Abstract

Natural products serve as chemical blueprints for most antibiotics in clinical use. The evolutionary process by which these molecules arise is inherently accompanied by the co-evolution of resistance mechanisms that shorten the clinical lifetime of any given class of antibiotics1. Virginiamycin acetyltransferase (Vat) enzymes are resistance proteins that provide protection against streptogramins2, potent antibiotics against Gram-positive bacteria that inhibit the bacterial ribosome3. Owing to the challenge of selectively modifying the chemically complex, 23-membered macrocyclic scaffold of group A streptogramins, analogues that overcome the resistance conferred by Vat enzymes have not been previously developed2. Here we report the design, synthesis, and antibacterial evaluation of group A streptogramin antibiotics with extensive structural variability. Using cryo-electron microscopy and forcefield-based refinement, we characterize the binding of eight analogues to the bacterial ribosome at high resolution, revealing binding interactions that extend into the peptidyl tRNA-binding site and towards synergistic binders that occupy the nascent peptide exit tunnel. One of these analogues has excellent activity against several streptogramin-resistant strains of Staphylococcus aureus, exhibits decreased rates of acetylation in vitro, and is effective at lowering bacterial load in a mouse model of infection. Our results demonstrate that the combination of rational design and modular chemical synthesis can revitalize classes of antibiotics that are limited by naturally arising resistance mechanisms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Natural product antibiotics often have poor characteristics as therapeutic agents1 and are subject to resistance mechanisms that have arisen through coevolution4. A primary method to improve natural antibiotics for human use is semisynthesis—that is, chemical modification of natural products obtained by biological production. This method has improved the pharmacological properties of many natural product classes but has achieved only limited success in overcoming resistance mechanisms1. Recently, advances in chemistry have enabled access to several antibiotic classes by fully synthetic routes that provide renewed methods to overcome resistance5,6.

Streptogramin antibiotics comprise two structurally distinct groups (A and B)3 (Extended Data Fig. 1a) that act synergistically to achieve bactericidal activity in many organisms7 by inhibiting the bacterial ribosome8. Group A antibiotics bind to the peptidyl transferase centre (PTC) and increase affinity for the group B component in the adjacent nascent peptide exit tunnel9. Resistance to the A component mediates high-level resistance to the combination, whereas resistance to the B component results in intermediate resistance10. Similar to other antibiotics that target the PTC, resistance to group A streptogramins can be mediated by the ATP-binding cassette F (ABC-F) family proteins that dislodge antibiotics11 or by Cfr methylases that methylate A2503 of the 23S rRNA to sterically block binding12. A specific resistance mechanism for group A streptogramins is deactivation by virginiamycin acetyltransferases (Vats)2. These proteins acetylate the C14 alcohol, resulting in steric interference and disruption of a crucial hydrogen bond. The combination of vat(A) and vgb(A) genes (which deactivate the B component) is the most clinically relevant streptogramin-resistance genotype in S. aureus in France, where streptogramins (under the trade name Pyostacine) are used orally for skin and soft tissue infections13,14 as well as bone and joint infections15. Semisynthesis has improved water solubility (for example, Synercid16) and increased potency (for example, NXL-10317), but methods to overcome resistance to the class have yet to be discovered. Fully synthetic routes to group A streptogramins have been previously developed18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28, but these routes have not been applied to the synthesis of new analogues. Here we report optimization of our initially reported route18 and its application to the synthesis of analogues designed to overcome streptogramin resistance.

Structure-guided rational design

We hypothesized that group A streptogramins could be engineered to avoid Vat acetylation while maintaining or improving ribosomal binding (Extended Data Fig. 1). We selected the natural product virginiamycin M2 (VM2) as our parent scaffold owing to its ability to be converted to more active analogues by C16 fluorination (for example, flopristin, 4)17. To guide analogue design (maintaining ribosomal activity while overcoming Vat binding), we obtained a 2.5-Å resolution cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) structure of fully synthetic VM2 bound to the Escherichia coli 50S ribosome. Both the quality of the density, enabled by the advantageous properties of the ribosome as a cryo-EM sample, and the model, enabled by forcefield-guided refinement29,30, facilitated our analogue design. We found that the binding determinants agreed with co-crystallographic data for other related group A streptogramins bound to bacterial9,31,32 and archeal33,34 ribosomes.

In the ribosome, the C3 isopropyl group on VM2 participates in hydrophobic interactions with the face of U2585 but otherwise lacks binding interactions and projects towards the tRNA P-site, which suggests that C3 modifications would be tolerated. Similarly, the C4 methyl group and the C6 proton do not appear to make binding interactions and are angled towards the group B streptogramin-binding site in the exit tunnel. By contrast, mutagenesis and crystallography of the resistance enzyme VatA identified key interactions between these groups (C3 isopropyl, C4 methyl and C6 proton) and binding site residues necessary for acetylation2. Structural modifications of these positions might disrupt VatA binding and overcome Vat resistance, but only one semisynthetic streptogramin with modifications at one of these locations has been reported (hydrogenation of the C5–C6 alkene)2,35. Broader semisynthetic modifications of these positions are restricted by the lack of functional groups for chemoselective activation.

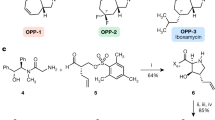

Modular synthesis of structural analogues

To directly test the hypothesis that C3 and C4 structural modifications could overcome Vat-based antibiotic resistance, we first developed a pipeline for the synthesis of group A streptogramins with unprecedented structural diversity. Our route to group A streptogramins (for example, VM2 in Fig. 1a) comprises the convergent assembly of seven simple, individually diversifiable chemical building blocks18. We synthesize two halves of similar complexity, join them by amide bond coupling, and accomplish macrocyclization by means of a Stille cross-coupling reaction. Overall, the route is seven linear steps (eleven total steps) from the starting building blocks, which facilitates rapid generation of analogues. Notably, the syntheses of the halves are highly scalable. By pooling decagram quantities of each, we can rapidly synthesize analogues with modifications on the complimentary half without repeating the entire synthesis. The route depicted in Fig. 1a features technical improvements that increase yield through both the left-half sequence (31% to 40%) and the right-half sequence (18% to 28%) compared to the previous report18.

a, Convergent route to VM2 from seven building blocks. b, Eighteen group A streptogramins accessed by building block variation. The fragments displayed in the dashed boxes represent the structural variability compared to the parent scaffold (VM2). Overall yields for the synthesis of each analogue for the left half sequence (top number) and for the right half sequence (bottom number) are displayed. **Instead of a ketone, madumycin II (34) contains the following substitution at C16: α-H, β-OH. c, Access to 34 analogues (17 in each diastereomeric series) with C3 side-chain variability by means of carbamate formation followed by desilylation. d, Synthesis of tertiary-amine-containing analogues by oxidation and reductive amination. e, C16-fluorinated analogues. DCC, N,N′-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide; DMAP, 4-dimethylaminopyridine; HATU, hexafluorophosphate azabenzotriazole tetramethyl uronium; OTBS, O-(tert-butyldimethylsilyl)hydroxylamine.

We were readily able to prepare 18 streptogramins by building block variation, including the natural products VM2, virginiamycin M1 (VM1), madumycin i (33) and madumycin ii (34) (Fig. 1b). The template synthesis of VM2 was used directly or with trivial modifications (for example, a deprotection step) in most cases to deliver analogues in good yield (10–40% overall). For certain analogues, efficiency was affected by functional group incompatibilities with the chemistry for assembly, and a modified route was required (Supplementary Information).

