Abstract

Increasing numbers of transgender and nonbinary youth are now accessing gender-affirming medical interventions, which have been demonstrated to improve health and well-being. This Perspective addresses how the needs of transgender and nonbinary youth, up to age 18, can be addressed through individualized gender-embodiment care. We first review standard medical therapies, including gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues, 17β-oestradiol, testosterone, steroidal antiandrogens and progestins, followed by presenting novel approaches to individualizing gender healthcare for transgender and nonbinary youth, consisting of selective oestrogen receptor modulators, 5α-reductase inhibitors, aromatase inhibitors and non-steroidal antiandrogens. Ethical guidance for off-label prescribing is provided, grounded in the principles of evidence, benefit, safety, respect, care, communication, transparency, equity and innovation. These ethical principles are applied in three clinical scenarios in which off-label therapies are considered. We conclude that standard medical therapies are ethically justified and that novel therapies can be ethically acceptable when carefully considered in the context of an individual youth’s care plan and taking into account the available theoretical, clinical and research evidence as well as the potential benefits and potential risks. In keeping with the principle of innovation, we encourage clinicians and researchers to share evidence of medical innovations that support the gender health of transgender and nonbinary youth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Evidence-based approaches to supporting transgender and nonbinary (TNB) youth include gender-affirming psychosocial support, non-medical options (for example, names, pronouns, chest binding), pubertal suppression and hormone therapy1. Gender-affirming medical interventions (such as pubertal suppression and hormone therapy) are effective in improving the health and well-being of TNB youth2,3,4,5,6,7,8. TNB youth might or might not require gender-affirming medical interventions based on their individual gender-embodiment goals (for example, development of facial hair or breasts; cessation of menses)9. Nonetheless, a small but increasing number of TNB youth are seeking access to this care10,11.

International guidelines provide evidence-based approaches to psychosocial, medical and surgical care for TNB people1,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19. The standards of care from the World Professional Association for Transgender Health specifically discuss adolescent care and highlight the importance of multidisciplinary team care, comprehensive biopsychosocial assessment, psychosocial support and, when indicated, gender-affirming medical interventions1. It is beyond the scope of this article to address psychosocial care and assessment regarding readiness for gender-affirming medical interventions; readers wishing to learn more should consult relevant references1,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19. The purpose of this paper is to provide an overview of standard medical therapies and discuss potential ethical uses of novel medical therapies to address the gender-embodiment goals9 of TNB youth up to age 18 years.

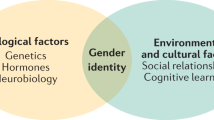

The following terms are central to the discussion of healthcare for TNB youth. ‘Transgender’ is an umbrella term describing experiences of gender that are not aligned with sociocultural expectations based on the sex or gender assigned to a person, inclusive of binary and nonbinary genders. ‘Nonbinary’ encompasses genders that are not solely female and/or woman or male and/or man (for example, genderqueer, genderfluid)9. ‘Assigned female at birth’ (AFAB) and ‘assigned male at birth’ (AMAB) indicate assignment of sex to an infant on the basis of physical characteristics (such as external genitalia). ‘Gender health’ is the ability to live freely and comfortably in one’s gender20, and gender embodiment is the process of making one’s internal sense of gender visible (also called transition or affirmation)9. ‘Gender-affirming care’ is an overarching term for healthcare provided in a manner that is supportive of a person’s self-identified gender. ‘Gender-affirming medical interventions’ (such as pubertal suppression and hormone therapy) are specific forms of medical care that support gender embodiment. ‘Endocisnormativity’ describes assumptions or biases that only people who are both cisgender and of either male or female sex are ‘normal’9.

Standard gender-affirming medical interventions for TNB youth

An established body of evidence supports gender-affirming pubertal suppression and hormone therapy for TNB youth who have entered puberty. Since the 1990s, studies have shown that gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues (GnRHa) can be safely and effectively prescribed to TNB youth following the onset of puberty (that is, from Tanner Stage 2) to suppress endogenous sex hormones and prevent unwanted development of secondary sex characteristics3,8,21,22 (Table 1). Multiple studies have confirmed safety in terms of cardiovascular and metabolic health among TNB youth whose treatment included GnRHa either alone or with hormone therapy23,24,25,26,27. Some studies have shown differences in body composition among TNB youth who have accessed GnRHa and hormone therapy when compared with matched controls25,27. TNB youth who have accessed pubertal suppression (alone or with additional gender-affirming medical interventions) report satisfaction with treatment as well as improved well-being, comfort and social relationships, and reductions in suicidality, self-harm and depressive symptoms3,21,28,29,30,31. TNB adults who were able to access pubertal suppression as youth report lower levels of lifetime suicide ideation than their TNB peers who wanted but were unable to access this treatment32. Additional studies are needed to provide guidance on how long GnRHa monotherapy can safely be prescribed without problematic long-term effects on bone health and to understand how long-term GnRHa therapy affects neurocognitive development1,33,34.

Gender-affirming hormone therapy is prescribed to TNB youth to effectively support gender-embodiment goals such as testosterone to increase muscle mass and deepen the voice and oestrogen to soften the skin and develop breast or chest tissue35,36,37 (Table 1). Research shows that kidney function, liver function and blood pressure in TNB youth taking gender-affirming hormone therapy typically remain in the normal ranges for a person’s experienced gender24,35,38,39,40,41,42,43. TNB youth accessing gender-affirming hormone therapy report lowered anxiety, depression and suicidality as well as improved psychological well-being, social satisfaction, self-efficacy and life satisfaction2,3,8,44. When compared with TNB youth not taking hormone therapy, TNB youth accessing hormone therapy reported reduced severity of anxiety and depression, alongside less body-related distress45.

Steroidal antiandrogens, such as spironolactone and cyproterone acetate (Table 1), can also suppress endogenous testosterone secretion and/or action and are frequently used as adjunctive therapy to oestrogen-based therapy in people AMAB. Although steroidal antiandrogens are less potent than GnRHa, they are generally more affordable and are commonly used when GnRHa agents are unavailable, too expensive (for example, due to lack of insurance coverage) or likely to be of reduced benefit (such as after puberty has ended)1,46. Both spironolactone and cyproterone acetate can cause some breast or chest tissue development; although cyproterone acetate is associated with greater suppression of testosterone production than spironolactone, it is not available in some jurisdictions (such as the USA)42,47. Various progestins (such as oral or intramuscular medroxyprogesterone acetate), progestin-only pills (such as norethindrone acetate) and levonorgestrel-containing intrauterine devices can be used as menstrual management methods in place of a GnRHa for those patients presenting in late puberty48. Medroxyprogesterone has also been used in place of a GnRHa for pubertal suppression in TNB youth AMAB and AFAB49.

Established international standards and guidelines include protocols for gender-affirming medical interventions for youth and adults1,12. These protocols have historically been largely endocisnormative, reflective of binary conceptualizations of gender; for example, recommendations within guidelines from the Endocrine Society include gradually increasing oestrogen or testosterone every 6 months for TNB youth until reaching adult doses12. The current World Professional Association for Transgender Health Standards of Care (version 8) support and supplement the Endocrine Society’s protocols, with new guidance on addressing non-endocisnormative gender-embodiment goals via individually customized hormone regimens1. For instance, some people’s gender-embodiment goals can best be addressed via hormone therapy with lower-than-conventional doses (colloquially referred to as ‘low-dose’ or ‘microdosing’) of testosterone or oestrogen or with a short-term regimen that is discontinued once embodiment goals (for example, voice deepening) are achieved9 (Table 1).

