Abstract

Ageing has profound effects on the human brain across the lifespan. Cognitive testing and brain imaging are currently used to monitor healthy and pathological brain ageing. However, peripheral markers of cognitive function, cognitive ageing and neurological disease could provide a valuable, minimally invasive approach to tracking these processes longitudinally. In this Review, we introduce the concept of DNA methylation-based biomarkers and present current evidence of their potential to address the challenge of monitoring brain ageing and stratifying the risk of neurological disease. We focus on epigenetic clocks, which can be applied across multiple tissues and organs to estimate biological ageing, as well as on blood-based epigenetic scores (EpiScores) that can directly track brain-based phenotypes, such as cognitive function, and risk factors for neurological diseases, such as lifestyle behaviours and proteomic markers of inflammation. We discuss the associations between these epigenetic biomarkers and multiple measures of cognitive health, including cognitive test data, brain MRI measures and dementia.

Key points

-

Peripheral markers of neurological function and disease could provide a valuable, minimally invasive approach to aid risk prediction.

-

DNA methylation, an epigenetic modification that varies by tissue or cell type of origin, is an increasingly popular candidate for biomarker development.

-

Methylation patterns from blood, brain and other tissues can be used to build biomarkers for chronological ageing (termed first-generation epigenetic clocks) and other complex traits (for example, cognitive function, mortality or protein levels).

-

Second-generation and third-generation epigenetic clocks, which were built to predict the healthspan, lifespan and rate of biological ageing, associate more strongly with health outcomes than do first-generation clocks but currently neither show robust associations with dementia.

-

Methylation biomarkers for other complex traits, including inflammatory protein levels and cognitive function, show promise for tracking risk factors for neurodegeneration.

-

Methylation biomarkers might offer an effective way to track brain health across the life course.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Age and ageing are the strongest risk factors for cognitive decline and neurodegenerative disease. However, individuals of the same chronological age can exhibit different rates of biological ageing, which might manifest as cognitive decline or the diagnosis of a neurodegenerative disease. Quantifying chronological age is trivial, but objectively assessing rates of ageing or determining the biological age of an individual is more challenging.

Over the past decade, we have seen an upsurge of interest in biomarkers of ageing based on DNA methylation1,2 (DNAm), an epigenetic modification in which methyl groups are added to the DNA sequence, typically at cytosine–guanine (CpG) dinucleotides. These chemical modifications are dynamic and tissue-specific. By compiling information from thousands of DNA molecules per sample, we can determine the percentage of methylated cytosines at each CpG site (Fig. 1). DNAm patterns in blood are associated with chronological age across diverse mammalian species3,4 as well as with measures of brain health in humans5,6.

The graph uses hypothetical data to illustrate how the percentage of methylated cytosines at a single cytosine–guanine (CpG) site across cells can correlate with chronological age. The data point inside the dashed circle shows an individual aged ~20 years with ~75% methylation at a specific CpG site — a methylation level that deviates considerably from other individuals at that age. Such deviations can be considered as accelerated or decelerated biological ageing, depending on the direction of deviation. In this case, the methylation level of the individual in their twenties looks more like that of an individual in their seventies; therefore, we would describe this scenario as accelerated biological ageing.

In this Review, we provide a general introduction to the concepts of accelerated epigenetic ageing and epigenetic biomarkers, along with the statistical methods that are commonly used to construct epigenetic clocks. We go on to discuss epigenetic clocks that were trained to predict chronological age — so-called ‘first-generation’ clocks — in adult blood and multi-tissue samples, post-mortem brain tissue samples and neonatal multi-tissue samples. After outlining the general limitations shared by all first-generation clocks, we highlight some key second-generation and third-generation clocks that were trained to predict ageing-related outcomes and rates of change in biological ageing rather than chronological ageing. We then present an overview of the associations between first-generation, second-generation and third-generation clocks and endophenotypes of brain ageing, cognitive function and neurological disease. This discussion is complemented by a summary of epigenetic predictors for lifestyle factors, protein levels and cognitive function, all of which have been highlighted as potential biomarkers of neurological disease. We conclude by highlighting the general strengths and limitations of epigenetic biomarkers and proposing future directions and opportunities for the field.

Epigenetic clocks

Association studies using methylation proportions at individual CpG sites have yielded important insights into individual differences in biological ageing1,2. One of the best-replicated ageing-associated CpGs is cg16867657, which maps to ELOVL2, a gene linked to the elongation of fatty acids. Methylation at this site correlates closely with age (Pearson correlation >0.9) in cohorts that considered the adult lifespan7,8. Given this association, a logical next step is to focus on deviations from a line of best fit to identify individuals above and below the expected value for their age, which could be crudely interpreted as accelerated or decelerated ageing, respectively.

In addition to single-CpG–age correlations, signatures that combine information from multiple age-related CpG sites can be generated1,2 using various statistical approaches, with elastic net penalized regression (Fig. 2) being among the most common. The resulting predictions are often labelled ‘epigenetic age’, and the deviation between this value and chronological age is termed ‘epigenetic age acceleration’. The weighted CpG formulae that are used to derive epigenetic age can be referred to as ‘epigenetic clocks’. When epigenetic clocks are applied and tested in a cohort, an association between the age acceleration deviation and chronological age might still be present. To remove this possible source of confounding, the raw differences between epigenetic age and chronological age are often replaced with age acceleration residuals derived from a linear regression of epigenetic age on chronological age.

A linear regression with 850,000 predictor variables can result in a large and complex model, which might not replicate when tested in new datasets. Penalized regression approaches, such as elastic net regression, can identify sparse solutions where many of the possible features that are not important for predicting the outcome (certain cytosine–guanine (CpGs) in this case) are assigned regression weights of zero. a, Epigenetic clocks are trained on single or multiple cohorts with large sample sizes reflecting a wide range of ages and diverse backgrounds. b, In this example, the training cohort dataset includes 850,000 CpGs measured across 10,000 individuals; the proportions of DNA molecules methylated at each CpG site for each person are tabulated. c, The resulting epigenetic age predictor relies on the weighted average of methylation across a subset of CpGs, four of which are highlighted here. d, Ideally, external, independent datasets (test datasets) are used to validate and test the performance of the epigenetic clock. If this is not possible, a random subset of the data not used for training (termed a holdout sample) can be used. e, Model performance metrics, such as Pearson correlation or median absolute error, are calculated in the testing cohort.

Building an epigenetic clock

In the context of epigenetic clock development, penalized regression approaches can take all — or a user-specified subset of — CpG sites as potentially predictive features (termed predictor or independent variables). Although whole-methylome sequencing methods can capture all ~30 million CpG sites in the genome, array-based approaches, particularly those developed by Illumina, have been most widely assessed across cohort studies and used for the development of epigenetic clocks. Illumina BeadChip arrays have been developed to profile ~27,000 CpGs (27 K array), ~450,000 CpGs (450 K array) or ~850,000 CpGs (EPICv1 and EPICv2 arrays)9,10,11,12. The vast majority of CpG loci on the smaller arrays are also present on the larger arrays. Recently, the Methylation Screening Array, which profiles ~270,000 CpG sites, was developed with large-scale biobanks as its target application13.