The incorporation of modified building blocks represents an effective approach to access new analogues, but the diversity of our library is further enhanced by incorporating functional handles for late-stage diversification. We selected C3 for diversification owing to the substantial space for expansion from this position into the tRNA P-site in the ribosome. Replacement of isobutyraldehyde (7) with para-methoxybenzyl-protected (R)- or (S)-3-hydroxy-2-methylpropanal in the left-half sequence enabled access to C3-isopropyl-modified analogues 38 and 39 (>1 g of each prepared) (Fig. 1c). Each of these alcohol-appended streptogramins was allowed to react with 17 commercially available arylisocyanates, resulting in 34 new streptogramin analogues with arylcarbamate side chains at the C3 position (40a-q and 41a-q). The alcohols in 38 and 39 also served as effective precursors for the installation of secondary amines by oxidation or reductive amination (42–44) (Fig. 1d) and for incorporation of fluorine by treatment with diethylaminosulfur trifluoride. In addition, we installed fluorine at C16 by a four-step sequence, providing the clinical candidate flopristin (4) and several fluorinated analogues (Fig. 1e).

In vitro and in vivo efficacy

We evaluated the activity of 62 new group A streptogramin analogues (Extended Data Fig. 2), four natural products, and the first fully synthetic sample of flopristin (4) against a panel of 20 pathogens (Fig. 2a, Extended Data Figs. 3, 4), including three strains with known mechanisms of streptogramin resistance (VatA and Cfr in S. aureus, and ABC-F in Enterococcus faecalis). We also measured in vitro ribosomal translation inhibitory activities for selected analogues (Fig. 2a, blue bars on the right). Installation of a methyl group at C9 (23) or removal of the C12 methyl group (24) resulted in loss of activity. The latter result may provide biological rationale for the four additional biosynthetic steps required for its installation36. Introduction of a primary or tertiary amine (32 or 42, respectively) resulted in complete loss of activity, but notably, 42 inhibited translation in vitro as effectively as VM2. The poor cellular activity probably results from decreased entry or increased efflux, highlighting the challenge of designing antibiotics with both high on-target activity and high cellular accumulation37. Analogues 26, 40q, and 21 displayed equal or improved activity against wild-type and VatA S. aureus compared to VM2, and their C16-fluorinated homologues (45, 46, and 47) exhibited substantially improved activity. Notably, analogues 46 and 47 were 16- to 32-fold more potent against wild-type and VatA S. aureus than flopristin (4). Furthermore, 47 had measurable activity (32 μg ml−1) against ABC-F-expressing E. faecalis11,38 and Gram-negative E. coli (16 μg ml−1), species that are highly resistant to streptogramins. These results support the hypothesis that modifications to C3 and C4 of the group A streptogramin scaffold can overcome resistance caused by Vat proteins while improving antimicrobial activity.

a, MIC values for selected analogues against an expanded panel of pathogens. Each MIC was obtained in technical triplicate. The bars to the right display in vitro translation that occurs in the presence of 10 μM of each analogue (relative to dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO)). b, MIC values against clinical isolates of S. aureus with Vat resistance genes. Ranges of values obtained from technical replicates are displayed; asterisks indicate MIC values that were obtained in technical triplicate and biological triplicate. c, A mouse thigh model of infection with S. aureus CIP 111304 (n = 5 biologically independent animals per group, with the exception of the 2 h infection control where n = 4 per group, examined over one experiment). Each mouse is individually plotted, the centre line is the mean, and the upper and lower whiskers bound the standard deviation from the mean. For detailed statistical analysis, see Extended Data Table 3. CFU, colony-forming units.

Modifications that improve the activity of the group A component may not be compatible with the B component7. For example, C4 extensions into the nascent peptide exit tunnel may clash with the B component. Encouragingly, the combination of C3-modified 46 and even C4-modified 47 with the group B streptogramin virginiamycin S1 (VS1) resulted in improved activity in many strains. In many cases, growth was completely inhibited even at the lowest concentration tested (Fig. 2a). In E. faecalis, substantial improvements in the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) were observed for 46–VS1 (>64, 2 μg ml−1 to 0.5 μg ml−1) and 47–VS1 (32, 2 μg ml−1 to 0.25 μg ml−1). In most strains, 47–VS1 was considerably more potent than the two antibiotics linezolid and daptomycin, which are used to treat multidrug-resistant Gram-positive bacterial infections (Extended Data Fig. 3). These results highlight the use of synergistic combinations of streptogramin and demonstrate that group A streptogramin analogues can facilitate improved activity of the combination.

We tested 47 against an expanded panel of clinical isolates of S. aureus that contain vat genes. Vat genes are often accompanied by vga genes, which encode ABC-class proteins that also confer resistance to group A streptogramins13,14 (Fig. 2b). Notably, strains in this panel also contained resistance genes to several other classes of antibiotics, such as β-lactams, tetracyclines, and aminoglycosides (see the CRBIP catalogue; https://catalogue-crbip.pasteur.fr/recherche_catalogue.xhtml). As expected, VM2 did not effectively inhibit the growth of these streptogramin-resistant strains. Flopristin (4) exhibited good-to-moderate activity (2–16 μg ml−1), and 47 showed excellent-to-moderate activity (0.5–16 μg ml−1). These data demonstrate that the fully synthetic, C4-modified streptogramin 47 is effective at inhibiting the growth of multidrug-resistant clinical isolates with group A streptogramin-resistance genes, often with greater effectiveness than the clinical candidate flopristin (4).

Given the promising in vitro activity of 47 against streptogramin-resistant strains, we next tested its efficacy in a mouse thigh model of infection using S. aureus CIP 111304 (strain 2), a strain that exhibits a high level of group A streptogramin resistance (Fig. 2c). At 10 mg kg−1, compound 47 showed an approximately 10-fold reduction in bacterial load compared to the 24-h infection control (P = 0.001) (Extended Data Table 3), which was similar to high-dose flopristin (4) (200 mg kg−1). At 200 mg kg−1, 47 demonstrated a roughly 100-fold reduction in bacterial load compared to the 24-h infection control (P = 0.001). It is especially notable that compound 47 demonstrates notable potency in this demanding model of infection, even in the absence of a synergistic group B streptogramin partner.

Mechanisms of action and resistance

In agreement with their low MIC values, 4 (half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of 40 ± 10 nM (mean ± s.d.)) and 47 (IC50 of 70 ± 20 nM) inhibited translation more effectively than VM2 (IC50 of 500 ± 200 nM) in vitro (Fig. 3a). The similar IC50 values of 4 and 47 suggest that their MIC differences are due to factors other than improved ribosome inhibition. To quantify deactivation by VatA, we measured rates of C14 acetylation using purified VatA for 4 and 47. The approximately 2.5-fold reduction in catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) does not linearly account for the 8- to 16-fold reduction in MIC values in the plasmid-mediated VatA S. aureus strain (strain 2) (Fig. 2a–c), but it is similar to the reduction in the MIC values of the clinical isolates of S. aureus (strains 13–19). Nonlinear correlation of MIC value to drug deactivation can result from the contribution of other factors such as cellular accumulation, other resistance mechanisms, and efflux39,40. To determine the structural contributions of 47 to a low rate of VatA acetylation, we obtained an X-ray co-crystal structure (Fig. 3b), which reveals displacement of Leu110 by 1.5 Å compared to VM1 in VatA (PDB code 4HUS2) due to steric clash with the C4 extension of 47.

