Abstract

In the past few decades, the development of ultrafast lasers has revolutionized our ability to gain insight into light–matter interactions. The emergence of few-cycle light sources operating from the visible to the mid-infrared spectral range—as well as attosecond extreme ultraviolet and X-ray technologies—provide the possibility to directly observe and control ultrafast electron dynamics in matter on their natural timescale; however, the temporal characterization of few-femtosecond sources in the deep ultraviolet (4–6 eV, 300–200 nm) and the vacuum ultraviolet (VUV; 6–12 eV, 200–100 nm) spectral regions is challenging. Here we fully characterize the temporal shape of microjoule-energy VUV pulses tuned between 160 and 190 nm generated via resonant dispersive wave emission during soliton self-compression in a capillary using frequency-resolved optical gating based on two-photon photoionization in noble gases. The in situ measurements reveal that in most of the cases the pulses are shorter than 3 fs. These findings pave the way toward investigating ultrafast electron dynamics and valence excitation of a large class of atoms and molecules with a time-resolution that has been hitherto inaccessible when using VUV pulses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The investigation of ultrafast electron dynamics has become more accessible in the past two decades with the development of attosecond extreme ultraviolet (XUV) light sources1. However, due to its high photon energy (above 20 eV), a single XUV photon can directly ionize matter, which limits the scope of investigations to ionization-driven or core-excited electron dynamics2. Ultraviolet, visible or infrared pulses of the shortest possible duration are needed to answer a manifold of fundamental questions in physics and chemistry3. Understanding, for example, the photoexcitation dynamics of molecules on visible and ultraviolet absorption presents a considerable challenge, particularly due to the breakdown of the Born–Oppenheimer approximation according to which fast-moving electrons can instantaneously adjust to the slower motion of nuclei. In electronically excited molecules, the presence of closely spaced electronic states can result in strongly coupled electronic and nuclear dynamics along one or more reactive modes, making it impossible to treat them separately. These couplings lead to radiationless non-adiabatic transitions occurring on ultrafast timescales.

The generation of few-femtosecond ultraviolet pulses that would allow for temporally resolving ultrafast valence electron dynamics is a very challenging task. In particular, the proximity of electronic resonances—which are present in virtually all materials in the ultraviolet spectral range—results in both increased linear absorption and high dispersion. The latter is detrimental to the temporal resolution smearing out the initially short pulses to long duration in the course of propagation. In practice, no material can be tolerated as a propagation medium, making the handling of ultrashort ultraviolet pulses extremely difficult. Indeed, only a few groups achieved microjoule-level sub-10-fs pulses in the deep ultraviolet (DUV) through standard nonlinear optical methods, including four-wave mixing in a hollow-core fibre (HCF)4,5 or achromatic second-harmonic generation6,7, or even shorter, few-cycle pulses, through low-order harmonic generation in noble gases8,9,10,11,12. The last approach proved especially useful, not only because it generated sufficiently short pulses for the investigation of ultrafast dynamics in matter on few-femtosecond timescales, but also because it is based on a well-engineered technology, which is routinely used nowadays for the generation of attosecond pulses in the XUV. One drawback remains though, namely, the lack of spectral tunability. In principle, this could be overcome by driving the harmonic generation process with a few-cycle parametric source broadly tunable in the infrared; however, this requires a multi-octave phase-matching bandwidth of the parametric process, which remains to be demonstrated.

An alternative solution towards the generation of few-cycle pulses tunable across the entire ultraviolet range is offered by fibre technology. The appearance of hollow-core photonic-crystal fibres (HC-PCF)13,14 with engineered dispersion properties, and gas as a nonlinear medium, paved the way to exploiting physical phenomena such as the formation of optical solitons15,16 for a new class of ultrafast light source. Optical solitons can emerge in a medium in which the sign of the optical Kerr-effect is opposite to that of the dispersion. In this scenario the two effects can balance each other leading to a dispersionless propagation, where the pulse shape remains unchanged, or the pulses can even become compressed accompanied by a giant spectral broadening often yielding an over-octave-spanning supercontinuum. In this specific case, if the newly generated spectra reach a region in which their phase velocity matches that of the soliton, a very effective energy transfer from the soliton to this spectral region can occur. This phase matching leading to the creation of resonant dispersive wave radiation mostly happens at shorter wavelengths, for example, in the ultraviolet. The overall dispersion of the gas-filled waveguide and thus the resonant wavelength can easily be tuned across the ultraviolet by varying the gas pressure in the core17. Indeed, soliton self-compression and accompanying resonant dispersive-wave (RDW) generation in the ultraviolet were theoretically predicted18 for HC-PCFs with a negative dispersion profile, and were experimentally demonstrated shortly after19,20. Owing to the rather small dimensions of the PCF structures, these sources are capable of delivering few-femtosecond pulses with pulse energies of up to ~1 µJ (ref. 21), which is often insufficient for investigating ultrafast dynamics in dilute targets such as gas-phase molecules, taking into account the loss-prone spectral separation from the broadband soliton content and beam delivery. This limitation is largely mitigated by capillaries with moderate core diameters, which can also exhibit negative dispersion, allowing the same soliton dynamics as in PCFs but in a strongly up-scaled manner, yielding pulse energies in the multi-microjoule range22. Indeed, high-energy self-compression in HCFs was demonstrated by Travers et al.22 a few years ago, currently leading to widespread implementation of this technique in many laboratories around the world.

