Abstract

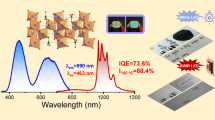

Organic LEDs that emit light in the short-wavelength infrared (SWIR) region, which spans the 1–2 μm region, are attractive for applications in biosensors, biomedical imaging and spectroscopy, and surveillance. However, fabrication of such devices with high radiance has not yet been achieved owing to an intrinsic limitation imposed by the energy-gap law, which leads to extremely low emission efficiencies. Here, we report that acceptor–donor–acceptor-type molecules with high coplanarity, rigid π-conjugated backbones, an extremely small reorganization energy and an electron–phonon coupling factor are capable of simultaneously providing a strongly suppressed non-radiative recombination rate and a high operation stability at high current density. We achieve electrically driven SWIR organic LEDs with an irradiance of up to 3.9 mW cm−2 (corresponding to 7% of direct sunlight infrared irradiance). These findings should open a wide avenue to a new class of organic SWIR light sources for a broad range of applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Organic semiconductors with advantageous electronic and optoelectronic properties have enabled the demonstration of high-performance organic light-emitting devices (OLEDs) with emission covering the visible, near-ultraviolet and near-infrared (NIR) parts of the electromagnetic spectrum1,2,3,4,5. There has been a long-standing demand for the development of electrically driven SWIR (that is, 1,000–2,000 nm)6,7 light sources in view of their broad range of applications, including optical communications3,4,5, night-vision surveillance3,4,6 and remote sensing8. Recent emerging applications in biological imaging9,10,11, medical analysis12 and infrared spectroscopy9 for health, food and environmental monitoring have required the development of bright, biocompatible SWIR emitters since longer imaging wavelengths promise lower light scattering, a deeper tissue penetration depth and superior spatiotemporal resolution9,10,11 compared with the visible and NIR (700–1,000 nm) counterparts. More recently, SWIR light sources have been integrated in smartphones for providing security authentication and photonic sensing functionalities4,13, thereby enabling fast and convenient face and iris recognition. Currently, high-performance SWIR emitters are generally made from group III–V compound semiconductors7,14 using molecular beam epitaxy or metal organic chemical vapour deposition. Compared with other solution-processable alternatives7, two major hindrances for these SWIR light sources are their point source characteristics15, with typical diameters of a few hundreds of micrometres, and their low degree of mechanical flexibility16, owing to the high Young’s modulus (for example, ~130 GPa for silicon), which limit their potential applications in wearable and implanted electronic devices.

Among the emerging candidates for large-area planar SWIR light sources, OLEDs have been identified as particularly unique since they have the combined advantages of high-throughput fabrication at extremely low costs, being lightweight, having mechanical flexibility, tunable chemical, physical and emission-wavelength properties, and being compatible for use in large-area devices1,2,3. Furthermore, purely organic fluorescence emitters are free of heavy metals, which increases their biocompatibility and environmental sustainability, thus making them ideal for health, food and environmental applications where biocompatibility, toxicity and environmental issues must be considered4. To translate these advantages to widespread SWIR applications, high-radiance/brightness OLEDs are necessary for obtaining a satisfactory performance and for device miniaturization. However, unlike their success in the visible1 and NIR regions3,4,5,13,17,18, bright OLEDs in the SWIR range have not been demonstrated so far. The main reason for this could be ascribed to the limitation imposed by the energy-gap law3,4,5, which predicts an exponentially increased non-radiative decay rate with decreasing energy gap in organic solids as a result of increased electron–phonon coupling between the excited and ground states. This limitation indicates that, if the energy-gap law is strictly valid, long-wavelength emission from organic solids is extremely weak and there is a major bottleneck for extending the emission to longer wavelengths.

Despite such a major fundamental hurdle, extensive research efforts have been devoted to narrowing the energy gap and realizing electroluminescence (EL) beyond the visible region, that is, 700–1,000 nm NIR emission in organic solids3,4,5, by adopting rational strategies that are used for visible emitters. These strategies generally involve several key considerations3,4,5, such as extending the conjugation length, reducing bond length alternation (corresponding to greater π-electron delocalization), the introduction of appropriate donor–acceptor charge-transfer units and the use of triplet19 or doublet excitons20. As a result, organic emitters that are available nowadays for NIR OLEDs include mainly organometallic phosphorescent complexes21,22, organic ionic dyes23, conjugated polymers24, organic compounds containing donor–acceptor charge-transfer chromophores3,5,18,25,26,27, thermally activated delayed fluorescent materials28 and doublet emitters20. In 2020, Wei et al. reported state-of-the-art phosphorescent NIR OLEDs by exploiting a series of 5-(2-pyridyl)pyrimidinate Pt(II) complexes, achieving an EL emission maximum at 930 nm, with an external quantum efficiency (EQE) of 2.14% and a remarkable maximum radiant exitance of 13.06 mW cm−2 (ref. 22). Yu et al. demonstrated high-performance fluorescent NIR OLEDs based on anthracene-cored emitters, which exhibit EL peaks at 838 nm and 916 nm with EQE values of 0.58% and 0.07%, while the maximum radiant exitance is 2.8 mW cm−2 and 0.29 mW cm−2, respectively29. More recently, progress in fluorescent NIR OLEDs has been made by Minotto et al., who achieved an EQE of 1.1% with an EL emission maximum at 850 nm and a maximum radiant exitance of 1.9 mW cm−2 (ref. 13). However, previous studies have shown that OLEDs emitting at longer wavelengths (for example, beyond 1,000 nm and extending into the SWIR region) always suffer from severe non-radiative recombination loss, leading to low EQE values of the order of 0.01% (refs. 24,30). In 2009, Qian et al. reported a series of pure organic emitters based on a benzobisthiadiazole derivative that emitted at wavelengths beyond 1,000 nm (ref. 3). Non-doped devices based on a chromophore featuring triphenylamine derivatives as the acceptor group exhibited a state-of-the-art EQE of 0.28% and an EL peak at 1,080 nm, with a maximum radiant exitance around 0.06 mW cm−2. Although the radiant exitance and EQE of an OLED based on a different chromophore were too low for practical applications, its EL peak at 1,220 nm was one of the longest emission wavelengths for pure organic emitters reported so far, demonstrating the promising potential of organic chromophores as SWIR emitters for further development. Ever since the recent emergence of a new class of aromatic fused-ring electron acceptors with an acceptor–donor–acceptor (A–D–A) structure, the development of organic solar cells has entered into a new era, featuring the coincidence of efficient charge separation and low voltage losses31. Owing to the strong intramolecular charge-transfer effect and the rigid planarity configuration of the fused rings, the π-electron delocalization in these A–D–A-type organic semiconductors is enhanced, producing a reduction in the bandgap and a greater oscillator strength that increases the NIR absorption coefficient. Moreover, A–D–A-type organic semiconductors show several additional great merits that are essential for minimizing energy losses in organic solar cells. These include a sharp optical absorption edge, a suppressed non-radiative recombination rate, low energetic disorder and a high luminescence (radiative recombination) yield, which play an important role in obtaining a high photovoltage32. According to the reciprocity relationship that exists between light absorption and emission33, such organic semiconductors that are ideal for solar cells are likewise ideal for LEDs.

