Abstract

The remarkable frequency stability of resonant systems in the optical domain (optical cavities and atomic transitions) can be harnessed at frequency scales accessible by electronics using optical frequency division. This capability is revolutionizing technologies spanning time keeping to high-performance electrical signal sources. A version of the technique called two-point optical frequency division (2P-OFD) is proving advantageous for application to high-performance signal sources. In 2P-OFD, an optical cavity anchors two spectral endpoints defined by lines of a frequency comb. The comb need not be self-referenced, which greatly simplifies the system architecture and reduces power requirements. Here, a 2P-OFD microwave signal source is demonstrated with record-low phase noise using a microcomb. Key to this advance is a spectral endpoint defined by a frequency-agile single-mode dispersive wave that is emitted by the microcomb soliton. Moreover, the system frequency reference is a compact all-solid-state optical cavity with a record Q factor. A hybridly packaged version of the system offers excellent longer term stability. The results advance integrable microcomb-based signal sources into the performance realm of much larger microwave sources.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

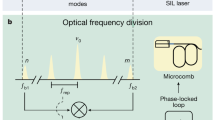

An octave spanning frequency comb is required to perform conventional optical frequency division, wherein the maximum frequency division ratio is attained as, for example, is required to count optical cycles1. This method has led to the most stable microwave signals ever generated2,3,4. Two-point optical frequency division (2P-OFD) trades-off a portion of this performance for technical simplification resulting from using a non-self-referenced (narrower spectral span) frequency comb5,6. This tradeoff has made possible compact commercial microwave systems based on electro-optically generated combs7,8 and chip-integrable microwave signal sources using microcombs9,10,11,12,13. In microcomb-based 2P-OFD, spectral endpoints of the comb are locked to two frequencies of a reference cavity. This transfers relative frequency stability from the cavity to the comb repetition rate, which can be photodetected to generate a microwave signal. Control of power and frequency at the comb spectral endpoints is critically important to 2P-OFD. High power at these endpoints is necessary for low phase noise microwave signal generation, and endpoint frequency control is essential to roughly align these frequencies with reference laser lines. This combination of features is challenging in bright soliton microcombs, which also offer the highest frequency division performance through their broad spectral reach. Here, 2P-OFD is demonstrated using a bright soliton microcomb with spectral endpoints that are both high in power and frequency tunable. These features in combination with the spectral reach of the microcomb achieve optical division noise reduction (to a detectable microwave signal) that is 30 times greater than in recent reports9. The microcomb is referenced to a solid state cavity with eight-fold higher Q-factor relative to earlier designs14, and together make possible a record-low phase noise for chip-integrable components.

High power spectral endpoints with tunable frequency control are fully achieved in electro-optic combs6 on account of their tunable repetition rate and ability to efficiently throw pump power to the comb spectral wings. High power spectral endpoints (without tuning control) is also a feature of normal dispersion microcombs15 (sometimes called dark pulse combs16) and for this reason these combs have been used recently for microwave signal generation9. There, the lack of endpoint tuning is less important when the comb repetition rate is low enough to guarantee comb line spectral proximity to the optical reference; however, both of the these comb generation methods tend to provide narrower comb spectral spans, thereby limiting the amount of optical frequency division. And although bright soliton microcombs offer broader spectral spans, their per-line comb power is limited on account of the steep (exponential) roll-off in comb spectral envelope away from the pump line17.

Dispersive wave generation provides a solution to this problem18,19 and has been implemented in optical synthesizer20 and optical clock21 demonstrations featuring octave-span microcombs and full optical frequency division. Dispersive waves form when soliton comb lines phase match to resonator modes (from either the same or another mode family). They appear as a spectrally local enhancement in comb line power near the phase matching frequency. Strong single-line dispersive waves can form in cases where a single cavity mode phase matches to the soliton22; however geometrical control of dispersion to accomplish this matching is challenging, because the actual wavelength of the dispersive wave is sensitive to fabrication variance. Tuning of this phase matching condition is possible in coupled ring resonators23. In this paper, broad tuning of single-line dispersive waves is used to implement broadband 2P-OFD at directly detectable microwave repetition rates.