A simple overview of how to generate a first-generation epigenetic clock is presented in Fig. 2. Briefly, one starts with a training dataset, which could be a single cohort or a combination of cohorts. To maximize the chances of a clock being generalizable across different populations or cohorts, the training dataset should ideally contain an equal mix of individuals from diverse backgrounds and cover a wide range of ages. If a less heterogeneous cohort of individuals is used, for example, from a single country or within a narrow age range, the observed differences in methylation patterns might not reflect those from other backgrounds or ages. After building the epigenetic clock, it is best practice to test how well it performs in external datasets, known as test datasets, that were not used to develop the clock. Predictive accuracy is often assessed by multiple metrics, including the Pearson correlation between epigenetic age and chronological age, and the median absolute error or root mean square error of the difference between epigenetic age and chronological age.

First-generation epigenetic clocks

Epigenetic clocks with chronological age as the outcome are commonly referred to as first-generation clocks, whereas those trained on ageing-related outcomes, such as all-cause mortality, are termed second-generation clocks (Fig. 3).

First-generation clocks were constructed using DNA methylation (DNAm) data from blood, specific tissues or multiple tissues and chronological age. Second-generation clocks have used multiple different approaches, including DNAm proxies for various ageing-related biomarkers and phenotypic outcomes, such as mortality, to generate clocks of biological rather than chronological age. Third-generation clocks have focused on tracking the rate of biological ageing.

Some of the earliest first-generation epigenetic clocks were reported in 2011 (refs. 14,15). These clocks comprised a saliva-based predictor trained on 68 individuals and a multi-cell/multi-tissue (dermis, epidermis, cervical smear and blood) predictor trained on 130 samples and tested on saliva, peripheral and umbilical cord blood, and breast organoid datasets. These clocks, both of which used methylation data from the Illumina 27 K array, gave mean absolute errors of around 5 years and 10 years, respectively, in the test sets.

In January 2013, the field saw a step change with the publication of a 71-CpG blood-based clock by Hannum et al.16 trained on 482 individuals. In December of the same year, Horvath reported on a 353-CpG pan-tissue clock17, which was based on accumulated data from ~8,000 samples from over 50 tissues. Both clocks noted test-set Pearson correlations of >0.9 between epigenetic age and chronological age and reported median absolute prediction errors of around 4 years. Among the extensive findings, these papers described differences in epigenetic ageing by sex (higher age estimates for males), applicability of human-trained clocks to primates and a near-zero predicted age for embryonic stem cells. Both clocks have since been applied extensively to human cohort studies. One of the most widely reproduced associations was with all-cause mortality18,19, whereby epigenetic age acceleration was linked to reduced longevity.

Brain-based epigenetic clocks

Although blood-based or saliva-based predictors are optimal from an accessibility standpoint, application of peripheral tissue clocks to brain-specific pathology might limit the biological insights that can be gained20. Clocks based on post-mortem cortical tissue have been examined both in people with neurodegenerative disease20,21,22,23 and in dementia-free populations24 and were found to exhibit stronger associations with clinical markers of neurodegeneration than did multi-tissue or blood-based clocks23,25. Figure 4 presents an overview of the cortical epigenetic clocks developed to date.

The figure shows key events in the development of cortical epigenetic clocks20,21,22,23,31,32,33. Before Shireby et al.20, no DNA methylation (DNAm) age clock had been trained using brain tissue samples to develop a specific cortical clock, although several blood-based and pan-tissue clocks had been tested in post-mortem brain samples.

The first of these clocks was developed by Shireby et al. using elastic net regression20 (Fig. 2). Human post-mortem cortical DNAm data were obtained from individuals aged 1–108 years (n = 1,397), excluding people with Alzheimer disease, to train DNAmClockCortical (347 CpG sites). This clock was subsequently tested in a holdout sample from the same cohort (n = 350) and validated on cortical tissue from an independent cohort (n = 1,221, 41–104 years of age). Less than 5% of the CpGs selected for the clock overlapped with those highlighted in previous blood or multi-tissue DNAm clocks. DNAmClockCortical showed better age predictions for brain tissue than did peripheral tissue-based clocks but was inferior to other multi-tissue or blood-based clocks for predicting age from DNAm in blood20.

Concordance between datasets — for example, having cortical tissue as the basis for both the training dataset and the prediction sample — is an important consideration when developing and testing epigenetic clocks. Moreover, the composition of the tissue — for example, bulk cortical tissue composed of heterogeneous cell types versus distinct cell populations — is highly relevant as neuronal and non-neuronal cell populations change substantially during neurodegenerative disease progression. Bulk DNAm profiling might obscure disease-specific alterations in brain cell types26, particularly in the context of Alzheimer disease, which is characterized by changes in the activation, proliferation and proportions of distinct cell populations27. In support of this idea, an epigenome-wide association study28 (EWAS), which profiled 631 post-mortem samples from the Brains for Dementia Research dataset29, found that most DNAm differences observed in bulk cortical tissue arose from variation in non-neuronal cell types. In another study, older cortical DNAm age, as assessed by DNAmClockCortical, was related to higher glial cell proportions across several white matter regions, including the corpus callosum, frontal lobes and occipital lobes, and specific adjustment for oligodendrocyte proportions affected age acceleration estimates in different brain regions21.

The application of epigenetic clocks to profile brain ageing is in its infancy, particularly in human brain tissue samples. Few brain region-specific or tissue-specific clocks have been developed; for instance, hippocampal ageing clocks have only been created in mouse models to date30. A strong case can be made for developing more accessible predictors of brain ageing from peripheral tissue surrogates, given that DNAm patterns are dynamic, and that clocks are primarily intended to be applied to living individuals. Peripheral biosamples offer a routine way to assess longitudinal DNAm trajectories and explore whether they change in parallel with measures of brain function or disease progression. DNAm age, as estimated by a range of epigenetic clocks trained on blood, has also been calculated in cerebrospinal fluid31 (CSF), although no CSF-based clocks have been developed with CSF DNAm as the training data. Similarly, several studies24,32,33 have applied peripheral blood-based clocks or pan-tissue clocks to post-mortem brain tissue.

In general, the performance of DNAm clocks tends to plateau in older age, leading to discrepancies between predicted and actual age. Several epigenetic clocks show non-linear variations in predictive accuracy with age and systemically underestimate values for individuals over the age of 60 years20. When a range of clocks was examined in cortical tissue20, DNAmClockCortical showed the smallest age-related bias, illustrating the benefits of tissue-specific clocks. Debate is ongoing about whether multi-tissue clocks accurately capture the ageing rate of different tissue types. Some studies suggested that the cerebellum has a slower DNAm ageing rate than other brain regions33,34; however, more recent work indicates that current multi-tissue DNAm clocks significantly underestimate cerebellar epigenetic age, particularly when brain tissues are under-represented in the training data22. In this study, 613 age-associated CpGs were found in cerebellar tissue from 752 individuals. Of these CpGs, only 201 overlapped between the cerebellum and other cortical regions, illustrating the importance of considering tissue-specific methylation changes when developing epigenetic clocks. Other clocks, such as PCBrainAge, which was trained on post-mortem dorsolateral prefrontal cortex samples, have shown associations with molecular hallmarks of neurodegeneration such as neuritic plaques, diffuse plaques and neurofibrillary tangles23. Overall, a clear case exists for tissue-specific clocks to better understand brain ageing but also for more accessible predictors that signal deviations in brain health trajectories. Epigenetic clocks might need to be tailored to specific disease processes, focusing on CpG sites that are highly correlated across brain and other tissues to improve their accuracy.

