Abstract

Unwanted side reactions occurring at electrode|electrolyte interfaces significantly impact the cycling life of lithium metal batteries. However, a comprehensive view that rationalizes these interfacial reactions and assesses them both qualitatively and quantitatively is not yet established. Here, by combining multiple analytical techniques, we systematically investigate the interfacial reactions in lithium metal batteries containing ether-based non-aqueous electrolyte solutions. We quantitatively monitor various nanoscale-driven processes such as the reduction and oxidation pathways of lithium salt and organic solvents, the formation of various solid-electrolyte interphase species, the gas generation within the cell and the cross-talk processes between the electrodes. We demonstrate that the consumption of lithium ions owing to the continuous decomposition of the lithium bis(fluorosulfonyl)imide salt, which dominates the interfacial reactions, results in ion depletion during the cell discharge and battery failure. On the basis of these findings, we propose an electrolyte formulation in which lithium bis(fluorosulfonyl)imide content is maximized without compromising dynamic viscosity and bulk ionic conductivity, aiming for long-cycling battery performance. Following this strategy, we assemble and test Li (20 μm thickness)||LiNi0.8Mn0.1Co0.1O2 (17.1 mg cm−2 of active material) single-layer stack pouch cells in lean electrolyte conditions (that is, 2.1 g Ah−1), which can effectively sustain 483 charge (0.2 C or 28 mA)/discharge (1 C or 140 mA) cycles at 25 °C demonstrating a discharge capacity retention of about 77%.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Lithium (Li) metal batteries (LMBs) are among the most promising high-energy battery chemistries that could enable long-range electric vehicles and electric aviation1,2,3. Various companies, such as SES AI4, Sion Power5 and Cuberg (a subsidiary of Northvolt)6, are actively pursuing the development of LMBs. However, current LMB performance does not meet commercialization requirements, and technology-based innovations are urgently needed. Research on non-aqueous liquid electrolytes is of high interest7 owing to straightforward implementation in a standard Li-ion cell manufacturing line8. Electrolyte designs such as (localized) high-concentration electrolytes ((L)HCEs)9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17 and weakly solvating electrolytes18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25 demonstrate high anodic stability and operational compatibility with high-potential positive electrodes such as LiNi0.8Mn0.1Co0.1O2 (NMC811). They also promote the formation of inorganic, anion-derived solid-electrolyte interphases (SEIs) that enable Li cycling coulombic efficiency (CE) of the cells with Li-free working electrodes and Li counter electrodes (for example, Li||Cu cells) over 99.5% (refs. 8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25). Loss of Li inventory (LLI) owing to the formation of electronically isolated ‘dead’ metallic Li could be minimized with rationally designed electrolytes to improve the CE of LMBs26. However, state-of-the-art LMBs still exhibit considerable LLI dominated by continuous SEI formation, which requires further suppression.

The function and evolution of SEIs in LMBs are different from those in Li-ion batteries with graphite-based negative electrodes. Graphite particles enable the formation of compact SEIs (cSEIs) that maintain their structural integrity during prolonged cell cycling (Fig. 1a). By contrast, because of the significant volume changes during Li stripping/plating, cSEIs on the surface of Li metal continuously rupture and form (Fig. 1b), leading to the accumulation of residual SEIs27 (rSEIs; Fig. 1c,d). As a result, a graphite||NMC811 cell demonstrates a capacity decay slowdown during long-term cycling28, while a Cu||NMC811 cell demonstrates a sharp capacity decay owing to a constant rate of LLI (Fig. 1e). Therefore, electrolyte development for Li-ion batteries focuses mostly on additives that decompose to form surface-passivating SEIs29,30. By contrast, ideal non-aqueous electrolytes for LMBs should exhibit high cathodic stability to minimize cSEI formation and sufficient availability of SEI-forming components to sustain SEI formation during long-term cell cycling. Such designs require an understanding of the electrolyte-consuming interfacial reactions. Here we present a systematic study of electrode|electrolyte interfacial reactions to inform rational electrolyte design. Evolutions of electrolyte consumption and LLI during LMB cycling, as well as their interfacial reaction pathways, were quantitatively mapped out. We demonstrate that the Li-ion depletion during discharge, originating from the lithium bis(fluorosulfonyl)imide (LiFSI) decomposition, is the main contributor to capacity fading of the LMB. We also develop and test a tailored electrolyte formulation containing a low-molecular-weight diluent and a high LiFSI weight percentage, which enables the effective long-term cycling of Li||NMC811 single-layer stack (SLS) pouch cells in lean electrolyte conditions.

a,b, Schematics of SEI evolution on graphite (the grey colour represents graphite and the earth yellow colour represents lithiated graphite) (a) and Li metal (the dark grey colour represents Li metal and the orange colour represents Cu current collector) (b). c,d, A digital photo (c) and a cross-section SEM image (d) of the rSEIs on a cycled Li metal electrode (the sample was obtained from a 50 μm Li||NMC811 SLS pouch cell with LiFSI–1.2DME–3TTE under 0.2–1 C at the EOL). e, Cycling performances of a graphite||NMC811 cell and a Cu||NMC811 cell using LiFSI–1.2DME–3TTE as the electrolyte. f, Schematic representation of the design of the experiment used to quantitatively analyse the interfacial reactions in Cu||NMC811 SLS pouch cells. g, The experimental procedure of T-DEMS to quantify ‘dead’ Li, LiH, Li2CO3 and other decomposition products and E-G&IC to quantify the remaining LiFSI and organic solvents in the Cu||NMC811 cells after cycling.

Assembly, testing, characterization and analysis of Cu||NMC811 pouch cells

Cu||NMC811 SLS pouch cells were assembled (Methods), each with 0.3 g of LHCE-type, non-aqueous electrolyte solution containing LiFSI, dimethoxyethane (DME) and 1,1,2,2-tetrafluoroethyl-2,2,3,3-tetrafluoropropyl ether (TTE) with a molar ratio of 1:1.2:3 (LiFSI–1.2DME–3TTE). In each cell, NMC811 can provide a Li capacity equivalent of ~156 mAh (that is, ‘active Li’) in the charging process (Fig. 1f). We define ‘active Li’ as the electrochemically active Li inventory in both the positive and negative electrodes readily available for battery cell charge and discharge, excluding Li in the electrolyte. After cycling, titration-differential electrochemical mass spectrometry (T-DEMS; Methods, Supplementary Notes 1 and 2, and Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2) and extraction-gas and ion chromatography (E-G⁣ Methods, Supplementary Note 3, Supplementary Figs. 2–8 and Supplementary Table 1) measurements were carried out to quantify the consumption of active Li, LiFSI and organic solvents (Fig. 1g). T-DEMS was also implemented with different titrants to quantify the LiH and Li2CO3 accumulated on the negative electrode. Combining these methodologies with physicochemical characterizations and simulations, we quantify the electrolyte-soluble by-products, gases and electrode interphases generated through interfacial reactions and reveal the corresponding formation pathways.

Figure 2a shows the distribution of Li capacity at different cycles, in which the contributions were determined and calculated using T-DEMS and equation (1). The grey dashed line shows that the discharge capacity of the Cu||NMC811 cells gradually decreases after remaining relatively stable for 20 cycles (0.2 C (28 mA) charge/1 C (140 mA) discharge cycling). This was due to the Li reservoir created on the surface of the Cu electrode after the first cycle replenishing the LLI31 (Fig. 2b,c). The deep discharge capacity (see Methods for the definition) initially decreases and then increases (Fig. 2b), indicating active Li consumption at the negative electrode and an aggravation in the Li stripping kinetics. The active Li loss, represented in equivalent capacity of Li, that resulted in ‘dead’ Li, LiH and Li2CO3 formation is determined via T-DEMS (Fig. 2c), and the capacity in the rSEI formed (CrSEI, including LiH and Li2CO3) was calculated as follows, with the assumption that all LLI are from rSEIs and ‘dead’ Li:

a, A diagram of Li capacity distribution at different cycles of Cu||NMC811 cells measured through deep discharge and T-DEMS (Methods, Supplementary Notes 1 and 2, and Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2). b–d, Evolutions of the deep discharge capacity (b), the equivalent capacity of Li in ‘dead’ Li (c) and the equivalent capacity of Li in rSEIs (d). These results were extracted from a and redrawn. The formation of LiH and Li2CO3 on the negative electrode was also quantified (d). e,f, Evolutions of the masses of LiFSI, DME (e) and TTE (f) in the electrolyte during the cycling of Cu||NMC811 cells measured through E-G&IC (Methods, Supplementary Note 3, Supplementary Figs. 2–8 and Supplementary Table 1). g, Molar consumption rates of LiFSI and DME, in relation to the molar accumulation rate of elemental Li in the rSEIs. The data were calculated based on the results in a–f. Each data point in a–g represents the average of four replicate samples, and the error bars indicate the standard errors. h–j, C 1s (h), F 1s (i) and S 2p (j) XPS spectra of the rSEIs formed on the negative electrode of a Cu||NMC811 SLS pouch cell after 100 cycles under 0.2–1 C between 2.8 V and 4.3 V at 25 °C. k,l, Elemental composition ratio of the negative electrode of a Cu||NMC811 SLS pouch cell after 100 cycles under 0.2–1 C between 2.8 V and 4.3 V at 25 °C obtained using two methods: calculated from active Li and electrolyte quantification results (k) and quantified through direct ICP-OES measurement (l), respectively. In this figure, we assumed the losses of active Li and electrolyte components are completely transferred into either rSEIs or ‘dead’ Li.