2P-OFD measurement

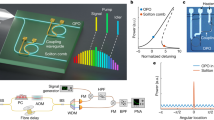

The microcomb uses a three-coupled-ring (3CR) design fabricated using ultra-low-loss silicon nitride (Fig. 1a). The resonator mode locks through formation of femtosecond pulse pairs24. As described below, differential heating of the rings allows for both broad dispersion tuning to set-up the pulse pair operation, as well as fine tuning for control of dispersive wave emission. Refer to the Methods for further details on the 3CR properties. Two lines of the microcomb (νm near the pump frequency) and νn (the dispersive wave frequency) serve as spectral endpoints for 2P-OFD (Fig. 1b). Besides the microcomb, two continuous-wave lasers are stabilized to a miniature high-finesse, vacuum-free Fabry–Pérot resonator (Fig. 1c) that provides reference frequencies ν1 and ν2, as in Fig. 1d.

a, Photograph of the 3CR resonator with heaters for differential temperature tuning of the three rings. b, Schematic of the microcomb in the 2P-OFD system. A dispersive wave at frequency νn is electrically tuned to closely match the frequency ν2 of the continuous-wave (c.w.) laser. c, Photograph of the miniature, vacuum-free Fabry–Pérot (FP) cavity with a US nickel. Inset: Fabry–Pérot cavity reflection spectrum showing Q-factor of 8.2 billion. d, Schematic of the Fabry–Pérot cavity spectrum in the 2P-OFD system, wherein two continuous-wave lasers at frequencies ν1 and ν2 (separated by approximately 3 THz) are locked to the cavity. Beatnote frequencies f1 and f2 between comb lines and the nearby continuous-wave lasers are generated via photodetection (~1 GHz), and mixed to generate their sum frequency. The summed frequency is stabilized to a local oscillator (fLO) by feedback to the microcomb. The microcomb repetition rate is given by frep = (ν2 − ν1 + fLO)/(n − m), which divides the 3 THz laser separation down to the microcomb repetition rate at microwave frequency (20 GHz). e, Detailed experimental set-up of the 2P-OFD schematic in d. EDFA, erbium-doped fibre amplifier; PD, photodetector; LO, local oscillator. f, Single-sideband (SSB) phase noise spectrum measurement with carrier frequency near 20 GHz (red). The instrumental measurement floor is the grey shaded area. For comparison, the phase noise is scaled by Lϕ,10GHz = Lϕ,frep − 20 × log10(frep/10 GHz), and plotted in black. g, High-spectral purity microwave tone near 20 GHz generated by the 2P-OFD system. The resolution bandwidth (RBW) of the measured microwave tone is 3 Hz.

The detailed experimental set-up is depicted in Fig. 1e. The microcomb is pumped at the bus waveguide coupled to the central ring in Fig. 1a, and comb power is collected at the waveguide coupled to the left ring (drop port) and amplified by an Erbium-doped fibre amplifier to 60 mW; 75% of the amplified power is split evenly and filtered by two optical bandpass filters to select two desired comb lines. These are combined with their respective stabilized continuous-wave laser, and detected by two photodetectors (New Focus 1611) to generate beatnotes at frequencies f1 and f2. The formation of the dispersive wave improves the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of this beatnote by 30 dB (Extended Data Fig. 1). This enhancement makes possible 2P-OFD over this broader comb span of 3 THz (that is, νn – νm in Fig. 1b). The two beatnote signals are electrically amplified before mixing to generate their frequency-summed signal. This signal at frequency fLO is amplified and mixed with a local oscillator at 1.25 GHz to generate the error signal. The error signal is processed by a servo (Vescent D2-125) for feedback to the microcomb to control its repetition rate (Fig. 1e). This closed loop thereby implements 2P-OFD. Additional details are provided in the caption to Fig. 1d.

Details on the Fabry–Pérot cavity are provided elsewhere14,25 (and in Methods), but briefly it is a bulk fused silica rod with high-reflectivity coatings. The free spectral range (FSR) is 4.0 GHz and cavity Q-factor is as high as 8.2 × 109 (inset of Fig. 1c). The Q-factor is improved by more than eight times compared with a previous demonstration14. The vacuum-free nature of the Fabry–Pérot cavity simplifies the operation compared with the vacuum-based reference cavities26,27,28 and its ultra-high Q-factor boosts its performance in stabilizing lasers compared with other vacuum-free reference cavities29,30,31. Upon Pound–Drever–Hall locking to the cavity, relative phase noise of the two continuous-wave lasers is −113 dBc Hz–1 at 10 kHz offset frequency, when separated by one FSR of the Fabry–Pérot cavity. This is 64 dB lower than their free-running relative noise (Extended Data Fig. 2).

For microwave generation, the remaining 25% of the amplified microcomb output is directed to a fast photodetector (U2T XPDV2320R), generating a radio frequency signal of −7 dBm at frep (near 20 GHz). The microwave phase noise is shown in Fig. 1f (measured using an R&S FSWP). When scaled to a 10 GHz carrier (black curve), the single-sideband phase noise is −101 dBc Hz–1 at 100 Hz, −133 dBc Hz–1 at 1 kHz, and −152 dBc Hz–1 at 10 kHz, which is a record-low to our knowledge among photonic-chip-based platforms9,10,11,12,32,33. Figure 1g shows a representative radio frequency tone (frep) under the 2P-OFD.