Results and discussion

Computational results

Before attempting to exploit A–D–A-type organic semiconductors for SWIR emitter applications, density functional theory (DFT) and time-dependent DFT (TD-DFT) approaches at the ωB97XD/6-31G(d,p) level with the optimally tuned ω parameter were used to study the structural regularity and excited-state properties for three typical narrow-bandgap molecules with low photon energy loss in organic solar cells, that is, Y11 (ref. 32), IDSe-4Cl (Supplementary Methods) and COTIC-4F (ref. 34) (see Fig. 1a–c for chemical structures and the Methods section for computational details). Our DFT calculation results displayed a small dihedral angle of 14° for Y11, whereas nearly planar structures with negligible torsion in their relaxed geometries were observed for IDSe-4Cl and COTIC-4F (Supplementary Fig. 1). The success of this design strategy was confirmed via the extended emissive exciton wavefunctions, as shown by the calculated natural transition orbitals (NTOs) that describe the first singlet (S1) excited states (see Fig. 1d). The NTO hole and electron wavefunctions of the S1 excitons are spread over the whole π-conjugated backbones, implying strong electronic couplings between the donor and acceptor moieties. In conjunction with the alternating electron-withdrawing and electron-releasing moieties that incur an intramolecular charge-transfer effect4,5, the enhanced wavefunction delocalization and the extended planarity of the A–D–A molecules ensure minimized optical bandgap energies35 (Eg) of 1.37, 1.27 and 1.17 eV for Y11, IDSe-4Cl and COTIC-4F, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 2), which is envisaged to lead to SWIR emissions beyond 1,000 nm. More importantly, the significant spatial overlaps (Oh/e) between the NTO-hole and NTO-electron give rise to very large oscillator strength (f) values of 2.3, 3.2 and 3.0 for Y11, IDSe-4Cl and COTIC-4F, respectively36, corresponding to their high radiative recombination rates, as discussed below.

a–c, Molecular structures of representative SWIR-emitting organic molecules Y11 (a), IDSe-4Cl (b) and COTIC-4F (c). d, NTO (hole and electron) wavefunctions, showing values for the adiabatic excited-state energy (\(E_{{\mathrm{S}}_{1}}\)), total reorganization energy (\(\lambda_{{\mathrm{S}}_{1}} = \lambda_{{\mathrm{s}}} + \lambda_{{\mathrm{v}}}\)), which includes the two modes due to low-frequency (λs) and high-frequency (λv) vibrations, the oscillator strength (f) and overlap between NTO electron and hole orbitals (Oh/e) for the first singlet (S1) excited states of Y11, IDSe-4Cl and COTIC-4F, calculated at the ωB97XD/6-31G(d,p) level using the optimally tuned ω parameter. For computational details, see the Methods section.

Photophysical properties and numerical simulations

To further illustrate their potential as a new type of SWIR emitter, the absorption and photoluminescence (PL) spectra of the three molecules were measured. As shown in Fig. 2a–c, the thin-film spectra of the three molecules exhibit sharp absorption bands with a dominant peak slightly above the optical gap and a low-energy shoulder adjacent to it. Owing to its overwhelmingly high oscillator strength, transition from the ground state (S0) to the first excited state (S1) induces an intense absorption peak, which, consequently, surpasses the intensities of other transitions. Following Kasha’s rule, fast thermalization to the first excited state occurs before transition that leads to radiative recombination could take place, such that the higher energy electronic transitions should play a minimal part in the PL, and the PL spectra are dominated by the S1 → S0 transition only. The low-energy shoulders found in the PL spectra are thus confirmed to be an outcome of high-frequency vibrational modes of the molecules37,38.

a–c, Absorption (Abs.) and PL spectra of the SWIR emitters Y11 (a), IDSe-4Cl (b) and COTIC-4F (c) as solid films, measured in air at room temperature. d–f, Normalized reduced emissions for the respective SWIR emitters deduced from the measured PL through equation (1), the corresponding curves fitted by multiple Gaussian peaks, and the emission spectra modelled using equation (2), with the extracted parameters as input also being shown. g, The modelled PLQY data using specific photophysical parameters extracted from Y11, IDSe-4Cl and COTIC-4F plotted as a function of the optical gap, where their experimentally measured PLQY values are shown as scattered dots for comparison.

Meanwhile, we propose a model based on established theories39,40,41 to describe these vibrational pathways through which unfavourable non-radiative recombination takes place. According to the model, the optical emission intensity Iemission at a specific photon energy hν (h, Planck’s constant; ν, photon frequency) is proportional to the oscillator strength f that embodies the electronic transition dipole moment as well as the Franck–Condon-weighted density of states (FCWD) that describes the wavefunction overlap between the vibrational levels of excited and ground states, while adopting the Born–Oppenheimer approximation (Supplementary Note 1):

with

in which kB is the Boltzmann constant and T is the temperature. Here, FCWD(hν) is further governed by three vibrational parameters: the low-frequency reorganization energy λs that describes the conformational changes of the molecule and its surroundings upon excitation; the energy of the high-frequency vibrational mode \(h\bar \nu_{\mathrm{v}}\) in which \(\bar \nu_{\mathrm{v}}\) is the average of the frequencies of atomic vibrations within the molecule; and the electron–phonon coupling factor S, which is related to the high-frequency reorganization energy λv that results from atomic displacements upon charging to the aforementioned mean phonon energy \(h\bar \nu_{\mathrm{v}}\) by \(S = \lambda _{\mathrm{v}}/(h\bar \nu_{\mathrm{v}})\). The lineshape of the reduced emission spectra where the emission spectra are divided by (hν)3 are therefore intricately modulated by these vibrational parameters through equation (2).

Careful fitting of the measured PL spectra via equations (1) and (2) enabled the extraction of vibrational parameters for our molecules, as shown in Fig. 2d–f, with details provided in Supplementary Note 2. Very low λs values ranging from 0.045 to 0.06 eV are obtained for these molecules, which correspond to their narrow linewidths. The observations are also consistent with the noticeably reduced Stokes shifts, as indicated in Fig. 2a–c. Overall, these findings suggest that photo-excitation and the subsequent decay barely trigger the deformation of their molecular geometry, which is a result of the enhanced planarity and rigidity of these A–D–A molecules. Owing to their narrow linewidths, the mean phonon energy \(h\bar \nu_{\mathrm{v}}\), which ranges from 0.12 to 0.14 eV for the molecules, can be readily determined via the small energy shift from the pronounced 0–0 peaks to the 0–1 vibrational shoulders (Supplementary Fig. 3). As such, the experimental values are considerably lower than the characteristic value of 0.16 eV for the predominant carbon–carbon bonds and ring-stretching modes in organic molecules37,40,42. Finally, values for the electron–phonon coupling factor S in the range of 0.7–0.9 are extracted for the molecules. Through fitting of the emission spectrum lineshapes, the obtained values of 0.17, 0.14 and 0.15 eV for Y11, IDSe-4Cl and COTIC-4F, respectively, for the estimated total reorganization energy (\(\lambda_{{\mathrm{S}}_{1}} = \lambda_{{\mathrm{s}}} + \lambda_{{\mathrm{v}}}\)), which includes the two parts due to the low- and high-frequency vibrations, are highly consistent with our TD-DFT calculation results, that is, 0.13, 0.13 and 0.15 eV, respectively, indicating the reliability of our fitting via equations (1) and (2).

