Abstract

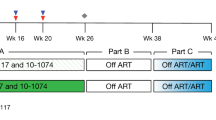

Antiretroviral therapy is highly effective in suppressing human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)1. However, eradication of the virus in individuals with HIV has not been possible to date2. Given that HIV suppression requires life-long antiretroviral therapy, predominantly on a daily basis, there is a need to develop clinically effective alternatives that use long-acting antiviral agents to inhibit viral replication3. Here we report the results of a two-component clinical trial involving the passive transfer of two HIV-specific broadly neutralizing monoclonal antibodies, 3BNC117 and 10-1074. The first component was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial that enrolled participants who initiated antiretroviral therapy during the acute/early phase of HIV infection. The second component was an open-label single-arm trial that enrolled individuals with viraemic control who were naive to antiretroviral therapy. Up to 8 infusions of 3BNC117 and 10-1074, administered over a period of 24 weeks, were well tolerated without any serious adverse events related to the infusions. Compared with the placebo, the combination broadly neutralizing monoclonal antibodies maintained complete suppression of plasma viraemia (for up to 43 weeks) after analytical treatment interruption, provided that no antibody-resistant HIV was detected at the baseline in the study participants. Similarly, potent HIV suppression was seen in the antiretroviral-therapy-naive study participants with viraemia carrying sensitive virus at the baseline. Our data demonstrate that combination therapy with broadly neutralizing monoclonal antibodies can provide long-term virological suppression without antiretroviral therapy in individuals with HIV, and our experience offers guidance for future clinical trials involving next-generation antibodies with long half-lives.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

TCR sequencing data are available online (https://clients.adaptivebiotech.com/login; login: chun-review@adaptivebiotech.com, password: chun2021review). The HIV-specific CDR3 sequences were downloaded from the following four databases: the immune epitope database (IEDB; http://www.iedb.org/), VDJdb (https://vdjdb.cdr3.net), McPAS-TCR (http://friedmanlab.weizmann.ac.il/McPAS-TCR/) and the Pan Immune Repertoire Database (PIRD; https://db.cngb.org/pird/).

Code availability

The R scripts that were used in the data analysis have been deposited at GitHub (https://github.com/cihangenome/combination-antibodies-HIV). The following R packages were used: factoextra (v.1.0.7), FactoMineR (v.2.4), reshape (v.0.8.8), reshape2 (v.1.4.4), writexl (v.1.4.0), gdata (v.2.18.0), psych (v.2.1.9), car (v.3.0-11), carData (v.3.0-4), corrr (v.0.4.3), lubridate (v.1.8.0), readxl (v.1.3.1), forcats (v.0.5.1), stringr (v.1.4.0), purrr (v.0.3.4), readr (v.2.0.2), tidyr (v.1.1.4), tibble (v.3.1.5), tidyverse (v.1.3.1), ggpubr (v.0.4.0), immunarch (v.0.6.6), patchwork (v.1.1.1), data.table (v.1.14.2), dtplyr (v.1.1.0), dplyr (v.1.0.7) and ggplot2 (v.3.3.5).

References

Deeks, S. G., Lewin, S. R. & Havlir, D. V. The end of AIDS: HIV infection as a chronic disease. Lancet 382, 1525–1533 (2013).

Chun, T. W., Moir, S. & Fauci, A. S. HIV reservoirs as obstacles and opportunities for an HIV cure. Nat. Immunol. 16, 584–589 (2015).

Chun, T. W., Eisinger, R. W. & Fauci, A. S. Durable control of HIV infection in the absence of antiretroviral therapy: opportunities and obstacles. JAMA 322, 27–28 (2019).

Ndung’u, T., McCune, J. M. & Deeks, S. G. Why and where an HIV cure is needed and how it might be achieved. Nature 576, 397–405 (2019).

Cohn, L. B., Chomont, N. & Deeks, S. G. The biology of the HIV-1 latent reservoir and implications for cure strategies. Cell Host Microbe 27, 519–530 (2020).

Sengupta, S. & Siliciano, R. F. Targeting the latent reservoir for HIV-1. Immunity 48, 872–895 (2018).

Chun, T. W. et al. Presence of an inducible HIV-1 latent reservoir during highly active antiretroviral therapy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 94, 13193–13197 (1997).

Finzi, D. et al. Identification of a reservoir for HIV-1 in patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy. Science 278, 1295–1300 (1997).

Wong, J. K. et al. Recovery of replication-competent HIV despite prolonged suppression of plasma viremia. Science 278, 1291–1295 (1997).