CrSEI represents the equivalent capacity of Li in the rSEIs. C1st charge is the charging capacity of the first cycle. Clast cycle @ 1C discharge is the discharging capacity under 1 C rate at the last cycle, Cdeep discharge is the capacity during the deep discharging process after the last cycle, and CLi in ‘dead’ Li is the equivalent capacity of Li in ‘dead’ Li (see Methods for definition and calculation process), as quantified by T-DEMS. We also assume that all electrolyte decomposition products are accumulated into rSEIs. These assumptions are rationalized in subsequent sections. Figure 2b–d shows that active Li at the negative electrode is mostly consumed through the formation of rSEIs instead of ‘dead’ Li. LiH and Li2CO3 species in the rSEIs were detected via Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR; Supplementary Fig. 9), cryogenic transmission electron microscopy (cryo-TEM; Supplementary Fig. 10), cryogenic scanning transmission electron microscopy (cryo-STEM; Supplementary Fig. 10) and electron-energy-loss spectroscopy (EELS; Supplementary Fig. 10). Note that LiH and Li2CO3 account for only a small portion of the equivalent capacity of Li in the rSEIs (Fig. 2d).

Electrolyte consumption is quantified through E-G&IC. After 100 cycles, nearly 60% of LiFSI mass is irreversibly lost (Fig. 2e), while the mass of DME only decreases by about 16%. These results suggest that the LiFSI salt is the main participant in electrode|electrolyte interfacial reactions, resulting in a significant accumulation of salt-derived inorganic species in the rSEIs. Interestingly, the TTE mass remains constant during prolonged cell cycling (Fig. 2f), in contrast to previous literature reports17,32,33. From ab initio simulations, the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital for three DME molecules coordinated with one Li+ ion (−0.59 eV) is lower than that of a TTE molecule (−0.34 eV), which does not participate in the solvation of the salt-derived Li+ ions16 (Supplementary Fig. 11). When both DME and FSI− coordinate with one Li+ ion, the FSI− anion further decreases the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital. Analysis of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of the solvation environments under an applied electric field shows that TTE abundance at the interface is lower than in the bulk, while the FSI− abundance is relatively uniform (Supplementary Fig. 12 and Supplementary Table 2). These simulation results rationalize the E-G&IC results, in which the main decrease in electrolyte content was attributed to FSI−, with essentially no loss in TTE. Therefore, fluorinated diluents such as TTE promote efficient cell cycling (that is, high CE) by means of their electrochemical inactivity and ability to minimize interfacial side reactions, and not their tendency to form desired chemical species in the SEI.

Shown in Fig. 2g are the consumption rates of LiFSI (1.6 μmol per cycle) and DME (0.3 μmol per cycle), along with the accumulation rate of Li from the positive electrode in the rSEIs (12.5 μmol per cycle). These rates were calculated by first converting the amounts of each species (capacity or mass) from Fig. 2d,e into molar amounts (mmol) and then plotting the molar amounts against cycle number, followed by a linear regression to obtain the slopes (molar consumption/accumulation rates). We compare the rates of electrolyte consumption and Li accumulation in the rSEI to explore the stoichiometric relationships of the reactions. Taking into consideration the balanced equation for the complete decomposition of LiFSI into LiF, Li3N, Li2S and Li2O (Li compounds observed in the rSEI based on the X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) results):

it can be seen that 16 additional moles of Li-ions are necessary to fully decompose 1 mol of LiFSI, leading to a theoretical 16:1 ratio of moles of active Li consumed to moles of LiFSI consumed. This 16:1 ratio is twice as high as the experimental ratio of the accumulation rate of Li in the rSEI to the consumption rate of LiFSI (12.5:1.6 μmol per cycle = 7.8:1) for cells cycled 100 times. The lower experimental ratio indicates that LiFSI was not completely reduced after 100 cycles, and its reduction intermediates exist in the rSEIs.

XPS analyses of the rSEIs corroborate these results. In the C 1s spectrum (Fig. 2h), the presence of signals indicative of C–O and C=O bonds accounts for the moderate decomposition of the DME solvent. Signals associated with C–F bonds are absent, aligning with the quantification result that TTE remains stable during cycling. In the F 1s and S 2p spectra (Fig. 2i,j), not only signals corresponding to LiF and Li2S, but also those accounting for F–S bonds, S6+ and S4+ are observed. This further verifies the incomplete reduction of LiFSI and the existence of its decomposition intermediates in the rSEIs. XPS on the cSEIs was also performed (Supplementary Note 4 and Supplementary Fig. 13), providing additional evidence to support these findings.

An elemental mapping could be performed for the compounds (consisting of rSEIs and ‘dead’ Li) on the negative electrode after 100 cycles. The amount (mmol) of each element was totalled from the amount of active Li loss detected using T-DEMS and the amount of LiFSI and DME decomposition detected using E-G&IC. The mass of each element was computed using its atomic mass, and the resulting masses were further normalized by the mass of Li, yielding a ‘standardized mass ratio’ of 1:0.86 for Li:S (Fig. 2k). This ratio is compared with that obtained from a direct inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES; Fig. 2l) measurement on a negative electrode sample after 100 cycles. Elemental weight-per-weight percentages of Li and S measured by ICP-OES were normalized by the value for Li to give a standardized mass ratio of 1:0.82, which is in good agreement with the T-DEMS and E-G&IC-derived ratio of 1:0.86. This verifies that the T-DEMS and E-G&IC approaches present high reliability in quantifying the reactants participating in the interfacial reactions during cycling, and their resulting products.

Overall, LiFSI decomposition is the main cause of LLI. Its reduction—though not complete—involves the consumption of a considerable number of additional Li-ions. Recently developed LiFSI-based electrolytes that enabled anion-derived SEIs have contributed to CE enhancements in Li||Cu cells8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25, but the associated active Li consumption still limits the CE to ~99.5–99.8% (refs. 21,22,23,24). Our results indicate that CE is likely bottlenecked for these LiFSI-based electrolytes unless the Li deposition morphology can be fundamentally altered, and/or the cSEI can maintain its integrity during cycling to avoid rupture.

In Supplementary Fig. 14a, the formation of an ~3-nm-thick rock-salt layer at the surface of the positive electrode active material after 10 cycles (Cu||NMC811, 0.2–1 C, 25 °C) was observed via ex situ high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM). Since this layer is very thin, active site loss at the cathode side should be minimal, and Li-ions should be able to freely traverse the cathode. Indeed, capacity loss owing to NMC811 active site loss was observed to be negligible (Li||NMC811; Supplementary Fig. 14b) and the observed capacity loss (owing instead to dynamic polarization) is reversible and can be recovered by introducing a ‘depolarization protocol’, slowly charging at 0.05 C (7 mA) and then discharging at 0.05 C 10 times (with 5 min rest intervals) every 50 cycles. These results also confirmed the anodic stability of the ether-based LHCE. Electrolyte loss to gas production and other dissolved and interfacial products was also assessed. In situ DEMS for a Cu||NMC811 cell showed no gas generation other than a minimal amount of H2 during cycling (Supplementary Fig. 14c,d). Analysis of the gas chromatography (GC), ion chromatography (IC), 19F and 1H NMR measurements (Supplementary Fig. 14e–h) confirms the absence of side products dissolved in the electrolyte after 100 cycles between 2.8 V and 4.3 V (25 °C). These results support our assumption that the consumption of active Li and electrolyte consumption goes towards either rSEIs or ‘dead’ Li. It should be noted that the small amount of H2 (303 nmol) generated during the first charge originates from the reduction of trace water (Supplementary Notes 5 and 6, Supplementary Figs. 14c and 15–18, and Supplementary Tables 3–5). Simulations show that the final reduction product of water, with an H2 intermediate, is LiH (Supplementary Fig. 19); therefore, it contributes to the LiH accumulation in the rSEIs. Other sources of LiH will be analysed and discussed later.