Substituting all the previously obtained parameters into Fermi’s golden rule, the rate constant of non-radiative recombination knr can be derived:

with the electronic coupling Vc approximated by the generalized Mulliken–Hush method41,43 (Supplementary Note 1).

The photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) can eventually be determined via \({{{\mathrm{PLQY}}}} = \frac{{k_{\mathrm{r}}}}{{k_{\mathrm{r}} + k_{{\mathrm{nr}}}}}\), where kr is the rate constant of radiative recombination. The calculated PLQY values for a set of representative parameters are plotted against the bandgap in Fig. 2g. The PLQY data show a dramatic decrease as the bandgap is lowered, following the energy-gap law, leading to a lower PLQY for narrow-bandgap molecules. The results of experimentally determined PLQY values are included in this figure for direct comparison. Nevertheless, further numerical simulations show that the reduced λs, \(h\bar \nu_{\mathrm{v}}\) and S values of the molecules reported herein significantly suppress the rate constant for non-radiative recombination (Supplementary Fig. 4), whereas an enhanced oscillator strength f is beneficial for an increased rate constant for radiative recombination, eventually giving rise to higher PLQY values for the molecules (calculated values of 0.1–10% for bandgaps ranging from 1.1 to 1.3 eV). It is worth noting that the PLQY values of Y11, IDSe-4Cl and COTIC-4F in dilute solutions are measured to be 17.3%, 3.26% and 3.28%, respectively, which show a noticeable increase along with their broadened energy gap, which is also predicted by the proposed model (Supplementary Fig. 5). These results demonstrate that aggregation of the studied molecules in films plays a role in reducing their emissive efficiencies. Interestingly, the extent of decrease in PLQY for the three molecules is very different, which is related to their molecular packing in the films. As demonstrated in previous investigations, the aggregation effect on the emissive efficiency is impacted by several potential factors22 (for example, a reduction of the effective reorganization energy due to exciton delocalization, or the suppression of non-adiabatic electron–vibration coupling).

Under these circumstances, A–D–A molecules with conjugation extension44 and/or enhanced planarity and rigidity in their π-conjugated backbones45, as well as increased non-bonding interactions between molecular fragments that enable reduced reorganization energies, are indeed ideal candidates that are capable of enhancing the long-wavelength emission and the emission efficiency simultaneously. To make further improvements in the PLQY, other approaches, such as heavy-atom substitution (for example, selenium substitution, as introduced in our IDSe-series molecules) or halogenation for retarding high-frequency vibration modes, could be an effective molecular-design strategy to lower the mean phonon energy \(h\bar \nu_{\mathrm{v}}\) in A–D–A molecules, as discussed below.

Although the knr values for the series of A–D–A-type organic semiconductors extracted from experimentally determined PLQY (Supplementary Table 1) and time-resolved PL decay transients (Supplementary Fig. 6) increase with decreasing bandgap, this is much less pronounced compared with the prediction of the energy-gap law (Fig. 3a). In addition, the extracted kr data show a striking increase with increasing oscillator strength (Fig. 3b), which is consistent with the model calculations (Supplementary Fig. 4g). The features shown in Fig. 3a,b ultimately translate into calculated PLQY values for all emitters, which are shown in Fig. 3c along with the measured values included for comparison. Consistent with the results obtained from photophysical studies (Fig. 2g), appropriate vibrational couplings between relevant states (that is, the overlap between the transitioning vibrational states) and superior photophysical properties (that is, the oscillator strength) can partially counteract the effect of the energy-gap law. This modelling study rationalizes and fundamentally explains why a narrow-bandgap emitter can exhibit a noticeably higher PLQY compared with a wider-bandgap emitter (Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Note 3). Furthermore, model calculations show that reducing \(h\bar \nu_{\mathrm{v}}\) by 0.02 eV or lowering S by 0.3 correspond to nearly an order of magnitude enhancement in PLQY, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 4i,j.

a–c, Rate constants of non-radiative recombination knr (a) and radiative recombination kr (b) for solid films and PLQY (c) as a function of the optical bandgap with respect to variation in the oscillator strength f (electronic coupling Vc), low-frequency reorganization energy λs and mean phonon energy \(h\bar \nu _{\mathrm{v}}\) while the electron–phonon coupling factor S is fixed at 0.8. The electronic coupling Vc is related to f via the generalized Mulliken–Hush method41,43. The symbols denote data points for non-radiative and radiative recombination rate constants extracted from analysis of the time-resolved PL measurements and PLQY values for a set of representative A-D-A-type molecules and a fullerene derivative as \(k_{{{{\mathrm{nr}}}}} = \frac{1}{\tau } - k_{\mathrm{r}}\) and \(k_{{{\mathrm{r}}}} = \frac{{{\mathrm{PLQY}}}}{\tau }\). The chemical structure of the molecules are included in the Supplementary Information. The symbols and error bars represent the mean value ± one standard deviation across six measurements for each emitter (Supplementary Table 1). The PLQY measurements were carried out under ambient conditions.

Device characterization and demonstrations

The analyses above suggest that A–D–A-type organic semiconductors show good potential for realizing high-performance SWIR OLEDs. To validate our findings, we fabricated electroluminescent devices using narrow-bandgap molecules as emitters, including Y11, IDSe-4Cl and COTIC-4F and other representative narrow-bandgap A–D–A-type molecules (with the chemical structures and the corresponding absorption spectra shown in Supplementary Figs. 7 and 8, respectively). The device architecture employed was ITO/PEDOT:PSS/emissive layer/PDINO/Ag (ITO, indium tin oxide; PEDOT:PSS, poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) polystyrene sulfonate; PDINO, (N,N-dimethylammonium N-oxide)propyl perylene diimide; Ag, silver). The OLED performance characteristics, including current density–radiance–voltage (J–R–V), EL spectra and EQE dependence on the current density (EQE–J), are shown in Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 9, while the key parameters are summarized in Table 1. The influence of doping on the EL properties was also investigated in OLEDs based on an emitting layer containing a typical host material blended with the SWIR emitters at various doping concentrations, with the device characteristics of the optimized COTIC-4F and IDSe-4Cl devices shown in Supplementary Fig. 10 and the corresponding device parameters summarized in Supplementary Table 2. The EL spectra of the COTIC-4F devices undergo a remarkable blueshift upon doping, with peaks at 1,200 nm for the COTIC-4F neat film, 1,060 nm for the 70 wt% film, 1,030 nm for the 50 wt% film and 1,010 nm for the 30 wt% film, where a similar trend is also observed in the IDSe-4Cl devices. The blueshift in the EL spectra can be attributed to the polar surrounding effect that leads to a gradual decrease in the surrounding polarity with a decreasing doping concentration of emitters with good planarity29. It is noteworthy that the maximal EQE for the doped COTIC-4F device is 0.059%, which is approximately twice that of the best non-doped COTIC-4F device (0.031%), while the doped IDSe-4Cl devices show a decreased EQE of 0.079% compared with the that for non-doped device (0.13%), which is probably as a result of the different variation of charge-transport properties between the emitting layers, as evidenced by the change in the turn-on voltage Von (Supplementary Table 2). The EL spectra of the devices demonstrate tuning with the peak ranging from 810 to 1,230 nm (Fig. 4a).