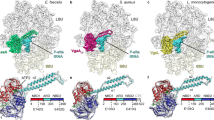

a, Summary of VatA acetylation kinetics and in vitro inhibition of the E. coli ribosome by 4 and 47. Error bars denote s.d. (3 technical replicates). For detailed statistical analysis, see Extended Data Table 3. b, X-ray crystal structures of VM1 bound to VatA (PDB code 4HUS; 2.4 Å) and 47 bound to VatA at 3.2-Å resolution. Distances shown are measured between carbons of the C4 extension of 47 and Leu110 in the VM1-bound VatA structure (in orange dashes, 2.1 Å) and in the 47-bound VatA structure (in marine dashes, 3.6 Å). c, 2.7-Å cryo-EM Coulomb potential density map (contoured in dark blue at 4.0σ and light grey at 1.0σ) for ribosomes bound to 46 and VS1. d, 2.8-Å cryo-EM Coulomb potential density map for ribosomes bound to 47 and VS1. e, Overlay of selected PTC-site antibiotics shows how the side chain of 46 and the extension of 47 occupy areas distinct to previously characterized antibiotics. f, Overlay of P-site tRNA (dark grey, PDB code 1VY4) with the cryo-EM structure of ribosome-bound 46 reveals that the side chain extends into the P-site and mimics the terminal adenosine (A2450) of the tRNA.

To explore the structural basis for antimicrobial activity, we characterized several analogues bound to the E. coli ribosome using cryo-EM (Fig. 3c, d, Extended Data Figs. 5, 6). The PTC is highly conserved across pathogenic species of bacteria, and the E. coli ribosome is an appropriate model for group A streptogramin binding in both Gram-negative and Gram-positive organisms9. The 2.6-Å structure of analogue 47 bound to the ribosome clearly reveals the position of the C4-allyl extension, which projects towards the streptogramin B binding site and makes contacts with A2062, U2585 and U2586 (Extended Data Fig. 5). This extension also adopts a less strained conformation when ribosome-bound than when VatA-bound (calculated −2.3 kcal mol−1) (Extended Data Fig. 7, Extended Data Table 2). This difference, along with protein conformational changes (Fig. 3b), could contribute to the observed differences in acetylation rates between 4 and 47. In the presence of VS1, the C4 extension adopts a strained conformation similar to its conformation in VatA but is probably stabilized by hydrophobic interactions with the B component (Fig. 3d).

Ligand strain may also have a role in the efficacy of 46. Predicted low-energy conformations of 46 position the arylcarbamate extension directly over the macrocycle (Extended Data Fig. 7); however, the structures of 46 bound to the ribosome in the presence or absence of VS1 (Fig. 3b, Extended Data Fig. 5) showed density for the extension in the P-site. The isoquinoline portion of the extension sits between A2602 and C2452, without making specific contacts with either. The proximity of C29 to U2585 may explain the difference in activity between the two diastereomeric series at this position (40a-q and 41a-q) (Fig. 1c). Consistent with this idea, 41q demonstrated poor density for the extension with several conformations. Notably, unlike 47, the modelled position of 46 does not clash with VatA when superposed in the crystal structure (Extended Data Fig. 7). A crystal structure of 46 bound to VatA revealed an extended conformation with poor side-chain density and 10 kcal mol−1 higher calculated internal energies (Extended Data Fig. 7, Extended Data Table 2). Collectively, these results suggest that the ligands adopt distinct, strained conformations when VatA-bound than when ribosome-bound.

The bacterial PTC is a privileged antibiotic-binding site (Fig. 3e). It is notable that the arylcarbamate side chain in 46 and the allyl side chain in 47 do not considerably overlap with other ligands and that they do not preclude binding of VS1. The position of the arylcarbamate side chain in 46 extends into the P-site (Fig. 3f). By overlaying the five-terminal bases of P-site bound tRNA into the structure with 46 and VS1 bound to the catalytic centre (PDB code 1VY441), we discovered that the isoquinoline group in 46 overlaps substantially with the terminal adenosine that is conserved in all tRNAs. Only the non-selective inhibitor blasticidin, which inhibits both eukaryotic and prokaryotic ribosomes, binds this deeply into the P-site by mimicking the cytosines in the CCA tail33. The 23-membered macrocyclic core of the group A streptogramins will probably provide a basis for selectivity for prokaryotic ribosomes that has not been achieved by tRNA mimics such as blasticidin. Further optimization of C3 side chains, guided by cryo-EM characterization, may lead to the design of extremely potent, selective inhibitors of bacterial protein synthesis. This work highlights how cryo-EM is contributing to the determination of structure–activity relationships42,43.

Conclusion

By combining modular chemical synthesis, antibacterial evaluation, in vitro analysis, and high-resolution cryo-electron microscopy, we have developed a pipeline for the synthesis and optimization of group A streptogramin antibiotics. Our approach enabled the preparation of novel analogues by means of building block variation and late-stage diversification, providing valuable structure–activity relationships for the class. Modifications at two previously unexplored positions on the scaffold afforded the first group A streptogramins to overcome resistance caused by Vat enzymes. These C3- and C4-modified analogues can serve as templates for the optimization of both group A streptogramins and other PTC-binding antibiotics, potentially leading to candidates that overcome resistance caused by binding-site modifications such as methylation of A2503 by Cfr methylase. An analogy can be drawn to ketolides such as telithromycin and solithromycin, which possess biaryl side chains that enhance activity against ribosomes modified by erythromycin methyltransferases (Erm resistance)44. Although the emergence of other resistance mechanisms is inevitable, this approach may permit chemical adaptations to extend the clinical longevity of the streptogramin class.

Methods

MIC testing

Compounds were evaluated by Micromyx LLC (Fig. 2a, Extended Data Figs. 3, 4) and at the Collection of Institut Pasteur (Fig. 2b) for MIC activity against a variety of pathogenic bacteria, using the broth microdilution method, as recommended by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Pre-weighed vials of the test agents were stored at −20 °C until testing. On the day of the assay, the compounds were dissolved in 100% DMSO (Sigma 472301, Lot No. SHBH5551V) to a stock concentration of 6,464 μg ml−1. The concentration range tested for each of the compounds was 64–0.06 μg ml−1, and each compound was tested in triplicate. Levofloxacin was used as the quality control agent. For more details on test organisms, medium and methods, see Supplementary Information.

Animal study

The animal study was conducted at the University of North Texas Health Science Center following UNTHSC approved (IACUC) protocol IACUC-2017-049, which has been adapted from comparable literature methods. Test articles were supplied by the Seiple Laboratory in a randomized and blinded fashion. No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample size.

Mice

Female 5–6-week-old CD-1 mice (18–22 g) were used in the studies. The mice were housed in groups of five with free access to food and water during the study. Mice were obtained from Envigo Laboratories. Animals were cared for and housed in accordance with the ‘Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals’ (National Academy Press, Washington DC, 2011). Ambient temperature was kept at 20–26 °C and humidity was kept between 30% and 70%. Mice were kept on a 12 h:12 h cycle and housed according to NIH guidelines.

Pre-treatment

Mice were treated with 150 mg kg−1 and 100 mg kg−1 cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan) by the intraperitoneal route on days −4 and −1.

Infection

Inoculum was prepared in Trypticase Soy Broth (TSB) from an overnight streak plate to approximately 106 CFU ml−1 based on previous experimental growth curve results. Mice were infected by the intramuscular route with 0.1 ml of this adjusted inoculum.

Virulence

Micromyx provided the bacterial strain, S. aureus VatA strain (MMX-10227, CIP 111304), including detailed data on source, purity, in vitro growth characterization, and antibiotic susceptibility. Mice were made neutropenic by cyclophosphamide treatment before infection using standard methods. Bacterial (CFU) burden was evaluated for each group at 2 h after infection and at 24 h after infection using standard methods involving tissue thigh homogenization followed by dilution plating to permit accurate colony counts. Mice were inoculated with 5.75 log10(CFU) of S. aureus MMX-10227 (with the inoculum prepared from fresh plates with 10 μg ml−1 VM1) and thigh samples taken at 2 and 24 h after -infection. Plate counts performed on Mueller-Hinton Agar (MHA) + 10 μg ml−1 virginiamycin, Brain Heart Infusion Agar (BHI) + 0.5% charcoal, and mannitol salts agar were comparable with mean bacterial thigh titres of 6.74–6.78 log10(CFU) at 2 h and 8.20–8.61 log10(CFU) at 24 h.