Dispersive-wave-tunable microcomb

Concerning the microresonator design, the three rings share the same waveguide cross section, but the left (right) ring B (C) is 3 × 10−3 times larger (smaller) than the middle ring (ring A). The left (B) and right (C) rings are respectively coupled to the middle ring (A) by the evanescent field of neighbouring waveguides (2.4 µm coupling gap). The Si3N4 waveguides feature normal dispersion, but mode coupling enables generation of bright pulse pairs24. These pulse pairs form in certain spectral windows that can be tuned by electrical control of the ring temperatures using the heaters in Fig. 1a. A two-step tuning protocol is described in the Extended Data Fig. 3 and Methods that allows configuration of the comb from any initial configuration. Likewise, this protocol permits higher-order dispersion control that tunes the dispersive wave wavelength. It is noted that after the differential tuning is completed, the resulting dispersion and microcomb spectrum are very stable. No change in dispersion or microcomb spectrum was observable over two months of measurements.

Upon set-up of the microcomb using this protocol, three dispersion bands are apparent as shown in Fig. 2a, where measured (blue) and modelled (black) integrated dispersion Dint (ref. 17) is plotted versus wavelength (Methods)24,34. The upper band is used for microcomb generation and is pumped near 1,565 nm. Concerning the structure of these bands, there is no simple closed-form expression for the dispersion spectrum, but there are some universal features. The dispersion spectra of the uncoupled rings are indicated by the coloured curves (red, blue and grey for the three rings, respectively). Where ring A crosses the curves of rings B and C (indicated by the two arrows), two bandgaps are opened following the introduction of ring coupling. Also note that rings B and C are able to indirectly couple to each other through their mutual interaction with ring A. This coupling creates another smaller bandgap. The magnitude of these gaps can be related to coupling strength and dispersion, and it is discussed further in the Methods.

a, Measured dispersion spectrum showing the three dispersion bands of the 3CR device (blue dots). The theoretical fitting is plotted as the solid curves, and the inferred dispersion of the uncoupled rings are the shaded lines (red, blue and grey for rings A, B and C, respectively). The relative mode number m − mo is plotted in the upper axis, where mo corresponds to the intersection of the uncoupled dispersion curves of rings B and C. The corresponding wavelength is λo = 1,568 nm (lower axis). b, Isolated dispersion spectrum for the upper band in a. Dashed horizontal line gives location of the dispersive wave (DW) phase matching wavelengths. c, Optical spectra of bright soliton microcomb showing tuning of the dispersive waves. Inset: illustration of the dispersion changing when the heaters are differentially fine-tuned. The arrows indicate the change of the dispersion curves when ring A is heated.

The dispersion curve of the 3CR system allows generation of double dispersive waves. These waves form at frequencies at which soliton frequency components are nearly resonant with cavity modes (black arrows in Fig. 2b). Controlled electrical (heater) tuning of the dispersive wave wavelength is used for matching to one of the continuous-wave lasers in the optical frequency division measurement. This capability greatly strengthens the beatnote SNR and enables flexible access to a wider range of continuous-wave lasers, whose wavelengths may not be widely tunable. Microcomb optical spectra showing different dispersive wave tunings are plotted in Fig. 2c. Tuning of the shorter wavelength dispersive wave by 4 nm and the longer wavelength dispersive wave by 8 nm is possible (Extended Data Fig. 3). It is also noted that adjusting the pump laser-microresonator detuning allows tuning of the dispersive wave35, but this provides only limited tuning range (∼0.2 nm). As an aside, the bright soliton microcomb is triggered using the method described in ref. 36, which is also illustrated in Fig. 3a.

a, Experimental set-up for bright bright soliton microcomb generation. A continuous-wave laser (Orbits lightwave) near 1,565 nm is isolated (ISO), frequency-shifted by a quadrature phase shift key modulator (QPSK) and amplified by an EDFA. The light is then bandpass filtered to reduce the amplified spontaneous emission noise and coupled to the resonator chip using a lensed fibre. The coupled on-chip power is ~150 mW. Most of the soliton power is routed to the 2P-OFD system (see text). A small portion is monitored by an optical spectrum analyser. DC, direct current. b, Phase noise spectra summary of the generated microwave signal in the 2P-OFD experiment. All noise levels are scaled to a 10 GHz carrier.

Noise limits of the generated 20 GHz microwave tone are summarized in Fig. 3b. The estimated phase noise limit from the relative phase noise of the two continuous-wave lasers is plotted in red. This is calculated by measuring the relative phase noise of the two lasers when they are Pound–Drever–Hall (PDH) locked to the same mode family of the Fabry–Pérot cavity, and when separated by one FSR (4 GHz) of the Fabry–Pérot cavity (Extended Data Fig. 2). It is assumed that the relative phase noise between the two continuous-wave lasers remains unchanged when they are separated by 3 THz in the 2P-OFD measurement (compared with the 4 GHz case). The phase noise is then scaled down by the 2P-OFD factor (49 dB to a 10 GHz carrier) to infer the noise limits in generating the 20 GHz microwave. In the current experiment, only one of the two dispersive waves is used. In principle, use of both dispersive waves would increase the 2P-OFD factor by 6 dB to 55 dB. The locking residual of the microcomb servo is plotted in purple. The SNR of the generated beatnotes f1 and f2 in Fig. 1d is limited by the noise from the photodetector PD1 and PD2; and imposes a limit of phase noise on the generated microwave. This noise is calculated in the Methods and plotted as the dashed black/grey lines for the case with (w/) and without (w/o) the dispersive wave. Other possible limits in the phase noise include amplitude-to-phase conversion inside the photodetector37,38, quantum noise of the microcomb39, amplified spontaneous emission noise from the EDFA, as well as photodetector shot noise40.

