Abstract

The emergent properties of materials are governed by the symmetries of their underlying atomic, spin and charge order. Therefore, intrinsic material properties usually constrain the exploration of symmetry-breaking effects. Focused ion beam (FIB) fabrication now enables the structuring of bulk crystals into ultraprecise transport devices, allowing the study of geometrical symmetry breaking on mesoscopic length scales. Here we extend FIB nanostructuring into three-dimensional, curvilinear geometries. Using single crystals of the high-mobility, centrosymmetric magnetic Weyl semimetal Co3Sn2S2, we sculpt helices with lengths of 3–14 μm, diameters of 1–4 μm and pitches ranging from 500 nm to 2 μm. Lock-in measurements on the helical devices at temperatures between 10 K and 190 K show that the combination of imposed inversion symmetry-breaking geometry and ferromagnetism yields non-reciprocal electron transport—or diode effect—at zero applied magnetic field, exceeding classical self-field expectations by orders of magnitude at low temperatures. We attribute this behaviour to the quasi-ballistic motion of carriers as the mean free path approaches the length scale of the chiral device geometry. Finally, we show that current pulses can switch the magnetization of the device. These results highlight the potential of FIB nanosculpting to engineer symmetry and functionality beyond conventional device geometries.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All experimental data are available via Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17163308 (ref. 58).

References

Fiebig, M., Lottermoser, T., Meier, D. & Trassin, M. The evolution of multiferroics. Nat. Rev. Mater. 1, 1–14 (2016).

Armitage, N. P., Mele, E. J. & Vishwanath, A. Weyl and Dirac semimetals in three-dimensional solids. Rev. Mod. Phys. 90, 015001 (2018).

Nagaosa, N. & Tokura, Y. Topological properties and dynamics of magnetic skyrmions. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 899–911 (2013).

Fert, A., Reyren, N. & Cros, V. Magnetic skyrmions: advances in physics and potential applications. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2, 1–15 (2017).

Manchon, A. et al. Current-induced spin–orbit torques in ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic systems. Rev. Mod. Phys. 91, 035004 (2019).

Yang, S.-H., Naaman, R., Paltiel, Y. & Parkin, S. S. P. Chiral spintronics. Nat. Rev. Phys. 3, 328–343 (2021).

Fernández-Pacheco, A. et al. Three-dimensional nanomagnetism. Nat. Commun. 8, 15756 (2017).

Sheka, D. D. A perspective on curvilinear magnetism. Appl. Phys. Lett. 118, 230502 (2021).

Gubbiotti, G. et al. 2025 roadmap on 3D nanomagnetism. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 37, 143502 (2025).

Fernández-Pacheco, A. et al. Three dimensional magnetic nanowires grown by focused electron-beam induced deposition. Sci. Rep. 3, 1492 (2013).

Zhakina, E. et al. Reconfigurable three-dimensional superconducting nanoarchitectures. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2506057 (2025).

Donnelly, C. et al. Element-specific X-ray phase tomography of 3D structures at the nanoscale. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 115501 (2015).

Meng, F. et al. Non-planar geometrical effects on the magnetoelectrical signal in a three-dimensional nanomagnetic circuit. ACS Nano 15, 6765–6773 (2021).

Donnelly, C. et al. Complex free-space magnetic field textures induced by three-dimensional magnetic nanostructures. Nat. Nanotechnol. 17, 136–142 (2022).

Farinha, A. M. A., Yang, S.-H., Yoon, J., Pal, B. & Parkin, S. S. P. Interplay of geometrical and spin chiralities in 3D twisted magnetic ribbons. Nature 639, 67–72 (2025).

Moll, P. J. W. et al. Field-induced density wave in the heavy-fermion compound CeRhIn5. Nat. Commun. 6, 6663 (2015).

Moll, P. J. W. Focused ion beam microstructuring of quantum matter. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 9, 147–162 (2018).