Tolerance

Test articles and a vehicle dose group were administered subcutaneously in a volume of 0.5 ml. The formulation selected for use was 10% DMSO in 25% hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (hpbCD). Mice were administered a single subcutaneous dose of each test article at 50, 100 and 200 mg kg−1. For each of the dose groups in the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) determination study, three mice were used for each dose level. The use of three mice is sufficient for the determination of the MTD and this group size and proceeding in an ascending stepwise manner will allow for the use of as few animals as possible. Survival and general observations (breathing, mobility, reactions) as to the tolerability of the administered dose immediately following and for a period of time after each dose were recorded. Test articles were well tolerated over the dose range of 50, 100 and 200 mg kg−1 administered subcutaneously. There were no immediate adverse effects observed, and all mice appeared alert and responsive after observations at 0.5, 2, 14 and 24 h after dosing.

Efficacy study

All dosing was subcutaneous starting at 2 h after infection. Test articles were administered as a single dose to mice at 10, 20, 50, 100 and 200 mg kg−1. For each of the dose groups, five mice were used at each dose level. The dosing samples were prepared fresh. Bacterial CFU/thigh at 2 h (control) and 24 h after infection were determined. Mice were euthanized by CO2 inhalation, skin reflected and thighs aseptically removed, placed in 2 ml cold sterile PBS, homogenized using a Polytron tissue homogenizer, serially diluted and plated on Mueller-Hinton Agar + 10 μg ml−1 virginiamycin (MHA+V).

In vitro translation assay 10-μM screen

The ability of group A streptogramin analogues to inhibit the 70S E. coli ribosome was first screened using the PURExpress In Vitro Protein Synthesis Kit (E6800, NEB), murine RNase inhibitor (M0314, NEB), and 6.66 ng μl−1 of template DNA encoding the fluorescent protein mEGFP (gift from the Cate laboratory). The volume of the reaction mixture was scaled down fivefold from the NEB protocol for a final reaction volume of 5 μl. Analogues were screened at a final concentration of 10 μM in 10% DMSO. Translation reactions were carried out in triplicate at 37 °C for 1 h, then transferred to a 0 °C metal block. To assist in the transfer of reactions to 96-well half-area Non-Binding Surface (NBS) microplates (Corning 3993) for final measurements, the reaction volume was increased to 50 μl by adding buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 60 mM NH4Cl, 6 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EDTA). Using a Cytation 5 plate reader (BioTek), translated mEGFP was excited at 485 nm; its emission was recorded at 535 nm. For comparison of analogue activities across multiple initial screens, fluorescence readouts were normalized to the blank. Data were analysed using Microsoft Excel.

In vitro translation assay for IC50 determination

IC50 values of group A streptogramin analogues were determined using the PURExpress ∆ Ribosome Kit (E3313, NEB) for in vitro protein synthesis, 70S E. coli ribosomes (P0763S, NEB), murine RNase inhibitor (M0314, NEB), and 6.66 ng μl−1 of template DNA encoding the fluorescent protein mEGFP (gift from the Cate laboratory). This kit was specifically used to achieve a final ribosome concentration of 24 nM. The volume of the reaction mixture was scaled down fivefold from the NEB protocol for a final reaction volume of 5 μl. Analogues were tested in a range from 0 to 36 μM in 10% DMSO (final concentration). Translation reactions were carried out in triplicate in a 37 °C water bath for 4 h, then transferred to a 0 °C metal block. To assist in the transfer of reactions to 96-well half-area NBS microplates (Corning 3993) for final measurements, the reaction volume was increased to 50 μl by adding buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 60 mM NH4Cl, 6 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EDTA). Using a Cytation 5 plate reader (BioTek), translated mEGFP was excited at 485 nm; its emission was recorded at 535 nm. Raw data were processed and visualized using Python 2.7 and Matplotlib 2.0.2; the script is available on github. The IC50 value was interpreted by fitting the dose response curve to the following equation, where ‘top’ and ‘bottom’ are the values of the plateaus: y = bottom + (top − bottom)/(1 + (x/IC50)).

VatA cloning, expression and purification

This protocol was adapted from that previously described2.The S. aureus VatA sequence from residues 7 to 219 was cloned into the pET28a plasmid with an N-terminal 6xHis-tag followed by a tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease cleavage site. The plasmid was transformed into E. coli BL21 cells for VatA protein expression. Bacterial cultures were grown at 37 °C with shaking to an OD600 of approximately 0.6–0.8, then induced with IPTG at a final concentration of 0.5 mM. After induction, the cultures were grown at 16 °C with shaking and were collected 20–22 h later. Cells were resuspended into 50 ml of 50 mM HEPES pH 7.8, 10 mM imidazole pH 7.8, 300 mM NaCl, and EDTA-free protease inhibitor (11836170001, Roche) and then sonicated using 5 rounds of 30 s pulses with a 60 s wait period. The lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 35,000 rcf for 45 min at 4 °C. Supernatant was passed over a 5 ml Ni-NTA column (HisTrap FF, GE Healthcare), washed with 50 mM HEPES pH 7.8, 20 mM imidazole pH 7.8, 300 mM NaCl, and eluted using a 50–500 mM imidazole pH 7.8 gradient. The protein was dialysed (10,000 MWCO) into 25 mM HEPES pH 7.8, 150 mM NaCl and simultaneously cleaved using 6xHis-tagged TEV protease45 in a 1:10 ratio by weight for 48 h at 4 °C. The sample was passed a second time through a Ni-NTA column (HisTrap FF, GE Healthcare), and VatA was collected in the wash. For enzymology, the sample was passed over a Superdex 200 16/600 sizing column (GE Healthcare) with 25 mM HEPES pH 7.8, 150 mM NaCl and collected in the elution. For both enzymology and crystallography, purified protein was concentrated and stored at −80 °C until further use.

VatA acetylation assay

Acetylation assays were performed in 96-well clear polystyrene flat-bottom NBS plates (Corning 3641) at 100 μl of 50 mM HEPES pH 7.8, 0.5 mM 5,5′-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB or Ellman’s Reagent), 1 mM acetyl-CoA (AcCoA), 29 nM TEV-cleaved enzyme, and 0 to 0.4875 or 0.65 μM streptogramin A analogue2,46. Analogues were diluted from stock solutions prepared at 35 mM compound in 80% ethanol; the final amount of ethanol in the acetylation reaction was 2%. All reactions were carried out in triplicate. Immediately upon adding enzyme, the reaction plate was moved to an Epoch 2 plate reader (BioTek) and its wells read at 415 nm for absorbance of the yellow TNB, a product of the 1:1 reaction of DTNB with the free sulfhydryl of CoA. Plates were read at room temperature for approximately 8 min with 4 s intervals between each reading of the same well. The quantity of CoA produced as a byproduct of acetylation was determined relative to a CoA standard curve, prepared in duplicate, which contained all components of the reaction solution except analogue, enzyme, and AcCoA, which itself was substituted for 0 to 0.375 mM CoA, final concentrations. Linear regions and slopes of the progress curves were determined in Microsoft Excel using the best fit to a linear regression model, optimizing R2. Using the CoA standard curve, these rates were converted to VatA activity in μmol CoA min−1 mg−1 enzyme. Kinetic information was derived by fitting the data to the following Michaelis–Menten model using a script available on github.