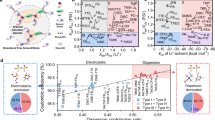

We also mapped out the interfacial reactions in Cu||NMC811 cells using ab initio simulations (Fig. 3a). TTE was considered electrochemically stable according to the E-G&IC results (Fig. 2f). Reduction of the FSI− anion, the dominant interfacial reaction pathway, was first studied (Fig. 3b). The reduction of DME in the electrolyte solution is considered as the main process to favour the formation of LiH (Fig. 3c). Also, considering the presence of Li2CO3 in the rSEIs (Fig. 2d), which is unlikely to form through the reduction of an ether solvent, we explored the possible oxidation pathways of DME (Fig. 3d) and the cross-talk of their products between the positive electrode and negative electrode.

a, A schematic of interfacial reaction pathways in LMBs with LiFSI–1.2DME–3TTE as the electrolyte. b–d, Free energy diagrams of the pathways of LiFSI reduction (b), DME reduction (c) and DME oxidation (d). TM stands for transition metal. \(\Delta {G}^{\ddagger }\) represents the reaction activation energy. e, Cycling performances of a Cu||NMC811 and a 50 μm Li||NMC811 SLS pouch cells (under 0.2–1 C at 25 °C and between 2.8 V and 4.3 V). f,g, Consumption of DME, LiFSI (f) and TTE (g) during the cycling of Cu||NMC811 and 50 μm Li||NMC811 SLS pouch cells (under 0.2–1 C at 25 °C and between 2.8 V and 4.3 V). Each data point represents the average of four replicate samples, and the error bars indicate the standard errors. h, Molar concentrations, dynamic viscosities and bulk ionic conductivities of the electrolyte formulations at different cycles of 50 μm Li||NMC811 SLS pouch cells (Methods and Supplementary Note 8). i, Cycling performances of fresh 50 μm Li||NMC811 cells with LHCEs with lower Li salt molar concentrations. j, Simulated discharge potential profiles of a 50 μm Li||NMC811 SLS pouch cell at different cycles. k, Simulated electrolyte concentration distributions within a 50 μm Li||NMC811 SLS pouch cell at different cycles. Molar concentration and bulk ionic conductivity data of the electrolyte were extracted from h for the simulation.

The reduction of the FSI− anion leads to the formation of inorganic Li compounds, including LiF, Li2O, Li3N and Li2S (Fig. 3b). The first two defluorination steps show minimal activation energies (0.06 eV and 0.00 eV), contributing to the fast decomposition of the FSI− anion. The occurrence of subsequent steps requires overcoming higher activation energies (0.49 eV and 0.47 eV), resulting in slower kinetics. Therefore, some intermediate species remain in the rSEIs, in alignment with the S6+ and S4+ species observed in the XPS results (Fig. 2j) and the incomplete FSI− anion decomposition implied by Fig. 2g. The essence of FSI− anion reduction is the gradual decrease in the oxidation state of sulfur (from 6+ to 2–), with compensation from active Li that causes LLI.

The reduction of DME initiates with C–O bond breaking, forming −OLi and −CLi compounds (Fig. 3c). The −CLi compound could further decompose into LiH and methyl vinyl ether, which could further polymerize. Since the energies were simulated for a gas–solid chemical reaction and did not consider the surrounding electrolyte environment or interfacial electric field, they reasonably possess deviations from values under experimental conditions. As a result, although the second step seems thermodynamically unfavourable, it is still the most predictable route among various LiH formation pathways simulated. Owing to the relatively high activation energy (0.62 eV) of the initial step of reduction, DME decomposed moderately compared with the FSI− anion so the accumulation of LiH in the rSEIs is low.

The oxidation of DME initiates with the breaking of a C–H bond (Fig. 3d). The hydrogen and carbon radicals then bond to surface oxygen atoms. The electron on hydrogen transfers to surface oxygen and adjacent transition metal atoms. Further C–H bond breaking leads to the formation of a C=O bond. When this happens, the oxygen atom is cleaved from the NMC811 lattice and incorporated into a newly formed formate molecule (Fig. 3d). Moderate surface oxygen loss causes lattice distortion, and its accumulation could ultimately lead to the collapse of layered structures and the formation of rock-salt phases (Supplementary Fig. 14a). Further oxidation could lead to the generation of CO2, whose cross-talk from the positive to the negative electrode likely accounted for the formation of Li2CO3 in the rSEIs (Fig. 3a) through the following chemical equation:

Quantified footprints of Li2CO3 and LiH formation are provided in Supplementary Figs. 20 and 21 and discussed in Supplementary Note 7. Although the native Li2CO3 layer on the surface of NMC811-based electrodes partially oxidizes to CO2 and contributes to the Li2CO3 accumulation on the negative electrode, the CO2 generated during DME oxidation and its cross-talk from the positive electrode to the negative electrode is the dominating contributor (Supplementary Fig. 21a). Meanwhile, the reduction of DME accounts for the LiH accumulation in the rSEIs (Supplementary Fig. 21b). Nevertheless, the overall LLI during the formation of Li2CO3 and LiH is minor compared with other interfacial reactions, especially the reduction of the FSI− anion. These results align with the continuous yet moderate consumption of DME (Fig. 2e).

Assembly, testing, characterization and analysis of Li||NMC811 pouch cells

After the qualitative and quantitative mapping of the interfacial reactions in Cu||NMC811 SLS pouch cells, we apply this acquired knowledge to investigate the failure mechanism occurring in Li||NMC811 SLS pouch cells. Using a 50 μm Li foil instead of a Cu foil as the negative electrode prolongs the cycle life, but it is still limited to 300 cycles (Fig. 3e). Also, in this case, electrolyte quantification shows that the decomposition of FSI− anions is dominant while the amount of TTE remains stable (Fig. 3f,g). As a result, LiFSI molar concentration continuously decreases during cycling (Fig. 3h and Supplementary Note 8). Measuring electrolyte formulations at different cycles in Fig. 3f,g, we found that the dynamic viscosity continuously decreases, while the bulk ionic conductivity reaches a maximum at 0.79 M after 200 cycles and subsequently decreases (Methods and Fig. 3h). To rule out long-term degradation of the Li metal electrode as the cause of cell failure, we sampled the electrolyte solution (that is, 0.28LiFSI–0.92DME–3TTE) from a Li||NMC811 SLS pouch cell that underwent 300 cycles and injected it in an uncycled 50 μm Li||NMC811 SLS pouch cell. As shown in Fig. 3i, this cell reached failure within 30 cycles.

Previous reports proposed that the decay of an anion-dominant solvation environment led to unstable SEIs and cell failure34. The formulation at cycle 300 (that is, 0.28LiFSI–0.92DME–3TTE) shows a 1:3.3 LiFSI-to-DME molar ratio (Supplementary Table 6). However, a 2 M LiFSI/DME electrolyte solution, compared with 0.28LiFSI–0.92DME–3TTE, despite possessing a lower LiFSI-to-DME molar ratio, a less anion-participating Li-ion solvation35, less anion-derived SEIs and a lower CE, enables a longer life for 50 μm Li||NMC811 SLS cells (Supplementary Note 9, Supplementary Figs. 22–27 and Supplementary Tables 6 and 7). This rules out the changes in the Li-ion solvation environment as the direct cause of the cell failure. However, when the overall LiFSI concentration is diminished while maintaining a fixed LiFSI-to-DME ratio, the failure of the 50 μm Li||NMC811 cells occurs more rapidly (Fig. 3i). This feature correlates the cell failure with the inadequate Li+ and FSI− concentrations and ion depletion during cycling. To better understand this aspect, we carried out electrochemical simulations (Methods and Supplementary Fig. 28). Simulated discharge capacity remains stable before 150 cycles and then decays in later cycles (Fig. 3j), aligning with experimental data (Fig. 3e). Li-ion concentration across the cell during discharge was further mapped out (Fig. 3k). At cycle 200, Li-ions start to deplete in proximity of the current collector of the porous NMC811-based positive electrode. As the cycle number increases, the depleted region expands, decreasing the NMC811 contribution to the cell capacity (Fig. 3e,j). The impact of rSEI accumulation on the ion depletion phenomenon is further analysed in Supplementary Note 10 and Supplementary Figs. 29 and 30. This failure mechanism for Li metal cells with an LHCE suggests that the Li-ion concentration in the electrolyte, continuously decreasing owing to LiFSI decomposition, must always be maintained above a certain level (dependent on Li-ion diffusivity, separator and positive electrode thicknesses, and so on) to support stable cycling.

Considering this aspect, we then iterated electrolyte formulations to prolong the cell’s cycle life under practical designs. A critical feature is the balance between the Li metal negative electrode thickness and the non-aqueous electrolyte solution amount, which we systematically investigated (Supplementary Table 8). The increase of the Li metal negative electrode thickness effectively prolonged cycle life (Fig. 4a). Almost 600 charge/discharge cell cycles are achieved using a 20-μm-thick Li metal electrode. The lifetime CE (see Methods for definition and calculation process) also increased from ~99.64% in Cu||NMC811 (that is, where the initial Li metal thickness is 0 μm) to ~99.86% in Li||NMC811 cells (Fig. 4b). This result aligns well with the alleviated consumption of the electrolyte components in Li||NMC811 cells during cycling (Fig. 3f,g). We speculate that these features suggest a decrease in the interfacial reaction rates in Li||NMC811 cells, possibly associated with the formation of low surface area electrodeposited metallic Li when Li metal is the substrate instead of Cu. However, this assumption will require further data validation in a future study. A larger electrolyte amount also prolonged the cell’s cycle life. For example, 650 charge/discharge cycles could be achieved using 0.7 g (5 g Ah−1) of electrolyte solution in a 50 μm Li||NMC811 SLS pouch cell (Fig. 4c,d).