Although the ultraviolet pulse generation mechanism in HCFs itself is robust and well understood, there are a few hurdles to be overcome23 to harvest the full potential of such sources in contemporary ultrafast science. In certain conditions the ultraviolet pulses emerging from the waveguide are expected to be close to their Fourier-transform-limited temporal shape. The passage through even a thin window, usually used for enclosing the gas within the waveguide, irreparably deteriorates the pulse shape, as chirp-management capabilities are scarce in the DUV and practically non-existent in the vacuum ultraviolet (VUV). Therefore, the output of the capillary needs to be directly injected into the vacuum apparatus in which the experiments using the DUV or VUV pulses are performed. The gas used as nonlinear medium is filled at the entrance side, whereas the pressure gradually drops to zero towards the output24. Furthermore, the RDW pulse emerges superimposed on the fundamental soliton, and needs to be spectrally separated from it.

The last—and inevitably most difficult—challenge is the full temporal characterization of the broadband few-cycle ultraviolet pulses having a predicted typical duration of between 2 fs and 5 fs. Although the first temporal characterization of RDW pulses in the DUV has been recently performed, no characterization has yet been reported in the much more difficult VUV range. Sub-3-fs RDW pulses tunable from 250 nm to 350 nm were measured with a self-diffraction frequency-resolved optical gating (FROG) arrangement, placed in the vacuum beamline25, using a 50-µm-thick CaF2 plate as the nonlinear medium. Although these results exploit the full potential of all-optical pulse measurement methods, such techniques are not applicable for pulses centred at even shorter wavelengths due to excessive dispersion. The influence of high absorption and material dispersion of the nonlinear medium on the pulse characterization can be mitigated by using noble gases at low pressure possessing orders of magnitude lower density than solids, thereby leading to low dispersion. In such low-density media the nonlinearities frequently used in pulse characterization schemes, such as low-order harmonic generation or those using the optical Kerr-effect (self-diffraction or transient grating formation) yield non-measurable signals. An alternative is to use photoionization and detect ions as a function of the delay between two pulse replicas yielding an autocorrelation signal10. However, although autocorrelation measurements provide an estimation of the pulse duration assuming a specific shape, they cannot fully characterize the pulse, which requires both amplitude and phase information.

Here we present the temporal characterization of few-cycle VUV pulses tuned between 160 nm and 190 nm by photoionization of an atomic gas using a sequence of two pulse replicas. We use a variant of the FROG technique26 based on photoelectron spectroscopy27,28 (electron-FROG, hereafter eFROG). Our measurements are validated by comparing the results of our experiments with ab initio calculations of the two-photon ionization dynamics of atoms and also with simulations of the VUV pulse generation process.

Results

In our experiments we generate few-femtosecond pulses with tens of microjoules of energy tunable across the VUV via RDW emission in a cascaded capillary arrangement seeded by a 800 nm Ti:sapphire laser (see Methods for details; a sketch of the full arrangement is displayed in Fig. 1). First, we compress the laser pulses to ~10 fs duration by passage through a gas-filled stretched flexible hollow-core fibre29 (SF-HCF). The compressed pulses are then coupled into a second gas-filled SF-HCF where soliton self-compression and RDW emission take place. We inject helium at the entrance of the second capillary while the output side is directly connected to a vacuum beamline yielding a gradually decreasing gas pressure along the waveguide. The beam emerging from the second SF-HCF is first re-collimated, and then the broadband soliton content is filtered out by Brewster-reflections off of two consecutive silicon plates. The filtered RDW pulses are then measured either by a VUV spectrometer and a power meter, or sent into the eFROG apparatus for full temporal characterization. In the eFROG apparatus a pair of D-shaped mirrors splits the pulse front in half and introduces a delay between the two halves. The two half-beams are focused into a velocity-map imaging (VMI) spectrometer30, in which they are used to ionize atoms of a noble gas. While scanning the delay between the two pulse replicas, we record the velocity distribution of the photoelectrons resulting from two-photon ionization of the atomic gas using a detector consisting of a sequence of two multi-channel plates (MPC), a phosphor screen and a digital camera (see Supplementary Section 1 for a detailed description of the data acquisition and processing).

The pulses of the Ti:sapphire laser are first compressed to ~10 fs duration using an argon-filled capillary (HCF1) and a set of chirped mirrors (CM). Soliton compression and RDW generation take place in a second, helium-filled capillary (HCF2). A half-wave plate (HWP) and a wire-grid polarizer (WGP) can set the pulse energy. The RDW pulses are first filtered by Brewster reflections off of two silicon plates. The power and the spectrum of the VUV radiation can be measured by a power meter (PM) and a spectrometer (SP). In the eFROG setup two pulse replicas are created by a split-and-delay mirror pair and then focused into a gas jet placed inside of a VMI spectrometer that measures the kinetic energy spectrum of the produced photoelectrons at varying delays between the pulse replicas. a,b, The insets (a,b) display two exemplary measured eFROG traces, where xenon atoms are photoionized by VUV pulses centred at 180 nm and 170 nm, respectively. In a the imprint of AIS is observed at low energy (<1 eV), whereas in b a double-peak structure is observed due to spin–orbit splitting in the xenon atoms.