Gestational epigenetic clocks

Recognizing that DNAm profiles change rapidly during development, bespoke clocks have also been derived for this period of life. These clocks are designed to provide precise estimates of gestational age and might help to identify deviations from typical gestation that could signal adverse health outcomes. There is a strong clinical precedent for accurate predictors of gestational age, as even a 1-week difference can influence neonatal morbidity, mortality and long-term postnatal health35. For example, differential exposure to factors such as preterm birth or perinatal inflammatory disease burden during a key developmental period increases the risk of negative neurodevelopmental and cognitive outcomes36,37,38.

Choice of tissue type is perhaps even more important for building accurate clocks for use during gestation than at other time points owing to the unique shared exposome of pregnancy39. Gestational epigenetic clocks have been derived from umbilical cord blood35,40,41,42, placental tissue43,44 and buccal cells, and they include the Paediatric-Buccal-Epigenetic (PedBE) clock45, which has been linked to poor neurodevelopmental outcomes46, and the Neonatal Epigenetic Estimator of age (NEOage) clock47.

The differing features of these tissues determine their relevance to specific avenues of study. Given the key role of the placenta as a mediator between maternal and fetal systems, placental tissue is highly relevant for examining the maternal–fetal axis, in particular, the epigenome of fetal development, pregnancy complications and maternal lifestyle influence48. In studies focusing on very preterm infants (<32 weeks’ gestational age), buccal cells and saliva are often the preferred samples because they can be collected non-invasively. Buccal cells could offer insights into neurodevelopmental processes owing to a shared origin with CNS cells in the ectoderm during embryonic development49,50. They also yield a higher proportion of epithelial cells and have lower bacterial contamination compared with saliva51.

Limitations and future refinements

All clocks that are trained to predict chronological age have limitations, perhaps the foremost of which is their inability to specifically capture disease risk. Although chronological age is one of the most important risk factors for a multitude of diseases, including late-onset neurodegenerative conditions, deviations in epigenetic age acceleration are not designed to provide disease-specific insights. One study indicated that near-perfect, potentially forensic prediction of chronological age will become feasible as training sample sizes increase52. The same study also showed that clocks built using smaller training samples tended to include CpGs that are variable across white cell types. As differences in white cell proportions also track systemic ill health, this can lead to associations between clocks and all-cause mortality. These issues diminish with larger training samples.

A study published in 2023 showed that the median absolute error for chronological age could be reduced to below 2 years8. The model that was used in this study was trained on 24,674 biosamples from 11 cohorts, and the CpGs were pre-filtered to select those that showed linear or quadratic associations with age. The incorporation of non-linear associations and methodologies is likely to provide further insights given the rapid changes in CpG methylation that are seen during development and the saturation effects that are seen in late life.

Second-generation and third-generation epigenetic clocks

To overcome some of the issues with first-generation clocks trained on chronological age, second-generation clocks are being developed with health-related measures as the outcomes. The most widely used second-generation clocks include GrimAge and PhenoAge.

These clocks have subtle differences in their construction. GrimAge53 used a two-stage approach whereby elastic net regression was initially used to generate DNAm signatures for a host of plasma proteins and smoking pack years. Along with age and sex, these methylation surrogates were then used as potential inputs in a second-stage Cox elastic net regression (similar to the model shown in Figure 2 but with a time-to-event outcome in place of chronological age) where all-cause mortality was the outcome. PhenoAge54 also used a two-stage approach but initially trained a biomarker and risk factor predictor of all-cause mortality using a Cox penalized regression model. Elastic net regression (Fig. 2) was then used to train a DNAm epigenetic clock for the biomarker-based predictor.

Two additional clocks, Dunedin PoAm55 and DunedinPACE56, were built to track the longitudinal rate of change in 18 and 19 biomarkers of ageing, respectively. The former measured the rate of change over three time points between 26 and 38 years of age, whereas the latter considered the rate of change over four time points between 26 and 45 years of age. The researchers then generated a composite trajectory and trained an epigenetic predictor for the rate of change. As they capture the rate of change as opposed to a static measure, such as chronological age or time to all-cause mortality, the Dunedin predictors have been described as third-generation clocks.

Other clocks have been proposed in recent years, including an updated version of GrimAge57; FitAge58, which tracks individual differences in physical fitness; CheekAge59, a clock trained on a buccal cell dataset of more than 8,000 adults, which shows strong predictive ability across tissue types60; and DamAge and AdaptAge61, which aim to profile detrimental and beneficial DNAm changes with age. These clocks differ substantially in the number of CpGs that they use.

Depending on the outcome being predicted (for example, risk of all-cause mortality versus current physical health) and the cohort characteristics of the training dataset, second-generation clocks can capture different health-related and disease-related aspects of ageing. In addition, multiple disease combinations could lead to the same epigenetic age estimate, although the individual diseases (for example, cancer, cardiovascular disease or neurodegenerative disease) might differentially affect an individual’s well-being. The lack of a consensus phenotypic definition of biological ageing is a clear limitation for the development of epigenetic clocks. Bespoke disease predictors or clocks might help to overcome this limitation; however, challenges will remain for outcomes such as dementia, which has a long latency period and no precisely defined age of onset. Challenges also exist for precisely measured outcomes, such as cause-specific mortality, as dementia is commonly under-reported on death certificates62,63.

Further details on the construction of epigenetic clocks, including those derived from alternative methodologies, have been reviewed elsewhere64. This previous article describes deep learning approaches as well as clocks based on epigenetic outliers and stochastic epigenetic mutations (‘noise clocks’) and clocks applied to single-cell data.

Associations with cognitive functioning, dementia and lifestyle risk factors

Given the relatively large number of epigenetic clocks and possible cognitive and brain health outcomes, synthesizing the evidence for their associations is complex. With study sample sizes typically being in the low thousands, substantial heterogeneity is encountered when aggregating results. Nonetheless, some systematic reviews have been conducted.

In relation to dementia, mild cognitive impairment and cognitive function, Zhou et al.65 compiled evidence from 30 studies across leading clocks at the time of publication in 2022, which included the Horvath, Hannum, GrimAge, PhenoAge and DunedinPACE clocks. For the dementia phenotype, which included multiple neurodegenerative disorders, sample sizes were small (n <1,000 in each case). Evidence for robust associations between accelerated ageing and cognitive outcomes was limited. The authors highlighted 20 studies that explored clocks in relation to cognitive function in adulthood. In the largest single study (African American subset of the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities cohort; n = 2,157), accelerated ageing based on the Hannum clock correlated with lower scores on a test of word fluency66. However, consistent with the lack of data on dementia and neurodegenerative disease, no clear patterns were observed when the results across all studies, many of which considered different clocks and cognitive test outcomes, were combined.

A paper by McCrory et al.67, which was published in 2021 but was not included in the systematic review, produced similarly mixed findings. Using data from 490 participants of the Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA), the authors observed that age acceleration according to the Hannum and Horvath clocks was not associated with cognitive function or other measures of health. By contrast, PhenoAge and GrimAge were associated with global cognitive scores (Montreal Cognitive Assessment and Mini-Mental State Examination) but not with reaction time measures in minimally adjusted models. The significant associations with GrimAge acceleration persisted with more stringent covariate inclusion. A further study that incorporated the TILDA dataset, in addition to cohorts from the USA and Northern Ireland, showed similar results, with PhenoAge, GrimAge and DunedinPACE all being linked cross-sectionally to lower cognitive test scores68. A systematic review by Chervova et al., which was published in 2024, highlighted mixed associations between epigenetic ageing and cognitive function: GrimAge and PhenoAge acceleration was linked to reduced cognitive abilities but the findings were null for Hannum and Horvath acceleration69. However, a meta-analysis conducted as part of the same study found no association between GrimAge acceleration and dementia.