Hybrid packaging and Allan deviation

The high Q-factor property of the 3CR resonator allows low pumping power operation, enabling direct pumping by a III–V distributed-feedback laser (DFB) laser under the turnkey self-injection locking mode41. Here, a hybrid packaged module containing a III–V DFB pump and the 3CR is demonstrated (Fig. 4a and Fig. 4b show the module photograph and design concept, respectively). A commercial III–V DFB laser (Emcore Corporation) emits ∼100 mW laser light, and is collimated by a microlens. The beam passes through an anti-reflection-coated silicon slab for feedback phase tuning in the self- injection lock process, below which a resistive heater is placed for thermal tuning. After that, the beam is focused by another microlens onto the 3CR bus waveguide facet, where ∼30 mW of optical power is estimated on the chip. Dispersion of the 3CR resonator is tuned on the basis of the procedure described in the Methods, and the soliton microcomb with tunable dispersive wave is generated by approximately tuning the laser current and heating on the silicon phase section. The output of the 3CR bus waveguide is resized by two microlenses (Fig. 4b), and collected by a ferrule for fibre-coupled output. The nominal collected power in the fibre (when the DFB laser is not on resonance of the 3CR resonator) is ∼8 mW. The collected optical spectra demonstrate the tunable dispersive wave (similar to those shown in Fig. 2c; see also Supplementary Fig. 2).

a, Photograph of the hybridly packaged 3CR chip with III–V pump. b, Illustration of the packaging scheme. Output of the DFB laser is collected by a mirolens, and passes through an anti-reflection coated silicon slab for feedback phase tuning (via electrical heating). The light is lately focused by another microlens to be coupled into the Si3N4 waveguide. Heaters are deposited on the 3CR chip and wire-bonded, and dispersion is tuned to support bright soliton mode locking. The output beam of the Si3N4 waveguide is shaped by another pair of microlenses and collected by an optical fibre ferrule. c, Allan deviation results. Fractional Allan deviation of 3.6 × 10−13 is measured at an averaging time of 250 ms. For averaging times >1 s, a linear drift of 0.013 Hz s–1 is removed (detailed in Supplementary Note 3).

The hybrid packaging improves the long-term stability of the microcomb for Allan deviation characterization of the 2P-OFD system. In the packaging, the DFB and the 3CR are temperature-controlled by a thermoelectric cooler and the thermistor, respectively, with submillikelvin temperature fluctuation. The module assembly in Fig. 4a is covered by an aluminium enclosure for passive stabilization. The module is embedded in the 2P-OFD set-up (as in Fig. 1e), by feeding back to the current of the DFB laser9,42. Fractional Allan deviation of 3.6 × 10−13 is measured at the averaging time of 250 ms (Fig. 4c). It is noted that the Allan deviation benefits from the common mode suppression by locking the two continuous-wave lasers to the same mode family of the Fabry–Pérot cavity43. Refer to Supplementary Note 3 for further details on the Allan deviation measurement and analysis of the performance limit.

Discussion

In summary, record-low microwave phase noise levels have been demonstrated using a microcomb-based system. Key to this demonstration is the ability to electrically tune the spectral location of a dispersive wave, which simultaneously increases the optical frequency division ratio and locking system signal-to noise ratio. The coupled ring chip that generates the microcomb is fabricated at a CMOS foundry with high yield44, and is thus suitable for mass production. Moreover, the microcomb is demonstrated under the self-injection lock mode and hybridly integrated with a III–V pump laser, implying that entire system could be potentially miniaturized for fieldable testing. The Fabry–Pérot cavity does not require operation in vacuum while being high-performance, reducing supporting hardware and operational complexity. And the two continuous-wave lasers stabilized to the cavity can be readily miniaturized. The lasers are also stabilized without extra bulky fibre-optic components (for example, acoustic optic modulators)9,27. These combined features mean that the architecture simplifies the optical frequency division system and is potentially manufacturable and fieldable. Finally, we would like to note two related papers that were published during the preparation of this manuscript45,46.