Our method to characterize the temporal profile of the VUV pulse relies on recording the delay-dependent kinetic energy distribution of photoelectrons resulting from non-resonant two-photon ionization of an atomic gas target. If the ionization process occurs on a timescale much shorter than the pulse duration, that is, away from any resonances, then this method is analogous to an all-optical second-harmonic generation FROG, where the nonlinearity can be simply calculated in the time domain by a multiplication of the electric field by its time-shifted replica. The ionization process poses clear conditions for the choice of the gas species, depending on the generated VUV spectrum: (1) two photons should be able to ionize the atoms, meaning that the photon energy of the red side of the spectrum should exceed half of the ionization potential; and (2) electronic excitation of the atoms should be excluded because it would lead to a non-instantaneous sequential ionization. Condition (2) implies that the photon energy at the short-wavelength wing of the spectrum should remain below the lowest-lying Rydberg transition. According to these criteria, the entire VUV spectral range can be covered by noble gases (Extended Data Table 1).

Figure 1a,b represents two eFROG traces measured using pulses centred at 180 nm and 170 nm for the photoionization of xenon atoms. Both traces possess features that are unknown from second-harmonic generation FROG traces: sharp horizontal lines in Fig. 1a and a double-peaked structure in Fig. 1b, although the pulse spectrum itself exhibits a single peak. To understand the origin of these features we need to have a closer look at the atomic structure of the nonlinear medium. Rare gas atoms have two ionization thresholds close in energy that are separated by spin–orbit splitting (see Fig. 2a). Due to the two different ionization channels and depending on whether the ion is formed in the 5p5 2P3/2 or the 5p5 2P1/2 state, the kinetic energy spectrum of the photoelectrons consists of two slightly shifted replicas (see Fig. 2c). In a scenario in which the ionization channel leads to the formation of the ion in the 5p5 2P1/2 state, which requires higher photon energies, the broad VUV spectrum might violate (1), leading to the excitation of auto-ionizing states (AIS) that modulate the low-energy region of the kinetic energy spectrum (see Fig. 2b).

a, Energy level diagram of xenon, where IP denotes the ionization potential, showing the two possible ionization channels and the lower and upper bounds for the spectrum of the VUV pulse that can be characterized by xenon. A schematic of the resulting kinetic energy spectrum is shown to the right. Ionization producing the 5p5 2P3/2 state can occur either through direct non-resonant two-photon ionization or through two-photon excitation of an AIS converging on the 5p5 2P1/2 state. Ionization producing the 5p5 2P1/2 state is only possible through direct non-resonant two-photon excitation above the 5p5 2P1/2 threshold. b,c Measured kinetic energy spectra corresponding to the measured eFROG traces in Fig. 1a,b, respectively.

In the case of long pulses with a narrow spectrum (bandwidth < spin–orbit splitting), the two contributions to the photoelectron kinetic energy spectrum do not overlap and a simple spectral filtering can discriminate the two spin–orbit pathways, as was done in a former measurement of 50-fs-long pulses27. However, for very short pulses with a broad spectrum spanning more than 1 eV bandwidth, as used in our study, the two pathways partially overlap. We therefore developed a simple heuristic model assuming that the two ionization channels are independent from each other, and yield two identical contributions with an energy shift corresponding to the spin–orbit splitting. The eFROG trace is then an incoherent sum of both contributions with different weights. Furthermore, the imprint of the AIS on the eFROG measurement is taken into account as a contribution to the spectral response function, which is a commonly used approach to match the calculated trace to the measurement in each iteration of the retrieval. We implement this model in the phase retrieval on the basis of a modified differential evolution algorithm (see Methods for details), which runs sufficiently fast so that the evaluations could be performed on a desktop computer.

Before we characterize the tunable VUV pulses, we investigate whether our algorithm based on a simple model can: (1) sufficiently grasp the most significant features of the underlying photoionization processes, and (2) accurately retrieve the electric field of a short pulse from eFROG traces. First, we perform phase retrievals on the two exemplary measured traces shown in Fig. 1a,b. We observe a very good match between the measured (Fig. 3a,g) and retrieved (Fig. 3b,h) traces, which suggests that our model is good at capturing the photoionization mechanisms such as the AIS, as well as the two ionization channels. The FROG errors on the 74 × 132 size grid amount to 2.5% and 2.1%, respectively. Furthermore, to address (2) we test our algorithm against ab initio quantum-mechanical calculations based on solving the time-dependent Schrödinger equation (TDSE) (Methods). To that end, the electric fields obtained by the retrievals (shown in Fig. 3b,h) are fed into the TDSE solver to calculate the kinetic energy distribution of the photoelectrons at each delay, thus simulating their corresponding eFROG traces. We then use the calculated traces as an input for further phase retrievals (shown in Fig. 3d,j). The retrieved pulse shapes (Fig. 3e,k) and the spectral phases (Fig. 3f,l) are very good at reproducing the known input shapes, which is quantified by the low values of the root-mean-square field errors (ε; see Methods) indicated in Fig. 3e,k. These results strongly indicate the suitability of our heuristic model to retrieve the pulse shape from eFROG measurements with high fidelity.