a–c, Normalized EL spectra of NIR/SWIR emission (a), and current density–radiance–voltage (J–R–V) characteristics (b) and EQE versus current density curves (c) of the SWIR OLEDs. EL spectra for devices with emission peaks between 700 nm and 1,000 nm were recorded using a spectrometer-calibrated silicon detector. EL spectra for devices with emission peaks past 1,000 nm were recorded using a spectrometer equipped with calibrated InGaAs line detector. d, Photograph of a 15 × 15 mm IDSe-4Cl OLED at a current density of 22 mA cm−2, taken using an InGaAs camera.

It is worth noting that OLEDs based on i-IDSe-4Cl (with an emission peak at 843 nm) and Y11 (a peak at 945 nm) show a maximum EQE of 0.54% and 0.33%, respectively (Table 1), which are among the highest efficiencies reported in fluorescent NIR OLEDs29. Moreover, these devices exhibit a high maximum radiant exitance of 8–14 mW cm−2, which is twice that of the best fluorescent emitter29 and comparable to state-of-the-art phosphorescent NIR OLEDs with similar EL spectra (Supplementary Fig. 11)22. More importantly, the broad tunability of the A–D–A-type organic semiconductors has enabled bright SWIR EL that spans 1,000 to 1,300 nm and beyond, which is extremely rare in organic material systems. Among them, devices based on IDSe-4F and IDSe-4Cl show the best performance (Table 1), which have EQE values of 0.12% and 0.13% with EL peaks at 1,080 nm and 1,110 nm, respectively. These two molecules are analogues of the reported ultranarrow-bandgap A–D–A-type conjugated molecules46 in which indacenodiselenophene (IDSe) is used as the electron-donating core to achieve redshifted absorption and large extinction coefficients47. Besides, a long branched alkoxy group was introduced to the inserted thiophene unit to provide good solubility for improved film quality in OLEDs. It is important to note that the EQE values of IDSe-4F and IDSe-4Cl are sevenfold higher than that of their molecular analogue TTT-C20-4F (~0.017%, Table 1), highlighting the importance of retarding the high-frequency vibration modes through heavy-atom substitution.

The superior device performance is also evident in the current density–radiance–voltage (J–R–V) characteristics, as shown in Fig. 4b, where the current density and radiance values increase exponentially by orders of magnitude after turn-on, reaching very high radiances of 12.2 W sr−1 m−2 at 3.6 V in the IDSe-4F device and 12.4 W sr−1 m−2 at 4.2 V in the IDSe-4Cl device. These encouraging radiance values correspond to a high radiant exitance (irradiance) of 3.8–3.9 mW cm−2 (corresponding to a 0.07 Sun direct sunlight infrared irradiance that is 51 mW cm−2), which is a dramatic enhancement of 60-fold compared with the best reported organic emitter with similar EL spectra3 and the brightest SWIR OLEDs so far (Supplementary Table 3 and Supplementary Fig. 11). Interestingly, the turn-on voltage (Von, the voltage at which a radiance of 1 mW sr−1 m−2 is detected) of the IDSe-4F and IDSe-4Cl devices is as low as 1.02 ± 0.076 V and 0.95 ± 0.055 V, respectively, which is essentially below the nominal emitted photon voltage (~1.1 V, defined as Vph = hν/e, where hν is the emitted photon energy, e is the elemental charge). The EL emission at subgap voltages is also observed in other A–D–A-type NIR/SWIR emitters (Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 9), among which the COTIC-4F device achieved a Von of 0.78 ± 0.041 V, which is obviously lower than the Vph of 1.14 V and is the lowest reported one in the whole OLED field so far.

Owing to thermodynamic constraints, EL emission at voltages below the emitted photon energy is hardly ever accessible but can occur without violating the energy-conservation law through the recombination of diffusion-driven and thermally generated charge carriers48. Under any voltage above 0 V, a diffusion current due to the gradient of the carrier concentrations starts to flow, following an exponential dependence on the applied voltage. According to the mechanism, it was demonstrated that once charge recombination is dominated by the diffusion of charge carriers, rather than by the drift current, while the accumulation of majority carriers takes place at the same time, emissive Langevin recombination can become apparent even when at subgap voltages. In our devices, barrier-free hole injection into the emissive layer leads to hole accumulation at the active layer/cathode interface, while a relatively small built-in potential gives rise to the establishment of a positive drift current at low forward bias (Supplementary Fig. 12). It is equally important to note that the recombination rate kRec in the diffusion-dominated regime is inversely proportional to an exponential dependence on the bandgap48 via \(k_{\mathrm{Rec}}\,=\,\gamma N_{\mathrm{C}}^{2}{\mathrm{exp}}^{ - \frac{{E_{\mathrm{g}}}}{{k_{\mathrm{B}}T}}}\left( {{\mathrm{exp}}^{\frac{{eV}}{{k_{\mathrm{B}}T}}} - 1} \right)\), where γ is the bimolecular recombination coefficient and NC is the the effective density of states in the conduction band. Therefore, the recombination rate in our low-bandgap devices is sufficiently high to fulfil the condition for diffusion-dominated recombination to occur, leading to the EL emission at subgap voltages. The conclusion of diffusion-dominated current in our devices is further supported by the calculated diffusion current using the Shockley equation and numerical drift-diffusion simulations (Supplementary Fig. 13a), both of which use the same set of extracted charge mobility data as input parameters (Supplementary Fig. 13b–d). With the validation of the diffusion-dominated current description, the bandgap of the emitters contributes to the exponential part of the current while their charge-transport properties contribute to the linear part of the current.

