomics data. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 3, e104 (2017).

Sun, Z. et al. Challenges in benchmarking metagenomic profilers. Nat. Methods 18, 618–626 (2021).

Wright, R. J., Comeau, A. M. & Langille, M. G. I. From defaults to databases: parameter and database choice dramatically impact the performance of metagenomic taxonomic classification tools. Microb. Genom. 9, 000949 (2023).

Yan, Y., Nguyen, L. H., Franzosa, E. A. & Huttenhower, C. Strain-level epidemiology of microbial communities and the human microbiome. Genome Med. 12, 71 (2020).

Shi, Z. J., Nayfach, S. & Pollard, K. S. Maast: genotyping thousands of microbial strains efficiently. Genome Biol. 24, 186 (2023).

Shi, Z. J., Dimitrov, B., Zhao, C., Nayfach, S. & Pollard, K. S. Fast and accurate metagenotyping of the human gut microbiome with GT-Pro. Nat. Biotechnol. 40, 507–516 (2022).

Treangen, T. J., Ondov, B. D., Koren, S. & Phillippy, A. M. The Harvest suite for rapid core-genome alignment and visualization of thousands of intraspecific microbial genomes. Genome Biol. 15, 524 (2014).

Zheng, J. et al. dbCAN3: automated carbohydrate-active enzyme and substrate annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, W115–W121 (2023).

Wardman, J. F., Bains, R. K., Rahfeld, P. & Withers, S. G. Carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZymes) in the gut microbiome. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 20, 542–556 (2022).

Cantalapiedra, C. P., Hernandez-Plaza, A., Letunic, I., Bork, P. & Huerta-Cepas, J. eggNOG-mapper v2: functional annotation, orthology assignments, and domain prediction at the metagenomic scale. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38, 5825–5829 (2021).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Tanabe, M., Sato, Y. & Morishima, K. KEGG: new perspectives on genomes, pathways, diseases and drugs. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, D353–D361 (2017).

Harris, M. A. et al. The Gene Ontology (GO) database and informatics resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, D258–D261 (2004).

Mistry, J. et al. Pfam: the protein families database in 2021. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, D412–D419 (2021).

Lombard, V., Golaconda Ramulu, H., Drula, E., Coutinho, P. M. & Henrissat, B. The carbohydrate-active enzymes database (CAZy) in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D490–D495 (2014).

Galperin, M. Y. et al. COG database update: focus on microbial diversity, model organisms, and widespread pathogens. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, D274–D281 (2021).

Kulmanov, M. & Hoehndorf, R. DeepGOPlus: improved protein function prediction from sequence. Bioinformatics 36, 422–429 (2020).

Ney, L. M. et al. Short chain fatty acids: key regulators of the local and systemic immune response in inflammatory diseases and infections. Open Biol. 13, 230014 (2023).

Bhattacharya, T., Ghosh, T. S. & Mande, S. S. Global profiling of carbohydrate active enzymes in human gut microbiome. PLoS ONE 10, e0142038 (2015).

Ducarmon, Q. R. et al. Large-scale computational analyses of gut microbial CAZyme repertoires enabled by Cayman. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.01.08.574624 (2024).

Alcock, B. P. et al. CARD 2023: expanded curation, support for machine learning, and resistome prediction at the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D690–D699 (2023).

Gaurav, A., Bakht, P., Saini, M., Pandey, S. & Pathania, R. Role of bacterial efflux pumps in antibiotic resistance, virulence, and strategies to discover novel efflux pump inhibitors. Microbiology 169, 001333 (2023).

Hassan, K. A. et al. Pacing across the membrane: the novel PACE family of efflux pumps is widespread in Gram-negative pathogens. Res. Microbiol. 169, 450–454 (2018).

Lokesh, D., Parkesh, R. & Kammara, R. Bifidobacterium adolescentis is intrinsically resistant to antitubercular drugs. Sci. Rep. 8, 11897 (2018).

Tang, B. et al. Characteristics of oral methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis isolated from dental plaque. Int. J. Oral Sci. 12, 15 (2020).

Turner, N. A. et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: an overview of basic and clinical research. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 17, 203–218 (2019).

Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Kawashima, M. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG for taxonomy-based analysis of pathways and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D587–D592 (2023).

Eisenhofer, R., Odriozola, I. & Alberdi, A. Impact of microbial genome completeness on metagenomic functional inference. ISME Commun. 3, 12 (2023).