Endocisnormative bias, evidence and misinformation

Before beginning our description of innovative medical therapies, the potential influence of endocisnormative bias, the available evidence and the role of misinformation in the provision of gender-affirming care to TNB youth should be considered. Despite expansion of evidence-based gender-affirming care over the past three decades, endocisnormativity remains prevalent in healthcare settings9. Biases about TNB people and gender-affirming care can affect healthcare practice, research and policy (such as restricting innovation and access to care), making this an ethically important issue50,51,52. When endocisnormative bias is enacted by policy-makers or healthcare providers (for example, through denial of care, discriminatory treatment or lack of accessible care), this can negatively affect the well-being of TNB youth53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62. Gender minority stress is a framework for understanding the psychological effects of trans-specific stigma (including external stressors such as gender-based discrimination and internal stressors such as negative future expectations) on TNB people63,64,65. TNB youth who have negative healthcare experiences (such as disrespectful treatment or breaches of confidentiality) might be reluctant to seek care in the future61,62. Additionally, access to evidence-based gender-affirming care is presently being restricted, both directly through guidelines and legislation (for example, prohibiting or restricting provision of care or insurance coverage in the USA) and indirectly through intimidation and endocisnormative misinformation52,66,67,68.

Standards for gender-affirming care are grounded in and regularly updated on the basis of an expanding body of evidence1,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,69. Sound reviews of clinical approaches, which draw on the expertise of clinicians providing gender-affirming medical interventions for TNB youth as well as extant and emerging methodologically sound research, are necessary to inform practice. In the past decade, gender-affirming medical interventions have become increasingly politicized and growing public attention is being paid to varying views expressed by healthcare providers and policy-makers about the quality of existing research evidence and approaches to supporting TNB youth. We note that there are different approaches to reviewing medical literature, including evaluating research evidence using ranking systems that privilege randomized controlled trials (RCTs) as the highest quality evidence; however, in some areas of healthcare, such as paediatric care and gender-affirming care, the limitations of RCTs are widely recognized70,71,72. As noted previously in this article, evidence supports the effectiveness and safety of gender-affirming medical interventions for TNB youth; however, reviewing the evidence with tools that privilege RCTs can result in methodologically sound observational studies being labelled as ‘low’ quality evidence71. Among audiences not familiar with evidence-ranking systems or aware that observational evidence is widely used to develop standards for medical care, these findings can be misinterpreted71.

Endocisnormative misinformation messages are of growing concern in the field of gender healthcare52,73. Health misinformation messages often begin with true information that is modified (such as by adding or removing key components) such that the information shared is believable but false74. For example, misinformation messages about the evidence base for gender-affirming medical interventions might refer to published articles, including outdated or retracted studies, while falsely reporting that these interventions are unsafe or unsupported by evidence52. Another example of endocisnormative misinformation relates to a purported inability of any TNB youth to make decisions about gender-affirming medical interventions, a false message spread despite evidence documenting the ability of some minor youth, including TNB youth, to demonstrate capacity to make medical decisions75,76,77,78,79. Additionally, although nonbinary genders have been documented throughout history, some misinformation messages promote a false idea that nonbinary genders are a new phenomenon80. Attempting to hold gender-affirming care to a different standard of evidence than other forms of healthcare, holding TNB youth to a different measure of decisional capacity or outright invalidating nonbinary genders can all further exacerbate inequities faced by TNB youth. In this Perspective, we aim to centre the well-being of TNB youth and counter endocisnormativity through the presentation of evidence and guidance to support individualized, ethically sound and innovative care to address gender-embodiment goals of TNB youth.

Innovative medical therapies

Innovation in medicine begins with a novel idea that potentially carries more benefit than the status quo81. One common pathway to medical innovation is off-label prescribing, which refers to prescribing a medication for a purpose other than one that is approved by the relevant regulatory body, including for a different indication, dose, route of administration or population82,83,84. The purpose of off-label prescribing is to benefit the patient when approved medications are not available or appropriate84,85. According to a 2009 review article, “Most off-label prescribing has clear therapeutic goals, and in certain practice areas, off-label prescribing is both extremely common and necessary”86. For example, gender-affirming hormone therapies (that is, GnRHa, antiandrogens, testosterone, oestrogens and progestins) are prescribed to support gender-embodiment goals on the basis of theoretical, clinical and research evidence of safety and benefit, as documented within internationally recognized clinical guidelines; however, as pharmaceutical companies have not sought approval for gender-affirming indications of these medications, such prescriptions are off-label1,12,87. Off-label prescribing on the basis of theoretical, clinical and research evidence of safety and benefit is also particularly common in paediatric medicine, accounting for 10.8–72% of prescriptions across various settings and due, in large part, to the lack of enrolment of children in clinical trials conducted to establish safety and efficacy for drug approval88,89.

The use of GnRHa in TNB youth is an example of innovation in gender-embodiment care. GnRHa has a track record of safe and effective use with children experiencing central precocious puberty90,91,92. In 2006, a protocol was published for prescribing this medication in a novel way to a new population (youth with ‘gender identity disorder’), for the same purpose of temporarily suppressing puberty93. On the basis of research documenting the safety and effectiveness of this GnRHa protocol, this innovation has become an integral part of international standards for gender-affirming care for TNB youth1,3,12,28,29,30,31,32,94,95.

Novel medical therapies proposed for TNB youth

Several novel medical therapies have been proposed to achieve effects that are more difficult to attain with standard pubertal suppression or testosterone-based or oestrogen-based therapies96,97. In this section, we review the mechanisms of action, on-label indications, side effects and potential uses in TNB populations of four novel medical therapies for gender-affirming care. Additional details on the effects of these medications and postulated benefits for TNB youth are presented in Table 2. These medications are familiar to most endocrinologists as they primarily affect either the synthesis or end-organ actions of sex hormones. Most are routinely used as short-term treatments for specific medical conditions, and their innovative use as gender-affirming medical interventions would be off-label.

Selective oestrogen receptor modulators

Selective oestrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) are compounds with mixed agonist and antagonist action on oestrogen receptors (ERs), with variable tissue specificities98. For example, tamoxifen and raloxifene, two commonly used SERMs, have oestrogenic effects in bone but little oestrogenic effect in breast98. SERMs are thought to act via their interference in the formation of ERα and ERβ homodimers and heterodimers, thus altering the binding of these dimers with cell-specific coactivators and corepressors to oestrogen response elements in target genes. Target-tissue specificity therefore depends on the mix of ER isoforms and cofactors present in the cell99. SERMs are primarily used in people being treated for breast cancer (reflecting their antagonistic action in the breast) and for the treatment or prevention of osteoporosis (reflecting their agonistic action in bone)98. They are also used off-label to treat children AMAB with gynaecomastia100. SERMs could potentially be prescribed for TNB youth AMAB on testosterone-suppression therapies who would like some of the effects of oestrogens (such as the increase in skin elasticity and the shift in adipose tissue distribution seen with raloxifene in individuals in postmenopause, with preservation of bone mineral content) while minimizing breast or chest tissue development101,102,103. Side effects of SERMs that have been previously documented in other contexts include hair loss, nausea, mood changes and menopausal symptoms. Findings from a 2008 meta-analysis indicate a 54% increase in the risk for deep vein thrombosis and a 91% increase in the risk for pulmonary embolism among people in postmenopause taking the SERM raloxifene when compared with control groups104. The risk of developing dysglycaemia is increased by 31%105, and hypertriglyceridaemia with hepatic steatosis has been described106. Use of SERMs in paediatric patients is limited but they seem to be well tolerated100. SERMs can elevate levels of testosterone107, which could lead to unwanted effects in TNB youth AMAB.

