Abstract

A psychotherapeutic regimen that uses alternating bilateral sensory stimulation (ABS) has been used to treat post-traumatic stress disorder. However, the neural basis that underlies the long-lasting effect of this treatment—described as eye movement desensitization and reprocessing—has not been identified. Here we describe a neuronal pathway driven by the superior colliculus (SC) that mediates persistent attenuation of fear. We successfully induced a lasting reduction in fear in mice by pairing visual ABS with conditioned stimuli during fear extinction. Among the types of visual stimulation tested, ABS provided the strongest fear-reducing effect and yielded sustained increases in the activities of the SC and mediodorsal thalamus (MD). Optogenetic manipulation revealed that the SC–MD circuit was necessary and sufficient to prevent the return of fear. ABS suppressed the activity of fear-encoding cells and stabilized inhibitory neurotransmission in the basolateral amygdala through a feedforward inhibitory circuit from the MD. Together, these results reveal the neural circuit that underlies an effective strategy for sustainably attenuating traumatic memories.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

A permanent treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is an important goal for researchers investigating the neural mechanisms of fear1,2,3. Unfortunately, although the fear-extinction procedure triggers inhibitory learning, these changes are not persistent and patients with PTSD often suffer severe relapses of fear3. Studies using animal models have focused on direct approaches, by removing the original fear memory with chemicals that impair synapses or neurons4,5,6. However, such compounds are generally not approved for use in humans, making these approaches inappropriate for clinical applications. Consequently, current treatments for PTSD rely on basic exposure therapy, medications such as antidepressants7, and other types of psychotherapeutic support8,9. The mechanisms that underlie the effects of such treatments are largely unknown.

In this study, we sought to uncover the innate brain circuitry through which methods currently used in the clinic can produce long-lasting attenuation of fear. Several effective psychotherapeutic methods use visual stimulation, eye movements or attentional control of cognitive processes8,10. In eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR), for example, patients are instructed to recall a traumatic memory and simultaneously to orient to alternating bilateral sensory stimulation (ABS)8,11. Given that modulation of visual-attentional processes is a common component in treatment regimens for PTSD, we hypothesized that the superior colliculus (SC)—which is involved in visual-attentional processing12,13—might be responsible for the long-lasting effects14,15.

ABS-paired extinction prevents the return of fear

We first tested the effect of visual stimulation on fear responses in mice that had been trained to associate a sound (conditioned stimulus, CS) with a mild foot shock. To provide visual stimulation to freely moving mice, we placed the mice in a cylinder in which a line of LED chips was installed around the wall (Fig. 1a). Three patterns of stimulation were presented during fear extinction concurrently with the CS: (1) all of the LEDs were continuously lit (CL); (2) all of the LEDs flashed on and off synchronously (FL); and (3) the LEDs were sequentially lit and then turned off in alternating directions, which produced an effect of light moving horizontally in bilaterally alternating directions (ABS).

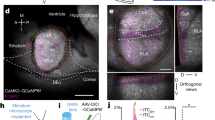

a, Experimental procedure; see Methods. Vis. stim., visual stimulation. b, Fear extinction with visual stimulation (CS, n = 9; CL + CS, n = 7; FL + CS, n = 7; ABS + CS unpaired, n = 7; ABS + CS, n = 10 mice). FC, fear conditioning. Mixed-design ANOVA for extinction: F4,35 = 12.35, P = 2.31 × 10−6 for group. One-way ANOVA during recall: F4,35 = 10.59, P = 9.96 × 10−6. c, Effects of ABS pairing on fear relapse (CS, n = 9; ABS + CS, n = 10 mice). SR, spontaneous recovery. Two-way ANOVA: F1,41 = 90.203, P = 6.516 × 10−12 for group. Asterisks above bars indicate significant fear relapse. d, Single-unit recording from the SC during fear extinction. PAG, periaqueductal grey. e, Heat map and classified SC responses (1-s bins; χ2(2) = 17.858, P = 0.0001325). f, g, Averaged positive (f) and negative (g) responses of SC neurons (1-s bins). Mann–Whitney U-test, two-sided: P = 3.492 × 10−5 for positive responses (CS, n = 33; ABS + CS, n = 62 cells), P = 0.3599 for negative responses (CS, n = 10; ABS + CS, n = 8 cells). h, i, Pearson’s correlation analyses of SC positive (h; CS, n = 9; ABS + CS, n = 8 mice) or negative (i; CS, n = 5; ABS + CS, n = 5 mice) responses during fear extinction with averaged freezing during spontaneous recovery and renewal. Mean ± s.e.m.; post hoc multiple comparison with Bonferroni correction. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. See Supplementary Table 1 for statistical details.

We found a marked reduction in freezing for mice that underwent ABS-paired fear extinction, compared to those that were exposed only to the CS (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Video 1). The reduced freezing was maintained in a recall test without ABS, suggesting that the reduction was not due simply to visually evoked motor responses, but rather was based on long-lasting modification of brain circuitry. To investigate the persistence of this fear reduction, we performed subsequent fear tests a week after fear extinction. At this point, the CS-only group showed significant spontaneous recovery and renewal of freezing, the return of fear in the extinction context and in a novel context, respectively (P = 0.001 and P = 0.0002, respectively; Bonferroni correction; see Supplementary Table 1 for detailed statistics), whereas the ABS-paired group did not show significant return of fear (Fig. 1c). Persistent fear reduction was also observed when the CS was paired with stronger foot shocks, simulating more traumatic conditions (Extended Data Fig. 1a, b).

In contrast to the ABS-paired group, the ABS-unpaired group—which was exposed to ABS at the inter-CS intervals—showed no changes in fear response (Fig. 1b, c), indicating that co-incidence is a critical factor for fear attenuation. ABS pairing during brief memory reactivation with a single CS trial also failed to induce a persistent effect (Extended Data Fig. 1c). Thus, the effects of ABS are not explained by disruption of memory reconsolidation. In addition, pairing of the CS with CL or FL did not induce long-lasting fear reduction (Fig. 1b, c), indicating that the visual stimulation protocols differed in their effectiveness.

ABS drives SC neuronal activity during extinction

We hypothesized that the induction of long-lasting fear attenuation by visual-attentional control is mediated by the SC, which is responsible for evaluating salience, regulating attention and controlling eye or body orientation12,13,16,17. To compare the abilities of the types of visual stimulation to induce neural activity in the SC, we carried out single-unit recordings in the intermediate and deep layers of the SC. Blocks of auditory (30 s, 3 kHz, continuous tone) or visual stimulation (CL, FL, or ABS) were pseudo-randomly presented to freely moving mice. ABS was the most effective stimulation protocol; it clearly activated SC neurons, whereas the other auditory and visual stimulation protocols failed to induce sustained activity (Extended Data Fig. 2a–f). These results led us to speculate that the ability of ABS to enhance SC activity could explain its behavioural effect.

Next, we initiated fear extinction and simultaneously measured neuronal activity in the SC (Fig. 1d). ABS pairing activated more SC neurons than exposure to the CS alone (Fig. 1e), and the neuronal responses were persistently increased throughout the extinction trials (Fig. 1f, Extended Data Fig. 2g–i). Notably, the magnitude of these positive responses averaged for each mouse during fear extinction were correlated with freezing behaviour during retention tests performed a week after fear extinction (Fig. 1h, Extended Data Fig. 3a–f). However, the magnitude of negative responses of inhibited neurons did not differ between groups (Fig. 1g, Extended Data Fig. 2j–l) or correlate with freezing (Fig. 1i, Extended Data Fig. 3g–j), which suggests that the effect of ABS is mediated by enhanced activation of the SC.

The SC–MD pathway mediates attenuation of fear

We next performed single-unit recording in the MD, a downstream target of the SC18,19 (Fig. 2a). The MD relays information from the SC and forms a tight loop with the prefrontal cortex and amygdala20,21,22, the main structures involved in fear extinction21,23,24. Unlike the SC, ABS pairing did not change the proportion of activated or inhibited neurons in the MD (Fig. 2b). However, consistent with the SC results, positive responses in the MD were specifically increased in the ABS-paired group (Fig. 2c, d, Extended Data Fig. 4a–j) and were correlated with fear reduction (Fig. 2e, f, Extended Data Fig. 5a–j). Thus, the effects of ABS may be mediated primarily by enhanced excitatory transmission in the SC–MD pathway.

a, Single-unit recordings from the MD during fear extinction. b, Heat map and classified MD responses (1-s bins; χ2(2) = 0.117, P = 0.943). c, d, Averaged positive (c) and negative (d) responses of MD neurons (1-s bins). Mann–Whitney U-test, two-sided: P = 2.782 × 10−6 for positive responses (CS, n = 49; ABS + CS, n = 63 cells), P = 0.9872 for negative responses (CS, n = 31; ABS + CS, n = 44 cells). e, f, Pearson’s correlation analyses of MD positive (e; CS, n = 6, ABS + CS, n = 8 mice) or negative responses (f; CS, n = 4, ABS + CS, n = 8 mice) during fear extinction with averaged freezing during spontaneous recovery and renewal. g, Viral injection and optical fibre placement for silencing the SC–MD projection. h, i, Fear extinction (h) and retention tests (i) with the SC–MD silenced (CS, eYFP, n = 9; CS, eNpHR3.0–eYFP, n = 9; ABS + CS, eYFP, n = 9; ABS + CS, eNpHR3.0–eYFP, n = 11 mice). Mixed-design ANOVA for extinction: F1,34 = 22.731, P = 3.43 × 10−5 for silencing. Mixed-design ANOVA for retention: F1,34 = 62.019, P = 3.6 × 10−9 for silencing. j, Viral injection and optical fibre placement for stimulation of SC–MD projection. k, l, Fear extinction (k) and retention tests (l) with SC–MD photostimulation (5-ms pulses at 25 Hz; YFP, n = 8; ChR2–YFP, n = 7 mice). Mixed-design ANOVA for extinction: F1,13 = 5.737, P = 0.0324 for stimulation. Mixed-design ANOVA for retention: F1,13 = 42.99, P = 1.83 × 10−5 for stimulation. Mean ± s.e.m., asterisks above bars indicate significant fear relapse. Post hoc multiple comparison with Bonferroni correction; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. See Supplementary Table 1 for statistical details.