Margolis, D. M. et al. Curing HIV: seeking to target and clear persistent infection. Cell 181, 189–206 (2020).

Lewin, S. R. & Rasmussen, T. A. Kick and kill for HIV latency. Lancet 395, 844–846 (2020).

Swindells, S. et al. Long-acting cabotegravir and rilpivirine for maintenance of HIV-1 suppression. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, 1112–1123 (2020).

Orkin, C. et al. Long-acting cabotegravir and rilpivirine after oral induction for HIV-1 infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, 1124–1135 (2020).

Overton, E. T. et al. Long-acting cabotegravir and rilpivirine dosed every 2 months in adults with HIV-1 infection (ATLAS-2M), 48-week results: a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 3b, non-inferiority study. Lancet 396, 1994–2005 (2021).

Caskey, M., Klein, F. & Nussenzweig, M. C. Broadly neutralizing anti-HIV-1 monoclonal antibodies in the clinic. Nat. Med. 25, 547–553 (2019).

Haynes, B. F., Burton, D. R. & Mascola, J. R. Multiple roles for HIV broadly neutralizing antibodies. Sci. Transl. Med. 11, eaaz2686 (2019).

Gama, L. & Koup, R. A. New-generation high-potency and designer antibodies: role in HIV-1 treatment. Annu. Rev. Med. 69, 409–419 (2018).

Nishimura, Y. & Martin, M. A. Of mice, macaques, and men: broadly neutralizing antibody immunotherapy for HIV-1. Cell Host Microbe 22, 207–216 (2017).

Bar, K. J. et al. Effect of HIV antibody VRC01 on viral rebound after treatment interruption. N. Engl. J. Med. 375, 2037–2050 (2016).

Caskey, M. et al. Viraemia suppressed in HIV-1-infected humans by broadly neutralizing antibody 3BNC117. Nature 522, 487–491 (2015).

Caskey, M. et al. Antibody 10-1074 suppresses viremia in HIV-1-infected individuals. Nat. Med. 23, 185–191 (2017).

Scheid, J. F. et al. HIV-1 antibody 3BNC117 suppresses viral rebound in humans during treatment interruption. Nature 535, 556–560 (2016).

Mendoza, P. et al. Combination therapy with anti-HIV-1 antibodies maintains viral suppression. Nature 561, 479–484 (2018).

Nishimura, Y. et al. Early antibody therapy can induce long-lasting immunity to SHIV. Nature 543, 559–563 (2017).

Lu, C. L. et al. Enhanced clearance of HIV-1-infected cells by broadly neutralizing antibodies against HIV-1 in vivo. Science 352, 1001–1004 (2016).

Schoofs, T. et al. HIV-1 therapy with monoclonal antibody 3BNC117 elicits host immune responses against HIV-1. Science 352, 997–1001 (2016).

Niessl, J. et al. Combination anti-HIV-1 antibody therapy is associated with increased virus-specific T cell immunity. Nat. Med. 26, 222–227 (2020).

Sneller, M. C. et al. A randomized controlled safety/efficacy trial of therapeutic vaccination in HIV-infected individuals who initiated antiretroviral therapy early in infection. Sci. Transl. Med. 9, eaan8848 (2017).

Deeks, S. G. HIV infection, inflammation, immunosenescence, and aging. Annu. Rev. Med. 62, 141–155 (2011).

Van Gassen, S. et al. FlowSOM: using self-organizing maps for visualization and interpretation of cytometry data. Cytometry A 87, 636–645 (2015).

Nishimura, Y. et al. Immunotherapy during the acute SHIV infection of macaques confers long-term suppression of viremia. J. Exp. Med. 218, e20201214 (2021).

Barouch, D. H. & Deeks, S. G. Immunologic strategies for HIV-1 remission and eradication. Science 345, 169–174 (2014).

Collins, D. R., Gaiha, G. D. & Walker, B. D. CD8+ T cells in HIV control, cure and prevention. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 20, 471–482 (2020).

Kwong, P. D. & Mascola, J. R. HIV-1 vaccines based on antibody identification, B cell ontogeny, and epitope structure. Immunity 48, 855–871 (2018).

Sok, D. & Burton, D. R. Recent progress in broadly neutralizing antibodies to HIV. Nat. Immunol. 19, 1179–1188 (2018).

Collins, D. R. et al. Functional impairment of HIV-specific CD8+ T cells precedes aborted spontaneous control of viremia. Immunity 54, 2372–2384 (2021).