5α-Reductase inhibitors

5α-Reductase inhibitors (5αRIs) inhibit the action of 5α-reductase (primarily isoform 2), an enzyme that causes the conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone (DHT). By inhibiting this enzyme, these drugs reduce serum levels of DHT by 70% (finasteride) to 90% (dutasteride)108. 5αRIs are primarily used to treat benign prostatic hyperplasia and prostatic cancer108. 5αRIs in lower doses are also used to reduce androgen-dependent hair loss and, in people AFAB, to treat hirsutism by reducing DHT formation in skin and hair109. For TNB youth AFAB who are receiving testosterone, the addition of 5αRIs alongside testosterone therapy has the theoretical advantage of allowing effects of testosterone on voice and libido while minimizing the concurrent DHT-dependent hair growth on the face and body and reducing hair loss on the scalp110. Theoretically, genital growth can be caused by DHT110, so if this is not a desired effect of testosterone, it can potentially be decreased with the addition of 5αRIs. For people AMAB who are taking oestrogens but who would like to preserve erectile function with some endogenous or exogenous testosterone, the co-use of 5αRIs could theoretically ameliorate some of the DHT-related effects of testosterone on facial, scalp and body hair110. The reported side effects of 5αRIs include decreased libido, increased sexual dysfunction, and increased risk of anxiety, depression and suicidality109,111. The use of 5αRIs in paediatrics is extremely limited. The use of 5αRIs can result in increases in testosterone and oestradiol levels in TNB youth AMAB, probably because blockage of 5α-reduction of testosterone leaves more unconverted hormone available for aromatization to oestrogen109, which might result in unwanted effects.

Aromatase inhibitors

This class of medication inhibits the action of aromatization of androgens (androstenedione and testosterone) to oestrogens (oestrone and oestradiol, respectively). The use of aromatase inhibitors can lead to increased testosterone levels112. Anastrozole and letrozole are commonly used aromatase inhibitors. Aromatase inhibitors are primarily used as adjuvant therapy in the treatment of aggressive breast cancer112. Because they can delay epiphyseal fusion (closure of growth plates), aromatase inhibitors are also used to try to preserve final height in children with gonadotropin-independent isosexual precocity (such as McCune–Albright syndrome, male-limited gonadotropin-independent precocious puberty (also known as testotoxicosis) or congenital adrenal hyperplasia) and in children AMAB with short stature113. For TNB youth AFAB who have not yet achieved skeletal maturity and are on testosterone therapy, aromatase inhibitors could potentially increase adult height, although the benefit would probably be modest113. Other theoretical uses include the minimization of residual endogenous oestradiol production (which could aid with menstrual cessation) and prevention of oestrogenic effects of testosterone therapy via peripheral aromatization in adipose tissue (more common in people with obesity)114. One potential use of aromatase inhibitors for people AMAB is to inhibit the breast or chest tissue development that might occur when taking spironolactone or cyproterone acetate, even without concurrent oestradiol use115. The use of aromatase inhibitors in children AMAB has been well tolerated; however, they are known to cause menopausal symptoms in adults AFAB. Aromatase inhibitors can elevate testosterone levels in all patients113, which could be counterproductive in TNB youth AMAB.

Non-steroidal antiandrogens

Non-steroidal antiandrogens (NSAAs) are direct inhibitors of the androgen receptor and include bicalutamide and flutamide (flutamide is now rarely used owing to the risk of hepatotoxicity). Because NSAAs block the feedback of testosterone on gonadotropin secretion, the use of an NSAA alone can lead to elevations of testosterone and oestrogen levels116. The primary use of NSAAs is in the treatment of prostate cancer116. Less common indications include hirsutism, balding and acne in people AFAB117 as well as testotoxicosis in young people AMAB118. Bicalutamide has been used to suppress puberty in trans youth AMAB for whom a GnRHa was not available; this use of bicalutamide can lead to some breast or chest development, even without concurrent use of oestrogen119. In adults AMAB who choose not to use oestrogens, NSAA therapy has been proposed as a method to decrease the effects of endogenous testosterone without compromising bone health; however, blockade of normal androgen feedback at the hypothalamic–pituitary level will result in a rise in levels of gonadotropins and thus also of sex hormones, which could lead to unwanted oestrogen effects such as breast or chest tissue growth120. Although generally well tolerated, flutamide and especially bicalutamide can lead to hepatotoxicity, which can be fulminant116,121. Interstitial pneumonitis has also been described with the use of bicalutamide122 (Table 2).

Ethical guidance for off-label prescribing

Guiding principles from the extant literature on the ethics of off-label prescribing can be applied in the context of novel medical therapies for TNB youth. Standard off-label prescribing practices in paediatric care, gender-affirming care and other areas of medicine align with guiding ethical principles of evidence, benefit, safety, respect, care, communication, transparency, equity and innovation, defined as follows82,83,84,123,124,125,126,127,128,129. Evidence: grounding treatment decisions in the best available theory, clinical expertise and research82,83,84,87,123,124. Benefit: providing therapies that are likely to be effective82,83,84,123,124,125,127. Safety: providing therapies for which the likelihood and magnitude of benefit outweigh the risk of adverse events84,123,125,127. Respect: engaging with patients to understand their treatment goals and honouring their autonomy to participate in decision-making about treatment options86,123,126,128,129. Care: demonstrating kindness, attention and empathy in providing individually customized care83,124,128. Communication: sharing information necessary for informed decision-making with the patient in ways that are developmentally and culturally accessible97,123,126. Transparency: providing open, honest communication about possible treatment options and limitations86,97,123. Equity: providing fair and just opportunities for access to quality care in order to reach the highest attainable standard of health86,130. Innovation: developing new theoretical, clinical and research evidence to improve healthcare86,125.

These guiding ethical principles are considered within the context of an individual patient’s circumstances (for example, medical information, gender-embodiment goals or contextual factors). Some principles might be weighed more heavily than others in making decisions about an individual’s care but all remain relevant in consideration of off-label prescribing of standard and novel medical therapies for TNB youth. For example, healthcare providers should respectfully engage with youth to understand their gender-embodiment goals and demonstrate care in working towards individualized care plans. They should communicate openly and be transparent about options. Once a healthcare provider determines that standard medical therapies will not be adequate to address embodiment goals, novel therapies can be considered. This approach is guided by the principle of equity, to support the human right to the highest attainable standard of health79,131. The principle of innovation is tied to equity, as novel, evidence-based approaches can more readily be developed to address health disparities when equity in funding for gender healthcare and research is achieved.

