Abstract

The dearth of new medicines effective against antibiotic-resistant bacteria presents a growing global public health concern1. For more than five decades, the search for new antibiotics has relied heavily on the chemical modification of natural products (semisynthesis), a method ill-equipped to combat rapidly evolving resistance threats. Semisynthetic modifications are typically of limited scope within polyfunctional antibiotics, usually increase molecular weight, and seldom permit modifications of the underlying scaffold. When properly designed, fully synthetic routes can easily address these shortcomings2. Here we report the structure-guided design and component-based synthesis of a rigid oxepanoproline scaffold which, when linked to the aminooctose residue of clindamycin, produces an antibiotic of exceptional potency and spectrum of activity, which we name iboxamycin. Iboxamycin is effective against ESKAPE pathogens including strains expressing Erm and Cfr ribosomal RNA methyltransferase enzymes, products of genes that confer resistance to all clinically relevant antibiotics targeting the large ribosomal subunit, namely macrolides, lincosamides, phenicols, oxazolidinones, pleuromutilins and streptogramins. X-ray crystallographic studies of iboxamycin in complex with the native bacterial ribosome, as well as with the Erm-methylated ribosome, uncover the structural basis for this enhanced activity, including a displacement of the \({\text{m}}_{2}^{6}\text{A}2058\) nucleotide upon antibiotic binding. Iboxamycin is orally bioavailable, safe and effective in treating both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacterial infections in mice, attesting to the capacity for chemical synthesis to provide new antibiotics in an era of increasing resistance.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Coordinates and structure factors are deposited in the RCSB Protein Data Bank with accession codes 7RQ8 for the T. thermophilus 70S ribosome in complex with IBX, mRNA, deacylated A-site tRNAPhe, aminoacylated P-site fMet-NH-tRNAiMet, and deacylated E-site tRNAPhe; and 7RQ9 for the \({\text{m}}_{2}^{6}\text{A}2058\) T. thermophilus 70S ribosome in complex with IBX, mRNA, deacylated A-site tRNAPhe, aminoacylated P-site fMet-NH-tRNAiMet. Single-crystal X-ray crystallographic data for compound 6 are deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre under deposition number 2072277. All previously published structures that were used in this work for model building and structural comparisons were retrieved from the RCSB Protein Data Bank under accession codes 6XHW51, 4V7V30 and 1YJN48. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2019 (Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, 2019); www.cdc.gov/DrugResistance/Biggest-Threats html.

Wright, P. M., Seiple, I. B. & Myers, A. G. The evolving role of chemical synthesis in antibacterial drug discovery. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 8840–8869 (2014).

Scientific Roadmap for Antibiotic Discovery (Pew Charitable Trusts, 2016); http://www.pewtrusts.org/antibiotic-discovery.

Charest, M. G., Lerner, C. D., Brubaker, J. D., Siegel, D. R. & Myers, A. G. A convergent enantioselective route to structurally diverse 6-deoxytetracycline antibiotics. Science 308, 395–398 (2005).

Seiple, I. B. et al. A platform for the discovery of new macrolide antibiotics. Nature 533, 338–345 (2016).

Myers, A. & Clark, R. B. Discovery of macrolide antibiotics effective against multi-drug resistant Gram-negative pathogens. Acc. Chem. Res. 54, 1635–1645 (2021).

Li, Q. et al. Synthetic group A streptogramin antibiotics that overcome Vat resistance. Nature 586, 145–150 (2020).

Smith, P. A. et al. Optimized arylomycins are a new class of Gram-negative antibiotics. Nature 651, 189–194 (2018).

Wilson, D. N. Ribosome-targeting antibiotics and mechanisms of bacterial resistance. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 12, 35–48 (2014).

Lin, J., Zhou, D., Steitz, T. A., Polikanov, Y. S. & Gagnon, M. G. Ribosome-targeting antibiotics: modes of action, mechanisms of resistance, and implications for drug design. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 87, 451–478 (2018).

Mason, D. J., Dietz, A. & De Boer, C. Lincomycin, a new antibiotic. I. Discovery and biological properties. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 554–559 (1962).