Guo, C. et al. Switchable chiral transport in charge-ordered kagome metal CsV3Sb5. Nature 611, 461–466 (2022).

Höflich, K. et al. Roadmap for focused ion beam technologies. Appl. Phys. Rev. 10, 041311 (2023).

Turnbull, L. A. et al. Interlinking helical spin textures in nanopatterned chiral magnets. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2511.11372 (2025).

Liu, E. et al. Giant anomalous Hall effect in a ferromagnetic kagome-lattice semimetal. Nat. Phys. 14, 1125–1131 (2018).

Morali, N. et al. Fermi-arc diversity on surface terminations of the magnetic Weyl semimetal Co3Sn2S2. Science 365, 1286–1291 (2019).

Rikken, G. L. J. A., Fölling, J. & Wyder, P. Electrical magnetochiral anisotropy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 236602 (2001).

Wakatsuki, R. et al. Nonreciprocal charge transport in noncentrosymmetric superconductors. Sci. Adv. 3, e1602390 (2017).

Tokura, Y. & Nagaosa, N. Nonreciprocal responses from non-centrosymmetric quantum materials. Nat. Commun. 9, 3740 (2018).

Atzori, M., Train, C., Hillard, E. A., Avarvari, N. & Rikken, G. L. J. A. Magneto-chiral anisotropy: from fundamentals to perspectives. Chirality 33, 844–857 (2021).

Yokouchi, T. et al. Electrical magnetochiral effect induced by chiral spin fluctuations. Nat. Commun. 8, 866 (2017).

Ideue, T. et al. Bulk rectification effect in a polar semiconductor. Nat. Phys. 13, 578–583 (2017).

Tanaka, M. et al. Topological kagome magnet Co3Sn2S2 thin flakes with high electron mobility and large anomalous Hall effect. Nano Lett. 20, 7476–7481 (2020).

He, Y. et al. Large linear non-saturating magnetoresistance and high mobility in ferromagnetic MnBi. Nat. Commun. 12, 4576 (2021).

Morimoto, T. & Nagaosa, N. Chiral anomaly and giant magnetochiral anisotropy in noncentrosymmetric Weyl semimetals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 146603 (2016).

Wang, Y. et al. Gigantic magnetochiral anisotropy in the topological semimetal ZrTe5. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 176602 (2022).

Yang, S.-Y. et al. Field-modulated anomalous Hall conductivity and planar Hall effect in Co3Sn2S2 nanoflakes. Nano Lett. 20, 7860–7867 (2020).

Maurenbrecher, H. et al. Chiral anisotropic magnetoresistance of ferromagnetic helices. Appl. Phys. Lett. 112, 242401 (2018).

Parrott, J. E. A new theory of the size effect in electrical conduction. Proc. Phys. Soc. 85, 1143 (1965).

Baringhaus, J. et al. Exceptional ballistic transport in epitaxial graphene nanoribbons. Nature 506, 349–354 (2014).

Moll, P. J. W., Kushwaha, P., Nandi, N., Schmidt, B. & Mackenzie, A. P. Evidence for hydrodynamic electron flow in PdCoO2. Science 351, 1061–1064 (2016).

Bachmann, M. D. et al. Directional ballistic transport in the two-dimensional metal PdCoO2. Nat. Phys. 18, 819–824 (2022).

Yasuda, K. et al. Large non-reciprocal charge transport mediated by quantum anomalous Hall edge states. Nat. Nanotechnol. 15, 831–835 (2020).

Evers, F. et al. Theory of chirality induced spin selectivity: progress and challenges. Adv. Mater. 34, 2106629 (2022).

Shitade, A. & Minamitani, E. Geometric spin–orbit coupling and chirality-induced spin selectivity. New J. Phys. 22, 113023 (2020).

Song, A. M. et al. Nonlinear electron transport in an asymmetric microjunction: a ballistic rectifier. Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 3831–3834 (1998).