The theoretical, clinical and research evidence and potential benefits and safety of specific novel therapies should be weighed and balanced within the context of an individual’s comprehensive care plan. Inherent in analysing off-label novel therapies is acknowledgement that the evidence for prescribing a medication for the specific indication, dose, route of administration and population might not be robust, and evidence should be extrapolated from related research83,84,87,124,128. Off-label options are deemed ethically acceptable when, in the judgement of the healthcare provider, there is sufficient theoretical, clinical and/or research evidence to support probable benefit that outweighs the potential risks to the individual and that the therapy does not carry a high likelihood of significant harm. Ethical analysis can be supported through the following guidance, drawn from existing literature on off-label prescribing, bias and misinformation: review available theoretical, clinical and research evidence82,83,84,87,123; evaluate the likelihood and magnitude of potential benefits for the individual82,83,84,123,124,125,127; evaluate the likelihood and magnitude of potential risks to the individual84,123,125,127; consider how biases and misinformation could influence information used in conducting ethical analyses50,51,52,66; and consult colleagues, organizational policies and/or committees, professional standards, ethicists, and ethics committees81,84,86,97,125. Application of these strategies in the context of individualized care planning for TNB youth can ensure sufficient information has been gathered to analyse the ethical acceptability of novel medical therapies.

When ethically acceptable novel medical therapies are offered to a patient, the healthcare provider should be transparent in communicating information about the available evidence, likelihood of specific benefits and risks, the off-label nature of a therapy, and how ethical acceptability or unacceptability was determined. The feasibility of pursuing a novel medical therapy (such as costs) might need to be discussed in the context of informed decision-making. In the absence of therapies that will fully support a youth’s embodiment goals, standard or ethically acceptable novel medical therapies that will support the youth to live as comfortably as possible in their gender should be presented. If a novel therapy is prescribed, the effects should be carefully monitored and documented. In keeping with the principle of innovation, healthcare providers should, with permission of the youth (and parent or guardian, if applicable), share emerging evidence related to innovative approaches with other healthcare providers and researchers.

Clinical scenarios

The following fictional clinical scenarios highlight situations in which standard medical therapies might not adequately support a youth’s gender-embodiment goals. The scenarios are presented in text, followed by summaries of how to ethically approach each scenario based on individual embodiment goals, current evidence, benefits and safety of the proposed therapies and the expertise of the author group. See Boxes 1, 2 and 3 for detailed information about potential therapeutic options and ethical considerations. Novel medical therapies are considered on the basis of embodiment goals and not on the presence of a binary or nonbinary gender; therefore, the relevant physiological information and gender-embodiment goals of each youth are presented, rather than their gender or their sex assigned at birth. In practice, the clinical and ethical judgement of healthcare providers working with an individual youth is key in deciding whether to offer a novel therapy. As with standard medical therapies, novel interventions would be a component of a comprehensive care plan, which often includes psychosocial support and non-medical options (for example, chest binding, voice therapy or shoe lifts), following an assessment of gender health needs.

Clinical scenario: Alex

Alex (they) began pubertal suppression at Tanner Stage 2 (18 months ago) and is now 14 years old. Alex does not want to go through endogenous (testosterone-based) puberty, in particular development of a deep voice, growing of facial and/or body hair, or enlargement of genitals and/or testicles. They also prefer not to have some changes that would result from exogenous (oestrogen-based) hormone therapy, particularly breast or chest tissue development. Alex is looking for softer skin and no change to their current voice. Alex says, “I don’t want to look like a man or a woman, I want a body shape that is in-between”. They are asking to continue GnRHa monotherapy or to try oestradiol therapy with SERMs to block the unwanted effects of oestrogen (such as breast or chest tissue development) but are open to other ideas (Box 1).

In care planning with Alex, it will be important to further explore which gender-embodiment goals are most important to them and which therapeutic options would be likely to result in the greatest benefit. A care plan that involves a short-term continuation (6 additional months) of GnRHa monotherapy, with vitamin D and calcium supplementation if Alex does not meet daily requirements132,133,134, and weight-bearing activity (to maintain bone density) might be helpful in providing time to make decisions about which future options will best address Alex’s goals. At present, the analysis would not support the use of SERMs within the scenario described (Box 1).

Clinical scenario: Ari

Ari (they) presents 12 months post menarche, at age 13.5 years, and in Tanner Stage 4. Their main embodiment goals are to stop monthly bleeding, stop breast or chest tissue development, and to grow taller. Ari wants lower levels of oestrogen and testosterone than would be typical with either endogenous hormones or standard testosterone therapy. They are interested in testosterone therapy to have a slightly deeper voice and some facial and/or body hair growth, and are okay with developing genital growth but are concerned about scalp hair loss.

In working with Ari, it will be important to distinguish the embodiment goals that are achievable from those that are not (Box 2). Height change is probably not possible; owing to Ari’s age and being 12 months post menarche, they have probably attained more than 95% of their adult height. It is unclear if further breast or chest tissue development can be stopped at Tanner Stage 4 (refs. 135,136). Goals that are probably not achievable should be discussed with respect and care. Achievable goals should be the focus of medical therapy care planning (that is, stopping monthly bleeding, voice deepening, facial and/or body hair growth, and addressing possible hair loss).

Clinical scenario: Sam

Sam (no pronouns) is 15 years old and at Tanner Stage 4. Sam’s main goal is to block endogenous testosterone and its associated physiological and emotional effects. Sam is interested in developing some breast or chest tissue and would like to keep fertility options open. Sam’s current testicular volume is 12 mL bilaterally (a testicular volume of 12 mL or higher is used as a proxy measure of probable spermatogenesis). GnRHa is recommended to block the effects of testosterone, but Sam is unable to access this option due to a lack of insurance coverage.

Injectable medroxyprogesterone could block testosterone in a more cost-effective manner than GnRHa, but it will not address all embodiment goals (that is, medroxyprogesterone will not cause breast or chest development and will inhibit sperm production) (Box 3). Another option is bicalutamide, and preliminary research shows promise for bicalutamide theoretically addressing all of Sam’s embodiment goals, albeit at a higher cost and potentially greater overall risk of side effects than medroxyprogesterone. The third option is cyproterone acetate, which has variable costs based on the country where it is prescribed but is less expensive than GnRHa. The advantages of cyproterone acetate are the effective suppression of testosterone levels, the potential for chest/breast growth and a low likelihood of substantial side effects. Drawbacks of all three of these options include unknown effects on sperm production or expectation of inhibited sperm production during treatment, and the option of sperm banking should be discussed with Sam. Exploring the benefits, risks and costs of each therapy with Sam (and Sam’s parents and/or guardians) will be important in deciding whether medroxyprogesterone, bicalutamide or cyproterone acetate is an appropriate option for Sam as all options could be ethically defensible. However, cyproterone acetate is most likely to provide the best balance of safety and effectiveness in meeting Sam’s gender-embodiment goals (Box 3).