Birkenmeyer, R. D. & Kagan, F. Lincomycin. XI. Synthesis and structure of clindamycin. A potent antibacterial agent. J. Med. Chem. 13, 616–619 (1970).

Phillips, I. Past and current use of clindamycin and lincomycin. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 7 (Suppl. A), 11–18, (1981).

Birkenmeyer, R. D., Kroll, S. J., Lewis, C., Stern, K. F. & Zurenko, G. E. Synthesis and antimicrobial activity of clindamycin analogs: pirlimycin, a potent antibacterial agent. J. Med. Chem. 27, 216–223 (1984).

O’Dowd, H., Erwin, A. L. & Lewis, J. G. in Natural Products in Medicinal Chemistry (ed. Hanessian, S.) (Wiley-VCH, 2014).

Hirai, Y. et al. Characterization of compound A, a novel lincosamide derivative active against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Antibiot. 74, 124–132 (2021).

Leclercq, R. & Courvalin, P. Bacterial resistance to macrolide, lincosamide, and streptogramin antibiotics by target modification. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 35, 1267–1272 (1991).

Lai, C. J. & Weisblum, B. Altered methylation of ribosomal RNA in an erythromycin-resistant strain of Staphylococcus aureus. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 68, 856–860 (1971).

Griffith, L. J., Ostrander, W. E., Mullins, C. G. & Beswick, D. E. Drug antagonism between lincomycin and erythromycin. Science 147, 746–747 (1965).

Toh, S. M. et al. Acquisition of a natural resistance gene renders a clinical strain of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus resistant to the synthetic antibiotic linezolid. Mol. Microbiol. 64, 1506–1514 (2007).

Long, K. S., Poehlsgaard, J., Kehrenberg, C., Schwarz, S. & Vester, B. The Cfr rRNA methyltransferase confers resistance to phenicols, lincosamides, oxazolidinones, pleuromutilins, and streptogramin A antibiotics. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50, 2500–2505 (2006).

Giessing, A. M. et al. Identification of 8-methyladenosine as the modification catalyzed by the radical SAM methyltransferase Cfr that confers antibiotic resistance in bacteria. RNA 15, 327–336 (2009).

Smith, L. K. & Mankin, A. S. Transcriptional and translational control of the mlr operon, which confers resistance to seven classes of protein synthesis inhibitors. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52, 1703–1712 (2008).

Crowe-McAuliffe, C. et al. Structural basis of ABCF-mediated resistance to pleuromutilin, lincosamide, and streptogramin A antibiotics in Gram-positive pathogens. Nat. Comm. 12 3577 (2021).

Murina, V., Kasari, M., Hauryliuk, V. & Atkinson, G. C. Antibiotic resistance ABCF proteins reset the peptidyl transferase centre of the ribosome to counter translational arrest. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, 3753–3763 (2018).

Mitcheltree, M. J., Stevenson, J. W., Pisipati, A. & Myers, A. G. A practical, component-based synthetic route to methylthiolincosamine permitting facile northern-half diversification of lincosamide antibiotics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 6829–6835 (2021).

Mitcheltree, M. J. A Platform for the Discovery of New Lincosamide Antibiotics. PhD Dissertation, Harvard University (2018).

Silvestre, K. J. Design, Synthesis, and Study of Lincosamide Antibiotics Containing a Bicyclic Amino Acid Moiety. PhD Dissertation, Harvard University (2019).

Moga, I. Novel Lincosamide Antibiotics Containing an Azepane Amino Acid Moiety. PhD Dissertation, Harvard University (2019).

Dunkle, J. A., Xiong, L., Mankin, A. S. & Cate, J. H. Structures of the Escherichia coli ribosome with antibiotics bound near the peptidyl transferase center explain spectra of drug action. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 17152–17157 (2010).

Seiple, I. B., Mercer, J. A., Sussman, R. J., Zhang, Z. & Myers, A. G. Stereocontrolled synthesis of syn-β-hydroxy-α-amino acids by direct aldolization of pseudoephenamine glycinamide. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 4642–4647 (2014).

Kingsbury, J. S., Harrity, J. P. A., Bonitatebus, P. J., Jr & Hoveyda, A. H. A recyclable ru-based metathesis catalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121, 791–799 (1999).