Kida, N. et al. Optical magnetoelectric effect in a submicron patterned magnet. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 077205 (2005).

Isobe, H. & Nagaosa, N. Toroidal scattering and nonreciprocal transport by magnetic impurities. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn 91, 115001 (2022).

Gaididei, Y., Kravchuk, V. P. & Sheka, D. D. Curvature effects in thin magnetic shells. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 257203 (2014).

Ishizuka, H. & Nagaosa, N. Anomalous electrical magnetochiral effect by chiral spin-cluster scattering. Nat. Commun. 11, 2986 (2020).

Yamaguchi, D., Kitaori, A., Nagaosa, N. & Tokura, Y. Magnetoelectric control of spin helicity and nonreciprocal charge transport in a multiferroic metal. Adv. Mater. 37, 2420614 (2025).

Nakamura, D. et al. Nonreciprocal transport in a room-temperature chiral magnet. Sci. Adv. 11, eadw8023 (2025).

Jiang, N., Nii, Y., Arisawa, H., Saitoh, E. & Onose, Y. Electric current control of spin helicity in an itinerant helimagnet. Nat. Commun. 11, 1601 (2020).

Masuda, H. et al. Room temperature chirality switching and detection in a helimagnetic MnAu2 thin film. Nat. Commun. 15, 1999 (2024).

González-Hernández, R., Ritzinger, P., Výborný, K., Železný, J. & Manchon, A. Non-relativistic torque and Edelstein effect in non-collinear magnets. Nat. Commun. 15, 7663 (2024).

Ando, F. et al. Observation of superconducting diode effect. Nature 584, 373–376 (2020).

Nadeem, M., Fuhrer, M. S. & Wang, X. The superconducting diode effect. Nat. Rev. Phys. 5, 558–577 (2023).

Pop, F., Auban-Senzier, P., Canadell, E., Rikken, G. L. J. A. & Avarvari, N. Electrical magnetochiral anisotropy in a bulk chiral molecular conductor. Nat. Commun. 5, 3757 (2014).

Krstić, V., Roth, S., Burghard, M., Kern, K. & Rikken, G. L. J. A. Magneto-chiral anisotropy in charge transport through single-walled carbon nanotubes. J. Chem. Phys. 117, 11315–11319 (2002).

Varnavides, G., Yacoby, A., Felser, C. & Narang, P. Charge transport and hydrodynamics in materials. Nat. Rev. Mater. 8, 726–741 (2023).

Ding, L. et al. Quantum oscillations, magnetic breakdown and thermal Hall effect in Co3Sn2S2. J. Phys. Appl. Phys. 54, 454003 (2021).

Birch, M. T. et al. Dataset for: Nanosculpted 3D helices of a magnetic Weyl semimetal with switchable nonreciprocal electron transport. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17163308 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the assistance and guidance of the CEMS Semiconductor Science Research Support Team for the use of cleanroom facilities. We are grateful to members of CEMS as well as H. Isobe, L. Turnbull, C. Donnelly, A. Fernández-Pacheco and M. Hirschberger for the fruitful discussions. This work was supported in part by JSPS KAKENHI (grant nos 23H05431, Y.T.; and 24H00197, 24H02231 and 24K00583, N.N.), the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST) CREST programme (grant no. JPMJCR20T1, X.Y.) and the RIKEN TRIP initiative. M.T.B. acknowledges the support of the RIKEN Special Postdoctoral Researcher Program and the RIKEN Incentive Research Project scheme.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.T.B., N.N., M.K. and Y.T. conceived the project. Y.F. grew the bulk Co3Sn2S2 single crystal. M.T.B. fabricated the FIB devices with support from Y.-L.C. and X.Y. M.T.B. performed the transport measurements and data analysis with support from Y.F., I.B., M.M. and M.K. Y.-L.C. and X.Y. performed the TEM measurements and analysis. Z.L. carried out the COMSOL simulations. M.T.B., N.N. and Y.T. interpreted the data and wrote the paper, along with input and contributions from all coauthors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Nanotechnology thanks Enke Liu and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

