Abstract

Galaxies in the early Universe that are bright at submillimetre wavelengths (submillimetre-bright galaxies) are forming stars at a rate roughly 1,000 times higher than the Milky Way. A large fraction of the new stars form in the central kiloparsec of the galaxy1,2,3, a region that is comparable in size to the massive, quiescent galaxies found at the peak of cosmic star-formation history4 and the cores of present-day giant elliptical galaxies. The physical and kinematic properties inside these compact starburst cores are poorly understood because probing them at relevant spatial scales requires extremely high angular resolution. Here we report observations with a linear resolution of 550 parsecs of gas and dust in an unlensed, submillimetre-bright galaxy at a redshift of z = 4.3, when the Universe was less than two billion years old. We resolve the spatial and kinematic structure of the molecular gas inside the heavily dust-obscured core and show that the underlying gas disk is clumpy and rotationally supported (that is, its rotation velocity is larger than the velocity dispersion). Our analysis of the molecular gas mass per unit area suggests that the starburst disk is gravitationally unstable, which implies that the self-gravity of the gas is stronger than the differential rotation of the disk and the internal pressure due to stellar-radiation feedback. As a result of the gravitational instability in the disk, the molecular gas would be consumed by star formation on a timescale of 100 million years, which is comparable to gas depletion times in merging starburst galaxies5.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Swinbank, A. M. et al. Intense star formation within resolved compact regions in a galaxy at z = 2.3. Nature 464, 733–736 (2010).

Ikarashi, S. et al. Compact starbursts in z ~ 3–6 submillimeter galaxies revealed by ALMA. Astrophys. J. 810, 133 (2015).

Simpson, J. M. et al. The SCUBA-2 cosmology legacy survey: ALMA resolves the rest-frame far-infrared emission of sub-millimeter galaxies. Astrophys. J. 799, 81 (2015).

van Dokkum, P. et al. Forming compact massive galaxies. Astrophys. J. 813, 23 (2015).

Kennicutt, R. C. Jr. The global Schmidt law in star-forming galaxies. Astrophys. J. 498, 541–552 (1998).

Hughes, D. H. et al. High-redshift star formation in the Hubble Deep Field revealed by a submillimetre-wavelength survey. Nature 394, 241–247 (1998).

Barger, A. J. et al. Submillimetre-wavelength detection of dusty star-forming galaxies at high redshift. Nature 394, 248–251 (1998).

Chapman, S. C. et al. A redshift survey of the submillimeter galaxy population. Astrophys. J. 622, 772–796 (2005).

Bothwell, M. S. et al. A survey of molecular gas in luminous sub-millimetre galaxies. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 429, 3047–3067 (2013).

Ivison, R. J. et al. Herschel-ATLAS: a binary HyLIRG pinpointing a cluster of starbursting protoellipticals. Astrophys. J. 772, 137 (2013).

Tacconi, L. J. et al. Submillimeter galaxies at z ~ 2: evidence for major mergers and constraints on lifetimes, IMF, and CO-H2 conversion factor. Astrophys. J. 680, 246–262 (2008).

Hodge, J. A. et al. Evidence for a clumpy, rotating gas disk in a submillimeter galaxy at z = 4. Astrophys. J. 760, 11 (2012).

Iono, D. et al. Clumpy and extended starbursts in the brightest unlensed submillimeter galaxies. Astrophys. J. 829, L10 (2016).

Tadaki, K.-i. et al. Bulge-forming galaxies with an extended rotating disk at z ~ 2. Astrophys. J. 834, 135 (2017).

Swinbank, A. M. et al. ALMA resolves the properties of star-forming regions in a dense gas disk at z ~ 3. Astrophys. J. 806, L17 (2015).

Sharda, P. et al. Testing star formation laws in a starburst galaxy at redshift 3 resolved with ALMA. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 477, 4380–4390 (2018).

Bolatto, A. D. et al. The resolved properties of extragalactic giant molecular clouds. Astrophys. J. 686, 948–965 (2008).

Cappellari, M. Structure and kinematics of early-type galaxies from integral field spectroscopy. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 54, 597–665 (2016).