Methods

Dispersion modelling of the 3CR resonator

In this section we outline the theory that describes the dispersion spectrum of the 3CR resonator (calculation of the dispersion is detailed in ref. 24). Briefly, a transfer matrix, T, is used to propagate a three-component wave function through a round trip.

The resulting secular equation gives the eigenfrequencies, ω, of the three mode families (see plot in Fig. 2a), where m is mode number, ϵ1 ≡ (LB − LC)/2 L and ϵ2 ≡ (LB + LC − 2LA)/6 L. Here, L ≡ (nwg,BlB + nwg,ClC)/2 is the averaged optical path length of rings B and C (left and right rings), Li ≡ nwg,ili is the round trip optical path length of any of the three rings (i = A,B,C), where nwg,i is the effective index of the waveguide that forms the ring (which can be tuned via the thermo-optic effect) and li is the physical round trip length of an individual ring (which can be tuned via the thermo-elastic effect); gco is the amplitude coupling strength per unit length between the neighbouring rings (rings A and B; rings A and C); lco is the physical length of the coupling section.

The secular equation after a round trip can be simplified to a polynomial equation,

where x ≡ eiθ and \(\omega ={\omega }_{m}-\frac{D_1}{2{\uppi}}\theta\), with ωm = 2πmc/L; D1/2π the average FSR of the three rings and c the speed of light in vacuum; ϕ1 ≡ 2πmϵ1 and ϕ2 ≡ 2πmϵ2 are parameters that govern the dispersion spectrum. Three dispersion bands will be formed since equation (2) is a third-order polynomial of x.

Equation (2) does not have a simple solution, but there are still features that can be inferred in terms of the dispersion spectrum. For example, ϕ1 = 2πϵ1mo = 2πN (N is an integer) defines the mode number where the dispersion curves of the uncoupled rings B and C will intersect (Fig. 2a). At this mode number the corresponding wavelength is λo. For the device used in this study, ϵ1 ≈ 3 × 10−3 by design and is measured to be within 1% of this value. ϵ2 is measured to be ϵ2 ≈ 10−5, which is consistent with a design target close to zero. However, slight fabrication variances modify the dispersion curve and impair soliton mode locking at the pump wavelength. To acquire dispersion bands that are favourable for soliton mode locking, heater tuning is applied to tune λ0 (mo) and ϕ2. After the heater tuning, the dispersion is as shown in Fig. 2a wherein the fitted parameters are ϕ2 = −0.36, and gcolco = 0.9 near λo = 1,568 nm (mo ≈ 9,567). Further details on this tuning procedure are given below.

Differential heater tuning of the three-coupled-ring resonator

Based on the analysis in the previous section, the dispersion curve is determined by two parameters ϕ1 and ϕ2. Experimentally, ring B (or C) is thermally tuned to change ϕ1 and, in turn, λo. Ring A is thermally tuned to change ϕ2 and, in turn, can be shown to tune the GVD parameter at λo. Specifically, differential heating of ring A increases the curvature of the pumped band near λo (amount of anomalous dispersion), as in the inset of Fig. 2c. These tuning steps are largely independent and enable a two-step dispersion tuning protocol described in Extended Data Fig. 3a. In the first step, ring B is tuned (ϕ1 is tuned) such that λo is tuned close to the pump wavelength (1,565 nm). In the second step, ring A is tuned (ϕ2 is tuned) with ϕ1 unchanged. The resulting dispersion is shown in the lower panel of Extended Data Fig. 3a (also in Fig. 2b).

The dispersion tuning is efficient, requiring only a moderate amount of actual temperature tuning. Tuning of λo benefits from the Vernier effect, as described in ref. 15, and, experimentally, ∼10 °C of differential temperature tuning is sufficient to tune the pump wavelength λo across the optical C band. The local curvature of the dispersion bands (GVD parameter) near λo is determined by differential thermal tuning in ring A. The tuning of uncoupled mode resonance in ring A by one FSR (20 GHz) will access all the possible dispersion configurations. This corresponds to tuning of LA by L/m. With a large mode number m ≈ 104 in the optical C band, this corresponds to <10 °C of differential temperature tuning.

High-finesse, vacuum-free and miniaturized Fabry–Pérot cavity

The cavity is made of high purity fused silica with high-reflectivity coatings on both sides to form resonance. It is cylindrical in shape, 25.4 mm in length and 15 mm in diameter; see the photograph of Fig. 1c. The dielectric coatings (SiO2/Ta2O5) at 1,550 nm are deposited on both surfaces (plano-convex with 1 m radius of curvature). Since the cavity is solid silica, a vacuum chamber and associated equipment are not required. By using a continuous-wave laser to sweep across the cavity resonance, the reflection of the cavity reveals the cavity linewidth to be 24 kHz (quality factor = 8.2 billion); see the measurement and fitting in the inset of Fig. 1c. The vibration sensitivity of the cavity is designed and measured to be 10−10 g–1 by using the vibration-insensitive scheme demonstrated in ref. 14. The Fabry–Pérot cavity is installed in a multi-layer thermal shield, providing insulation (~20 mins time constant) to damp the impact of ambient temperature fluctuation.