It is noteworthy that all devices can operate up to a high current density of 2,000–3,000 mA cm−2 (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. 9), which was challenging to realize in previous NIR/SWIR OLEDs. The detailed physical picture that leads to such a high current density tolerance is far from clear; however, it is likely to stem from the short exciton lifetime of the emitters29 (55–600 ps, Supplementary Table 1), which are beneficial for preventing the accumulation of formed excitons and thus alleviating their concomitant loss, such as via Auger recombination and exciton–exciton annihilation at high carrier injection. Moreover, our non-doped devices promise sufficient recombination sites where injected carriers can recombine, thus avoiding saturation at low current density. In addition, the driving voltage values for the high current density (for example, 1,000 mA cm−2) in our devices are extremely low (2.2 V for SiOTIC-4F/COTIC-4F, 3.2 V for Y11/Y6 and 3.0 V for IDSe-4F/IDSe-4Cl devices, see Supplementary Fig. 9j,f and Fig. 4b, respectively), which generate smaller Joule heating when compared with other reported OLEDs and thus sufficiently decrease additional exciton dissociation. Moreover, this high current density corresponds to a carrier density of around 1018 cm−3, which is a threshold for lasing under electrical excitation49. Interestingly, with increasing current density, the EQE values for all devices except those based on larger bandgap materials (for example, Y11 and i-IDSe-4Cl) demonstrate a remarkable increase, which ultimately gives rise to a high SWIR radiance. This dependence of EQE on current density is particularly striking as it implies that radiative recombination can compete with non-radiative recombination at high current densities in the OLEDs. One possible interpretation for this unusual dependency is that it corresponds to a trap-filling process with increasing voltage that not only shifts the recombination zone away from the electrode but also eliminates the non-radiative trap-assisted recombination, leading to an EQE enhancement of more than a factor of two in most devices. The injection-dependent EL spectra shown in Supplementary Fig. 14 are consistent with a recent study by Blom and colleagues, who reported that a voltage-dependent EL is a fingerprint of trap-assisted recombination50, and thus confirms the interpretation that radiative recombination dominates over competing trap-assisted recombination with increasing current density. In this manner, the A–D–A-type organic semiconductors possess the potential to fundamentally overcome the SWIR lasing boundary set by the high-excitation-threshold requirement and efficiency roll-off at high current density.

To demonstrate the potential of our technology, we fabricated large-area SWIR OLEDs based on IDSe-4Cl/IDSe-4F. Figure 4d shows a photograph of a typical IDSe-4Cl device with a peak emission wavelength at 1,110 nm and a SWIR radiation power of ∼0.6 mW at a current density of 22 mA cm−2, which shows a remarkable emission uniformity over the substrate area with a size of 15 × 15 mm. The large-area device possesses a high maximum SWIR output power of ~8.8 mW, which is comparable to 10 mW as seen for InGaAs-based LEDs. These results demonstrate the promise of our devices as a cost-efficient flat-panel light source for applications in portable spectrometers, information-secured displays and night-vision target identification. To provide visualization for these applications, we set up an optical wireless communication system (see Methods for the setup and Supplementary Fig. 15 for the simplified block diagram) in which our SWIR OLEDs are integrated as the transmitter for a free-space data link. Transmitting audio signals or pulsed signals is achieved through the modulation of infrared light, while an InGaAs photodiode was used as the receiver for audio signal recovery. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 15, there is no obvious distortion in the received signals, indicating that our system provides sufficient transmission capacity. Owing to the bright radiance and the fast switching ability, the application of our SWIR OLEDs makes light-fidelity (or Li-Fi) communication possible and more flexible. We further demonstrate the real-time transmission of audio signals and pulsed signals through biological tissue (for example, meat or fish slices) (Supplementary Videos 1 and 2). We further demonstrate that SWIR OLEDs held great promise for the inspection of semiconductor wafer and chip quality. Since the absorption edge is ~1,100 nm for multi-crystalline silicon and ~1,050 nm for single-crystalline silicon, our IDSe-4Cl device is more advantageous in that its emission is peak located at 1,110 nm compared with a visible-light source. Indeed, as shown in Fig. 5a,b, the SWIR light source shows considerable optical transmission, whereas the wafer is opaque to the visible-light source. The emission from the IDSe-4Cl OLEDs can penetrate the wafer when illuminated from below and reveal more details, making these OLEDs ideal for industrial applications, such as in the detection of pinholes and cracks in wafers. Snapshot images of the microchip yielded by SWIR irradiance from our devices are shown in Fig. 5c, with the images obtained from visible-light illumination included in Fig. 5d for comparison. The features of the microcircuit and details of defects or cracks can be clearly observed in the SWIR image, whereas part of visible-light image is obscure. In addition, the Y11 device exhibits good operation stability, and shows a half-life operation lifetime (T50, the time taken for the radiance to decay to half its initial value) of at least 1,000 h (Supplementary Fig. 16) at a high current density of 100 mA cm−2 when evaluated under continuous operating conditions and in a glovebox with encapsulation. Other devices based on the IDSe-4F, IDSe-4Cl and COTIC-4F emitters also show comparable lifetime values of 1,000 h (Supplementary Fig. 16a). It is worthy of note that the COTIC-4F device shows a longer T50 of over 500 h when tested in air compared with 300–400 h for other emitters. These findings on large-area devices with high brightness and good stability open up a pathway toward low-cost, portable SWIR OLED light sources for emerging applications.

a,b, Images of a single-sided polished silicon wafer (~250 µm thickness) obtained under irradiation of the IDSe-4Cl device (a) and a visible-light source (b). In a, the top inset shows an image of the wafer on top of the SWIR light source at a lower magnification and the bottom inset shows an image at a higher magnification, in which the SWIR emission from below penetrates the whole wafer. All SWIR images are taken under transmission mode, and visible images are taken in a reflection mode. In b, the bottom inset shows an image at a lower magnification. c,d, Images of a microchip taken under irradiation of the IDSe-4Cl device (c) and a visible-light source (d). In c, the top inset shows an image of the chip at a lower magnification. Microcircuit areas are highlighted in areas marked (i) and (ii), and a defect/crack is identified in (iii).

Conclusion

In summary, we demonstrate OLEDs with bright SWIR emission using finely tuned A–D–A-type molecules as emitters. The resultant OLEDs exhibited very favourable device performance values, including a notable radiance and efficiency in the SWIR region, a very low turn-on voltage at subgap voltages and an even higher efficiency at a high current density of the order of around amperes per cm2. We found that the impressive performance of these SWIR OLEDs is essentially due to the excellent photophysical properties of the A–D–A-type molecules, in which their coplanarity, π-conjugated backbone rigidity, extremely small reorganization energies and electron–phonon coupling factors, combined with the heavy-atom substitution that retards high-frequency vibration modes, contributed to significantly suppressed non-radiative recombination rates and improved PLQY values. Furthermore, given their large oscillator strength and their ability to operate at high current density, these A–D–A-type molecules hold the potential to fulfil electrically pumped SWIR lasers. Benefiting from the semi-transparency of biological tissue to SWIR radiation, their high radiation power and the absence of toxic heavy metals in their make-up, our devices provide a promising outlook for a wide range of emerging applications (Supplementary Fig. 17), such as next-generation optoelectronic devices, wearable biosensors, implantable bioelectronics, IoT (Internet of Things) connectivity and biological imaging.