Veale, M. et al. The MASSIVE survey – V. Spatially resolved stellar angular momentum, velocity dispersion, and higher moments of the 41 most massive local early-type galaxies. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 464, 356–384 (2017).

Naab, T. et al. The ATLAS3D project – XXV. Two-dimensional kinematic analysis of simulated galaxies and the cosmological origin of fast and slow rotators. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 444, 3357–3387 (2014).

Genzel, R. et al. The Sins survey of z ~ 2 galaxy kinematics: properties of the giant star-forming clumps. Astrophys. J. 733, 101 (2011).

Bournaud, F. et al. The long lives of giant clumps and the birth of outflows in gas-rich galaxies at high-redshift. Astrophys. J. 780, 57–75 (2014).

Mandelker, N. et al. The population of giant clumps in simulated high-z galaxies: in situ and ex situ migration and survival. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 443, 3675–3702 (2014).

Genzel, R. et al. The SINS/zC-SINF survey of z ~ 2 galaxy kinematics: evidence for gravitational quenching. Astrophys. J. 785, 75 (2014).

Thompson, T. et al. Radiation pressure-supported starburst disks and active galactic nucleus fueling. Astrophys. J. 630, 167–185 (2005).

Cacciato, M. et al. Evolution of violent gravitational disc instability in galaxies: late stabilization by transition from gas to stellar dominance. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 421, 818–831 (2012).

Tacconi, L. J. et al. Phibss: molecular gas content and scaling relations in z ~ 1–3 massive, main-sequence star-forming galaxies. Astrophys. J. 768, 74 (2013).

Narayanan, D. et al. The star-forming molecular gas in high-redshift submillimetre galaxies. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 400, 1919–1935 (2009).

Ueda, J. et al. Cold molecular gas in merger remnants. I. Formation of molecular gas disks. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 214, 1 (2014).

Dekel, A. et al. Cold streams in early massive hot haloes as the main mode of galaxy formation. Nature 457, 451–454 (2009).

Scott, K. B. et al. AzTEC millimetre survey of the COSMOS field – I. Data reduction and source catalogue. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 385, 2225–2238 (2008).

Yun, M. S. et al. Early science with the Large Millimeter Telescope: CO and [C ii] emission in the z = 4.3 AzTEC J095942.9+022938 (COSMOS AzTEC-1). Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 454, 3485–3499 (2015).

Toft, S. et al. Submillimeter galaxies as progenitors of compact quiescent galaxies. Astrophys. J. 782, 68 (2014).

Chabrier, G. The galactic disk mass function: reconciliation of the Hubble Space Telescope and nearby determinations. Astrophys. J. 586, L133–L136 (2003).

McMullin, J. P., Waters, B., Schiebel, D., Young, W. & Golap, K. CASA architecture and applications. ASP Conf. Ser. 376, 127–130 (2007).

Smolčić, V. et al. The redshift and nature of AzTEC/COSMOS 1: a starburst galaxy at z = 4.6. Astrophys. J. 731, L27 (2011).

Laigle, C. et al. The COSMOS2015 catalog: exploring the 1 < z < 6 universe with half a million galaxies. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 24, 224 (2016).

Roseboom, I. G. et al. The Herschel multi-tiered extragalactic survey: SPIRE-mm photometric redshifts. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 419, 2758–2773 (2012).

Oliver, S. J. et al. The Herschel multi-tiered extragalactic survey: HerMES. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 424, 1614–1635 (2012).

Smolčić, V. et al. The VLA-COSMOS 3 GHz large project: continuum data and source catalog release. Astron. Astrophys. 602, A1 (2017).

da Cunha, E., Charlot, S. & Elbaz, D. A simple model to interpret the ultraviolet, optical and infrared emission from galaxies. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 388, 1595–1617 (2008).

da Cunha, E. et al. An ALMA survey of sub-millimeter galaxies in the extended Chandra deep field south: physical properties derived from ultraviolet-to-radio modeling. Astrophys. J. 806, 110 (2015).

Bruzual, G. & Charlot, S. Stellar population synthesis at the resolution of 2003. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 344, 1000–1028 (2003).