By PDH locking individual lasers (Toptica DLC pro and the RIO PLANEX) to neighbouring fundamental modes of the cavity47 and then detecting the beatnote of the two lasers with a fast photodetector (Thorlabs DXM30AF), a 4 GHz microwave tone (one cavity FSR) is generated. This tone both with and without PDH lock is measured using an R&S FSWP signal analyser (Extended Data Fig. 2). The phase noise spectra show a large noise reduction from the cavity locking. The red curve in Extended Data Fig. 2 is reproduced in Fig. 3b for comparison to the 2P-OFD microwave phase noise spectrum. Considering the noise reduction due to 2P-OFD, which is 49 dB (when scaled to a 10 GHz carrier), the projected microwave phase noise is approximately >10 dB lower than the measured phase noise of the comb repetition rate (blue).

Details of the 3CR resonator

For the device used in the study, the intrinsic Q-factor of the pumped mode is around 100 million, and the experimental threshold power for parametric oscillation is around 3 mW. Furthermore, the FSR is 19.869 GHz and the local GVD parameter is D2/2π ≈ 50 kHz. Refer to ref. 42 for details on other parameters.

Impact of beatnote SNR on the 2P-OFD

The enhancement of SNR resulting from the agile dispersive wave is critical to increasing the OFD factor for low-noise microwave generation. In the 2P-OFD, the limited SNR of the f1 + f2 beatnote (as in Fig. 1e) will impose a flat (that is, constant) phase noise on the generated microwave tone. Specifically, the phase noise (in the unit of decibels relative to the carrier per hertz) is denoted by

where SNR is signal-to-noise ratio of the beatnote (f1 + f2) used for locking, under a certain resolution bandwidth (100 kHz in this work). The SNR of the mixed f1 + f2 beatnote is limited by the beatnote with lower SNR (the f2 beatnote in this work). Based on equation (3) and the measurement in Fig. 1b, with the dispersive wave, the SNR-limited phase noise is calculated as −159 dBc Hz–1 (when scaled to a 10 GHz carrier). Without the dispersive wave enhanced SNR, the SNR-limited phase noise is calculated as −129 dBc Hz–1 (when scaled to a 10 GHz carrier). In practice, without the dispersive wave enhancement, the SNR is too low for a reliable locking; thus the phase noise data are not acquired.

Data availability

The data that support the plots within this paper and other findings of this study are available on figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27676482 (ref. 48). All of the other data used in this study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

Code availability

The codes that support findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

References

Diddams, S. A., Vahala, K. & Udem, T. Optical frequency combs: coherently uniting the electromagnetic spectrum. Science 369, eaay3676 (2020).

Fortier, T. M. et al. Generation of ultrastable microwaves via optical frequency division. Nat. Photon. 5, 425–429 (2011).

Xie, X. et al. Photonic microwave signals with zeptosecond-level absolute timing noise. Nat. Photon. 11, 44–47 (2017).

Nakamura, T. et al. Coherent optical clock down-conversion for microwave frequencies with 10–18 instability. Science 368, 889–892 (2020).

Swann, W. C., Baumann, E., Giorgetta, F. R. & Newbury, N. R. Microwave generation with low residual phase noise from a femtosecond fiber laser with an intracavity electrooptic modulator. Opt. Express 19, 24387–24395 (2011).

Li, J., Yi, X., Lee, H., Diddams, S. A. & Vahala, K. J. Electro-optical frequency division and stable microwave synthesis. Science 345, 309–313 (2014).

Li, J. & Vahala, K. Small-sized, ultra-low phase noise photonic microwave oscillators at X-Ka bands. Optica 10, 33–34 (2023).

He, Y. et al. Chip-scale high-performance photonic microwave oscillator. Sci. Adv. 10, eado9570 (2024).

Kudelin, I. et al. Photonic chip-based low-noise microwave oscillator. Nature 627, 534–539 (2024).

Sun, S. et al. Integrated optical frequency division for microwave and mmWave generation. Nature 627, 540–545 (2024).

Zhao, Y. et al. All-optical frequency division on-chip using a single laser. Nature 627, 546–552 (2024).

Kwon, D., Jeong, D., Jeon, I., Lee, H. & Kim, J. Ultrastable microwave and soliton-pulse generation from fibre-photonic-stabilized microcombs. Nat. Commun. 13, 381 (2022).

Ji, Q.-X. et al. Coherent optical-to- microwave link using an integrated microcomb. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSTQE.2024.3451301 (2024).

Zhang, W. et al. Ultranarrow linewidth photonic-atomic laser. Laser Photon. Rev. 14, 1900293 (2020).