Methods

Materials

The A–D–A-type molecules Y11, SiOTIC-4F and COTIC-4F were obtained as commercial chemicals from 1-Material, and Y6 and BTA3 were purchased from Solarmer. The three twisted small molecules i-IDSe, i-IDSe-4F, and i-IDSe-4Cl were prepared using a synthetic route employed in ref. 51. Perylene diimide functionalized with amino N-oxide (PDINO) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. PEDOT:PSS in aqueous solution was purchased from H.C. Starck. All purchased chemicals were used as received without additional purification. Unless otherwise stated, all other A–D–A-type molecules were synthesized in the laboratory using a route described in the Supplementary Methods.

Computational methods

To study the electronic-structure properties of the molecules Y11, IDSe-4Cl and COTIC-4F (discussed in the main text), we carried out quantum-chemical calculations on them. In our calculations, all the long alkyl chains attached to their π-conjugated backbones were replaced by methyl groups, which is a standard procedure for studying electronic structures of single molecules. Molecular aggregation definitely impacts the electronic and optical properties in solid-state films22. Many studies have demonstrated that long alkyl chains significantly impact the aggregation structures of the molecules52,53, similar to what is observed in the present work. The initial geometries of these three molecules were optimized using the range-separated functional ωB97XD (with a default range-separation parameter ω of 0.2 bohr−1) and the 6-31G(d,p) basis set. An iteration procedure28,54 was used to non-empirically tune the ω parameter with the implicit consideration of the dielectric environment via the polarizable continuum model; the dielectric constant ε was chosen to be 4.5, which is a representative value for non-polar organic semiconductor materials. The TD-DFT approach was used to study the excited-state properties. All quantum-chemical calculations were performed using the Gaussian 16 Rev A03 program55. The overlaps between the NTO electron and hole wavefunctions describing the S1 excited states were quantified using the Multiwfn program56.

Optical absorption and photoluminescence characterization

The absorption spectra of the solid-state films were measured using an ultraviolet-visible-NIR spectrophotometer (UV3600, Shimadzu). For measurement of the steady-state PL of solid films, semiconductor lasers were used for excitation, where the wavelength was 530 nm (for PC71BM), 635 nm (for BTA3, ITIC, IT-M, IT-4F and i-IEICO-4F) or 852 nm (for Y6, Y11, IDSe-Th, IDSe-4F and IDSe-4Cl, SiOTIC-4F and COTIC-4F). To measure the PL from solutions, a 635 nm laser was employed to excite the Y11 solution, and an 852 nm laser was used for IDSe-4Cl and COTIC-4F excitation. Calibrated spectrometers (QE Pro and NIR Quest 512, Ocean Optics), which were equipped with a cooled Hamamatsu CCD (charge-coupled device) array (−20 °C) in conjunction with an integrating sphere, severed as the spectral acquisition system. To avoid self-absorption, an integrating sphere with a diameter of 20.32 cm was used to measure the PL from solutions. To minimize the scattering of incident laser, a longpass filter with a cutoff wavelength at 750 nm or 860 nm was placed between the sample and detector. All PL experiments were carried out under ambient conditions of 25 °C.

Photoluminescence quantum yield measurements

The absolute PLQY values for emitters with an emission between 300 and 950 nm were measured using an integrating-sphere-coupled spectrometer (QE Pro) and further verified using a commercial absolute PLQY measurement system (C11347-11, Hamamatsu Photonics), while PLQY data for an emission above 950 nm were determined using an integrating sphere and a calibrated spectrometer (NIR Quest 512) as the ratio of the number of photons re-emitted to the number of photons absorbed.

Measurement of time-resolved photoluminescence spectra

The time-resolved PL spectra of the emitters were acquired under ambient conditions of 25 °C using a fluorescence lifetime spectrometer via a time-correlated single-photon-counting technique (Hydraharp 400, PicoQuant). The samples were excited using a femtosecond Ti:sapphire pulsed laser (Coherent) with a pulse duration of 120 fs, a fluence of ~0.2 μJ cm−2 per pulse and a repetition rate of 80 MHz. The PL data were collected using a single-photon-counting photomultiplier tube detector. A longpass filter with a cutoff wavelength at 715 nm or 780 nm was placed before the detector to minimize the scattering of incident laser light.

Device fabrication and characterization

Device fabrication

The devices were fabricated on patterned ITO-coated glass substrates with a sheet resistance of 15–20 ohm per square. The ITO substrates had previously undergone wet-cleaning process in an ultrasonic bath, beginning with acetone, followed by deionized water and isopropanol, before finally being dried in an oven overnight. After air-plasma treatment, a 40-nm-thick PEDOT:PSS (PEDOT:PSS 4083) anode buffer layer was spin-cast onto the precleaned ITO substrate then dried by baking at 150 °C for 20 min. Subsequently, the luminescent small-molecule films (COTIC-4F, IDSe-4Cl, Y11 and so on) were prepared by spin-coating their chloroform solution (with a concentration of 20 mg ml−1) at 2,000 revolutions per minute for 30 s to form a uniform 100-nm-thick film on the top of the anode buffer layer. Then a 10-nm-thick PDINO layer was deposited onto the emitting layer by spin-coating from methanol solution (with a concentration of 1.5 mg ml−1). Finally, a 100-nm-thick silver electrode was evaporated with a shadow mask (~2 × 8 mm) in a vacuum chamber at a pressure of 1 × 10−4 Pa. All device-fabrication processes, except for spin-coating of the PEDOT:PSS layer, were carried out in a nitrogen-filled glovebox (O2 < 1 ppm, H2O < 1 ppm) without exposure to air. We fabricated devices for each emitter at least four times under similar conditions and evaluated at least 15 devices for each emitter reported. Before measurements, the fabricated devices were encapsulated using a glass cover plate and a UV-cured epoxy resin.

Current density–radiance–voltage characteristics and external quantum efficiency measurements

The current density–voltage characteristics of the devices were measured using a Keithley 238 source-meter unit while the radiance–voltage characteristics were simultaneously recorded using a silicon photodiode. The radiance of the SWIR OLEDs was measured by collecting all forward-viewing photons from the device without taking the waveguide modes into account through a lens connected to an integrating sphere. The radiance was calibrated using spectrometers (QE Pro and NIR Quest 512). The InGaAs detector of the spectrometer was calibrated from 900 nm to 1,700 nm using a standard halogen calibration light source (HL-3-plus-INT-CAL), whose wavelength of irradiance ranges from 350 nm to 2,400 nm. The EQE was calculated by dividing the number of photons extracted by the number of electrons injected, per unit time. In the EQE measurements, the number of emitted photons was calculated from the radiance and emission wavelength.

Electroluminescence spectroscopy measurements

The EL spectra for devices with emission peaks between 700 nm and 1,000 nm were recorded using a spectrometer (QE Pro) with a calibrated silicon photodetector. EL spectra for devices with emission peaks past 1,000 nm were recorded using a spectrometer (NIR Quest 512) equipped with an InGaAs line photodetector (calibrated from 900 nm to 1,700 nm).