A previous study demonstrated that burst-mode firing in the MD may have opposite effects to those of tonic-mode firing25. To assess the importance of bursts in ABS-paired extinction, we used mice with genetic knockout or MD-specific knockdown of phospholipase C-β4 (PLCβ4), which disrupts thalamic activity and enhances bursts by increasing low-threshold calcium spikes25,26. Neither Plcb4-knockout nor MD-specific knockdown mice exhibited ABS-induced fear attenuation (Extended Data Fig. 6), which suggests that a specific increase in tonic activity—but not bursting activity—in the MD is required for ABS-induced long-lasting suppression of fear.

To directly examine whether the activity of the SC–MD pathway has a causal role in fear attenuation, we used optogenetics to specifically silence this pathway during fear extinction (30-s continuous silencing; Fig. 2g, Extended Data Fig. 7b–e). SC–MD silencing blocked the effects of ABS and was associated with significant fear relapses (Fig. 2h, i; ABS+CS-eNpHR3.0-eYFP group, P = 0.0014 for spontaneous recovery, P < 0.0001 for renewal; Bonferroni correction; see Supplementary Table 1 for detailed statistics). Next, to investigate whether stimulation of this pathway is sufficient to attenuate fear responses, we paired photostimulation of the pathway with the CS during fear extinction (5-ms, 25-Hz pulses; Fig. 2j, Extended Data Fig. 7f–h). Mice subjected to SC–MD stimulation paired with CS exposure exhibited significantly reduced freezing without fear relapses (Fig. 2k, l; P = 0.0324 for group effect during extinction; P = 1.83 × 10−5 for group effect during retention tests; mixed-ANOVA; see Supplementary Table 1 for detailed statistics). Thus, increased activity in the SC–MD pathway is necessary and sufficient to prevent the return of fear.

ABS pairing induces long-lasting BLA suppression

To investigate how ABS pairing could reduce fear responses, we carried out single-unit recording in the basolateral complex of the amygdala (BLA) (Fig. 3a). In contrast to the SC and MD, ABS pairing increased the number of inhibited neurons in the BLA (Extended Data Fig. 8a–c), suggesting that ABS suppressed BLA activity. However, the averaged responses of the neurons were not changed nor correlated with freezing (Extended Data Fig. 8d–g).

a, Single-unit recordings from BLA during fear extinction. b, Representative BLA responses showing periodic pip responses (orange vertical shading, pip presentation; bars, 555-ms bins; red line, 1-s bins). c, d, Averaged trial responses (1-s bins) of fear neurons (c) and extinction neurons (d). Mann–Whitney U-test, two-sided: P = 0.006426 for fear neurons (CS, n = 34; ABS + CS, n = 42 cells). P = 0.8024 for extinction neurons (CS, n = 24; ABS + CS, n = 30 cells). e, f, Pearson’s correlation analyses of trial responses of fear cells (e; CS, n = 8; ABS + CS, n = 9 mice) and extinction cells (f; CS, n = 8; ABS + CS, n = 7 mice) with averaged freezing during spontaneous recovery and renewal. g, Experimental groups and representative mIPSC traces recorded in the BLA (naive, n = 20; conditioned (cond), n = 16; one day (1 d) CS, n = 10; one week (1 w) CS, n = 8; 1 d ABS + CS, n = 9; 1 w ABS + CS, n = 10 cells). h, i, mIPSC frequency (h) and amplitude (i) from recordings in g. One-way ANOVA: F5,67 = 28.95, P = 1.6 × 10−15 for frequency; F5,67 = 4.131, P = 0.00249 for amplitude. Post hoc multiple comparison with Holm–Sidak test; NS, not significant (P > 0.05); *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. See Supplementary Table 1 for statistical details. Data shown as mean ± s.e.m.

The neurons of the BLA comprise at least two distinct populations: those that encode the fear state and those that encode the extinction state27. Thus, we further classified recorded BLA neurons based on their auditory ‘pip’ responses27,28 (50-ms CS pips at 0.9 Hz; Extended Data Fig. 8h–n) that represent neuronal responsiveness to the CSs over extinction trials. We successfully observed periodic pip responses even in the presence of ABS (Fig. 3b) and could separately analyse overall trial responses—evoked responses maintained over 30-s trial under the effects of ABS presentation—after classification with pip responses.

The trial responses of fear cells were markedly reduced by ABS pairing (Fig. 3c). The suppression of these neurons was also correlated with fear attenuation (Fig. 3e, Extended Data Fig. 9a–f). By contrast, the activity of extinction neurons was unchanged (Fig. 3d) and did not correlate with freezing (Fig. 3f, Extended Data Fig. 9k–n). These results demonstrate that specific downregulation of fear-encoding neurons could account for the behavioural outcomes of ABS-paired extinction.

Given that ABS pairing suppresses fear cells during extinction, we tested whether these inhibitory effects persist in the BLA after fear extinction. We used ex vivo patch-clamp recording to measure miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents (mIPSCs) at various time points after fear conditioning or extinction (Fig. 3g). As previously reported29, the frequency and amplitude of mIPSCs paralleled the dynamics of fear suppression after fear conditioning and extinction (Fig. 3h, i). Notably, the frequency of mIPSCs reflected the behavioural differences between the groups; a week after extinction, the mIPSC frequency of the CS-only group had returned to the reduced pre-extinction level, whereas that of the ABS-paired group remained at a level comparable to that of naive mice (which had not undergone fear conditioning). These findings suggest that sustained inhibitory synaptic activity in the BLA contributes to the long-lasting attenuation of fear.

MD–BLA feedforward inhibition underlies ABS effects

Although the MD has been reported to be important for fear extinction and subsequent fear recovery21,25, the exact mechanism of its contribution—particularly in relation to the BLA—is unclear. To assess whether the MD–BLA projection has a causal role in this process, we applied optogenetic silencing during fear extinction (Fig. 4a). Silencing of the MD–BLA pathway completely blocked the fear-attenuating effect of ABS (Fig. 4b, c).

a, Viral injection and optical fibre placement for silencing MD–BLA projection. b, c, Fear extinction (b) and retention tests (c) with MD–BLA silencing (CS, eYFP, n = 8; CS, eNpHR3.0–eYFP, n = 9; ABS + CS, eYFP, n = 8; ABS + CS, eNpHR3.0–eYFP, n = 9 mice). Mixed-design ANOVA for extinction: F1,30 = 0.343, P = 0.56276 for silencing; F1,30 = 5.398, P = 0.02713 for the silencing × ABS interaction. Mixed-design ANOVA for retention: F1,30 = 18.334, P = 0.000175 for silencing; F1,30 = 23.208, P = 3.9 × 10−5 for silencing × ABS interaction. Asterisks above bars indicate significant fear relapse. Mean ± s.e.m., post hoc multiple comparison with Bonferroni correction. d, Viral injection and whole-cell recording (rec). In, inhibitory interneuron; Pyr, pyramidal neuron. e, Sample traces of EPSCs and IPSCs evoked by optogenetic stimulation of MD fibres. f, IPSC/EPSC peak ratios (CS, n = 11; ABS + CS, n = 12 cells; centre line, median; box limits, lower and upper quartiles; whiskers, minimum and maximum). Student’s t-test, two-sided: t(21) = −4.1723, P = 0.0004303. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. See Supplementary Table 1 for statistical details.

Although the above results showed that the MD–BLA projection is required for fear attenuation, it remained unclear how enhanced MD activity could suppress fear neurons. Moreover, the MD–BLA projection in mice was not clearly observed in a chemical tracing study30. To confirm the existence of an MD–BLA projection in mice, we injected ChR2 viruses into the MD of wild-type B6/J and Grik4-cre mice31. The latter exhibited selective expression of Cre-dependent viruses in the MD. With sufficient fluorescence excitation, we could observe axonal fibres in the BLA (Extended Data Fig. 10c–e). Photostimulation of the MD fibres induced fast monosynaptic EPSCs and delayed IPSC responses in the BLA (Extended Data Fig. 10f–j), the latencies of which were comparable to those of previously reported disynaptic feedforward inhibition32. Thus, MD neurons make functional excitatory synapses with neurons in the BLA, and they also drive feedforward inhibition onto BLA neurons.