Ji, Q.-X. et al. Multimodality integrated microresonators using the moire speedup effect. Science 383, 1080–1083 (2024).

Xue, X. et al. Normal-dispersion microcombs enabled by controllable mode interactions. Laser Photon. Rev. 9, L23–L28 (2015).

Kippenberg, T. J., Gaeta, A. L., Lipson, M. & Gorodetsky, M. L. Dissipative Kerr solitons in optical microresonators. Science 361, eaan8083 (2018).

Brasch, V., Lucas, E., Jost, J. D., Geiselmann, M. & Kippenberg, T. J. Self-referenced photonic chip soliton Kerr frequency comb. Light Sci. Appl. 6, e16202 (2017).

Brasch, V. et al. Photonic chip–based optical frequency comb using soliton Cherenkov radiation. Science 351, 357–360 (2016).

Spencer, D. T. et al. An optical-frequency synthesizer using integrated photonics. Nature 557, 81–85 (2018).

Newman, Z. L. et al. Architecture for the photonic integration of an optical atomic clock. Optica 6, 680–685 (2019).

Yi, X. et al. Single-mode dispersive waves and soliton microcomb dynamics. Nat. Commun. 8, 1–9 (2017).

Okawachi, Y. et al. Active tuning of dispersive waves in Kerr soliton combs. Opt. Lett. 47, 2234–2237 (2022).

Yuan, Z. et al. Soliton pulse pairs at multiple colours in normal dispersion microresonators. Nat. Photon. 17, 977–983 (2023).

Zhang, W. et al. Monolithic optical resonator for ultrastable laser and photonic millimeter-wave synthesis. Commun. Phys. 7, 177 (2024).

Jin, N. et al. Micro-fabricated mirrors with finesse exceeding one million. Optica 9, 965–970 (2022).

Guo, J. et al. Chip-based laser with 1-Hertz integrated linewidth. Sci. Adv. 8, eabp9006 (2022).

McLemore, C. A. et al. Miniaturizing ultrastable electromagnetic oscillators: sub-10–14 frequency instability from a centimeter-scale Fabry–Perot cavity. Phys. Rev. Appl. 18, 054054 (2022).

Ilchenko, V. S. & Matsko, A. B. Optical resonators with whispering-gallery modes-part II: applications. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 12, 15–32 (2006).

Liu, K. et al. 36 Hz Integral linewidth laser based on a photonic integrated 4.0 m coil resonator. Optica 9, 770–775 (2022).

Liu, Y. et al. High Finesse, Air-Gap Optical Reference Cavity for Low Noise Microwave Generation CLEO: Science and Innovations, SM2K–4 (Optica Publishing Group, 2023).

Yang, Q.-F. et al. Dispersive-wave induced noise limits in miniature soliton microwave sources. Nat. Commun. 12, 1442 (2021).

Lucas, E. et al. Ultralow-noise photonic microwave synthesis using a soliton microcomb-based transfer oscillator. Nat. Commun. 11, 1–8 (2020).

Dorche, A. E., Abdollahramezani, S., Taheri, H., Eftekhar, A. A. & Adibi, A. Extending chip-based Kerr-comb to visible spectrum by dispersive wave engineering. Opt. Express 25, 22362–22374 (2017).

Yang, Q.-F., Yi, X., Yang, K. Y. & Vahala, K. Spatial-mode-interaction-induced dispersive-waves and their active tuning in microresonators. Optica 3, 1132–1135 (2016).

Stone, J. R. et al. Thermal and nonlinear dissipative-soliton dynamics in Kerr-microresonator frequency combs. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 063902 (2018).

Zhang, W. et al. Amplitude to phase conversion of InGaAs pin photo-diodes for femtosecond lasers microwave signal generation. Appl. Phys. B 106, 301–308 (2012).

Zang, J. et al. Reduction of amplitude-to-phase conversion in charge-compensated modified unitraveling carrier photodiodes. J. Lightwave Technol. 36, 5218–5223 (2018).

Matsko, A. B. & Maleki, L. On timing jitter of mode locked Kerr frequency combs. Opt. Express 21, 28862–28876 (2013).

Quinlan, F. et al. Exploiting shot noise correlations in the photodetection of ultrashort optical pulse trains. Nat. Photon. 7, 290–293 (2013).

Shen, B. et al. Integrated turnkey soliton microcombs. Nature 582, 365–369 (2020).

Ji, Q.-X. et al. Engineered zero-dispersion microcombs using CMOS-ready photonics. Optica 10, 279–285 (2023).

Groman, W. et al. Photonic millimeter-wave generation beyond the cavity thermal limit. Optica 11, 1583–1587 (2024).

Jin, W. et al. Hertz-linewidth semiconductor lasers using CMOS-ready ultra-high-Q microresonators. Nat. Photon. 15, 346–353 (2021).

Jin, X. et al. Microresonator-referenced soliton microcombs with zeptosecond-level timing noise. Nat. Photon. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-025-01669-2 (2025).