Operational lifetime measurements

Before operational lifetime measurements, devices were stored in a nitrogen-filled glovebox in the dark. The operational lifetime of the devices was recorded using a commercial system (Life Tester-College Edition, Guangzhou Crysco Equipment) that was equipped with a programmable direct-current power supply (HMC8200) and multiple silicon photodetectors (PDB-C613-2, Lunainc Photonics), where the initial radiant exitance was calibrated using a spectrometer (NIR Quest 512).

Optical wireless communication system setup

A transistor (model S9013) was used to obtain audio signal amplification and drive the SWIR OLEDs with an active area of 0.16 cm2 for analogue audio signal transmission. At the receiver end, a high-sensitivity InGaAs photodetector (MTPD1346D-300) was used to convert radiation into photocurrent, which was transmitted to a speaker through a low-voltage audio power amplifier (LM386). For transmission of the pulsed signal, the signal was produced using a function generator (AFG3102C, Tektronix), and the transmitted and received signals were displayed using an oscilloscope (MDO3024, Tektronix) via two independent channels.

SWIR photographs and videos

Photographs and videos of the SWIR light source were obtained using a SWIR camera (LD-SW6401725-CTE2-G (Leading Optoelectronic) or ARTCAM-032 (Artray)) whose detection range was between 950 nm and 1,700 nm with a pixel resolution of 25 μm. Microscopic photographs were taken using a transflective polarizing microscope (XP4A, SHMLT) equipped with a visible-light CCD, and the SWIR photographs were recorded by switching the self-equipped CCD to the SWIR camera.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Tang, C. W. & VanSlyke, S. A. Organic electroluminescent diodes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 51, 913–915 (1987).

Burroughes, J. H. et al. Light-emitting diodes based on conjugated polymers. Nature 347, 539–541 (1990).

Qian, G. et al. Simple and efficient near-infrared organic chromophores for light-emitting diodes with single electroluminescent emission above 1000 nm. Adv. Mater. 21, 111–116 (2009).

Zampetti, A., Minotto, A. & Cacialli, F. Near-infrared (NIR) organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs): challenges and opportunities. Adv. Func. Mater. 29, 1807623 (2019).

Zheng, Y. & Zhu, X. Recent progress in emerging near-infrared emitting materials for light-emitting diode applications. Org. Mater. 2, 253–281 (2020).

Konstantatos, G. et al. Ultrasensitive solution-cast quantum dot photodetectors. Nature 442, 180–183 (2006).

Lu, H., Carroll, G. M., Neale, N. R. & Beard, M. C. Infrared quantum dots: progress, challenges, and opportunities. ACS Nano 13, 939–953 (2019).

Murphy, C. J. Optical sensing with quantum dots. Anal. Chem. 74, 520A–526A (2002).

Smith, A. M., Mancini, M. C. & Nie, S. Second window for in vivo imaging. Nat. Nanotechnol. 4, 710–711 (2009).

Wilson, R. H., Nadeau, K. P., Jaworski, F. B., Tromberg, B. J. & Durkin, A. J. Review of short-wave infrared spectroscopy and imaging methods for biological tissue characterization. J. Biomed. Opt. 20, 030901 (2015).

Diao, S. et al. Fluorescence imaging in vivo at wavelengths beyond 1,500 nm. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 14758–14762 (2015).

Bruns, O. T. et al. Next-generation in vivo optical imaging with short-wave infrared quantum dots. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 1, 0056 (2017).

Minotto, A. et al. Towards efficient near-infrared fluorescent organic light-emitting diodes. Light Sci. Appl. 10, 18–27 (2021).

Wu, J. When group-III nitrides go infrared: new properties and perspectives. J. Appl. Phys. 106, 011101 (2009).

Krier, A., Chub, D., Krier, S. E., Hopkinson, M. & Hill, G. Light sources for wavelengths >2 μm grown by MBE on InP using a strain relaxed buffer. IEE Proc. Optoelectron. 145, 292–296 (1998).

Someya, T., Bao, Z. & Malliaras, G. The rise of plastic bioelectronics. Nature 540, 379–385 (2016).

Tessler, N., Medvedev, V., Kazes, M., Kan, S. & Banin, U. Efficient near-infrared polymer nanocrystal light-emitting diodes. Science 295, 1506–1508 (2002).

Qi, J., Qiao, W. & Wang, Z. Y. Advances in organic near-infrared materials and emerging applications. Chem. Rec. 16, 1531–1548 (2016).

Ho, C. L., Li, H. & Wong, W. Y. Red to near-infrared organometallic phosphorescent dyes for OLED applications. J. Organomet. Chem. 751, 261–285 (2014).

Ai, X. et al. Efficient radical-based light-emitting diodes with doublet emission. Nature 563, 536–540 (2018).

Tao, R. et al. High-efficiency near-infrared organic light-emitting devices based on an iridium complex with negligible efficiency roll-off. J. Mater. Chem. C 1, 6446–6454 (2013).

Wei, Y. C. et al. Overcoming the energy gap law in near-infrared OLEDs by exciton–vibration decoupling. Nat. Photonics 14, 570–577 (2020).

Suzuki, H. Infrared electroluminescence from an organic ionic dye containing no rare-earth ions. Appl. Phys. Lett. 80, 3256–3258 (2002).

Chen, M. et al. 1 micron wavelength photo- and electroluminescence from a conjugated polymer. Appl. Phys. Lett. 84, 3570–3572 (2004).

Minotto, A. et al. Efficient near-infrared electroluminescence at 840 nm with “metal-free” small-molecule:polymer blends. Adv. Mater. 30, 1706584 (2018).

Qian, G. et al. Band gap tunable, donor–acceptor–donor charge-transfer heteroquinoid-based chromophores: near infrared photoluminescence and electroluminescence. Chem. Mater. 20, 6208–6216 (2008).

Yao, L. et al. Highly efficient near-infrared organic light-emitting diode based on a butterfly-shaped donor–acceptor chromophore with strong solid-state fluorescence and a large proportion of radiative excitons. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 2119–2123 (2014).

Kim, D. H. et al. High efficiency electroluminescence and amplified spontaneous emission from a thermally activated delayed fluorescent near-infrared emitter. Nat. Photonics 12, 98–104 (2018).

Yu, Y. et al. Near-infrared electroluminescence beyond 800 nm with high efficiency and radiance from anthracene cored emitters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 21578–21584 (2020).

Tregnago, G., Steckler, T. T., Fenwick, O., Andersson, M. R. & Cacialli, F. Thia- and selenadiazole containing polymers for near-infrared light-emitting diodes. J. Mater. Chem. C 3, 2792–2797 (2015).

Lin, Y. et al. An electron acceptor challenging fullerenes for efficient polymer solar cells. Adv. Mater. 27, 1170–1174 (2015).

Liu, S. et al. High-efficiency organic solar cells with low non-radiative recombination loss and low energetic disorder. Nat. Photonics 14, 300–305 (2020).