VatA crystallization

Purified VatA was concentrated to 60 mg ml−1 in dialysis buffer (25 mM HEPES pH 7.8, 150 mM NaCl), mixed to a final 2:1 molar ratio (protein:compound) with 10 mM streptogramin analogue in 100% DMSO, and crystallized at room temperature using the hanging drop method with a reservoir volume of 96 μl. After mixing, the samples were filtered through a 0.22-μm filter. For the VatA-46 co-crystal structure, 100 nl of mixed sample were combined with 100 nl of 1 M LiCl, 0.1 M BICINE pH 9, and 10% (w/v) PEG 6K from JCSG Core II (Qiagen) using mosquito LCP (SPT Labtech). For the VatA-47 co-crystal structure, 100 nl of mixed sample were combined with 100 nl of 0.2 M (NH4)2SO4, 0.1 M phosphate-citrate pH 4.2, 20% (v/v) PEG 300, and 10% glycerol from JCSG Core II (Qiagen) using mosquito LCP (SPT Labtech). Both crystals were cryoprotected by a brief transfer into a 2 μl mixture of 75% reservoir solution and 25% glycerol.

X-ray diffraction data collection, processing, and model building

For both crystal structures, the diffraction data were collected at the Advanced Light Source (ALS, Berkeley, CA), beamline 8.3.1, at 92 K with a wavelength of 1.11583 Å using a DECTRIS PILATUS3 6M detector. Data were processed using Xia2 (v.0.6.354)47, which used XDS (v20200131)48 for indexing and integration and XSCALE48 for merging. The resolution cut-off was selected automatically, using the default criteria in Xia2. Model construction was carried out using the PHENIX (v.1.17.1) suite and Coot (v.0.8.9.2) as follows. Structures were solved by molecular replacement using the 4HUR2 VatA trimer and phenix.phaser49. Refinement was performed using phenix.refine with manual model building in Coot50. B-factors were refined individually for the VatA–47 structure and as single residue groups for VatA–46. NCS constraints were applied in the refinement of both structures based on density and consisted of three groups: chains A + E, chains B + F, and chains C + D for VatA–46. The NCS constraints for VatA–47 consisted of: chains A + F, chains B + E, and chains C + D. TLS groups were used based on those used previously for refinement of VatA2. Both VatA–46 and VatA–47 were refined with the OPLS3e/VSGB2.1 force field from Schrӧdinger as described below but using phenix.refine to obtain low energy conformations for the ligands. Data collection and refinement statistics are reported in Extended Data Table 4. To obtain low energy conformations of VM1 in VatA and the E. coli ribosome, respectfully from 4HUS2 and 4U259, the models were refined once using phenix.refine and the VM1 ligand refined with the OPLS3e/VSGB2.1 force field. Ligand energies were then evaluated by Prime with OPLS3e/VSGB2.1 (Extended Data Table 4).

Cryo-EM sample preparation

For cryo-EM analysis, purified 50S ribosomes from E. coli strain MRE60051 were prepared in 50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM potassium acetate, 6 mM magnesium acetate, and 7 mM fresh β-mercaptoethanol (BME). Inhibitor was added, mixed gently, and incubated on ice for 1 h. The final concentration of ribosomes was 100 nM; the final concentration of each inhibitor was 60 μM. For samples prepared with two inhibitors, both were added in a 1:1 ratio. For each grid (Quantifoil holey carbon grids, C2-C14nCu30-01 or N1-C14nCu40-01, Quantifoil Micro Tools Gmbh), 3.5 μl of sample was deposited onto a freshly glow-discharged (EMS-100 Glow Discharge System, Electron Microscopy Sciences, 30 s at 15 mA) grid and incubated for 30 s at 25 °C and 100% humidity. Grids were vitrified by plunge-freezing into liquid ethane52 using a FEI Vitrobot Mark IV (ThermoFisher). To achieve optimal ice quality for collection, liquid was blotted from the grid using Whatman #1 filter paper and multiple grids for each sample were frozen with a range of different blotting times. Grids were screened using a FEI Talos Arctica electron microscope (ThermoFisher, operating at 200 kV, located at UCSF) to check ice quality and identify the optimum grids for data collection.

Cryo-EM data collection

All datasets were collected on FEI Titan Krios electron microscopes (ThermoFisher, operating at 300 kV, located at UCSF or NCCAT), with the exception of 40q, which was collected on a FEI Talos Arctica electron microscope (ThermoFisher, operating at 200 kV, located at UCSF). Automated data collection at UCSF was facilitated by SerialEM (v3.6)53; collection at NCCAT was via Leginon (v.3.4)54. The 50S with 47–VS1 bound data et was collected on a K3 (Gatan) Direct Electron Detector (DED) with a Gatan Imaging Filter (Gatan, 20 eV slit) using a nine-shot beam-image shift approach with coma compensation55. The 50S with 47 bound and the 50S with 46–VS1 bound data sets were collected using a four-shot beam-image shift approach with coma compensation on a K2 Summit DED (Gatan). All other datasets were collected on-axis using a K2 Summit DED (Gatan). Pixel sizes, number of images in dose-fractionated micrographs, dose rates, and defocus ranges varied slightly and are reported in Extended Data Table 5. All image stacks were collected in super-resolution mode.

Cryo-EM image and data processing

Super-resolution image stacks were binned by a factor of 2, corrected for beam-induced motion, and dose-weighted using MotionCor2 (v.1.2.1)56. All Coulomb potential density maps were reconstructed in cisTEM (1.0.0-beta)57 using dose-weighted micrographs. Initial CTF parameters were determined using CTFFIND4, included as part of the cisTEM package, with the resolution range between 30 and 4 Å included in the fitting. Bad micrographs (crystalline ice, poor CTF fits) were excluded from processing through visual inspection. Particles were picked in cisTEM by matching to a soft-edged disk template with a maximum particle radius of 110 Å and a characteristic particle radius of 90 Å. The number of particles picked from all micrographs and from good micrographs is found in Extended Data Table 5. CisTEM refinement packages were made using a particle molecular weight of 1,800 kDa. Particles were 2D-classified into 50 classes with a mask radius of 150 Å. Classes containing the 50S ribosome were carried forward into single-class auto refinement with an outer mask radius of 125 Å and a default starting resolution of 20 Å. A filtered volume was used to make a binary mask; the volume eraser tool from UCSF Chimera (v.1.12)58 was used to exclude the mobile L1 stalk from the mask. This mask was used in single-class manual refinement with a final high-resolution limit of either 3.50 or 3.00 Å (see Extended Data Table 5). Unsharpened maps were used in model refinement and for all figures.

Cryo-EM model building and refinement with OPLS3e

We used UCSF Chimera (v.1.12) to rigid body align a high-resolution X-ray structure of the E. coli ribosome (PDB code 4YBB59) into our maps. Principle versions of the PHENIX suite used for cryo-EM model building were 1.14, dev-3406, 1.16, and 1.17. Initially, the ligand restraints files (CIF files) were generated with phenix.eLBOW60 using the analogue’s SMILES string and a ‘final geometry’ reference PDB of the analogue that was derived from the pose of flopristin bound to the E. coli ribosome (PDB code 4U209). These ligands were superimposed into 4YBB based on the binding pose of flopristin in 4U20, and manual edits to the surrounding structure were performed in Coot (v.0.8.9.2).