To investigate clock associations with brain MRI outcomes, Whitman et al. compiled data from three datasets — the Dunedin cohort, the Framingham Heart Study (FHS) and the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) — totalling 3,380 observations from 2,322 individuals70. These data spanned mid-life to late-life adulthood with mean ages of 45, 63 and 75 years (Dunedin, FHS and ADNI cohorts, respectively). They focused on associations between five epigenetic clocks (DunedinPACE, Horvath, Hannum, PhenoAge and GrimAge) and MRI-based brain structural measures. Acceleration of the DunedinPACE and GrimAge clocks most consistently correlated with lower total brain and hippocampal volumes, greater white matter lesion volumes, and cortical thinning.

Before the Chervova et al. review and meta-analysis69, Oblak et al.71 presented a comprehensive systematic review of clock associations with a broad range of biological, social and environmental factors. They considered findings from 156 studies, spanning dozens of phenotypic associations and considering 34 potential epigenetic clocks, 28 of which were first-generation predictors of chronological age. The Hannum, Horvath, PhenoAge and GrimAge clocks were used most frequently. Of the 57 factors that were included in the meta-analysis, 36 showed statistically significant associations. Several were well-known risk factors or correlates of brain health; for example, acceleration of the first-generation Hannum and Horvath clocks was associated with higher alcohol consumption and male sex. Acceleration of the Horvath clock was also linked to higher BMI. Acceleration of the second-generation PhenoAge and GrimAge clocks was associated with lower education, reduced physical activity and smoking. The GrimAge association with smoking was not surprising, as a methylation-based surrogate for smoking was included in the construction of this clock. One of the key differences reported between the first-generation and second-generation clocks was that the latter were associated with psychiatric traits: both DNAm PhenoAge and GrimAge were linked to schizophrenia, and GrimAge was also associated with depression. In general, the effect sizes were of greater magnitude for GrimAge than for the other clocks.

Although studies have generally demonstrated trends towards correlations between blood-based DNAm age or age acceleration and measures of cognitive ability72,73,74,75,76,77, few have had the means to simultaneously interrogate the confounding influence of neuropathology on these relationships. In one study, however, the Horvath and PhenoAge clocks were calculated in post-mortem dorsolateral prefrontal cortex tissue samples from participants in the Religious Orders Study and the Rush Memory and Aging Project32 (ROSMAP). Around 50% of the association between DNAm age and cognitive ability (global and episodic memory) was accounted for by variation in neuropathological features, including amyloid pathology.

Beyond clocks

Epigenetic biomarkers for lifestyle risk factors

In addition to direct associations between epigenetic clocks and cognitive health or neurodegenerative disease outcomes, studies have explored clock associations with risk factors that influence brain health over the life course. As highlighted in the Lancet Commission on Dementia in 2024 (ref. 78), many well-established and potentially modifiable risk factors affect late-life brain health, including obesity, alcohol consumption, smoking, high blood pressure and high LDL cholesterol levels.

EWASs and methylome-wide association studies have linked thousands of CpGs to these modifiable risk factors. Analogous to the development of epigenetic clocks, multi-CpG signatures have also been generated to provide surrogate measures of specific traits and behaviours79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88. This approach is particularly valuable for measures such as smoking or alcohol consumption, which are typically assessed through self-report questionnaires, or for BMI, which is a somewhat crude measure of general metabolic health. Crucially, studies have shown that the methylation-based predictors, sometimes termed EpiScores or methylation risk scores, can yield larger effect sizes than the measured variables when studied in relation to relevant measures of health and disease89,90.

Epigenetic biomarkers of plasma proteins

The inclusion of EpiScores for plasma proteins in the construction of GrimAge57 hints at a complex interplay between healthy ageing, the methylome and the proteome. The proteome has been under increasing focus for the development of disease biomarkers in recent years, and protein biomarkers for dementia are on the horizon. UK Biobank studies demonstrated that individual proteins, such as glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), latent-transforming growth factor β-binding protein 2 (LTBP2) and neurofilament light chain (NfL), as well as composite protein scores were associated with the risk of all-cause dementia91,92,93. Notably, data from the UK Biobank study indicated that plasma GFAP and NfL levels were elevated up to 15 years before a dementia diagnosis was made94. Protein levels themselves offer considerable potential as biomarkers, but DNAm proxies for proteins might reflect similar associations with health outcomes95,96,97. However, current findings57,95 suggest that proxies do not exist for all proteins. As larger cohorts generate paired DNAm and plasma proteomics (for example, ~10,000 proteins are characterized on the latest SomaScan platform98), it will be important to establish the scenarios where EpiScore development is feasible and where these scores complement or outperform measured protein signatures for the prediction of cognitive or brain health outcomes.

Evidence is accumulating that protein EpiScores have particular value as markers of inflammation. The negative health implications of chronic low-grade inflammation (so-called ‘inflammaging’) are increasingly recognized in the context of both neurological and non-neurological disease, and C-reactive protein (CRP) has emerged as a putative biomarker of this process99,100,101,102,103,104. However, the sensitivity of plasma CRP levels to acute events such as infection and injury, reduces the reliability of single-time-point measurements as markers of longer-term inflammation105,106.

EpiScores might help to mitigate the effects of short-term fluctuations in CRP levels. Several studies have adopted this approach, using regression weights from a CRP EWAS (much as a polygenic score uses genome-wide association study summary statistics) to build CRP EpiScores in independent samples and testing their associations with a host of health outcomes100,103,104. These EpiScores sometimes outperform those based on plasma or serum CRP levels, exhibiting stronger correlations with traits, including cognitive and brain MRI measures (for example, global and regional tissue volumes and white matter hyperintensities) in older adults102,105. At the other end of the lifespan, higher CRP EpiScores at birth have been linked to poorer general cognitive function at the age of 7 years107 and also correlate with the degree of perinatal inflammatory disease burden and adverse brain macrostructural outcomes (for example, reduced white matter, deep grey matter, hippocampal and amygdala volumes, and white matter microstructural characteristics across multiple pathways) among preterm compared with term-born neonates108. A CRP EpiScore applied to salivary DNAm data from over 1,000 children aged 8–19 years was associated with reduced cognitive measures of speed, executive function, reasoning and verbal comprehension109. In a study published in 2024, Hillary et al. explored several different methods to generate CRP EpiScores, which were tested across diverse populations104. The authors demonstrated that the EpiScore outperformed both assay-based CRP measurements and CRP genetic risk scores with respect to associations with health outcomes, including cardiovascular disease and stroke104.

We have presented promising findings for an EpiScore based on growth-differentiation factor 15 (GDF15)96, an inflammatory protein that is associated with multiple incident disease outcomes, including Alzheimer disease dementia, vascular dementia, ischaemic stroke and all-cause mortality, according to data from the UK Biobank93. Methylation data from the Generation Scotland cohort were used to train the predictor, and the resulting GDF15 EpiScore explained 8.9% of the variance in the measured protein in the external Lothian Birth Cohort 1936 (ref. 96). The EpiScore and measured protein also showed concordance with incident all-cause dementia and ischaemic stroke associations in a holdout set from Generation Scotland. Interestingly, a different GDF15 EpiScore was included in the derivation of GrimAge53. This score explained 5.6% of the variance in the measured protein in the Lothian Birth Cohort 1936 and had a correlation of only 0.32 (Pearson correlation) with the Generation Scotland-derived GDF15 EpiScore96.