Magerlein, B. J. & Kagan, F. Lincomycin. 8. 4′-alkyl-1′-demethyl-4′-depropylclindamycins, potent antibacterial and antimalarial agents. J. Med. Chem. 12, 780–784 (1969).

Morandi, B. Wickens, Z. K. & Grubbs, R. H. Regioselective Wacker oxidation of internal alkenes: rapid access to functionalized ketones facilitated by cross-metathesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 9751–9754 (2013).

Scheiper, B., Bonnekessel, M., Krause, H. & Fürstner, A. Selective iron-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions of Grignard reagents with enol triflates, acid chlorides, and dichloroarenes. J. Org. Chem. 69, 3943–3949 (2004).

Mason, J. D., Terwilliger, D. T., Pote, A. R. & Myers, A. G. Practical gram-scale synthesis of iboxamycin, a potent antibiotic candidate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 11019–11025 (2021).

Zhao, C. et al. Investigation of antibiotic resistance, serotype distribution, and genetic characteristics of 164 invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae from north China between April 2016 and October 2017. Infect. Drug Resist. 13, 2117–2128 (2020).

Weiner-Lastinger, L. M. et al. Antimicrobial-resistant pathogens associated with adult healthcare-associated infections: Summary of data reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network, 2015–2017. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 41, 1–18 (2020).

Singh, K. V., Weinstock, G. M., Murray, B. E. An Enterococcus faecalis ABC homologue (Lsa) is required for the resistance of this species to clindamycin and quinupristin–dalfopristin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46, 1845–1850 (2002).

Rice, L. B. Challenges in identifying new antimicrobial agents effective for treating infections with Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Clin. Infect. Dis. 43, S100–S105 (2006).

O’Shea, R. & Moser, H. E. Physicochemical properties of antibacterial compounds: implications for drug discovery. J. Med. Chem. 51, 2871–2878 (2008).

Richter, M. F. et al. Predictive compound accumulation rules yield a broad-spectrum antibiotic. Nature 545, 299–304 (2017).

Orelle, C. et al. Tools for characterizing bacterial protein synthesis inhibitors. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57, 5994–6004 (2013).

Vester, B. & Douthwaite, S. Macrolide resistance conferred by base substitutions in 23s rRNA. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45, 1–12 (2001).

Böttger, E. C., Springer, B., Prammananan, T., Kidan, Y. & Sander, P. Structural basis for selectivity and toxicity of ribosomal antibiotics. EMBO Rep. 2, 318–323 (2001).

Silver, L. L. Multi-targeting by monotherapeutic antibacterials. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 6, 41–55 (2007).

Orelle, C. et al. Identifying the targets of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase inhibitors by primer extension inhibition. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, e144 (2013).

Tu, D., Blaha, G., Moore, P. B. & Steitz, T. A. Structures of MLSBK antibiotics bound to mutated large ribosomal subunits provide a structural explanation for resistance. Cell 121, 257–270 (2005).

Polikanov, Y. S., Steitz, T. A. & Innis, C. A. A proton wire to couple aminoacyl-tRNA accommodation and peptide-bond formation on the ribosome. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 21, 787–793 (2014).

Polikanov, Y. S., Melnikov, S. V., Soll, D. & Steitz, T. A. Structural insights into the role of rRNA modifications in protein synthesis and ribosome assembly. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 22, 342–344 (2015).

Svetlov, M. S. et al. Structure of Erm-modified 70S ribosome reveals the mechanism of macrolide resistance. Nat. Chem. Biol. (2021).

Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria That Grow Aerobically, Approved Standard 11th edn (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 2018).

Methods for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing of Anaerobic Bacteria; Approved Standard 8th edn (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 2012).

Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing 27th edn (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 2017).

Odenholt-Tornqvist, I., Löwdin, E., Cars, O. Pharmacodynamic effects of subinhibitory concentrations of β-lactam antibiotics in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 35, 1834–1839 (1991).

Niles, A. L. et al. A homogeneous assay to measure live and dead cells in the same sample by detecting different protease markers. Anal. Biochem. 366, 197–206 (2007).