Finally, given the existence of both excitatory and feedforward inhibitory inputs, we measured the relative strength of inhibition versus excitation a week after fear extinction (Fig. 4d). The ABS-paired group exhibited a marked increase in the IPSC/EPSC ratio (Fig. 4e, f). Overall, our findings suggest that ABS pairing enhances MD activity and thus strongly activates the MD–BLA feedforward pathway, which modifies synaptic transmission in a way that leads to lasting suppression of the amygdala.

Discussion

Existing psychotherapeutic treatments for PTSD are based heavily on empirical findings. That said, we lack scientific explanations for critical components of their effects33, and their effects have not been found consistently34,35,36. Here we describe a neural mechanism that might underlie the therapeutic effect of EMDR. We used ABS to induce long-lasting fear attenuation in mice. Owing to practical limitations, however, we could not directly monitor or control the perception or attention of mice. We focused on sensory stimulation, but not on orienting behaviours or eye movements, which are difficult to standardize in mice. However, we clearly demonstrated the role of the SC in sustained fear reduction. As the SC is widely involved in eye and body orientation37,38 and covert and overt attention13,39, these results could provide neurobiological explanations for the therapeutic effects of any procedure that potentially involves SC activation.

To summarize, we have described an animal model for psychotherapy and used it to identify an SC-activity-driven brain circuit that is distinct from the canonical extinction pathway and provides long-lasting fear attenuation. Although the SC has been shown to regulate innate fear40,41, to our knowledge it has not previously been suggested to be involved in implicitly learned emotional responses42. Various psychotherapeutic strategies involve controls of cognitive processing, which directly or indirectly modulates attentional components8,10,43. Thus, the SC might contribute to fear extinction by supporting activity in the MD and prefrontal cortex13,21 to compete with emotional activity in the amygdala44. The SC–MD–amygdala pathway described herein could be a central target for the effective treatment of PTSD.

Methods

No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample size. The subjects were randomly assigned into groups within blocks that consisted of variable number of mice with proper ages. The number of samples for each group within a block was predetermined to get balanced total sample sizes across group. Owing to the visual stimulations, the investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessment, unless stated otherwise.

Subjects

All experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Institute for Basic Science (IBS) under relevant regulations for the care and use of laboratory animals. Adult male B6 × 129 F1 mice (12–16 weeks of age) were obtained by mating the parental strains, C57BL/6J and 129s4, and used for behavioural experiments and in vivo and ex vivo electrophysiological recordings. For genetic disruption of thalamic activities, adult male Plcb4−/− and wild-type littermate mice (12–16 weeks of age) on a B6 × 129 F1 background were obtained by mating parental strain C57BL/6J (N26) Plcb4+/− and 129S4/SvJae (N39) Plcb4+/− mice45. Adult C57BL/6J naive mice and Grik4-cre mice on a B6J background were used for the in vitro feedforward inhibition test. Mice were housed with free access to food and water under a 12-h light–dark cycle.

Visual stimulation

Visual stimulation was applied to mice moving freely in a cylinder (context B; 20-cm diameter, 20-cm height) made of black acrylic and containing a horizontal line of white LEDs (chip type, 2012 size) on the wall 5 cm above the floor. To present visual ABS within the sight of the mouse, the cylinder was divided into four equal quadrants, and the moving light was applied to the wall of the quadrant towards which the mouse was facing. Each quadrant contained seven LEDs at intervals of 2 cm. The head direction of each mouse was continuously monitored during experiments, and the quadrant faced by the mouse was activated as soon as the head orientation moved between sectors. Only one quadrant was activated at a time. Once the switch was turned on, seven LEDs in a quadrant were sequentially turned on and off from one end to the other and vice versa (one round at 1 Hz). The stroke of light always started from the left side of the quadrant. LEDs in inactivated quadrants were immediately turned off. The activated sector was maintained if the mouse’s head orientation changed within the quadrant. When a mouse froze while facing between quadrants for more than 2 s, a more distant sector was activated to provide a longer light stroke within sight of the mouse. For FL stimulation, all LED lights were simultaneously flickered together (1 Hz). For CL stimulation, all LED lights were continuously turned on for 30 s. The visual stimulation patterns were automatically generated by a custom MATLAB script under the control of digital TTL input, but quadrant selection for the ABS stimulation was controlled manually by the experimenter.

Behavioural experiment

Before fear conditioning, all animals were handled and habituated to the experimental contexts for three days. On the day of conditioning, mice were placed into a standard operant chamber (17.78-cm width, 17.78-cm depth, 30.48-cm height) with white light illumination (context A) located in a sound-attenuating box (Coulbourn Instruments). Mice were conditioned with 3 presentations (at an average interval of 120 s) of auditory tones (CS: 3 kHz, continuous 30 s, 90 dB) that were co-terminated with electric foot shocks (0.3 mA or 0.7 mA, 1 s). For single-unit recordings from the BLA, discriminative fear conditioning was performed by pairing the CS+ with an unconditioned stimulus (US; five pairings; 0.3 mA, 1 s) whereas the five CS− stimuli were presented without foot shocks (CS+ and CS−: 50-ms pips repeated at 0.9 Hz, 2-ms rise and fall; pip frequency: 7.5 kHz or white-noise, counterbalanced). Except for the BLA recording experiments, all other experiments were performed with a 30-s continuous CS.

Fear extinction and retention tests took place in context B without light illumination 24 h after fear conditioning. During fear extinction, mice were presented with the 15 CSs in pseudo-random intervals from 40 to 120 s. For the BLA recordings, 5 presentations of the CS− were intermixed with the 15 CS+ presentations without pairing with the ABS. When visual stimulation was applied during fear extinction, the first CS was presented without the visual stimulation, which then was followed by 14 visual-stimulation-paired CS trials.

In the fear recall test, mice were subjected to three presentations of the CS+ and the CS− for BLA recording experiments, or three presentations of the CS in other experiments. One week after extinction training, mice were placed back into context B to measure the spontaneous recovery of fear. Two hours after the spontaneous recovery test, the same animals were tested for fear renewal in a different context (context C; right-angled triangle with 20-cm width and height made of stainless steel).

To test the effect of ABS pairing on fear retrieval and memory reconsolidation, mice were put into context B one day after fear conditioning, and a single CS (30 s, 3 kHz, continuous tone) was presented with or without ABS. One day after memory reactivation, post-reactivation long-term memory (PR-LTM) was measured using three presentations of the CS in the same context.

Freezing behaviours (lack of movement except for respiration) were manually counted by colleagues blinded to experimental groups, except for the fear extinction session, during which visual stimulation was visible to researchers. The validity of manual scoring during fear extinction was confirmed using trial-by-trial correlation analysis with pooled CS and ABS + CS group data, in which the manually scored freezing level showed a significant positive correlation with automatic data (r > 0.7, P < 1 × 10−10).

Virus-mediated gene expression and knockdown

For optogenetic stimulation of axonal fibres projecting from the SC, adeno-associated viral vectors (AAV, serotype 9) were obtained from the Penn Vector Core at the University of Pennsylvania. AAV9-EF1α-ChR2-YFP was injected into the right SC (AP −3.4 mm, ML −1.1 mm, DV −2.2 mm), and AAV9-EF1α-YFP was used as a control. For optogenetic silencing of the SC–MD projection, viral vectors were obtained from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Vector Core (UNC). AAV5-hSyn-eNpHR3.0-eYFP was bilaterally injected into the SC, and AAV5-hSyn-eYFP was used as a control. For optogenetic silencing of the MD–BLA projection, AAV5-CaMKIIα-eNpHR3.0-eYFP (UNC) was bilaterally injected into the MD, and AAV5-CaMKIIα-eYFP was used as a control. For feedforward inhibition recordings, AAV5-CaMKIIα-ChR2-eYFP or AAV5-EF1α-DIO-ChR2-eYFP (UNC) was bilaterally injected into the MD. For knocking down of PLCβ4, lentiviral vectors expressing a small hairpin RNA (shRNA) targeting Plcb4 mRNA were created as previously described25. Mice were given bilateral injections of either Plcb4-specific (shPlcb4) or non-target control shRNA into the MD (AP −1.3 mm, ML ±0.3 mm, DV −3.2 mm from the brain surface).

For viral injection, mice were anaesthetized with isoflurane (5%) in an induction chamber and injected with either 2% avertin (tribromoethyl alcohol/tertiary amyl alcohol; Aldrich) or a mixture of ketamine (120 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg). Viruses were injected while mice were fixed in a stereotaxic frame (David Kopf Instruments) at a rate of 0.1 μl/min using a Hamilton syringe connected to a microinjection pump (sp100i; World Precision Instruments).

To verify the knockdown of Plcb4 expression in the MD, immunohistochemistry was performed as previously described25. In brief, mice were anaesthetized and transcardially perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Brains were post-fixed with the same solution, and then sectioned using a vibratome into coronal sections. Every sixth section in the series throughout the entire MD was used. To evaluate changes in PLCβ4-positive neuron morphology and PLCβ4 expression resulting from injection of shPlcb4 into the MD, sliced brain sections were stained by incubation with rabbit antibodies to PLCβ4 (1:100, Santa Cruz Biochemicals) and Cy3-conjugated secondary antisera (1:500, Jackson Immunolabs) using free-floating methods. Sections were mounted in Vectashield mounting medium with diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Vector Laboratories). Images were captured and analysed using a Nikon DS-Ri1 digital camera and NIS-Elements AR 4.2 microscopic digital camera software.