The methylation proxy approach has been extended to other proteins and health outcomes; for example, Gadd et al. created 109 protein EpiScores, which demonstrated 137 incident disease associations, including stroke95. Eighteen of these EpiScores were also linked to general cognitive function in a meta-analysis across three Scottish cohorts110 but showed weaker associations with incident dementia.

Epigenetic biomarkers for cognitive function

Few large-scale epigenome-wide studies of cognitive function have been conducted. A meta-analysis of 11 cohorts (n = 2,557–6,809) and two studies using data from Generation Scotland, one involving 9,162 and the other involving 18,264 participants, identified only a handful of candidate loci in adults5,111,112. The lead loci from the second study did not overlap with those from the meta-analysis or with findings from Alzheimer disease EWASs. However, the three studies applied different analytical approaches: the first considered individual cognitive tests, the second used a principal components analysis-derived general cognitive factor and the third used a multivariate regression approach to model all cognitive tests simultaneously.

By contrast to the limited findings for individual CpG correlates of cognitive function, the two Generation Scotland studies5,111 included variance components analyses, which showed that up to 73% of the variance in a test of vocabulary could be explained by all CpGs on the EPIC array. This finding suggests that, in relation to blood-based DNAm, cognitive function is likely to be a highly polygenic trait involving many CpGs with small effects. This idea was supported by the two Generation Scotland studies through the creation of cognitive EpiScores5,111. When these scores were tested in the external Lothian Birth Cohort of 1936, 3.4% of the variance in general cognitive function was explained by the EpiScore trained on 9,162 individuals, compared with >6% for the EpiScore trained on 18,264 participants using the multivariate regression framework.

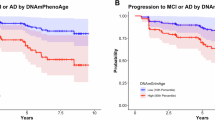

The EpiScore that was trained on 9,162 Scottish adults was also applied to a cohort of mixed-ancestry children and teenagers living in Texas, USA, where it captured over 11% of the variance of individual differences in performance on a mathematics test109. The same EpiScore of cognitive function showed weaker but directionally consistent associations with measures of brain imaging, lifestyle, and general health and with levels of proteins compared with associations with measured cognitive function5. Machine learning techniques have also been used to derive a multivariate methylation risk score from whole-blood DNAm, based on dementia risk factors and cognitive function, to predict the development of cognitive impairment6. These scores enhanced the prediction of mild cognitive impairment compared with CSF biomarkers or polygenic risk scores, demonstrating the potential benefit of incorporating epigenetic scores to current risk prediction strategies.

Similar to the literature in adults, EWASs of cognitive function in neonates, infants and adolescents have been relatively small-scale efforts113. However, work from the Pregnancy and Childhood Epigenetics (PACE) consortium114, a collective that is measuring DNAm in over 40 paediatric cohorts, demonstrates a shift towards collaborative efforts to scale up power, generalizability and comparability in epigenetic research115.

Mirroring the small-scale EWASs of cognitive function across the life course, there has been a limited focus on the direct relationship between DNAm and neurologically relevant traits, as measured through brain MRI. One of the largest efforts to date is an ENIGMA Epigenetics Working Group consortium, which presented an EWAS of three subcortical volumes — thalamus, nucleus accumbens and hippocampus — across 11 cohorts116 (n = 3,337). Two loci were identified for the hippocampus: cg26927218, annotated to BAIAP2, which encodes a synaptic protein expressed in this region; and cg17858098, annotated to ECH1, which encodes an enzyme involved in fatty acid oxygenation. No other CpGs were identified in the main EWAS analyses. A larger study of white matter hyperintensity volumes across 14 community-dwelling adult cohorts (n = 9,732) found 12 epigenome-wide significant CpGs and 46 region-based DNAm associations117. Overall, studies of the blood methylome in relation to cognitive function or structural brain measures have been relatively sparse.

Limitations and future directions

In this Review, we have focused exclusively on CpG DNAm signatures but other epigenetic features and modifications, such as hydroxymethylation, histone modifications and changes in chromatin accessibility, might also exhibit ageing-related and brain-relevant patterns. Currently, however, array-based CpG methylation remains the most commonly measured, and therefore the best characterized, epigenetic modification in large and diverse population-based cohorts. In 2024, Oxford Nanopore Technology announced plans to sequence 50,000 samples from the UK Biobank cohort to generate an epigenetic map of the human genome118. Their sequencing approach will allow researchers to interrogate ~30 million CpG methylation sites — compared with the ~1 million sites captured by Illumina arrays — as well as hydroxymethylation. Future epigenetic biomarker work could extend to the translation of findings from bulk tissue, such as whole blood, to single-cell data.

Several technical, practical and ethical challenges surround the generalization of DNAm biomarkers across diverse populations and their translation into clinical practice. DNAm measurements can vary across platforms119,120, and epigenetic clocks can fluctuate over the course of a day121. With regard to generalization, the DunedinPACE clock was trained using a subset of ~81,000 CpGs that were present on both the 450 K and the EPIC methylation arrays and had good test–retest reliability56,122 (intraclass correlation >0.4). Epigenetic drift — that is, stochastic DNAm changes with ageing — might introduce noise into clock predictions, particularly in older populations, and could affect the robustness of biomarkers123,124,125. Arrays also provide relative, as opposed to absolute, quantification of methylation, which presents challenges when attempting to interpret data at the individual level or when trying to project an individual’s EpiScores or clock estimates onto a reference population. Furthermore, additional work is required to determine the extent to which EpiScores and epigenetic clocks translate across diverse populations. Much of the existing literature, particularly on the training of biomarkers, has focused on European ancestry cohorts126.

Despite their utility for capturing broad, systemic ageing, epigenetic clocks by design are lacking in disease specificity. As the field moves forward and as larger biobank cohorts generate DNAm data, it might become possible to build a panel of bespoke DNAm-based predictors for specific diseases or traits. This approach, which will rely on consensus definitions for disease outcomes and sufficient numbers of cases for training and testing, could lead to more interpretable and actionable findings (for example, more targeted screening and risk stratification) than a single predictor trained on an amalgam of diverse markers of ageing such as second-generation and third-generation epigenetic clocks. Another priority is to investigate the potential added value of clocks and EpiScores on top of established biomarkers for neurodegeneration such as amyloid and tau imaging or fluid biomarkers. Comparisons between these measures, as well as with brain-specific epigenetic alterations, where available, will help us to determine the contexts in which blood-based biomarkers are most valuable.

Overcoming the various challenges will be essential if epigenetic clocks — whether disease-specific or as general markers of ageing — are to be translated into clinical settings. We theorize that the most likely application of epigenetic biomarkers would be for disease risk stratification, where they could augment existing tools that are used to enable prevention and risk reduction.

Conclusions

A host of epigenetic clocks have been and continue to be developed to track different elements of chronological and biological ageing. Although a faster tick rate for some clocks is associated with specific health outcomes, the relationships do not robustly extend to dementia at present. Importantly, current epigenetic clocks are more likely to be biomarkers than causal agents in disease pathogenesis and it is perhaps more important for clocks to be trained on peripheral biosamples than on those that reflect the molecular underpinnings of neurodegeneration. The development and application of EpiScores of cognitive function, lifestyle and protein measures that represent risk factors for neurodegeneration might also offer an effective way to track brain health across the life course.

References

Bell, C. G. et al. DNA methylation aging clocks: challenges and recommendations. Genome Biol. 20, 249 (2019).

Horvath, S. & Raj, K. DNA methylation-based biomarkers and the epigenetic clock theory of ageing. Nat. Rev. Genet. 19, 371–384 (2018).