Marroquin, L. D., Hynes, J., Dykens, J. A., Jamieson, J. D. & Will, Y. Circumventing the Crabtree effect: replacing media glucose with galactose increases susceptibility of HepG2 cells to mitochondrial toxicants. Toxicol. Sci. 97, 539–547 (2007).

Orelle, C. et al. Identifying the targets of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase inhibitors by primer extension inhibition. Nucleic Acids Res. 41 e144 (2013).

Kabsch, W. XDS. Acta Crystallogr. D 66, 125–132 (2010).

McCoy, A. J. et al. Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 40, 658–674 (2007).

Liebschner, D. et al. Macromolecular structure determination using X-rays, neutrons and electrons: recent developments in Phenix. Acta Crystallogr. D 75, 861–877 (2019).

Emsley, P., Lohkamp, B., Scott, W. G. & Cowtan, K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D 66 486–501 (2010).

Schuttelkopf, A. W. & van Aalten, D. M. F. PRODRG: a tool for high-throughput crystallography of protein-ligand complexes. Acta Crystallogr. D 60, 1355–1363 (2004).

The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System v.2.0 (Schrödinger, 2017).

Acknowledgements

We thank C.-W. Chen for help with initial X-ray diffraction data collection; M. Svetlov for providing Erm-methylated ribosomes used in our structural studies; D. R. Andes, M. S. Gilmore, F. H. Lebreton, T. J. Dougherty, D. P. Nicolau, P. Courvalin, C. Grillot-Courvalin, H. E. Moser, S. Chiang, B. Wohl, C. Keith, S. Lahiri, R. Duggal and K. M. Otte for their invaluable input in the course of our research; the staff at NE-CAT beamlines 24ID-C and 24ID-E for their help with data collection, especially M. Capel, F. Murphy, I. Kourinov, A. Lynch, S. Banerjee, D. Neau, J. Schuermann, N. Sukumar, J. Withrow, K. Perry and C. Salbego; S.-L. Zheng for X-ray crystallographic data collection and structure determination of compounds 6 and OPP-3; D. L. Shinabarger and C. Pillar of Micromyx, L.L.C., W. J. Weiss of the UNT Health Science Center and M. D. Cameron of TSRI Florida for in vitro profiling of compounds. Ligand Pharmaceuticals kindly provided the Captisol used in our mouse experiments. M.J.M. was supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship under grant no. DGE1144152. K.J.Y.W. was supported by a National Science Scholarship (PhD) by the Agency for Science, Technology and Research, Singapore. G.T. received postdoctoral support from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (TE1311-1-1). This work is based upon research conducted at the Northeastern Collaborative Access Team (NE-CAT) beamlines, which are funded by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences from the National Institutes of Health (P30-GM124165). The Eiger 16M detector on 24ID-E beamline is funded by a NIH-ORIP HEI grant (S10-OD021527 to NE-CAT). This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. Extraordinary facility operations were supported in part by the DOE Office of Science through the National Virtual Biotechnology Laboratory, a consortium of DOE national laboratories focused on the response to COVID-19, with funding provided by the Coronavirus CARES Act. This work was supported by Illinois State startup funds to Y.S.P. and National Institutes of Health R21-AI137584 (to A.S.M. and Y.S.P.), R01-GM132302 (to Y.S.P.), and R35GM127134 (to A.S.M.). A.G.M. gratefully acknowledges support from the LEO Foundation (grant LF18006) and the Blavatnik Biomedical Accelerator at Harvard University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.J.M. identified the oxepanoprolinamide scaffold and the synthetic routes used to prepare analogues OPP-1, OPP-2, OPP-4 and OPP-5. A.P. designed and performed MIC, TK, PAE, PA-SME and mouse infection experiments. E.A.S. and Y.S.P. designed and performed X-ray crystallography experiments. K.J.S. identified 7′-alkyl oxepanoprolinamides and the synthetic route used to prepare analogues OPP-6, epi-OPP-3 and IBX (OPP-3) from ketone 10. D.K. and A.S.M. selected and sequenced IBX-resistant SQ110DTC clones and conducted ribosome toeprinting analysis. M.J.M., K.J.S., J.D.M., D.W.T., G.T., A.R.P. and K.J.Y.W. synthesized and characterized oxepanoprolinamide analogues. A.P. and R.P.L. performed mammalian cell experiments. A.P. and K.C. designed and performed the pharmacokinetic experiments. A.G.M., A.S.M. and Y.S.P. supervised the experiments. All authors interpreted the results. M.J.M, A.G.M, A.S.M, and Y.S.P. wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