Optogenetic experiments

For optogenetic stimulation of the SC–MD projection, fibre-optic cannulas (100-μm core diameter, 0.22 NA, diffuser layer, Doric lenses) were implanted so that the tip was right above the MD (AP −1.25 mm, ML −0.5 mm, DV −2.8 mm) to stimulate axonal projections from the SC. Laser stimuli (473-nm DPSS laser, CrystaLaser) consisted of 5-ms pulses at 25 Hz; stimulation of the SC at this frequency has been shown to modulate orienting behaviour in mice16. The first trial in the extinction training was CS exposure without laser stimulation, which then was followed by 14 laser-stimulus-paired CS trials. Excitation of MD neurons by photostimulation of the SC fibres was confirmed in a slice patch recording with 5-ms blue-laser pulses at 25 Hz.

For optogenetic silencing of the SC–MD pathway, fibre-optic cannulas (200-μm core diameter, 0.39 NA, Thorlabs) were bilaterally implanted over the MD (AP −1.25 mm, ML ±0.5 mm, DV −2.8 mm, at 20° angle). For optogenetic silencing of the MD–BLA pathway, fibre-optic cannulas (200-μm core diameter, 0.39 NA, Thorlabs) were bilaterally implanted over the BLA (AP −1.5 mm, ML ±3.1 mm, DV −4.0 mm). Laser illumination (561-nm DPSS laser, CNI) was applied continuously during the CS presentation from the second trial of the extinction.

Laser power density was adjusted to around 150 mW/mm2 at the tip of the optical fibres (PM100D, Thorlabs) before starting experiments. Zirconia sleeves were tightly wrapped with black tape or covered to minimize leakage of the light during optogenetic experiments.

Single-unit recording

Data acquisition and spike sorting

To record responses to sensory stimulation in the SC, extracellular signals were chronically recorded with 64-channel silicon probes (A4x16-Poly2-5mm-23 s-200-177, Neuronexus) attached to a custom-built microdrive (centre coordinates for the intermediate and deep layer of the SC: AP −3.45 mm, ML −1 mm, DV 2.2 mm). In each daily recording session, mice (without fear conditioning) were placed in cylindrical context B, and four types of sensory stimulation were presented while mice were moving freely in the context: (1) auditory tone (AUD: 3 kHz, continuous 30 s, 90 dB); (2) CL; (3) FL; and (4) ABS. Recording sessions consisted of four blocks in a pseudo-random, counterbalanced order, and each block consisted of one type of sensory stimulation with ten repetitions (30 s each). After each recording session, silicon probes were lowered by around 100 µm per day. To minimize habituation to sensory stimulation, a maximum of two sessions were recorded for each mouse.

Single-unit activity was recorded during fear extinction using 64-channel silicon probes (for SC recording; Neuronexus) or commercial microdrives (Harlan 4 drive, Neurlaynx) consisting of four individually movable tetrodes (for MD recording), or an array of 8 or 16 tetrodes with or without a custom microdrive (for SC, MD and BLA recording). The centre coordinates for the intermediate and deep layers of the SC were: AP –3.45 mm, ML –1 mm, DV 2.2 mm; for the MD: AP –1.3 mm, ML –0.3 mm, DV 3.2 mm; and for the BLA: AP –1.5 mm, ML –3.1 mm, DV –4.7 mm. Tetrode impedance was measured and adjusted to around 200 kΩ at 1 kHz (IMP-2, Bak Electronics). Behavioural protocols were the same as for experimental procedures without single-unit recording. The SC and MD recordings were performed with continuous auditory CS, and BLA recordings were performed with 0.9-Hz, 50-ms auditory pips (see ‘Behavioural experiments’ above).

Signals were filtered at 300–6,000 Hz and digitized at 32 kHz using a Digital Lynx acquisition system (for MD recording with Harlan 4 drive; Neuralynx) or sampled at 24 kHz and filtered at 300–5,000 Hz using an RZ2 processor system (for SC, MD and BLA recording; Tucker-Davis Technology). Upon completion of all experiments, mice were anaesthetized with 2% avertin, and an electrical lesion was labelled by passing anodal current (20 µA for 10 s). The placement of electrode tips was histologically verified by cresyl violet staining of a series of coronal sections (30-µm thickness).

Spikes were first sorted by an unsupervised clustering method using KlustaKwik46 on the basis of waveform features such as peak, energy, valley and the first two principal components. The sorted spikes were then manually corrected with MClust (AD Redish, http://redishlab.neuroscience.umn.edu/MClust/MClust.html) or custom-built Python software. For manual correction, the isolation distance and L-ratio were calculated to confirm clear isolation of the unit47. Only clusters with clear refractory period (>1 ms) were further analysed. Burst spikes triggered by low-threshold calcium spike (LTS) were isolated, as abnormally increased MD bursts have a distinct role in fear extinction25. In brief, an LTS burst was defined as a series of spikes with a first inter-spike interval (ISI) of ≤4 ms and progressive prolongation of successive ISIs, along with silent periods of ≥100 ms before and after burst firing. Only MD spikes in tonic mode were used for further analysis, as the frequency of burst events was very low and did not differ between groups (during tone: CS only, 0.016 ± 0.0023; ABS-paired CS, 0.022 ± 0.0033; during inter-tone: CS only, 0.018 ± 0.0024; ABS-paired CS, 0.023 ± 0.0031).

Data analysis

To analyse neuronal activity in the SC and MD during 30-s trials, z-scored peristimulus time histograms (PSTHs) were calculated for each individual neuron, averaged over 10 trials for SC sensory responses or 14 CS trials for fear extinction, with or without ABS (from the second extinction trial). Spikes were divided into 500-ms bins for visualizing individual cell responses or divided into 1-s bins for comparing responses between groups. A z-score was calculated for each bin relative to the 10-s prestimulus activity by subtracting average firing rate during baseline and by dividing the difference by the baseline standard deviation. Cells were considered responsive if their maximum absolute z-score exceeded 1.96 (P < 0.05, two-tailed) within 5 s of stimulus onset. For SC sensory response recordings, only positive responses were presented in the classification result because negative responses were barely observed (1/109 neurons during ABS presentation, and 0/109 neurons during other sensory stimuli). To compare PSTHs between groups, the mean z-score was calculated for each neuron by averaging z-scored PSTHs during the response peak (5 s for SC responses, 10 s for MD and BLA trial responses). Response heat maps were generated from z-scored PSTHs of neurons sorted by their mean z-score during the peak. Three-dimensional representations of responses over trials were made by calculating z-scored PSTHs averaged over neurons for each trial. For correlation analysis with behavioural data, mean z-score values of neurons were averaged for each subject. Mice without any corresponding responsive neurons were excluded from the correlation analysis.

BLA neurons were classified on the basis of pip responses during the first extinction trial (high fear state) and the last extinction trial (low fear state)27,28,48. Responses were divided into 20-ms bins, and z-scored PSTHs were calculated for each bin related to 500-ms prestimulus activity. Cells were considered responsive if their maximum z-score exceeded 1.96 (P < 0.05, two-tailed) within 40 ms of stimulus onset. Only pip-excited neurons were considered for analysis. The initial-trial pip-responsive neurons were classified as fear neurons if they were not last-trial pip-responsive and as resistant neurons if they were last-trial pip-responsive. Neurons with significant last-trial pip responses without significant initial-trial pip responses were classified as extinction neurons. To minimize the effect of ABS on classification, first pip responses in each trial were not considered. To compare pip responses, mean z-scores within 40 ms of pip onset were calculated. Trial responses of BLA neurons were analysed using the same methods used in the SC and MD analyses. Electrophysiological data were analysed using R and python scripts.

Whole-cell recording

Mice were anaesthetized with halothane and decapitated. Brains were rapidly removed and placed into oxygenated ice-cold slicing solution containing (in mM) 2.5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 2 MgSO4, 26 NaHCO3, 1.25 KH2PO4, 25.2 sucrose, 10 glucose (290–300 mOsm). Coronal brain slices of 300 µm were prepared using a vibratome (Leica VT 1200S). Slices were incubated at 37 °C in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) containing (in mM) 130 NaCl, 3.5 KCl, 1 CaCl2, 3 MgCl2, 24 NaHCO3, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 10 glucose for 1 h before recordings. Slices were transferred to a recording chamber that was continuously perfused with extracellular solution (310–320 mOsm) containing (in mM) 130 NaCl, 3.5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1.3 MgCl2, 24 NaHCO3, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 10 glucose. All ACSF solutions were oxygenated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 mixed gas. Whole-cell recordings were carried out with a recording pipette (4–7 MΩ) filled with an intracellular solution containing (in mM) 122.5 Cs-gluconate, 17.5 CsCl, 2 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 0.5 EGTA, 4 MgATP, 0.3 Na3GTP, and 5 QX-314 (pH adjusted to 7.2 with CsOH). Signals were digitized using Digidata 1440 or 1550 and amplified using a Multiclamp 700B amplifier (Molecular Devices) controlled by a Multi-Clamp Commander and pClamp 10 acquisition software (Molecular Devices).