Lu, A. T. et al. Universal DNA methylation age across mammalian tissues. Nat. Aging 3, 1144–1166 (2023).

Li, C. Z. et al. Epigenetic predictors of species maximum life span and other life-history traits in mammals. Sci. Adv. 10, eadm7273 (2024).

McCartney, D. L. et al. Blood-based epigenome-wide analyses of cognitive abilities. Genome Biol. 23, 26 (2022).

Koetsier, J. et al. Blood-based multivariate methylation risk score for cognitive impairment and dementia. Alzheimers Dement. 20, 6682–6698 (2024).

Garagnani, P. et al. Methylation of ELOVL2 gene as a new epigenetic marker of age. Aging Cell 11, 1132–1134 (2012).

Bernabeu, E. et al. Refining epigenetic prediction of chronological and biological age. Genome Med. 15, 12 (2023).

Bibikova, M. et al. Genome-wide DNA methylation profiling using Infinium® assay. Epigenomics 1, 177–200 (2009).

Pidsley, R. et al. Critical evaluation of the Illumina MethylationEPIC BeadChip microarray for whole-genome DNA methylation profiling. Genome Biol. 17, 208 (2016).

Illumina. Infinium HumanMethylation450 BeadChip Product Files. Data Sheet https://www.illumina.com/content/dam/illumina-marketing/documents/products/datasheets/datasheet_humanmethylation450.pdf (2012).

Illumina. Infinium MethylationEPIC v2.0 Kit BeadChip. Data Sheet https://emea.illumina.com/content/dam/illumina/gcs/assembled-assets/marketing-literature/infinium-methylation-epic-data-sheet-m-gl-01156/infinium-methylation-epic-data-sheet-m-gl-01156.pdf (2022).

Goldberg, D. C. et al. Scalable screening of ternary-code DNA methylation dynamics associated with human traits. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.05.17.594606 (2025).

Bocklandt, S. et al. Epigenetic predictor of age. PLoS ONE 6, e14821 (2011).

Koch, C. M. & Wagner, W. Epigenetic-aging-signature to determine age in different tissues. Aging 3, 1018–1027 (2011).

Hannum, G. et al. Genome-wide methylation profiles reveal quantitative views of human aging rates. Mol. Cell 49, 359–367 (2013).

Horvath, S. DNA methylation age of human tissues and cell types. Genome Biol. 14, R115 (2013).

Marioni, R. E. et al. DNA methylation age of blood predicts all-cause mortality in later life. Genome Biol. 16, 25 (2015).

Chen, B. H. et al. DNA methylation-based measures of biological age: meta-analysis predicting time to death. Aging 8, 1844–1865 (2016).

Shireby, G. L. et al. Recalibrating the epigenetic clock: implications for assessing biological age in the human cortex. Brain 143, 3763–3775 (2020).

Murthy, M. et al. Epigenetic age acceleration is associated with oligodendrocyte proportions in MSA and control brain tissue. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 49, e12872 (2023).

Wang, Y., Grant, O. A., Zhai, X., Mcdonald-Maier, K. D. & Schalkwyk, L. C. Insights into ageing rates comparison across tissues from recalibrating cerebellum DNA methylation clock. GeroScience 46, 39–56 (2024).

Thrush, K. L. et al. Aging the brain: multi-region methylation principal component based clock in the context of Alzheimer’s disease. Aging 14, 5641 (2022).

Grodstein, F. et al. Characteristics of epigenetic clocks across blood and brain tissue in older women and men. Front. Neurosci. 14, 555307 (2021).

Grodstein, F. et al. The association of epigenetic clocks in brain tissue with brain pathologies and common aging phenotypes. Neurobiol. Dis. 157, 105428 (2021).

Mendizabal, I. et al. Cell type-specific epigenetic links to schizophrenia risk in the brain. Genome Biol. 20, 135 (2019).

Hansen, D. V., Hanson, J. E. & Sheng, M. Microglia in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Cell Biol. 217, 459–472 (2017).

Shireby, G. et al. DNA methylation signatures of Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology in the cortex are primarily driven by variation in non-neuronal cell-types. Nat. Commun. 13, 5620 (2022).

Francis, P. T., Costello, H. & Hayes, G. M. Brains for Dementia Research: evolution in a longitudinal brain donation cohort to maximize current and future value. J. Alzheimers Dis. 66, 1635–1644 (2018).

Coninx, E. et al. Hippocampal and cortical tissue-specific epigenetic clocks indicate an increased epigenetic age in a mouse model for Alzheimer’s disease. Aging 12, 20817 (2020).

Heinsberg, L. W., Liu, D., Shaffer, J. R., Weeks, D. E. & Conley, Y. P. Characterization of cerebrospinal fluid DNA methylation age during the acute recovery period following aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Epigenetics Commun. 1, 2 (2021).

Levine, M. E., Lu, A. T., Bennett, D. A. & Horvath, S. Epigenetic age of the pre-frontal cortex is associated with neuritic plaques, amyloid load, and Alzheimer’s disease related cognitive functioning. Aging 7, 1198 (2015).

Lu, A. T. et al. Genetic architecture of epigenetic and neuronal ageing rates in human brain regions. Nat. Commun. 8, 15353 (2017).

Horvath, S. et al. The cerebellum ages slowly according to the epigenetic clock. Aging 7, 294 (2015).

Knight, A. K. et al. An epigenetic clock for gestational age at birth based on blood methylation data. Genome Biol. 17, 206 (2016).

Johnson, S. & Marlow, N. Early and long-term outcome of infants born extremely preterm. Arch. Dis. Child. 102, 97–102 (2017).

Sullivan, G. et al. Preterm birth is associated with immune dysregulation which persists in infants exposed to histologic chorioamnionitis. Front. Immunol. 12, 722489 (2021).

Bach, A. M. et al. Systemic inflammation during the first year of life is associated with brain functional connectivity and future cognitive outcomes. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 53, 101041 (2021).

Colwell, M. L., Townsel, C., Petroff, R. L., Goodrich, J. M. & Dolinoy, D. C. Epigenetics and the exposome: DNA methylation as a proxy for health impacts of prenatal environmental exposures. Exposome 3, osad001 (2023).

Bohlin, J. et al. Prediction of gestational age based on genome-wide differentially methylated regions. Genome Biol. 17, 207 (2016).

Haftorn, K. L. et al. An EPIC predictor of gestational age and its application to newborns conceived by assisted reproductive technologies. Clin. Epigenetics 13, 82 (2021).

Polinski, K. J. et al. Epigenetic gestational age and the relationship with developmental milestones in early childhood. Hum. Mol. Genet. 32, 1565–1574 (2023).

Lee, Y. et al. Placental epigenetic clocks: estimating gestational age using placental DNA methylation levels. Aging 11, 4238 (2019).

Mayne, B. T. et al. Accelerated placental aging in early onset preeclampsia pregnancies identified by DNA methylation. Epigenomics 9, 279–289 (2017).

McEwen, L. M. et al. The PedBE clock accurately estimates DNA methylation age in pediatric buccal cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 117, 23329–23335 (2020).

Gomaa, N. et al. Association of pediatric buccal epigenetic age acceleration with adverse neonatal brain growth and neurodevelopmental outcomes among children born very preterm with a neonatal infection. JAMA Netw. Open 5, e2239796 (2022).

Graw, S. et al. NEOage clocks-epigenetic clocks to estimate post-menstrual and postnatal age in preterm infants. Aging 13, 23527 (2021).