Migueles, S. A. & Connors, M. Success and failure of the cellular immune response against HIV-1. Nat. Immunol. 16, 563–570 (2015).

Sarzotti-Kelsoe, M. et al. Optimization and validation of the TZM-bl assay for standardized assessments of neutralizing antibodies against HIV-1. J. Immunol. Methods 409, 131–146 (2014).

Clarridge, K. E. et al. Effect of analytical treatment interruption and reinitiation of antiretroviral therapy on HIV reservoirs and immunologic parameters in infected individuals. PLoS Pathog. 14, e1006792 (2018).

Bruner, K. M. et al. A quantitative approach for measuring the reservoir of latent HIV-1 proviruses. Nature 566, 120–125 (2019).

Myers, L. E., McQuay, L. J. & Hollinger, F. B. Dilution assay statistics. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32, 732–739 (1994).

Robins, H. S. et al. Comprehensive assessment of T-cell receptor β-chain diversity in αβ T cells. Blood 114, 4099–4107 (2009).

Carlson, C. S. et al. Using synthetic templates to design an unbiased multiplex PCR assay. Nat. Commun. 4, 2680 (2013).

Snyder, T. M. et al. Magnitude and dynamics of the T-cell response to SARS-CoV-2 infection at both individual and population levels. Preprint at MedRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.31.20165647 (2020).

ImmunoMind Team. immunarch: an R package for painless bioinformatics analysis of T-cell and B-cell immune repertoires (version 0.6.7) (Zenodo, 2019).

Vita, R. et al. The immune epitope database (IEDB): 2018 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D339–D343 (2019).

Shugay, M. et al. VDJdb: a curated database of T-cell receptor sequences with known antigen specificity. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, D419–D427 (2018).

Tickotsky, N., Sagiv, T., Prilusky, J., Shifrut, E. & Friedman, N. McPAS-TCR: a manually curated catalogue of pathology-associated T cell receptor sequences. Bioinformatics 33, 2924–2929 (2017).

Zhang, W. et al. PIRD: pan immune repertoire database. Bioinformatics 36, 897–903 (2020).

Kassambara, A. ggpubr: ‘ggplot2’ based publication ready plots. R package version 0.1.7 (2018).

Lê, S., Josse, J. & Husson, F. FactoMineR: an R package for multivariate analysis. J. Stat. Softw. 25, 1–18 (2008).

Acknowledgements

We thank the study volunteers for their participation in this study; D. Asmuth, J. Mascola and S. Read for their guidance; and the NIAID HIV Outpatient Clinic staff for their assistance in the execution of this study. This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.C.S. and T.-W.C. designed the clinical trial and research. J.B., J.S.J., V.S., B.D.K., E.J.W., R.F.S. M.S.S., S.M. and T.-W.C. performed experiments. J.B. and C.O. performed bioinformatic analysis. M.C.S., K.G., J.T., G.M., E.B., C.K. and T.-W.C. contributed to recruitment of study participants. M.C. and M.C.N. provided study drugs. M.C.S., J.B., M.A.P., C.O., M.S.S, S.M. and T.-W.C. analysed data. M.C.S., A.S.F., S.M. and T.-W.C. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

M.C.N. is listed as an inventor for patents on 3BNC117 (PTC/US2012/038400) and 10-1074 (PTC/US2013/065696); 3BNC117 and 10-1074 are licensed to Gilead Sciences by Rockefeller University from which M.C.N. has received payments. M.C.N. is a member of the Scientific Advisory Boards of Celldex Therapeutics, Walking Fish Therapeutics and Frontier Biotechnologies. M.C.N. had no control over the direction and ultimately the reporting of the clinical portion of the research while holding their financial interests. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature thanks Lu Zheng and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

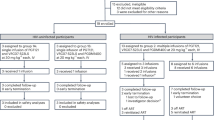

Extended Data Fig. 1 Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram for the trial.