Whole-cell slice patch-clamp recordings of mIPSCs were carried out on pyramidal neurons in the BLA, voltage clamped at 10 mV. GABA-A (γ-aminobutyric acid-A) receptor-mediated mIPSCs were isolated in the presence of 20 µM 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX; Tocris), 50 µM d-2-amino-5-phosphonovalerate (d-AP5; Tocris) and 1 µM tetrodotoxin (TTX; Tocris). The amplitude and frequency of mIPSCs were analysed using MiniAnalysis (Synaptosoft) and were shown to decrease with fear conditioning and increase following fear extinction29. Access resistance (Ra, 10–40 MΩ) was continuously monitored. Data were discarded if Ra varied by >20% during recording. Only neurons in the BLA with membrane capacitance ranging from 100 to 150 pF were considered for recordings.

Mice expressing ChR2 in the superior colliculus were killed after behavioural experiments, and whole-cell recordings were carried out using potassium-based internal solution containing (in mM) 122.5 K-gluconate, 17.5 KCl, 2 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 10 BAPTA, 0.5 EGTA, 4 MgATP, and 0.3 Na3GTP (pH adjusted to 7.2 with KOH). Action potential firings were measured in MD neurons using an optopatcher system (A-M Systems) by activating the axon terminals of afferent fibres originating from the SC.

For the feedforward inhibition test, pyramidal neurons in the BLA were recorded using caesium-based internal solution containing (in mM) 130 Cs-gluconate, 3 CsCl, 2 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 10 EGTA, 4 MgATP, 0.3 Na3GTP and 5 QX-314 (pH adjusted to 7.2 with CsOH). EPSCs and IPSCs were recorded at −60 mV and +10 mV, respectively, with 1- or 2-ms laser pulses at 10-s interval with 0.5–5 mW power (473-nm DPSS laser, CrystaLaser). For ex vivo recording to compare the ratio of feedforward inhibition over monosynaptic excitation, the existence of EPSCs and IPSCs was first tested with laser intensity up to 5 mW power. Then, recordings were performed with 1-ms laser pulses with power around 1 mW. Only neurons exhibiting both EPSCs and IPSCs were recorded and analysed.

Statistics

All statistical analyses were carried out using R. The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to confirm normality of behavioural data. ANOVAs were performed using a linear mixed effects model (nlme package). Post hoc multiple comparisons were conducted using the Bonferroni correction (emmeans and multcomp packages). For comparisons of single-unit responses, the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U-test was used. Correlations between neuronal activity and freezing were calculated using Pearson’s correlation test. Two-tailed tests were used for all analyses.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Code availability

All custom scripts used in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Data availability

All data used in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Quirk, G. J. et al. Erasing fear memories with extinction training. J. Neurosci. 30, 14993–14997 (2010).

Sandkühler, J. & Lee, J. How to erase memory traces of pain and fear. Trends Neurosci. 36, 343–352 (2013).

Goode, T. D. & Maren, S. Animal models of fear relapse. ILAR J. 55, 246–258 (2014).

Nader, K., Schafe, G. E. & Le Doux, J. E. Fear memories require protein synthesis in the amygdala for reconsolidation after retrieval. Nature 406, 722–726 (2000).

Shema, R., Sacktor, T. C. & Dudai, Y. Rapid erasure of long-term memory associations in the cortex by an inhibitor of PKMζ. Science 317, 951–953 (2007).

Han, J.-H. et al. Selective erasure of a fear memory. Science 323, 1492–1496 (2009).

Karpova, N. N. et al. Fear erasure in mice requires synergy between antidepressant drugs and extinction training. Science 334, 1731–1734 (2011).

Shapiro, F. Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR): Basic Principles, Protocols, and Procedures 2nd edn (Guilford, New York, 2001).

Resick, P. A. & Schnicke, M. K. Cognitive processing therapy for sexual assault victims. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 60, 748–756 (1992).

Badura-Brack, A. S. et al. Effect of attention training on attention bias variability and PTSD symptoms: randomized controlled trials in Israeli and U.S. combat veterans. Am. J. Psychiatry 172, 1233–1241 (2015).

Wurtz, H. et al. Preventing long-lasting fear recovery using bilateral alternating sensory stimulation: a translational study. Neuroscience 321, 222–235 (2016).

Sommer, M. A. & Wurtz, R. H. Brain circuits for the internal monitoring of movements. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 31, 317–338 (2008).

Krauzlis, R. J., Lovejoy, L. P. & Zénon, A. Superior colliculus and visual spatial attention. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 36, 165–182 (2013).

Wilson, S. A., Becker, L. A. & Tinker, R. H. Fifteen-month follow-up of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder and psychological trauma. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 65, 1047–1056 (1997).

Edmond, T. & Rubin, A. Assessing the long-term effects of EMDR: results from an 18-month follow-up study with adult female survivors of CSA. J. Child Sex. Abuse 13, 69–86 (2004).

Stubblefield, E. A., Costabile, J. D. & Felsen, G. Optogenetic investigation of the role of the superior colliculus in orienting movements. Behav. Brain Res. 255, 55–63 (2013).

White, B. J., Kan, J. Y., Levy, R., Itti, L. & Munoz, D. P. Superior colliculus encodes visual saliency before the primary visual cortex. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 9451–9456 (2017).

Sommer, M. A. & Wurtz, R. H. What the brain stem tells the frontal cortex. I. Oculomotor signals sent from superior colliculus to frontal eye field via mediodorsal thalamus. J. Neurophysiol. 91, 1381–1402 (2004).

Sommer, M. A. & Wurtz, R. H. Influence of the thalamus on spatial visual processing in frontal cortex. Nature 444, 374–377 (2006).

Oyoshi, T., Nishijo, H., Asakura, T., Takamura, Y. & Ono, T. Emotional and behavioral correlates of mediodorsal thalamic neurons during associative learning in rats. J. Neurosci. 16, 5812–5829 (1996).

Herry, C. & Garcia, R. Prefrontal cortex long-term potentiation, but not long-term depression, is associated with the maintenance of extinction of learned fear in mice. J. Neurosci. 22, 577–583 (2002).

Lee, S. & Shin, H.-S. The role of mediodorsal thalamic nucleus in fear extinction. J. Anal. Sci. Technol. 7, 13 (2016).

Milad, M. R. & Quirk, G. J. Neurons in medial prefrontal cortex signal memory for fear extinction. Nature 420, 70–74 (2002).

Amano, T., Unal, C. T. & Paré, D. Synaptic correlates of fear extinction in the amygdala. Nat. Neurosci. 13, 489–494 (2010).

Lee, S. et al. Bidirectional modulation of fear extinction by mediodorsal thalamic firing in mice. Nat. Neurosci. 15, 308–314 (2011).

Cheong, E. et al. Tuning thalamic firing modes via simultaneous modulation of T- and L-type Ca2+ channels controls pain sensory gating in the thalamus. J. Neurosci. 28, 13331–13340 (2008).

Herry, C. et al. Switching on and off fear by distinct neuronal circuits. Nature 454, 600–606 (2008).

Senn, V. et al. Long-range connectivity defines behavioral specificity of amygdala neurons. Neuron 81, 428–437 (2014).

Lin, H.-C., Mao, S.-C. & Gean, P.-W. Block of γ-aminobutyric acid-A receptor insertion in the amygdala impairs extinction of conditioned fear. Biol. Psychiatry 66, 665–673 (2009).

Mátyás, F., Lee, J., Shin, H.-S. & Acsády, L. The fear circuit of the mouse forebrain: connections between the mediodorsal thalamus, frontal cortices and basolateral amygdala. Eur. J. Neurosci. 39, 1810–1823 (2014).

Nakazawa, K. et al. Requirement for hippocampal CA3 NMDA receptors in associative memory recall. Science 297, 211–218 (2002).

Delevich, K., Tucciarone, J., Huang, Z. J. & Li, B. The mediodorsal thalamus drives feedforward inhibition in the anterior cingulate cortex via parvalbumin interneurons. J. Neurosci. 35, 5743–5753 (2015).

Lee, C. W. & Cuijpers, P. A meta-analysis of the contribution of eye movements in processing emotional memories. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 44, 231–239 (2013).

Mello, P. G., Silva, G. R., Donat, J. C. & Kristensen, C. H. An update on the efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy, cognitive therapy, and exposure therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. Int. J. Psychiatry Med. 46, 339–357 (2013).

Chen, L., Zhang, G., Hu, M. & Liang, X. Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing versus cognitive-behavioral therapy for adult posttraumatic stress disorder: systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 203, 443–451 (2015).

Haagen, J. F. G., Smid, G. E., Knipscheer, J. W. & Kleber, R. J. The efficacy of recommended treatments for veterans with PTSD: a metaregression analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 40, 184–194 (2015).

McHaffie, J. G. & Stein, B. E. Eye movements evoked by electrical stimulation in the superior colliculus of rats and hamsters. Brain Res. 247, 243–253 (1982).

Gandhi, N. J. & Katnani, H. A. Motor functions of the superior colliculus. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 34, 205–231 (2011).

Ignashchenkova, A., Dicke, P. W., Haarmeier, T. & Thier, P. Neuron-specific contribution of the superior colliculus to overt and covert shifts of attention. Nat. Neurosci. 7, 56–64 (2004).

Wei, P. et al. Processing of visually evoked innate fear by a non-canonical thalamic pathway. Nat. Commun. 6, 6756 (2015).