Lapehn, S. & Paquette, A. G. The placental epigenome as a molecular link between prenatal exposures and fetal health outcomes through the DOHaD hypothesis. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 9, 490–501 (2022).

Mill, J. & Heijmans, B. T. From promises to practical strategies in epigenetic epidemiology. Nat. Rev. Genet. 14, 585–594 (2013).

Smith, A. K. et al. DNA extracted from saliva for methylation studies of psychiatric traits: evidence tissue specificity and relatedness to brain. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 168, 36–44 (2015).

Theda, C. et al. Quantitation of the cellular content of saliva and buccal swab samples. Sci. Rep. 8, 6944 (2018).

Zhang, Q. et al. Improved precision of epigenetic clock estimates across tissues and its implication for biological ageing. Genome Med. 11, 54 (2019).

Lu, A. T. et al. DNA methylation GrimAge strongly predicts lifespan and healthspan. Aging 11, 303–327 (2019).

Levine, M. E. et al. An epigenetic biomarker of aging for lifespan and healthspan. Aging 10, 573–591 (2018).

Belsky, D. W. et al. Quantification of the pace of biological aging in humans through a blood test, the DunedinPoAm DNA methylation algorithm. eLife 9, e54870 (2020).

Belsky, D. W. et al. DunedinPACE, a DNA methylation biomarker of the pace of aging. eLife 11, e73420 (2022).

Lu, A. T. et al. DNA methylation GrimAge version 2. Aging 14, 9484–9549 (2022).

McGreevy, K. M. et al. DNAmFitAge: biological age indicator incorporating physical fitness. Aging 15, 3904–3938 (2023).

Shokhirev, M. N., Torosin, N. S., Kramer, D. J., Johnson, A. A. & Cuellar, T. L. CheekAge: a next-generation buccal epigenetic aging clock associated with lifestyle and health. GeroScience 46, 3429–3443 (2024).

Shokhirev, M. N. et al. CheekAge, a next-generation epigenetic buccal clock, is predictive of mortality in human blood. Front. Aging 5, 1460360 (2024).

Ying, K. et al. Causality-enriched epigenetic age uncouples damage and adaptation. Nat. Aging 4, 231–246 (2024).

Stokes, A. C. et al. Estimates of the association of dementia with US mortality levels using linked survey and mortality records. JAMA Neurol. 77, 1543–1550 (2020).

Gao, L. et al. Accuracy of death certification of dementia in population-based samples of older people: analysis over time. Age Ageing 47, 589–594 (2018).

Teschendorff, A. E. & Horvath, S. Epigenetic ageing clocks: statistical methods and emerging computational challenges. Nat. Rev. Genet. 26, 350–368 (2025).

Zhou, A. et al. Epigenetic aging as a biomarker of dementia and related outcomes: a systematic review. Epigenomics 14, 1125–1138 (2022).

Bressler, J. et al. Epigenetic age acceleration and cognitive function in African American adults in midlife: the Atherosclerosis risk in communities study. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 75, 473–480 (2020).

McCrory, C. et al. GrimAge outperforms other epigenetic clocks in the prediction of age-related clinical phenotypes and all-cause mortality. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 76, 741–749 (2021).

Crimmins, E. M. et al. Epigenetic clocks relate to four age-related health outcomes similarly across three countries. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glaf036 (2025).

Chervova, O. et al. Breaking new ground on human health and well-being with epigenetic clocks: a systematic review and meta-analysis of epigenetic age acceleration associations. Ageing Res. Rev. 102, 102552 (2024).

Whitman, E. T. et al. A blood biomarker of the pace of aging is associated with brain structure: replication across three cohorts. Neurobiol. Aging 136, 23–33 (2024).

Oblak, L., van der Zaag, J., Higgins-Chen, A. T., Levine, M. E. & Boks, M. P. A systematic review of biological, social and environmental factors associated with epigenetic clock acceleration. Ageing Res. Rev. 69, 101348 (2021).

Marioni, R. E. et al. The epigenetic clock is correlated with physical and cognitive fitness in the Lothian Birth Cohort 1936. Int. J. Epidemiol. 44, 1388–1396 (2015).

Vaccarino, V. et al. Epigenetic age acceleration and cognitive decline: a twin study. J. Gerontol. Ser. A 76, 1854–1863 (2021).

Phyo, A. Z. Z. et al. Epigenetic age acceleration and cognitive performance over time in older adults. Alzheimers Dement. 16, e70010 (2024).

Ware, E. B. et al. Interplay of education and DNA methylation age on cognitive impairment: insights from the Health and Retirement Study. Geroscience https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-024-01356-0 (2024).

Blostein, F. et al. DNA methylation age acceleration is associated with incident cognitive impairment in the health and retirement study. J. Alzheimers Dis. 105, 966–976 (2025).

Gampawar, P., Veeranki, S. P. K., Petrovic, K.-E., Schmidt, R. & Schmidt, H. Epigenetic age acceleration is related to cognitive decline in the elderly: results of the Austrian stroke prevention study. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 79, 229–238 (2025).

Livingston, G. et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2024 report of the Lancet Standing Commission. Lancet 404, 572–628 (2024).

McCartney, D. L. et al. Epigenetic prediction of complex traits and death. Genome Biol. 19, 136 (2018).

Nabais, M. F. et al. An overview of DNA methylation-derived trait score methods and applications. Genome Biol. 24, 28 (2023).

Yousefi, P. D. et al. DNA methylation-based predictors of health: applications and statistical considerations. Nat. Rev. Genet. 23, 369–383 (2022).

Liu, C. et al. A DNA methylation biomarker of alcohol consumption. Mol. Psychiatry 23, 422–433 (2018).

Joehanes, R. et al. Epigenetic signatures of cigarette smoking. Circulation Cardiovasc. Genet. 9, 436–447 (2016).

Wahl, S. et al. Epigenome-wide association study of body mass index, and the adverse outcomes of adiposity. Nature 541, 81–86 (2017).

Richard, M. A. et al. DNA methylation analysis identifies loci for blood pressure regulation. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 101, 888–902 (2017).

Chybowska, A. D. et al. A blood- and brain-based EWAS of smoking. Nat. Commun. 16, 3210 (2025).

Smith, H. M. et al. DNA methylation-based predictors of metabolic traits in Scottish and Singaporean cohorts. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 112, 106–115 (2025).

Bernabeu, E. et al. Blood-based epigenome-wide association study and prediction of alcohol consumption. Clin. Epigenetics 17, 14 (2025).

Corley, J. et al. Epigenetic signatures of smoking associate with cognitive function, brain structure, and mental and physical health outcomes in the Lothian Birth Cohort 1936. Transl. Psychiatry 9, 248 (2019).

Hamilton, O. K. L. et al. An epigenetic score for BMI based on DNA methylation correlates with poor physical health and major disease in the Lothian Birth Cohort. Int. J. Obes. 43, 1795–1802 (2019).

Guo, Y. et al. Plasma proteomic profiles predict future dementia in healthy adults. Nat. Aging 4, 247–260 (2024).

Argentieri, M. A. et al. Proteomic aging clock predicts mortality and risk of common age-related diseases in diverse populations. Nat. Med. 30, 2450–2460 (2024).

Gadd, D. A. et al. Blood protein assessment of leading incident diseases and mortality in the UK Biobank. Nat. Aging 4, 939–948 (2024).