Sun, S. et al. Microcavity Kerr optical frequency division with integrated SiN photonics. Nat. Photon. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-025-01668-3 (2025).

Drever, R. et al. Laser phase and frequency stabilization using an optical resonator. Appl. Phys. B 31, 97–105 (1983).

Ji, Q.-X. et al. Dispersive-wave-agile optical frequency division. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27676482 (2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank I. Kudelin, F. Quinlan and S. Diddams at NIST, X. Yi at University of Virginia for fruitful discussions, as well as M. Gao, J. Ge, Y. Yan and Z. Yuan at Caltech for experimental assistance. This work is supported by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency GRYPHON programme (grant no. HR0011-22-2-0009), NASA USTP (University Smallsat Technology Partnership, award ID no. 80NSSC23M0239), the Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity (IARPA) via the Department of Interior/Interior Business Center (DOI/IBC) contract no. 140D0423C0112, and the Kavli Nanoscience Institute at Caltech. The research reported here was performed by W.Z., A.S., V.I. and A.M. at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory at the California Institute of Technology, under a contract with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (grant no. 80NM0018D0004). The US Government is authorized to reproduce and distribute reprints for Governmental purposes notwithstanding any copyright annotation thereon. Disclaimer: The views and conclusions contained herein are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as necessarily representing the official policies or endorsements, either expressed or implied, of DARPA, IARPA, DOI/IBC or the US Government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Concepts were developed by Q.-X.J., W.Z., P.L., W.J., J.B., A.M. and K.V. The 3CR resonator was designed and fabricated by W.J. with input from J.G., J.P. L.W., Q.-X.J., A.F., M.P. and J.B. The Fabry–Pérot cavity subsystem was designed and built by W.Z. with assistance from Q.-X.J. Measurements and modelling were performed by Q.-X.J., W.Z., P.L. and S.S. The microcomb was packaged by A.S. and V.I., with input from Q.-X.J. All authors contributed to the writing of the paper. The project was supervised by W.Z., A.M., J.B. and K.V.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Kerry Vahala is a co-founder and stock holder of hQphotonics. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Photonics thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Measured beatnotes f1 and f2 in Fig. 1 with and without dispersive-wave enhancement.

a, Measured beatnote between the stabilized c.w. laser (\({\nu }_{1}\)) and comb line (\({\nu }_{m}\)), where \({f}_{1}\) is 507.4 MHz. An SNR of 65 dB is measured with resolution bandwidth of 100 kHz. b, Measured beanote between the stabilized c.w. laser (\({\nu }_{2}\)) and the dispersive wave (\({\nu }_{n}\)). An SNR of 60 dB is measured with resolution bandwidth of 100 kHz. \({f}_{2}\) is 743.6 MHz for the case with dispersive wave, and \({f}_{2}\) = 979.9 MHz for the case without the dispersive wave. A 30 dB improvement in SNR is demonstrated with the dispersive wave. Without this SNR improvement, it is improbable to lock the 2P-OFD.

Extended Data Fig. 2

Relative phase noise of the two c.w. lasers, when both are free-running (black) and PDH stabilized to the Fabry–Perot cavity (red).

Extended Data Fig. 3 Dispersion tuning and dispersive wave tuning in the bright soliton microcomb using electrical heaters.

a, Upper panel: measured dispersion spectrum of the 3-coupled-ring (3CR) resonator with random heater tuning. Middle panel: measured dispersion spectrum of the 3CR after tuning \({\lambda }_{{\rm{o}}}\) closer to the pump wavelength (1565 nm) by heating ring B. Lower panel: measured dispersion spectrum of the 3CR after the local GVD parameter is tuned by heating ring A. b,c, Measurement of dispersive wave tuning when ring A (B) is fine-tuned. The 1542 nm dispersive wave is plotted in blue, while the 1590 nm dispersive wave is plotted in red. The corresponding data points in Fig. 2c and panel d are indicated by the arrows (matched by the colours). d, Measured optical spectra of the bright soliton microcomb with three different dispersive wave tunings. Inset: theoretical dispersion spectra when ring B is tuned. The arrow indicates the change of the dispersion curves when ring B is heated.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–4 and Discussion.

Supplementary Data

Data for Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ji, QX., Zhang, W., Savchenkov, A. et al. Dispersive-wave-agile optical frequency division. Nat. Photon. 19, 624–629 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-025-01667-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-025-01667-4

This article is cited by

-

Microresonator-referenced soliton microcombs with zeptosecond-level timing noise

Nature Photonics (2025)

-

Microcavity Kerr optical frequency division with integrated SiN photonics

Nature Photonics (2025)

-

Observation of the universality of nonlinear mode coupling in a fibre laser

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Deterministic soliton microcombs in Cu-free photonic integrated circuits

Nature (2025)