A.G.M., M.J.M., K.J.S., J.D.M. and G.T are inventors in a provisional patent application submitted by the President and Fellows of Harvard College covering antibiotics of the type described in this work. A.G.M., M.J.M. and K.J.S. have filed an international patent application WO/2019/032936 ‘Lincosamide Antibiotics and Uses Thereof’. A.G.M. and M.J.M. have filed an international patent application WO/2019/032956 ‘Lincosamide Antibiotics and Uses Thereof’.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature thanks Daniel Wilson, William Wuest and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

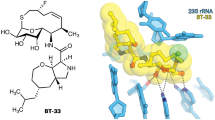

Extended Data Fig. 1 Structure-based design of 7′-substituted oxepanoprolinamides.

a, Superposition of the X-ray crystal structure of ribosome-bound lincosamide antibiotic clindamycin (2, blue, PDB entry 4V7V30) with the energy-minimized structure of OPP-1 (green). Note that in this configuration, the C7′-atom of OPP-1 contacts the lipophilic surface of the A-site cleft. b, The same structure, overlaid with the X-ray crystal structure of iboxamycin (IBX, yellow) bound to the bacterial ribosome.

Extended Data Fig. 2 MICs (μg ml−1) of antibiotics containing a bicyclic aminoacyl residue.

a, Effects of of 7′ substitution, ring size, and saturation on antibacterial activity. b, Effects of 7′-alkyl substituent chain length on antibacterial activity, including against MLSB-resistant S. aureus and strains of E. coli engineered to lack key efflux or outer-membrane assembly machinery. c-ermA/B, constitutively expressed erythromycin ribosome methylase A/B gene.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Effects of iboxamycin on mammalian cells.

a, Normalized hemolysis (mean ± s.d.) of human erythrocytes by IBX (n = 3 replicates) and clindamycin (n = 5 replicates) relative to Triton X-100 (n = 45 replicates) measured over one independent experiment. b, c, Mitochondrial ToxGlo data showing effects of IBX on HepG2 cellular membrane integrity and ATP production relative to vehicle-treated control (antimycin serves as a positive control for mitotoxicity). Data are mean ± s.d.; n = 3 technical replicates from one independent experiment. d–f, Comparison of effects of IBX, clindamycin, doxycycline, and azithromycin on cell viability (CellTiter-Blue). Data are the mean ± s.d. of n = 3 independent experiments performed in technical quintuplicate. Where applicable, GI50 values (µM) are reported beside the dose-response curves.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Efficacy of iboxamycin (IBX) in mouse models of infection. Bacterial counts were quantified in the thighs of neutropenic mice infected with S. pyogenes ATCC 19615.

(a), S. aureus MRSA HAV017 (b), A. baumannii ATCC 19616 (c) or E. coli MDR HAV504 (d) treated with IBX, vehicle, or comparator antibiotic at the listed time points post-treatment. Data are mean ± s.d.; n = 8 thighs from 4 mice examined over 2 experiments, with the exception the sub-set of part c where mice received IBX via intravenous administration (n = 4 thighs from 2 mice examined over a single experiment). e, Mouse survival in an an S. pyogenes systemic infection model. Abbreviations: AZM, azithromycin; CLI, clindamycin; CPFX, ciprofloxacin; IP, intraperitoneal administration; IV, intravenous administration..

Extended Data Fig. 6 Iboxamycin (IBX) efficiently arrests translation at the start codon.