a–l, The first (a,g), second (b,h) and third (c,i) columns show the measured, retrieved and ab initio-calculated traces, respectively; the fourth column (d,j) corresponds to retrievals using the simulated traces as an input; and the fifth (e,k) and sixth (f,l) columns display the pulse shapes and spectra with spectral phases, respectively. In the last two columns, the input shapes of the simulations are denoted by dotted lines, whereas the retrieved shapes by solid lines. Traces exhibiting AIS fingerprints, RDW pulses centred at 180 nm (top row); traces exhibiting contributions of the two ionization channels, RDW pulses centred at 170 nm (bottom row).

After gaining confidence in our retrievals, we reconstruct the temporal shape of VUV pulses tuned between 160 and 190 nm from a series of eFROG measurements. The average temporal envelopes and phases retrieved from the eFROG traces using our algorithm are summarized in Fig. 4 (see Supplementary Fig. 2 for the full set of data). The pulse shapes are very similar for all pulses at different central wavelengths exhibiting a slight chirp. The chirp is attributed partly to the generation process, and partly to propagation through the dilute gas medium at a few millibars of pressure originating from the capillary. The pulse durations, defined by the full-width at half-maximum, are below 3 fs, with the exception of the pulse with a central wavelength of 190 nm (pulse D in Fig. 4). We note that in case D the slightly increased pulse duration is accompanied by a doubling of the VUV pulse energy yielding a maximal peak power of ~0.8 GW.

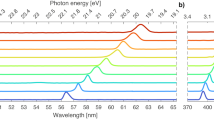

a, The spectra measured by a VUV spectrometer. b, The average temporal envelopes (solid) and phases (dotted) retrieved from ten independent retrievals of the measured eFROG traces. The shaded areas surrounding the envelopes and phases correspond to the s.d. of the retrievals. The transform limited (TL) pulse shapes corresponding to the measured spectra are displayed as shaded backgrounds. The full-width at half-maximum values of each shape are also included. The VUV pulse energies measured behind the Brewster-angled silicon plates are indicated in the upper left corner of each panel.

Discussion

We compare the measured pulse shapes with the results of simulations proven to describe the generation of RDW pulses at high fidelity. For the simulations we solve the unidirectional pulse propagation equation along the hollow waveguide taking the first four eigenmodes into account using the open-source Luna library31. Refer to Supplementary Section 3 for details on the simulations, including the full set of input parameters corresponding to our VUV generation conditions.

In Fig. 5 the results of the simulation are compared with the measured spectra and pulse shapes, showing excellent overall agreement. Interestingly, the agreement is better between the filtered fundamental mode and the measurement, which we attribute to the filtering effect of the finite aperture of the steering mirrors during the long propagation towards the eFROG apparatus.

The columns correspond to the pulses A–D of Fig. 3. The spectra are displayed in the top row while the pulse shapes are shown in the bottom row. Solid lines represent the output of the simulation, the dashed lines correspond to the fundamental eigenmode, and the dotted lines denote the experimentally measured data. In the top row the shaded areas correspond to the measured spectra, whereas in the bottom row the shaded regions mark the s.d. of the retrieved pulse shapes.

As an experimental validation of our method, we determine the phase shift due to an ultra-thin fused silica plate placed into the VUV beam. We measure eFROG traces with and without inserting a 10-µm-thin ultraviolet fused silica plate in the beam. The measured phase shift introduced by the plate is the difference between the two retrieved phases (solid curve in Fig. 6). For comparison, the phase shift due to the plate (dashed curve) is calculated using the VUV refractive index of fused silica32 in combination with the thickness of the plate (Methods).

The solid line corresponds to the difference between the average phases of ten retrievals with and without the plate. The shaded area marks the uncertainty of the measured phase difference. The calculated phase imparted by the silica plate is plotted by the dashed dark red line. The large absorption coefficient of fused silica is displayed as a black dotted line. The spectrum of the VUV pulse is shown in the background for reference.

The agreement between the measured and the calculated phase difference is remarkable. Only a slight deviation of the two curves is observable below 170 nm, where the absorption of fused silica rapidly increases distortions of the pulse.