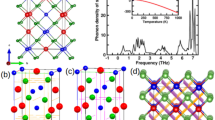

Extended Data Fig. 1 Focused ion beam sculpted devices of Co3Sn2S2.

a-f Resistance measured as a function of temperature, and scanning electron micrographs of the six investigated focused ion beam-fabricated devices, with helical pitch L, rod radius R, conducting cross sectional area A, and contact separation D: a, left-handed (LH) helix with L = 1.0 μm, R = 1.0 μm, A = ~ 0.18 μm2, D = 16.4 μm. b, right-handed (RH) helix with L = 1.0 μm, R = 1.0 μm, A = ~ 0.18 μm2, D = 16.8 μm. c, achiral (AC) rod with A = ~ 0.23 μm2, rod length = 9.8 μm and D = 15.9 μm. d, LH helix with L = 0.5 μm, R = 0.5 μm, A = ~ 0.06 μm2, D = 10 μm. e, RH helix with L = 2.0 μm, R = 2.1 μm, A = ~2 μm2, D = 25.7 μm. f, Hall bar with thickness 1.6 μm, width 4.1 μm, and contact separation (widest separation) 15.7 μm. In all cases, the Co3Sn2S2 structures were fabricated by Ga ion milling, and fixed to patterned Au electrodes on Al2O3 substrates with in-situ Pt deposition. All scale bars are 10 μm.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Co3Sn2S2 helix device fabrication.

a A schematic illustration of the helix device FIB fabrication process. b Scanning electron micrograph of comb-like Co3Sn2S2 structure, fabricated from a slab extracted from the bulk single crystal, and attached to the copper grid. The scale bar is 10 μm. c A single Co3Sn2S2 rod is picked up by the micromanipulator and transferred to another copper grid, where the scale bar is 5 μm. d The rod is milled with a thread-like pattern from several angles to create the helical shape. The scale bar is 1 μm. e The finished helix-shaped sample is picked up by the micromanipulator and transferred to the Al2O3 substrate and fixed via Pt deposition to the prepatterned Au contacts, creating the final device structure.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Transmission electron microscopy analysis.

a Scanning electron micrograph of an additional helical Co3Sn2S2 sample, prepared using the identical fabrication process, but made thinner to facilitate the transmission imaging. The scale bar is 1 μm. b Thickness map obtained from electron energy-loss spectroscopy (EELS). The inset shows a line profile taken from the top to bottom of the helix, as indicated by the dashed white rectangle, showing a central thickness of ~ 300 nm, tapering to below 150 nm at the edges, making these areas suitable for high-resolution TEM imaging. The scale bar is 500 nm. c TEM image at the outer edge of the example spiral. A ~ 4 nm thick layer consisting of a mixture of amorphous and polycrystalline phases is observed, caused by the ion beam damage during FIB fabrication. The scale bar is 10 nm. d High-resolution TEM image of the region marked by the blue square in c. Clear ordered lattice fringes are observed within the bulk of the helix, confirming the preservation of the single crystalline structure, and indicating that the core Co3Sn2S2 material remains largely unaffected by the FIB fabrication. The scale bar is 5 nm.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Crossover in dominant scattering and nonreciprocal scattering mechanisms.

a-e The upper panels show the first harmonic resistance \({R}_{{xx}}^{1\omega }\) measured as a function of magnetic field, for the left-handed (LH) helix with pitch length L = 1.0 μm, at a range of temperatures and an AC current of 40 μA. The lower panels show the second harmonic resistance \({R}_{{xx}}^{2\omega }\) measured under the same conditions. The result of the self-field estimation is plotted in grey, and has been multiplied by a factor of 30 for comparison. In both cases, there is a crossover behavior as a function of temperature: the scattering and nonreciprocity at low temperature is dominated by the positive, ordinary magnetoresistance, typical of high mobility systems; while at high temperature the temperature-fluctuation spin/magnon scattering, negative magnetoresistance is the main contribution.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Current-induced magnetisation switching efficacy.