Wang, X., Shi, Z., Qiu, Y., Sun, D. & Zhou, H. Peripheral GFAP and NfL as early biomarkers for dementia: longitudinal insights from the UK Biobank. BMC Med. 22, 192 (2024).

Gadd, D. A. et al. Epigenetic scores for the circulating proteome as tools for disease prediction. eLife 11, e71802 (2022).

Gadd, D. A. et al. DNAm scores for serum GDF15 and NT-proBNP levels associate with a range of traits affecting the body and brain. Clin. Epigenetics 16, 124 (2024).

Carreras-Gallo, N. et al. Leveraging DNA methylation to create epigenetic biomarker proxies that inform clinical care: a new framework for precision medicine. Preprint at medRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.12.06.24318612 (2024).

Rooney, M. R. et al. Plasma proteomic comparisons change as coverage expands for SomaLogic and Olink. Preprint at medRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.07.11.24310161 (2024).

Liu, C. H. et al. Biomarkers of chronic inflammation in disease development and prevention: challenges and opportunities. Nat. Immunol. 18, 1175–1180 (2017).

Ligthart, S. et al. DNA methylation signatures of chronic low-grade inflammation are associated with complex diseases. Genome Biol. 17, 255 (2016).

Franceschi, C., Garagnani, P., Parini, P., Giuliani, C. & Santoro, A. Inflammaging: a new immune–metabolic viewpoint for age-related diseases. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 14, 576–590 (2018).

Conole, E. L. S. et al. DNA methylation and protein markers of chronic inflammation and their associations with brain and cognitive aging. Neurology 97, e2340–e2352 (2021).

Wielscher, M. et al. DNA methylation signature of chronic low-grade inflammation and its role in cardio-respiratory diseases. Nat. Commun. 13, 2408 (2022).

Hillary, R. F. et al. Blood-based epigenome-wide analyses of chronic low-grade inflammation across diverse population cohorts. Cell Genomics 4, 100544 (2024).

Stevenson, A. J. et al. Characterisation of an inflammation-related epigenetic score and its association with cognitive ability. Clin. Epigenetics 12, 113 (2020).

Verschoor, C. P., Vlasschaert, C., Rauh, M. J. & Paré, G. A DNA methylation based measure outperforms circulating CRP as a marker of chronic inflammation and partly reflects the monocytic response to long-term inflammatory exposure: a Canadian longitudinal study on aging analysis. Aging Cell 22, e13863 (2023).

Barker, E. D. et al. Inflammation-related epigenetic risk and child and adolescent mental health: a prospective study from pregnancy to middle adolescence. Dev. Psychopathol. 30, 1145–1156 (2018).

Conole, E. L. S. et al. Immuno-epigenetic signature derived in saliva associates with the encephalopathy of prematurity and perinatal inflammatory disorders. Brain Behav. Immun. 110, 322–338 (2023).

Raffington, L. et al. Socially stratified epigenetic profiles are associated with cognitive functioning in children and adolescents. Psychol. Sci. 34, 170–185 (2023).

Smith, H. M. et al. Epigenetic scores of blood-based proteins as biomarkers of general cognitive function and brain health. Clin. Epigenetics 16, 46 (2024).

Krätschmer, I. et al. Discovery of shared epigenetic pathways across human phenotypes. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.04.15.589547 (2024).

Marioni, R. E. et al. Meta-analysis of epigenome-wide association studies of cognitive abilities. Mol. Psychiatry 23, 2133–2144 (2018).

Caramaschi, D. et al. Meta-analysis of epigenome-wide associations between DNA methylation at birth and childhood cognitive skills. Mol. Psychiatry 27, 2126–2135 (2022).

Felix, J. F. et al. Cohort profile: pregnancy and childhood epigenetics (PACE) consortium. Int. J. Epidemiol. 47, 22–23u (2018).

Cecil, C. A., Neumann, A. & Walton, E. Epigenetics applied to child and adolescent mental health: progress, challenges and opportunities. JCPP Adv. 3, e12133 (2023).

Jia, T. et al. Epigenome-wide meta-analysis of blood DNA methylation and its association with subcortical volumes: findings from the ENIGMA epigenetics working group. Mol. Psychiatry 26, 3884–3895 (2021).

Yang, Y. et al. Epigenetic and integrative cross-omics analyses of cerebral white matter hyperintensities on MRI. Brain 146, 492–506 (2023).

UK Biobank. Landmark Genetics Partnership to Probe the Causes of Cancer and Dementia https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/learn-more-about-uk-biobank/news/landmark-genetics-partnership-to-probe-the-causes-of-cancer-and-dementia (2024).

Lussier, A. A. et al. Technical variability across the 450K, EPICv1, and EPICv2 DNA methylation arrays: lessons learned for clinical and longitudinal studies. Clin. Epigenetics 16, 166 (2024).

Zhuang, B. C. et al. Discrepancies in readouts between Infinium MethylationEPIC v2.0 and v1.0 reflected in DNA methylation-based tools: implications and considerations for human population epigenetic studies. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.07.02.600461 (2024).

Koncevičius, K. et al. Epigenetic age oscillates during the day. Aging Cell 23, e14170 (2024).

Sugden, K. et al. Patterns of reliability: assessing the reproducibility and integrity of DNA methylation measurement. Patterns 1, 100014 (2020).

Gentilini, D. et al. Stochastic epigenetic mutations (DNA methylation) increase exponentially in human aging and correlate with X chromosome inactivation skewing in females. Aging 7, 568–578 (2015).

Wang, Y. et al. Comprehensive longitudinal study of epigenetic mutations in aging. Clin. Epigenetics 11, 187 (2019).

Markov, Y., Levine, M. & Higgins-Chen, A. T. Reliable detection of stochastic epigenetic mutations and associations with cardiovascular aging. GeroScience 46, 5745–5765 (2024).

Watkins, S. H. et al. Epigenetic clocks and research implications of the lack of data on whom they have been developed: a review of reported and missing sociodemographic characteristics. Environ. Epigenetics 9, dvad005 (2023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors contributed equally to all aspects of the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

R.E.M. is a scientific advisor to the Epigenetic Clock Development Foundation. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Reviews Neurology thanks G. Liu and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Glossary

- Elastic net penalized regression

-

In regression scenarios with many predictor variables, one can derive a sparse or parsimonious solution whereby non-important predictors are assigned a regression weight of zero. Elastic net penalized regression is one of the most commonly applied approaches to do this in the context of generating epigenetic clocks.

- Multivariate regression

-

In multivariable linear regression, we consider one outcome and multiple predictor variables, whereas in multivariate regression, we simultaneously model multiple outcome variables. This approach helps us to determine whether a predictor variable has common or unique associations with different outcomes within a single regression model.

- Principal components analysis

-

A data reduction approach whereby one can consider correlated variables by their most common shared features. For example, instead of focusing on scores from ten different cognitive tests, the data could be realigned into a smaller number of variables that capture most of the variance across all ten tests. This might include a general ability component, which captures information for individuals who perform similarly well across all tests, followed by components that capture information across certain domains, for example, tests that assess memory performance.

- Variance components analyses

-

Instead of considering predictors as separate variables, we can ask whether the similarity in these predictors across individuals correlates with the outcome of interest. For example, do people with broadly similar DNA methylation patterns also show similarity in the outcome variable of interest?

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Conole, E.L.S., Robertson, J.A., Smith, H.M. et al. Epigenetic clocks and DNA methylation biomarkers of brain health and disease. Nat Rev Neurol 21, 411–421 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41582-025-01105-7

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41582-025-01105-7