Conclusion

Until recently, the lack of few-cycle ultraviolet pulses prevented fundamental studies in a spectral range in which most materials exhibit electronic resonances. High-energy RDW emission emerging from a hollow capillary fibre22 offers a versatile light source for such experiments. Indeed, the first pump–probe experiments involving few-femtosecond DUV pulses were performed recently33,34,35; however, no studies have been reported in the more challenging VUV spectral range until now. Furthermore, although numerical simulations suggest that VUV pulses due to RDW emission can also be very short (few-femtosecond duration), until now no experimental evidence confirmed these predictions. Here we characterized VUV pulses tunable between 160 and 190 nm with sub-3-fs duration carrying a few microjoules of energy. For the in situ pulse characterization, we implemented a photoionization-based FROG technique that is generally applicable to short VUV pulses down to few-femtosecond duration. The controlled generation of well-characterized few-cycle VUV pulses unlocks the study of coupled electronic and nuclear motion in electronically excited molecules with an unprecedented time resolution. Our approach is capable of performing pump–probe experiments in the VUV with few-femtosecond resolution. A series of such experiments on small molecules is currently underway in our laboratory. They will shed new light on early time dynamics in photo-excited molecules.

Methods

VUV generation

We send 37 fs pulses with 2 mJ energy from a Ti:sapphire chirped pulse amplifier system (Spectra Physics Spitfire Pro) operating at a repetition rate of 1 kHz into a 3-m-long SF-HCF (HCF1 in Fig. 1) with a core diameter of 450 µm. The capillary is differentially filled with argon gas at a backing pressure of 120 mbar. The spectrally broadened pulses are subsequently compressed to 10 fs duration by a set of chirped mirrors (PC70, Ultrafast Innovations). The light is then refocused into a second, 1.5-m-long SF-HCF of 250 µm core diameter (HCF2 in Fig. 1) where soliton self-compression and RDW emission take place. The waveguide geometry is chosen to generate the shortest RDW pulses at maximal pulse energy for our specific input laser parameters. The pulse energy entering the second capillary can be set by a variable attenuator consisting of a half-wave plate at the output of the laser (HWP in Fig. 1) and a broadband wire-grid polarizer placed between the capillaries before the chirped mirrors (WGP in Fig. 1). The maximum available pulse energy for inducing soliton dynamics is 680 µJ and the transmission of the evacuated SF-HCF is ~60%. We used HCF2 in an inverse pressure gradient mode, where we apply helium up to 2 bar pressure at the entrance of the waveguide, whereas the output is directly connected to a vacuum beamline having a residual helium pressure of 4–6 mbar. After collimation of the beam using an aluminium-coated concave mirror, the broadband soliton content was filtered out using two Brewster-angled silicon plates at an angle of incidence of 75°.

VUV spectrum and power measurement

Two motorized mirrors allow the beam to be sent to different diagnostics. The spectrum was measured using a McPherson 234/302 spectrograph equipped with 1,200-lines-per-millimetre Al + MgF2-coated flat-field grating and a CCD array (Andor DU920N). The spectrometer was calibrated using an Hg–Ar spectral line lamp. The power is measured by a calibrated volume absorber power meter (Ophir 3A-P) placed directly in the vacuum chamber. We measured the background signal remnants from the broadband soliton radiation caused by incomplete filtering. This was achieved by applying the full available laser power through HCF2 and adjusting the gas pressure to induce soliton self-compression, while staying just below the threshold of dispersive wave generation. In this way we measure 40 µW (corresponding to 40 nJ pulse energy), close to the power detection minimum.

The VUV eFROG apparatus

The VUV beam was split into two halves by two D-shaped aluminium mirrors, one of which was mounted on a piezo-driven nano-positioning stage (P-625.1U, Physik Instrumente GmbH). This allows us to have two time-shifted replicas of the VUV pulses with controllable delay. These were routed and focused into a chamber housing a VMI unit, with the focus at the centre of the apparatus. The steady-state gas pressure in the VMI during measurement was 2–5 × 10−5 mbar. Velocity maps were obtained by a microchannel plate and a phosphor screen for photoelectron visualization and a CCD camera for recording the images. Scans of the delay between the two replicas were performed while recording the VMI signal (see Supplementary Information for details on the procedure to extract a FROG trace from the pictures).

Phase retrieval from the eFROG traces

As the eFROG traces consist of an incoherent sum of two slightly shifted replicas due to the spin–orbit coupling in the detection gas, we chose a metaheuristic algorithm for the phase retrieval which does not make assumptions about the mathematical problem, thus allowing the implementation of the incoherent sum. Specifically, we implemented a differential evolution code36. To account for the effect of the spin–orbit splitting, the retrieved trace was calculated as follows:

First the contributions of each spin–orbit channel are calculated:

where ωi = IPi/ħ (i = 1, 2) are the optical frequencies corresponding to each of the ionization potentials and F(t) denotes the complex electric field of the pulse.

Then the kinetic energy spectrum of the photoelectrons at a given time delay τ is calculated by the incoherent sum of both contributions:

where \({\mathfrak{F}}\) denotes the Fourier transform, E the kinetic energy of the photoelectrons and C is the ratio of the yields of both channels. The value of C is also one of the parameters being retrieved as it is included in the properties of each individual of the differential evolution population. Finally, the trace is corrected by a delay-independent response function µ(E) which minimizes the difference between the two traces37:

This is necessary to correctly include the spectral sensitivity of the apparatus and the frequency dependence of the two-photon ionization process including the contributions of the AIS.