CONSORT diagram shows the study enrolment of 14 participants who underwent randomization to the bNAb or placebo groups.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Dynamics of HIV reservoirs.

a. Frequencies of CD4+ T cells carrying total HIV DNA in study participants in the placebo arm of Group 1. b. Frequencies of CD4+ T cells carrying total HIV DNA in study participants in the Group 2 in whom plasma viraemia was suppressed by the combination bNAbs.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Longitudinal measurements of CD4+ T cell counts and phenotypic analyses of CD8+ T cells.

a. Levels of CD4+ T cell counts of the bNAb (n = 7) and placebo (n = 7) arms of Group 1 and Group 2 (n = 5) study participants are shown. b. Frequencies of the activation/exhaustion markers TIGIT, PD-1, CD38 and HLA-DR (left) and T cell subsets (TN, naive; TCM, central memory; TTM, transitional memory; TEM, effector memory; TTD, terminally differentiated) on CD8+ T cells of the bNAb (n = 5) and placebo (n = 7) arms of Group 1 and Group 2 (n = 5) study participants are shown. The grey lines indicate median values. P values were determined using the two-sided Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test and were adjusted for multiple testing. ns, not significant.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Phenotypic analysis of T cells.

Longitudinal high-dimensional flow cytometric analyses of PBMCs of study participants. a. Global opt-SNE plots of CD3+ T cells of combined data from each group of study participants. b. Opt-SNE visualization of expression of the indicated markers are shown. c. Opt-SNE map of T cell clusters identified by FlowSOM clustering. Each number indicates a distinct cluster. Heatmap shows the level of expression (MFI) within individual clusters. d. Comparison of frequencies of T cells expressing markers associated with indicated clusters in the bNAb (n = 5) and placebo (n = 7) arms of Group 1 and Group 2 (n = 5) study participants are shown. P values were determined using the two-sided Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test and were adjusted for multiple testing. ns, not significant.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Levels of biomarkers in the plasma of the bNAb (n = 5) and placebo (n = 7) arms of Group 1 and Group 2 (n = 5) study participants over time.

The grey lines indicate median values. P values were determined using the two-sided Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test and were adjusted for multiple testing. ns, not significant.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Analysis of HIV-specific CD8+ T cells.

Frequencies of HIV Gag-specific CD8+ T cells and dynamics of CD8+ T cell receptor (TCR) repertoire. a. Frequencies of polyfunctional (IFN-γ+TNF-α+MIP-1β+) HIV Gag-specific CD8+ T cells in the bNAb (n = 5) and placebo (n = 7) arms of Group 1 and Group 2 (n = 5) study participants are shown. The grey lines indicate median values. P values were determined using the two-sided Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test. b. Changes in the HIV-specific breadth and depth of CD8+ T cells of study participants are shown (upper panels). Highly enriched CD8+ T cells were obtained using a bead-based purification method. The analysis includes 35 CD8+ T cell-derived genomic DNA samples from 12 study participants (15 samples from 5 participants in the bNAb arm of Group 1, 5 samples from 2 participants in the placebo arm of Group 1, and 15 samples from 5 participants in Group 2). Violin plots show the Gaussian kernel probability density of the breadth/depth values over time. The median values and interquartile ranges of the time point-specific distribution are shown as circles and vertical lines, respectively. Principal component analysis (PCA) of the changes in the TCR repertoire characteristics is shown (lower panels). Each ellipse shows the 95% confidence interval in the PCA space and the center of each ellipse is indicated by larger sized symbols that represent specific time points. Lower left panels depict PCA results with the frequencies of the HIV-specific clonotypes ranked among the top 25 with respect to their P values associated with the pairwise comparisons between the three time points. Lower right panels depict PCA results with the gene usage profiles derived from the TRBV-TRBJ gene pairs in the above clonotypes. Principal component (PC) 1 and PC2 represent a lower-dimensional representation of the input data consisting of the frequencies of the HIV-specific clonotypes (lower left panel) and the usage levels of the TRBV-TRBJ gene pairs (lower right panel) for each patient group. P values were determined using the two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Tables 1–5 and Supplementary Fig.1, containing the gating strategy for flow cytometry analysis.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sneller, M.C., Blazkova, J., Justement, J.S. et al. Combination anti-HIV antibodies provide sustained virological suppression. Nature 606, 375–381 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04797-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04797-9

This article is cited by

-

A Nonparametric Approach to Practical Identifiability of Nonlinear Mixed Effects Models

Bulletin of Mathematical Biology (2026)

-

Clinical trials of broadly neutralizing monoclonal antibodies in people living with HIV – a review

AIDS Research and Therapy (2025)

-

Immune-mediated strategies to solving the HIV reservoir problem

Nature Reviews Immunology (2025)

-

Minor SHIV variants abrogate protective efficacy of broadly neutralizing antibodies in rhesus macaques

Nature Communications (2025)

-

CD8+ T cell stemness precedes post-intervention control of HIV viraemia

Nature (2025)