Conclusion

Standard therapies to address gender-embodiment goals of TNB youth (such as GnRHa, 17β-oestradiol or testosterone) are grounded in theoretical, clinical and research evidence. Novel off-label medical therapies have been proposed to address gender-embodiment goals not attainable via standard options. We have reviewed the available evidence and potential benefits of novel therapies (such as 5αRIs and NSAAs) and applied the ethical principles of evidence, benefit, safety, respect, care, communication, transparency, equity and innovation in analysing three theoretical clinical scenarios. We conclude that standard medical therapies are ethically justified and that proposed novel therapies can be ethically acceptable when carefully analysed in the context of an individual’s comprehensive care plan and with respect to the available theoretical, clinical and research evidence, potential benefits, and potential risks. Additional research on proposed novel therapies utilizing ethically appropriate methodologies (for example, case reports and prospective cohort studies evaluating effectiveness in addressing gender-embodiment goals) will be beneficial in supporting ethical clinical decision-making in the care of TNB youth. When novel approaches are developed and implemented, sharing these innovations is critical to advancing gender healthcare.

References

Coleman, E. et al. Standards of care for the health of transgender and gender diverse people (version 8). Int. J. Transgender Health 23, S1–S259 (2022).

Chen, D. et al. Psychosocial functioning in transgender youth after 2 years of hormones. N. Engl. J. Med. 388, 240–250 (2023).

de Vries, A. L. C. et al. Young adult psychological outcome after puberty suppression and gender reassignment. Pediatrics 134, 696–704 (2014).

Tordoff, D. M. et al. Mental health outcomes in transgender and nonbinary youths receiving gender-affirming care. JAMA Netw. Open 5, e220978 (2022).

Turban, J. L., King, D., Kobe, J., Reisner, S. L. & Keuroghlian, A. S. Access to gender-affirming hormones during adolescence and mental health outcomes among transgender adults. PLoS One 17, e0261039 (2022).

Tan, K. K. H., Byrne, J. L., Treharne, G. J. & Veale, J. F. Unmet need for gender-affirming care as a social determinant of mental health inequities for transgender youth in Aotearoa/New Zealand. J. Public Health 45, e225–e233 (2023).

van der Miesen, A. I. R., Steensma, T. D., de Vries, A. L. C., Bos, H. & Popma, A. Psychological functioning in transgender adolescents before and after gender-affirmative care compared with cisgender general population peers. J. Adolesc. Health 66, 699–704 (2020).

Fisher, A. D. et al. Back to the future: is GnRHa treatment in transgender and gender diverse adolescents only an extended evaluation phase? J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 109, 1565–1579 (2024).

Hastings, J., Bobb, C., Wolfe, M., Amaro Jimenez, Z. & Amand, C. S. Medical care for nonbinary youth: individualized gender care beyond a binary framework. Pediatr. Ann. 50, e384–e390 (2021).

Handler, T. et al. Trends in referrals to a pediatric transgender clinic. Pediatrics 144, e20191368 (2019).

Khatchadourian, K., Amed, S. & Metzger, D. L. Clinical management of youth with gender dysphoria in Vancouver. J. Pediatr. 164, 906–911 (2014).

Hembree, W. C. et al. Endocrine treatment of gender-dysphoric/gender-incongruent persons: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 102, 3869–3903 (2017).

Telfer, M. M., Tollit, M. A., Pace, C. C. & Pang, K. C. Australian standards of care and treatment guidelines for trans and gender diverse children and adolescents version 1.3. The Royal Children's Hospital Melbourne https://www.rch.org.au/uploadedFiles/Main/Content/adolescent-medicine/australian-standards-of-care-and-treatment-guidelines-for-trans-and-gender-diverse-children-and-adolescents.pdf (2020).

Health Policy Project, Asia Pacific Transgender Network & United Nations Development Programme. Blueprint for the provision of comprehensive care for trans people and trans communities in Asia and the Pacific. United Nations Development Programme https://www.undp.org/asia-pacific/publications/blueprint-provision-comprehensive-care-trans-people-and-trans-communities-asia-and-pacific (2015).

Pan American Health Organization, John Snow, Inc. & World Professional Association for Transgender Health. Blueprint for the provision of comprehensive care for trans persons and their communities in the Caribbean and other anglophone countries. Pan American Health Organization https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/31360 (2014).

Danish Health Authority. Guide on healthcare related to gender identity. Danish Health Authority https://www.sst.dk/-/media/English/Publications/2018/Guide-on-healthcare-related-to-gender-identity.ashx (2018).

Oliphant, J. et al. Guidelines for gender affirming healthcare for gender diverse and transgender children, young people and adults in Aotearoa, New Zealand. N. Z. Med. J. 131, 86–96 (2018).

Tomson, A. et al. Southern African HIV Clinicians Society gender-affirming healthcare guideline for South Africa. S. Afr. J. HIV Med. 22, 27 (2021).

T’Sjoen, G. et al. European Society for Sexual Medicine position statement “Assessment and hormonal management in adolescent and adult trans people, with attention for sexual function and satisfaction”. J. Sex. Med. 17, 570–584 (2020).

Hidalgo, M. A. et al. The gender affirmative model: what we know and what we aim to learn. Hum. Dev. 56, 285–290 (2013).

Cohen-Kettenis, P. T. & van Goozen, S. H. M. Pubertal delay as an aid in diagnosis and treatment of a transsexual adolescent. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 7, 246–248 (1998).

Schagen, S. E. E., Cohen-Kettenis, P. T., Delemarre-van de Waal, H. A. & Hannema, S. E. Efficacy and safety of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist treatment to suppress puberty in gender dysphoric adolescents. J. Sex. Med. 13, 1125–1132 (2016).

Klaver, M. et al. Hormonal treatment and cardiovascular risk profile in transgender adolescents. Pediatrics 145, e20190741 (2020).

Perl, L., Segev-Becker, A., Israeli, G., Elkon-Tamir, E. & Oren, A. Blood pressure dynamics after pubertal suppression with gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs followed by testosterone treatment in transgender male adolescents: a pilot study. LGBT Health 7, 340–344 (2020).

Valentine, A. et al. Multicenter analysis of cardiometabolic-related diagnoses in transgender and gender-diverse youth: a PEDSnet study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 107, e4004–e4014 (2022).

Waldner, R. C., Doulla, M., Atallah, J., Rathwell, S. & Grimbly, C. Leuprolide acetate and QTC interval in gender-diverse youth. Transgender Health 8, 84–88 (2023).

Nokoff, N. J. et al. Body composition and markers of cardiometabolic health in transgender youth on gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists. Transgender Health 6, 111–119 (2021).

Carmichael, P. et al. Short-term outcomes of pubertal suppression in a selected cohort of 12 to 15 year old young people with persistent gender dysphoria in the UK. PLoS One 16, e0243894 (2021).

de Vries, A. L. C., Steensma, T. D., Doreleijers, T. A. H. & Cohen-Kettenis, P. T. Puberty suppression in adolescents with gender identity disorder: a prospective follow-up study. J. Sex. Med. 8, 2276–2283 (2011).

Nieder, T. O. et al. Individual treatment progress predicts satisfaction with transition-related care for youth with gender dysphoria: a prospective clinical cohort study. J. Sex. Med. 18, 632–645 (2021).

Lavender, R. et al. Impact of hormone treatment on psychosocial functioning in gender-diverse young people. LGBT Health 10, 382–390 (2023).

Turban, J. L., King, D., Carswell, J. M. & Keuroghlian, A. S. Pubertal suppression for transgender youth and risk of suicidal ideation. Pediatrics 145, e20191725 (2020).

Rosenthal, S. M. Challenges in the care of transgender and gender-diverse youth: an endocrinologist’s view. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 17, 581–591 (2021).