Rau, U. Reciprocity relation between photovoltaic quantum efficiency and electroluminescent emission of solar cells. Phys. Rev. B 76, 085303 (2007).

Lee, J. et al. Bandgap narrowing in non-fullerene acceptors: single atom substitution leads to high optoelectronic response beyond 1000 nm. Adv. Energy Mater. 8, 1801212 (2018).

Roncali, J. Molecular engineering of the band gap of π-conjugated systems: facing technological applications. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 28, 1761–1775 (2007).

Shuai, Z. G. & Peng, Q. Organic light-emitting diodes: theoretical understanding of highly efficient materials and development of computational methodology. Natl Sci. Rev. 4, 224–239 (2017).

Benduhn, J. et al. Intrinsic non-radiative voltage losses in fullerene-based organic solar cells. Nat. Energy 2, 17053 (2017).

Perdigón-Toro, L. et al. Excitons dominate the emission from PM6:Y6 solar cells, but this does not help the open-circuit voltage of the device. ACS Energy Lett. 6, 557–564 (2021).

Jortner, J. Temperature dependent activation energy for electron transfer between biological molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 64, 4860–4867 (1976).

Gould, I. R. et al. Radiative and nonradiative electron transfer in contact radical-ion pairs. Chem. Phys. 176, 439–456 (1993).

Azzouzi, M. et al. Nonradiative energy losses in bulk-heterojunction organic photovoltaics. Phys. Rev. X 8, 031055 (2018).

Wilson, J. S. et al. The energy gap law for triplet states in Pt-containing conjugated polymers and monomers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 9412–9417 (2001).

Cave, R. J. & Newton, M. D. Generalization of the Mulliken–Hush treatment for the calculation of electron transfer matrix elements. Chem. Phys. Lett. 249, 15–19 (1996).

Zhu, W. et al. Crystallography, morphology, electronic structure, and transport in non-fullerene/non-Indacenodithienothiophene polymer: Y6 solar cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 14532–14547 (2020).

Zhang, G. et al. Delocalization of exciton and electron wavefunction in non-fullerene acceptor molecules enables efficient organic solar cells. Nat. Commun. 11, 3943 (2020).

Yao, H. et al. Design, synthesis, and photovoltaic characterization of a small molecular acceptor with an ultra-narrow band gap. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 3045–3049 (2017).

Intemann, J. J. et al. Molecular weight effect on the absorption, charge carrier mobility, and photovoltaic performance of an indacenodiselenophene-based ladder-type polymer. Chem. Mater. 25, 3188–3195 (2013).

Li, Y. et al. Universal electroluminescence at voltages below the energy gap in organic light-emitting diodes. Adv. Optical Mater. 8, 2101149 (2021).

Liu, X. K. et al. Metal halide perovskites for light-emitting diodes. Nat. Mater. 20, 10–21 (2021).

Kuik, M. et al. 25th Anniversary Article: Charge transport and recombination in polymer light-emitting diodes. Adv. Mater. 26, 512–531 (2014).

Wang, W. et al. Achieving efficient polymer solar cells based on near-infrared absorptive backbone twisted non-fullerene acceptors through a synergistic strategy of indacenodiselenophene fused-ring core and chlorinated terminal group. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 5, 1322–1330 (2022).

Li, C. et al. Non-fullerene acceptors with branched side chains and improved molecular packing to exceed 18% efficiency in organic solar cells. Nat. Energy 6, 605–613 (2021).

Jiang, K. et al. Alkyl chain tuning of small molecule acceptors for efficient organic solar cells. Joule 3, 3020–3033 (2019).

Cui, L.-S. et al. Fast spin-flip enables efficient and stable organic electroluminescence from charge-transfer states. Nat. Photonics 14, 636–642 (2020).

Frisch, M. J. et al. Gaussian 16 revision C.01 (Gaussian, Inc., 2016).

Lu, T. & Chen, F. Multiwfn: a multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 33, 580–592 (2012).

Acknowledgements

Hongbin Wu thanks the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 52273177, 91333206 and 51521002) for financial support. Y.X. acknowledges the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 52003087) for financial support. C.G. thanks the Shaanxi Key Scientific and Technological Innovation Team Project (no. 2016KCT-28) and Shaanxi Key Project in Industrial Field (no. 2017ZDXM-GY-046) for financial support. W.D. acknowledges support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 62004069). X.-K.C. acknowledges the New Faculty Start-up Grant of the City University of Hong Kong (7200709 and 9610547). We thank D. Li for assistance with the OLED operational lifetime measurements.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.X., Hongbin Wu and C.G. conceived the idea. Y.X. and W.L. fabricated the SWIR OLEDs devices. C.G., Haimei Wu and W.W. designed and synthesized the i-IDSe- and IDSe-series A–D–A-type emitters. Y.X. performed the theoretical calculations and the numerical simulations. X.-K.C. performed the theoretical calculations and provided feedback on the manuscript. Y.X., W.L. and W.D. performed the device characterization and optical absorption measurements. W.D. and W.L. performed the time-resolved PL decay measurements. Y.X. and W.D. performed the recombination-rate calculations. W.L. and Y.X. acquired the SWIR EL photographs. Y.S. set up the optical communication system. W.L. and Y.X. carried out optical communication demonstration, wafer-quality inspection and operational lifetime tests. X.Z. and J.P. discussed the results and commented on the manuscript. Hongbin Wu, Y.X., C.G., W.D., W.L. and X.-K.C. contributed to the writing of the manuscript. All authors discussed the experiments and results. Hongbin Wu, C.G. and Y.C. supervised the project and advised on device optimization.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Photonics thanks Juan Qiao, Xiaozhang Zhu and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–17, Notes 1–3, Tables 1–3 and Methods.

Supplementary Video 1

Demonstration of real-time through-biological-tissue audio signals transmission.

Supplementary Video 2

Demonstration of pulsed signals transmission.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data for Fig. 1d and the source data of the output of Gaussian 16 (ES64L-G16RevC.01).

Source Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data for the absorption and PL spectra of the emitters, normalized reduced emission spectra and modelled PLQYs.

Source Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data for the measured and calculated rate constants for radiative and non-radiative recombination and the PLQY of each emitter.

Source Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data for EL spectra, J–R–V characteristics and EQE–J curves of SWIR OLEDs.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Xie, Y., Liu, W., Deng, W. et al. Bright short-wavelength infrared organic light-emitting devices. Nat. Photon. 16, 752–761 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-022-01069-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-022-01069-w

This article is cited by

-

Alleviating NIR-II emission quenching in ring-fused fluorophore via manipulating dimer populations for superior fluorescence imaging

Light: Science & Applications (2025)

-

Ultrahigh-radiance near-infrared organic light-emitting diodes

Nature Photonics (2025)

-

Triplets electrically turn on insulating lanthanide-doped nanoparticles

Nature (2025)

-

A stable and biocompatible shortwave infrared nanoribbon for dual-channel in vivo imaging

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Blue organic long-persistent luminescence via upconversion from charge-transfer to locally excited singlet state

Nature Communications (2025)