Evans, D. A. et al. A synaptic threshold mechanism for computing escape decisions. Nature 558, 590–594 (2018).

Cohen, J. D. & Castro-Alamancos, M. A. Early sensory pathways for detection of fearful conditioned stimuli: tectal and thalamic relays. J. Neurosci. 27, 7762–7776 (2007).

Kaczkurkin, A. N. & Foa, E. B. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders: an update on the empirical evidence. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 17, 337–346 (2015).

LeDoux, J. E. Emotion circuits in the brain. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 23, 155–184 (2000).

Kim, D. et al. Phospholipase C isozymes selectively couple to specific neurotransmitter receptors. Nature 389, 290–293 (1997).

Kadir, S. N., Goodman, D. F. M. & Harris, K. D. High-dimensional cluster analysis with the masked EM algorithm. Neural Comput. 26, 2379–2394 (2014).

Schmitzer-Torbert, N., Jackson, J., Henze, D., Harris, K. & Redish, A. D. Quantitative measures of cluster quality for use in extracellular recordings. Neuroscience 131, 1–11 (2005).

An, B., Hong, I. & Choi, S. Long-term neural correlates of reversible fear learning in the lateral amygdala. J. Neurosci. 32, 16845–16856 (2012).

Acknowledgements

We thank Y.-S. Kim for providing the PLCß4 knockdown virus, G. Buzsáki for advising us on silicon probe recording in freely moving mice, and J. J. Shin for discussions on slice recordings. This work was supported by IBS grant IBS-R001-D1.

Reviewer information

Nature thanks J. Johansen, G. Quirk and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J. Baek, S.L. and H.-S.S. designed the experiments and wrote the manuscript. J. Baek performed in vitro and in vivo electrophysiology and optogenetic experiments. S.L. performed behavioural experiments. S.-W.K. contributed to genetic studies. M.K. and Y.Y. contributed to histological work. T.C. performed in vitro electrophysiology. K.K.K. and J. Byun contributed to in vitro electrophysiology analysis. J. Byun performed blinded counting. S.J.K. aided in the interpretation of data and contributed to editing the manuscript. J.J. and H.-S.S. supervised the project and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Fig. 1 Effect of ABS pairing on fear extinction of strong fear memory and effect on memory reactivation and reconsolidation.

a, One day after fear conditioning (0.7 mA foot shock), visual stimulation was presented during fear extinction (n = 7 mice for each group). Mixed-design ANOVA for extinction: F4,30 = 78.62, P = 1.85 × 10−15 for group effect. One-way ANOVA for recall test: F4,30 = 53.95, P = 2.81 × 10−13. b, Effects of ABS pairing on fear relapse (n = 7 mice for each group). Two-way ANOVA: F1,36 = 138.521, P = 6.73 × 10−14 for group effect. Post hoc multiple comparison with Bonferroni correction; ***P < 0.001. Asterisks above bars indicate significant difference in comparison to recall. c, Effects of ABS pairing during memory reactivation (CS, n = 8; ABS + CS, n = 8 mice). Student’s t-test, two-sided: t(14) = −3.9058, P = 0.001584 for memory reactivation; t(14) = 0.2411, P = 0.813 for PR-LTM; **P < 0.01. Data shown as mean ± s.e.m. See Supplementary Table 1 for statistical details.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Single-unit recording of SC.

a, Coronal sections showing the positions of the silicon probes (left) and tetrodes (right). SGS, stratum griseum superficiale; SGI, stratum griseum intermediale; SGP, stratum griseum profundum. b, Schematic of 64-channel silicon probes used for SC recordings. c, Example waveforms of recorded neurons from a single shank. d, Probe tracks (left) and tetrode tip locations (right). e, Example single-unit responses of the SC to sensory stimulation (500-ms bins; pie charts, n = 109 cells). Sensory stimulation blocks were pseudo-randomly presented. f, Averaged SC responses during 5 s after stimulus onset (n = 109 cells). Mixed-design ANOVA: F3,324 = 15.4, P = 2.17 × 10−19 for stimulation effect. g, h, Positive responses of SC neurons from CS group (g; n = 33 cells) and ABS + CS group (h; n = 62 cells) during fear extinction. i, Averaged positive responses across extinction trials (early, second-to-fifth trials; mid, sixth-to-tenth trials; late, eleventh-to-fifteenth trials; samples from g, h). Mixed-design ANOVA: F1,93 = 7.621, P = 0.00695 for group effect. j, k, Negative responses of SC neurons from CS group (j; n = 10 cells) and ABS + CS group (k; n = 8 cells) during fear extinction. l, Averaged negative responses across extinction trials (samples from j, k). Mixed-design ANOVA: F1,16 = 0.71, P = 0.412 for group effect. Mean ± s.e.m.; post hoc multiple comparison with Bonferroni correction; *P < 0.05. See Supplementary Table 1 for statistical details.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Freezing behaviour and correlation with SC activity during fear extinction.

a, b, Fear extinction (a) and subsequent retention tests (b) with SC single-unit recordings (CS, n = 10; ABS + CS, n = 8 mice). Mixed-design ANOVA for extinction: F1,16 = 29.73, P = 5.32 × 10−5 for group effect. Mixed-design ANOVA for retention tests: F1,16 = 32.65, P = 3.2 × 10−5 for group effect. Mean ± s.e.m.; post hoc multiple comparison with Bonferroni correction; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Asterisks above bars indicate significant difference in comparison to recall. c–f, Pearson’s correlation analyses of SC positive responses (CS, n = 9; ABS + CS, n = 8 mice) during fear extinction with freezing during late extinction trials (c; a block of the last three extinction trials), recall test (d), spontaneous recovery test (e) or renewal test (f). g–j, Pearson’s correlation analyses of SC negative responses (CS, n = 5; ABS + CS, n = 5 mice) during fear extinction with freezing during late extinction trials (g), recall test (h), spontaneous recovery test (i) or renewal test (j). See Supplementary Table 1 for statistical details.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Single-unit recording of MD.

a, Coronal section showing the position of the recording sites (red arrow). HB, habenular nucleus; PVT, paraventricular thalamic nucleus. b, c, An example spike sorting result from a single tetrode. b, Example feature plot showing clusters of candidate spikes; c, average waveforms of isolated units from the tetrode. d, Tetrode tip locations in MD. e, f, Positive responses of MD neurons in CS group (e; n = 49 cells) and ABS + CS group (f; n = 63 cells) g, Averaged positive responses across extinction trials (early, second-to-fifth trials; mid, sixth-to-tenth trials; late, eleventh-to-fifteenth trials; samples from e, f). Mixed-design ANOVA: F1,110 = 17.83, P = 4.99 × 10−5 for group effect. h, i, Negative responses of MD neurons in CS group (h; n = 31 cells) and ABS + CS group (i; n = 44 cells) during fear extinction. j, Averaged negative responses of the MD across extinction trials (samples from h, i). Mixed-design ANOVA: F1,73 = 1.762, P = 0.188 for group effect. Mean ± s.e.m.; post hoc multiple comparison with Bonferroni correction; ***P < 0.001. See Supplementary Table 1 for statistical details.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Freezing behaviour and correlation with MD activity during fear extinction.

a, b, Fear extinction (a) and subsequent retention tests (b) with MD single-unit recordings (CS, n = 6; ABS + CS, n = 8 mice). Mixed-design ANOVA for extinction: F1,12 = 13.85, P = 0.000292 for group effect. Mixed-design ANOVA for retention tests: F1,12 = 33.1, P = 9.11 × 10−5 for group effect. Mean ± s.e.m.; post hoc multiple comparison with Bonferroni correction; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. c–f, Pearson’s correlation analyses of MD positive responses (CS, n = 6; ABS + CS, n = 8 mice) during fear extinction with freezing during late extinction trials (c, a block of the last three extinction trials), recall test (d), spontaneous recovery test (e) or renewal test (f). g–j, Pearson’s correlation analyses of MD negative responses (CS, n = 4; ABS + CS, n = 8 mice) during fear extinction with freezing during late extinction trials (g), recall test (h), spontaneous recovery test (i) or renewal test (j). See Supplementary Table 1 for statistical details.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Plcb4 deletion disturbing MD activity blocks the effects of ABS paired extinction.

a, Effects of the Plcb4 knockout (KO) on ABS paired extinction (wild-type (WT) CS, n = 5; WT ABS + CS, n = 5; KO CS n = 5; KO ABS + CS n = 7 mice). Mixed-design ANOVA for fear extinction: F3,18 = 57.56, P = 2.01 × 10−9 for group effect. One-way ANOVA for recall test: F3,18 = 35.24, P = 9.6 × 10−8. b, Effects of Plcb4 knockdown in MD on ABS paired extinction (shControl CS, n = 4; shControl ABS + CS, n = 7; shPlcb4 CS, n = 4; shPlcb4 ABS + CS, n = 5 mice). Mixed-design ANOVA for fear extinction: F3,16 = 19.25, P = 1.47 × 10−5 for group effect. One-way ANOVA for recall test: F3,16 = 26.18, P = 2.07 × 10−6. Mean ± s.e.m; ***P < 0.001. See Supplementary Table 1 for statistical details. c–j, Knockdown of Plcb4 in the MD by injection of shRNA lentiviral vector. Double fluorescence labelling of PLCβ4 expression with DAPI counterstain in the MD of shControl-injected mice (c–f) and shPlcb4-injected mice (g–j). Histology was confirmed for all mice in b after behavioural experiments. d–f, h–j, Higher magnification images corresponding to the rectangles in c, g, respectively. Scale bars, 1,000 μm (c, g); 100 μm (d–f, h–j).