Chen, D. et al. Consensus parameter: research methodologies to evaluate neurodevelopmental effects of pubertal suppression in transgender youth. Transgender Health 5, 246–257 (2020).

Hannema, S. E., Schagen, S. E. E., Cohen-Kettenis, P. T. & Delemarre-van de Waal, H. A. Efficacy and safety of pubertal induction using 17β-estradiol in transgirls. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 102, 2356–2363 (2017).

Mahfouda, S. et al. Gender-affirming hormones and surgery in transgender children and adolescents. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 7, 484–498 (2019).

Vance, S. R., Ehrensaft, D. & Rosenthal, S. M. Psychological and medical care of gender nonconforming youth. Pediatrics 134, 1184–1192 (2014).

Jarin, J. et al. Cross-sex hormones and metabolic parameters in adolescents with gender dysphoria. Pediatrics 139, e20163173 (2017).

Perl, L. et al. Blood pressure dynamics after pubertal suppression with gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs followed by estradiol treatment in transgender female adolescents: a pilot study. J. Ped. Endocrinol. Metab. 34, 741–745 (2021).

Stoffers, I. E., De Vries, M. C. & Hannema, S. E. Physical changes, laboratory parameters, and bone mineral density during testosterone treatment in adolescents with gender dysphoria. J. Sex. Med. 16, 1459–1468 (2019).

Millington, K. et al. Laboratory changes during gender-affirming hormone therapy in transgender adolescents. Pediatrics 153, e2023064380 (2024).

Tack, L. J. W. et al. Consecutive lynestrenol and cross-sex hormone treatment in biological female adolescents with gender dysphoria: a retrospective analysis. Biol. Dec. Differ. 7, 14 (2016).

Millington, K. et al. The effect of gender-affirming hormone treatment on serum creatinine in transgender and gender-diverse youth: implications for estimating GFR. Ped. Nephrol. 37, 2141–2150 (2022).

Olson-Kennedy, J. et al. Emotional health of transgender youth 24 months after initiating gender-affirming hormone therapy. J. Adolesc. Health https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2024.11.014 (2025).

Grannis, C. et al. Testosterone treatment, internalizing symptoms, and body image dissatisfaction in transgender boys. Psychoneuroendocrinology 132, 105358 (2021).

O’Connell, M. A., Nguyen, T. P., Ahler, A., Skinner, S. R. & Pang, K. C. Approach to the patient: pharmacological management of trans and gender-diverse adolescents. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 107, 241–257 (2022).

Burinkul, S., Panyakhamlerd, K., Suwan, A., Tuntiviriyapun, P. & Wainipitapong, S. Anti-androgenic effects comparison between cyproterone acetate and spironolactone in transgender women: a randomized controlled trial. J. Sex. Med. 18, 1299–1307 (2021).

Schwartz, B. I., Bear, B. & Kazak, A. E. Menstrual management choices in transgender and gender diverse adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 72, 207–213 (2023).

Lynch, M. M., Khandheria, M. M. & Meyer, W. J. III Retrospective study of the management of childhood and adolescent gender identity disorder using medroxyprogesterone acetate. Int. J. Transgend. 16, 201–208 (2015).

Foglia, M. B. & Fredriksen-Goldsen, K. I. Health disparities among LGBT older adults and the role of nonconscious bias. Hastings Cen. Rep. 44, S40–S44 (2014).

Clark, D. B. A. Narratives of regret: resisting cisnormative and bionormative biases in fertility and family creation counseling for transgender youth. IJFAB 14, 157–179 (2021).

Lepore, C., Alstott, A. & McNamara, M. Scientific misinformation is criminalizing the standard of care for transgender youth. JAMA Pediatr. 176, 965–966 (2022).

Clark, D. B. A., Veale, J. F., Greyson, D. & Saewyc, E. Primary care access and foregone care: a survey of transgender adolescents and young adults. Fam. Pract. 35, 302–306 (2018).

Clark, D. B. A., Veale, J. F., Townsend, M., Frohard-Dourlent, H. & Saewyc, E. M. Non-binary youth: access to gender-affirming primary health care. Int. J. Transgend. 19, 158–169 (2018).

Paceley, M. S. et al. “I have nowhere to go”: a multiple-case study of transgender and gender diverse youth, their families, and healthcare experiences. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18, 9219 (2021).

Gridley, S. J. et al. Youth and caregiver perspectives on barriers to gender-affirming health care for transgender youth. J. Adolesc. Health 59, 254–261 (2016).

Kearns, S., Kroll, T., O’Shea, D. & Neff, K. Experiences of transgender and non-binary youth accessing gender-affirming care: a systematic review and meta-ethnography. PLoS One 16, e0257194 (2021).

Wall, C. S. J., Patev, A. J. & Benotsch, E. G. Trans broken arm syndrome: a mixed-methods exploration of gender-related medical misattribution and invasive questioning. Soc. Sci. Med. 320, 115748 (2023).

McGeough, B. L. et al. Transgender and gender diverse youth’s perspectives of affirming healthcare: findings from a community-based study in Kansas. SAGE Open 13, https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440231184843 (2023).

Goldenberg, T. et al. Stigma, gender affirmation, and primary healthcare use among black transgender youth. J. Adolesc. Health 65, 483–490 (2019).

Chong, L. S. H. et al. Experiences and perspectives of transgender youths in accessing health care: a systematic review. JAMA Pediatr. 175, 1159–1173 (2021).

Pampati, S. et al. “We deserve care and we deserve competent care”: qualitative perspectives on health care from transgender youth in the southeast United States. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 56, 54–59 (2021).

Hendricks, M. L. & Testa, R. J. A conceptual framework for clinical work with transgender and gender nonconforming clients: an adaptation of the minority stress model. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 43, 460–467 (2012).

Reisner, S. L., Greytak, E. A., Parsons, J. T. & Ybarra, M. L. Gender minority social stress in adolescence: disparities in adolescent bullying and substance use by gender identity. J. Sex. Res. 52, 243–256 (2015).

Veale, J. F., Peter, T., Travers, R. & Saewyc, E. M. Enacted stigma, mental health, and protective factors among transgender youth in Canada. Transgender Health 2, 207–216 (2017).

Pang, K. C., Hoq, M. & Steensma, T. D. Negative media coverage as a barrier to accessing care for transgender children and adolescents. JAMA Netw. Open 5, e2138623 (2022).

Hughes, L. D. et al. Adolescent providers’ experiences of harassment related to delivering gender-affirming care. J. Adolesc. Health 73, 672–678 (2023).

Hughes, L. D., Kidd, K. M., Gamarel, K. E., Operario, D. & Dowshen, N. These laws will be devastating”: provider perspectives on legislation banning gender-affirming care for transgender adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 69, 976–982 (2021).

Taylor, J. et al. Masculinising and feminising hormone interventions for adolescents experiencing gender dysphoria or incongruence: a systematic review. Arch. Dis. Child. 109, s48–s56 (2024).

Ashley, F., Tordoff, D. M., Olson-Kennedy, J. & Restar, A. J. Randomized-controlled trials are methodologically inappropriate in adolescent transgender healthcare. Int. J. Transgender Health 25, 407–418 (2024).