Fujii, N. et al. Metabolic potential of the superphylum Patescibacteria reconstructed from activated sludge samples from a municipal wastewater treatment plant. Microbes Environ. 37, ME22012 (2022).

Gu, C., Kim, G. B., Kim, W. J., Kim, H. U. & Lee, S. Y. Current status and applications of genome-scale metabolic models. Genome Biol. 20, 121 (2019).

Heinken, A. et al. Genome-scale metabolic reconstruction of 7,302 human microorganisms for personalized medicine. Nat. Biotechnol. 41, 1320–1331 (2023).

Magnusdottir, S. et al. Generation of genome-scale metabolic reconstructions for 773 members of the human gut microbiota. Nat. Biotechnol. 35, 81–89 (2017).

Mendoza, S. N., Olivier, B. G., Molenaar, D. & Teusink, B. A systematic assessment of current genome-scale metabolic reconstruction tools. Genome Biol. 20, 158 (2019).

Zorrilla, F., Buric, F., Patil, K. R. & Zelezniak, A. metaGEM: reconstruction of genome scale metabolic models directly from metagenomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, e126 (2021).

Borer, B. & Magnusdottir, S. The media composition as a crucial element in high-throughput metabolic network reconstruction. Interface Focus 13, 20220070 (2023).

Machado, D., Andrejev, S., Tramontano, M. & Patil, K. R. Fast automated reconstruction of genome-scale metabolic models for microbial species and communities. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, 7542–7553 (2018).

Zelezniak, A. et al. Metabolic dependencies drive species co-occurrence in diverse microbial communities. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 6449–6454 (2015).

Furuichi, M. et al. Commensal consortia decolonize Enterobacteriaceae via ecological control. Nature 633, 878–886 (2024).

Wan, Z. et al. Intermediate role of gut microbiota in vitamin B nutrition and its influences on human health. Front. Nutr. 9, 1031502 (2022).

Bui, T. P. et al. Production of butyrate from lysine and the Amadori product fructoselysine by a human gut commensal. Nat. Commun. 6, 10062 (2015).

Muduli, S., Karmakar, S. & Mishra, S. The coordinated action of the enzymes in the L-lysine biosynthetic pathway and how to inhibit it for antibiotic targets. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 1867, 130320 (2023).

Scribani Rossi, C. et al. Nutrient sensing and biofilm modulation: the example of L-arginine in Pseudomonas. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 4386 (2022).

Arsene-Ploetze, F., Nicoloff, H., Kammerer, B., Martinussen, J. & Bringel, F. Uracil salvage pathway in Lactobacillus plantarum: transcription and genetic studies. J. Bacteriol. 188, 4777–4786 (2006).

Lee, S. & Lee, I. Comprehensive assessment of machine learning methods for diagnosing gastrointestinal diseases through whole metagenome sequencing data. Gut Microbes 16, 2375679 (2024).

Loesche, W. J. & Gibbons, R. J. Amino acid fermentation by Fusobacterium nucleatum. Arch. Oral Biol. 13, 191–202 (1968).

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120 (2014).

Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9, 357–359 (2012).

Nurk, S., Meleshko, D., Korobeynikov, A. & Pevzner, P. A. metaSPAdes: a new versatile metagenomic assembler. Genome Res. 27, 824–834 (2017).

Li, D., Liu, C. M., Luo, R., Sadakane, K. & Lam, T. W. MEGAHIT: an ultra-fast single-node solution for large and complex metagenomics assembly via succinct de Bruijn graph. Bioinformatics 31, 1674–1676 (2015).

Li, H. Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 34, 3094–3100 (2018).

Feng, X., Cheng, H., Portik, D. & Li, H. Metagenome assembly of high-fidelity long reads with hifiasm-meta. Nat. Methods 19, 671–674 (2022).

Danecek, P. et al. Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtools. Gigascience https://doi.org/10.1093/gigascience/giab008 (2021).

Kang, D. D. et al. MetaBAT 2: an adaptive binning algorithm for robust and efficient genome reconstruction from metagenome assemblies. PeerJ 7, e7359 (2019).

Wu, Y. W., Simmons, B. A. & Singer, S. W. MaxBin 2.0: an automated binning algorithm to recover genomes from multiple metagenomic datasets. Bioinformatics 32, 605–607 (2016).