Papadopoulos, P. P., Thi, W.-F. & Viti, S. C i lines as tracers of molecular gas, and their prospects at high redshifts. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 351, 147–160 (2004).

Weiß, A. et al. Gas and dust in the Cloverleaf quasar at redshift 2.5. Astron. Astrophys. 409, L41–L45 (2003).

Weiß, A. et al. Atomic carbon at redshift ~2.5. Astron. Astrophys. 429, L25–L28 (2005).

Danielson, A. L. R. et al. The properties of the interstellar medium within a star-forming galaxy at z = 2.3. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 410, 1687–1702 (2011).

Bothwell, M. S. et al. ALMA observations of atomic carbon in z ~ 4 dusty star-forming galaxies. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 466, 2825–2841 (2017).

White, G. J. et al. CO and C i maps of the starburst galaxy M 82. Astron. Astrophys. 284, L23–L26 (1994).

Wilson, C. et al. Luminous infrared galaxies with the submillimeter array. I. Survey overview and the central gas to dust ratio. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 178, 189–224 (2008).

Bolatto, A. D., Wolfire, M. & Leroy, A. K. The CO-to-H2 conversion factor. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 51, 207–268 (2013).

Downes, D. & Solomon, P. M. Rotating nuclear rings and extreme starbursts in ultraluminous galaxies. Astrophys. J. 507, 615–654 (1998).

Carilli, C. L. & Walter, F. Cool gas in high-redshift galaxies. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 51, 105–161 (2013).

Bournaud, F. et al. Modeling CO emission from hydrodynamic simulations of nearby spirals, starbursting mergers, and high-redshift galaxies. Astron. Astrophys. 575, A56 (2015).

Bouche, N. et al. GalPak3D: a Bayesian parametric tool for extracting morphokinematics of galaxies from 3D data. Astrophys. J. 150, 92 (2015).

Toomre, A. On the gravitational stability of a disk of stars. Astrophys. J. 139, 1217–1238 (1964).

Wang, B. et al. Gravitational instability and disk star formation. Astrophys. J. 427, 759–769 (1994).

Binney, J. & Tremaine, S. Galactic Dynamics 2nd edn, 494–496 (Princeton Univ. Press, Princeton, 2008).

Romeo, A. B. & Wiegert, J. The effective stability parameter for two-component galactic discs: is \({Q}^{-1}\approx {Q}_{{\rm{stars}}}^{-1}+{Q}_{{\rm{gas}}}^{-1}\)? Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 416, 1191–1196 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We thank J. Baba for discussions about a gravitational instability in SMGs. This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI JP17J04449. We thank the ALMA staff and in particular the EA-ARC staff for their support. This research has made use of data from ALMA and HerMES project (http://hermes.sussex.ac.uk/). ALMA is a partnership of ESO (representing its member states), NSF (USA) and NINS (Japan), together with NRC (Canada), MOST and ASIAA (Taiwan), and KASI (South Korea), in cooperation with the Republic of Chile. The Joint ALMA Observatory is operated by ESO, AUI/NRAO and NAOJ. HerMES is a Herschel Key Programme utilizing Guaranteed Time from the SPIRE instrument team, ESAC scientists and a mission scientist. Data analysis was in part carried out on the common-use data analysis computer system at the Astronomy Data Center (ADC) of the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan.

Reviewer information

Nature thanks F. Bournaud and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.T. led the project and reduced the ALMA data. K.T. and D.I. wrote the manuscript. M.S.Y. reduced the Large Millimeter Telescope data and edited the final manuscript. Other authors contributed to the interpretation and commented on the ALMA proposal and the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

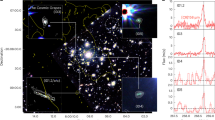

Extended Data Fig. 1 Galaxy-integrated CO (4–3), CO (1–0) and C i (2–1) spectra of AzTEC-1.

The CO (4–3) spectrum is extracted using an 0.8″-diameter aperture in the natural-weighted map cube. The C i (1–0) and C i (2–1) spectra are extracted from the peak positions in map cubes with 1.7″ × 1.1″ and 0.8″ × 0.7″ resolution, respectively. Yellow shaded regions show the velocity range v = −315 km s−1 to v = +315 km s−1, in which the velocity-integrated line fluxes are measured.