After constructing these initial models, structures were refined using phenix.real_space_refine with the default protocol, initially with CIF restraints files from phenix.eLBOW. These resulted, however, in non-physical high energy conformations of the ligands (Extended Data Fig. 1, Extended Data Table 1). To improve the models of the ligands, we used a new version of phenix.real_space_refine interfaced with the OPLS3e/VSGB2.1 force field, a high quality force field for ligands61. This approach allows obtaining physics-based energies and gradients for either the whole or part of the structure without resorting to accurate manual CIF restraint generation. Standard PHENIX restraints were used for the macromolecule, while the ligand was governed by the OPLS3e/VSGB2.1 force field. Precisely, the unliganded complex and ligand were individually prepped using phenix.ready_set and prepwizard, respectively, and subsequently recombined. The recombined complex served as input for refinement using the additional Schrӧdinger-dependent options use_schrodinger = True maestro_file = ligand.mae schrodinger.selection = “resname LIG”, in which ‘ligand.mae’ describes the ligand structure in Maestro format and LIG is the residue three-letter code, and otherwise default parameters. For models with two ligands, namely 46–VS1 and 47–VS1, VS1 was prepared in the same way as the ligand described above. All refinement for 46–VS1 and 47–VS1 was carried out using PHENIX-OPLS3e/VSGB2.1. Atomic coordinates for VS1 and the companion ligand were merged into one instance in Maestro and exported to one .mae file. Both ligands were included in the Schrӧdinger selection for OPLS3e refinement.

The PHENIX-OPLS3e/VSGB2.1 interface works as follows: the PHENIX refinement engine spawns an external process serving as an energy server, initialized with the ligand structure present in the provided maestro_file option. When the refinement engine requests energies and gradients, the ligand’s internal coordinates are written to file and read in by the external server. After updating ligand coordinates on the server side, the energy and gradients are calculated and exchanged with the refinement engine. The refinement engine on its side updates the ligand energy and gradients contribution in its energy function using a default weight factor of 10 for the OPLS3e/VSGB2.1 energies. Refinement with the OPLS3e/VSGB2.1 force field reduced the energy for all ligands compared to the conformations refined using CIF based restraints calculated by phenix.eLBOW (Extended Data Table 1).

For all cryo-EM figures, the full, unsharpened density maps and full PDB models were boxed using phenix.map_box with a selection radius of 20 Å around the ligand(s). Boxed map and model were loaded into PyMol (incentive v.2.2.3) with set normalize_ccp4_maps, off. Maps were contoured at 4σ for tight density (dark blue) and 1σ for loose density (light grey), both centred around the ligand with a carve of 1.8.

Quantum mechanical calculations

Calculations were based on the scaffold of flopristin (4) from the crystal structure bound to the ribosome9. Compound 46 was constructed using the LigPrep tool of Maestro (v2019-4, Schrӧdinger Inc.). First, the macrocycle conformation sampling method62 was validated by comparison to the low energy pose as that of the co-crystal structure of flopristin (4). By using the thorough sampling intensity strategy, 1000 conformations of 46 were obtained, and the lowest prime energy pose with the r.m.s.d. <2 Å (scaffold atoms of 4 as reference atoms) was regarded as the preferred conformation. Finally, the C3 side chain of this preferred conformation was further optimized using Jaguar software63 using the B3LYP/6-31G* basis set by imposing the constraints on the scaffold atoms.

Statistical analyses

Statistical evaluation of data was carried out in Microsoft Excel as follows: mouse thigh infection model data (24-h control, 4, 47) were analysed using a one-way ANOVA followed by a post hoc Tukey’s test. MIC data (4, 47) in strain 2 (CIP 111304) were evaluated by a Mann–Whitney U test. Kinetics data (4, 47) were analysed using a two-tailed unpaired t-test and a Cohen’s d. All values are reported in Extended Data Table 3.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this paper.

Data availability

Models and maps generated during this study are available in the EMDB and PDB (accessions are listed in Extended Data Tables 4 and 5). Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Forcefield-based refinement is available in PHENIX (versions 1.15 and later) using beta features available in Schrӧdinger 2019-3. Python code for analysing IVT data and VatA kinetics data are available on github: https://github.com/fraser-lab/streptogramin.

References

Wright, P. M., Seiple, I. B. & Myers, A. G. The evolving role of chemical synthesis in antibacterial drug discovery. Angew. Chem. Int. Edn Engl. 53, 8840–8869 (2014).

Stogios, P. J. et al. Potential for reduction of streptogramin A resistance revealed by structural analysis of acetyltransferase VatA. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58, 7083–7092 (2014).

Vazquez, D. in Mechanism of Action (eds Gottlieb, D. & Shaw, P. D.) 387–403 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 1967).

Waglechner, N. & Wright, G. D. Antibiotic resistance: it’s bad, but why isn’t it worse? BMC Biol. 15, 84 (2017).

Seiple, I. B. et al. A platform for the discovery of new macrolide antibiotics. Nature 533, 338–345 (2016).

Charest, M. G., Lerner, C. D., Brubaker, J. D., Siegel, D. R. & Myers, A. G. A convergent enantioselective route to structurally diverse 6-deoxytetracycline antibiotics. Science 308, 395–398 (2005).

Vidaillac, C., Parra-Ruiz, J., Winterfield, P. & Rybak, M. J. In vitro pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic activity of NXL103 versus clindamycin and linezolid against clinical Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes isolates. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 38, 301–306 (2011).

Wilson, D. N. The A-Z of bacterial translation inhibitors. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 44, 393–433 (2009).

Noeske, J. et al. Synergy of streptogramin antibiotics occurs independently of their effects on translation. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58, 5269–5279 (2014).

Hershberger, E., Donabedian, S., Konstantinou, K. & Zervos, M. J. Quinupristin-dalfopristin resistance in Gram-positive bacteria: mechanism of resistance and epidemiology. Clin. Infect. Dis. 38, 92–98 (2004).

Sharkey, L. K. R. & O’Neill, A. J. Antibiotic resistance ABC-F proteins: bringing target protection into the limelight. ACS Infect. Dis. 4, 239–246 (2018).

Leclercq, R. & Courvalin, P. Bacterial resistance to macrolide, lincosamide, and streptogramin antibiotics by target modification. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 35, 1267–1272 (1991).

Haroche, J. et al. Clonal diversity among streptogramin A-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates collected in French hospitals. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41, 586–591 (2003).

Werner, G., Cuny, C., Schmitz, F. J. & Witte, W. Methicillin-resistant, quinupristin-dalfopristin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus with reduced sensitivity to glycopeptides. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39, 3586–3590 (2001).

Valour, F. et al. Pristinamycin in the treatment of MSSA bone and joint infection. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 71, 1063–1070 (2016).

Delgado, G. Jr, Neuhauser, M. M., Bearden, D. T. & Danziger, L. H. Quinupristin-dalfopristin: an overview. Pharmacotherapy 20, 1469–1485 (2000).

Politano, A. D. & Sawyer, R. G. NXL-103, a combination of flopristin and linopristin, for the potential treatment of bacterial infections including community-acquired pneumonia and MRSA. Curr. Opin. Investig. Drugs 11, 225–236 (2010).

Li, Q. & Seiple, I. B. Modular, scalable synthesis of group A Streptogramin antibiotics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 13304–13307 (2017).

Li, Q. & Seiple, I. B. A concise route to virginiamycin M2. Tetrahedron 75, 3309–3318 (2019).

Schlessinger, R. H. & Li, Y.-J. Total synthesis of (−)-virginiamycin M2 using second-generation vinylogous urethane chemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118, 3301–3302 (1996).

Entwistle, D. A., Jordan, S. I., Montgomery, J. & Pattenden, G. Total synthesis of the virginiamycin antibiotic 14,15-anhydropristinamycin IIB. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. I 1315–1317 (1996).

Tavares, F., Lawson, J. P. & Meyers, A. I. Total synthesis of streptogramin antibiotics. (−)-Madumycin II. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118, 3303–3304 (1996).