Alneberg, J. et al. Binning metagenomic contigs by coverage and composition. Nat. Methods 11, 1144–1146 (2014).

Parks, D. H. et al. GTDB: an ongoing census of bacterial and archaeal diversity through a phylogenetically consistent, rank normalized and complete genome-based taxonomy. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, D785–D794 (2022).

Ondov, B. D. et al. Mash: fast genome and metagenome distance estimation using MinHash. Genome Biol. 17, 132 (2016).

Olm, M. R., Brown, C. T., Brooks, B. & Banfield, J. F. dRep: a tool for fast and accurate genomic comparisons that enables improved genome recovery from metagenomes through de-replication. ISME J. 11, 2864–2868 (2017).

Saheb Kashaf, S., Almeida, A., Segre, J. A. & Finn, R. D. Recovering prokaryotic genomes from host-associated, short-read shotgun metagenomic sequencing data. Nat. Protoc. 16, 2520–2541 (2021).

Jain, C., Rodriguez, R. L., Phillippy, A. M., Konstantinidis, K. T. & Aluru, S. High throughput ANI analysis of 90 K prokaryotic genomes reveals clear species boundaries. Nat. Commun. 9, 5114 (2018).

Minh, B. Q. et al. IQ-TREE 2: new models and efficient methods for phylogenetic inference in the genomic era. Mol. Biol. Evol. 37, 1530–1534 (2020).

Letunic, I. & Bork, P. Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v5: an online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, W293–W296 (2021).

Seemann, T. barrnap 0.9: rapid ribosomal RNA prediction. GitHub https://github.com/tseemann/barrnap (2018).

Chan, P. P. & Lowe, T. M. tRNAscan-SE: searching for tRNA genes in genomic sequences. Methods Mol. Biol. 1962, 1–14 (2019).

Tonkin-Hill, G. et al. Producing polished prokaryotic pangenomes with the Panaroo pipeline. Genome Biol. 21, 180 (2020).

Seemann, T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 30, 2068–2069 (2014).

Steinegger, M. & Soding, J. Clustering huge protein sequence sets in linear time. Nat. Commun. 9, 2542 (2018).

Steinegger, M. & Soding, J. MMseqs2 enables sensitive protein sequence searching for the analysis of massive data sets. Nat. Biotechnol. 35, 1026–1028 (2017).

Fritz, A. et al. CAMISIM: simulating metagenomes and microbial communities. Microbiome 7, 17 (2019).

Huerta-Cepas, J. et al. eggNOG 5.0: a hierarchical, functionally and phylogenetically annotated orthology resource based on 5090 organisms and 2502 viruses. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D309–D314 (2019).

Suzek, B. E. et al. UniRef clusters: a comprehensive and scalable alternative for improving sequence similarity searches. Bioinformatics 31, 926–932 (2015).

Tesson, F. et al. Systematic and quantitative view of the antiviral arsenal of prokaryotes. Nat. Commun. 13, 2561 (2022).

Zhou, Z. et al. METABOLIC: high-throughput profiling of microbial genomes for functional traits, metabolism, biogeochemistry, and community-scale functional networks. Microbiome 10, 33 (2022).

Machado, D. et al. Polarization of microbial communities between competitive and cooperative metabolism. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 5, 195–203 (2021).

Otasek, D., Morris, J. H., Boucas, J., Pico, A. R. & Demchak, B. Cytoscape Automation: empowering workflow-based network analysis. Genome Biol. 20, 185 (2019).

Ma, S. et al. Population structure discovery in meta-analyzed microbial communities and inflammatory bowel disease using MMUPHin. Genome Biol. 23, 208 (2022).

Ma, J. et al. The source code utilized for the construction and analysis of HRGM2. GitHub https://github.com/netbiolab/HRGM2 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Research Foundation funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (2022M3A9F3016364, 2022R1A2C1092062 to I.L.); by the Technology Innovation Program (20022947) funded by the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy (MOTIE, Korea); and in part by the Brain Korea 21(BK21) FOUR program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.M., N.K. and I.L. conceived the study. J.M. and N.K. constructed the catalogue and performed bioinformatics analysis. J.H.C., W.K. and S.B. contributed to bioinformatics analysis. C.Y.K. provided technical and scientific advice. Y.L., H.S.K., Y.D.H., D.Y. and E.H. contributed sequencing data generated from unpublished studies. S.Y. constructed the web server. I.L. supervised the project. J.M., N.K. and I.L. wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