a, Cycle life of LMBs with various Li metal electrode thicknesses. Triangular symbols show the total discharge capacity of cells at the last cycle after deep discharge (the deep discharge refers to the repeated discharging to 2.8 V using successively smaller currents to fully strip the active Li; Methods), which indicates the total amount of active Li remaining on the negative electrode at the EOL. b, Lifetime Li cycling CE results of LMBs in a. Each data point represents the average of twoa to three replicate samples, as shown in a, and the error bars indicate the standard errors. c, Cycle life of 50 μm Li||NMC811 cells with different amounts of injected electrolyte solution. Cycle numbers when the discharge capacity retentions (from the 1st discharge cycle) reach 80% are considered to define the EOL of the cell. d, Cycle life versus amount of injected electrolyte solution according to the data in c. e, Testing of various electrolyte formulations in 20 μm Li||NMC811 SLS pouch cells. All dynamic viscosity and ionic conductivity values were measured at 25 °C. The electrolyte iteration enabled a 20 μm Li||NMC811 SLS pouch cell to achieve nearly 500 cycles with 2.1 g Ah−1 of electrolyte. Capacity fluctuation of LiFSI–1.2DME–2.75BZ originated from unexpected temperature changes in the testing environment (the standard testing temperature is 25 °C, and unexpectedly reached up to 35 °C). f, A comparison of the lifetime CE (see Methods for detailed calculation) among the electrolytes in e measured using Cu||NMC811 cells. The arrows in each plot in f are used to indicate a specific sample and are not related to the cycle number in the x axis. aData were acquired for only two replicate samples for the 5 μm and 10 μm Li conditions. Three samples were prepared, but one of the samples became damaged owing to unexpected conditions during cycling.

For the assembly of a practical LMB, it is ideal to have the electrolyte below 2.5 g Ah−1 and the Li negative electrode thickness below 20 μm (ref. 36). To achieve long life under these constraints, the electrolyte is the limiting factor. Indeed, the use of a 20-μm-thick Li negative electrode is enough to deliver almost 600 charge/discharge cycles (Fig. 4a), but a large and impractical amount of electrolyte solution, that is, 0.5 g (3.6 g Ah−1) (Fig. 4c), is required. However, considering the knowledge acquired through the measurements and analyses described above, we used an application-driven design of the electrolyte, initially halving the amount of TTE, resulting in a LiFSI–1.2DME–1.5TTE electrolyte solution. With 2.1 g Ah−1 of this electrolyte formulation, the 20 μm Li||NMC811 SLS pouch cell cycle life increased from ~270 to ~350 cycles (Fig. 4e). However, this increase in cell life did not match with the weight % increase of LiFSI in the electrolyte (from 19 wt% to 29 wt%). This behaviour is associated with the increase of the electrolyte’s dynamic viscosity (Fig. 4e), from 5.2 mPa s to 8.9 mPa s, which hinders the wetting of porous electrode structures such as the rSEIs, thus favouring cell failure before fully utilizing the LiFSI in the electrolyte solution. Therefore, an increase in the LiFSI concentration in the electrolyte should not be done at the expense of the electrolyte’s dynamic viscosity and bulk ionic conductivity. This aspect is essential, but not trivial to implement. In our case, to realize this, the TTE diluent needs to be replaced. By screening prior state-of-the-art formulations, we found that bis(2,2,2-trifluoroethyl)ether (BTFE) was reported as a low-molecular-weight diluent able to decrease the dynamic viscosity37. As a result, a LiFSI–1.2DME–3BTFE electrolyte solution containing 22 wt% of LiFSI demonstrated a bulk ionic conductivity of 4.1 mS cm−1 and a dynamic viscosity of 3.3 mPa s (both measured at 25 °C). The 20 μm Li|LiFSI–1.2DME–3BTFE|NMC811 SLS pouch cell can be cycled for almost 500 cycles before reaching the end of life (EOL), defined as 80% capacity retention. This cycling performance corresponds to a projected specific energy value of 389 Wh kg−1 for a 50 Ah pouch cell with the same cell design (Supplementary Table 9). After the SLS pouch cell failure (that is, delivery of 0 mAh of discharge capacity), LiFSI–1.2DME–3BTFE electrolyte solution was refilled into the cell, which restarted cycling and recovered a discharge capacity of about 0.11 Ah (Supplementary Fig. 31). LiFSI–1.2DME–3BTFE was also tested in 50 μm Li||NMC811 SLS pouch cell configuration with 3.6 g Ah−1 electrolyte loading. This cell delivers almost 900 charge/discharge cycles before reaching the EOL (Supplementary Fig. 32). Additional measurements and analyses are carried out to demonstrate that LiFSI–1.2DME–3BTFE electrolyte follows the same decomposition mechanism as LiFSI–1.2DME–3TTE electrolyte and the improved cell’s cycle life is mainly associated with the wt% increase of the LiFSI salt in the electrolyte formulation (Supplementary Note 11 and Supplementary Fig. 33).

To prove the applicability of our application-driven design of the electrolyte, we also tested benzene (BZ) as a diluent38. BZ is neither a fluorinated nor an ether molecule. However, like BTFE, it possesses low molecular weight and dynamic viscosity (0.604 mPa s, 25 °C)39. As a result, a LiFSI–1.2DME–2.75BZ electrolyte solution containing 37 wt% of LiFSI demonstrates a bulk ionic conductivity of 4.1 mS cm−1 and a viscosity of 4.7 mPa s (both measured at 25 °C). The LiFSI–1.2DME–2.75BZ electrolyte formulation enables ~450 cycles under 2.1 g Ah−1 in 20 μm Li||NMC811 SLS pouch cell configuration (Fig. 4e). However, Fig. 4f shows that none of the proposed electrolyte formulations enable high lifetime CEs in Li metal cells. This supports the assumption that electrolyte decomposition, rather than LLI, is the limiting factor affecting the cycle life of the 20 μm Li||NMC811 cells. It also indicates that electrolyte durability (number of cycles that can be sustained with a certain amount of electrolyte) could vary significantly under a similar CE. Thus, the electrolyte formulation needs to be optimized to guarantee long cell life on the basis of an adequate Li-ion solvation environment (Supplementary Note 12, Supplementary Fig. 34 and Supplementary Table 10).

Conclusion and outlook

The proposed application-driven electrolyte design strategy effectively prolonged LMB cycle life under practical conditions, but further innovations aimed at improving the reversibility of Li metal during cell cycling are still needed. To formulate non-aqueous electrolyte solutions, which are electrochemically stable towards Li metal, the electrolyte components need to possess high cathodic stability and weak solvation energy to suppress electrolyte degradation at the negative electrode. Previous efforts following this strategy showed limited success because only the solvents were being tuned40. The key issue lies in the reductive behaviour of the salt-derived components. Indeed, salt anions with high cathodic stability need to be designed and tested. Another viable approach is to design more electro-chemo-mechanically robust cSEIs that remain intact during cycling such that rSEI formation is suppressed. To achieve this, electrolyte decomposition products must form interphases that are strong and ductile enough to accommodate the volume variation during the Li stripping/plating process. The design and implementation of Li-hosting materials41 with predefined interfaces and structures are possible solutions, although mechanical integrity and scalability are critical aspects.

Methods

Preparation of the electrolyte solutions and SLS pouch cells

LiFSI (99.99%, Kaixin), DME (99.95%, Guotai), TTE (99.5%, Aladdin), BTFE (99%, Aladdin) and BZ (99.9%, Aladdin) were used for the preparation of electrolyte solutions. All chemicals were used as received and the water content was determined to be <20 ppm by Karl Fischer titration. All solutions were gravimetrically prepared and magnetically stirred in glass scintillation vials in a dry room (4 m × 5 m) with relative humidity <1% at 25 °C using Pasteur pipets (for liquids) and a 4-digit analytical balance. Graphite||NMC811, Cu||NMC811 and Li||NMC811 SLS pouch cells were fabricated in a CATL pilot line (technical specifications of the electrode formulations cannot be disclosed as they are covered by an industrial non-disclosure agreement) and used for cycling after electrolyte injection. NMC811-based positive electrodes are 42 mm × 49.5 mm and double-side coated, with an active material loading of 17.1 mg cm−2 and an areal capacity of 3.53 mAh cm−2 for a 0.2 C (28 mA) current on each side. Cell assembly was performed in the same dry room mentioned above. Electrolyte injection was done gravimetrically after sealing three sides of the pouch cell; the final side was heat-sealed under vacuum (−90 kPa) immediately thereafter. Parameters for the pouch cell are shown in Supplementary Table 8. All the cells were set at 0.21 MPa (30 psi) initial pressure and cycled under a fixed-gap condition (that is, securing the pouch cell between two aluminium plates with an initial 0.21 MPa pressure using four screws, such that the clamped cell maintains a fixed thickness) using a Neware CT-4008Tn-5V6A-S1 testing system in a temperature-controlled room set to 25 °C. All cells were cycled at 0.2 C (28 mA)–1 C (140 mA) between 2.8 V and 4.3 V without any prior formation cycles, and the charging followed a constant current–constant potential (CC–CP) protocol with a cut-off current of 0.1 C (14 mA). For simplicity, we abbreviate this cycling process as ‘0.2–1 C’.