a The second harmonic voltage \({V}_{x}^{2\omega }\) measured as a function of magnetic field at 150 K, for the left-handed (LH) helix with pitch length L = 0.5 μm, with an AC current of 40 μA. b The response of the device in the current-induced switching experiment, showing the measured change in the second harmonic longitudinal voltage \(\Delta {V}_{x}^{2\omega }\) at 150 K and zero applied magnetic field, plotted as a function of t, and measured with an AC current of 40 μA. In both plots, the horizontal coloured lines are a guide to the eye. Comparison of the change in \({V}_{x}^{2\omega }\) indicates that close to 100% of the magnetisation is reversed within the helical device.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Characterisation of the Co3Sn2S2 Hall bar device.

a Hall angle, calculated as the ratio of Hall and longitudinal conductivities, σxy/σxx measured as a function of temperature under an applied magnetic field of 3 T. b From the same temperature dependent data, the Hall conductivity is plotted as a function of the longitudinal conductivity. The constant value of σxy over a range of temperatures is commonly taken as an indication of the intrinsic nature of the anomalous Hall conductivity, which here is clearly preserved in the device after focused ion beam patterning. c, d The longitudinal and Hall resistivities, ρxx and ρyx measured as a function of applied magnetic field B at 10 K. e, f The corresponding calculated longitudinal and Hall conductivities at 10 K.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Current dependent measurements of nonreciprocal helical Co3Sn2S2 devices.

a-c First harmonic resistance \({R}_{{xx}}^{1\omega }\) measured as a function of magnetic field B at 10 K with an AC current of 10 μA, for the helical devices with pitch length L = 0.5, 1.0 and 2.0 μm. d-f The antisymmetrised second harmonic voltage \({V}_{x}^{2\omega }\) measured at 10 K with various AC currents, demonstrating the expected I2 scaling for all three devices.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Fitting the current dependent measurements.

The ratio of the second to first harmonic resistances, \({R}_{{xx}}^{2\omega }/{R}_{{xx}}^{1\omega },\) at 10 K and zero applied magnetic field, plotted as a function of the applied current I for the three helical devices with pitch lengths L = 0.5, 1.0 and 2.0 μm, as labelled. Error bars indicate the standard error across 10 data points around B = 0, dominated by the noise in the \({R}_{{xx}}^{2\omega }\) measurement. The linear fits give a value for Γ of each device via the gradient, which is plotted as a function of L in the inset.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Field angle dependent measurements.

a The resistance \({R}_{{xx}}^{1\omega }\) of the right handed (RH) L = 2.0 μm device measured as a function of applied magnetic field B (at angle θ = 90°, indicated in the inset diagram) at 10 K and with an AC current of 140 μA. b The corresponding second harmonic resistance \({R}_{{xx}}^{2\omega }\). c-f The same as a and b, but at θ = 45° and 0°.

Extended Data Fig. 10 Field angle rotation measurements.

a The resistance \({R}_{{xx}}^{1\omega }\) of the right handed (RH) L = 2.0 μm device measured as a function of the applied magnetic field angle θ (indicated in the inset diagram) at 10 K, with an applied magnetic field of 14 T and an AC current of 140 μA. Red and blue indicate up and down measurement directions. b The corresponding second harmonic resistance \({R}_{{xx}}^{2\omega }\). c, d The same as a and b, but at an applied magnetic field of 5 T.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Notes 1 and 2, and Figs. 1–4.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Birch, M.T., Fujishiro, Y., Belopolski, I. et al. Nanosculpted 3D helices of a magnetic Weyl semimetal with switchable non-reciprocal electron transport. Nat. Nanotechnol. (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41565-025-02104-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41565-025-02104-x