I.L. is a founder of and shareholder in DECODE BIOME. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Microbiology thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

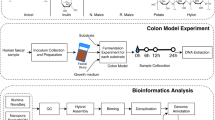

Extended Data Fig. 1 Bioinformatics pipelines for HRGM2 construction.

a, The overall pipeline for HRGM2 construction. b, Pipeline to control genome quality. c, CheckM2 assessment of 10,172 MQ genomes previously assessed by CheckM (completeness-underestimated). The 6,281 genomes that were added to the near-complete (NC) genome set based on assessment using universal bacterial markers and CPR markers are marked with blue dots. The vertical and horizontal dashed lines indicate the 90% completeness and 5% contamination threshold, respectively. The grey area includes genomes that meet the NC genome criteria according to CheckM2. d, Count and proportion of filtered in and out by universal bacterial markers and CPR markers that meet the NC criteria under CheckM2.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Geographic origin of metagenomic samples in UHGG and HRGM2.

The number of metagenomic samples from which the MAGs originate in UHGG and HRGM2 by continent and country.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Extended comparative analyses supporting the HRGM2 overview.

a, Abundance distributions of phyla Elusimicrobiota (up) and Spirochaetota (down) across Africa and non-Africa datasets. All African datasets used for the construction of HRGM2 are included. For comparison, five non-African datasets were randomly selected. The datasets are represented by study accession and country. In the case of “PRJEB39223, United Kingdom”, 400 samples were randomly selected due to the large total sample size. Relative abundances were batch-corrected using MUPPHin and log10-transformed. A phylum was considered present in a sample only if its relative abundance exceeded 1e-06; values below this threshold were replaced with 1e-06. Thus, a y-axis value of -6 indicates absence of the phylum in that sample. Boxes were sorted from left to right, in descending order by median. b, Comparison between HRGM2 and UHGG for the number of NC member genomes for conspecific pairs. c-d, Comparison of the percentage of classified reads between HRGM2 and UHGG at (c) each taxonomic rank and (d) the genus rank, with datasets stratified by continent. A total of 2,624 metagenomic samples not used in either catalog were utilized, and the number of samples included in each dataset is provided in Supplementary Table 6. For boxplots, box lengths represent the interquartile range of the data, and whiskers extend to the lowest and highest values within 1.5 times the interquartile range from the first and third quartiles, respectively. The center bar represents the median. All the outliers are shown in the plots.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Summary of HRGM2 species-specific marker gene database.

a, Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree with annotations of the number of species-specific marker genes. The color of the strip according to the number of species-specific marker genes is the same as in (b, c). b-c, The number and proportion of species in (b) HRGM2 and (c) Collinsella genus according to the number of species-specific marker genes.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Analysis of strain-level heterogeneity across geographic regions in the human gut microbiota.

a, Number of species exceeding varying thresholds of near-complete (NC) genomes required for SNV-based analysis. HRGM2 consistently retains more species than UHGG across all thresholds, demonstrating enhanced capacity to resolve subspecies-level genetic heterogeneity. b, Comparison of the number of SNVs identified in species with ≥10 non-redundant NC genomes present in both catalogs. Boxplots show the distribution of SNV detection ratios (HRGM2/UHGG) per species. The number of species for each phylum is as follows: Campylobacterota, n = 6; Fusobacteriota, n = 5; Methanobacteriota, n = 2; Firmicutes, n = 81; Actinobacteriota, n = 47; Proteobacteria, n = 55; Desulfobacterota, n = 5; Bacteroidota, n = 111; Firmicutes_A, n = 295; Firmicutes_C, n = 36; Thermoplasmatota, n = 2; Spirochaetota, n = 5; Elusimicrobiota, n = 2; Verrucomicrobiota, n = 11. Box lengths represent the interquartile range of the data, and whiskers extend to the lowest and highest values within 1.5 times the interquartile range from the first and third quartiles, respectively. The center bar represents the median. All the outliers are shown in the plot. c, Number of species within each phylum exhibiting subspecies-level geographic stratification between Europe/US and Asia (black bars), based on PERMANOVA test (p-value < 0.01 and pseudo-F statistic > 30). The reported pseudo-F and p-value come from a permutation-based upper-tailed (one-sided) test (default 999 permutations in scikit-bio). d, Representative phylogenetic trees constructed from SNVs identified in metagenomic samples for top 20 species with geographic stratification, colored by geographic origin (green: Asia; red: Europe/US). Species names, HRGM2 species identifiers, and the corresponding pseudo-F statistics are shown below each tree.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Functional landscape of human gut microbiome.