To achieve a quick convergence of the algorithm, the spectral phase is represented by six coefficients of its Taylor expansion, from the second order (GDD) up to the seventh-order term. The necessary number of coefficients was determined by comparing the retrieved phases obtained by running the algorithm with different numbers of coefficients. These coefficients are retrieved by the differential evolution algorithm. Each run starts with a population of 20 individuals all with random coefficients. For each individual a trace was calculated and compared to the measured one by computing the RMS of the residuals37. This value was then used to rank the individual within the population. For all the presented data, 10 retrievals were performed for each measured eFROG trace for statistics.

In Fig. 3e,k we compare the input and retrieved pulse shapes. For a quantitative comparison we calculate the rms field error38

where F0 is the known input, and F is the retrieved electric field, both sampled by N points. Before calculation the amplitudes, the carrier envelope phases and the group delays of the electric fields are matched37.

Quantum mechanical code for calculating the kinetic energy spectrum of the photoelectrons

The TDSE calculations were performed within the time-dependent configuration-interaction singles (TD-CIS) ansatz, wherein single excitations are allowed from a reference state, in the present case from the Hartree–Fock ground state. Our implementation of TD-CIS is described in refs. 39,40. To account for quasirelativistic effects, we employ a small-core relativistic effective-core potential designed by Peterson and colleagues41, which yields correct spin–orbit splitting albeit an ionization potential that is slightly too low (see Extended Data Table 2). The calculations were performed on a spherical grid, where the radial grid extended to 300 bohr, and the grid points were distributed according to

where ρmin, ρmax and α were chosen to be 0.12 bohr, 0.17 bohr and 0.3, respectively. The spin–angular dimensions were expanded using all spinor spherical harmonics (see section 7.2 of ref. 42) for which the orbital angular momentum l ≤ 10. As we consider linear polarization only, we may use the restriction Δmj = 0 for a total of 164 spin–angular partial waves, given that we also limited excitation to occur only from ns2 np6. To avoid reflections at the edge of the computational box, we employ the complex-absorbing potential by Manolopoulos43, spanning the last 231.77 bohr of the box, and with a design parameter δ = 0.20866.

The retrieval algorithm yields the electric field amplitude discretized on a uniform grid: \(\{{t}_{n},{F}_{c}\left({t}_{n}\right)\}\), where \({t}_{n}={t}_{0}+n\delta t\) and \({F}_{c}\left({t}_{n}\right){\mathbb{\in }}{\mathbb{C}}\) are complex due to the spectral nature of the algorithm. The TDSE calculations need the vector potential \(A\left(t\right)\) (which is related to the electric field as \(F\left(t\right)=-{\partial }_{t}A\left(t\right)\)), and we compute this by integration in the Fourier domain. Furthermore, a time grid that is finer than the one provided by the retrieval algorithm is necessary (we take 10 steps per atomic unit of time \(\approx\) 413 steps per femtosecond), and we employ cubic Hermite interpolation for that purpose. Finally, the electric field amplitude and vector potentials need to be real quantities, so we arbitrarily choose the real part of the interpolated functions: \(F\left(t\right){\mathfrak{=}}{\mathfrak{R}}{\mathfrak{\{}}{F}_{c}\left(t\right)\}\), \(A\left(t\right){\mathfrak{=}}{\mathfrak{R}}{\mathfrak{\{}}{A}_{c}\left(t\right)\}\).

The retrieved pulse shape and a delayed copy are fed as input to the TDSE calculations, and the resulting photoelectron spectrum is computed using the surface-flux techniques39,44,45. This calculation is repeated for a set of delays in the –5 fs to 5 fs range. As for even very large pump–probe delays, the two-photon ionization signal is non-negligible, we subtract a background taken as the photoelectron spectrum resulting from a 20 fs pump–probe delay calculation. To approximately account for the phase slip across the spatial profile of the pulse due to the noncollinear geometry, we repeat the delay scan, applying a carrier–envelope phase (CEP) shift to the delayed pulse replica. The fields used in the calculation are thus

where \(\tau\) is the time delay and \(\theta\) is the applied CEP. The resultant delay scans for four different CEP values are shown below, as well as their average.

Measurement of the thickness of the fused silica plate

The knowledge of the sample thickness is necessary for the calculation of the chirp introduced by a fused silica plate. As the plate is only a few micrometres thick, we used spectral interferometry to precisely determine its thickness. The spacing of the spectral fringes arising from the interference between the front and back reflections is measured when the plate was illuminated by the Ti:sapphire laser oscillator.

Data availability

Data sets shown in the figures are available in the figshare repository under the link https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29835218.

Code availability

The full theoretical and technical details on the atomic TD-CIS code are published in Physical Review A via https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevA.106.042806 (ref. 41). The computer implementation of the code is proprietary, and is therefore not generally available. It may be supplied on a case-by-case basis on reasonable request to S.C. (stefanos@mbi-berlin.de). The other codes written by the authors for preparing the presented data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Krausz, F. & Ivanov, M. Attosecond physics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 81, 163–234 (2009).

Lépine, F., Ivanov, M. Y. & Vrakking, M. J. J. Attosecond molecular dynamics: fact or fiction? Nat. Photon. 8, 195–204 (2014).