T-DEMS

Preparation of cycled electrode samples

The Cu||NMC811 pouch cells were first cycled for 1 cycle, 20 cycles, 40 cycles, 60 cycles, 80 cycles and 100 cycles under 0.2–1 C. A deep discharge procedure was then applied on each cycled Cu||NMC811 pouch cell. The deep discharge procedure refers to the repeated discharging of the cell to 2.8 V using successively smaller currents (7 mA, 3.5 mA and 1 mA) to fully strip the active Li from the negative electrode such that it will not be mistaken as ‘dead’ Li. The deep discharge procedure usually extracts an additional 5–20 mAh of discharge capacity. After deep discharge, the cell was disassembled in an argon-filled glove box (H2O <0.1 ppm, O2 <0.1 ppm). Either the Cu electrode or the NMC811-based electrode was then placed into a titration vessel for subsequent tests (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Quantification of ‘dead’ Li, LiH and Li2CO3

The quantification of ‘dead’ Li and LiH was performed with deuterated ethanol (CD3CD2OD) as the titrant. The quantification of Li2CO3 was performed with 10 M H2SO4 as the titrant. The titration was performed in an in-house developed Teflon container. The gas generated was collected and measured using a differential electrochemical mass spectrometry system (DEMS, Shanghai LingLu Instruments; Supplementary Fig. 1).

Determination of calibration equations

To construct the calibration equations (equations (7) and (8)) used to quantify ‘dead’ Li, Li metal with different known masses was placed into a titration vessel connected to DEMS. After the argon (99.999%, Fuzhou Zhongming Qiti) inflow stabilized, ethanol-d6 (CD3CD2OD, 99%, Aladdin) was injected into the vessel, and the generated gas was flushed into DEMS for analysis. Multiple-ion mode was used to record the ion current of mass/charge ratios: m/z = 3 for hydrogen deuteride (HD) and m/z = 4 for deuterium (D2) gas. Afterwards, calibration equations were obtained through linear regressions of the areas of HD and D2 signals against the Li metal masses (with the origin included; Supplementary Fig. 2a,b). Similarly, calibration equations of LiH were obtained through CD3CD2OD titration on LiH (97%, Macklin) samples (Supplementary Fig. 2c,d).

The reactions of CD3CD2OD with Li metal and LiH happen as follows:

However, weak yet observable signals of HD and D2 were detected for Li metal and LiH, respectively. We attribute this to the non-ideal deuterium abundance in the CD3CD2OD titrant and the random recombination of hydrogen and deuterium radicals during the titration experiments. For the accuracy of subsequent quantifications, we performed linear regressions on both HD and D2 signals for Li metal and LiH (Supplementary Fig. 2a–d).

A calibration equation of Li2CO3 (equation (9)) was obtained through 10 M H2SO4 titration on Li2CO3 (99.5%, Macklin) samples with CO2 as the generated gas42 (Supplementary Fig. 2e).

The reaction of 10 M H2SO4 with Li2CO3 happens as follows:

Quantification of ‘dead’ Li, LiH and Li2CO3 on a sample

To quantify ‘dead’ Li and LiH, a cycled Cu electrode sample was placed into a titration vessel connected to DEMS. After the argon inflow stabilized, CD3CD2OD was injected into the vessel, and the generated gas was flushed into DEMS for measurements. The masses of ‘dead’ Li and LiH on the cycled electrode were set as x and y, respectively, and the areas of peaks attributed to HD and D2 from the DEMS result was set to be A and B, respectively. The values of x and y were determined through the following equations:

To quantify Li2CO3, a similar process was applied with 10 M H2SO4 as the titrant. The mass of Li2CO3 on the sample was set to be z, and the area of the peak attributed to CO2 from the DEMS result was set to be C. The value of z was determined through the following equation:

Here \({k}_{\mathrm{HD}-{\mathrm{Li}}\; {\rm{metal}}}\), \({k}_{\mathrm{HD}-\mathrm{LiH}}\), \({k}_{\mathrm{D}_{2}-{\mathrm{Li}}\; {\rm{metal}}}\), \({k}_{\mathrm{D}_{2}-\mathrm{LiH}}\) and \({k}_{{\mathrm{CO}}_{2}}\) are the slopes of the calibration curves (Supplementary Fig. 2a–e).

In this work, we further standardized the masses of ‘dead’ Li, LiH and Li2CO3 into equivalent Li capacities (CLi) through the following calculations:

In equations (11) and (12), the masses of LiH and Li2CO3 (y and z, respectively) are converted into mole-equivalent masses of Li through their corresponding molar masses. These, along with the mass of ‘dead’ Li (x) in equation (10), are then converted into equivalent Li capacity using the specific capacity of Li (3,860 mAh g−1).

E-G&IC

E-G&IC was performed on Cu||NMC811 and 50 μm Li||NMC811 cells with 0.3 g of electrolyte after cycling for a fixed number of cycles (for example, 1 cycle, 50 cycles, 100 cycles, …, 300 cycles for 50 μm Li||NMC811 cells) under 0.2–1 C.

Preparation of the extraction agent

1,2-Diethoxyethane (DEE, 99.9%, Aladdin, <20 ppm H2O) was used as the internal standard. Diethylene glycol dimethyl ether (diglyme, 99.9%, Aladdin, <20 ppm H2O) was used as the extracting solvent. An extraction agent was prepared by mixing 4 g of DEE with diglyme in a 200 ml volumetric flask at 25 °C in a dry room. The extraction agent was then sealed with parafilm in a scintillation vial and stored under the same conditions for later use.

Extraction of electrolytes in LMBs

Inside an argon-filled glove box (H2O <0.1 ppm, O2 <0.1 ppm), an incision was made at the edge of a cycled LMB pouch cell, through which 5 ml of the extraction agent was injected. The cell was then re-sealed by heat-sealing the pouch along the cut edge. The contents of the sealed cell were thoroughly mixed by first allowing the liquid to diffuse during storage at 25 °C for 3.5 days and then vertically inverting and storing the cell for another 3.5 days. After 7 days, the liquid mixture contained in the pouch cell was extracted via a syringe and syringe-filtered (0.22 μm) for subsequent measurements.

IC and quantification of LiFSI

Determination of calibration equation

LiFSI (20 mg, 40 mg, 60 mg, 80 mg and 100 mg) was dissolved in 1,000 ml of deionized H2O (18.5 MΩ cm at 25 °C, Milli-Q IQ 7000) to form five standard solutions. Each standard solution (5 ml) was measured with IC (Dionex Aquion RFIC, Thermo Scientific) and the area of peaks attributed to the FSI− anion was calculated. Afterwards, a linear regression was performed between the peak area and the LiFSI concentration, serving as the calibration equation (equation (13) and Supplementary Fig. 2f).

Quantification of LiFSI

The extracted liquid of a cycled LMB cell was diluted 200-fold with deionized H2O. The diluted solution (5 ml) was measured with IC. The concentration of LiFSI in the diluted solution was set to be cLiFSI, and the area of the FSI− anion peak from the IC result was set to be SLiFSI. The value of cLiFSI was determined applying the following equation:

Here \({k}_{\mathrm{LiFSI}}\) is the slope of the calibration curve (Supplementary Fig. 2f). The absolute mass of residual LiFSI in the cycled cell mLiFSI was further calculated as follows:

where 200 is the dilution factor and 5.25 ml comes from 5 ml of extraction agent and 0.25 ml from 0.3 g of the electrolyte used in this work.

GC and quantification of DME and TTE

Determination of response factors

The freshly prepared (uncycled) electrolyte (0.3 g) was mixed into 5 ml of extraction agent. The mixture was further diluted fivefold with diglyme to obtain a standard solution. The standard solution (1.5 ml) was measured with GC (Nexis GC-2030, Shimadzu). The masses of DME, TTE and DEE in the standard solution were known (mDME = 32.7 mg, mTTE = 210.6 mg and mDEE = 100.0 mg). The areas of peaks attributed to DME, TTE and DEE were collected from the GC results (SDME, STTE and SDEE). The response factors for DME (fDME) and TTE (fTTE) were calculated as follows:

Quantification of DME and TTE

The extracted liquid of a cycled LMB cell was diluted fivefold with diglyme. The diluted solution (1.5 ml) was measured with GC. The areas of peaks attributed to DME, TTE and DEE were collected from the GC results (SDME-exp, STTE-exp and SDEE-exp). The absolute masses of residual DME (mDME-exp) and TTE (mTTE-exp) in the cycled cell were calculated as follows:

Additional physicochemical characterizations

NMR measurements were carried out using a Bruker AVANCE NEO 500 MHz digital FT-NMR spectrometer. After Cu||NMC811 was cycled under 0.2–1 C for 100 cycles, 5 ml of diglyme was added into the cell. The cell was sealed and stored for 7 days at 25 °C, and then the mixture of cycled electrolyte and diglyme was extracted for the NMR test. The whole sampling procedure was conducted in a dry room.