a, Summary of functional prediction pipeline in HRGM2. b, Average copy number of CAZyme families per phylum. GH: Glycoside Hydrolase, GT: Glycosyl Transferase, CE: Carbohydrate Esterase, CBM: Carbohydrate Binding Module, PL: Polysaccharide Lyase, AA: Auxiliary Activity. c, Average copy number of GH CAZyme families for genera with more than 100 GH CAZyme families. d, Explained variance by Western/non-Western categorization for the 10 species with the most distinct CAZyme profiles between Western and non-Western continents. In (c) and (d), the color of the bars represents phylum. e, Comparison of the prevalence and the copy number of each CAZyme family between Faecalibacillus intestinalis genomes from Western and non-Western countries (371 genomes from Western and 417 genomes from non-Western countries). Violin plots display the distribution density, while overlaid box plots denote the median (center line), interquartile range (25th-75th percentiles; box bounds), and the minimum and maximum values (whiskers).

Extended Data Fig. 7 Summary of genome qualities for UHGG.

a, Number and proportion of genomes with completeness ≥ 90% and contamination ≤ 5% (left pie chart), that passed GUNC (center pie chart), and that met the NC criteria (right pie chart), in UHGG representative genomes (up) and non-redundant genomes (down). b, Distribution of the percentage of genomes that are not completeness ≥ 90% and contamination ≤ 5% (top), that did not pass GUNC (middle), and that did not meet the NC criteria (bottom) for each UHGG species with at least two non-redundant genomes. The distributions are either categorized by the number of non-redundant genomes included in each species (left) or not (right) (2 ≤ # < 10, n = 1,590; 10 ≤ # < 100, n = 877; ≥ 100, n = 319; Total, n = 2,786). Box lengths represent the interquartile range of the data, and whiskers extend to the lowest and highest values within 1.5 times the interquartile range from the first and third quartiles, respectively. The center bar represents the median. All the outliers are shown in the plots.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Additional analyses for metabolic independence and interaction.

a, Possession percentage of 33 KEGG modules for UHGG (n = 4,644) and HRGM2 (n = 4,824) species. Statistical significance was assessed using a two-sided Mann-Whitney U test (P = 1.74e-42), indicating notable differences in module possession between the two catalogs. b, HMI and LMI species percentage in UHGG and HRGM2. c, d, Representative genome size (c) and the number of countries where each species originated (d) of HMI, other, LMI species. In (c) and (d), the number of HMI/Others/LMI species is 751/3,685/388 and 688/3,533/383, respectively; (d) considers only species with country information. P-value was calculated using a two-sided Mann-Whitney U test (P for HMI-Others/Others-LMI/HMI-LMI = (c) 3.270e-227/1.198e-205/2.297e-168; (d) 6.308e-29/1.839e-05/3.472e-05). e, Number and percentage of species with available isolate genomes, categorized by metabolic independence. The association between metabolic independence and the availability of isolate genomes was assessed by a Chi-squared test (two-sided). f, Comparison of the proportions of non-overlapping metabolites (left), reactions (middle), and gene-associated reactions (right) between 327 conspecific MQ and NC GEMs. Differences were evaluated with two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test (P for Metabolite/Reaction/Gene-associated reaction = 3.078e-19/1.203e-26/9.691e-45). g, Violin plot showing distribution of MIP and MRO scores for F18-mix (n = 18) and F13-mix (n = 13) strains of Kp-2H7. P-value was calculated using a one-sided Mann-Whitney U test. For boxplots in Extended Data Fig. 8, box lengths represent the interquartile range of the data, and whiskers extend to the lowest and highest values within 1.5 times the interquartile range from the first and third quartiles, respectively. The center bar represents the median. All the outliers are shown in the plots. ****, P < 1e-04; ns: not significant, P > 0.05.

Supplementary information

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 5

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 6

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 5

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 6

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 7

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 8

Statistical source data.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Ma, J., Kim, N., Cha, J.H. et al. A human gut metagenome-assembled genome catalogue spanning 41 countries supports genome-scale metabolic models. Nat Microbiol 11, 317–334 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-025-02206-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-025-02206-1