Extended Data Fig. 7 Verification of viral expression and functional connectivity of the SC–MD pathway.

a, Retrograde tracer CTB (green) was injected into the MD. Only 6.12% (37/600) of CTB-positive neurons were GABA-positive and only 4.38% (37/844) of GABA-positive neurons were CTB-positive. Experiments were repeated with three mice (two slices per mouse) with similar results, and combined cell numbers are presented. White arrow indicates a CTB-positive GABAergic neuron in the SC. Scale bar, 20 μm. b, Illustration of viral injections in SC and fibre placement in MD. c, Coronal section showing a neuron expressing eNpHR3.0–eYFP in SC. Viral expression was confirmed in 20 mice after behavioural experiments (Fig. 2g–i). d, Coronal section showing fibres expressing eNpHR3.0–eYFP in MD. Viral expression was confirmed in 20 mice after behavioural experiments (Fig. 2g–i). e, Optical fibre placements for SC–MD silencing experiments. f, ChR2–YFP virus injection in SC and slicing position for whole-cell recording of MD neurons (blue dashed line). g, A sample trace of action potentials recorded from MD neurons in slice culture in response to ChR2 stimulation of the SC–MD pathway. h, Optical fibre placements for SC–MD photostimulation experiments.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Single-unit recording of BLA neurons and their classification.

a, Coronal section (left) and illustration (right) showing the position of the recording site. LA, lateral nucleus of the amygdala; BA, basal nucleus of the amygdala. b, An example spike sorting showing clusters of candidate spikes (left) and average waveforms of four isolated units (right) from a single tetrode. c, Heat map and classified BLA responses during extinction trials (1-s bins; χ2(2) = 16.204, P = 0.0003029 (CS, n = 190; ABS + CS n = 227 cells). d, e, Average positive responses (d; CS, n = 67; ABS + CS, n = 63 cells) and negative responses (e; CS, n = 36; ABS + CS, n = 84 cells) in the BLA during fear extinction (1-s bins). Mann–Whitney U-test, two-sided: P = 0.3736 for positive responses; P = 0.296 for negative responses. f, g, Pearson’s correlation analysis of BLA positive responses (f; CS, n = 8, ABS + CS, n = 6 mice) or negative responses (g; CS, n = 8, ABS + CS, n = 9 mice) during fear extinction with average freezing level during spontaneous recovery and renewal. h, Proportions of the classified BLA responses (χ2(3) = 2.0536, P = 0.5613). i–k, Averaged pip responses (20-ms bins) of classified fear cells (i; CS, n = 34; ABS + CS, n = 42 cells), resistant cells (j; CS, n = 21; ABS + CS, n = 16 cells) and extinction cells (k; CS, n = 24; ABS + CS, n = 30 cells) during the first extinction trial (left) and the last extinction trial (right). l–n, Time course of averaged pip responses (left) and trial responses (right) of fear cells (l; samples from i), resistant cells (m; samples from j) and extinction cells (n; samples from k) during fear extinction (early, second-to-fifth trials; mid, sixth-to-tenth trials; late, eleventh-to-fifteenth trials). Mixed-design ANOVA for pip responses: F1,74 = 0.513, P = 0.476 for group effect of fear cells; F1,35 = 2.859, P = 0.0998 for group effect of resistant cells; F1,52 = 0.345, P = 0.559 for group effect of extinction cells. Mixed-design ANOVA for trial responses: F1,74 = 4.775, P = 0.032 for group effect of fear cells; F1,35 = 4.846, P = 0.0344 for group effect of resistant cells; F1,52 = 0.638, P = 0.428 for group effect of extinction cells. Mean ± s.e.m.; post hoc multiple comparison with Bonferroni correction. See Supplementary Table 1 for statistical details.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Freezing behaviour and correlation with BLA activity during fear extinction.

a, b, Fear extinction (a) and subsequent retention tests (b) with BLA single-unit recordings (CS, n = 8; ABS + CS, n = 9 mice). Mixed-design ANOVA for extinction: F1,15 = 19.46, P = 0.000505 for group effect. Mixed-design ANOVA for retention tests: F1,15 = 27.29, P = 0.000103 for group effect. Mean ± s.e.m.; post hoc multiple comparison with Bonferroni correction; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. c–f, Pearson’s correlation analyses of fear-cell trial responses (CS, n = 8; ABS + CS, n = 9 mice) with freezing during late extinction trials (c; a block of the last three extinction trials), recall test (d), spontaneous recovery test (e) or renewal test (f). g–j, Pearson’s correlation analyses of resistant-cell trial responses (CS, n = 7; ABS + CS, n = 7 mice) with freezing during late extinction trials (g), recall test (h), spontaneous recovery test (i) or renewal test (j). k–n, Pearson’s correlation analyses of extinction-cell trial responses (CS, n = 8; ABS + CS, n = 7 mice) with freezing during late extinction trials (k), recall test (l), spontaneous recovery test (m) or renewal test (n). See Supplementary Table 1 for statistical details.

Extended Data Fig. 10 The MD drives feedforward inhibition in the BLA.

a, Fear extinction training for ex vivo mIPSC recordings in the BLA (conditioned (cond), n = 3; 1 d CS, n = 2; 1 d ABS + CS, n = 3; 7 d CS, n = 3; 7 d ABS + CS, n = 3 mice). Statistical analysis was not performed because of the small sample size. b, Optical fibre placements for MD–BLA silencing experiments. c, Viral injections used to visualize the MD–BLA projection. The results (d, e) were replicated with seven mice including five mice obtained after whole-cell recording (h). d, Coronal section under excitation with low laser power optimized for visualizing fluorescence in MD area. e, Coronal section under excitation with high laser power optimized for visualizing fluorescence in the BLA complex. CeA, central amygdala. f, Viral injection (top) and whole-cell recording (bottom) for the feedforward inhibition test. g, Sample traces evoked by photostimulation of MD fibres. h, Averaged latencies of EPSCs (B6/J, n = 7; Grik4-cre, n = 8 cells) and IPSCs (B6/J, n = 11; Grik4-cre, n = 6 cells) from the laser onset to 10% rise time. i, j, Light-evoked outward currents recorded at +10 mV were blocked by bicuculline (i) or CNQX and d-AP5 (j), indicating that recorded currents represent feedforward inhibition. k, Fear extinction training for ex vivo recording of MD–BLA synaptic transmission (CS, n = 3; ABS + CS, n = 3 mice). Mixed-design ANOVA: F1,4 = 7.305, P = 0.0539 for group effect. Data shown as mean ± s.e.m. See Supplementary Table 1 for statistical details.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Table

This table contains detailed statistical results.

Video 1: Fear extinction with ABS-paired CS reduces freezing behaviour.

The CS group (conventional extinction group) was presented only with the auditory CS during the whole extinction trials (a,b). The first extinction trial of the ABS-paired group (c) was presented only with the auditory CS. Then, the alternating bilateral sensory stimulation (ABS) was paired with the CS beginning at the second extinction trials (d).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Baek, J., Lee, S., Cho, T. et al. Neural circuits underlying a psychotherapeutic regimen for fear disorders. Nature 566, 339–343 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-0931-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-0931-y

This article is cited by

-

Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing in der Behandlung psychosomatischer Störungsbilder

Die Psychotherapie (2025)

-

„Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing“ (EMDR) in der Schmerztherapie

Der Schmerz (2025)

-

How Fear Memory is Updated: From Reconsolidation to Extinction?

Neuroscience Bulletin (2025)

-

The impact of trauma core dimensions on anxiety and depression: a latent regression model through the Post-Traumatic Symptom Questionnaire (PTSQ)

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Memory Trace for Fear Extinction: Fragile yet Reinforceable

Neuroscience Bulletin (2024)

Jeansok Kim

Anthropomorphizing and Neurobiologizing a Potential Treatment For Fear-related Disorders in Humans. A Commentary on Baek et al (2019) https://doi.org/10.1038/s41...

Jeansok J Kim1 and Joseph E. LeDoux2

1Department of Psychology, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195

2Center for Neural Science, New York University, New York, NY 10003

Animal research on threat processing in the brain can potentially contribute to the development of more effective, and non-invasive, treatments for psychopathologies such as phobias, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and other maladies related to fear. In a recent article “Neural circuits underlying a psychotherapeutic regimen for fear disorders” (21 Feb., p. 339), Hee-Sup Shin and his colleagues [1] reported that alternating bilateral sensory stimulation (ABS) significantly abolished what is often called "fear memory" in mice. The study was premised on Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) psychotherapy, founded by psychologist Francine Shapiro [2]. In 1987, while walking in nature, she inadvertently made a self-discovery that her distressing thoughts dissipated as her eyes shifted back and forth, scanning her surroundings [3]. EMDR has, over the years, risen in popularity as a treatment for a host of fear-related illnesses, but also many other conditions, including schizophrenia, tinnitus, and eating disorders.