Electrolyte solutions for Raman measurements were prepared in a dry room and sealed in glass scintillation vials for transfer to a separate laboratory for sample loading. The liquid sample was drawn via capillary action by submerging one end of a quartz capillary tube into the liquid sample under atmospheric conditions. The two ends of the capillary were then sealed with ultra-light clay to prevent sample evaporation and contamination. The sealed capillary was then loaded into a Renishaw InVia Qontor Raman spectrometer. Spectra were acquired at 25 °C using an excitation wavelength of 785 nm.

For dynamic viscosity and ionic conductivity measurements, electrolyte solutions were prepared in a dry room and sealed in glass scintillation vials for transfer to a separate laboratory for measurements. Dynamic viscosities were measured with a Brookfield DV2T viscometer using the SC4-18 spindle at 25 °C under ambient atmospheric conditions. After levelling and autozeroing the equipment, an 8 ml aliquot of the solution (enough liquid to fully submerge the spindle) was transferred to the instrument sample holder and equilibrated at 25 °C for 10 min. Measurements were conducted with periodic stirring. Ionic conductivities were measured with a Shanghai Leici DDSJ-318 conductivity meter at 25 °C under ambient atmospheric conditions. An ~10 ml aliquot of the solution was transferred to and sealed in a 50 ml Falcon tube, and then equilibrated at 25 °C for 10 min in a water bath. The calibration of the meter was verified using low and high ionic conductivity standard samples. The probe head was cleaned with ethanol and DI water in between uses.

XPS measurements were carried out using a Shimadzu Axis Supra+ imaging X-ray photoelectron spectrometer. An Al Kα X-ray (1,486.7 eV) was used as the excitation source, and the data were collected in an area of 700 × 300 µm by using a hemispherical electron energy analyser at an emission power of 195 W. Sputtering was performed on a 3 × 3 cm region with a 5 keV argon ion source and an incident angle of 45°. The electrode samples were washed with DME solvent and dried inside an Ar glove box, and then transferred within an airtight vessel from the glove box to the XPS sample chamber. The sputtering time increments were 0 s, 60 s, 120 s, 180 s and 300 s.

For the ICP-OES measurement, a Cu||NMC811 cell was cycled under 0.2–1 C for 100 cycles, followed by a deep discharge process. Afterwards, the cell was disassembled inside an argon-filled glove box (H2O <0.1 ppm, O2 <0.1 ppm). The solid rSEI formed on the Cu electrodes was collected using a scraper into a glass vial. The collected powder was then soaked in DME for 60–120 min. After removing the supernatant, the powder sample was dried in a vacuum chamber at 25 °C. The soaking and drying procedure was repeated five times in dry room before the sample was measured with a ThermoFisher iCAP PRO ICP-OES. These preparation procedures ensured full removal of active Li and residual electrolyte components from the sample.

For FT-IR measurements, the FT-IR spectra for the cycled Cu electrode were collected with a Thermo Scientific Nicolet iS50 spectrometer. A Cu||NMC811 cell with LiFSI–1.2DME–3TTE was cycled under 0.2–1 C for 100 cycles and deep discharged (deep discharge refers to the repeated discharging of the cell to 2.8 V using successively smaller currents (7 mA, 3.5 mA and 1 mA) to fully strip the active Li from the negative electrode such that it will not be mistaken as ‘dead’ Li). Afterwards, the cell was disassembled within an argon-filled glove box (H2O <0.1 ppm, O2 <0.1 ppm). The Cu electrode was sealed with tape to prevent corrosion in ambient air and was transferred immediately for FT-IR measurement.

For the in situ DEMS measurement of gas generation at 25 °C, an airtight electrochemical vessel was used to accommodate a pouch cell. The electrodes of the pouch cell were connected to two binding posts on the electrochemical vessel so that the cell could be cycled. The edge of the pouch cell was incised before being sealed into the vessel. The vessel was connected to a carrier gas system, and the gas generated from the pouch cell was directed into a mass spectrometer for quantitative analysis. The carrier gas system consisted of a carrier gas (Ar, 99.999%, Fuzhou Zhongming Qiti), a 2.0 μm filter (Swagelok), a digital mass flowmeter (Bronkhorst, EL-FLOW Select) and an in-house developed cold trap with a temperature controller. The Ar gas, regulated by a pressure regulator (set to 0.1 MPa), was directed sequentially through a 2.0 μm filter, a quantitative ring in the pulse inlet system, and the cold trap before entering the mass spectrometer for gas analysis. The filter serves to protect the mass flow controller and the mass spectrometer from small particles in the metal tubing and the sample itself. The flow rate of Ar was maintained at 0.6 ml min−1 to ensure high sensitivity for trace gas analysis inside the pouch cell. The cold trap temperature was set to −90 °C to capture the volatile organic species contained in the carrier gas to protect the mass spectrometer and increase sensitivity.

Scanning electron microscope (SEM) images were captured using a ThermoFisher Helios G4 CX dual-beam focused ion beam (FIB)–SEM and ZEISS GeminiSEM 360. Cross-sectional samples were prepared by cutting a small piece of the sample of interest and polishing with a Hitachi ArBlade 5000 under cryogenic conditions in an argon atmosphere. Samples were transferred in an air-free sample holder.

All the STEM characterizations were performed using an aberration-corrected FEI Themis Z electron microscope equipped with a Gatan GIF Quantum 1065 for EELS operated at 300 kV. For STEM HAADF imaging on the NMC811-based positive electrode, site-specific TEM lamellae were prepared by FIB. The Helios FIB–SEM was used for trenching, in situ lift-out and thinning. To reduce the potential surface damage caused by FIB milling, a further low-energy cleaning at 2 kV was performed. HAADF imaging was then carried out with a convergence angle of 26.5 mrad and an angular collection angle between 60 mrad and 120 mrad. For cryo-TEM, STEM, EDS and EELS characterizations on the rSEI sample, a pure Cu TEM grid was mounted on the Cu negative electrode of a Cu||NMC811 pouch cell, which was cycled under 0.2–1 C. The cell was deep discharged after 10 cycles, and then dissembled inside an argon-filled glove box. The TEM grid was transferred to the microscope using a Fischione 2550 Cryo Transfer Holder. The TEM, STEM, EDS and EELS experiments were performed under a temperature of −170 °C. The probe current used for EELS mapping is ~30 pA, and the dose rate is around 7.5 × 104 e/(Å2 s).

CO2 solubility was measured with an Initial Energy Science and Technology (IEST) GVM2200 in situ cell volume analyser. For the gas solubility test, 10 g of LiFSI–1.2DME–3TTE electrolyte was vacuum sealed in an empty pouch in a dry room. CO2 gas (40 ml) was injected into the electrolyte-containing pouch with a syringe, and the pouch was sealed again with duct tape. The shrinkage of the pouch due to the CO2 dissolved in the electrolyte solution was measured with the in situ cell volume analyser. The pouch was submerged in silicone oil (at 25 °C), and volume changes were measured in real time by applying the Archimedes principle43.

According to the Archimedes principle, when an object is partially or fully submerged in a fluid, it experiences an upward buoyant force equal to the weight of the fluid displaced by the object.

The volume of the cell could be obtained as follows:

where V is the volume of the cell, \(\Delta m\) is the mass of water displaced by the cell, \(\rho\) is the density of water at 25 °C and \(g\) is the gravitational acceleration.

First-principles simulations

All surface calculations were conducted utilizing the density functional theory (DFT) as implemented in the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP)44,45. The electron exchange-correlation energies were determined using the generalized gradient approximation and Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof functional within the DFT framework46. Transition metals were treated using the DFT + U augmented approach with U values of 4 eV, 4.4 eV and 5 eV for Mn, Co and Ni, respectively. The DFT + D3 method, which incorporated dispersion correction, was used to account for weak interactions in the systems under investigation47. All calculations were spin-polarized, and a plane-wave cut-off energy of 520 eV was utilized. All surface calculations were performed using a 2 × 2 × 1 k-point within the Monkhorst–Pack scheme, and a 15 Å vacuum layer was added to avoid the interactions between repeated periodic slabs. A five-layer slab of the (110) surface of Li was utilized to investigate the reduction decomposition process, while the charged NCM811 slab, by taking the Li atoms out, was used to study the DME oxidation process. Geometric structure optimizations were performed until the force on all atoms was less than 0.02 eV Å−1, with energy convergence criteria set to be smaller than 10−5 eV per atom. The climbing image nudged elastic band48 and dimer methods49 were combined to locate the transition states along the reaction pathways, with all transition states verified to have only one imaginary vibrational frequency along the reaction coordinate.

The energies of the highest occupied molecular orbital and lowest unoccupied molecular orbital were calculated using the DFT method at the B3LYP/6-311G+(d, p) level50 implemented in the Gaussian 09 (ref. 51) software package. The SMD (solvation model based on density)52 was chosen to account for the solvent effect.

The conductor-like screening model for real solvents (COSMO-RS) method53,54 was used to get macroscopic gas solubility data. The BP functional and TZVP basis set from the Turbomole programme55 were used for COSMO calculations. The resulting COSMO files were subsequently imported in the COSMOtherm programme56 to determine the solubility of gas57.