McNamara, M. et al. An Evidence-Based Critique of “the Cass review” on Gender-Affirming Care for Adolescent Gender Dysphoria https://law.yale.edu/sites/default/files/documents/integrity-project_cass-response.pdf (2024).

van der Zanden, T. M. et al. Off-label, but on-evidence? A review of the level of evidence for pediatric pharmacotherapy. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 112, 1243–1253 (2022).

McNamara, M. et al. Scientific misinformation and gender affirming care: tools for providers on the front lines. J. Adolesc. Health 71, 251–253 (2022).

Alexander, J. & Smith, J. Disinformation: a taxonomy. IEEE Secur. Priv. Mag. 9, 58–63 (2011).

Weithorn, L. A. & Campbell, S. B. The competency of children and adolescents to make informed treatment decisions. Child. Dev. 53, 1589–1598 (1982).

Goodlander, E. C. & Berg, J. W. in Clinical Ethics in Pediatrics: A Case-Based Textbook (eds Diekema, D. S., Mercurio, M. R. & Adam, M. B.) 7–13 (Cambridge University Press, 2011).

Michaud, P.-A., Blum, R. W., Benaroyo, L., Zermatten, J. & Baltag, V. Assessing an adolescent’s capacity for autonomous decision-making in clinical care. J. Adolesc. Health 57, 361–366 (2015).

Canadian Paediatric Society. Treatment decisions regarding infants, children and adolescents. Paediatr. Child. Health 9, 99–103 (2004).

Clark, D. B. A. & Virani, A. “This wasn’t a split-second decision”: an empirical ethical analysis of transgender youth capacity, rights, and authority to consent to hormone therapy. J. Bioeth. Inq. 18, 151–164 (2021).

Lev, A. I. Transgender Emergence: Therapeutic Guidelines for Working with Gender-Variant People and Their Families (Routledge, 2004).

Kelly, C. J. & Young, A. J. Promoting innovation in healthcare. Future Healthc. J. 4, 121–125 (2017).

Van Norman, G. A. Off-label use vs off-label marketing of drugs. JACC Basic Transl. Sci. 8, 224–233 (2023).

Day, R. Off-label prescribing. Aust. Prescriber 36, 182–183 (2013).

Council of Australian Therapeutic Advisory Groups. Rethinking medicines decision-making in Australian hospitals: guiding principles for the quality use of off-label medicines. Council of Australian Therapeutic Advisory Groups https://catag.org.au/resource/rethinking-medicines-decision-making-in-australian-hospitals/ (2015).

Jones, A. Redefining gender. National Geographic http://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/2017/01/explore-gender-glossary-terminology/ (2016).

Dresser, R. & Frader, J. Off-label prescribing: a call for heightened professional and government oversight. J. Law Med. Ethics 37, 476–396 (2009).

American Medical Association. Report 4 of the Council on Science and Public Health: hormone therapies: off-label uses and unapproved formulations. American Medical Association https://www.ama-assn.org/sites/ama-assn.org/files/corp/media-browser/2016-interim-csaph-report-4.pdf (2016).

Braüner, J. V., Johansen, L. M., Roesbjerg, T. & Pagsberg, A. K. Off-label prescription of psychopharmacological drugs in child and adolescent psychiatry. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 36, 500–507 (2016).

Cuzzolin, L., Zaccaron, A. & Fanos, V. Unlicensed and off-label uses of drugs in paediatrics: a review of the literature. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 17, 125–131 (2003).

Carel, J., Lahlou, N., Roger, M. & Chaussain, J. L. Precocious puberty and statural growth. Hum. Reprod. Update 10, 135–147 (2004).

Yu, R., Yang, S. & Hwang, I. T. Psychological effects of gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist treatment in girls with central precocious puberty. J. Ped. Endocrinol. Metab. 32, 1071–1075 (2019).

Bangalore Krishna, K. et al. Use of gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs in children: update by an international consortium. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 91, 357–372 (2019).

Delemarre-van de Waal, H. A. & Cohen-Kettenis, P. T. Clinical management of gender identity disorder in adolescents: a protocol on psychological and paediatric endocrinology aspects. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 155, S131–S137 (2006).

Carswell, J. M., Lopez, X. & Rosenthal, S. M. The evolution of adolescent gender-affirming care: an historical perspective. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 95, 649–656 (2022).

Olson-Kennedy, J. et al. Impact of early medical treatment for transgender youth: protocol for the longitudinal, observational trans youth care study. JMIR Res. Protoc. 8, e14434 (2019).

Cocchetti, C., Ristori, J., Romani, A., Maggi, M. & Fisher, A. D. Hormonal treatment strategies tailored to non-binary transgender individuals. J. Clin. Med. 9, 1609 (2020).

Gray, S. G. & McGuire, T. M. Navigating off-label and unlicensed medicines use in obstetric and paediatric clinical practice. J. Pharm. Pract. 49, 389–395 (2019).

Mirkin, S. & Pickar, J. H. Selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs): a review of clinical data. Maturitas 80, 52–57 (2015).

Maximov, P., Lee, T. & Jordan, V. The discovery and development of selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) for clinical practice. Curr. Clin. Pharmacol. 8, 135–155 (2013).

Lapid, O., van Wingerden, J. J. & Perlemuter, L. Tamoxifen therapy for the management of pubertal gynecomastia: a systematic review. J. Ped. Endocrinol. Metab. 26, 803–807 (2013).

Xu, J. Y. et al. Selective estrogen receptor modulators: a potential option for non-binary gender-affirming hormonal care? Front. Endocrinol. 12, 701364 (2021).

Sumino, H. et al. Effects of raloxifene and hormone replacement therapy on forearm skin elasticity in postmenopausal women. Maturitas 62, 53–57 (2009).

Francucci, C. M. et al. Effects of raloxifene on body fat distribution and lipid profile in healthy post-menopausal women. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 28, 623–631 (2005).

Adomaityte, J., Farooq, M. & Qayyum, R. Effect of raloxifene therapy on venous thromboembolism in postmenopausal women: a meta-analysis. J. Thromb. Haemost. 99, 338–342 (2008).

Sun, L.-M., Chen, H.-J., Liang, J.-A., Li, T.-C. & Kao, C.-H. Association of tamoxifen use and increased diabetes among Asian women diagnosed with breast cancer. Br. J. Cancer 111, 1836–1842 (2014).

Xu, B., Lovre, D. & Mauvais-Jarvis, F. Effect of selective estrogen receptor modulators on metabolic homeostasis. Biochimie 124, 92–97 (2016).

Tsourdi, E. et al. The effect of selective estrogen receptor modulator administration on the hypothalamic-pituitary-testicular axis in men with idiopathic oligozoospermia. Fertil. Steril. 91, 1427–1430 (2009).

Azzouni, F., Godoy, A., Li, Y. & Mohler, J. The 5 alpha-reductase isozyme family: a review of basic biology and their role in human diseases. Adv. Urol. 2012, 530121 (2012).

Chislett, B. et al. 5-Alpha reductase inhibitors use in prostatic disease and beyond. Transl. Androl. Urol. 12, 487–496 (2023).

Irwig, M. S. Is there a role for 5α-reductase inhibitors in transgender individuals? Andrology 9, 1729–1731 (2021).

Nguyen, D.-D. et al. Investigation of suicidality and psychological adverse events in patients treated with finasteride. JAMA Dermatol. 157, 35–42 (2021).