Toeprinting analysis showing sites of IBX-induced translation arrest of ErmBL and ErmDL leader peptides. Because all reactions contained mupirocin, an inhibitor of Ile-tRNA synthetase, the ribosomes that escape inhibition by ribosome-targeting antibiotics are trapped at the codon preceding Ile (black arrowheads). Red arrowheads mark translation arrest at the start codon, while cyan arrowheads denote known erythromycin-induced arrest sites D10 (ermBL) and L7 (ermDL). Each gel is representative of two independent experiments, for source data see Supplementary Figure 1. ERY, erythromycin; CLI, clindamycin.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Time-kill kinetics, post-antibiotic effect, and post-antibiotic sub-MIC effect data of iboxamycin (IBX) against susceptible strains.

a, Arrayed growth curves for three susceptible strains showing concentration effects on growth inhibition (time-kill), growth kinetics following exposure to antibiotic at 4×MIC (PAE), and growth kinetics under sub-MIC concentrations following exposure to antibiotic at 4×MIC (PA-SME). Points represent mean values from n = 2 biologically independent experiments. b, Tabulated PAE and PA-SME durations (determined as the difference in time required for bacterial counts to rise 10× between experimental and untreated control arms). Abbreviations: CLI, clindamycin; LNZ, linezolid.

Extended Data Fig. 7 High-resolution electron density maps of iboxamycin (IBX) bound to the bacterial ribosome.

a, b, Unbiased Fo-Fc and 2Fo-Fc electron density maps of IBX in complex with the T. thermophilus 70S ribosome (green and blue mesh, respectively). The refined model of IBX is displayed in its electron density before (a) and after (b) the refinement contoured at 3.0σ and 1.5σ, respectively c, Superposition of ribosome-bound IBX (yellow) with prior structures of clindamycin bound to the tRNA-free 70S ribosome from eubacterium E. coli (blue, PDB entry 4V7V30) or to the 50S ribosomal subunit from archaeon H. marismortui harboring the 23S rRNA mutation G2099A (green, PDB entry 1YJN48). All structures were aligned based on domain V of the 23S rRNA. d, 2Fo-Fc electron density map (blue mesh) corresponding to ribosome-bound IBX (yellow), deacylated A-site tRNAPhe (green) and aminoacylated initiator P-site fMet-NH-tRNAiMet (dark blue). The refined models of tRNAs are displayed in their respective electron-density maps contoured at 1.0σ. In d, the entire bodies of the A- and P-site tRNAs are viewed from the back of the 50S subunit, as indicated by the inset. Ribosome subunits are omitted for clarity. Note that IBX binding to the ribosome prevents accommodation of the aminoacyl-bearing CCA-end of the A-site tRNA. e, Close-up view of the P-site tRNA CCA-end bearing a formyl-methionyl (cyan) residue. f, Detailed arrangement of the hydrogen bonds formed between the aminooctose component of IBX with 23S rRNA residues A2058 and G2505 (light blue).

Supplementary information

Supplementary Figure 1

Uncropped mRNA toeprinting gel image.

Supplementary Methods

| .docx file | Antimicrobial susceptibility assays; susceptibility testing of a spontaneously resistant mutant; consideration of predictive rules for Gram-negative accumulation; structural basis for Cfr-mediated resistance to lincosamides; chemical synthesis of oxepanoprolinamide analogs.

Supplementary Table 1

In vitro antibacterial activity of iboxamycin.

Supplementary Table 2

X-ray crystallographic data for iboxamycin–ribosome complexes.

Supplementary Video

Illustration of iboxamycin binding to the wild-type ribosome, and iboxamycin-induced displacement of \({\text{m}}_{2}^{6}\text{A}2058\) in the Erm-modified ribosome.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mitcheltree, M.J., Pisipati, A., Syroegin, E.A. et al. A synthetic antibiotic class overcoming bacterial multidrug resistance. Nature 599, 507–512 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-04045-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-04045-6

This article is cited by

-

Breaking resistance: strategies for novel antibacterial therapeutic interventions

Molecular Biology Reports (2026)

-

Copper Single-Atoms Loaded on Molybdenum Disulphide Drive Bacterial Cuproptosis-Like Death and Interrupt Drug-Resistance Compensation Pathways

Nano-Micro Letters (2026)

-

Discovery of a fluorinated macrobicyclic antibiotic through chemical synthesis

Nature Chemistry (2025)

-

Poly(imidazolium ester) antibiotic forms intracellular polymer-nucleic acid biomolecular condensates and fight drug-resistant bacteria

Nature Communications (2025)

-

A broad-spectrum lasso peptide antibiotic targeting the bacterial ribosome

Nature (2025)