Extended Data Fig. 3 CO spectra along the kinematic major axis.

Spectra are extracted at a position angle of PA = −64°. The spatial offset x from the galactic centre is shown at the upper left of each panel. Red lines indicate the spectra of the best-fitting dynamical model produced by GalPaK3D.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Full MCMC chain for 20,000 iterations.

Red solid lines and black dashed lines indicate the median and 95% confidence interval of the last 60% of the MCMC chain.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tadaki, K., Iono, D., Yun, M.S. et al. The gravitationally unstable gas disk of a starburst galaxy 12 billion years ago. Nature 560, 613–616 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0443-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0443-1

This article is cited by

-

A giant disk galaxy two billion years after the Big Bang

Nature Astronomy (2025)

-

Molecular clouds in the Cosmic Snake normal star-forming galaxy 8 billion years ago

Nature Astronomy (2019)

Xinhang Shen

As Einstein's relativity and the Big Bang theory have been disproved, the discovery of this paper gives us a completely new idea about the age of the universe. For 12 billion years, the light of the galaxy has just reached the earth. If the universe then were at the age of 1.8 billion years and it kept expanding in a fixed acceleration from its birth to now, the distance between the earth and the galaxy should be ignorable at that time. The fact that the light has caught the earth now means that the current speed of the earth leaving the location of the galaxy at 12 billion years ago is still smaller than the speed of light. Then the speed of the earth 12 billion years ago leaving the location of the galaxy at 12 billion years ago should be much much smaller than the speed of light. Thus, how could the light needed 12 billion years to catch such a slow moving earth in an ignorable distance? It is obvious a contradiction which tells us that the distance between the earth and the galaxy at 12 billion years ago was not ignorable, but close to 12 billion light years, as the move of the earth during the 12 billion year period is ignorable compared with the distance the light has traveled. As the universe already had such a large size at that moment, the age of the universe then should not be 1.8 billion years old, but much older.

Therefore, the age of the universe now should be much older than 13.8 billion years.

urho rauhala Replied to Xinhang Shen

Good question showing a major flaw of GR based time concept, also shared by some basic mistakes of traditional QM foundations such as Planck energy constant that actually includes the variable speed C4 of the decelerating expansion of Riemann 4-radius R4. The speed of light C along the 3-D space direction orthogonal to R4 direction is closely coupled to the dynamic contraction/expansion speed C4 such that the balance of the motion and gravitational energies of total mass M in universe is continually preserved. The ticking rate of atomic clocks and other processes (such as decay rate) at small values of R4 such as 1.8B l.y was close to 1,000 times higher than today such that in terms of today's definition of 'prolonged' second the GR based age 13.8 B yrs reduces to 9.2B yrs. This explains the fast star formation process of the ALMA observed disk while also revealing some 5-10 other blunders of GR/QM based postulates, including the 'epicycle mistakes' of Dark Energy/Matter, GW etc. See the books and papers of 'Suntola Dynamic Universe' bounce (vs BB) theory since 1995, collected today at PFS web site for open view.

Also note the 'cosmic entanglement' principle of DU where the motion of any mass object, such as Earth from its birth to today, has been continually interconnected (in a 'pipeline' fashion) to the gravitational states of ALL other mass objects of universe, acting as its 'anti-matter counterpart'. The same principle applies to binary star/NS/BH pairs during millions/billions of years before their local merge event - no or little unbalanced energy left to cause the GR postulated emission of GW for detection at the global optical or 'gravitational' distance of over 100 M years. See DU explanation of the 'indirect GR proof of GW' granted Nobel award in 1990's and paving the funding of LIGO related developments, unaware of the more general digital software/hardware developments of array algebra in digital photogrammetry and geodesy since 1975. The learned lessons of both DE/DM, GW and related automated multi-ray stereo image matching and range sensing/ultra-accurate time keeping technologies of array calculus are valuable for the new technologies of cosmic mapping projects. WFIRST and Gaia/Hubble efforts are partially wasted as they were inspired by the 2011 and 2017 Nobel 'confirmations' of GR based DE and GW mistakes.