MD simulation

MD simulations were carried out with large-scale atomic/molecular massively parallel simulator (LAMMPS)58. As visualized with OVITO59 (Supplementary Fig. 12a), the simulation box encompasses two Li metal electrodes separated by a distance of 144 Å and a region of electrolyte. Each Li metal electrode surface is represented by the (100) facet and has a dimension of 37 Å × 37 Å × 10 Å with 500 atoms. About 130 LiFSI, 157 DME and 472 TTE molecules were placed between the two electrodes, and the configuration was obtained through a preliminary MD simulation of the bulk electrolyte under the NPT ensemble at 298 K.

The OPLS-AA force field60 was used to treat the interactions between the atoms in the liquid phase. Force field parameters were generated by the LigParGen web server61. Parameters for Li in the electrode were obtained from Nichol et al.62. Interactions between electrode and electrolyte atoms were modelled by the Lennard-Jones potentials based on geometric mixing rules, in addition to the long-range Coulomb forces. Electrode atoms were fixed during the simulation, and only electrolyte atoms were allowed to move within the space confined by the two electrodes. Under the NVT ensemble, the system was simulated using the Nosé–Hoover thermostat63 at 313 K.

To accurately depict the charges held by the electrode atoms, we implemented a constant potential method64,65,66,67. This involved dynamically assigning a charge to each electrode atom in a way that ensured that all atoms in one electrode were at a single Poisson potential, while all atoms in the other electrode were at a different Poisson potential. The two potentials were then set to differ by a predetermined value, ΔU. The two electrodes bore charges of equivalent magnitude but opposite signs, resulting in a charge-neutral system overall. On the basis of the constant potential method, the charge held by each atom in the electrodes can be determined through the following equation67:

where Q is a vector containing the charge for each electrode atom, A is the elastance matrix representing the interactions between electrode atoms, b is an electrolyte vector representing the electrostatic potential caused by the electrolyte atoms, which is a function of the electrolyte atom positions67, and v is a vector containing the applied potential (U) for each electrode atom, which depends on ΔU. In this study, one pair of ΔU were used: {−5 V, 5 V}. This corresponds to {bottom electrode potential, top electrode potential} in Supplementary Fig. 12.

The simulation was run for a minimum of 20 ns with a step of 1 fs to allow for equilibration of the solvation structure near the electrode interface. During this time, the initially uncharged electrode gradually acquired charge, and ions with opposite charges approached the electrode to form electric double layers. Following the equilibrium period, samples were taken at 2,000 fs intervals for the final 5 ns, then averaged and analysed. To obtain the distribution of electrolyte species, the space occupied by the electrolyte was segmented into bins with widths of 0.1 Å. Numbers of electrolyte species in each bin were tallied and number densities (Supplementary Fig. 12b) were calculated, which could also be normalized by the corresponding volume density (Supplementary Table 2).

Faradic currents between the electrodes and (electro)chemical reactions were not allowed to happen during this simulation.

Electrochemical simulation

Li||NMC811 cell’s discharge potential profiles (Fig. 3j) and electrolyte concentration distributions (Fig. 3k) were simulated through COMSOL Multiphysics version 6.0. A Li metal electrode was treated as an ideal planar electrode and its surface morphology change during discharging was not considered. Therefore, x = 0 in Fig. 3k represents the interface between Li metal electrode and separator. Parameters of the simulation are listed as follows.

Electrolyte

Diffusion coefficient is 1 × 10−10 m2 s−1. The transference number is 0.363. Static molar concentration and ionic conductivity are extracted from Fig. 3h.

Separator

The thickness is 15 μm. The porosity is 0.39. Tortuosity is correlated with porosity following the Bruggeman relationship68 with a Bruggeman coefficient of 2.

NMC811 positive electrode

The thickness is 49.6 μm. The porosity is 0.25. Tortuosity is correlated with porosity following the Bruggeman relationship with a Bruggeman coefficient of 2.2. The open circuit potential is experimentally measured for a Li||NMC811 cell (Supplementary Fig. 28). The solid-state diffusion coefficient is 4 × 10−15 m2 s−1. The electrochemical reaction rate constant is 8 × 10−12 m s−1.

Li metal negative electrode

The electrochemical reaction rate constant is 6 × 10−11 m s−1.

Calculation of lifetime CE for LMBs

Determination of the overall CE during the cycle life of an LMB (hereinto referred to as lifetime CE) was modified based on our previously reported approach31. After a Cu||NMC811 or Li||NMC811 cell capacity retention decayed to 50–80%, the cell was stopped from cycling and a deep discharge was performed to strip away all the remaining active Li on the negative electrode. We define the ith cycle charge capacity as Ci-c, the last cycle number as nEOL, the total discharge capacity of the last cycle, including that during the deep discharge as CEOL-dc, and the Li capacity of the pristine Li foil as CLi foil (for a Cu||NMC811 cell, CLi foil = 0 mAh). The lifetime Li metal CE is given by

Note that two key experimental operations are necessary:

-

1.

The electrolyte amount needs to be excessive.

This guarantees that the cell failure is due to active Li loss instead of electrolyte consumption.

-

2.

Deep discharge needs to be performed at the last cycle.

Although capacity trends could differ between replicate cells, CEOL-dc results remained consistent (Fig. 4a). This indicated the high repeatability of CE and the impact of rSEIs on Li stripping polarization increase, which led to the discharge capacity variation between replicate cells, especially near EOL. In fact, CEOL-dc results increased along with Li foil thicknesses and cycle life (Fig. 4a). This was because a thicker layer of rSEIs accumulates after longer cycling, leading to a higher polarization during Li stripping. Nevertheless, CEOL-dc is still lower than C1-c for all the cells in Fig. 4a. This guarantees the complete stripping of all active Li on the negative electrode and the accuracy of the CE calculations.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Tarascon, J. M. & Armand, M. Issues and challenges facing rechargeable lithium batteries. Nature 414, 359–367 (2001).

Lin, D., Liu, Y. & Cui, Y. Reviving the lithium metal anode for high-energy batteries. Nat. Nanotechnol. 12, 194–206 (2017).

Albertus, P., Babinec, S., Litzelman, S. & Newman, A. Status and challenges in enabling the lithium metal electrode for high-energy and low-cost rechargeable batteries. Nat. Energy 3, 16–21 (2018).

SES 50Ah Li-metal Cell Data Report (SES AI, 2022); https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/6704ef99f6a4ff8b5b7218b1/671b6665eee268960e2e8ec4_SES-50Ah-Li-Metal-Cell-Data-Report.pdf

Meng, Y. S. Sion Power Lithium Metal Battery Technology Assessment Report (Sion Power, 2022); https://sionpower.com/files/Shirley-Meng-Report-Sion-Power.pdf

Cuberg Lithium Metal Cell Technology (Cuberg, 2022); https://www.datocms-assets.com/38709/1658475133-cuberg-cell-validation-july-2022.pdf

Zhang, J.-G., Xu, W., Xiao, J., Cao, X. & Liu, J. Lithium metal anodes with nonaqueous electrolytes. Chem. Rev. 120, 13312–13348 (2020).

Frith, J. T., Lacey, M. J. & Ulissi, U. A non-academic perspective on the future of lithium-based batteries. Nat. Commun. 14, 420 (2023).

Qian, J. et al. High rate and stable cycling of lithium metal anode. Nat. Commun. 6, 6362 (2015).

Fan, X. et al. Highly fluorinated interphases enable high-voltage Li-metal batteries. Chem 4, 174–185 (2018).

Suo, L. et al. Fluorine-donating electrolytes enable highly reversible 5-V-class Li metal batteries. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 1156–1161 (2018).

Chen, Y. et al. Steric effect tuned ion solvation enabling stable cycling of high-voltage lithium metal battery. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 18703–18713 (2021).

Chen, S. et al. High-voltage lithium-metal batteries enabled by localized high-concentration electrolytes. Adv. Mater. 30, e1706102 (2018).

Chen, S. et al. High-efficiency lithium metal batteries with fire-retardant electrolytes. Joule 2, 1548–1558 (2018).

Ren, X. et al. Localized high-concentration sulfone electrolytes for high-efficiency lithium-metal batteries. Chem 4, 1877–1892 (2018).

Ren, X. et al. Enabling high-voltage lithium-metal batteries under practical conditions. Joule 3, 1662–1676 (2019).

Cao, X. et al. Monolithic solid-electrolyte interphases formed in fluorinated orthoformate-based electrolytes minimize Li depletion and pulverization. Nat. Energy 4, 796–805 (2019).

Yu, Z. et al. Molecular design for electrolyte solvents enabling energy-dense and long-cycling lithium metal batteries. Nat. Energy 5, 526–533 (2020).

Wang, H. et al. Dual-solvent Li-ion solvation enables high-performance Li-metal batteries. Adv. Mater. 33, e2008619 (2021).

Xue, W. et al. FSI-inspired solvent and “full fluorosulfonyl” electrolyte for 4 V class lithium-metal batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 13, 212–220 (2020).

Huang, Y. et al. Eco-friendly electrolytes via a robust bond design for high-energy Li metal batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 15, 4349–4361 (2022).