Since mice cannot be instructed to move their eyes back and forth while imagining dangerous events, Baek and colleagues devised a clever proxy of the human EMDR procedure. Mice were first trained with a 3 kHz tone and aversive footshock pairings (i.e., so-called Pavlovian fear conditioning). During extinction of the conditioned memory, repeated tone presentations were each accompanied by ABS involving bi-directional flashing lights. The results aligned with the therapeutic expectations of EMDR. Specifically, mice exposed to extinction-ABS pairings exhibited a significant decrease in auditory fear memory that did not return with a passage of time (spontaneous recovery), or with a change in environment (renewal). In contrast, animals that experienced standard extinction or unpaired extinction/ABS showed spontaneous recovery and renewal, effects which also occur after cognitive behavior therapy, which is, in part, based on extinction. Next, Shin and colleagues used state of the art methods (single unit recordings, optogenetics, genetically modified mouse) to demonstrate that a specific increase in tonic (but not bursting) neural activity in a specific circuit involving the superior colliculus-mediodorsal thalamus was both necessary and sufficient to produce lasting effects of ABS on the conditioned responses.

These findings, though impressive, need to be cautiously interpreted in relation to EMDR. For one thing, what is called "fear" in preclinical studies of animals typically conflates the experience of fear, which is a central part of human suffering in fear disorders, with behavioral responses to threats [4,5]. Ignoring such differences perpetuates anthropomorphic presuppositions about animal minds, and trivializes the complexity of human fear, which in no small measure depends on cognitive, social and cultural factors. Another important issue, not unrelated to the first, is that the effectiveness of EMDR relative to other treatments is still the subject of considerable debate [6-9], in part because the underlying mechanisms of psychotherapies in general, and EMDR in particular, has been elusive. The suggestion that a specific mechanism underlying EMDR has been discovered in mice might tip the balance in the debate, but for the wrong reason. While the subcortical circuits implicated in the mouse study are common between rodents and

humans, the experience of fear itself may well involve cortical circuits that

are lacking in mice. One important outcome of the mouse study would be a movement in the EMDR community to attempt to determine the degree to which positive effects of EMDR are due to a direct reduction of the experience of fear, as opposed to changes in behavioral and physiological effects (such as a reduction in pathological avoidance and/or hyperarousal), which might secondarily affect the experience of fear.

References

1. Baek J, Lee S, Cho T, Kim S-W, Kim M, Yoon Y, Kim KK, Byun J, Kim SJ, Jeong J, Shin H-S (2019) Neural circuits underlying a psychotherapeutic regimen for fear disorders. Nature 566:339-343.

2. Shapiro F (2018) Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) Therapy (third edition). The Guilford Press: New York.

3. Lilienfeld SO, Arkowitz H (2007) Can moving your eyes back and forth help to ease anxiety? Scientific American 17:10-11.

4. LeDoux JE (2014) Coming to terms with fear. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 111:2871-2878.

5. LeDoux JE, Pine DS (2016) Using neuroscience to help understand fear and anxiety: a two-system framework. American Journal of Psychiatry 173:1083-1093.

6. Herbert JD, Lilienfeld SO, Lohr JM, Montgomery RW, O’Donohue WT, Rosen GM, Tolin DF (2000) Science and pseudoscience in the development of eye movement desensitization of eye movement desensitization and

reprocessing: implications for clinical psychology. Clinical Psychology Review 20:945-971.

7. Davidson PR, Parker KC (2002) Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR): a meta-analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 69:305-316.

8. Chen L, Zhang G, Hu M, Liang X (2015) Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing versus cognitive-behavioral therapy for adult posttraumatic stress disorder: systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 203:443-451.

9. van den Berg DPG, de Bont PAJM, van der Vleugel BM, de Roos C, de Jongh A, Van Minnen A, van der Gaag M (2015) Prolonged exposure vs eye movement desensitization and reprocessing vs waiting list for posttraumatic stress disorder in patients with a psychotic disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 72:259-267.

J.J.K. and J.E.L. discussed the content and wrote the comments.

Lori Zoellner

Lost in Translation—Rodents Watching Flashing LED Chips to Treat Their PTSD: A Clinical Comment on Baek et al. (2019)

Lori A. Zoellner1, David F. Tolin2, Jonathan S. Abramowitz3, & Norah C. Feeny4

1Department of Psychology, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195

2Anxiety Disorders Center, The Institute of Living/Hartford Hospital, Hartford, CT 06106

3Department of Psychology and Neuroscience, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599

4Department of Psychological Science, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH 44106

As experts in the treatment of fear-based disorders, we excitedly look to our colleagues in behavioral neuroscience to explore unique mechanisms of change, helping isolate neural processes and make our interventions more effective and durable. The recent article by Jinhee Baek and colleagues “Neural Circuits Underlying a Psychotherapeutic Regimen for Fear Disorders” (21 Feb., p. 339), premised on Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) psychotherapy, argues that alternating bilateral sensory stimulation (ABS) abolished "fear memory" in mice [1]. This is a strong claim. Its premises and extrapolation to psychotherapy leave us simply “lost in the translation” between basic science and applied clinical science and make us question the broader relevance of their findings.

Though the Baek et al. study was based on the premise of EMDR as a treatment for PTSD, it is noted that other treatments—specifically, cognitive processing therapy (CPT) and prolonged exposure (PE)—have better empirical support as first line interventions for PTSD [2-4]. The vast majority of those who receive these therapies (91.6%) make reliable improvements in symptoms [5] which are retained for five to ten years after treatment, and only a minority retain their PTSD diagnosis at this long-term follow-up (22.2% of CPT, 17.5% of PE) [6]. Moreover, optimistic estimates of evidence quality for CPT and PE suggest that the efficacy of both substantially and meaningfully outstrip the efficacy of EMDR [7]. Thus, the extant literature does not substantiate the argument that EMDR confers superior or more durable outcomes than other trauma-focused psychotherapies, as implied by Baek et al.

We also note that Baek et al. focus on the role of eye movements in the efficacy of EMDR therapy. EMDR is a multicomponent intervention primarily involving (a) repeatedly focusing on traumatic memories, and (b) visually tracking the therapist's back-and-forth finger movements. Thus, an important scientific question is “What is the active ingredient in EMDR: exposure to the traumatic memory or the lateral eye movements?” Notably, in humans, the evidence suggests that the lateral eye movements do not make a contribution over and above the effects of exposure on key outcomes such as PTSD severity [8,9]. Mechanistically, eye movements likely reflect nothing substantial or simply a distraction-like task [10].

We propose that rather than focusing on second-tier treatments [11] with dubious mechanisms of action, translational science would be best served by focusing on neurobiological mechanisms of well-established PTSD treatments such as CPT and PE and by developing more ecologically valid fear conditioning and extinction paradigms. Helpful research would include studies of optimal ways of engaging frontal and hippocampal regions, which modulate amygdala responses to conditioned stimuli [12]. Principles of inhibitory learning [13,14] suggest potential modifications to exposure therapy that maximize prefrontal cortex (PFC) engagement by developing new, non-threat associations and by enhancing retrieval of these newly-learned associations. In addition, continued research into the processes of memory consolidation/reconsolidation and neuronal plasticity would be helpful. Finally, compounds that promote brain activity implicated in extinction consolidation and recall such as yohimbine, an 2-adrenergic receptor antagonist [15], methylene blue, an autoxidizing agent [16], and d-cycloserine (DCS) a partial NMDA receptor agonist [17], serve as proof of concept that the biological mechanisms of cognitive behavioral therapies can be potentiated [18].

The animal model of PTSD used by Baek et al. may not be appropriate for modeling this complex human disorder. PTSD is characterized by persistent fear that is resistant to extinction, often following an evolutionary-primed conditioning event (e.g., sexual assault) with potent visual, auditory, olfactory, and somatic stimuli. Multiple footshocks in rodents simply do not capture this complexity of “fear memory” in humans. Further, individual differences are seldom modeled in rodent paradigms. The vast majority of individuals after powerful conditioning events do not develop chronic psychopathology; rather, the majority experience natural recovery [19,20]. Indeed, PTSD is often considered a failure of natural extinction [21,22]; yet resistance to initial extinction is simply not modeled. Finally, in humans, the majority of conditioned stimuli (CS) and contexts have some evolutionary-primed, negative valence prior to conditioning (e.g., dark alley behind a bar). “CSs” in humans are not typically arbitrary, neutral stimuli (e.g., auditory tone), rather they are often ambiguous and prone to overgeneralization. A “fear memory” in a rodent as implied by the present study simply does not capture the clinical complexity of fear memories seen in PTSD.

Baek et al. go well beyond their data when they conclude that (a) ABS abolished the “fear memory” in rodents and (b) their study provides a neurobiological basis substantiating durable gains of bilateral eye movements in EMDR. Moreover, EMDR does not have as strong of empirical support as other interventions, and its purported mechanisms are not well supported. Thus, suggesting these results support an “…animal model for psychotherapy…” is akin to rodents talking to a psychotherapist—the translation simply fails.

References

1. Baek J, Lee S, Cho T, Kim S-W, Kim M, Yoon Y, Kim KK, Byun J, Kim SJ, Jeong J, Shin H-S (2019) Neural circuits underlying a psychotherapeutic regimen for fear disorders. Nature 566:339-343.