Ghosh, A. K. & Liu, W. A convergent, enantioselective total synthesis of streptogramin antibiotic (−)-madumycin II. J. Org. Chem. 62, 7908–7909 (1997).

Breuilles, P. & Uguen, D. Total synthesis of pristinamycin IIB. Tetrahedr. Lett. 39, 3149–3152 (1998).

Entwistle, D. A. Total synthesis of oxazole-based virginiamycin antibiotics: 14,15-anhydropristinamycin IIB. Synthesis 1998, 603–612 (1998).

Dvorak, C. A. et al. The synthesis of streptogramin antibiotics: (−)-griseoviridin and its C-8 epimer. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 39, 1664–1666 (2000).

Wu, J. & Panek, J. S. Total synthesis of (−)-virginiamycin M2. Angew. Chem. Int. Edn Engl. 49, 6165–6168 (2010).

Wu, J. & Panek, J. S. Total synthesis of (−)-virginiamycin M2: application of crotylsilanes accessed by enantioselective Rh(II) or Cu(I) promoted carbenoid Si–H insertion. J. Org. Chem. 76, 9900–9918 (2011).

Afonine, P. V. et al. Real-space refinement in PHENIX for cryo-EM and crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D 74, 531–544 (2018).

Li, J. et al. The VSGB 2.0 model: a next generation energy model for high resolution protein structure modeling. Proteins 79, 2794–2812 (2011).

Harms, J. M., Schlünzen, F., Fucini, P., Bartels, H. & Yonath, A. Alterations at the peptidyl transferase centre of the ribosome induced by the synergistic action of the streptogramins dalfopristin and quinupristin. BMC Biol. 2, 4 (2004).

Osterman, I. A. et al. Madumycin II inhibits peptide bond formation by forcing the peptidyl transferase center into an inactive state. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, 7507–7514 (2017).

Hansen, J. L., Moore, P. B. & Steitz, T. A. Structures of five antibiotics bound at the peptidyl transferase center of the large ribosomal subunit. J. Mol. Biol. 330, 1061–1075 (2003).

Tu, D., Blaha, G., Moore, P. B. & Steitz, T. A. Structures of MLSBK antibiotics bound to mutated large ribosomal subunits provide a structural explanation for resistance. Cell 121, 257–270 (2005).

Hoang, N. H. et al. Regio-selectively reduced streptogramin A analogue, 5,6-dihydrovirginiamycin M1 exhibits improved potency against MRSA. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 57, 393–398 (2013).

Kingston, D. G. I., Kolpak, M. X., LeFevre, J. W. & Borup-Grochtmann, I. Biosynthesis of antibiotics of the virginiamycin family. 3. Biosynthesis of virginiamycin M1. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 105, 5106–5110 (1983).

Richter, M. F. et al. Predictive compound accumulation rules yield a broad-spectrum antibiotic. Nature 545, 299–304 (2017).

Sharkey, L. K. R., Edwards, T. A. & O’Neill, A. J. ABC-F proteins mediate antibiotic resistance through ribosomal protection. MBio 7, e01975 (2016).

Radika, K. & Northrop, D. B. Correlation of antibiotic resistance with Vmax/Km ratio of enzymatic modification of aminoglycosides by kanamycin acetyltransferase. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 25, 479–482 (1984).

Knies, J. L., Cai, F. & Weinreich, D. M. Enzyme efficiency but not thermostability drives cefotaxime resistance evolution in TEM-1 β-lactamase. Mol. Biol. Evol. 34, 1040–1054 (2017).

Polikanov, Y. S., Steitz, T. A. & Innis, C. A. A proton wire to couple aminoacyl-tRNA accommodation and peptide-bond formation on the ribosome. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 21, 787–793 (2014).

Renaud, J.-P. et al. Cryo-EM in drug discovery: achievements, limitations and prospects. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 17, 471–492 (2018).

Wong, W. et al. Mefloquine targets the Plasmodium falciparum 80S ribosome to inhibit protein synthesis. Nat. Microbiol. 2, 17031 (2017).

Llano-Sotelo, B. et al. Binding and action of CEM-101, a new fluoroketolide antibiotic that inhibits protein synthesis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54, 4961–4970 (2010).

Tropea, J. E., Cherry, S. & Waugh, D. S. Expression and purification of soluble His6-tagged TEV protease. Methods Mol. Biol. 498, 297–307 (2009).

Kuhn, M. L., Majorek, K. A., Minor, W. & Anderson, W. F. Broad-substrate screen as a tool to identify substrates for bacterial Gcn5-related N-acetyltransferases with unknown substrate specificity. Protein Sci. 22, 222–230 (2013).

Winter, G. xia2: an expert system for macromolecular crystallography data reduction. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 43, 186–190 (2010).

Kabsch, W. XDS. Acta Crystallogr. D 66, 125–132 (2010).

Liebschner, D. et al. Macromolecular structure determination using X-rays, neutrons and electrons: recent developments in Phenix. Acta Crystallogr. D 75, 861–877 (2019).

Emsley, P., Lohkamp, B., Scott, W. G. & Cowtan, K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D 66, 486–501 (2010).

Schuwirth, B. S. et al. Structures of the bacterial ribosome at 3.5 A resolution. Science 310, 827–834 (2005).

Passmore, L. A. & Russo, C. J. Specimen preparation for high-resolution cryo-EM. Methods Enzymol. 579, 51–86 (2016).

Mastronarde, D. N. Automated electron microscope tomography using robust prediction of specimen movements. J. Struct. Biol. 152, 36–51 (2005).

Suloway, C. et al. Automated molecular microscopy: the new Leginon system. J. Struct. Biol. 151, 41–60 (2005).

Cheng, A. et al. High resolution single particle cryo-electron microscopy using beam-image shift. J. Struct. Biol. 204, 270–275 (2018).

Zheng, S. Q. et al. MotionCor2: anisotropic correction of beam-induced motion for improved cryo-electron microscopy. Nat. Methods 14, 331–332 (2017).

Grant, T., Rohou, A. & Grigorieff, N. cisTEM, user-friendly software for single-particle image processing. eLife 7, e35383 (2018).

Pettersen, E. F. et al. UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1605–1612 (2004).

Noeske, J. et al. High-resolution structure of the Escherichia coli ribosome. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 22, 336–341 (2015).

Moriarty, N. W., Grosse-Kunstleve, R. W. & Adams, P. D. electronic Ligand Builder and Optimization Workbench (eLBOW): a tool for ligand coordinate and restraint generation. Acta Crystallogr. D 65, 1074–1080 (2009).

Roos, K. et al. OPLS3e: extending force field coverage for drug-like small molecules. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 15, 1863–1874 (2019).

Sindhikara, D. et al. Improving accuracy, diversity, and speed with prime macrocycle conformational sampling. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 57, 1881–1894 (2017).

Bochevarov, A. D. et al. Jaguar: A high-performance quantum chemistry software program with strengths in life and materials sciences. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 113, 2110–2142 (2013).