Miller, W. R. Aromatase inhibitors: mechanism of action and role in the treatment of breast cancer. Semin. Oncol. 30, 3–11 (2003).

Shulman, D. I., Francis, G. L., Palmert, M. R. & Eugster, E. A.; Lawson Wilkins Pediatric Endocrine Society Drug and Therapeutics Committee.Use of aromatase inhibitors in children and adolescents with disorders of growth and adolescent development. Pediatrics 121, e975–e983 (2008).

Carswell, J. M. & Roberts, S. A. Induction and maintenance of amenorrhea in transmasculine and nonbinary adolescents. Transgender Health 2, 195 (2017).

Rose, L. I., Underwood, R., Newmark, S. R., Kisch, E. S. & Williams, G. H. Pathophysiology of spironolactone-induced gynecomastia. Ann. Intern. Med. 87, 398–403 (1977).

Kolvenbag, G. J. C. M. & Furr, B. J. A. in Hormone Therapy in Breast and Prostate Cancer (eds Jordan, V. C. & Furr, B. J. A.) 347–368 (Humana Press, 2002).

Azarchi, S. et al. Androgens in women: hormone-modulating therapies for skin disease. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 80, 1509–1521 (2019).

Lenz, A. M. et al. Bicalutamide and third-generation aromatase inhibitors in testotoxicosis. Pediatrics 126, e728–e733 (2010).

Neyman, A., Fuqua, J. S. & Eugster, E. A. Bicalutamide as an androgen blocker with secondary effect of promoting feminization in male-to-female transgender adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 64, 544–546 (2019).

Randolph, J. F. J. Gender-affirming hormone therapy for transgender females. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 61, 705 (2018).

Wilde, B. et al. Bicalutamide-induced hepatotoxicity in a transgender male-to-female adolescent. J. Adolesc. Health 74, 202–204 (2024).

Masago, T., Watanabe, T., Nemoto, R. & Motoda, K. Interstitial pneumonitis induced by bicalutamide given for prostate cancer. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 16, 763–765 (2011).

Fitzgerald, A. S. & O’Malley, P. G. Staying on track when prescribing off-label. Am. Fam. Physician 89, 4–5 (2014).

Jones, B. et al. Off-label use of drugs in children. Pediatrics 133, 563–567 (2014).

Lenk, C. & Duttge, G. Ethical and legal framework and regulation for off-label use: European perspective. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 10, 537–546 (2014).

Furey, K. & Wilkins, K. Prescribing “off-label”: what should a physician disclose? AMA J. Ethics 18, 587–593 (2016).

Gazarian, M. et al. Off-label use of medicines: consensus recommendations for evaluating appropriateness. Med. J. Aust. 185, 544–548 (2006).

Bright, J. L. Positive outcomes through the appropriate use of off-label prescribing. Arch. Int. Med. 166, 2554–2555 (2006).

Wilkes, M. & Johns, M. Informed consent and shared decision-making: a requirement to disclose to patients off-label prescriptions. PLoS Med. 5, e223 (2008).

Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. The right to health: fact sheet no. 31. OHCHR & World Health Organization http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Publications/Factsheet31.pdf (2008).

United Nations. Convention on the rights of the child. United Nations http://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/crc.aspx (1989).

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee to Review Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin D and Calcium. Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D (National Academies Press, 2011).

Munns, C. F. et al. Global consensus recommendations on prevention and management of nutritional rickets. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 101, 394–415 (2016).

Navabi, B., Tang, K., Khatchadourian, K. & Lawson, M. L. Pubertal suppression, bone mass, and body composition in youth with gender dysphoria. Pediatrics 148, e2020039339 (2021).

García, C. J. et al. Breast US in children and adolescents. RadioGraphics 20, 1605–1612 (2000).

van de Grift, T. C. et al. Timing of puberty suppression and surgical options for transgender youth. Pediatrics 146, e20193653 (2020).

Lee, J. W. et al. Significant adverse reactions to long-acting gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists for the treatment of central precocious puberty and early onset puberty. Ann. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 19, 135–140 (2014).

Omar, A. A., Nyaga, G. & Mungai, L. N. W. Pseudotumor cerebri in patient on leuprolide acetate for central precocious puberty. Int. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. 2020, 22 (2020).

Millward, C. P. et al. Development and growth of intracranial meningiomas in transgender women taking cyproterone acetate as gender-affirming progestogen therapy: a systematic review. Transgender Health 7, 473–483 (2022).

Cromer, B. A. et al. Bone mineral density in adolescent females using injectable or oral contraceptives: a 24-month prospective study. Fertil. Sterill 90, 2060–2067 (2008).

DiVasta, A. D., Laufer, M. R. & Gordon, C. M. Bone density in adolescents treated with a GNRH agonist and add-back therapy for endometriosis. J. Pediatr. Adololesc. Gynecol. 20, 293–297 (2007).

Zuffo, G., Ricardo, K., Comnisky, H. & Czepula, A. Most prevalent side effects of aromatase inhibitors in the treatment of hormone-positive breast cancer: a scoping review. Mastology 33, e20230033 (2023).

Geffner, M. E. Aromatase inhibitors to augment height: continued caution and study required. J. Clin. Res. Pediatr. Endocrinol. 1, 256–261 (2009).

Korani, M. Aromatase inhibitors in male: a literature review. Med. Clinica Practica 6, 100356 (2023).

Morgante, E. et al. Effects of long-term treatment with the anti-androgen bicalutamide on human testis: an ultrastructural and morphometric study. Histopathology 38, 195–201 (2001).

Vañó-Galván, S. et al. Safety of low-dose oral minoxidil for hair loss: a multicenter study of 1404 patients. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 84, 1644–1651 (2021).

Cea-Soriano, L., Blenk, T., Wallander, M.-A. & Rodríguez, L. A. G. Hormonal therapies and meningioma: is there a link? Cancer Epidemiol. 36, 198–205 (2012).

Moltz, L., Römmler, A., Post, K., Schwartz, U. & Hammerstein, J. Medium dose cyproterone acetate (CPA): effects on hormone secretion and on spermatogenesis in men. Contraception 21, 393–413 (1980).

de Nie, I. et al. Successful restoration of spermatogenesis following gender-affirming hormone therapy in transgender women. Cell Rep. Med. 4, 100858 (2023).

Acknowledgements

D.B.A.C. (they) and D.L.M. (he) live and work within the traditional, ancestral and unceded territories of the xʷməθkwəýəm (Musqueam), Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Úxwumixw (Squamish) and səlili̓lw̓ətaʔɬ (Tsleil-Waututh) Nations. K.C.P. (he) lives and works on the unceded lands of the Wurrundjeri people of the Kulin nation and wishes to acknowledge funding support from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (GNT#2006529 and # 2027186) and the Hugh DT Williamson Foundation. C.S.A. (he/they) lives and works on the traditional lands of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy. K.K. (she) lives and works on unceded Anishinaabe Algonquin territory.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors contributed equally to all aspects of the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

K.K. served on advisory boards or as a consultant for Tolmar.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Reviews Endocrinology thanks Annelou De Vries and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Clark, D.B.A., Metzger, D.L., Pang, K.C. et al. Individualized and innovative gender healthcare for transgender and nonbinary youth. Nat Rev Endocrinol 21, 441–452 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41574-025-01113-z

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41574-025-01113-z