Suzuki, T. Time-resolved photoelectron spectroscopy of non-adiabatic electronic dynamics in gas and liquid phases. Int. Rev. Phys. Chem. 31, 265–318 (2012).

Durfee, C. G., Backus, S., Kapteyn, H. C. & Murnane, M. M. Intense 8-fs pulse generation in the deep ultraviolet. Opt. Lett. 24, 697–699 (1999).

Kida, Y., Liu, J., Teramoto, T. & Kobayashi, T. Sub-10 fs deep-ultraviolet pulses generated by chirped-pulse four-wave mixing. Opt. Lett. 35, 1807–1809 (2010).

Baum, P., Lochbrunner, S. & Riedle, E. Tunable sub-10-fs ultraviolet pulses generated by achromatic frequency doubling. Opt. Lett. 29, 1686–1688 (2004).

Baum, P., Lochbrunner, S. & Riedle, E. Generation of tunable 7-fs ultraviolet pulses: achromatic phase matching and chirp management. Appl. Phys. B 79, 1027–1032 (2004).

Kosma, K., Trushin, S. A., Schmid, W. E. & Fuss, W. Vacuum ultraviolet pulses of 11 fs from fifth-harmonic generation of a Ti:sapphire laser. Opt. Lett. 33, 723–725 (2008).

Graf, U. et al. Intense few-cycle light pulses in the deep ultraviolet. Opt. Express 16, 18956–18963 (2008).

Reiter, F. et al. Generation of sub-3 fs pulses in the deep ultraviolet. Opt. Lett. 35, 2248–2250 (2010).

Bothschafter, E. M. et al. Collinear generation of ultrashort UV and XUV pulses. Opt. Express 18, 9173–9180 (2010).

Galli, M. et al. Generation of deep ultraviolet sub-2-fs pulses. Opt. Lett. 44, 1308–1311 (2019).

Cregan, R. F. et al. Single-mode photonic band gap guidance of light in air. Science 285, 1537–1539 (1999).

Benabid, F., Knight, J. C., Antonopoulos, G. & Russell, P. S. J. Stimulated Raman scattering in hydrogen-filled hollow-core photonic crystal fiber. Science 298, 399 (2002).

Hasegawa, A. & Tappert, F. Transmission of stationary nonlinear optical pulses in dispersive dielectric fibers. 1. Anomalous dispersion. Appl. Phys. Lett. 23, 142–144 (1973).

Mollenauer, L. F., Stolen, R. H. & Gordon, J. P. Experimental observation of picosecond pulse narrowing and solitons in optical fibers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 45, 1095–1098 (1980).

Mak, K. F., Travers, J. C., Hölzer, P., Joly, N. Y. & Russell, P. S. J. Tunable vacuum-UV to visible ultrafast pulse source based on gas-filled Kagome-PCF. Opt. Express 21, 10942–10953 (2013).

Im, S. J., Husakou, A. & Herrmann, J. High-power soliton-induced supercontinuum generation and tunable sub-10-fs VUV pulses from kagome-lattice HC-PCFs. Opt. Express 18, 5367–5374 (2010).

Joly, N. Y. et al. Bright spatially coherent wavelength-tunable deep-UV laser source using an Ar-filled photonic crystal fiber. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 203901 (2011).

Russell, P. S. J., Hölzer, P., Chang, W., Abdolvand, A. & Travers, J. C. Hollow-core photonic crystal fibres for gas-based nonlinear optics. Nat. Photon. 8, 278–286 (2014).

Köttig, F., Tani, F., Biersach, C. M., Travers, J. C. & Russell, P. S. J. Generation of microjoule pulses in the deep ultraviolet at megahertz repetition rates. Optica 4, 1272–1276 (2017).

Travers, J. C., Grigorova, T. F., Brahms, C. & Belli, F. High-energy pulse self-compression and ultraviolet generation through soliton dynamics in hollow capillary fibres. Nat. Photon. 13, 547–554 (2019).

Brahms, C. & Travers, J. C. HISOL: High-energy soliton dynamics enable ultrafast far-ultraviolet laser sources. APL Photon. 9, 050901 (2024).

Brahams, C., Belli, F. & Travers, J. C. Resonant dispersive wave emission in hollow capillary fibers filled with pressure gradients. Opt. Lett. 45, 4456–4459 (2020).

Reduzzi, M. et al. Direct temporal characterization of sub-3-fs deep UV pulses generated by resonant dispersive wave emission. Opt. Express 31, 26854–26864 (2023).

Trebino, R. Frequency-Resolved Optical Gating: The Measurement of Ultrashort Pulses (Springer, 2000).

Sekikawa, T., Katsura, T., Miura, S. & Watanabe, S. Measurement of the intensity-dependent atomic dipole phase of a high harmonic by frequency-resolved optical gating. Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 193902 (2002).

Kosuge, A. et al. Frequency-resolved optical gating of isolated attosecond pulses in the extreme ultraviolet. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 263901 (2006).

Nagy, T., Forster, M. & Simon, P. Flexible hollow fiber for pulse compressors. Appl. Opt. 47, 3264–3268 (2008).