Sun, C. et al. High-voltage Li metal batteries enabled by adsorption-defluorination mechanism. ACS Energy Lett. 8, 4119–4128 (2023).

Park, E. et al. Exploiting the steric effect and low dielectric constant of 1,2-dimethoxypropane for 4.3 V lithium metal batteries. ACS Energy Lett. 8, 179–188 (2023).

Liao, Y. et al. Eco-friendly tetrahydropyran enables weakly solvating “4S” electrolytes for lithium-metal batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2301477 (2023).

Hou, W.-H. et al. Fluorinated carbamate-based electrolyte enables anion-dominated solid electrolyte interphase for highly reversible Li metal anode. ACS Nano 17, 17527–17535 (2023).

Fang, C. et al. Quantifying inactive lithium in lithium metal batteries. Nature 572, 511–515 (2019).

Wang, H. et al. Efficient lithium metal cycling over a wide range of pressures from an anion-derived solid-electrolyte interphase framework. ACS Energy Lett. 6, 816–825 (2021).

Harlow, J. E. et al. A wide range of testing results on an excellent lithium-ion cell chemistry to be used as benchmarks for new battery technologies. J. Electrochem. Soc. 166, A3031–A3044 (2019).

Song, W. et al. A systematic study of electrolyte additive in single crystal and bimodal LiNi0.8Mn0.1Co0.1O2/graphite pouch cells. J. Electrochem. Soc. 168, 090503 (2021).

Xu, K. Electrolytes and interphases in Li-ion batteries and beyond. Chem. Rev. 114, 11503–11618 (2014).

Wang, H. et al. Rate-dependent failure mechanisms and mitigating strategies of anode-free lithium metal batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 12967–12975 (2023).

Kim, H.-T. et al. Borate-pyran lean electrolyte-based Li-metal batteries with minimal Li corrosion. Nat. Energy 9, 57–69 (2024).

Xie, J. et al. Fluorobenzene-based diluted highly concentrated carbonate electrolyte for practical high-voltage lithium metal batteries. J. Power Sources 506, 230086 (2021).

Zhou, M.-Y. et al. Quantifying the apparent electron transfer number of electrolyte decomposition reactions in anode-free batteries. Joule 6, 2122–2137 (2022).

Ding, J.-F. et al. Non-solvating and low-dielectricity cosolvent for anion-derived solid electrolyte interphases in lithium metal batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 11442–11447 (2021).

Niu, C. et al. High-energy lithium metal pouch cells with limited anode swelling and long stable cycles. Nat. Energy 4, 551–559 (2019).

Chen, S. et al. High-voltage lithium-metal batteries enabled by localized high-concentration electrolytes. Adv. Mater. 30, 1706102 (2018).

Hai, F. et al. A low-cost, fluorine-free localized highly concentrated electrolyte toward ultra-high loading lithium metal batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 14, 2304253 (2024).

Haynes, W. M. CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics 94th edn (CRC, 2013).

Ko, S. et al. Electrode potential influences the reversibility of lithium-metal anodes. Nat. Energy 7, 1217–1224 (2022).

Xie, J. et al. Engineering stable interfaces for three-dimensional lithium metal anodes. Sci. Adv. 4, eaat5168 (2018).

Zhang, H. et al. Titration mass spectroscopy (TMS): a quantitative analytical technology for rechargeable batteries. Nano Lett. 22, 9972–9981 (2022).

Aiken, C. P. et al. An apparatus for the study of in situ gas evolution in Li-ion pouch cells. J. Electrochem. Soc. 161, A1548 (2014).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 154014 (2010).

Henkelman, G., Uberuaga, B. P. & Jónsson, H. A climbing image nudged elastic band method for finding saddle points and minimum energy paths. J. Chem. Phys. 113, 9901–9904 (2000).

Zhang, H., Qiu, L. & Hu, D. Finite-temperature dimer method for finding saddle points on free energy surfaces. J. Comput. Chem. 40, 1701–1706 (2019).

Becke, A.-D. Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 98, 5648–5652 (1993).

Frisch, M. J. et al. Gaussian 09, Revision B. 01 (Gaussian Inc., 2009).

Marenich, A. V., Cramer, C. J. & Truhlar, D. G. Universal solvation model based on solute electron density and on a continuum model of the solvent defined by the bulk dielectric constant and atomic surface tensions. J. Phys. Chem. B 113, 6378–6396 (2009).

Klamt, A. Conductor-like screening model for real solvents: a new approach to the quantitative calculation of solvation phenomena. J. Phys. Chem. 99, 2224–2235 (1995).

Klamt, A. & Eckert, F. COSMO-RS: a novel and efficient method for the a priori prediction of thermophysical data of liquids. Fluid Phase Equilib. 172, 43–72 (2000).

Ahlrichs, R., Bär, M., Häser, M., Horn, H. & Kölmel, C. Electronic structure calculations on workstation computers: the program system Turbomole. Chem. Phys. Lett. 162, 165–169 (1989).

Eckert, F. & Klamt, A. C. COSMOtherm Version C3.0, Release 12.01 (COSMOlogic GmbH & Co. KG, 2013).

Hadj-Kali, M. K. et al. Screening of ionic liquids for gas separation using COSMO-RS and comparison between performances of ionic liquids and aqueous alkanolamine solutions. Chem. Eng Commun. 207, 1264–1277 (2020).

Plimpton, S. Fast parallel algorithms for short-range molecular dynamics. J. Comput. Phys. 117, 1–19 (1995).

Stukowski, A. Visualization and analysis of atomistic simulation data with OVITO—the Open Visualization Tool. Model. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng 18, 015012 (2010).

Jorgensen, W. L., Maxwell, D. S. & Tirado-Rives, J. Development and testing of the OPLS all-atom force field on conformational energetics and properties of organic liquids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118, 11225–11236 (1996).

Dodda, L. S., Vaca, I. C., Tirado-Rives, J. & Jorgensen, W. L. LigParGen web server: an automatic OPLS-AA parameter generator for organic ligands. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, W331–W336 (2017).

Nichol, A. & Ackland, G. J. Property trends in simple metals: an empirical potential approach. Phys. Rev. B 93, 184101 (2016).

Hoover, W. G. Canonical dynamics: equilibrium phase-space distributions. Phys. Rev. A 31, 1695–1697 (1985).

Siepmann, J. I. & Sprik, M. Influence of surface topology and electrostatic potential on water/electrode systems. J. Chem. Phys. 102, 511–524 (1995).

Reed, S. K., Lanning, O. J. & Madden, P. A. Electrochemical interface between an ionic liquid and a model metallic electrode. J. Chem. Phys. 126, 084704 (2007).

Wang, Z., Yang, Y., Olmsted, D. L., Asta, M. & Laird, B. B. Evaluation of constant potential method in simulating electric double-layer capacitors. J. Chem. Phys. 141, 184102 (2014).

Ahrens-Iwers, L. J. V., Janssen, M., Tee, S. R. & Meißner, R. H. ELECTRODE: an electrochemistry package for atomistic simulations. J. Chem. Phys. 157, 084801 (2022).

Thorat, I. V. et al. Quantifying tortuosity in porous Li-ion battery materials. J. Power Sources 188, 592–600 (2009).

Acknowledgements

H.W. acknowledges the support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China under grant number 22209085 and the Fujian Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China under grant number 2024J010048. C.O. acknowledges the support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China under grant number 51962010. This work is also supported by funds from Contemporary Amperex Technology Co., Limited (CATL). We acknowledge Z. Yu at the College of Chemistry, Fuzhou University, for providing STEM facilities. We acknowledge D. Yanchao from Shanghai Nanoport, ThermoFisher Scientific, for providing the STEM facilities and assisting the experiments. We acknowledge China Energy Lithium Co., Ltd., for providing 5 μm, 10 μm, 15 μm and 20 μm thin Li foil samples.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.W., X.G., C.L., N.L. and C.O. conceived the idea and designed the experiments. X.Y., H.W., H.L. and F.C. developed and performed the T-DEMS experiments. R.Z., F.Y., H.W. and H.L. developed and performed the E-G&IC experiments. X.Y. performed the ICP-OES. J.S., E.W. and B.X. performed the first-principles and molecular dynamics simulations. F.F. optimized the electrolyte formulations. X.Y. and J.L. performed the electrochemical simulations. Y.W., P.W., H.L. and F.C. performed the DEMS experiments on the gassing of LMBs. G.Y. performed the XPS. S.H. performed the NMC811 degradation tests. X.L. and J.Z. performed the TEM and STEM characterizations. H.W. analysed the data and organized the paper. U.U., X.Y. and S.T.H. revised the paper. All authors discussed the results and commented on the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

All authors are employed by Contemporary Amperex Technology Co., Limited (CATL).

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Nanotechnology thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–34, Tables 1–10, Notes 1–12 and References.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, H., Yan, X., Zhang, R. et al. Application-driven design of non-aqueous electrolyte solutions through quantification of interfacial reactions in lithium metal batteries. Nat. Nanotechnol. 20, 1034–1042 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41565-025-01935-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41565-025-01935-y