Acknowledgements

We thank F. Ward and J. Cate for initial advice on ribosome purifications and translation assays, E.Nogales and a UCSF-UCB Sackler Sabbatical Exchange Fellowship (J.S.F.) for initial cryo-EM access and training. A.A.T. and J.P. were supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program under Grant No. 1650113. D.J.L. was supported by a Postdoctoral Individual National Research Award NIH AI148120. H.A.C. was supported by a National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) research diversity supplement under NIH GM123159. This project was funded by the UCSF Program for Breakthrough Biomedical Research, funded in part by the Sandler Foundation (J.S.F. and I.B.S.), a Sangvhi-Agarwal Innovation Award (J.S.F.), Packard Fellowships from the David and Lucile Packard Foundation (J.S.F. and I.B.S.), NIH GM123159 (J.S.F.), and NIH GM128656 (I.B.S.). We thank G. Meigs and J. Holton at Beamline 8.3.1 at the Advanced Light Source, which is operated by the University of California Office of the President, Multicampus Research Programs and Initiatives grant MR-15-328599, the National Institutes of Health (R01 GM124149 and P30 GM124169), Plexxikon Inc., and the Integrated Diffraction Analysis Technologies program of the US Department of Energy Office of Biological and Environmental Research. The Advanced Light Source (Berkeley, CA) is a national user facility operated by Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory on behalf of the US Department of Energy under contract number DE-AC02-05CH11231, Office of Basic Energy Sciences. We thank M. Thompson for comments on the crystallography methods. We thank A. Myasnikov and D. Bulkley for technical support at the UCSF Center for Advanced CryoEM, which is supported by NIH grants S10OD020054 and S10OD021741 and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI). We thank E. Eng and E. Kopylov for technical support at the National Center for CryoEM Access and Training (NCCAT) and the Simons Electron Microscopy Center located at the New York Structural Biology Center, which is supported by the NIH Common Fund Transformative High Resolution Cryo-Electron Microscopy program (U24 GM129539) and by grants from the Simons Foundation (SF349247) and NY State. We thank W. Weiss at the University of North Texas Health Science Center for conducting the animal study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.L. and I.B.S. determined analogues for synthesis and designed the synthetic routes; Q.L. executed and optimized the syntheses of analogues, with assistance from A.A.T. (analogues 29–32), R.W. (analogue 21), K.J. (analogues 27 and 28), and D.C. (analogue 26); J.P. and D.J.L. prepared samples and collected cryo-EM data; J.P. and A.F.B. calculated cryo-EM reconstructions; J.P. and J.E.P. performed the VatA acetylation assay; J.P. performed the in vitro translation experiments; G.v.Z. and K.B. developed new tools for cryo-EM model refinement; J.P., K.B. and J.T.B. performed cryo-EM model refinements; G.v.Z., J.P., H.A.C., N.Z. and M.P.J. determined relative energies of macrocycle confirmations; H.A.C. collected X-ray crystallographic data and performed X-ray model refinements; D.S., C.W., B.M., E.M, and O.C. designed and executed the MIC assays; Q.L., J.P., I.B.S. and J.S.F. wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

K.B. and G.v.Z. are employees of Schrodinger Inc. D.S., C.W. and B.M. are employees of Micromyx.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature thanks Martin Burke, Gerard Wright and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Fig. 1 Natural and semisynthetic streptogramins and their molecular mechanisms of action and resistance.

a, Selected natural and semisynthetic streptogramin analogues. Modifications installed by semisynthesis are highlighted in blue. b, 2.5-Å cryo-EM structure of VM2 bound to the 50S subunit of the E. coli ribosome. Coulomb potential density is contoured in dark blue at 4.0σ and light grey at 1.0σ. Atom colouring of VM2 mirrors the building blocks used in its synthesis (see Fig. 2). c, Binding interactions between VM2 and residues in the ribosomal binding site. d, X-ray crystal structure VM1 bound to the resistance protein VatA (PDB ID: 4HUS). e, Binding interactions between VM1 and VatA, highlighting the extensive hydrophobic interactions at C3–C6. Acetylation occurs at the C14 alcohol. f, g, Conformational energy of VM2 showing contributions on a per atom basis when refined with standard CIF-based restraints generated by ‘phenix.eLBOW’ (f) and when refined with OPLS3e/VSGB2.1 force field (g). Colour indicates low strain (green, −14 kcal mol−1) up to high strain (red, 10 kcal mol−1), with total conformational energy of 39.5 kcal mol−1 (f) and −88.3 (g). Hydrogens were added and optimized with fixed heavy atoms for the CIF-based refined conformation using ‘prepwizard’; the PHENIX-OPLS3e/VSGB2.1 refined conformation was taken as is. Energies were calculated using Prime and per atom contribution visualized using Maestro’s prime energy visualization.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Inhibitory activity against Gram-positive organisms.

MIC values for selected analogues against an expanded panel of Gram-positive pathogens.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Inhibitory activity against Gram-negative organisms.

MIC values for selected analogues against an expanded panel of Gram-negative pathogens.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Cryo-EM density for all compounds bound to the E. coli ribosome.

a, 2.6-Å cryo-EM structure of VM2 bound to the 50S subunit of the E. coli ribosome. Coulomb potential density is contoured in dark blue at 4.0σ and light grey at 1.0σ for the entire figure. b, 2.8-Å cryo-EM structure of 21 bound to the 50S subunit of the E. coli ribosome. c, 2.8-Å cryo-EM structure of 40e bound to the 50S subunit of the E. coli ribosome. d, 2.5-Å cryo-EM structure of 40o bound to the 50S subunit of the E. coli ribosome. e, 2.8-Å cryo-EM structure of 40q bound to the 50S subunit of the E. coli ribosome. f, 2.6-Å cryo-EM structure of 41q bound to the 50S subunit of the E. coli ribosome. g, 2.5-Å cryo-EM structure of 46 bound to the 50S subunit of the E. coli ribosome. h, 2.5-Å cryo-EM structure of 47 bound to the 50S subunit of the E. coli ribosome. i, 2.7-Å cryo-EM structure of 46/VS1 bound to the 50S subunit of the E. coli ribosome. j, 2.8-Å cryo-EM structure of 47/VS1 bound to the 50S subunit of the E. coli ribosome.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Gold standard and map to model Fourier shell correlation plots.

a–j, The particle Fourier shell correlation (FSC) curves for reconstructions obtained by cisTEM using a molecular mass of 1.8 MDa are shown in blue with unmasked map–model FSC curves obtained from ‘phenix.mtriage’ shown in orange. Dashed lines indicate FSC of 0.143 for estimating gold standard resolution and FSC of 0.5 for estimating map–model resolution.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Conformations of 46 and 47 in the ribosome and in VatA.

a, The conformation of 46 minimized by quantum mechanical methods in low dielectric, shows how the isoquinoline side chain packs over the macrocycle. b, By contrast, the ribosome-bound conformations of 46 determined by cryo-EM show that the side chain extends away from the macrocycle due to interactions formed in the binding site. c, Model of 47 in the conformation bound to the ribosome modelled into the active site of VatA (shown in surface). d, Model of 46 in the conformation bound to the ribosome modelled into the active site of VatA. e, Low energy model of 46 modelled into the active site of VatA. f, Overlay of VatA-bound (marine), ribosome-bound (violet), and ribosome with VS1-bound (light pink) conformations of 47. g, X-ray crystal structures of VM1 bound to VatA (PDB code 4HUS; 2.4 Å) and 46 bound to VatA at 2.8-Å resolution.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Procedures for MIC determination and chemical synthesis.

Supplementary Data

Excel file containing MIC data featured in the manuscript and extended data.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Q., Pellegrino, J., Lee, D.J. et al. Synthetic group A streptogramin antibiotics that overcome Vat resistance. Nature 586, 145–150 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2761-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2761-3

This article is cited by

-

Co-cultivation of Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bacillus subtilis mediates the gut-muscle axis affecting pork quality and flavor

Journal of Animal Science and Biotechnology (2025)

-

A large-scale curated and filterable dataset for cryo-EM foundation model pre-training

Scientific Data (2025)

-

Cationic antimicrobial peptide CC34 potential anticancer and apoptotic induction on cancer cells

Amino Acids (2025)

-

Computer-aided drug design to generate a unique antibiotic family

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Structural basis of Cfr-mediated antimicrobial resistance and mechanisms to evade it

Nature Chemical Biology (2024)