Eppink, A. T. J. B. & Parker, D. H. Velocity map imaging of ions and electrons using electrostatic lenses: application in photoelectron and photofragment ion imaging of molecular oxygen. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 68, 3477 (1997).

Brahms, C. & Travers, J. C. Luna.jl. Zenodo https://zenodo.org/badge/latestdoi/190623784 (2022).

Kitamura, R., Pilon, L. & Jonasz, M. Optical constants of silica glass from extreme ultraviolet to far infrared at near room temperature. Appl. Opt. 46, 8118–8133 (2007).

Kotsina, N., Brahms, C., Jackson, S. L., Travers, J. C. & Townsend, D. Spectroscopic application of few-femtosecond deep-ultraviolet laser pulses from resonant dispersive wave emission in a hollow capillary fibre. Chem. Sci. 13, 9586–9594 (2022).

Lee, J. P. et al. Few-femtosecond soft X-ray transient absorption spectroscopy with tuneable DUV–vis pump pulses. Optica 11, 1320–1323 (2024).

Wanie, V. et al. Capturing electron-driven chiral dynamics in UV-excited molecules. Nature 630, 109–115 (2024).

Escoto, E., Tajalli, A., Nagy, T. & Steinmeyer, G. Advanced phase retrieval for dispersion scan: a comparative study. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 35, 8–19 (2018).

Geib, N. C., Zilk, M., Pertsch, T. & Eilenberger, F. Common pulse retrieval algorithm: a fast and universal method to retrieve ultrashort pulses. Optica 6, 495–505 (2019).

Dorrer, C. & Walmsley, I. A. Accuracy criterion for ultrashort pulse characterization techniques: application to spectral phase interferometry for direct electric field reconstruction. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 19, 1019–1029 (2002).

Carlström, S., Spanner, M. & Patchkovskii, S. General time-dependent configuration-interaction singles. I. Molecular case. Phys. Rev. A 106, 043104 (2022).

Carlström, S., Bertolino, M., Dahlström, J. M. & Patchkovskii, S. General time-dependent configuration-interaction singles. II. Atomic case. Phys. Rev. A 106, 042806 (2022).

Peterson, K. A., Figgen, D., Goll, E., Stoll, H. & Dolg, M. Systematically convergent basis sets with relativistic pseudopotentials. II. Small-core pseudopotentials and correlation consistent basis sets for the post-d group 16–18 elements. J. Chem. Phys. 119, 11113–11123 (2003).

Varshalovich, D. A., Moskalev, A. N. & Khersonskii, V. K. Quantum Theory of Angular Momentum (World Scientific, 1988).

Manolopoulos, D. E. Derivation and reflection properties of a transmission-free absorbing potential. J. Chem. Phys. 117, 9552–9559 (2002).

Tao, L. & Scrinzi, A. Photo-electron momentum spectra from minimal volumes: the time-dependent surface flux method. New J. Phys. 14, 013021 (2012).

Morales, F., Bredtmann, T. & Patchkovskii, S. iSURF: a family of infinite-time surface flux methods. J. Phys. B 49, 245001 (2016).

Saloman, E. B. Energy levels and observed spectral lines of xenon, Xe I through Xe LIV. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 33, 765–921 (2004).

Hansen, J. E. & Persson, W. Revised analysis of singly ionized xenon, Xe II. Phys. Scr. 36, 602 (1987).

Acknowledgements

We thank O. Kornilov (MBI) and S. Kleinert (Leibniz Universität Hannover) for fruitful discussions concerning the vacuum beamline and the phase retrieval algorithm, respectively. This work was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) (NA1102/3-1, project number 431657459) in the frame of the call ANR-DFG NLE (project INTRALAS). A.R acknowledges support by the Leibniz Gemeinschaft (SAW-K380-2021). M.Y.I. acknowledges support by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) (IV152/11-1, project number: 545591821).

Funding

Open access funding provided by Max-Born-Institut für Nichtlineare Optik und Kurzzeitspektroskopie (MBI) im Forschungsverbund Berlin e.V.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.N., A.M.-B. and A.R. conceived this work. J.R.C.A. and T.N. built the VUV source. M.K. proposed the eFROG method. J.R.C.A., M.K. and R.D. with the help of A.R. performed the eFROG measurements. J.R.C.A., M.K. with the help of T.W. processed the data. J.R.C.A. wrote the phase retrieval algorithm and evaluated the eFROG traces. S.C. with the help of S.P. performed the TDSE simulations. M.J.J.V., M.Y.I., A.R. and T.N. interpreted and analysed the results. T.N., A.R., J.R.C.A. and M.K. drafted the manuscript and all authors participated in the discussion of the results, and in the editing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Photonics thanks Jens Limpert and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Sections 1–4 containing: Figs. 1–4, Table 1, References and Discussion.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Andrade, J.R.C., Kretschmar, M., Danylo, R. et al. Temporal characterization of tunable few-cycle vacuum ultraviolet pulses. Nat. Photon. 19, 1240–1246 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-025-01770-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41566-025-01770-6

This article is cited by

-

Plasma lens for focusing attosecond pulses

Nature Photonics (2025)